Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in response to many environmental stresses, such as UV, chilling, salt and pathogen attack. These stresses also accompany leaf abscission in some plants, however, the relationship between these stresses and abscission is poorly understood. In our recent report, we developed an in vitro abscission system that reproduces stress-induced pepper leaf abscission in planta. Using this system, we demonstrated that continuous production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is involved in leaf abscission signaling. Continuous H2O2 production is required to induce expression of the cell wall-degrading enzyme, cellulase and functions downstream of ethylene in abscission signaling. Furthermore, enhanced production of H2O2 occurs at the execution phase of abscission, suggesting that H2O2 also plays a role in the cell-wall degradation process. These data suggest that H2O2 has several roles in leaf abscission signaling. Here, we propose a model for these roles.

Key words: leaf abscission, reactive oxygen species, H2O2, in vitro, ethylene, auxin, pepper, NADPH oxidase

Introduction

Abscission is a common process among higher plants, resulting in the detachment of plant organs, including leaves, flowers, fruits and seeds.1,2 Leaf abscission occurs during senescence, and is induced by biotic and abiotic stresses.1,3–6 Abscission results from degradation of the cell wall substances surrounding cells in a separation layer. This separation layer forms within a broad region of cells commonly referred to as the abscission zone (AZ). Multiple cell wall-degrading enzymes (WDEs), such as cellulases, are activated to dissolve cell wall substances in the execution phase of abscission.7,8 This pattern of activation suggests that abscission signaling is integrated into the activation of WDEs and other cell wall-disrupting factors.

To date, auxin and ethylene have been recognized as important regulators of abscission signaling.1 The decrease in indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) synthesis in the leaves reduces the flux of IAA to the AZ. Depletion of IAA sensitizes the AZ to ethylene, resulting in the activation of WDEs. Promoter analysis has revealed that ethylene positively regulates the expression of WDEs, such as polygalacturonases and cellulases. However, it is unlikely that ethylene directly activates WDE gene expression because ethylene-responsive element(s) cannot be found in the promoter region.9,10 Therefore, it is thought that signal mediators must link ethylene with WDE genes in abscission signaling.

H2O2 in Leaf Abscission Signaling

To search for signaling molecules involved in stress-induced abscission, we have established an in vitro abscission system in pepper11 in which 1-mm thick petiole strips separated at the AZ within 4 days of abscission treatment. This separation occurred through cell wall degradation in an IAA depletion- and ethylene-dependent manner. Using this experimental system, AZ strips can be directly treated with pharmacological reagents, allowing easy screening of the signal mediators involved in stress-induced leaf abscission signaling. We showed that ROS inhibitors suppressed continuous H2O2 production, prevented expression of the cellulase gene, and consequently prevented abscission. Conversely, application of H2O2 enhanced cellulase expression and abscission, indicating that production of H2O2 is important to induce abscission. During in vitro abscission, increased expression of ethylene-responsive genes is unaffected by H2O2 or ROS inhibitors, implying that H2O2 acts downstream from ethylene in abscission signaling. After continuously produced H2O2 induced cellulase, H2O2 production dramatically increased at the AZ in the AZ-separating period. Because ROS cleave plant cell wall polysaccharides and loosen the cell wall in vitro and in planta,12–14 the enhanced H2O2 levels in the late period may be associated with the cell wall degradation process.

ROS Regulate Multiple Steps in Leaf Abscission Signaling

A variety of ROS, including H2O2, superoxide, singlet oxygen, and the hydroxyl radical, are generated during stresses such as UV, chilling, high light, salt and pathogen attack.15 Excessive ROS production disrupts cellular components, including lipids, proteins and nucleic acids. This leads to metabolic dysfunction, such as inhibition of secondary metabolite synthesis.16 While we have shown a clear relationship between H2O2 and leaf abscission, other studies support a link between other types of ROS and abscission. In Populus tremuloides, exposure to ozone increased leaf abscission.17 Moreover, Michaeli et al., reported that chilling-induced leaf abscission in Ixora coccinea plants was enhanced by exposure to high light intensity.6 They hypothesized that ROS production in the leaves triggered by high light might lead to a reduction in IAA content, resulting in leaf abscission. Because oxidative stresses frequently cause excessive production of ROS in leaf cells, suppression of IAA synthesis by excessive ROS and subsequent activation of abscission signaling may be a general mechanism in stress-induced leaf abscission.

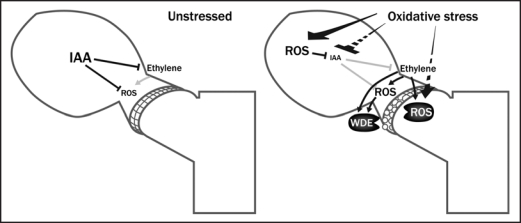

The mechanism of enhanced H2O2 production at the late stage of abscission probably differs from that in continuous H2O2 production, which is involved in abscission signaling. Our pharmacological study showed that NADPH oxidase is responsible for the latter.11 Recent molecular studies showed that peroxidases are commonly expressed during different types of abscission.18,19 Peroxidases are known to participate in the plant cell wall loosening process.13,20 Moreover, biotic and abiotic stresses induce expression of peroxidases and production of H2O2 at the cell wall.21–23 Thus, the massive production of ROS at the late stage of abscission is probably driven by these peroxidases. Figure 1 shows a possible model for the roles of ROS in stress-induced leaf abscission signaling. To date, only ROS and G-proteins have been shown to be involved in leaf abscission signaling beside auxin and ethylene.2,11,24 Our in vitro abscission system may help to clarify the ROS network and other new regulators in leaf abscission signaling.

Figure 1.

A proposed model for roles of ROS in stress-induced leaf abscission signaling. Oxidative stress causes excessive production of ROS within leaf cells. These ROS disrupt metabolism and therefore suppress the synthesis of IAA. Some stresses may cause decreased IAA synthesis without affecting ROS production. When IAA flux to the AZ is inhibited, AZ cells respond to ethylene and induce expression of WDEs, which is at least partly dependent on ROS derived from NADPH oxidase. In the late stage of abscission, ROS production at the AZ is increased by ethylene and/or another pathway, which act as direct factors in cell wall digestion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kazue Obara for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by the Iwate Prefectural government and in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (18580047) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/6737

References

- 1.Taylor JE, Whitelaw CA. Signals in abscission. New Phytol. 2001;151:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis MW, Leslie ME, Liljegren SJ. Plant separation: 50 ways to leave your mother. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ketring DL, Melouk HA. Ethylene Production and Leaflet Abscission of Three Peanut Genotypes Infected with Cercospora arachidicola Hori. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:789–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao Z, Craker LF, Decoteau DR. Abscission in Coleus: light and phytohormone control. J Exp Bot. 1989;40:1273–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Cadenas A, Tadeo FR, Talon M, Primo-Millo E. Leaf abscission induced by ethylene in water-stressed intact seedlings of Cleopatra Mandarin required previous abscisic acid accumulation in roots. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:401–408. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaeli R, Philosoph-Hadas S, Riov J, Shahak Y, Ratner K, Meir S. Chilling-induced leaf abscission of Ixora coccinea plants. III. Enhancement by high light via increased oxidative processes. Physiol Plant. 2001;113:338–345. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1130306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleecker AB, Patterson SE. Last exit: senescence, abscission and meristem arrest in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1169–1179. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Carranza ZH, Lozoya-Gloria E, Roberts JA. Recent development in abscission: shedding light on the shedding process. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong SB, Sexton R, Tucker ML. Analysis of gene promoters for two tomato polygalacturonases expressed in abscission zone and the stigma. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:869–881. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker ML, Whitelaw CA, Lyssenko NN, Nath P. Functional analysis of regulatory elements in the gene promoter for an abscission-specific cellulase from bean and isolation, expression and binding affinity of three TGA-type basic leucine zipper transcription. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1487–1496. doi: 10.1104/pp.007971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakamoto M, Munemura I, Tomita R, Kobayashi K. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in leaf abscission signaling, revealed by analysis with an in vitro abscission system in Capsicum plants. Plant J. 2008;56:13–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fry SC. Oxidative scission of plant cell wall polysaccharides by ascorbate-induced hydroxyl radicals. Biochem J. 1998;332:507–515. doi: 10.1042/bj3320507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schopfer P. Hydroxyl radical-induced cell-wall loosening in vitro and in vivo: implications for the control of elongation growth. Plant J. 2001;28:679–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gapper C, Dolan L. Control of plant development by reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:341–345. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem J. 1984;219:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnosky DF, Gagnon ZE, Dickson RE, Coleman MD, Lee EH, Isebrands JG. Changes in growth, leaf abscission and biomass associated with seasonal tropospheric ozone exposures of Populus tremuloides clones and seedlings. Can J For Res. 1996;26:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meir S, Hunter DA, Chen JC, Halaly V, Reid MS. Molecular changes occurring during acquisition of abscission competence following auxin depletion in Mirabilis jalapa. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1604–1616. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai S, Lashbrook CC. Stamen abscission zone transcriptome profiling reveals new candidates for abscission control: enhanced retention of floral organs in transgenic plants overexpressing Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN2. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1305–1321. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.110908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schweikert C, Liszkay A, Schopfer P. Scission of polysaccharides by peroxidase-generated hydroxyl radicals. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:562–570. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mika A, Minibayeva F, Beckett R, Luthje S. Possible function of extracellular peroxidases in stress-induced generation and detoxification of active oxygen species. Phytochem Rev. 2004;3:173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinocur B, Altman A. Recent advances in engineering plant tolerance to abiotic stress: achievements and limitation. Curr Opin Biotech. 2005;16:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bindschedler LV, Dewdney J, Blee KA, Stone JM, Asai T, Plotnikov J, Denoux C, Hayes T, Gerrish C, Davies DR, Ausubel FM, Paul Bolwell G. Peroxidase-dependent apoplastic oxidative burst in Arabidopsis required for pathogen resistance. Plant J. 2006;47:851–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan R, Wu Z, Kostenyuk IA, Burns JK. G-protein-coupled α2A-adrenoreceptor agonists differentially alter citrus leaf and fruit abscission by affecting expression of ACC synthase and ACC oxidase. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:1867–1875. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]