Abstract

A recent paper by Rasmussen et al., (New Phytol 2007; 173:787–97) describes the interactions between Lolium perenne cultivars with contrasting carbohydrate content and the symbiotic fungal endophyte Neotyphodium lolii at different levels of nitrogen supply. In a subsequent study undertaken by Rasmussen et al., (Plant Physiol 2008; 146:1440–53) 66 metabolic variables were analysed in the same material, revealing widespread effects of endophyte infection, N supply and cultivar carbohydrate content on both primary and secondary metabolites. Here, we link insect numerical responses to these metabolic responses using multiple regression analysis.

Key words: Neotyphodium lolii, Lolium perenne, high sugar grasses, metabolomics, insect herbivores

Pasture grasses are often infected with symbiotic fungal endophytes and benefits for host plants arising out of these associations are generally ascribed to endophyte produced anti-herbivorous alkaloids. We tested the effects of (i) infection with three strains of endophytes differing in their alkaloid profiles, (ii) high vs. low nitrogen (N) supply, and (iii) ryegrass cultivars with high vs. control levels of water soluble carbohydrates (WSCs) on numerical insect responses (aphids, thrips, mites). A difference in WSC content between the cultivars had no significant effect on insect numbers, whereas high N compared to low N supply increased mites, thrips and alate Rhopalosiphum spp., but decreased apterous Rhopalosiphum spp. The effect of endophyte infection was strain dependant and differed for the different insects.

A total of 66 metabolic variables of the same plants analysed prior to insect treatment were linked to insect responses using multiple regression analysis. One of the major conclusions to be drawn is that alkaloids are not always the most important factor influencing numerical insect responses which will also be determined by other metabolites, clearly indicating the importance of metabolomics type studies to point the way toward a mechanistic explanation of grass-endophyte-herbivore interactions.

Grass species are often hosts of symbiotic clavicipitaceous endophytic fungi1 residing in the apoplastic spaces of above ground plant parts and usually not causing any visible symptoms of infection.2–4 These fungal symbionts confer protection from insect herbivory to their host plants through alkaloids,5–8 some of which (ergovaline, lolitrem B) are also toxic to grazing mammals.9,10 Natural endophyte strains lacking these mammalian toxins, but still retaining at least some of their insect deterring features, have been commercialized and are now widely used in ryegrass and tall fescue based pastures.11,12

Insights into Molecular Grass-Endophyte Interactions

In a previous study13,14 we infected two ryegrass cultivars differing in their water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) content with three N. lolii strains (common strain CS—produces peramine, lolitrem B and ergovaline; AR1—produces peramine only; AR37—produces janthitrems only), and grew them at two nitrogen (N) levels. We quantified endophyte concentrations and 66 metabolic variables in the symbiotic tissue. Major findings were: Both, high N supply and high WSC content reduced fungal endophyte and alkaloid concentrations by approx. half, resulting in a 75% reduction in the high sugar cultivar at high N. A principal component analysis with subsequent factor rotation of the metabolic variables showed that (i) at high N proteins, major amino acids, organic acids and lipids were increased; WSCs, chlorogenic acid and fibers were decreased; (ii) the high sugar cultivar AberDove had reduced levels of nitrate, most minor amino acids, sulfur and fibers, whereas WSCs, CGA, and methionine were increased; (iii) plants infected with endophytes had increased levels of WSCs, some organic acids, lipids and CGA, whereas nitrate and several amino acids, esp., L-asparagine, were decreased.

Several of these metabolites have been linked to plant quality for various herbivores.15–20 We were interested in whether such changes in plant quality could be linked directly to herbivore performance (rather than indirectly via a treatment effect).

Insect Herbivore Performance and Plant Metabolic Quality

After harvesting the blades, plants were enclosed in plastic boxes and two alate adults of Rhopalosiphum padi L. were added to each plant. In addition to these aphids, two other aphid species, Sitobion nr frageriae and Aploneura lentisci, a variety of thrip (Frankliniella occidentalis) and an unidentified mite species were already present on the plants prior to enclosure. We also found some R. insertum aphids on the plants, but analysed those together with R. padi numbers.

After four weeks, we recorded the number of individual Rhopalosiphum spp., (apterous, alate), S. nr frageriae (apterous) and A. lentisci aphids. Alate S. nr frageriae were absent from most plants and were not included in the statistical analysis. We did not differentiate between Rhopalosiphum and Sitobion nymphs and, due to the fact that the adult aphid species responded differently to the treatments, we did not include total nymphs in our statistical analysis but report the numbers. Only young nymphs of A. lentisci were found on the foliage. This species lives primarily on roots of grasses which were not sampled for aphids, so we also excluded A. lentisci found on the foliage from our statistical analysis. For the majority of these response variables, both N supply and endophyte status significantly altered herbivore numbers (Figs. 1 and 2); however, differences in the WSC content of the two cultivars did not have any significant effect on insect responses.

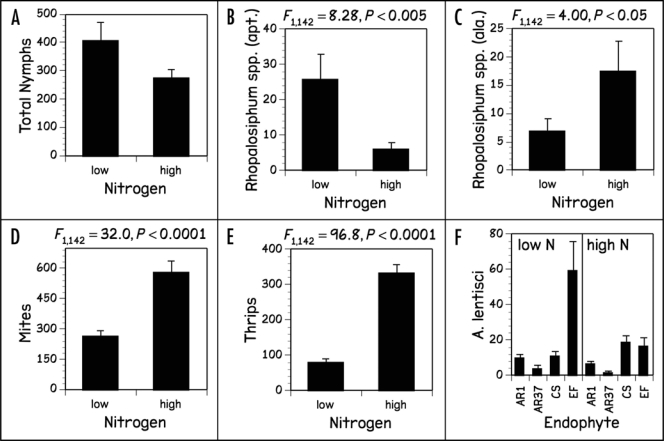

Figure 1.

Numbers of (A) total nymphs, (B) apterous, (C) alate Rhopalosiphum spp., (D) mites, (E) thrips and (F) A. lentisci nymphs found on foliage of L. perenne plants grown at low and high N supply.

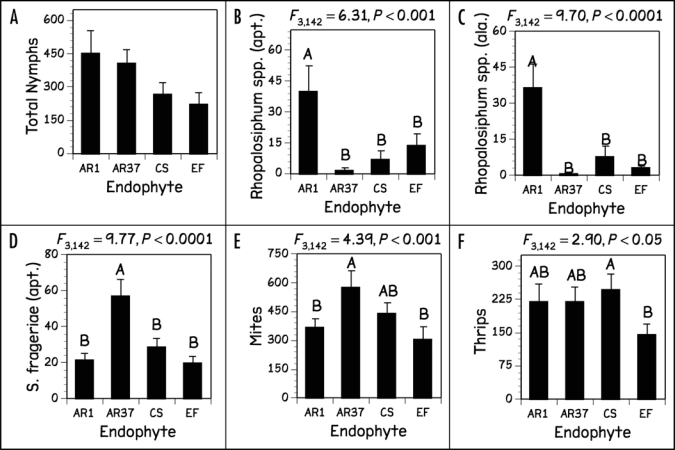

Figure 2.

Numbers of (A) total nymphs, (B) apterous, (C) alate Rhopalosiphum spp., (D) apterous S. frageriae, (E) mites and (F) thrips on foliage of L. perenne plants infected with different endophyte strains or uninfected (different letters denote means that are significantly different as determined by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test).

To link insect responses to metabolite profiles we used multiple regression analysis and Akaike's Information Criterion to select the best model of herbivore numerical responses from among the measured metabolites. After finding the best fitting models, we standardized all the response and predicting variables, so that they each had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. We then re-fitted the best regression models. This method means that the magnitude of the slopes can be directly compared across metabolites, despite their very different concentrations. These regression equations are shown below.

Conclusion and Outlook

Arguably, these results do not present a clear response of insect herbivores to endophytes and endophyte related alkaloid production, but Figures 1 and 2 and equations (1–5) permit several interesting observations. First, different groups of herbivores respond differently to the different endophyte strains: Rhopalosiphum spp., responded positively to AR1, and S. nr frageriae and mites positively to AR37. Second, different herbivores responded differently to specific alkaloids, e.g., Rhopalosiphum spp., responded positively to peramine, but negatively to lolitrem B. In contrast, S. nr frageriae responded negatively to peramine. Third, for responses of thrips and mites, alkaloids seemed to be unimportant. Although these results cannot be interpreted to mean there are direct positive or negative effects of these alkaloids they clearly show that population sizes of all herbivores are predicted by concentrations of metabolites other than alkaloids. Since we know that a large range of metabolites varies with endophyte infection, strain and concentration, the overriding conclusion from these results is that alkaloids are certainly not the only factors, and may not even be the most important factor in the endophyte-grass-herbivore story. Furthermore, we also know that in addition to the known alkaloids, there are a range of other endophyte specific metabolites that have just recently been discovered and which may have biological activity as well,21 but were not part of our analysis. A note of caution should be added here as well, as we have not included possible insect species interactions into our analysis. Thus, where populations of an insect species, particularly an opportunistic one, are reduced by an endophyte, that niche may be filled opportunistically by another species that is not negatively affected by that endophyte.

An additional complicating issue for our analysis is certainly that aphids are phloem feeders, and that the degree to which metabolite and alkaloid concentrations in whole blade extracts covary with those in phloem sap is, as yet, unknown.17,22,23 There is clearly much more work to be done to fully understand this interaction, and a combination of transcriptomics and metabolomics approaches in an ecological context seems likely to eventually point the way toward a mechanistic explanation of these interactions.24–27 This type of study might also help reconcile conflicting evidence found in the literature regarding the overall nature of the grass-Neotyphodium symbiosis,28–30 and especially to unravel the mechanisms underlying the dynamics of the mutualism-parasitism continuum of this association.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marlon Stufkens and Mette Nielson (Crop and Food Research, NZ) for identification of aphids and thrips.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/6171

References

- 1.Leuchtmann A. Systematics, distribution, and host specificity of grass endophytes. Nat Toxins. 1993;1:150–162. doi: 10.1002/nt.2620010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clay K. Fungal endophytes of grasses. Ann Rev Ecol System. 1990;21:275–297. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clay K, Schardl C. Evolutionary origins and ecological consequences of endophyte symbiosis with grasses. Am Nat. 2002;160:99–127. doi: 10.1086/342161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen MJ, Bennett RJ, Ansari HA, Koga H, Johnson RD, Bryan GT, Simpson WR, Koolaard JP, Nickless EM, Voisey CR. Epichloë endophytes grow by intercalary hyphal extension in elongating grasses. Fungal Gent Biol. 2008;45:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel MR, Latch GCM, Bush LP, Fannin FF, Rowan DD, Tapper BA, Bacon CW, Johnson MC. Fungal endophyte-infected grasses: Alkaloid accumulation and aphid response. J Chem Ecol. 1990;16:3301–3315. doi: 10.1007/BF00982100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowan DD, Latch GCM. Utilization of endophyte-infected perennial ryegrasses for increased insect resistance. In: Bacon CW, White JF Jr, editors. Biotechnology of endophytic fungi of grasses. Vol. 12. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush LP, Wilkinson HH, Schardl CL. Bioprotective alkaloids of grass-fungal endophyte symbioses. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schardl CL, Grossman RB, Nagabhyru P, Faulkner JR, Mallik UP. Loline alkaloids: Currencies of mutualism. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:980–996. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher RT, Hawkes AD, Steyn PS, Vleggaar R. Tremorgenic neurotoxins from perennial ryegrass causing ryegrass staggers disorder of livestock—Structure elucidation of Lolitrem-B. J Chem Soc—Chem Comm. 1984:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons PC, Plattner RD, Bacon CW. Occurrence of peptide and clavine ergot alkaloids in tall fescue grass. Science. 1986;232:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.3008328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher LR, Easton HS. The evaluation of use of endophytes for pasture improvement. In: Bacon CW, Hill NS, editors. Neotyphodium/grass interactions. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt MG, Newman JA. Reduced herbivore resistance from a novel grass-endophyte association. J Appl Ecol. 2005;42:762–769. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen S, Parsons AJ, Bassett S, Christensen MJ, Hume DE, Johnson LJ, Johnson RD, Simpson WR, Stacke C, Voisey CR, Xue H, Newman JA. High nitrogen supply and carbohydrate content reduce fungal endophyte and alkaloid concentration in Lolium perenne. New Phytol. 2007;173:787–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen S, Parsons AJ, Fraser K, Xue H, Newman JA. Metabolic profiles of Lolium perenne are differentially affected by nitrogen supply, carbohydrate content, and fungal endophyte infection. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1440–1453. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown ASS, Simmonds MSJ, Blaney WM. Relationship between nutritional composition of plant species and infestation levels of thrips. J Chem Ecol. 2002;28:2399–2409. doi: 10.1023/a:1021471732625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman JA, Gibson DJ, Parsons AJ, Thornley JHM. How predictable are aphid population responses to elevated CO2? J Anim Ecol. 2003;72:556–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douglas AE. Phloem-sap feeding by animals: problems and solutions. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:747–754. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douglas AE, Price DRG, Minto LB, Jones E, Pescod KV, François CLMJ, Pritchard J, Boonham N. Sweet problems: insect traits defining the limits to dietary sugar utilisation by the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:1395–1403. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Opit GP, Jonas VM, Williams KA, Nechols JR, Margolies DC. Twospotted spider mite population level, distribution, and damage on ivy geranium in response to different nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization regimes. Hort Entom. 2007;100:1821–1830. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493(2007)100[1821:tsmpld]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krauss J, Harri SA, Bush L, Husi R, Bigler L, Power SA, Müller CB. Effects of fertilizer, fungal endophytes and plant cultivar on the performance of insect herbivores and their natural enemies. Funct Ecol. 2007;21:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao M, Koulman A, Johnson LJ, Lane GA, Rasmussen S. Advanced data-mining strategies for the analysis of direct-infusion ion trap mass spectrometry data from the association of perennial ryegrass with its endophytic fungus, Neotyphodium lolii. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1–14. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auclair JL. Aphid feeding and nutrition. Annu Rev Entomol. 1963;8:439–490. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koulman A, Lane GA, Christensen MJ, Tapper BA. Peramine and other fungal alkaloids are exuded in the guttation fluid of endophyte-infected grasses. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldwin IT, Halitschke R, Kessler A, Schittko U. Merging molecular and ecological approaches in plant-insect interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goggin FL. Plant-aphid interactions: molecular and ecological perspectives. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walling LL. Avoiding effective defenses: Strategies employed by phloem-feeding insects. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:859–866. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng SJ, Dicke M. Ecological genomics of plant-insect interactions: From gene to community. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:812–817. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faeth SH, Sullivan TJ. Mutualistic asexual endophytes in a native grass are usually parasitic. Am Nat. 2003;161:310–325. doi: 10.1086/345937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheplick GP. Costs of fungal endophyte infection in Lolium perenne genotypes from Eurasia and North Africa under extreme resource limitation. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;60:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saikkonen K, Lehtonen P, Helander M, Koricheva J, Faeth SH. Model systems in ecology: dissecting the endophyte-grass literature. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;11:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]