Abstract

Recent studies indicate that survivors of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) are at increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease, conditions that healthy dietary patterns may help ameliorate or prevent. To evaluate the usual dietary intake of adult survivors of childhood ALL, food frequency questionnaire data were collected from 72 participants, and compared with the 2007 WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention recommendations, the DASH diet, and the 2005 USDA Food Guide. Mean daily energy intake was consistent with estimated requirements, however mean BMI was 27.1 kg/m2 (overweight). Dietary index scores averaged fewer than half the possible number of points on all three scales, indicating poor adherence to recommended guidelines. No study participant reported complete adherence to any set of guidelines. Although half the participants met minimal daily goals for 5 servings of fruits and vegetables (WCRF/AICR recommendations) and ≤30% of energy as dietary fat (DASH diet and USDA Food Guide), participants reported dietary sodium and added sugar intake considerably in excess of recommendations, and suboptimal consumption of whole grains. Guideline adherence was not associated with either BMI or waist circumference, perhaps due to the low dietary index scores. These findings suggest that dietary intake for many adult survivors of childhood ALL is not concordant with dietary recommendations that may help reduce their risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease or other treatment-related late-effects.

Keywords: diet, survivorship, cancer, dietary guidelines, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer in the United States, with an estimated 2600 children (ages 0-19) newly diagnosed in 2006 1. Advances in the treatment of childhood ALL over the past 30 years have resulted in current 5-year survival rates of nearly 90% for children diagnosed at age 14 years or younger 2. However, ALL therapies place survivors at risk for a variety of treatment-related adverse late effects. We have previously shown that survivors of childhood ALL, particularly those who received cranial radiation therapy (CRT) as part of their treatment regimen, are at increased risk for growth hormone deficiency, central obesity, hyperlipidemia and other components of cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome 3. Healthy diet and physical activity patterns may decrease risk of weight gain and subsequent risk of cardiovascular complications following cancer treatment 4.

Because of a limited research base, no evidence-based dietary guidelines exist for childhood cancer survivors. Current dietary recommendations for cancer survivors mirror those for primary cancer prevention 4, 5. Several groups have issued evidence-based dietary recommendations for prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease over the past decade, including the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) 5, 6, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet guidelines 7, and the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans 8. While the three sets of guidelines are similar in that they advocate diets high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and propose energy intake levels that are appropriate to achieve or maintain a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5-25 kg/m2, each emphasize somewhat different nutritional priorities, and each has relevance to cancer survivors.

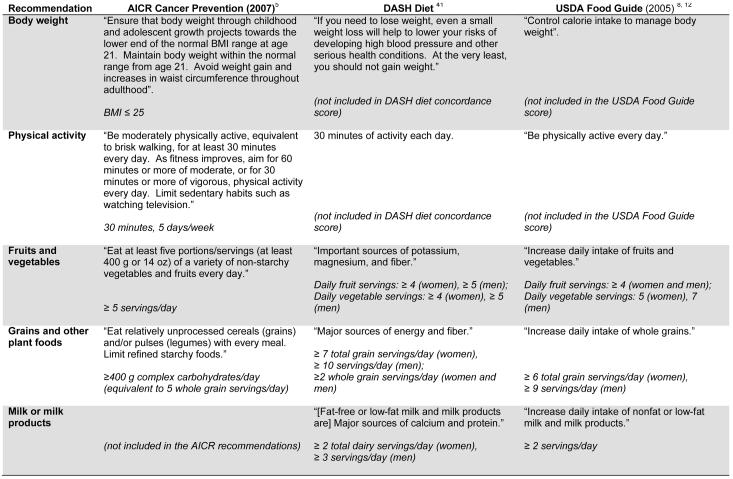

The WCRF/AICR guidelines were updated in 2007 and emphasize the importance of maintaining a healthy weight throughout life as perhaps “one of the most important ways to protect against cancer.” For the first time, the 2007 report includes a section on cancer survivorship, however the expert panel concluded that “in no case is the evidence specifically on cancer survivors clear enough to make any firm judgments or recommendations to cancer survivors”. The 2007 guidelines no longer include specific limits on dietary fat intake, although energy-dense foods (such as dietary fats) are discouraged. The DASH guidelines were originally developed to lower blood pressure, and thus limit dietary sodium, saturated fat and cholesterol, and emphasize foods high in potassium, calcium, and magnesium (fruits, vegetables and low fat dairy products). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, issued by the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Agriculture every 5 years, are designed to promote health and reduce risk of all chronic diseases, including cancer and cardiovascular disease. The most recent report, issued in 2005, refers to both the DASH and USDA Food Guide Pyramid eating plans to guide Americans to specific dietary recommendations at various calorie levels. Figure 1 outlines the specific recommendations for each of the national guidelines.

Figure 1.

Comparison of dietary guidelines (dietary intake level assigned the maximal index point score in italics)

Because interest has been growing in the use of dietary index scores to assess adherence with dietary guidelines 9, scales have been created to describe the degree to which recommendations are met for the WCRF/AICR dietary guidelines 10, the DASH diet 11 and the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (USDA Food Guide) 12. Diet is a complex, multidimensional, chronic exposure which is difficult to accurately measure in epidemiologic studies 9. These index scores provide a method to capture dietary intake as a single summary exposure variable. To date, only a handful of epidemiologic studies have examined the association of disease risk with adherence to these dietary guidelines, and none, to our knowledge, have evaluated the effect of dietary guideline adherence on outcomes among childhood cancer survivors.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the typical dietary intake of adult survivors of childhood ALL, and to determine how their dietary intake compares with major dietary recommendations related to cancer and cardiovascular disease prevention, including the 2007 WCRF/AICR dietary recommendations, the DASH diet concordance score, and the USDA Food Guide. Because obesity is associated with increased risk of chronic disease, including cancer (primary or recurrent)13 and cardiovascular disease 14, we also evaluated whether adherence with dietary guidelines was associated with BMI and waist circumference among adult survivors of childhood ALL.

Materials and Methods

The current results were derived from a clinical study of metabolic syndrome in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia; the study design and methodology have been described in detail elsewhere 3. Briefly, eligibility for this study included being an active participant in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) 15, and having received treatment for ALL at age ≤20 years at the University of Minnesota Children's Hospital or Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minneapolis/St. Paul between 1970 and 1986. A total of 207 individuals met the eligibility criteria for the study and a sample of 75 was targeted for enrollment. Potential participants were stratified into 3 groups by cranial radiation (CRT) dose (none, <24 Gy, ≥24 Gy) in blocks of 25 persons each, assigned a random number within treatment group and block, and contacted in random order until each 25 member treatment group was filled. Twenty-nine (14%) subjects actively or passively refused participation, 22 (10.6%) were lost to follow-up, 10 (4.8%) agreed to participate but were never scheduled because accrual was met, and 71 (34.2%) were not contacted because their random number was not reached in our sampling scheme. No statistically significant differences were found in any socio-demographic or treatment measures between the 75 study participants and the 132 eligible non-participants, with the exception of radiation treatment group and brain radiation field as these were factors in the sampling design (data not shown) 3. Although treated for ALL as children, at the time of this study, all participants were older than age 18 years (range: 19-45). The majority of study participants (95%) were residents of Minnesota or neighboring states at the time of the study. Written informed consent was obtained for each subject as approved by the Human Subjects Review Committees at the University of Minnesota and Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minneapolis/St. Paul.

Height in centimeters was measured with a wall mounted stadiometer, and weight in kilograms was measured using an electronic scale (Model 5002, Scale-Tronix Inc., Wheaton, IL). Body mass index (BMI) was then calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured between the anterior superior iliac spine and the lower rib margin. Hip girth was measured at the maximum hip width over the greater trochanters.

Usual dietary intake over the previous 12 months was assessed during the initial clinic visit at the General Clinical Research Center of the University of Minnesota using the NCI Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) 16. Studies comparing the DHQ instrument to the Block and Willett questionnaires have found the validity of the DHQ to be as good or superior to the other food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) 16, 17. Correlations of energy intake estimates between the DHQ and 24-hour dietary recalls was found to be close to 0.5 for both genders; attenuation coefficients for energy were 0.39 for women and 0.40 for men 16. Participants were not aware of the outcome of their metabolic syndrome evaluation or any other test results when they completed the DHQ. Questionnaire data were analyzed for food groupings and nutrient intake using the Diet*Calc Analysis Software (version 1.4.3, National Cancer Institute, Applied Research Program, November 2005).

Figure 1 lists the underlying recommendations for each of the three dietary index scores, with the maximal possible index point score for each specific dietary intake level listed in italics. The recommendations are based on 2000 kcal/day eating plans for women and 2600 kcal/day for men, which is appropriate for moderately active individuals between the ages of 9 and 50 years according to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 8. Where ranges of servings were recommended, a point was given for reaching the lower end of the range.

An adherence score was formed to determine degree of adherence for each participant to the 2007 WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention Recommendations related to diet. The 2007 update of the WCRF/AICR recommendations resulted in a decrease in the number of personal recommendations from 14 to 8, although this decrease largely results from combining five of the 1997 recommendations relating to food processing into a single recommendation in 2007. Our adherence score operationalizes seven of the eight 2007 WCRF/AICR recommendations. The recommendation not included in our scoring scheme is “Dietary supplements are not recommended for cancer prevention”, although the expert panel reviewing the evidence acknowledged that supplements may be of value during certain illnesses or for repletion of nutrient deficiencies. This recommendation was not included in our score as it would be difficult to determine retrospectively whether dietary supplements were indicated. Participants received one point for meeting each of the other WCRF/AICR recommendations, for a maximal total score of 7.

The DASH diet concordance score was calculated using the methods described by Folsom et al 11. A full point was assigned when a participant met the criteria for each index point listed in Figure 1, with a partial point (0.5) awarded to those whose intake approached, but did not achieve, the recommended intake level. A score of 11 indicates total adherence to the DASH diet recommendations. Similar to nutrient data used by Folsom et al, the DHQ FFQ does not collect intake data in a way that allows for differentiation between fat-free/low-fat dairy products and those with higher fat; therefore, the scoring system evaluates total dairy intake rather than fat-free/low-fat dairy specifically.

The USDA Food Guide score was determined for each participant using the methods described by Dixon et al 12. Participants received a point for achieving the minimum recommended intake for each of the 5 main USDA food groups (grains, dairy, fruits, vegetables, and meat and meat equivalents), with additional points awarded for diets that were < 10% of energy from saturated fat, ≤ 7% of total energy from added sugars, and alcohol intake of ≤2 drinks/day for men, and ≤1 drink/day for women (representing “the discretionary calorie allowance” described in the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans). Total energy from sugars was calculated by multiplying the DHQ variable “teaspoons of added sugars” by 16 (number of calories per teaspoon), and then dividing by total calorie intake. Specific food group serving recommendations based on a 2000 kcal/day eating plan for women and 2600 kcal/day eating plan for men is listed in italics in Figure 1. A score of 8 indicates complete adherence with the USDA Food Guide.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic, treatment, diet and physical activity variables. Analyses were performed for the entire cohort, and by separately for men and women. The association between scores on the DASH and on the USDA Food Guide and both BMI and waist circumference were evaluated in linear regression models, adjusted for age, sex, physical activity level and smoking status. The WCRF/AICR dietary recommendations include a recommendation related to body weight, thus we did not include the WCRF/AICR diet score in the analyses of waist circumference or BMI.

Results

Of the 75 individuals eligible for the present study, 3 did not provide enough information on the DHQ for the questionnaire to be scored. Characteristics of the 72 participants who completed the DHQ are presented in Table 1. Slightly more than half of the study participants were women (n=42, 58%), and all, except one male, were Caucasian (97%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Total cohort |

Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=72) | (N=30) | (N=42) | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p * | |||

| Age at interview, years (Mean, SD) | 29.9 (7.3) | 30.8 (7.51) | 29.3 (7.2) | 0.39 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, years (Mean, SD) | 5.4 (4.3) | 6.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (3.8) | 0.36 | ||

| Years of survival (Mean, SD) | 24.8 (6.9) | 24.4 (4.9) | 25.0 (8.1) | 0.71 | ||

| Radiation treatment group | 0.41 | |||||

| None | 24 (33.3) | 8 (26.7) | 16 (38.1) | |||

| < 24 Gy | 25 (34.7) | 10 (33.3) | 15 (35.7) | |||

| ≥ 24 Gy | 23 (31.9) | 12 (40.0) | 11 (26.2) | |||

| Body areas in radiation fields | 0.30 | |||||

| None | 24 (33.3) | 8 (26.7) | 16 (38.1) | |||

| Brain | 48 (66.7) | 22 (73.3) | 26 (61.9) | |||

| Total body | 5 (6.9) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (9.5) | |||

| Current medications | ||||||

| Testosterone (males) / estrogen (females) | 15 (20.8) | 1 (3.3) | 14 (33.3) | <0.01 | ||

| Antihypertensives | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | NE | ||

| Body composition | ||||||

| BMI kg/m2 (Mean, SD) | 27.1 (6.9) | 26.6 (5.2) | 27.4 (8.0) | 0.61 | ||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.75 | ||

| 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 | 33 (45.8) | 12 (40.0) | 21 (50.0) | |||

| 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 | 17 (23.6) | 10 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) | |||

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 21 (29.2) | 7 (23.3) | 14 (33.3) | |||

| Percent body fat (Mean, SD) | 34.1 (11.1) | 27.1 (8.5) | 39.2 (10.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm; Mean, SD) | 91.1 (15.6) | 92.5 (12.9) | 90.0 (17.3) | 0.51 | ||

| Hip circumference (cm; Mean, SD) | 100.9 (13.5) | 98.3 (11.2) | 102.8 (14.8) | 0.17 | ||

| Smoker (yes: N, %) | 13 (18.1) | 7 (23.3) | 6 (14.3) | 0.33 | ||

Abbreviations: cm=centimeters, Gy = Gray, kg=kilograms, m=meters, N=number, NE = not evaluable, SD=Standard deviation.

From Chi-squared statistic, Fisher's exact test, and one way anova F-test statistic

Dietary intake and physical activity data for the study participants is summarized in Table 2. Mean daily energy intake was estimated to be 2529 kcal/day for men and 1990 kcal/day for women. Although women consumed significantly fewer grams of total fat than did men, there was no statistically significant difference between men and women when total or saturated fat intake was evaluated as a percentage of total energy. Mean energy from fat was 30.6%, which is consistent with the maximum recommended intake on the DASH diet. Similarly, mean energy from saturated fats, at 10.4%, was consistent with the upper recommended limit of both the DASH diet and USDA Food Guide. Thirty-five (49%) of study participants reported ≤30% of calories from total fat, and 32 (44%) of participants reported ≤10% of calories from saturated fat.

Table 2.

Diet and physical activity among the study cohort by sex

| Total cohort | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=72) | (N=30) | (N=42) | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p * | |||

| Diet score (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| AICR § | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.0) | <0.01 | ||

| DASH ‡ | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.4) | 0.80 | ||

| USDA Food Guide † | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.2) | 0.30 | ||

| Nutrient intake, daily (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 2215.0 (1182.4) | 2529.3 (1263.9) | 1990.5 (1080.4) | 0.06 | ||

| Fat (g) | 74.4 (40.6) | 88.7 (46.0) | 65.6 (34.2) | 0.03 | ||

| Energy from fat (%) | 30.6 (8.2) | 31.2 (8.1) | 30.2 (8.4) | 0.59 | ||

| Energy from saturated fat (%) | 10.4 (2.7) | 10.7 (2.6) | 10.1 (2.8) | 0.32 | ||

| Protein (g) | 83.9 (48.6) | 93.0 ((56.7) | 77.4 (41.2) | 0.18 | ||

| Carbohydrate (g) | 290.5 (187.7) | 315.2 (150.4) | 272.8 (210.3) | 0.35 | ||

| Energy from sugar (%) | 16.6 (11.6) | 16.8 (8.0) | 16.5 (13.8) | 0.89 | ||

| Total Fiber (g) | 17.3 (11.0) | 19.3 (11.8) | 16.4 (11.0) | 0.28 | ||

| Sodium (mg) | 3113.4 (1502.1) | 3536.6 (1851.9) | 2811.2 (1121.2) | 0.04 | ||

| Daily food group servings (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| Fruit | 2.9 (4.9) | 2.3 (2.0) | 3.3 (6.2) | 0.31 | ||

| Vegetables | 3.2 (2.3) | 3.5 (2.3) | 2.9 (2.4) | 0.29 | ||

| Total grains | 5.2 (3.1) | 6.3 (3.9) | 4.4 (2.2) | 0.01 | ||

| Whole grains | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.27 | ||

| Dairy | 2.6 (2.5) | 2.8 (3.5) | 2.4 (1.5) | 0.48 | ||

| Meat, poultry, fish (oz) | 4.6 (3.7) | 5.1 (3.1) | 4.3 (4.0) | 0.42 | ||

| Physical activity∥ (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| Total minutes per day | 67.7 (94.4) | 72.2 (74.1) | 64.1 (105.8) | 0.73 | ||

| Total kcal per day | 285.1 (398.2) | 311.1 (354.8) | 264.6 (433.0) | 0.63 | ||

| Leisure time physical activity | 0.24 | |||||

| None (N, %) | 7 (9.7) | 2 (6.7) | 5 (11.9) | |||

| 1-149 minutes per week (N, %) | 52 (72.2) | 20 (66.7) | 32 (76.2) | |||

| ≥ 150 minutes per week (N, %) | 13 (18.1) | 8 (26.7) | 5 (11.9) | |||

| Drink alcohol (yes: N, %) | 7 (9.7) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (9.5) | 0.95 | ||

Abbreviations: AICR=American Institute for Cancer Research, DASH=Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, g=grams, kcal=kilocalories, N=number, SD=Standard deviation, USDA = United States Department of Agriculture.

For normal GH vs. insufficient/deficient GH status. From Chi-squared statistic, Fisher's exact test, and one way anova F-test statistic

Score of 7 indicates complete adherence with the 2007 AICR dietary recommendations for cancer prevention.

Score of 11 indicates total adherence to the DASH diet guidelines.

Score of 8 indicates total adherence to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Includes leisure time physical activity, occupational physical activity, and biking or walking to work

The participants reported a mean energy from added sugars of 16.6%, which is more than double the USDA Food Guide recommendation of ≤ 7% of total daily energy from added sugars. Only 10 participants (14%) met the USDA Food Guide recommendation for added sugars.

Mean sodium intake (3113 mg/day, range: 705-8877) exceeded the maximum daily sodium intake recommendations of 1500 mg (DASH) to 2400 mg (WCRF/AICR). Men reported significantly higher sodium intake (mean: 3537 mg/day) compared with women (2811 mg/day, p = 0.04). It is important to note that these reported sodium intake values likely underestimate actual sodium intake, because the DHQ instrument does not ask respondents about salt added during cooking or at the table. Twenty-five (35%) reported sodium intakes that were ≤ 2400 mg/day.

Evaluation of dietary intake by food groups revealed that half of the study participants were meeting the WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention recommendations for 2 servings of fruit and 3 servings of vegetables/day, but not meeting the higher fruit and vegetable intake recommendations of the DASH diet and the USDA Food Guide. On average, women reported eating more servings of fruits than vegetables, and men reported eating more vegetables than fruits.

Reported intake of both total and whole grains was considerably lower than the recommended number of daily servings on any of the three guidelines. Men reported a daily average of 6.3 servings of total grains and 1.5 whole grains, compared with the recommendations of 9 (USDA) - 10 (DASH) servings of total grains and 2 (DASH) to 5 (WCRF/AICR) servings of whole grains. Similarly, women reported a daily average of 4.4 total grains and 1.2 whole grains, compared with recommendations for 6 (USDA) to 7 (DASH) servings of total grains, and 2 (DASH) to 5 (WCRF/AICR) servings of whole grains. Although not specifically evaluated in any of the three dietary index scores, mean intake of total dietary fiber was 17.3 g/day, which is significantly below the estimated adequate intake for adults 19-50 years old (38 g/day for men and 25 g/day for women) 18. Only 7 participants (10%) met the sex-specific estimated adequate intake levels for dietary fiber.

Mean daily meat intake of 4.6 ounces (oz) in study participants considerably exceeded the WCRF/AICR and DASH diet recommendations of no more than 3 oz (80 g)/day, but was within the 6 oz/day allowances for the USDA Food Guide. Dairy intake, at an average of 2.6 servings/day, met the recommendation for 2 or more servings/day for women (DASH and WCRF/AICR), but fell short of the 3 or more servings/day for men recommended by the DASH dietary guidelines. Fewer than 10% of participants (3 men, 4 women) reported consuming any alcohol.

Participants in our study had relatively low scores on all of the dietary scales. Scores averaged 2.9 out of a possible 7 points for the WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention score (range: 0-6), 3.6 out of a possible 11 points for the DASH diet score (range: 0.5-7.0), and 3.0 out of a possible 8 points for the USDA Food Guide score (1.0-6.0). Women scored higher than men on the DASH and USDA Food Guide scores, however the men scored significantly higher than women on the WCRF/AICR Cancer Prevention score (p <0.01, table 2).

After adjusting for age, sex, physical activity level, and smoking status, compliance with the DASH diet or the USDA Food Guide was not found to be associated with either BMI or waist circumference. However, this is likely due to the relatively poor compliance with any of the dietary scoring patterns in this population.

Discussion

In this study of adult survivors of childhood ALL, we found, in general, that dietary intake was not consistent with dietary recommendations that may help reduce risk of chronic diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease. Although half the participants met minimal goals for fruit and vegetable intake and dietary fat restrictions, participants reported dietary sodium and added sugar intake in excess of recommendations, and suboptimal consumption of dietary fiber.

Mean BMI for the study participants was 27.1 (overweight category) despite the fact that mean estimated energy intake levels were consistent with age- and sex-appropriate estimated requirements according to the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Possible explanations for this discrepancy include: 1) the possibility that FFQs, such as the DHQ, systematically underestimate caloric intake; 2) that study participants underreport their intake; 3) only 18% of participants met recommendations for 30 minutes of physical activity, 5 days/week (Table 2); and 4) the possibility that treatment-related factors, such as radiation induced damage to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, may contribute to altered regulation of energy balance.

Approximately half of our study participants consumed the minimal recommended 5 fruits and vegetables servings per day. This is significantly greater than the population median percentage of adults nationwide (23.2%) and in the state of Minnesota (24.5%) who consumed fruits and vegetable 5 or more times per day, according to 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data 19.

The relatively low dietary index scores among our study participants may, in part, be a reflection of the lack of survivor specific dietary guidelines to guide clinicians, survivors and caregivers on key nutrition messages. The three evidence-based guidelines evaluated in this study each address slightly different nutrition considerations, and each has relevance for the survivor population. The goal of the USDA Food Guide, perhaps the broadest of the three guidelines, is to promote health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases for most individuals 8. The WCRF/AICR recommendations are based specifically on evidence relating to cancer prevention, and as such, do not address dietary fat intake, which may be an issue for cancer survivors at risk for cardiovascular complications. The DASH diet, which is based on evidence relating to blood pressure management, may not seem relevant to cancer survivors, even those with the potential for cardiovascular late-effects. Development of evidence- and risk-based dietary guidelines specifically for cancer survivors would greatly enhance nutrition education efforts in this higher-risk population.

The period surrounding the cancer diagnosis and treatment has been described as a “teachable moment” for positive health behavior 20, including dietary changes. In a cross-sectional study of adult cancer survivors, 40% reported making dietary changes following a cancer diagnosis21. Several studies have found that breast cancer survivors, perhaps the most widely studied group of cancer survivors with regard to dietary behaviors, report higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, and fiber, and lower intake of high-fat foods after their cancer diagnosis22, 23, especially in the first five years24. However, one smaller study reported no change in fruit and vegetable intake, and an increase in dietary fat between diagnosis and two years after a breast cancer diagnosis25.

Adult survivors of childhood cancers may have different attitudes and beliefs towards healthy lifestyle behaviors compared with individuals diagnosed with cancers as adults. For adult survivors of childhood cancers, the initial “teachable moment” occurred in a much earlier developmental life stage. A study of adult survivors of childhood cancer found that 46% did not believe that they were at risk for health problems as a result of their cancer treatment, and 19% did not know whether they were at risk 26. Other studies indicate that childhood cancer survivors are at increased risk of lower educational achievement 27 and adverse socioeconomic status 28, and are less likely to be married 29, factors which have also been associated with suboptimal health behaviors and lifestyle.

Previous research on health behaviors among childhood cancer survivors has focused primarily on cancer screening practices, alcohol use, and smoking 30-34. These studies generally indicate that while survivors of childhood cancers do not meet all health recommendations, they are more likely than siblings or age-matched peers to meet recommendations for cancer screening, limiting the use of alcohol, and smoking avoidance 35. In our study, only 7 participants (10%) reported any alcohol use, however 13 participants (18%) reported being a current smoker. Reported alcohol consumption within our study sample is considerably lower than that of the general population of Minnesota, where 64.7% of respondents to the 2005 BRFSS survey reported having had at least one drink of alcohol within the past 30 days (56.2% nationwide) 19. The prevalence of current smokers within our study cohort is consistent with BRFSS prevalence data for Minnesota, where 20% of respondents report being a current smoker 19.

Only two previous studies have described the diet of survivors of childhood cancers. Butterfield et al 36 found that among 541 adult survivors of childhood cancers who were current smokers and enrolled in a smoking cessation study, 68% consumed red meat more than 3-4 times/week, 68% were not taking a daily multivitamin, 29% received fewer than 150 minutes/week of moderate physical activity, and 8% consumed more than recommended amounts of alcohol. Since the study was conducted solely among survivors enrolled in a smoking cessation program, it does not provide information on the dietary behaviors of cancer survivors who do not smoke or to smokers not interested in quitting.

In a study that included 209 adult and pediatric cancer survivors (several types of cancer, age at time of interview: 11-33 years), Demark-Wahnefried et al 37 found that cancer survivors reported diets with fewer than the recommended number of fruit and vegetable servings (mean: 3.4/day), but more frequent than national averages for similar age groups reported in the BRFSS. The average percent of calories from fat was 33.6%. Dietary fiber and alcohol intake were not assessed. In our study, focused exclusively on adult survivors of childhood cancers, participants reported a higher number of daily fruit and vegetable servings, and lower average percent calories from fat.

One of the primary limitations of the current study was the small sample size. Also, although FFQs are one of the more economical methods for collecting dietary data, there are several limitations to using FFQs as dietary assessment instruments 38. FFQs are known to be imprecise, especially with regard to energy 39 and dietary fiber 40 assessment. Most FFQ instruments, including the DHQ, do not assess salt added during cooking or at the table. These concerns are balanced against the strengths of this study. In particular, this study focused on a homogenous group of study participants who were all treated for the same disease. The study did not include an evaluation of the participants' motivations or beliefs toward dietary change, however future research should include evaluation of health knowledge and beliefs to expand our understanding of potential intervention mediators.

In conclusion, this study suggests that in addition to the perhaps better known health messages regarding the need to maintain a healthy body weight and eat more fruits and vegetables, cancer survivors may benefit from instruction to lower dietary sodium and sugar intake, and increase their dietary fiber intake. Prospective intervention trials are needed to establish evidence- and risk-based dietary guidelines for preventing obesity, cardiovascular disease and other treatment-related late effects among adult survivors of childhood cancers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R21-CA106778, M01-RR00400, U24-CA55727, K23-CA85503) and the Children's Cancer Research Fund

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. American Cancer Society, Inc; Atlanta: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute . Incidence-SEER 9 Regs Public Use, November 2004 sub (1973-2002) National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; 2004. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program ( www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database.www.seer.cancer.gov [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Sibley SD, et al. Metabolic syndrome and growth hormone deficiency in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;107:1301–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, et al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:323–53. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. AICR; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, nutrition and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research; Washington, DC: 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th Edition Washington, DC: Jan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kant AK. Dietary patterns and health outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:615–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerhan JR, Potter JD, Gilmore JM, et al. Adherence to the AICR cancer prevention recommendations and subsequent morbidity and mortality in the Iowa Women's Health Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of Concordance With DASH Diet Guidelines and Incidence of Hypertension and Fatal Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon LB, Subar AF, Peters U, et al. Adherence to the USDA Food Guide, DASH Eating Plan, and Mediterranean dietary pattern reduces risk of colorectal adenoma. J Nutr. 2007;137:2443–50. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McTiernan A. Obesity and cancer: the risks, science, and potential management strategies. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:871–81. discussion 81-2, 85-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. (NIH Publication No. 98-4083).National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. 1998 September; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–39. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires : the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–99. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, et al. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: results of an experimental validation study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:212–25. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine . Panel on Macronutrients, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C.: 2002. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, et al. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, et al. Changes in diet, physical activity, and supplement use among adults diagnosed with cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:323–8. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson CA, Flatt SW, Rock CL, et al. Increased fruit, vegetable and fiber intake and lower fat intake reported among women previously treated for invasive breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:801–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maskarinec G, Murphy S, Shumay DM, et al. Dietary changes among cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:12–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skeie G, Hjartaker A, Lund E. Diet among breast cancer survivors and healthy women. The Norwegian Women and Cancer Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:1046–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wayne SJ, Lopez ST, Butler LM, et al. Changes in dietary intake after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1561–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1832–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, et al. Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97:1115–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council . Childhood Cancer Survivorship. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rauck AM, Green DM, Yasui Y, et al. Marriage in the survivors of childhood cancer: a preliminary description from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:60–3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<60::aid-mpo11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao ML, Guo MD, Weiss R, et al. Smoking in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:219–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larcombe I, Mott M, Hunt L. Lifestyle behaviours of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1204–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeazel MW, Oeffinger KC, Gurney JG, et al. The cancer screening practices of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2004;100:631–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castellino SM, Casillas J, Hudson MM, et al. Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: a comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6499–507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emmons KM, Butterfield RM, Puleo E, et al. Smoking among participants in the childhood cancer survivors cohort: the Partnership for Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:189–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulhern RK, Tyc VL, Phipps S, et al. Health-related behaviors of survivors of childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;25:159–65. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950250302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butterfield RM, Park ER, Puleo E, et al. Multiple risk behaviors among smokers in the childhood cancer survivors study cohort. Psychooncology. 2004;13:619–29. doi: 10.1002/pon.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demark-Wahnefried W, Werner C, Clipp EC, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer and their guardians: current health behaviors and receptivity to health promotion programs. Cancer. 2005;103:2171–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristal AR, Peters U, Potter JD. Is it time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2826–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-ED1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schatzkin A, Kipnis V, Carroll RJ, et al. A comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with a 24-hour recall for use in an epidemiological cohort study: results from the biomarker-based Observing Protein and Energy Nutrition (OPEN) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1054–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hudson TS, Forman MR, Cantwell MM, et al. Dietary fiber intake: assessing the degree of agreement between food frequency questionnaires and 4-day food records. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:370–81. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Facts about the DASH eating plan. 2007 March; Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/introduction.html; Accessed.