Abstract

The use of the weak base Cs2CO3 in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-protected γaminoalkenes with aryl bromides leads to greatly increased tolerance of functional groups and alkene substitution. Substrates derived from (E)- or (Z)-hex-4-enylamines are stereospecifically converted to 2,1′-disubstituted pyrrolidine products that result from suprafacial addition of the nitrogen atom and the aryl group across the alkene. Transformations of 4-substituted pent-4-enylamine derivatives proceed in high yield to afford 2,2-disubstituted products, and cis-2,5- or trans-2,3-disubstituted pyrrolidines are generated in good yield with excellent diastereoselectivity from N-protected pent-4-enylamines bearing substituents at C1 or C3. The reactions tolerate a broad array of functional groups, including esters, nitro groups, and enolizable ketones. The scope and limitations of these transformations are described in detail, along with models that account for the observed product stereochemistry. In addition, deuterium labeling experiments, which indicate these reactions proceed via syn-aminopalladation of intermediate palladium(aryl)(amido)complexes regardless of degree of alkene substitution or reaction conditions, are also discussed.

Introduction

Substituted pyrrolidines are common motifs displayed in a wide array of interesting biologically active compounds, including natural products and pharmaceutically relevant molecules.1 Due to the significance of pyrrolidine derivatives, a large number of methods have been developed for their synthesis.1a,2 However, few existing methods effect closure of the pyrrolidine ring with concomitant formation of a C–C bond and a stereocenter adjacent to the ring.3 In addition, the invention of new methods for pyrrolidine synthesis that can be used to prepare many different analogs from a common precursor has great potential utility in medicinal chemistry applications.

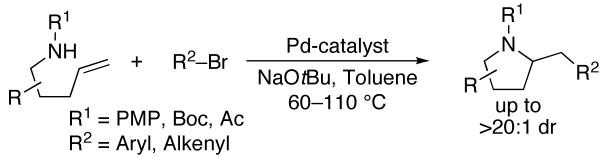

Over the past several years, our group has developed and explored a new method for the synthesis of substituted pyrrolidines via Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-substituted γ-aminoalkenes with aryl/alkenyl halides (eq 1).4,5,6 These transformations effect the construction of the pyrrolidine ring with simultaneous formation of one C–N bond, one C–C bond, and up to two stereocenters from simple precursors.3 In addition, this method can easily be used to generate many different analogs from a single alkene substrate, as a large number of aryl, heteroaryl, and alkenyl halides are readily available.

|

(1) |

Despite the utility of these transformations, the original reaction conditions employed the strong base NaOtBu as a reagent, which led to several significant limitations. For example, many common functional groups such as esters, nitro groups, or enolizable ketones were not tolerated under the strongly basic conditions. In addition, the scope of this method was usually limited to substrates bearing terminal alkenes, as almost all attempted transformations of disubstituted alkenes either resulted in competing base-mediated substrate decomposition or formation of complex mixtures of regioisomers.7,8

We recently reported the discovery of mild conditions for Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-protected γ-aminoalkenes, in which the strong base NaOtBu is replaced with the weak base Cs2CO3. These conditions significantly expand the scope of the carboamination method by allowing the use of functionalized aryl halide coupling partners.9 In this Article we describe our full studies on the development, scope, and limitations of Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions conducted under these new conditions. In addition to illustrating improved functional group tolerance, these studies demonstrate that transformations of disubstituted alkenes can now be achieved when an appropriate catalyst system is employed. We also present experiments that provide additional evidence for our previously described mechanistic hypothesis,5 which involves alkene syn-aminopalladation as a key step in the catalytic cycle. These experiments suggest the pyrrolidine products are formed through a common mechanism regardless of the degree of alkene substitution or the nature of the base (NaOtBu vs. Cs2CO3).

Results

Optimization Studies

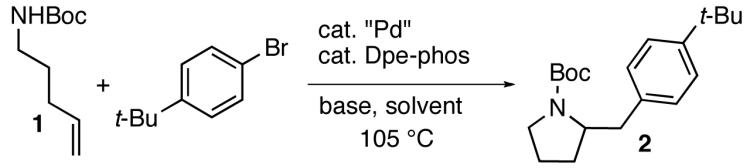

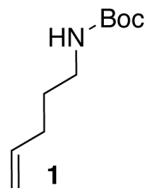

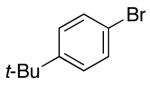

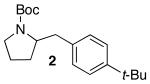

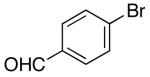

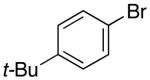

In order to develop mild conditions for Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions we initially examined the coupling of a simple substrate, N-Boc-4-pentenylamine (1), with an electron-neutral aryl bromide (4-bromo-tert-butylbenzene) in the presence of a catalyst composed of Pd2(dba)3/Dpe-phos.10 As shown in Table 1, this transformation afforded 2 in 81% yield using our original, strongly-basic, conditions (NaOtBu, toluene, 105 °C). A number of organic and inorganic bases were screened under otherwise similar reaction conditions, and disappointing results were obtained. In general, use of organic bases (e.g. Et3N) failed to provide any of the desired product, and most inorganic bases were also ineffective, although small amounts of 2 were occasionally observed.11 The most promising results were obtained with Cs2CO3, but the yield of 2 was still modest (38%, entry 2).12

Table 1.

Summary of Reaction Optimizationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Base | “Pd” | Solvent | Yield |

| 1 | NaO tBu | Pd2(dba)3 | Toluene | 81% |

| 2 | Cs2CO3 | Pd2(dba)3 | Toluene | 38% |

| 3 | Cs2CO3 | Pd(OAc)2 | Toluene | 63% |

| 4 | Cs2CO3 | Pd(OAc)2 | Dioxane | 82%b |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv substrate, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 2.3 equiv base, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3 (2 mol % Pd) or 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 2 mol % Dpe-phos (with Pd2(dba)3) or 4 mol % Dpe-phos (with Pd(OAc)2), solvent (0.25 M), 105 °C, 17–27 h (reaction times are unoptimized).

The reaction was conducted at 100 °C.

In order to further optimize conditions with Cs2CO3 as base, we examined the effect of other reaction parameters. We quickly discovered that use of Pd(OAc)2 in place of Pd2(dba)3 provided significantly improved yields (63%, entry 3). After conducting reactions in several different solvents, we arrived at much improved conditions in which 2 was obtained in 82% yield when dioxane was used as solvent (entry 4).13

Studies on Scope and Limitations

Reactions of Terminal Alkene Substrates

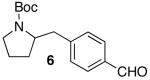

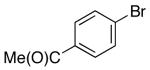

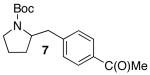

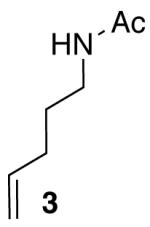

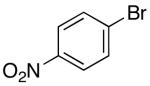

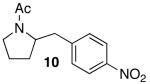

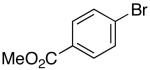

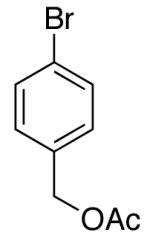

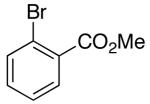

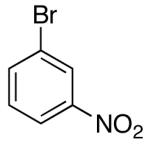

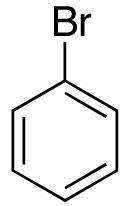

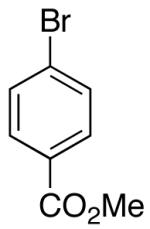

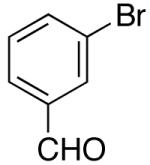

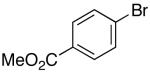

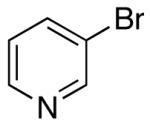

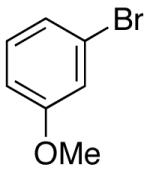

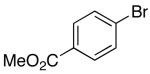

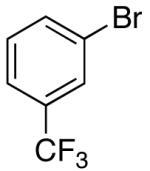

Having successfully optimized conditions for the coupling of 1 with 4-bromo-tert-butylbenzene, we proceeded to explore the utility of these conditions for transformations of different substrate combinations. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, a number of N-protected 4-pentenylamine derivatives are effectively converted to 2-benzylpyrrolidines in good yield. Although the functional group tolerance of Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions is modest when NaOtBu is used as base, a broad variety of functional groups are tolerated with the new, mild reaction conditions. As shown below, aldehydes, enolizable ketones, nitro groups, methyl esters, and alkyl acetates can be incorporated into the pyrrolidine products. In addition, the carboamination reactions of electron-rich, electron-neutral, and heterocyclic aryl bromides proceed with good chemical yields. However, use of dppe10 as ligand was necessary to suppress competing N-arylation when 4-bromonitrobenzene was used as a coupling partner (Table 2, entry 7).

Table 2.

Palladium-Catalyzed Carboamination of N-Protected γ–Aminoalkenes with Functionalized Aryl Bromidesa

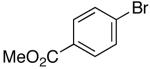

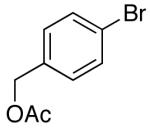

| Entry | Amine | Aryl bromide | Product | Rxn. Time (h) |

Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

|

15 11 |

75 (77) c,e |

| 2 | 1 |  |

|

27 26 |

82 (81) c,e |

| 3 | 1 |  |

|

20 | 78 d |

| 4 | 1 |  |

|

18 | 76 d |

| 5 | 1 |  |

|

28 | 71 |

| 6 |  |

|

|

18 15 |

79 (72) c,e |

| 7 | 3 |  |

|

18 | 76 d,f |

| 8 |  |

|

|

16 18 |

88 (17)c |

| 9 | 4 |  |

|

18 | 88 d |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 2.3 equiv Cs2CO3, 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 4 mol % Dpe-phos, dioxane (0.2–0.25 M), 100–105 °C.

Yield refers to average isolated yield obtained in two or more experiments.

NaO tBu was used in place of Cs2CO3 and toluene was used as solvent.

The reaction was conducted at 85 °C in DME solvent.

Pd2(dba)3 was used in place of Pd(OAc)2.

Dppe was used in place of Dpe-phos.

Table 3.

Palladium-Catalyzed Carboamination of Substituted N-Protected γ–Aminoalkenes with Functionalized Aryl Bromidesa

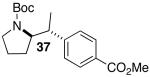

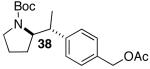

| Entry | Amine | Aryl bromide | Product | dr | Rxn. Time (h) |

Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

|

12:1 | 20 | 80 |

| 2 |  |

|

|

15:1 | 16 | 76 |

| 3 | 14 |  |

|

14:1 | 18 | 73 |

| 4 |  |

|

|

>20:1 | 16 | 75 |

| 5 |  |

|

|

>20:1 | 18 | 74 |

| 6 |  |

|

|

>20:1 | 23 18 |

71 (62) c,d |

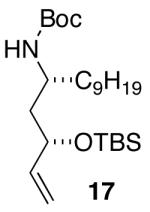

| 7 | 17 |  |

|

>20:1 | 20 | 73 |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 2.3 equiv Cs2CO3, 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 4 mol % Dpe-phos, dioxane (0.2–0.25 M), 100 °C.

Yield refers to average isolated yield obtained in two or more experiments.

NaO tBu was used in place of Cs2CO3 and toluene was used as solvent.

Pd2(dba)3 was used in place of Pd(OAc)2.

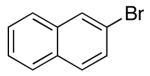

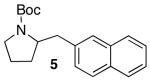

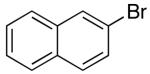

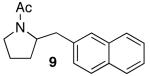

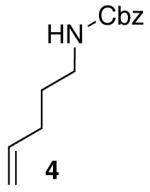

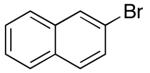

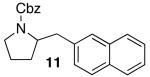

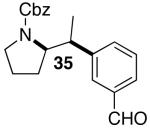

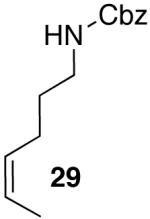

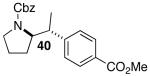

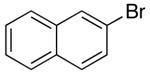

Reactions of unfunctionalized aryl bromides with N-Boc- or N-acyl-4-pentenylamine (1 or 3) provided similar yields regardless of whether NaOtBu or Cs2CO3 was used as base (Table 2, entries 1, 2, and 6). However, the new reaction conditions provided excellent results for the carboamination of Cbz-protected substrate 4 with 2-bromonaphthalene (88% yield of 11, entry 8), whereas use of NaOtBu for this transformation provided only 17% yield of 11. Cleavage of the Cbz-group from the substrate was problematic when the reaction was conducted with the stronger base.

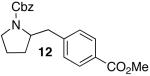

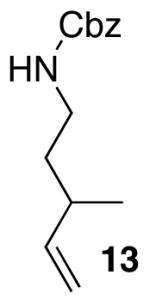

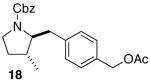

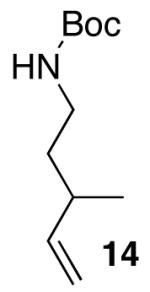

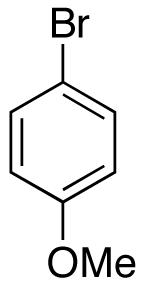

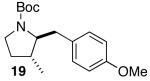

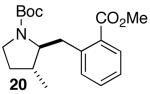

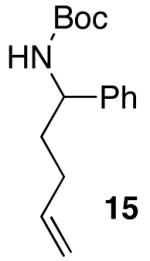

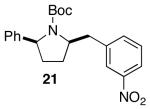

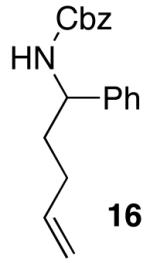

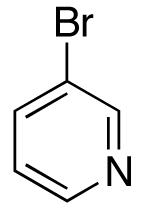

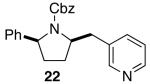

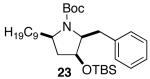

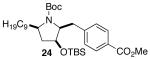

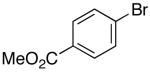

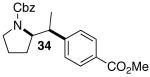

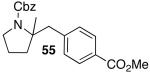

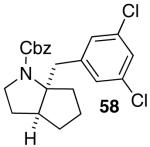

The mild conditions are also effective for stereoselective reactions of N-Boc-and N-Cbz-protected 4-pentenylamine derivatives bearing substituents adjacent to the nitrogen atom and/or adjacent to the alkene. For example, substrates 13 and 14, which are substituted at the allylic position, were converted to trans-2,3-disubstituted pyrrolidines 18–20 with 12 to 15:1 diastereoselectivity (Table 3, entries 1–3).14 The synthesis of cis-2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidine products 21 and 22 was achieved in good yields and >20:1 diastereoselectivity through carboamination of substrates 15 and 16, which are substituted adjacent to the nitrogen atom (entries 4–5). The coupling of 17 with bromobenzene provided 23, which is an intermediate in the synthesis of the natural product preussin,5g in 71% yield with >20:1 dr (Table 3, entry 6). Similarly good results were obtained for the coupling of 17 with methyl-4-bromobenzoate (Table 3, entry 7).

Reactions of Hex-4-enylamine Derivatives

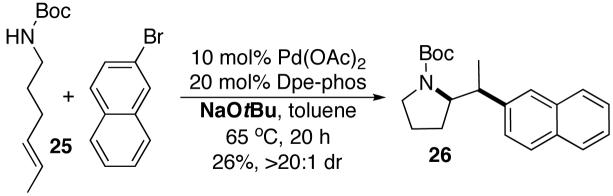

Palladium-catalyzed carboamination reactions of substrates bearing internal alkenes are of considerable potential utility, as these transformations would create two new contiguous stereocenters in one step. However, efforts to convert these substrates to substituted pyrrolidines under conditions in which NaOtBu was used as a base were largely unsuccessful. Pd-catalyzed reactions of aryl bromides with hex-4-enylamines bearing N-aryl substituents provided complex mixtures of products,5a and transformations involving N-Boc-protected substrates proceeded in low yield. For example, treatment of (E)-alkene 25 with 2-bromonaphthalene and NaOtBu in the presence of the Pd(OAc)2/Dpe-phos catalyst afforded only 26% yield of 26 (eq 2).15,16

|

(2) |

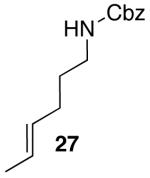

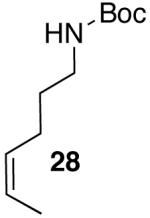

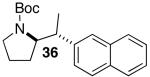

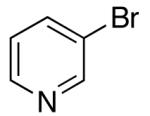

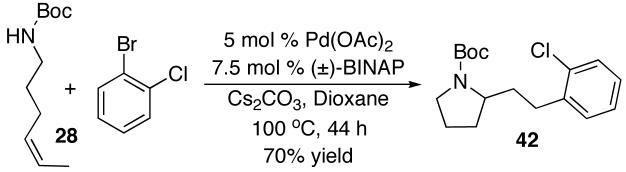

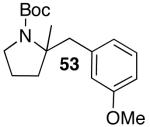

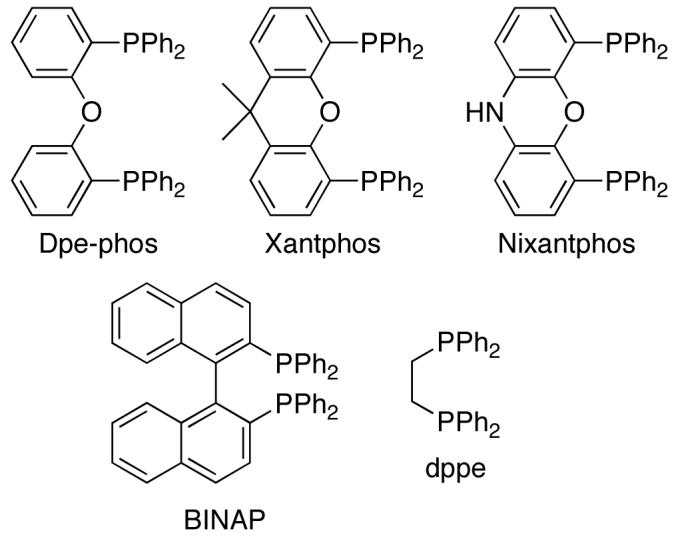

In order to improve the efficiency of reactions involving acyclic internal alkene substrates, we investigated the cyclization of 25 using Cs2CO3 as base and dioxane as solvent. After considerable screening, we were gratified to find that use of Nixantphos10 as ligand led to the conversion of 25 to pyrrolidine product 26, which results from suprafacial addition across the alkene, in 59% yield with >20:1 dr (Table 4, entry 1). Although Nixantphos provided the best results for the coupling of 25 with 2-bromonaphthalene, subsequent experiments indicated that use of (±)-BINAP as ligand provided the best results for most systems examined. Side products resulting from competing N-arylation of the substrate were usually formed in lesser amounts with BINAP than Nixantphos.

Table 4.

Carboamination of N-Protected Hex-4-enylaminesa

| Entry | Amine | Aryl bromide |

Product | Rxn. Time (h) |

Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

|

23 | 59 |

| 2 | 25 |  |

|

36 | 50 |

| 3 | 25 |  |

|

44 | 44 e |

| 4 |  |

|

|

42 | 43 e,f |

| 5 | 27 |  |

|

30 | 43 e,f, g |

| 6 |  |

|

|

27 | 55 e |

| 7 | 28 |  |

|

21 | 55 e |

| 8 | 28 |  |

|

31 | 60 e,h |

| 9 | 28 |  |

|

53 | 62 e |

| 10 |  |

|

|

53 | 49 e |

| 11 | 29 |  |

|

53 | 44 e,g |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 2.3 equiv Cs2CO3, 5 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 7.5 mol % Nixantphos, dioxane (0.25 M), 100 °C.

Yield refers to average isolated yield obtained in two or more experiments. All reactions proceeded with >20:1 diastereoselectivity.

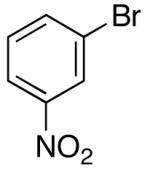

Ar = 3-nitrophenyl.

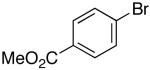

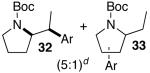

Ar = 4-carbomethoxyphenyl.

(±)-BINAP used in place of Nixantphos.

A trace amount (ca. 1–5%) of a regioisomer analogous to 31 and 33 was also obtained.

This reaction was conducted with 2.0 equiv ArBr, 10 mol % Pd(OAc)2 and 15 mol % (±)-BINAP.

This reaction proceeded to 94% conversion.

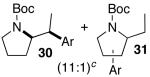

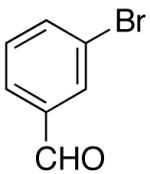

Yields in the transformations of (E)-alkene 25 were generally modest, although diastereoselectivities were uniformly high (>20:1 dr). Relatively long reaction times were required for these transformations (27–44 h), and in some instances (entries 2–3) the formation of ca. 10–20% of regioisomeric side products (31, 33)17 was also observed. Electron-poor aryl bromides could be employed as coupling partners, but use of electron-rich aryl bromides, such as 4-bromoanisole, led to low conversions (<50%) and formation of large amounts of side-products resulting from competing Heck arylation of the alkene. Reactions of Cbz-protected (E)-alkene substrate 27 proceeded in modest yield, but with excellent (≥20:1) regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity (entries 4–5).

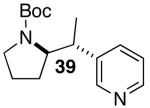

Palladium-catalyzed carboamination reactions of (Z)-alkene substrates 28 and 29 also afforded products resulting from suprafacial addition to the alkene with >20:1 dr and moderate chemical yield (Table 4, entries 6–11). However, several significant differences in reactivity between (E)- and (Z)-alkene substrates were observed. The reactions of 28 and 29 were usually faster than transformations of (E)-alkene substrates 25 and 27. In addition, the regioselectivity in reactions of 28 and 29 with m- and p-substituted aryl bromides was uniformly high (>20:1). For example, the coupling of 25 with methyl 4-bromobenzoate required 44 h and afforded a 5:1 mixture of regioisomers 32 and 33 (entry 3), whereas the analogous reaction of 28 was complete in 21 h, and afforded a single pyrrolidine product (entry 7, 37).

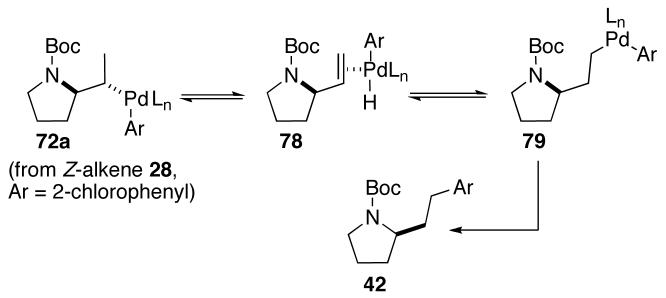

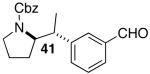

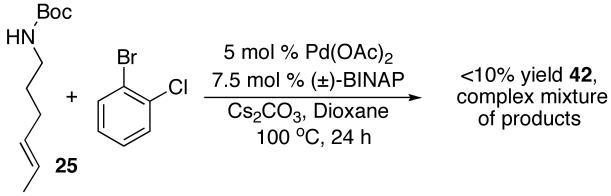

A final difference in the reactivity of (E)- vs. (Z)-alkenes was observed when we attempted to couple 25 and 28 with 2-bromochlorobenzene (eq 3-4). Surprisingly, the reaction of this aryl halide with (Z)-alkene 28 failed to provide the expected 2-(sec-phenethyl)pyrrolidine product, but instead afforded regioisomer 42 in 70% yield (eq 3).18 In contrast, the analogous reaction of N-protected (E)-alkene substrate 25 with 2-bromochlorobenzene gave a complex mixture of products. This mixture contained less than 10% of 42, and little or none of the expected 2-(sec-phenethyl)pyrrolidine (eq 4).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

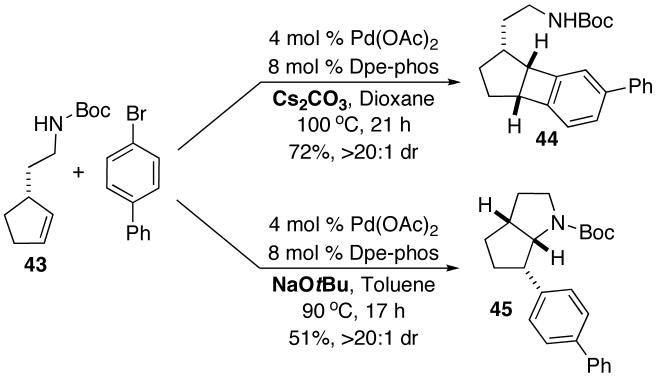

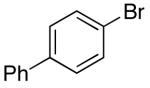

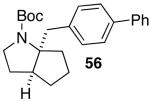

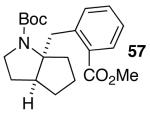

Attempts to couple cyclopentene-derived substrate 43 with 4-bromobiphenyl under the optimized mild reaction conditions also led to surprising results.19 As shown in eq 5, this transformation afforded less than 5% of the expected product 45. Instead, benzocyclobutene 44 was generated in 72% yield and >20:1 dr.20 In contrast, when the strong base NaOtBu was employed for this transformation the expected N-Boc-6-aryl octahydrocyclopenta[b]pyrrole 45 was formed in 51% yield with >20:1 dr (eq 6).

|

(5) | (6) |

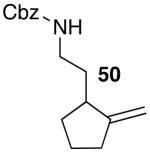

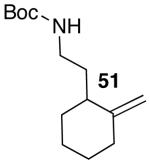

Reactions of 4-Substituted Pent-4-enylamine Derivatives

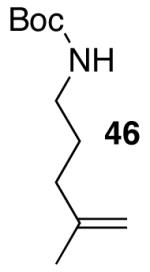

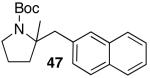

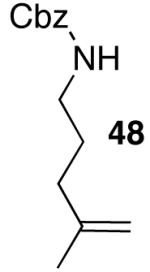

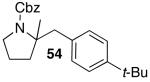

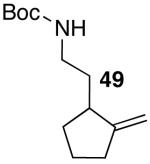

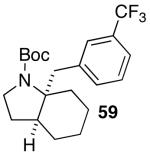

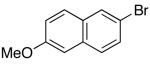

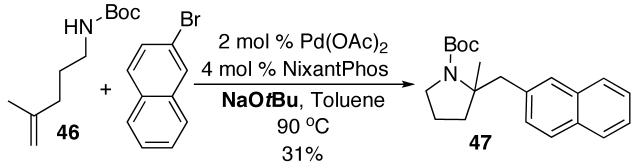

N-protected γ-aminoalkenes bearing substituents at the 4-position are another class of compounds that are not suitable substrates for Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions conducted under strongly-basic conditions. For example, the conversion of 46 to 47 proceeded in only 31% yield when NaOtBu was employed as base (eq 7). Fortunately, use of the mild reaction conditions described above (Cs2CO3, dioxane) with catalysts supported by Nixantphos10,21 provided excellent results with these substrates. These new conditions facilitated the preparation of 47 in 73% yield (Table 5, entry 1).

Table 5.

Palladium-Catalyzed Carboamination of 4-Substituted Pent-4- enylamine Derivativesaa

| Entry | Amine | Aryl bromide | Product | Rxn. Time (h) |

Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

|

19 | 73 |

| 2 | 46 |  |

|

18 | 75 c |

| 3 | 46 |  |

|

36 | 66 |

| 4 |  |

|

|

19 | 71 |

| 5 | 48 |  |

|

20 | 61 |

| 6 |  |

|

|

25 | 83 |

| 7 | 46 |  |

|

42 | 69 d |

| 8 |  |

|

|

20 | 75 |

| 9 |  |

|

|

7 | 72 |

| 10 | 51 |  |

|

7 | 78 |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv amine, 1.2 equiv ArBr, 2.3 equiv Cs2CO3, 2 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 4 mol % Nixantphos, dioxane (0.25 M), 100 °C.

Yield refers to average isolated yield obtained in two or more experiments. Products 56–60 with two stereocenters were obtained with >20:1 dr.

This reaction was conducted with 4 mol % Pd(OAc)2 and 8 mol % Nixantphos.

This reaction was conducted with 5 mol % Pd(OAc)2, and 10 mol % Nixantphos and proceeded to 80% conversion.

|

(7) |

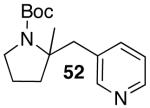

As shown in Table 5, various aryl bromides were effectively coupled with 46 and the Cbz-protected analog 48, including electron-poor, electron-rich and heteroaryl derivatives (entries 1–5). The 4-substituted pent-4-enylamine derivatives are more reactive than the N-protected hex-4-enylamines, and in most cases carboaminations of 46 and 48 can be effectively achieved using only 2 mol % Pd, compared to the higher catalyst loadings (5–10 mol % Pd) that are required for (E)- or (Z)-alkene substrates 25 and 27-29.

These conditions are also effective for the coupling of methylene cyclopentane and -cyclohexane derivatives 49–51 with several different aryl bromides. Reactions of these substrates provided fused bicyclic products 56–60 in good yield with >20:1 diastereoselectivity (Table 5, entries 6–10).

Attempted Reactions of Trisubstituted Alkene Derivatives

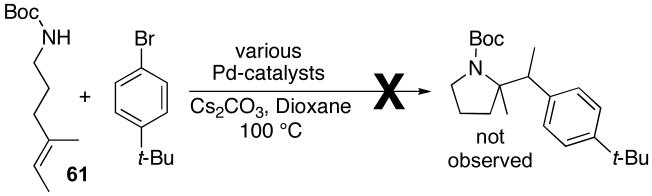

In order to further test the degree of alkene substitution tolerated in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions, we briefly examined reactions of trisubstituted alkenes 61 and 62 (eq 8-9). Unfortunately, neither of these substrates was converted to the desired pyrrolidine product. Reactions of 61 provided mainly products resulting from Heck arylation of the alkene, whereas no reaction was observed between substrate 62 and 4-bromo-tert-butylbenzene at temperatures up to 175 °C with several different catalyst systems.

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

Deuterium Labeling Experiments

In our previous investigations on Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions that employ NaOtBu as base, we determined that transformations of cyclopent-2-enylethylamine-derived substrates (e.g. 43) afford products resulting from suprafacial addition to the alkene (eq 6).5a,c,d,22 This proved to be a key piece of data that suggested the carboaminations proceed via a mechanism involving a rare syn-aminopalladation process (see below). However, prior to the studies described in this Article, we had not elucidated the stereochemistry of alkene addition in reactions using the weak base Cs2CO3,23 nor had alkene addition stereochemistry been examined with terminal alkene substrates. Moreover, although reactions of terminal alkenes provide pyrrolidine products regardless of whether NaOtBu or Cs2CO3 is used as base, transformations of cyclopent-2-enylethylamine derivative 43 provide much different products depending on the nature of the base (eq. 5-6). Thus, two significant questions about the mechanism of Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions remained unresolved: a) do reactions of internal alkenes, terminal alkenes, and cycloalkenes all proceed via a similar mechanism? b) do reactions that employ Cs2CO3 as base occur through a pathway that is mechanistically analogous to reactions in which NaOtBu is used?

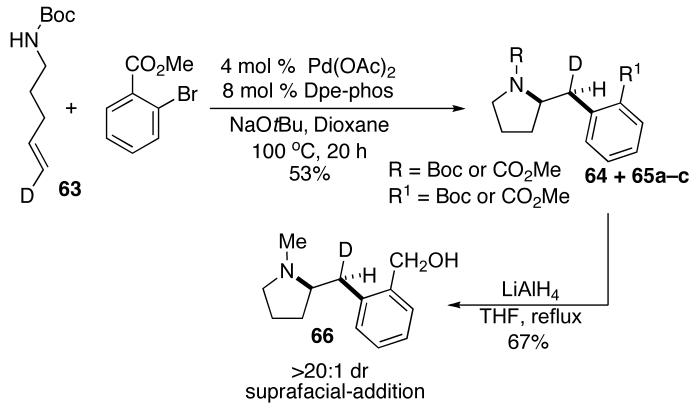

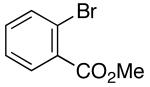

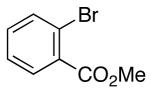

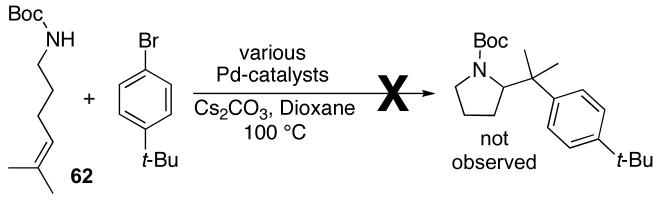

The results shown above in Table 4 and equation 2 indicate that transformations of acyclic 1,2-disubstituted alkene substrates occur with suprafacial addition using either NaOtBu or Cs2CO3 as base, and are stereospecific. In order to address questions about the mechanism of carboamination reactions of terminal alkenes, we prepared a simple terminal alkene substrate 63 bearing a deuterium label at C5. As shown below (eq 10), treatment of 63 with methyl 2-bromobenzoate24 in the presence of Cs2CO3 and the Pd(OAc)2/Dpe-phos catalyst afforded 64 in 72% yield as a single stereoisomer that results from suprafacial addition to the alkene. No side products resulting from loss or migration of deuterium were observed.

|

(10) |

To determine if the nature of the base had an effect on the stereochemistry of addition, the reaction of 63 with methyl 2-bromobenzoate was also conducted using NaOtBu as base. In addition to the expected product 64, this transformation provided three additional products 65a–c that result from scrambling of the alkoxide groups on the carbamate and ester appendages (Scheme 1). Fortunately, treatment of this mixture with LiAlH4 afforded a single product stereoisomer 66 that derives from suprafacial alkene addition in the carboamination reaction.

scheme 1.

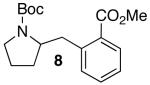

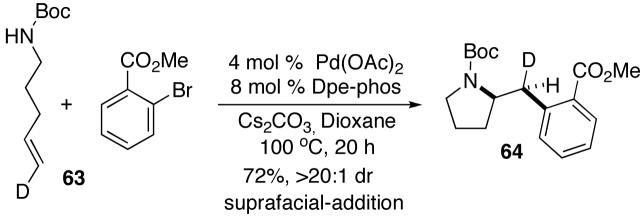

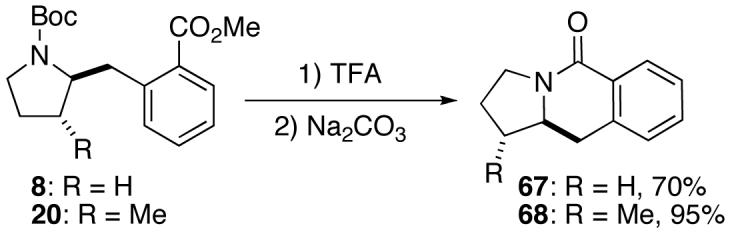

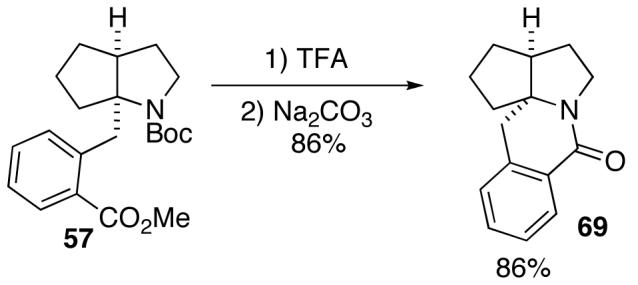

Conversion of Pyrrolidine Products to Tetrahydropyrroloisoquinolin-5-ones

In addition to significantly expanding the scope of pyrrolidine-forming reactions, the mild reaction conditions described above can be used in a high-yielding three-step reaction sequence for the conversion of N-Boc-protected γ-aminoalkenes to substituted tetrahydropyrroloisoquinolin-5-ones. As shown below (eq 11-12), N-Boc pyrrolidine derivatives 8, 20, and 57, which were prepared from 1, 14, and 49 (Table 2, entry 5; Table 3, entry 3, and Table 5, entry 7), were transformed to 67–69 in good to excellent yields via treatment with TFA followed by Na2CO3. These heterocyclic scaffolds are displayed in several biologically active natural products and pharmaceutical leads.25

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

Discussion

Synthetic Scope and Limitations

Palladium-catalyzed carboamination reactions of aryl bromides with γ-aminoalkenes bearing N-acyl, N-Boc, or N-Cbz protecting groups are mild and efficient means for the stereoselective synthesis of functionalized pyrrolidines. Although the scope of these transformations is somewhat limited when the strong base NaOtBu is employed as a key reagent,5c the new reaction conditions described in this Article,9 which replace NaOtBu with Cs2CO3, are effective with a much broader range of substrates. A number of functional groups are tolerated under these conditions, including methyl esters, alkyl acetates, enolizable ketones, and nitro groups. In addition, the reactions can also be conducted with aryl bromides that are electron-neutral, electron-poor, or heteroaromatic. Electron-rich aryl bromides can be effectively coupled with pent-4-enylamine derived substrates, although reactions of these electrophiles with hex-4-enylamine derivatives are slow and generally fail to proceed beyond 50% conversion even with relatively high catalyst loadings (10 mol % Pd). Aryl bromides bearing substituents in the meta- or para-positions provided good results with all N-protected-γ-aminoalkenes examined in these studies, and ortho-substituted derivatives can be coupled with several different N-protected pent-4-enylamines. In addition, the use of methyl 2-bromobenzoate as the aryl halide electrophile leads to the formation of 2-benzylpyrrolidine derivatives that can be converted to substituted tetrahydropyrroloisoquinolin-5-ones in good yield through a two step sequence of Boc-deprotection followed by intramolecular amide bond formation (eq 11-12). However, carboamination reactions of o-substituted aryl bromides with hex-4-enylamine derivatives were generally not effective, except for the conversion of (Z)-alkene 28 and 2-bromochlorobenzene to 2-(1-phenylethyl)pyrrolidine 42 (eq 3). Efforts to couple alkenyl bromide electrophiles were also unsuccessful, although alkenyl bromides can be used in carboamination reactions of terminal alkene substrates when NaOtBu is employed as base.5c

The mild reaction conditions described in this Article also broaden the scope of Pd-catalyzed carboaminations with respect to the degree of alkene substitution that is tolerated. Transformations that use NaOtBu as base are generally limited to terminal alkenes, but moderate yields can be obtained with the cycloalkene substrate N-Boc-cyclopent-2-enylethylamine (43). In contrast, the use of Cs2CO3 allows for coupling reactions of substrates bearing either pendant terminal alkenes or disubstituted alkenes. However, substrate 43 is converted to benzocyclobutene derivatives under these conditions, rather than to substituted pyrrolidines.19 In addition, reactions of very sterically encumbered trisubstituted alkenes failed to generate pyrrolidine products. It appears likely that the development or discovery of new catalyst systems will be required in order to effect carboamination of these compounds. When Cs2CO3 is employed as base, the relative reactivity of different alkenes decreases in the order of: terminal alkenes > 1,1-disubstituted alkenes > (Z)-1,2-disubstituted alkenes > (E)-1,2-disubstituted alkenes >>> trisubstituted alkenes. This order of reactivity mirrors that of many metal-catalyzed transformations that involve alkene insertion processes.26

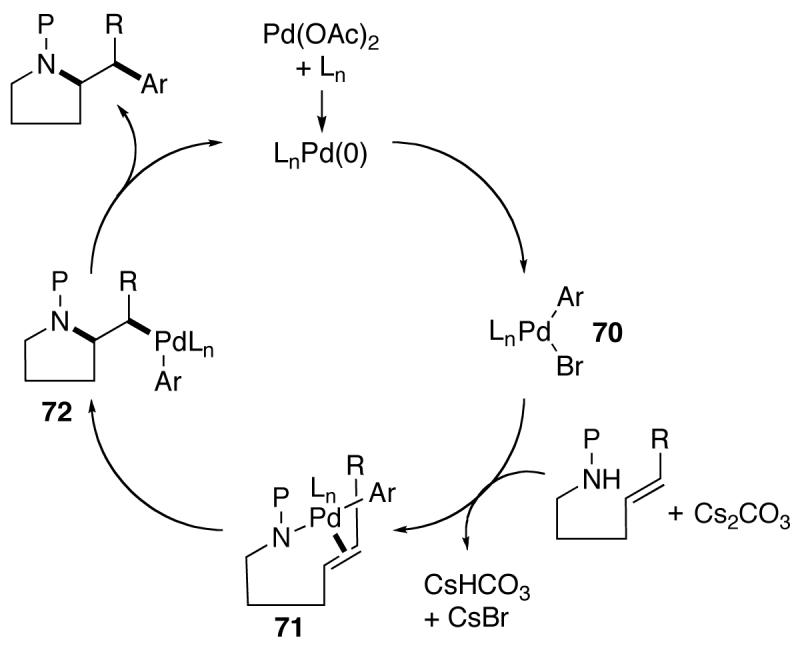

Reaction Mechanism and Origin of Regioisomers

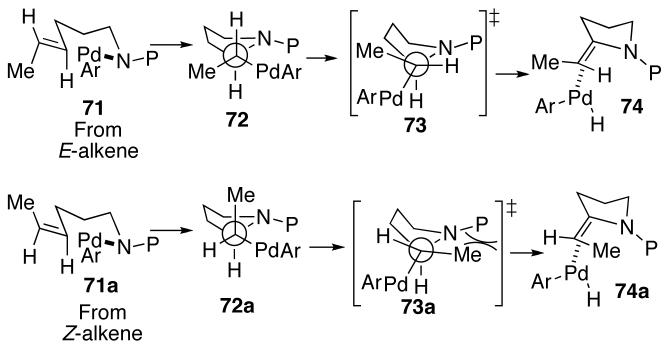

The pyrrolidine-forming carboamination reactions between N-protected-γ-aminoalkenes and aryl bromides appear to be mechanistically similar to other Pd-catalyzed carboetherification and carboamination reactions that afford oxygen-22,27 or nitrogen5 heterocycles. A simplified catalytic cycle for the pyrrolidine-forming reactions is shown below (Scheme 2). The transformations are presumably initiated by oxidative addition of the aryl bromide to a Pd(0) catalyst that is generated in situ from the combination of Pd(OAc)2 and phosphine ligand. The resulting LnPd(Ar)(Br) intermediate 70 is likely converted to palladium(aryl)(amido) complex 71 through reaction with the amine substrate and base.12 Intramolecular syn-aminopalladation of 71 can provide 72,5,28,29 which is transformed to the observed product via C–C bond-forming reductive elimination.30

Scheme 2.

Catalytic cycle.

Two key pieces of evidence support this mechanistic hypothesis, along with the notion that the mechanism for pyrrolidine formation is not dependent on the nature of the base.31 First of all, the transformations proceed with suprafacial addition across both terminal and internal alkenes, as illustrated by the examples shown in Table 4, equations 2, 6, and 10, and Scheme 1. The suprafacial addition is observed when either NaOtBu or Cs2CO3 is employed as base, and is consistent with the conversion of 71 to 72 via syn-aminopalladation.

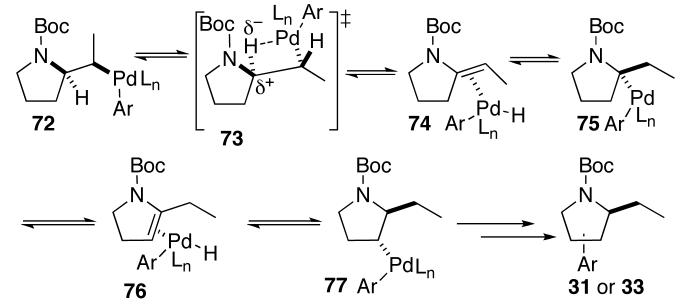

The formation of 2-ethylpyrrolidine derivatives 31 and 33 (Table 4, entries 2–3) and 2-(1-phenylethyl)pyrrolidine 42 (eq 3) is also consistent with the mechanism shown above, and cannot satisfactorily be explained by alternative mechanisms that involve carbopalladation rather than aminopalladation.32 As shown below (Scheme 3), products 31 and 33 are most likely generated through syn-β-hydride elimination from intermediate 72 (via transition state 73) to give 74. Reinsertion of the alkene into the Pd-H bond of 74 with the opposite regioselectivity would yield 75, which can undergo a second series of β-hydride elimination/reinsertion processes to provide 77. Reductive elimination from 77 could then afford isomers arylated at the 3-position, whereas additional β-hydride elimination/reinsertion steps could ultimately generate isomers arylated at the 4- or 5-position.

Scheme 3.

Formation of 31 and 33

The formation of 3-arylpyrrolidine side products is commonly observed in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of γ-(N-arylamino) alkenes bearing relatively electron-rich N-aryl groups (e.g. Ph or PMP).5a In contrast, the formation of mixtures of regioisomers is usually not observed in reactions of N-Boc, N-acyl, or N-Cbz protected substrates, except for couplings of (E)-disubstituted alkenes 25 and 27 with electron-poor aryl bromides (Table 4, entries 2–3). The absence of these side-products in most reactions of N-Boc and N-acyl protected substrates may be due to decreased rates of β–hydride elimination from intermediate 72 relative to the analogous N-aryl derivative. This may be due to stabilization of 72 through chelation of the metal to the carbonyl of the amide or carbamate,33 or through inductive effects induced by the amide/carbamate protecting groups. These electron-withdrawing groups likely destabilize the developing positive charge on C2 in the transition state for β-hydride elimination (73).34 The fact that a similar regioisomer was not generated when the electron-neutral 2-bromonaphthalene was coupled with 25 may be due to the decreased electrophilicity of the arylpalladium complex (72, Ar = 2-naphthyl), which could slow the rate of β-hydride elimination. However, the reasons for formation of only trace amounts (ca. 1–5%) of regioisomers in transformations of Cbz-protected substrate 27 are unclear.

The pathway by which 42 is generated is likely similar to the mechanism for the formation of 31 and 33, but with initial β-elimination of a hydride from the methyl group of 72a (Scheme 4) rather than from C2 (Scheme 3). The formation of regioisomers analogous to 42 was not observed with p- or m-substituted aryl bromides. This suggests the steric bulk of 2-bromochlorobenzene may increase the rate of β-hydride elimination from the less hindered methyl group relative to the more hindered C2 position, or slow the rate of reductive elimination from 72a or 77 relative to 79.35

Scheme 4.

Formation of 42

Interestingly, the formation of regioisomers similar to 31 and 33 was not observed in reactions of N-Boc-protected (Z)-alkene substrate 28. This may be due to severe developing allylic strain interactions in the transition state for β-hydride elimination, from steric destabilization of the resulting (Ar)Pd(H)(alkene) complex, or both. As shown in Scheme 5, alkene insertion from 71 would yield 72, which could undergo β-hydride elimination from transition state 73 to provide 74. This intermediate could then be converted to the observed regioisomers as described above. A similar sequence of transformations from (Z)-alkene-derived intermediate 71a could lead to the analogous intermediate 74a. However, the eclipsing interaction between the methyl group and the carbamate protecting group in transition state 73a would result in developing allylic strain similar to that in an S-cis-locked-(Z),(Z)-1,4-diene. This presumably raises the energy of the transition state to a sufficient degree such that competing β-elimination of the C2-hydrogen atom is minimized. Further evidence for the high energy of transition state 73a comes from the formation of regioisomer 42 in the reaction of (Z)-alkene 28 with 2-bromochlorobenzene (eq 3). This product results from β-hydride elimination of 72a from the less electronically favorable methyl-position.36

Scheme 5.

Ligand Effects

Three ligands that were surveyed in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions that use Cs2CO3 as a base were found to provide good results with the majority of substrate combinations described in this paper. In most cases, Dpe-phos provided satisfactory yields in transformations of 1- or 3-substituted pent-4-enylamine derivatives. However, more sterically encumbered 4-substituted substrates were converted to pyrrolidine products most efficiently when Nixantphos was employed as ligand. Finally, highest yields in carboaminations of hex-4-enylamine derivatives were usually obtained with (±)-BINAP.

The precise origin of the observed ligand effects is not clear, but is likely influenced by the effect of ligand bite angle on the relative rates of carboamination vs. competing Heck arylation or N-arylation of the substrate. In general, use of Nixantphos led to greater amounts of N-arylated side products than Dpe-phos or BINAP, whereas the latter two ligands led to greater amounts of products resulting from Heck arylation. The relatively wide bite angle37 of Nixantphos (>108°)38 compared to Dpe-phos (104°) and BINAP (93°) may accelerate the aminopalladation step (71 to 72) as well as competing C–N bond-forming reductive elimination from 71;39 the change in relative rates appears to depend on substrate structure. However, the electronic properties of the ligand are also likely of importance, as the related wide-bite angle ligand Xantphos (108°)37 was inferior to both Nixantphos and Dpe-phos, and provided large amounts of N-arylated side products.

Stereochemistry

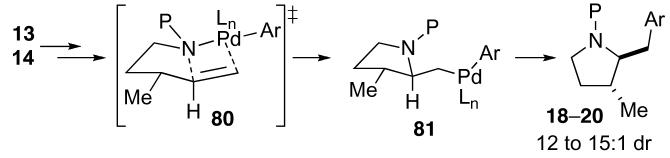

The stereochemistry of pyrrolidine products generated in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions of N-protected γ-aminoalkenes appears to be determined in the syn-aminopalladation step of the catalytic cycle illustrated above (Scheme 2, 71 to 72). The syn-aminopalladation ultimately leads to suprafacial addition of the nitrogen atom and the aromatic group across the substrate C–C double bond. Moreover, it appears likely that the alkene insertion proceeds through a highly organized cyclic transition state, in which the alkene π-system is eclipsed with the Pd–N bond,40 and substituents on the tether between the amine and the alkene are oriented to minimize nonbonding interactions. For example, transformations of substrates 13–14 bearing allylic substituents provide trans-2,3-disubstituted pyrrolidine products 18–20 (Table 3, entries 1–3). As shown below (Scheme 6), syn-aminopalladation via 80, in which the C3-methyl group is oriented in a pseudoequatorial position, would provide the observed major diastereomers.

Scheme 6.

Stereochemistry of 18–20

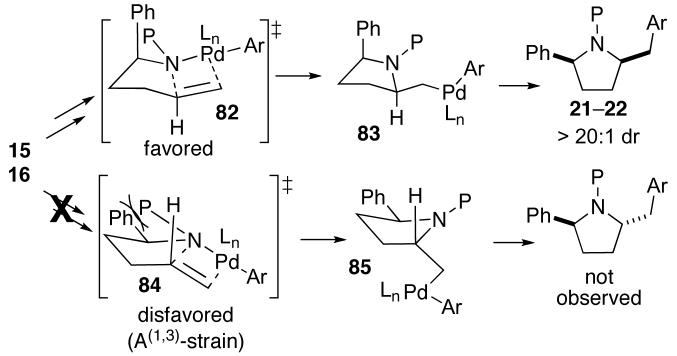

The conversion of substrates 15–16 to cis-2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines 21–22 can be rationalized through a similar transition state model. As shown in Scheme 7, syn-aminopalladation via transition state 82 would generate 83, which can be converted to the observed products through reductive elimination. Cyclization through 82, in which the C1-phenyl group is oriented in a pseudoaxial position appears to be favored over transition state 84, which suffers from A(1,3)-strain between the C1-phenyl group and the nitrogen protecting group.41,42

Scheme 7.

Stereochemistry of 21–22

Summary and Conclusion

In conclusion, the mild reaction conditions described in this Article greatly expand the scope of Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination chemistry. The combined use of the weak base Cs2CO3, dioxane solvent, Pd(OAc)2 precatalyst, and the appropriate phosphine ligand allows for the stereoselective synthesis of substituted pyrrolidines from N-protected γ-aminoalkenes with good tolerance of functional groups. The pyrrolidine products are formed in moderate to excellent yields, with diastereoselectivities ranging from 12 to >20:1. The mild conditions also greatly increase tolerance of alkene substitution, and for the first time substrates bearing acyclic disubstituted alkenes can be successfully employed in these reactions.

The observed selectivity for suprafacial addition with both internal and terminal alkene substrates provides additional evidence in support of our proposed reaction mechanism, which involves intramolecular syn-aminopalladation as a key step. In addition, the results described above suggest this mechanism of pyrrolidine-formation is operational regardless of the degree of alkene substitution, and with either Cs2CO3 or NaOtBu as the stoichiometric base.

Future studies will be directed towards the development/discovery of highly active catalysts that can transform tri- and tetrasubstituted alkene derivatives, along with additional applications of these transformation to the synthesis of biologically active molecules.

Experimental

General Procedure for Pd-Catalyzed Carboamination Reactions of Aryl Bromides

A flame-dried Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirbar was cooled under a stream of nitrogen and charged with the aryl bromide (1.2 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (2 mol %), Dpe-phos, dppe, (±)–BINAP, or Nixantphos (4 mol%) and Cs2CO3 (2.3 equiv). The tube was purged with nitrogen and a solution of the N-protected amine substrate (1.0 equiv) in dioxane (5 mL/mmol substrate) was then added. The resulting mixture was heated to 100 °C with stirring until the starting material had been consumed as determined by GC analysis. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and saturated aq NH4Cl (1 mL) and ethyl acetate (1 mL) were added. The layers were separated, the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was then purified by flash chromatography on silica gel.

2-(4-tert-Butylbenzyl)pyrrolidine-1-carboxylic acid tert-butyl ester (2).

The general procedure was employed for the reaction of 4-tert-butyl bromobenzene (52 μL, 0.30 mmol) with 1 (47 mg, 0.25 mmol) using Dpe-phos as ligand. This procedure afforded 66 mg (83%) of the title compound as a pale yellow oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ7.38–7.26 (m, 2 H), 7.22–7.07 (m, 2 H), 4.12–3.84 (m, 1 H), 3.49–3.23 (m, 2 H), 3.23–2.96 (m, 1 H), 2.60–2.42 (m, 1 H), 1.92–1.67 (m, 4 H), 1.52 (s, 9 H), 1.32 (s, 9 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ154.5, 148.9, 136.1, 129.1, 125.2, 79.0, 58.8, 46.4, 40.0, 34.3, 31.4, 29.7, 28.6, 22.7; IR (film) 1695 cm−1. Anal calcd for C20H31NO2: C, 75.67; H, 9.84; N, 4.41. Found: C, 75.46; H, 9.88; N, 4.38.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the NIH-NIGMS (GM 071650) for financial support of this work. MBB was supported by a Bristol-Myers Squibb Award in Synthetic Organic Chemistry. Additional funding for these studies was provided by the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation (New Faculty Award, Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar Award), Research Corporation (Innovation Award), Eli Lilly, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and 3M.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, spectroscopic data, descriptions of stereochemical assignments, and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds reported in the text (146 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.For recent reviews, see: Bellina F, Rossi R. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7213–7256. Hackling AE, Stark H. Chem. BioChem. 2002;3:946–961. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021004)3:10<946::AID-CBIC946>3.0.CO;2-5. Lewis JR. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:95–128. doi: 10.1039/a909077k.

- 2.For recent reviews, see: Coldham I, Hufton R. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2765–2810. doi: 10.1021/cr040004c. Pyne SG, Davis AS, Gates NJ, Hartley JP, Lindsay KB, Machan T, Tang M. Synlett. 2004:2670–2680. Felpin F–X, Lebreton J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:3693–3712. Pichon M, Figadere B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:927–964.

- 3.For examples of Cu-catalyzed intramolecular carboamination of N-(arylsulfonyl)-2-allylanilines and related derivatives, see: Sherman ES, Fuller PH, Kasi D, Chemler SR. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3896–3905. doi: 10.1021/jo070321u. Sherman ES, Chemler SR, Tan TB, Gerlits O. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1573–1575. doi: 10.1021/ol049702+. For Pd(II)-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of alkenes bearing tethered nitrogen nucleophiles, see: Harayama H, Abe A, Sakado T, Kimura M, Fugami K, Tanaka S, Tamaru Y. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:2113–2122. doi: 10.1021/jo961988b. For carboamination reactions between alkenes and N-allylsulfonamides, see: Scarborough CC, Stahl SS. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3251–3254. doi: 10.1021/ol061057e. For carboamination of vinylcyclopropanes, see: Larock RC, Yum EK. Synlett. 1990:529–530. For 1,1-carboamination of alkenes, see: Harris GD, Jr., Herr RJ, Weinreb SM. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2528–2530. Harris GD, Jr., Herr RJ, Weinreb SM. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5452–5464. Larock RC, Yang H, Weinreb SM, Herr RJ. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:4172–4178.

- 4.For reviews, see: Wolfe JP. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:571–582. Wolfe JP. Synlett. 2008 accepted for publication.

- 5.(a) Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:3605–3608. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lira R, Wolfe JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13906–13907. doi: 10.1021/ja0460920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6447–6459. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ney JE, Wolfe JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8644–8651. doi: 10.1021/ja0430346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang Q, Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2575–2578. doi: 10.1021/ol050647u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ney JE, Hay MB, Yang Q, Wolfe JP. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1614–1620. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200505172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2353–2356. doi: 10.1021/ol0606435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For closely related approaches to the synthesis of piperazines, imidazolidin-2-ones, and isoxazolidines via Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions, see: Nakhla JS, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3279–3282. doi: 10.1021/ol071241f. Fritz JA, Nakhla JS, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2531–2534. doi: 10.1021/ol060707b. Fritz JA, Wolfe JP. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6838–6852. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.015. Peng J, Jiang D, Lin W, Chen Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:1391–1396. doi: 10.1039/b701509g. Peng J, Lin W, Yuan S, Chen Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3145–3148. doi: 10.1021/jo0625958. Dongol KG, Tay BY. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:927–930.

- 7.Secondary carbamates decompose to afford reactive isocyanates when heated in the presence of NaOtBu. See: Tom NJ, Simon WM, Frost HN, Ewing M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:905–906.

- 8.The only substrates of this type that have been effectively employed in Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions are N-protected cyclopent-2-enylethylamine derivatives. See references 5a, 5c, and 5d.

- 9.A portion of these studies have been previously communicated. See: Bertrand MB, Leathen ML, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2007;9:457–460. doi: 10.1021/ol062808f.

-

10.Dpe-phos = bis(2-diphenylphosphinophenyl)ether. Xantphos = 9,9-dimethyl-4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)xanthene. Nixantphos = 4,6-bis (diphenylphosphino)phenoxazine. BINAP = 2,2′-diphenylphosphino-1,1′-binaphthyl. Dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane.

- 11.In most instances the use of other bases led to very slow consumption of starting material and/or competing Heck arylation of the alkene moiety.

- 12.The use of Cs2CO3 and other weak bases in Pd-catalyzed N-arylation reactions of amines with aryl halides has been reported. For reviews, see: Muci AR, Buchwald SL. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002;219:131–209. Hartwig JF. In: Modern Arene Chemistry. Astruc D, editor. Wiley, VCH; Weinheim: 2002. pp. 107–168. Schlummer B, Scholz U. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1599–1626.

- 13.In some cases use of DME as solvent provided comparable results to those obtained with dioxane (see Table 2, entries 3, 4, 7, and 9).

- 14.See the Supporting Information for details on the assignment of product stereochemistry.

- 15.Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Unpublished results.

- 16.Use of Nixantphos as the ligand for this transformation resulted in the formation of 26 in 22% yield with >20:1 dr.

- 17.We have been unable to separate these regioisomers from the major product. The structures of 31 and 33 have been assigned based on analysis of EI-MS fragmentation patterns and the observation of a triplet (assigned as the CH3 signal from the 2-ethyl group) at ∼0.9 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture. Similar products have been observed in analogous reactions that generate N-aryl pyrrolidines. See reference 5a.

- 18.This product contained ca. 8% of an unidentified impurity.

- 19.These results have been previously communicated. See: Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3073–3075. doi: 10.1021/ol071120f.

- 20.This transformation is effective with a number of different aryl bromides. See reference 19.

- 21.Use of Dpe-phos as the ligand for this reaction afforded 47 in 43% isolated yield.

- 22.For related studies on the mechanism of Pd-catalyzed carboetherification reactions of γ-hydroxyalkenes that generate tetrahydrofuran products, see: Hay MB, Wolfe JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16468–16476. doi: 10.1021/ja054754v.

- 23.The isolation of 5- and 6-aryl N-Boc-octahydrocyclopenta[b]pyrrole side products in the conversion of 43 to benzocyclobutene derivatives when certain aryl halides were employed was consistent with this mechanism. However, the formation of these side products was only observed in two cases. See reference 19.

- 24.This aryl bromide was chosen to facilitate elucidation of product stereochemistry. This was achieved by conversion of 64 to a tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative through treatment with TFA followed by Na2CO3. See the Supporting Information for complete details.

- 25.(a) Yang C–W, Chuang T–H, Wu P–L, Huang W–H, Lee S–J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2007;354:942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chuang T–H, Lee S–J, Yang C–W, Wu P–L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;5:860–867. doi: 10.1039/b516152e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Aboul-Ela MA, El-Lakany AM, Hammoda HM. Pharmazie. 2004;59:894–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zuccotto F, Zvelebil M, Brun R, Chowdhury SF, Di Lucrezia R, Leal I, Maes L, Ruiz-Perez LM, Gonzalez Pacanowska D, Gilbert IH. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2001;36:395–405. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(01)01235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Heck RF. Org. React. 1982;27:345–390. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brase S, de Meijere A. In: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Diederich F, Stang PJ, editors. Wiley VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 1998. Ch. 3. [Google Scholar]; (c) Link JT. Org. React. 2002;60:157–534. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Wolfe JP, Rossi MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1620–1621. doi: 10.1021/ja0394838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hay MB, Hardin AR, Wolfe JP. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3099–3107. doi: 10.1021/jo050022+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For examples of syn-alkene insertion into Pt-N bonds, see: Cowan RL, Trogler WC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4750–4761. Cowan RL, Trogler WC. Organometallics. 1987;6:2451–2453. For examples of syn-alkene insertion into Ni-N bonds, see: VanderLende DD, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:5319–5326. For examples of syn-alkene insertion into Ir-N bonds, see: Casalnuovo AL, Calabrese JC, Milstein D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:6738–6744. For examples of syn-alkene insertion into Rh-N bonds, see: Zhao P, Krug C, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12066–12073. doi: 10.1021/ja052473h. For examples of syn-insertion of dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate into Pd-N bonds, see: Villanueva LA, Abboud KA, Boncella JM. Organometallics. 1992;11:2963–2965. Minatti A, Muniz K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1142–1152. doi: 10.1039/b607474j.

- 29.For other Pd-catalyzed reactions that likely proceed via alkene syn-aminopalladation, see: Helaja J, Gottlich R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 2002:720–721. doi: 10.1039/b201209j. Tsutsui H, Narasaka K. Chem. Lett. 1999:45–46. Brice JL, Harang JE, Timokhin VI, Anastasi NR, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2868–2869. doi: 10.1021/ja0433020.

- 30.Milstein D, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:4981–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The formation of benzocyclobutene 44 from the Pd-catalyzed reaction of 43 with 4-bromobiphenyl when Cs2CO3 is used as a base appears to arise from a divergence in mechanism prior to formation of intermediate palladium amido complex 71. For further discussion, see reference 19.

- 32.For a detailed discussion of all mechanistic possibilities in Pd-catalyzed reactions of unsaturated amines or alcohols that generate heterocyclic products, see reference 4b.

- 33.(a) Zhang L, Zetterberg K. Organometallics. 1991;10:3806–3813. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee C-W, Oh KS, Kim KS, Ahn KH. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1213–1216. doi: 10.1021/ol0056426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Oestreich M, Dennison PR, Kodanko JJ, Overman LE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:1439–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Clique B, Fabritius C-H, Couturier C, Monteiro N, Balme G. Chem. Commun. 2003:272–273. doi: 10.1039/b211856b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mueller JA, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7005–7013. doi: 10.1021/ja034262n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.It is also possible that the o-chloro substituent facilitates β-hydride elimination by effecting dissociation of one arm of the chelating phosphine ligand. For a discussion of the effect of o-halo groups on ligand substitution processes, see: Kuniyasu H, Yamashita F, Terao J, Kambe N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5929–5933. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604986.

- 36.The transition state for β-hydride elimination from the methyl group would contain a developing partial positive charge on a primary carbon atom.

- 37.(a) Ozawa F, Kubo A, Matsumoto Y, Hayashi T, Nishioka E, Yanagi K, Moriguchi K. Organometallics. 1993;12:4188–4196. [Google Scholar]; (h) van Haaren RJ, Goubitz K, Fraanje J, van Strijdonck GPF, Oevering H, Coussens B, Reek JNH, Kamer PCJ, van Leeuwen PWNM. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:3363–3372. doi: 10.1021/ic0009167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The bite angle of flexible ligands is dependent on coordination environment. No x-ray structures of (Nixantphos)PdX2 complexes have been reported, thus we cannot provide a precise value for the Nixantphos bite angle for comparison to the bite angles of Xantphos, Dpe-Phos, and BINAP, which were obtained from x-ray structures of their PdX2 complexes. However, the metal-independent calculated natural bite angle of Nixantphos is 114°, whereas that of Xantphos is 111°. Thus, we feel it is reasonable to estimate that the bite angle of (Nixantphos)PdX2 should exceed that of the analogous Xantphos complex.

- 39.Xantphos has previously been demonstrated to provide good results in Pd-catalyzed N-arylation reactions of amides and carbamates. See: Yin J, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6043–6048. doi: 10.1021/ja012610k.

- 40.Related alkene carbopalladation processes that occur in intramolecular Heck reactions are believed to proceed through similar transition states. Other possible transition states in which the alkene is perpendicular to the M-C bond appear to be significantly higher in energy. See: Overman LE. Pure. Appl. Chem. 1994;66:1423–1431. and references cited therein.

- 41.For further discussion of A(1,3)-strain in transformations involving N-substituted amines, see: Hoffmann RW. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1841–1860. Hart DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:397–398. Williams RM, Sinclair PJ, Zhai D, Chen D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1547–1557. Kano S, Yokomatsu T, Iwasawa H, Shibuya S. Heterocycles. 1987;26:2805–2809.

- 42.The conversion of 17 to 23 and 24 also occurs through a transition state in which the C-1 substituent (C9H19) is pseudoaxial. For further discussion of this transformation in the context of a total synthesis of (+)-preussin, see reference 5g.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.