Abstract

Suberin, a cell specific, wall-associated biopolymer, is formed during normal plant growth and development as well as in response to stress conditions such as wounding. It is characterized by the deposition of both a poly(phenolic) domain (SPPD) in the cell wall and a poly(aliphatic) domain (SPAD) thought to be deposited between the cell wall and plasma membrane. Although the monomeric components that comprise the SPPD and SPAD are well known, the biosynthesis and deposition of suberin is poorly understood. Using wound healing potato tubers as a model system, we have tracked the flux of carbon into the aliphatic monomers of the SPAD in a time course fashion. From these analyses, we demonstrate that newly formed fatty acids undergo one of two main metabolic fates during wound-induced suberization: (1) desaturation followed by oxidation to form the 18:1 ω-hydroxy and dioic acids characteristic of potato suberin, and (2) elongation to very long chain fatty acids (C20 to C28), associated with reduction to 1-alkanols, decarboxylation to n-alkanes and minor amounts of hydroxylation. The partitioning of carbon between these two metabolic fates illustrates metabolic regulation during wound healing, and provides insight into the organization of fatty acid metabolism.

Key Words: suberin, potato, Solanum tuberosum, carbon flux analysis, abiotic stress

Introduction

During the course of evolution, plants have developed a variety of strategies to protect themselves against desiccation. One of the strategies is the formation of suberin, a cell specific, wall-associated biopolymer, during plant growth and development as well as in response to stress conditions such as wounding (reviewed in ref. 1), where it serves as a physical barrier to protect against water loss and pathogen attack. Suberin occurs in dermal cells of underground tissues, the Casparian band, bundle sheath cells and in the cork cells of bark tissue2 and is characterized by the deposition of both a poly(phenolic) domain (SPPD) in the cell wall and a poly(aliphatic) domain (SPAD) between the cell wall and plasma membrane (reviewed in ref. 3).

Using relatively simple analytical tools such as organic solvent extraction, hydrolysis (including BF3/MeOH transesterification, reduction with LiAlH4 and alkaline hydrolysis with NaOCH3 or NaOH) and subsequent GC-MS analysis, the composition of the SPAD and its associated waxes has generally become completely known. The known monomers of the SPAD include 1-alkanols, ω-hydroxyalkanoic acids, α,ω-dioic acids, mid-chain epoxide- and di- and tri-hydroxy-substituted octadecanoates, very long chain fatty acids and glycerol.4–7 However, only sketchy details are known about their biosynthesis. For example, the oxidation of 16-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid, to form an α,ω-dioic acid, has been demonstrated to be catalyzed by a soluble NADH-dependent dehydrogenase in suberizing potatoes.8–10 However, the ω-hydroxylation step has not been demonstrated in suberizing tissues, even though it has in cutinizing systems11–18 including the ω-hydroxylation of both fatty acids and their 9,10-epoxide-and 9,10-dihydroxylated derivatives by CYP86A18 and CYP94A16 members. The latter of these, a cytochrome P450 from Nicotiana tabacum, has been demonstrated to catalyze the complete sequence of reactions oxidizing the ω-carbon of a variety of fatty acids from a methyl group to a carbonyl group.16

With respect to the elongation process, besides the initial demonstration of the incorporation of [14C] acetate into very long chain fatty acids,19 a fatty acid elongase from the primary roots of corn (Zea mays L.) seedlings has been characterized and its activity measured.20,21 The major products found were elongated fatty acids with chain lengths ranging from C20 to C24. Preferred substrates were 18:0 and 20:0 acyl-CoAs, whereas monounsaturated acyl-CoAs (C16:1 and C18:1) and acyl-CoAs of lower (C12–C16) and higher chain lengths (C22–C24) were rarely elongated.21

While these enzymatic and molecular studies provide some details of the biosynthesis of a few monomers of cutin and the SPAD, they are targeted, in part, on the basis of the analysis of aliphatic monomers released from mature suberin and cutin polymers, and do not necessarily address issues of timing, metabolic flux or metabolic regulation. Consequently, we consider it critical to take a more global approach to study the biosynthesis of the monomers that make up the SPAD. In the present investigation, we present a detailed time course analysis of the formation of suberin aliphatics by monitoring the dynamic change of both organic solvent extractable (i.e., soluble) aliphatics and their incorporation into the insoluble SPAD, using wound healing potato tuber as a model system. This work allows us to monitor suberin aliphatic metabolism more globally, and provides a more dynamic description of the flux of carbon through this pathway during the biosynthesis of suberin aliphatics.

Materials and Methods

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv. Russet Burbank) tubers were grown at the Environmental Sciences Western field station of the University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, and stored at 5°C in the dark until used. Chromatographic standards (n-alkanes, 1-alkanols and FAMEs), 14% BF3 in methanol (BF3/MeOH) and BSTFA (99% + 1% TMCS) were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich Company. Solvents were of reagent grade.

Isolation of potato wound periderm.

Surface-sterilized potato tubers were cut (i.e., wounded) transversely into ca. 0.5 cm thick slices under sterile conditions and incubated in Magenta® boxes for up to seven days. The suberizing layers were collected as described,22 immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C until used.

Analysis of membrane lipids.

Membrane lipids were isolated from suberizing tissue and separated by TLC (AL SIL G / UV254, 0.25 mm layer, 20 × 20 cm, Whatman), using choloroform as the developing solvent.23 Molybdenum blue spray and α-naphthol stain were used to identify phospholipids and glycolipids, respectively. The membrane-associated aliphatics were scraped from TLC plates, recovered by chloroform/methanol (2:1), dried down under a stream of nitrogen and transesterified with BF3/MeOH at 70°C for 3 h. The methylated sample was extracted with chloroform and again dried under a stream of nitrogen, dissolved in a small volume of pyridine (typically 50 µL) and trimethylsilylated with an equal volume of BSTFA (99% + 1% TMCS) at 70°C for 40 min. The combined methyl ester/TMS ether derivatives were analysed on Varian CP-3800 Gas Chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and an ion trap mass spectrometer (GC-MS). The GC was equipped with a pair of CP-Sil 5 CB Low bleed MS columns (WCOT silica 30 m × 0.25 mm ID): one in line with the FID and the other with the MS. The injector ovens were set at 250°C, and the FID oven at 300°C. Samples (1 µL) were injected twice (once to each column) in splitless mode and simultaneously eluted with the following oven temperature program: 70°C for 2 min, 40°C/min to 200°C, hold 2 min, 3°C/min to 300°C, hold 9.42 min, total 50 min. High purity helium was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. Compounds were identified by comparison of their EI-mass spectra to either the spectra of authentic standards generated on our system or published mass spectra.18,24–26 Quantification of identified compounds was done with GC-FID, using both an internal standard (triacontane) and external calibration curves derived from authentic standards.

Analysis of soluble lipids.

Soluble lipids were extracted from suberizing tissue according to Dean and Kolattukudy,19 with some modification. In brief, the suberizing tissue was exhaustively extracted in a micro-Soxhlet extractor twice with chloroform-methanol (2:1) (3.5 h × 2) followed by an overnight extraction with chloroform. The combined extracts were concentrated in vacuo at <40°C, acidified to pH 2–3 with 1 N HCl and extracted with an equal volume of chloroform three times. The pooled chloroform extracts were concentrated in vacuo at <40°C, transferred to a small vial, dried under a stream of nitrogen and derivatised and analysed by GC-FID/GC-MS as above. Three independent time course studies were conducted with triplicate samples taken at each time point in each study.

Analysis of the insoluble poly(aliphatic) fraction.

BF3/MeOH transesterification27–29 was used to hydrolyze the tissue residue remaining after Soxhlet extraction, releasing formerly esterified components as their methyl esters or free alcohols. Samples were further trimethylsilylated as above and the derivatised compounds analyzed by GC-FID/GC-MS as above. Two sub-samples were taken for transesterification from each sample of extractive free tissue (i.e., six samples per time point per time course).

Carbon flux calculations.

The total carbon flux (d(Ci)/dt), without correction for growth-related changes in mass, was calculated for each day during the process of suberization, according to Morgan and Shanks,30 where C is the yield of aliphatics (µmol/cm2), t is the time (days) and i is the identifier for each aliphatic.

Results

Wound-induced changes in aliphatic metabolism.

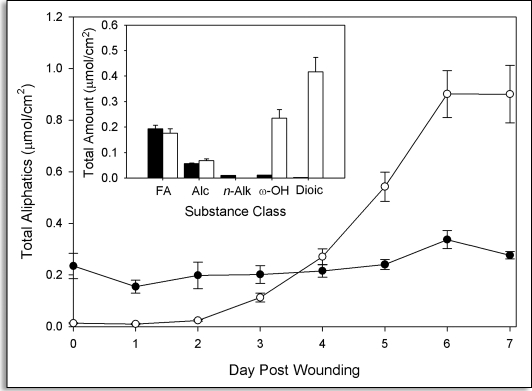

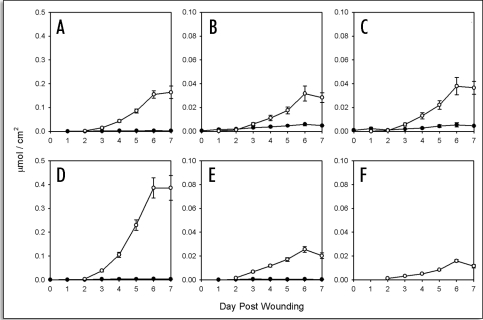

Upon wounding, new aliphatics are synthesized and accumulate in the surface layers of potato tubers (Fig. 1). These new aliphatics can be separated into soluble and insoluble (SPAD) components on the basis of how they are isolated. The total amount of soluble aliphatic compounds remained relatively constant throughout the time course period, whereas their incorporation into the insoluble SPAD was evident after a two-day lag. Eventually, the bulk of the newly synthesized aliphatics accumulate in the SPAD (Fig. 1). The main substance classes measured include fatty acids (C16 to C28), 1-alkanols (C16 to C28), n-alkanes (C21, C23 and C25), ω-hydroxy-alkanoic acids (C18:1, C22 and C24) and α,ω-dioic acids (C16, C18:1, C18:2) (Fig. 1, inset), as previously described for suberins.4,29 In addition, very small amounts of 2-hydroxytetracosanoic acid (C24) (eg. up to 0.0066 ± 0.0004 µmol/cm2 by day seven post wounding).

Figure 1.

Time course analysis of the accumulation of aliphatics in suberizing potato tissue. The total amount of aliphatic components (µmol/cm2) released by Soxhlet extraction (closed symbols) and BF3/MeOH transesterfication of extractive-free cell wall residues (open symbols) are shown separately. Three independent time course studies were conducted with triplicate samples (two sub-samples for polymeric aliphatics) taken at each time point in each study. Error bars represent one standard deviation. Inset: The distribution of the main substance classes in both soluble (black bar) and SPAD (white bar) pools, including fatty acids (FA), 1-alkanols (Alc), n-alkanes (n-Alk), ω-hydroxyalkanoic acids (ω-OH) and α,ω-dioic acids (Dioic), compiled from data collected seven days post wounding.

Membrane lipids analysis.

The soluble aliphatics extracted from suberizing potato tubers represent three pools: membrane-associated fatty acids, suberin waxes and those aliphatics targeted for polymerization into the SPAD. In order to help distinguish these three pools, a separate analysis of membrane-associated fatty acids was undertaken. Thus, using TLC, membrane lipids (glycolipids and phospholipids) were separated from other soluble aliphatics, hydrolyzed and analyzed by GC-FID/GC-MS. Using this method, palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0), oleic (18:1) and linoleic/linolenic (18:2/3) acids were identified as membrane lipid components of suberizing potato tissue, consistent with literature data.31 The amounts and mole ratio of these components remained relatively constant throughout the time course (Table 1). Moreover, only very small amounts of these fatty acids were identified in SPAD hydrolysates (Fig. 2A–D), suggesting that they are not major components of suberin. The amounts of these fatty acids could therefore be subtracted from the total amounts of soluble aliphatics to provide an estimate of those fatty acids involved in the biosynthesis of the SPAD or its associated waxes.

Table 1.

Membrane lipid composition of suberizing tissue

| Membrane | Day Post Wounding | ||||||||

| Component | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16:0 | 12a | 15 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 13 (17)b |

| 18:1 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 13 (6) |

| 18:0 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 (5) |

| 18:2/18:3 | 75 | 68 | 71 | 69 | 69 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 70 (72) |

Total membrane lipids were separated from organic solvent soluble aliphatics by TLC and the fatty acid composition determined by GC-FID. Values presented represent the relative weight percent of each compound.

Values represent the mean of triplicate samples analysed for each time point.

Numbers in brackets are from Galliard T. 1973.

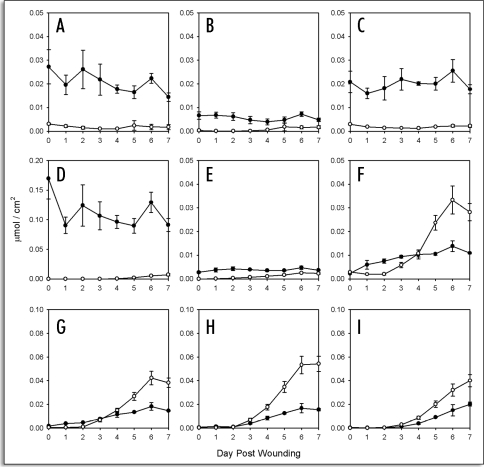

Figure 2.

Time course accumulation of fatty acids in suberizing potato tissue. Amounts (µmol/cm2) released by Soxhlet extraction (closed symbols) and BF3/MeOH transesterfication of extractive-free cell wall residues (open symbols) are shown separately for (A) 16:0, (B) 18:0, (C) 18:1, (D) 18:2/18:3, (E) 20:0, (F) 22:0, (G) 24:0 (H) 26:0 and (I) 28:0 fatty acids. Data points represent the mean of three independent time course studies, each with triplicate samples (two sub-samples for polymeric aliphatics) taken at each time point. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Accumulation patterns of induced aliphatics.

Fatty acids. Fatty acids ranging in chain length from C16 to C28 were detected in both soluble and insoluble aliphatic extracts (Fig. 2A–I). As noted above, the shorter chain fatty acids (C16, C18) are primarily derived from membranes and are largely found in the soluble extracts. Fatty acids >C20 were found in greater abundance in the insoluble fraction, especially at later times post wounding (Fig. 2F–I). In general a one to three day lag in accumulation of long chain fatty acids in the insoluble fraction was evident, with very long chain fatty acids showing the longest lag (compare Fig. 2F and I).

1-Alkanols. 1-Alkanols ranging in chain length from C16 to C28, including two with odd-numbered chain lengths (C19 and C21) were detected in both soluble and insoluble fractions (Fig. 3A–I) except C21 (Fig. 3E), which was only detected in the soluble fraction. Of these, the very long chain components (e.g., C26, C28) were in greatest abundance. As with the fatty acids, there was a one to three day lag in the accumulation of most 1-alkanols, especially the longer chain components.

Figure 3.

Time course accumulation of 1-alkanols in suberizing potato tissue. Amounts (µmol/cm2) released by Soxhlet extraction (closed symbols) and BF3/MeOH transesterfication of extractive-free cell wall residues (open symbols) are shown for (A) 16:0, (B) 18:0, (C) 19:0, (D) 20:0, (E) 21:0, (F) 22:0, (G) 24:0 (H) 26:0 and (I) 28:0 1-alkanols. Data points represent the mean of three independent time course studies, each with triplicate samples (two sub-samples for polymeric aliphatics) taken at each time point. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

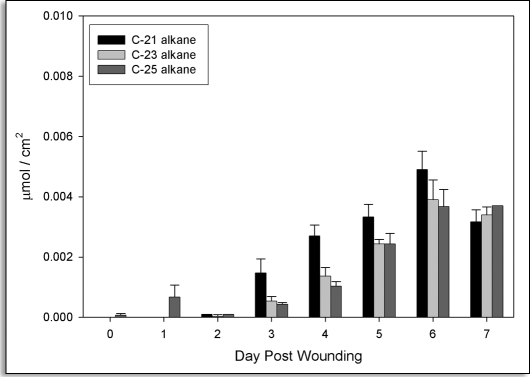

n-Alkanes. n-Alkanes (C21, C23 and C25) were only detected in soluble extracts, reflecting their role as part of GHI the waxes associated with suberized tissues.32,33 They were present in very low amounts until approximately three days post wounding, after which they accumulated steadily (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Time course accumulation of n-alkanes in suberizing potato tissue. Amounts (µmol/cm2) released by Soxhlet extraction are shown for C21 (black bars), C23 (light grey bars) and C25 (grey bars) n-alkanes. Data points represent the mean of three independent time course studies, each with triplicate samples taken at each time point. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

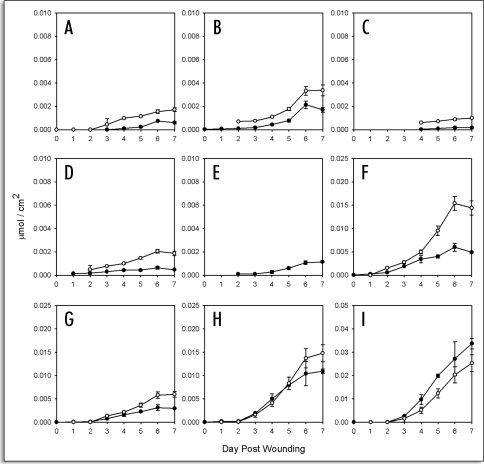

ω-hydroxy fatty acids. Only very low amounts of ω-hydroxy fatty acids were detectable in the soluble fraction, including 18:1, 22:0 and 24:0 components, at any time post wounding (Fig. 5A–C). By contrast, 18-hydroxy-octadecenoic acid was the second most abundant compound in the BF3/MeOH depolymerisate, especially at later times post wounding (compare Fig. 5A and D). Despite the apparent lack of accumulation of ω-hydroxy fatty acids in the soluble fraction, their incorporation into the SPAD was rapid after a two to three day lag period. The rate of incorporation (ca. 0.05 µmol/day/cm2) remained constant between day three and six post wounding.

Figure 5.

Time course accumulation of ω-hydroxy fatty acids and α,ω-dioic acids in suberizing potato tissue. Amounts (µmol/cm2) released by Soxhlet extraction (closed symbols) and BF3/MeOH transesterfication of extractive-free cell wall residues (open symbols) are shown for (a) 18-hydroxyoctadecenoic, (b) 22-hydroxydocosanoic, and (c) 24-hydroxytetracosanoic acid, as well as (d) octadecen-1,18-dioic, (e) octadecadien-1, 18-dioic and (f) hexadecan-1, 16-dioic acid. Data points represent the mean of three independent time course studies, each with triplicate samples (two sub-samples for polymeric aliphatics) taken at each time point. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

α,ω-dioic acids. Only trace amounts of α,ω-dioic acids, including 18:1 and 18:2 components, were found in the soluble fraction (Fig. 5D–F). This is in stark contrast to the BF3/MeOH depolymerisate where octadecen-1,18-dioic acid was released in the greatest abundance compared to all other SPAD components (Fig. 5D). The incorporation of α,ω-dioic acids into the SPAD occurred after a lag of two to three days and was constant (ca. 0.1 µmol/day/cm2) between three and six days post wounding.

Carbon flux analysis.

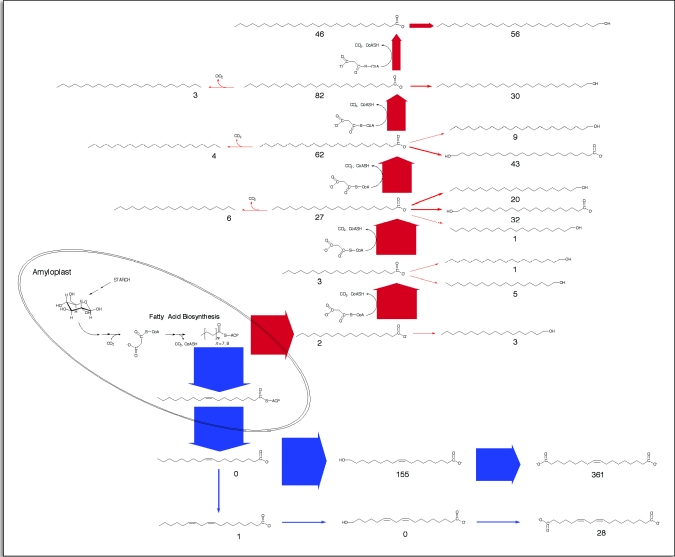

Using the identity of isolated aliphatic components as a guide, we first constructed a biogenic scheme for suberin aliphatics, placing each compound in the most logical position relative to all other aliphatics, taking into account their (presumed) biosynthetic origin from stored starch (Fig. 6). Next we calculated the total flux (d(Ci)/dt), for each aliphatic compound, where C is the yield of aliphatics (µmol.cm−2), t is the time (days) and i represents each aliphatic, according to its position in our biogenic scheme. As indicated above, the contribution of membrane-associated 16:0, 18:0, 18:1 and 18:2/3 fatty acids was subtracted from the data before daily increments were calculated. Based on these flux data, the relative proportion of each type of biochemical process (e.g., desaturation, elongation, oxidation, reduction) could be determined. For example, the relative proportion of 16:0 and 18:0 emerging from the fatty acid synthetase (FAS) complex was relatively constant, with the latter accounting for >90% throughout the wound healing process (Fig. 7A).

Figure 6.

Biosynthetic scheme for the formation of suberin aliphatic monomers. Starting with carbon stored as starch, the biosynthesis of fatty acids is depicted as an amyloplast-based process, leading to (primarily) stearic (18:0) acid-ACP. The metabolic fate of stearate (as it relates to suberin aliphatic monomer biosynthesis) is arranged according to the most logical sequence based on structural relationships leading to the aliphatic monomers found in the soluble and SPAD pools. For example, the elongation of stearate into VLCFAs is depicted as a separate pathway from its desaturation to oleic acid-ACP since the latter leads almost exclusively to 18-hydroxyoctadecenoic and octadecen-1,18-dioic acids. By contrast, VLCFAs accumulate as free acids, become reduced (or oxidized) to primary alcohols or are oxidized to n-alkanes. Unusual ω-hydroxylated VLCFAs are presumed to be the products of VLCFA oxidation, rather than chain-elongated ω-hydroxy acids (see text). The thickness of arrows indicates the relative flux through each step, based on time course data collected four days post wounding. Numerical values beside individual compounds represent the number of that type of molecule per 1000 total aliphatic molecules that accumulated by day four post wounding. For clarity, palmitate-derived components (20/1000) are not shown. No attempt has been made to depict the subcellular location of reactions beyond fatty acid biosynthesis and stearic acid desaturation, although fatty acid elongation is known to be ER-associated. Similarly, the transport of fatty acids out of the amyloplast, their activation (e.g., with coenzyme-A) and involvement in phospholipids metabolism are not shown.

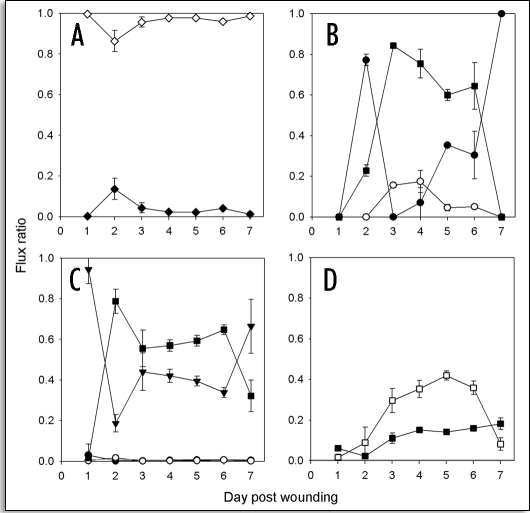

Figure 7.

Carbon flux through C16 and C18 aliphatics during SPAD biosynthesis. The ratios (distribution) of flux (A) between C16 and C18 aliphatics, (B) within C16 aliphatics, and (C) within C18 aliphatics, are shown. Symbols indicate: total C16 aliphatics (filled diamonds), total C18 aliphatics (open diamonds), fatty acids with no further modification (filled circles), 1-alkanols (open circles), fatty acids that are further elongated (filled, inverted triangles), and ω-hydroxy fatty & dioic acids (filled squares). (D) Relative amounts of 18:1 ω-hydroxy (filled squares) and 18:1 dioic (open squares) acids in comparison with all aliphatics. Note that the data represent the total flux (soluble + SPAD) of carbon and do not distinguish between that which will remain soluble and that which will become fixed in the SPAD. Data points represent the average of flux ratios calculated individually for three independent time course studies. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Flux analysis of the small amount of 16:0 fatty acids released from the FAS complex revealed that these were largely converted into ω-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid and hexadecan-1, 16-dioic acid, beginning two days post wounding, and dropping off sharply again between day six and seven post wounding (Fig. 7B). Aside from a small proportion of flux into 1-hexadecanol (especially between day two and five post wounding), the remaining 16:0 was otherwise unmodified.

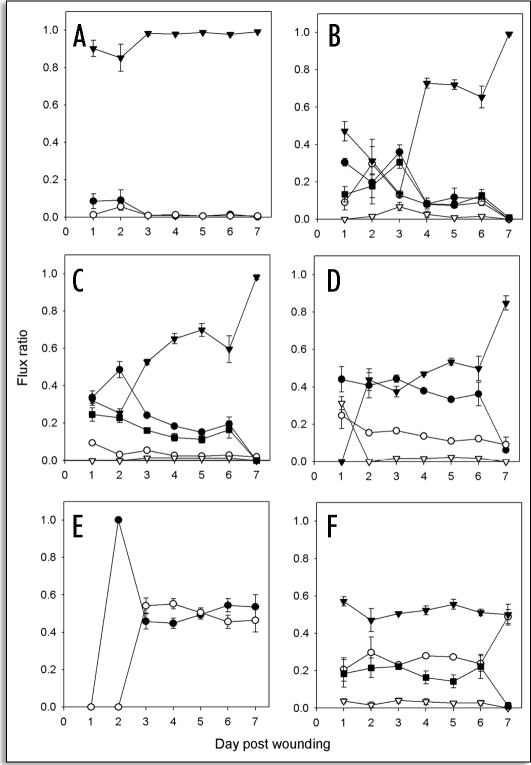

Figure 8.

Carbon flux through elongated suberin aliphatics during SPAD biosynthesis. The ratios (distribution) of flux between (A) C20, (B) C22, (C) C24, (D) C26 and (E) C28 groups of aliphatics and (f) overall distribution amongst different classes of modified, elongated aliphatics, are shown. Symbols indicate: fatty acids with no further modification (filled circles), 1-alkanols (open circles), fatty acids that are further elongated (filled, inverted triangles), n-alkanes (inverted triangles) and ω-hydroxy fatty acids (filled squares). Note that the data represent the total flux (soluble + SPAD) of carbon and do not distinguish between that which will remain soluble and that which will become fixed in the SPAD. Data points represent the average of flux ratios calculated individually for three independent time course studies. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Flux analysis of the 18:0 fatty acids released by the FAS complex revealed that these were largely partitioned between two disparate metabolic fates: desaturation followed by ω-hydroxylation and oxidation to the octadecen-1,18-dioic acid (Fig. 7C and D) and elongation to very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) (Fig. 7C). Initially, the elongation of 18:0 accounted for nearly all the flux in the 18:0 pathway. However, between two and three days post wounding a steady state distribution of carbon between elongation and desaturation pathways was evident, with the latter accounting for a slightly greater amount until between day six and seven post wounding, when flux through the desaturation pathway (including ω-hydroxylation and oxidation to the octadecen-1,18-dioic acid) dropped sharply.

The flux of carbon into the 20:0 family of aliphatics resulted mainly in further elongation, with a relatively small flux (<10%) into 1-eicosanol during the first two days of wound healing (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the flux of carbon into 22:0 fatty acids was partitioned between further elongation and modification into 1-docosanol, 22-hydroxydocosanoic acid and a C-21 alkane during the early stages of wound healing, while the flux shifted toward elongation only during the later stages (Fig. 8B). The flux into 24:0 fatty acids showed a similar pattern, with the flux of carbon into the elongation pathway becoming more prominent with time (Fig. 8C).

By contrast, a steady state level of carbon flux into 26:0 fatty acids was observed, throughout the time course of wound healing, except for between days six and seven, when flux declined sharply (Fig. 8D). As with the 20:0, 22:0 and 24:0 fatty acids, the flux of carbon into further elongation reactions increased with the duration of wound healing, but remained in a steady state for four days prior to rising sharply. The flux of carbon into 1-hexacosanol remained in steady state throughout the time course of wound healing, as did that into pentacosane, except at day one, where it was disproportionately high, leading to a delay of 26:0 fatty acid accumulation and subsequent elongation (Fig. 8D). Similarly, the flux of carbon into 28:0 fatty acids was constant throughout the time course, albeit after a two-day lag. Further conversion into 1-octacosanol was evident by day three with a steady state of carbon into both compounds for the remainder of the time course (Fig. 8E).

Analysis of the overall flux distribution amongst different classes of elongated aliphatics revealed that >50% remained as VLCFAs, with the remainder roughly equally divided between reduction to 1-alkanols and oxidation to ω-hydroxy-acids. Steady state flux through these classes of aliphatic compounds was observed, until between days six and seven, when the flux towards ω-hydroxylation dropped off with a corresponding increase in the flux toward the biosynthesis of 1-alkanols (Fig. 8F). A very small proportion of elongated aliphatics were converted into alkanes.

Discussion

Upon wounding, potato tubers undergo a massive re-allocation of carbon from starch reserves into new cell wall components, including aliphatics destined for the SPAD. And while wound healing potato tubers represent a good model system to study many aspects of suberin formation, it was not feasible to conduct pulse-chase experiments (with either stable-or radio-labeled substrates) beyond two to three days of wound healing since the developing suberin layer prohibits the uptake of exogenously supplied metabolites. However, the formation of new aliphatics during wound healing results in compounds that essentially represent end products of lipid metabolism that for all intents and purposes do not turn over (with the possible exception of new membrane lipids). Consequently, we adopted the biogenic flux analysis approach described by Morgan and Shanks30 for our analysis. For this, we constructed a biogenic scheme placing the main suberin aliphatic monomers in the most logical arrangement based on their structural relationships (Fig. 6). For example, since n-alkanes and 1-alkanols are products of fatty acid metabolism, chain elongation is shown to precede decarboxylation and reduction reactions leading to these products. Similarly, stearic acid (18:0) desaturation to oleic acid (18:1) is shown to precede ω-hydroxylation. The unusual ω-hydroxylated VLCFAs were presumed to be the products of VLCFA oxidation, rather than chain-elongation of (shorter chain) ω-hydroxy acids, since (1) there are no ω-hydroxylated and unsaturated VLCFAs, and (2) the majority (>97%) of the shorter chain ω-hydroxylated fatty acids are otherwise unsaturated (i.e., 18:1, 18:2), with the remainder being 16:0.

From our biogenic scheme it became obvious immediately that newly synthesized fatty acids emerging from FAS were predominantly 18:0 (>90%) and that this carbon was being partitioned between two distinct metabolic fates: (1), desaturation followed by ω-hydroxylation and oxidation to the octadecen-1,18-dioic acid and (2) elongation to VLCFAs coupled with limited reduction (to yield 1-alkanols), decarboxylation (to yield n-alkanes) and oxidation (to yield ω-hydroxy and 2-hydroxy fatty acids).

Total carbon flux analysis showed that the elongation process began earlier than desaturation during the early stages of suberization, although monomer biosynthesis remained low at that time. During later stages of suberization, the carbon partition between the elongation and desaturation was almost equal. Since all wound-induced SPAD aliphatics are (presumably) derived from glucose, (i.e., as a product of starch degradation), we calculated that for every gram of dried, mature suberized tissue (which contains 0.08 g SPAD aliphatics), 0.14 g glucose was metabolized into aliphatics and incorporated into the SPAD.

Upon examination of the accumulation patterns of aliphatics in both the soluble pools and the SPAD (Figs. 2–5), it is apparent that long chain alkanoic acids (Fig. 2) and alkanols (Fig. 3) accumulate prior to their incorporation into the SPAD. By contrast, the amounts of 18-hydroxy-octadecenoic and octadecen-1,18-dioic acids (Fig. 5) were only found in trace amounts in the soluble pool despite being major components in the SPAD. These observations raise interesting questions about the spatial and temporal details of ω-hydroxylation and the subsequent oxidation of ω-hydroxy-fatty acids to their corresponding dioic acids. One possibility is the very fast transfer and incorporation of these compounds into the SPAD once they have been synthesized. Alternatively, the ω-hydroxylation of fatty acids and/or their subsequent oxidation to dioic acids may occur as a post-incorporation modification. For example, since the SPAD is thought to be located between the plasma membrane and the cell wall (reviewed in ref. 3), it is possible that ω-hydroxylation may occur at the plasma membrane after the incorporation of oleic acids into the SPAD. Subsequent oxidation of ω-hydroxy-fatty acids to their corresponding dioic acids could also occur outside the membrane as the dehydrogenases responsible have been localized to soluble enzyme preparations from suberizing potato tuber disks.10 This interpretation of the data remains speculative and awaits direct experimental evidence.

Both saturated long chain and 18:1 ω-hydroxy acids were found in both soluble and SPAD pools. However, the relative amount of 18:1 ω-hydroxylation was ca. 10-fold greater than that of VLCFAs during the most metabolically active phase of SPAD monomer synthesis (i.e., days 4 to 6 post wounding), suggesting that the process is favored for shorter chain, unsaturated substrates. At this time it is not possible to distinguish between the possibility of specific ω-hydroxylases for oleic (18:1) and VLCFAs or one multi-substrate ω-hydroxylase with different hydroxylation efficiencies. Since the desaturation of stearic acid occurs in plastids, and the primary fate of oleic acid during normal fatty acid metabolism is its incorporation into diacylglycerols (DAGs) and ultimately phospholipids,34,35 it is tempting to speculate that ω-hydroxylation may be closely associated with DAG biosynthesis. In other words, the partitioning of fatty acids between desaturation and elongation processes during wound-induced suberization may be determined in part by the relative incorporation of newly synthesized fatty acids into DAGs compared with their export to the cytoplasm and subsequent elongation by ER-associated enzymes.

In conclusion, our time course analysis of the accumulation pattern of suberin aliphatics in both the soluble pool and the SPAD, combined with carbon flux analysis, provide a more global picture of the biosynthesis of suberin aliphatics during active suberization. Two significant findings are worth noting: (1) there is a clear partitioning of carbon between two pathways, one leading to elongated fatty acids (with and without further modification to n-alkanes, 1-alkanols and other hydroxylated VLCFAs) and the other leading to octadecenes with further ω-carbon oxidation; and (2) ω-carbon oxidation and the subsequent incorporation of ω-hydroxy-fatty acids and α,ω-dioic acids in to the SPAD occurs very rapidly, with little accumulation of intermediates. This latter finding in particular was only evident after a detailed time course analysis of aliphatic accumulation, and would not be predicted from typical end point analyses. Furthermore, the apparent rapid incorporation of ω-hydroxy-fatty acids and α,ω-dioic acids into the SPAD raises questions about the sub-cellular location of the ω-hydroxylase involved.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to M.A.B.

Abbreviations

- SPAD

suberin poly(aliphatic) domain

- SPPD

suberin poly(phenolic) domain

- FAME

fatty acid methyl ester

- BSTFA

N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)-trifluoroacetamide

- TMCS

trimethylchlorosilane

- VLCFA

very long chain fatty acid

- FAS

fatty acid synthetase complex

- DAG

diacyl glycerol

Footnotes

Previously published onlinse as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/abstract.php?id=2433

References

- 1.Bernards MA, Lewis NG. The macromolecular aromatic domain in suberized tissue: A changing paradigm. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:915–933. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)80052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esau K. Anatomy of Seed Plants. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernards MA. Demystifying suberin. Can J Bot. 2002;80:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holloway PJ. Some variations in the composition of suberin from the cork layers of higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:495–502. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graca J, Pereira H. Cork suberin: A glyceryl based polyester. Holzforschung. 1997;51:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmutz A, Jenny T, Amrhein N, Ryser U. Caffeic acid and glycerol are constituents of the suberin layers in green cotton fibers. Planta. 1993;189:453–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00194445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmutz A, Jenny T, Ryser U. A caffeoyl-fatty acid-glycerol ester from wax associated with green cotton fiber suberin. Phytochemistry. 1994;36:1343–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal VP, Kolattukudy PE. Mechanism of action of a wound-induced ω-hydroxyfatty acid:NADP oxidoreductase isolated from potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum L.) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;191:466–478. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal VP, Kolattukudy PE. Purification and characterization of a wound-induced ω-hydroxyfatty acid:NADP oxidoreductase from potato tuber disks (Solanum tuberosum L.) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;191:452–465. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal VP, Kolattukudy PE. Biochemistry of suberization. ω-hydroxyacid oxidation in enzyme preparations from suberizing potato tuber disks. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:667–672. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.4.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soliday CL, Kolattukudy PE. Biosynthesis of cutin. ω-hydroxylation of fatty acids by a microsomal preparation from germinating vicia faba. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:1116–1121. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.6.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benveniste I, Salaun JP, Simon A, Reichhart D, Durst F. Cytochrome P 450 ω-hydroxylation of lauric acid by microsomes from pea seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:122–126. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinot F, Salaun JP, Bosch H, Lesot A, Mioskowski C, Durst F. ω-hydroxylation of Z-9-octadecenoic, Z-9,10-epoxystearic and 9,10-dihydroxystearic acids by microsomal cytochrome P450 systems from vicia sativa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:183–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91176-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinot F, Bosch H, Alayrac C, Mioskowski C, Vendais A, Durst F, Salaun JP. ω-hydroxylation of oleic acid in vicia sativa microsomes: Inhibition by substrate analogs and inactivation by terminal acetylenes. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1313–1318. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tijet N, Helvig C, Pinot F, Bouquin RL, Lesot A, Durst F, Salaun JP, Benveniste I. Functional expression in yeast and characterization of a clofibrate-inducible plant cytochrome P450 (CYP94A1) involved in cutin monomers synthesis. Biochem J. 1998;332:583–589. doi: 10.1042/bj3320583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouquin RL, Skrabs M, Kahn R, Benveniste I, Salaün JP, Schreiber L, Durst F, Pinot F. CYP94A5, a new cytochrome P450 from nicotiana tabacumis able to catalyze the oxidation of fatty acids to the ω-alcohol and to the corresponding diacid. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3083–3090. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellesen K, Durst F, Pinot F, Beneviste I, Nettesheim K, Wisman E, Streiner-Lange S, Saedler H, Yephremov A. Functional analysis of the LACERATA gene of Arabidopsis provides evidence for different roles of fatty acid ω-hydroxylation in development. PNAS. 2001;98:9694–9699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171285998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao F, Goodwin SM, Xiao Y, Sun Z, Baker D, Tang X, Jenks MA, Zhou JM. Arabidopsis CYP86A2 represses pseudomonas syringae type III genes and is required for cuticle development. EMBO J. 2004;23:2903–2913. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean BB, Kolattukudy PE. Biochemistry of suberization: Incorporation of [1-14C]oleic acid and [1-14C]acetate into the aliphatic components of suberin in potato tuber disks (Solanum tuberosum L.) Plant Physiol. 1977;59:48–54. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreiber L, Skrabs M, Hartmann K, Becker D, Cassagne C, Lessire R. Biochemical and molecular characterization of corn (zea mays L.) root elongases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:647–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiber L, Franke R, Lessire R. Biochemical characterization of elongase activity in corn (zea mays L.) roots. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernards MA, Lewis NG. Alkyl ferulates in wound healing potato tubers. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3409–3412. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83695-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouser G, Kritchevsky G, Simon G, Nelson GJ. Quantitative analysis of brain and spinach leaf lipids employing silicic acid column chromatography and acetone for elution of glycolipids. Lipids. 1967;2:37–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02531998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolattukudy PE, Agrawal VP. Structure and composition of aliphatic constituents of potato tuber skin (suberin) Lipids. 1974;9:682–691. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alderson NL, Rembiesa BM, Walla MD, Bielawska A, Bielawski J, Hama H. The human FA2H gene encodes a fatty acid 2-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48562–48568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonaventure G, Beisson F, Ohlrogge J, Pollard M. Analysis of the aliphatic monomer composition of polyesters associated with arabidopsis epidermis: Occurrence of octadeca-cis-6, cis-9-diene-1,18-dioate as the major component. Plant J. 2004;40:920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riederer M, Schoenherr J. Quantitative gas chromatographic analysis of methyl esters of hydroxy fatty acids derived from plant cutin. J Chromatogr. 1986;360:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riederer M, Schoenherr J. Covalent binding of chemicals to plant cuticles: Quantitative determination of epoxide contents of cutins. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1988;17:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matzke K, Riederer M. A comparative study into the chemical constitution of cutins and suberins from Picea abies (L.) Karst., Quercus robur L., and Fagus sylvatica L. Planta. 1991;185:233–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00194066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan JA, Shanks JV. Quantification of metabolic flux in plant secondary metabolism by a biogenetic organizational approach. Metab Eng. 2002;4:257–262. doi: 10.1006/mben.2002.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galliard T. Lipids of potato tubers. I. lipid and fatty acid composition of tubers from different varieties of potato. J Sci Food Agric. 1973;24:617–622. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740240515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soliday CL, Kolattukudy PE, Davis RW. Chemical and ultrastructural evidence that waxes associated with the suberin polymer constitute the major diffusion barrier to water vapor in potato tuber (Solanum tuberosum L.) Planta. 1979;146:607–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00388840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiber L, Franke R, Hartmann K. Wax and suberin development of native and wound periderm of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and its relation to peridermal transpiration. Planta. 2005;220:520–530. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post-Beittenmiller D. Biochemistry and molecular biology of wax production in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somerville C, Browse J. Dissecting desaturation: Plants prove advantageous. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:148–153. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]