Abstract

Emerging evidence has indicated a regulatory role of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) in synaptic plasticity as well as in higher brain functions, such as learning and memory. However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the actions of Cdk5 at synapses remain unclear. Recent findings demonstrate that Cdk5 regulates dendritic spine morphogenesis through modulating actin dynamics. Ephexin1 and WAVE-1, two important regulators of the actin cytoskeleton, have both been recently identified as substrates for Cdk5. Importantly, phosphorylation of these proteins by Cdk5 leads to dendritic spine loss, revealing a potential mechanism by which Cdk5 regulates synapse remodeling. Furthermore, Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of ephexin1 is required for the ephrin-A1 mediated spine retraction, pointing to a critical role of Cdk5 in conveying signals from extracellular cues to actin cytoskeleton at synapses. Taken together, understanding the precise regulation of Cdk5 and its downstream targets at synapses would provide important insights into the multi-regulatory roles of Cdk5 in actin remodeling during dendritic spine development.

Excitatory synaptic transmission occurs primarily at dendritic spines, small protrusions that extend from dendritic shafts. Emerging studies have shown that dendritic spines are dynamic structures which undergo changes in size, shape and number during development, and remain plastic in adult brain.1 Regulation of spine morphology has been implicated to associate with changes of synaptic strength.2 For example, enlargement and shrinkage of spines was reported to associate with certain forms of synaptic plasticity, i.e., long-term potentiation and long time depression, respectively.3 Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of spine morphogenesis would provide insights into synapse development and plasticity. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as the Ephs are known to play critical roles in regulating spine morphogenesis. Eph receptors are comprised of 14 members, which are classified into EphAs and EphBs according to their sequence homology and ligand binding specificity. With a few exceptions, EphAs typically bind to A-type ligands, whereas EphBs bind to B-type ligands. During development of the central nervous system (CNS), ephrin-Eph interactions exert repulsive/attractive signaling, leading to regulation of axon guidance, topographic mapping and neural patterning.4 Activated Ephs trigger intracellular signaling cascades, which subsequently lead to remodeling of actin cytoskeleton through tyrosine phosphorylation of its target proteins or interaction with various cytoplasmic signaling proteins. Intriguingly, emerging studies have revealed novel functions of Ephs in synapse formation and synaptic plasticity.5 Specific Ephs expressed in dendritic spines of adult brain are implicated in regulating spine morphogenesis, i.e., EphBs promote spine formation and maturation, while EphA4 induces spine retraction.6,7

In the adult hippocampus, EphA4 is localized to the dendritic spines.7,8 Activation of EphA4 at the astrocyte-neuron contacts, triggered by astrocytic ephrin-A3, leads to spine retraction and results in a reduction of spine density.7 It has been well established that actin cytoskeletal rearrangement is critical for spine morphogenesis, and is controlled by a tight regulation of Rho GTPases including Rac1/Cdc42 and RhoA. Antagonistic regulation of Rac1/Cdc42 and RhoA has been observed to precede changes in spine morphogenesis, i.e., activation of Rac1/Cdc42 and inhibition of RhoA is involved in spine formation, and vice versa in spine retraction.9 Rho GTPases function as molecular switches that cycle between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. The activation status of GTPase is regulated by an antagonistic action of guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) which enhance the exchange of bound GDP for GTP, and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) which increase the intrinsic rate of hydrolysis of bound GTP.10 Previous studies have implicated that Rho GTPases provides a direct link between Eph and actin cytoskeleton in diverse cellular processes including spine morphogenesis.11 In particular, EphBs regulate spine morphology by modulating the activity of Rho GTPases, thereby leading to rearrangement of actin networks.12–14 Although EphA4 activation results in spine shrinkage, the molecular mechanisms that underlie the action of EphA4 at dendritic spines remain largely unclear.

Work from our laboratory recently demonstrated a critical role of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) in mediating the action of EphA4 in spine morphogenesis through regulation of RhoA GTPase.15 Cdk5 is a proline-directed serine/threonine kinase initially identified to be a key regulator of neuronal differentiation, and has been implicated in actin dynamics through regulating the activity of Pak1, a Rac effector, during growth cone collapse and neurite outgrowth.16 We found that EphA4 stimulation by ephrin-A ligand enhances Cdk5 activity through phosphorylation of Cdk5 at Tyr15. More importantly, we demonstrated that ephexin1, a Rho GEF, is phosphorylated by Cdk5 in vivo. Ephexin1 was reported to transduce signals from activated EphA4 to RhoA, resulting in growth cone collapse during axon guidance.17,18 Interestingly, we found that ephexin1 is highly expressed at the post-synaptic densities (PSDs) of adult brains.15 Loss of ephexin1 in cultured hippocampal neurons or in vivo perturbs the ability of ephrin-A to induce EphA4-dependent spine retraction. The loss of ephexin1 function in spine morphology can be rescued by reexpression of wild-type ephexin1, but not by expression of its phosphorylation-deficient mutant. Our findings therefore provide important evidence that phosphorylation of ephexin1 by Cdk5 is required for the EphA4-dependent spine retraction.

Molecular mechanisms underlying the action of Cdk5/ephexin1 on actin networks in EphA4-mediated spine retraction is just beginning to be unraveled. It was reported that activation of EphA4-signaling induces tyrosine phosphorylation of ephexin1 through Src family kinases (SFKs), and promotes its exchange activity towards RhoA.17 Interestingly, mutation of the Cdk5 phosphorylation sites of ephexin1 attenuates the Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of ephexin1 at Tyr87 upon EphA4 activation. These findings suggest that Cdk5 is the “priming” kinase for ephexin1. We propose that EphA4 activation by ephrin-A ligand increases Cdk5 activity, leading to phosphorylation and priming of ephexin1 for the subsequent phosphorylation of ephexin1 by Src kinase at Tyr87, resulting in an increase of its exchange activity towards RhoA. Thus, regulation of Cdk5 activity might indirectly control the phosphorylation of ephexin1 by Src. It is tempting to speculate that phosphorylation of ephexin1 by Cdk5 at the amino-terminal region leads to a conformational change of protein, thus facilitating the access of Tyr87 site on ephexin1 to Src kinase. Whereas accumulating evidence have pointed to a pivotal role of various GEFs including Tiam1, intersectin and kalirin in regulating spine morphogenesis, the involvement of GAPs is not clear. For example, oligophrenin-1, a Rho GAP, is implicated in maintaining the spine length through repressing RhoA activity.19 Thus, it is conceivable that a specific GAP is involved in EphA4-dependent spine retraction. Recently, we found that α2-chimaerin, a Rac GAP, regulates EphA4-dependent signaling in hippocampal neurons (Shi and Ip, unpublished observations). Taken into consideration that α2-chimaerin is enriched in the PSDs, α2-chimaerin is a likely candidate that cooperates with ephexin1 during EphA4-dependent spine retraction.

In addition to stimulation of the RTK signaling cascade following EphA4 receptor activation, clustering of EphA4 signaling complex is required for eliciting maximal EphA4 function.20 It is tempting to speculate that Cdk5 also regulates the formation of EphA4-containing clusters in neurons. Indeed, Cdk5-/- neurons show reduced size of EphA4 clusters upon ephrin-A treatment, suggesting that Cdk5 regulates the recruitment of downstream signaling proteins to activate EphA4. Moreover, since ephrinA-EphA4 interaction stimulates the activity of Cdk5 at synaptic contacts, it is possible that Cdk5 might play additional roles at the post-synaptic regions through phosphorylation of its substrates. For example, PSD-95, the major scaffold protein in the PSDs, and NMDA receptor subunit NR2A are both substrates for Cdk5. Interestingly, phosphorylation of these proteins by Cdk5 has been implicated in regulating the clustering of neurotransmitter receptors as well as synaptic transmission.21,22 Consistent with these observations, spatial distribution of neurotransmitter receptors at neuromuscular synapses is altered and abnormal neurotransmission is observed in Cdk5-/- mice.23 Thus, further analysis to delineate the precise roles of Cdk5 in EphA4-dependent synapse development, including regulation of neurotransmitter receptor clustering, is required.

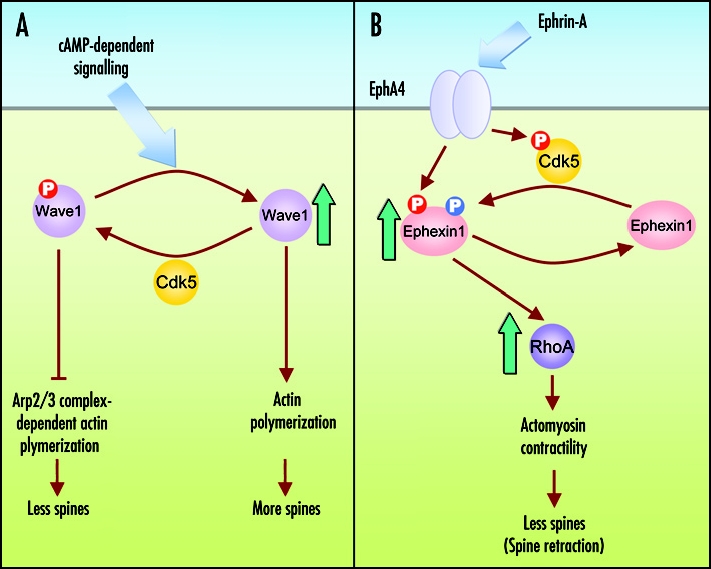

Recently, Cdk5 was shown to regulate dendritic spine density and shape through controlling the phosphorylation status of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-family verprolin homologous protein 1 (WAVE-1), a critical component of actin cytoskeletal network.24 In particular, phosphorylation of WAVE-1 by Cdk5 prevents actin from Arp2/3 complex-dependent polymerization and leads to a loss of dendritic spines at basal state, while reduced Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of WAVE-1 through cAMP-dependent dephosphorylation leads to an enhanced actin polymerization and increased number of spines. It is interesting to note that phosphorylation of ephexin1 and WAVE-1 by Cdk5 both results in a reduction of spine density. Whether a concerted phosphorylation of these proteins at synapses by Cdk5 plays a role in synaptic plasticity awaits further studies. Precise regulation of Cdk5 activity is unequivocally important to maintain its proper functions at synaptic contacts. Activation of Cdk5 is mainly dependent on its binding to two neuronal-specific activators, p35 or p39, and its activity can be enhanced upon phosphorylation at Tyr15.

While the signals that lie upstream of Cdk5 have barely begun to be unraveled, Cdk5 has been demonstrated to be a key downstream regulator of signaling pathways activated by extracellular cues such as neuregulin, BDNF and semaphorin. To the best of our knowledge, ephrin-EphA4 signaling is the first extracellular cue that has been identified to phosphorylate Cdk5 and promote its activity at CNS synapses.15,25 Since BDNF-TrkB and semaphorin3A-fyn signaling have also been implicated in synapse/ spine development, it is of importance to examine whether Cdk5 is the downstream integrator of these signaling events at synapses during spine morphogenesis.26,27

Although accumulating evidence highlights a role of Cdk5 in spatial learning and synaptic plasticity, the molecular mechanisms underlying the action of Cdk5 are largely unclear.28,29 With the recent findings that reveal the critical involvement of Cdk5 in the regulation of Rho GTPases to affect spine morphology, it can be anticipated that precise regulation of actin dynamics by Cdk5 at synapses will be an important mechanism underlying synaptic plasticity in the adult brain.

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of actin regulators by Cdk5 during dendritic spine morphogenesis. (A) In striatal and hippocampal neurons, phosphorylation of WAVE-1 by Cdk5 at basal condition prevents WAVE-1-mediated actin polymerization and leads to a loss of dendritic spines. However, activation of cyclic AMP-dependent signaling by neurotransmitter such as dopamine, reduces the Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of WAVE-1 in these neurons. Dephosphorylation of WAVE-1 promotes actin polymerization and results in an increased number of mature dendritic spines. (B) In mature hippocampal neurons, activation of EphA4 by ephrin-A increases Cdk5-dependent of ephexin1. The phosphorylation of ephexin1 by Cdk5 facilitates its EphA4-stimulated GEF activity towards RhoA activation and leads to spine retraction.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/4617

References

- 1.Ethell IM, Pasquale EB. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine development and remodeling. Progress in Neurobiology. 2005;75:161. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlisle HJ, Kennedy MB. Spine architecture and synaptic plasticity. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:182. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luscher C, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, Muller D. Synaptic plasticity and dynamic modulation of the postsynaptic membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:545. doi: 10.1038/75714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3:475. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murai KK, Pasquale EB. Eph receptors, ephrins, and synaptic function. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:304–314. doi: 10.1177/1073858403262221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henkemeyer M, Itkis OS, Ngo M, Hickmott PW, Ethell IM. Multiple EphB receptor tyrosine kinases shape dendritic spines in the hippocampus. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1313–1326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murai KK, Nguyen LN, Irie F, Yamaguchi Y, Pasquale EB. Control of hippocampal dendritic spine morphology through ephrin-A3/EphA4 signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:153–160. doi: 10.1038/nn994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tremblay ME, Riad M, Bouvier D, Murai KK, Pasquale EB, Descarries L, Doucet G. Localization of EphA4 in axon terminals and dendritic spines of adult rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:691–702. doi: 10.1002/cne.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govek EE, Newey SE, Van Aelst L. The role of the Rho GTPases in neuronal development. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watabe-Uchida M, Govek EE, Van Aelst L. Regulators of Rho GTPases in neuronal development. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10633–10635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4084-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noren NK, Pasquale EB. Eph receptor-ephrin bidirectional signals that target Ras and Rho proteins. Cellular Signalling. 2004;16:655. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolias KF, Bikoff JB, Kane CG, Tolias CS, Hu L, Greenberg ME. The Rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 mediates EphB receptor-dependent dendritic spine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702044104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moeller ML, Shi Y, Reichardt LF, Ethell IM. EphB receptors regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis through the recruitment/phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and RhoA activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1587–1598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penzes P, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Schiller MR, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Huganir RL. Rapid induction of dendritic spine morphogenesis by trans-synaptic ephrinB-EphB receptor activation of the Rho-GEF kalirin. Neuron. 2003;37:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu WY, Chen Y, Sahin M, Zhao XS, Shi L, Bikoff JB, Lai KO, Yung WH, Fu AK, Greenberg ME, Ip NY. Cdk5 regulates EphA4-mediated dendritic spine retraction through an ephexin1-dependent mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nn1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikolic M, Chou MM, Lu W, Mayer BJ, Tsai LH. The p35/Cdk5 kinase is a neuron-specific Rac effector that inhibits Pak1 activity. Nature. 1998;395:194. doi: 10.1038/26034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahin M, Greer PL, Lin MZ, Poucher H, Eberhart J, Schmidt S, Wright TM, Shamah SM, O'Connell S, Cowan CW, Hu L, Goldberg JL, Debant A, Corfas G, Krull CE, Greenberg ME. Eph-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of ephexin1 modulates growth cone collapse. Neuron. 2005;46:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Goldberg JL, Estrach S, Sahin M, Hu L, Bazalakova M, Neve RL, Corfas G, Debant A, Greenberg ME. EphA receptors regulate growth cone dynamics through the novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor ephexin. Cell. 2001;105:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govek EE, Newey SE, Akerman CJ, Cross JR, Van der Veken L, Van Aelst L. The X-linked mental retardation protein oligophrenin-1 is required for dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:364. doi: 10.1038/nn1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egea J, Nissen UV, Dufour A, Sahin M, Greer P, Kullander K, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Greenberg ME, Kiehn O, Vanderhaeghen P, Klein R. Regulation of EphA 4 kinase activity is required for a subset of axon guidance decisions suggesting a key role for receptor clustering in Eph function. Neuron. 2005;47:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morabito MA, Sheng M, Tsai LH. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates the N-terminal domain of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 in neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:865–876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4582-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li BS, Sun MK, Zhang L, Takahashi S, Ma W, Vinade L, Kulkarni AB, Brady RO, Pant HC. Regulation of NMDA receptors by cyclin-dependent kinase-5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12742–12747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211428098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu AK, Ip FC, Fu WY, Cheung J, Wang JH, Yung WH, Ip NY. Aberrant motor axon projection, acetylcholine receptor clustering, and neurotransmission in cyclin-dependent kinase 5 null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15224–15229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507678102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Sung JY, Ceglia I, Lee KW, Ahn JH, Halford JM, Kim AM, Kwak SP, Park JB, Ho Ryu S, Schenck A, Bardoni B, Scott JD, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Phosphorylation of WAVE1 regulates actin polymerization and dendritic spine morphology. Nature. 2006;442:814–817. doi: 10.1038/nature04976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung ZH, Chin WH, Chen Y, Ng YP, Ip NY. Cdk5 is involved in BDNF-stimulated dendritic growth in hippocampal neurons. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita A, Yamashita N, Sasaki Y, Uchida Y, Nakajima O, Nakamura F, Yagi T, Taniguchi M, Usui H, Katoh-Semba R, Takei K, Goshima Y. Regulation of dendritic branching and spine maturation by semaphorin3A-Fyn signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2971–2980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5453-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji Y, Pang PT, Feng L, Lu B. Cyclic AMP controls BDNF-induced TrkB phosphorylation and dendritic spine formation in mature hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:164–172. doi: 10.1038/nn1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung ZH, Fu AK, Ip NY. Synaptic roles of Cdk5: Implications in higher cognitive functions and neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2006;50:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawasli AH, Benavides DR, Nguyen C, Kansy JW, Hayashi K, Chambon P, Greengard P, Powell CM, Cooper DC, Bibb JA. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 governs learning and synaptic plasticity via control of NMDAR degradation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:880–886. doi: 10.1038/nn1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]