Abstract

Microtubules (MTs), which play crucial roles in normal cell function, are regulated by MT associated proteins (MAPs). Using a combinatorial approach that includes biochemistry, proteomics and bioinformatics, we have recently identified 270 putative MAPs from Drosophila embryos and characterized some of those required for correct progression through mitosis. Here we identify functional groups of these MAPs using a reciprocal hits sequence alignment technique and assign InterPro functional domains to 28 previously uncharacterized proteins. This approach gives insight into the potential functions of MAPs and how their roles may affect MTs.

Keywords: Drosophila, domain, microtubule, MAP, alignment

Introduction

MTs, a constituent of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton, are intracellular protein polymers composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers, which grow and shrink in a highly regulated fashion. Their varied roles within the cell include regulating the division of nuclear material, cell motility and maintaining cell shape and polarity. The precise structure and function of MT populations is governed by MAPs.1 MAPs were originally identified in mammalian brain tissue extracts as proteins which co-sediment with purified tubulin.2 Recently, the term MAPs has been applied to any protein that can associate, directly or indirectly, to MTs in vivo or in vitro. Adaptations of early biochemical co-sedimentation methods have been carried out with some success, identifying a selection of proteins, which co-localize with MTs3 and regulate their organisation.4 The advance of proteomics techniques has opened up the possibility of identifying hundreds of MAPs from a single tissue.5,6

We recently used a co-sedimentation approach to isolate putative MAPs from blastoderm stage Drosophila embryos,7 resulting in the identification of 270 proteins, 83 of which were found to be functionally uncharacterized by Gene Ontology8 (GO) in FlyBase.9 In that study, we analyzed the putative MAPs using a combination of bioinformatics, biochemistry and cell biology, in order to investigate MAP complexes that function during the cell cycle.7

Results and Discussion

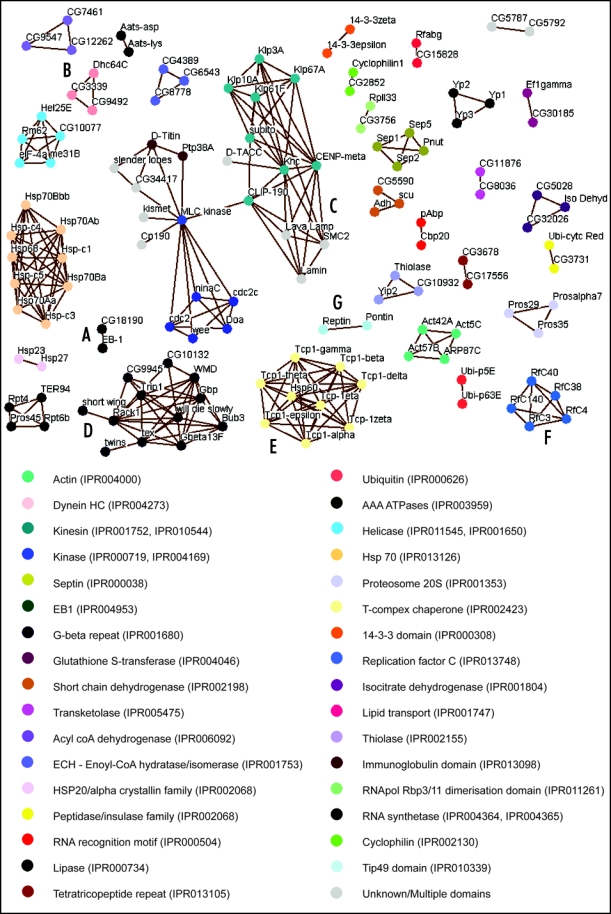

To further investigate the potential roles of the 83 uncharacterized proteins and to identify functional domains within the whole set of MAPs, we have carried out sequence alignments using BLAST.10 Protein sequences were downloaded from FlyBase in FASTA format and each MAP was aligned in turn against every other sequence within our data set. In order to increase the accuracy of homology identification, only hits identified in a reciprocal manner were collected.11,12 Reciprocal alignments can be visualized by edges in a network diagram with proteins as nodes (Fig. 1). Of the 270 proteins aligned, 130 gave a reciprocal alignment to another MAP, 28 of which were novel proteins. Functional categories were then assigned to each group of proteins where a common domain or family was found using PFam13 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(See page 48) Network diagram showing MAPs with aligned sequences. All reciprocally aligned proteins sequences are visualised by way of this network diagram using Osprey version 1.0.1.29 Nodes represent proteins while edges indicate the reciprocal alignment with e-value less than 1E-03. Domains and family groups are identified as InterPro codes30 and all relevant protein domains are listed for each protein (Table S1). Functional domains and families of each protein are indicated by the node coloring defined by the key.

Some well-studied groups of proteins, such as kinases, septins and isoforms of actin and their related proteins, align with one another without the inclusion of novel proteins. However, other groups of MAPs do align with previously uncharacterized proteins. For example, the protein CG18190 aligns with EB-1, a previously identified MAP of the +Tip family that binds specifically to the growing ends of MTs (Fig. 1A).14,15 As expected, CG18190 has been shown to bind to, and localize to MTs in the early embryo, although its precise function remains unclear16 (Hiro Okhura, personal communication). Dynein Heavy Chain (Dhc64C), a subunit of the MT motor protein complex Dynein,17 aligns with two novel MAPs, CG3339 and CG9492 (Fig. 1B). In good agreement, a previous study which searched for Drosophila homologues of over 1000 known cytoskeletal proteins also predicted CG3339 and CG9492 to be Dynein-like motor proteins.18 By demonstrating that they co-sediment with MTs, we support this prediction. Further investigation of these proteins should help elucidate the functional significance of multiple dyneins in the early embryo.

It is worth noting that some well characterized MAPs, such as Lava Lamp19 and D-TACC4 align with the group of kinesin-like proteins and one another, but this cannot be attributed to an identifiable common domain. This may be an indication of a novel functional element that exists between the aligning proteins, and could be of interest in the future. Alternatively, it may be a reflection of overall structural similarity within this class of MAPs; for example, all proteins in this group (Fig. 1C) are predicted to possess coiled-coils.20 These helical secondary structures provide surfaces for protein-protein interactions, and are prevalent in MAPs involved in the regulation of mitosis.21

Another interesting cluster is based on homology between proteins containing G-beta repeats (Fig. 1D), a sub-category of WD-40 repeats, which are also known to be involved in protein-protein interactions.22 While several G-beta repeat-containing proteins, such as the Dynein Intermediate Chain Shortwing,23 Gbeta13F,7 Rack1,24 and Bub3,25 are known to localize to MT populations, the other proteins in this cluster have not been reported to associate with MTs. Our identification of these proteins as MAPs suggests that the G-beta repeat may, like the coiled-coil, occur in many MAPs.

A final aspect of interest is the clustering of proteins that are known to form complexes together. Not surprisingly, our analysis found homology between all TCP-1 subunits; TCP-1 is a tubulin chaperone complex whose constituents have evolved from a single ancestral protein (Fig. 1E).26 In addition, all subunits of the Replication Factor C (RfC) complex fall within a single cluster (Fig. 1F). This heteropentameric complex loads the sliding clamp, PCNA, around DNA27 and the sequence similarity of all five proteins lies in their RfC domain, a class of AAA+ ATPase domain. Why this complex might bind to MTs and what effect this might have upon the MTs themselves, has yet to be investigated. However, it is interesting to note that the Pontin-Reptin complex, whose subunits also possess an AAA+ ATPase domain, the Tip49 domain (Fig. 1G), has recently been shown to interact with tubulin and regulate mitotic spindle assembly.28

Our biochemical approach, teamed with mass spectrometry and bioinformatics, has elucidated 270 novel MAPs. We have successfully categorized 130 of these into functional groups by reciprocal alignments of their protein sequences. Of the 83 previously uncharacterized proteins identified in our screen, 34% (28 proteins) have now been aligned to another MAP, giving insight into their potential functions. It is clear that a collaborative approach such as this has the ability to reveal a wealth of functional data that may not be achievable by individual disciplines. We feel that this work highlights the increasing relevance of computational methods and analyses in the biological scientific community, particularly in handling data on a large scale and making use of the vast quantity of post-genomic data available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiro Okhura for sharing unpublished data. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Oxford Life Sciences Interface/Doctoral Training Centre provided a studentship to Katherine H. Fisher and a lectureship to James G. Wakefield. Charlotte M. Deane was supported by a lectureship associated with the EPSRC Oxford Systems Biology/Doctoral Training Centre and with funding from Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

Abbreviations

- GO

gene ontology

- MT

microtubule

- MAP

microtubule associated protein

- RfC

replication factor C

Addendum to: Hughes JR, Meireles AM, Fisher KH, Garcia A, Antrobus PR, Wainman A, Zitzmann N, Deane C, Ohkura H, Wakefield JG. A microtubule interactome: Complexes with roles in cell cycle and mitosis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:98.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/6795

References

- 1.Cassimeris L, Spittle C. Regulation of microtubule-associated proteins. Int Rev Cyt. 2001;210:163–226. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)10006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borisy GG, Marcum JM, Olmsted JB, Murphy DB, Johnson KA. Purification of tubulin and associated high molecular weight proteins from porcine brain and characterization of microtubule assembly in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975;253:107–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb19196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellogg DR, Field CM, Alberts BM. Identification of microtubule-associated proteins in the centrosome, spindle, and kinetochore of the early Drosophila embryo. J Cell Bio. 1989;109:2977–2991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gergely F, Kidd D, Jeffers K, Wakefield JG, Raff JW. D-TACC: a novel centrosomal protein required for normal spindle function in the early Drosophila embryo. Embo J. 2000;19:241–252. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuong SD, Good AG, Taylor GJ, Freeman MC, Moorhead GB, Muench DG. Large-scale identification of tubulin-binding proteins provides insight on subcellular trafficking, metabolic channeling, and signaling in plant cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:970–983. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400053-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto T, Uezu A, Kawauchi S, Kuramoto T, Makino K, Umeda K, Araki N, Baba H, Nakanishi H. Mass spectrometric analysis of microtubule co-sedimented proteins from rat brain. Genes Cells. 2008;13:295–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes JR, Meireles AM, Fisher KH, Garcia A, Antrobus PR, Wainman A, Zitzmann N, Deane C, Ohkura H, Wakefield JG. A microtubule interactome: complexes with roles in cell cycle and mitosis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. www.geneontology.org.

- 9. www.flybase.org.

- 10.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan IK, Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Essential genes are more evolutionarily conserved than are nonessential genes in bacteria. Genome Res. 2002;12:962–968. doi: 10.1101/gr.87702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu H, Luscombe NM, Lu HX, Zhu X, Xia Y, Han JD, Bertin N, Chung S, Vidal M, Gerstein M. Annotation transfer between genomes: protein-protein interologs and protein-DNA regulogs. Genome Res. 2004;14:1107–1118. doi: 10.1101/gr.1774904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:247–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaughan PS, Miura P, Henderson M, Byrne B, Vaughan KT. A role for regulated binding of p150(Glued) to microtubule plus ends in organelle transport. J Cell Bio. 2002;158:305–319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughan KT. TIP maker and TIP marker; EB1 as a master controller of microtubule plus ends. J Cell Bio. 2005;171:197–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott SL, Cullen CF, Wrobel N, Kernan MJ, Ohkura H. EB1 is essential during Drosophila development and plays a crucial role in the integrity of chordotonal mechanosensory organs. Mol Bio Cell. 2005;16:891–901. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gepner J, Li M, Ludmann S, Kortas C, Boylan K, Iyadurai SJ, McGrail M, Hays TS. Cytoplasmic dynein function is essential in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;142:865–878. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein LS, Gunawardena S. Flying through the Drosophila cytoskeletal genome. J Cell Bio. 2000;150:63–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.f63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sisson JC, Field C, Ventura R, Royou A, Sullivan W. Lava lamp, a novel peripheral golgi protein, is required for Drosophila melanogaster cellularization. J Cell Bio. 2000;151:905–918. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss HM, Keller S. Pharmacological interference with protein-protein interactions mediated by coiled-coil motifs. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2008:461–482. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72843-6_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li D, Roberts R. WD-repeat proteins: structure characteristics, biological function, and their involvement in human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:2085–2097. doi: 10.1007/PL00000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boylan KL, Hays TS. The gene for the intermediate chain subunit of cytoplasmic dynein is essential in Drosophila. Genetics. 2002;162:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skop AR, Liu H, Yates J, 3rd, Meyer BJ, Heald R. Dissection of the mammalian midbody proteome reveals conserved cytokinesis mechanisms. Science. 2004;305:61–66. doi: 10.1126/science.1097931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu J, Logarinho E, Herrmann S, Bousbaa H, Li Z, Chan GK, Yen TJ, Sunkel CE, Goldberg ML. Localization of the Drosophila checkpoint control protein Bub3 to the kinetochore requires Bub1 but not Zw10 or Rod. Chromosoma. 1998;107:376–385. doi: 10.1007/s004120050321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubota H, Hynes G, Carne A, Ashworth A, Willison K. Identification of six Tcp-1-related genes encoding divergent subunits of the TCP-1-containing chaperonin. Curr Biol. 1994;4:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(94)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majka J, Burgers PM. The PCNA-RFC families of DNA clamps and clamp loaders. Prog Nuc Acid Res Mol Bio. 2004;78:227–260. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)78006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ducat D, Kawaguchi S, Liu H, Yates JR, 3rd, Zheng Y. Regulation of Microtubule Assembly and Organization in Mitosis by the AAA+ ATPase Pontin. Mol Bio Cell. 2008;19:3097–3110. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breitkreutz BJ, Stark C, Tyers M. Osprey: a network visualization system. Genome Biol. 2003;4:22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulder NJ, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bradley P, Bork P, Bucher P, Cerutti L, Copley R, Courcelle E, Das U, Durbin R, Fleischmann W, Gough J, Haft D, Harte N, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kanapin A, Krestyaninova M, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Letunic I, Madera M, Maslen J, McDowall J, Mitchell A, Nikolskaya AN, Orchard S, Pagni M, Ponting CP, Quevillon E, Selengut J, Sigrist CJ, Silventoinen V, Studholme DJ, Vaughan R, Wu CH. InterPro, progress and status in 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:201–205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.