Abstract

One of the main components of pectin, a primary constituent of higher plant cell walls, is rhamnogalacturonan I. This polymer comprised of linked alternating rhamnose and galacturonic acid residues is decorated with side chains composed of arabinose and galactose residues. At present, the function of these side chains is not fully understood. Our research on Southern African resurrection plants, plants that are capable of surviving severe dehydration (desiccation), has revealed that their cell walls are capable of extreme flexibility in response to water loss. One species, Myrothamnus flabellifolia, has evolved a constitutively protected leaf cell wall, composed of an abundance of arabinose polymer side chains, suggested to be arabinans and/or arabinogalactans, associated with the pectin matrix. In this article, we propose a hypothetical model that explains how the arabinan rich pectin found in the leaves of this desiccation-tolerant plant permits almost complete water loss without deleterious consequences, such as irreversible polymer adhesion, from occurring. Recent evidence suggesting a role for pectin-associated arabinose polymers in relation to water dependent processes in other plant species is also discussed.

Key words: arabinans, cell wall, desiccation, resurrection, rehydration, rhamnogalacturonan I

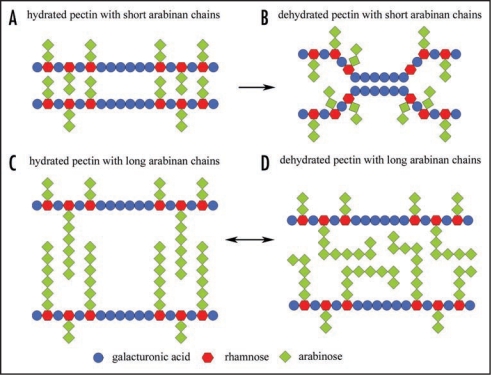

The flowering plant cell wall is a composite structure consisting of a skeletal framework of cellulose and hemicellulose embedded within a matrix of pectin polysaccharides and cell wall glycoproteins.1,2 The pectin matrix, in turn, is composed of three primary types of polysaccharides, these being rhamnogalacturonan I (RGI), rhamnogalacturonan II (RGII) and homogalacturonan (HG).1 RGII is a complex polysaccharide, consisting of many unusual sugar moieties, and is not present in large amounts in the wall.3 HG is effectively a linear homopolymer of galacturonic acid and is believed to facilitate the formation of tight junctions, ‘egg boxes’, by complexing with calcium ions present in the cell wall.1 RGI is a polymer composed of a backbone of alternating glycosidically linked rhamnose and galacturonic acid residues.1 Side chains, consisting of either arabinogalactan polymers or linear chains of arabinans and/or galactans, are then attached to the rhamnose residues of the RGI backbone.1 The manner with which these polymers are attached or become entangled with each other and cellulosic polymers to form the pectin matrix has been a matter of debate. The classical theory is that the RGI and HG polymers alternate with each other as block polymers and that the side chains interact with neighbouring polysaccharide chains. Recently, this standard theory has been questioned and an argument whereby the HG polymers are actually side chains of a RGI backbone polymer has been advanced.4 Nevertheless, the complexity of pectin polysaccharides is such that ascribing definitive functions to this matrix of polysaccharides has proven quite difficult. The physical properties of the pectin matrix suggest a number of possible functions. The water binding properties of the galacturonic acid residues indicate that polymers containing these groups have the capacity to hydrate and swell and so possibly help maintain polymer separation in the wall.5 The side chains of RGI include arabinan and galactan polymers which have been shown to be highly mobile6,7,8 with the potential to interact with each other forming a temporally entangled matrix.9 It is also believed that arabinan chains, which have been shown to contain ferulate residues attached to terminal arabinose groups, are able to oxidatively cross-link via the formation of diferulate bridges between arabinan chains that originate on separate RGI polysaccharides.10 The pectin matrix is now believed to contain sub-domains of RGI, HG and RGII which may interact with different polysaccharide components of the cell wall such as cellulose or xyloglucan.11,12 Hence, it is possible that the pectin matrix may form these associations with other polysaccharides via covalent9 and/or non-covalent11 (e.g., H-bonding) interactions and in so doing ensure the integrity of the wall and its polymer organisation. Although a number of general functions, such as hydration and ion binding, have been proposed for the pectin matrix, in particular the RGI polymer and its neutral side chains, there has been difficulty in elucidating specific functions for these polysaccharides. A number of molecular genetic studies have been performed with the aim of establishing specific functions for the RGI side chains. A recent study showed that genetic removal of the arabinan side chains in the cell walls of Nicotiana plumbaginfolia results in the formation of a non-organogenic callus culture with loosely attached cells.13 Furthermore, it has been shown that ‘in muro’ fragmentation of the RG1 backbone in Solanum tuberosum results in abnormal development of the periderm.14 This suggests that these side chains may play at least some role in normal cell attachment and cell development. However, the real problem is that no obvious phenotypic differences between wild type and mutant plants (in which neutral side chains have been modified) have been observed.15,16,17 It may be that the conditions under which phenotypic differences between wild type and mutant plants would arise have not yet been investigated. We believe the water binding and attachment properties of the pectin matrix are particularly important. This is especially so given the role pectin plays in the middle lamella ensuring attachment of cells to each other and in the formation of the apoplast where water mediated transport of solutes occurs.1 Our research has focused on a group of Southern African plants termed ‘Resurrection plants’ because of their unique ability to survive severe dehydration (desiccation) to an almost air-dry state.18 We have been interested in how the cell walls of angiosperm resurrection plants such as Craterostigma wilmsii19,20 and Myrothamnus flabellifolia21,22 may have become adapted to survive this extreme water deficit stress (desiccation). We have shown that in the case of the Myrothamnus flabellifolia leaf cell wall, which becomes considerably folded when dried, does not undergo dramatic changes in composition or polymer location in response to desiccation.21 Rather we propose that this plant has evolved a constitutively protected cell wall which is able to undergo repeated cycles of desiccation and rehydration.21,22 We have observed that the pectin component of the leaf cell wall in this species was unusually rich in arabinose polymers, most likely arabinan and arabinogalactan in nature, which we advanced was the reason that the cell wall of this species was able to tolerate desiccation.21 Here we provide a simple model (Fig. 1) whereby the arabinan side chains of the pectin polysaccharides are responsible for possibly buffering/replacing the lost water during desiccation and in so doing prevent the formation of tight junctions (e.g., egg boxes) or strong H-bonding interactions between the normally separate ‘skeletal’ polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose microfibrils and xyloglucan tethers) embedded in the pectin matrix. Our model is supported by the observation that cell wall arabinans play a crucial role in the response of guard cells to turgor pressure.23 It was shown that removal of arabinans by enzymatic digestion of leaf strips of Commelina communis resulted in locking of the guard cell walls in either the open or closed position.23 Additional roles for arabinan polymers in cell walls have recently been implied with respect to the salt tolerance of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum,24 ensuring hydration of the seed endosperm of Gleditsia triacanthos during germination25 and the tolerance of tropical legume seeds to dehydration.26 We believe that the arabinan side chains of RGI play a critical role in the ability of cell walls to remain flexible during plant growth and may have important functions in relation to the water content of the cell. Further studies aimed at determining the relationship between wall water content, RGI side chains and cell wall flexibility may reveal hitherto unsuspected functions for these polysaccharides in the life of the plant.

Figure 1.

A model proposing the role of arabinose rich pectin polymers in stabilising the cell wall against water loss. (A) Pectin consisting of short arabinan chains in the hydrated state, (B) pectin consisting of short arabinan chains in the dehydrated state; (C) pectin consisting of long arabinan chains in the hydrated state; (D) pectin consisting of long arabinan chains in the dehydrated state. The likelihood of irreversible tight junctions (e.g., egg boxes) forming in arabinan poor cell walls during dehydration is demonstrated in (B) while the reversible buffering effect of arabinan rich cell walls is proposed in (D) as would possibly occur in Myrothamnus flabellifolia. For simplicity arabinan chains not participating in the buffering interactions between the RGI backbone chains have been shortened to two arabinose residues in length. Note in (A) and (B) all arabinan chains are two arabinose residues in length.

Abbreviations

- RGI

rhamnogalacturonan I

- RGII

rhamnogalacturonan II

- HG

homogalacturonan

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/4959

References

- 1.Brett CT, Waldron K. Physiology and Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls. London: Chapman and Hall Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: Consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill MA, Ishii T, Albersheim P, Darvill AG. Rhamnogalacturonan II: Structure and function of a borate cross-linked cell wall pectic polysaccharide. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:109–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincken J, Schols HA, Oomen RJ, McCann MC, Ulvskov P, Voragen AG, Visser RG. If homogalacturonan were a side chain of rhamnogalacturonan I: Implications for cell wall architecture. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1781–1789. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belton PS. NMR and the mobility of water in polysaccharide gels. Int J Biol Macromol. 1997;21:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(97)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster TJ, Ablett S, McCann MC, Gidley MJ. Mobility resolved 13C-NMR spectroscopy of primary plant cell walls. Biopolymers. 1996;39:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renard GMGC, Jarvis MC. A cross polarization magic angle spinning 13C nuclear magnetic resonance study of polysaccharides in sugar beet cell walls. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:1315–1322. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.4.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha MA, Viëtor R, Jardine GD, Apperley DC, Jarvis MC. Conformation and mobility of the arabinan and galactan side-chains of pectin. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1817–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zykwinska A, Rondeau-Mouro C, Thibault JF, Ralet MC. Alkaline extractability of pectic arabinan and galactan and their mobility in sugar beet and potato cell walls. Carbohyd Polym. 2006;65:510–520. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ralet MC, André-Leroux G, Quéméner B, Thibault JF. Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) pectins are covalently cross-linked through diferulic bridges in the cell wall. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2800–2814. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zykwinska AW, Ralet MCJ, Garnier CD, Thibault JFJ. Evidence for in vitro binding of pectin side chains to cellulose. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:397–407. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yapo BM, Lerouge P, Thibault JF, Ralet MC. Pectins from citrus peel cell walls contain homogalacturonans homogenous with respect to molar mass, rhamnogalacturonan I and rhamnogalacturonan II. Carbohyd Polym. 2007;69:426–435. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwai H, Ishii T, Satoh S. Absence of arabinan in the side chains of the pectic polysaccharides strongly associated with cell walls of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia non-organogenic callus with loosely attached constituent cells. Planta. 2001;213:907–915. doi: 10.1007/s004250100559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oomen RJ, Doeswijk-Voragen CH, Bush MS, Vincken JP, Borkhardt B, van den Broek LA, Corsar J, Ulvskov P, Voragen AGJ, McCann MC, Visser RGF. In muro fragmentation of the rhamnogalacturonan I backbone in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) results in a reduction and altered location of the galactan and arabinan side-chains and abnormal periderm development. Plant J. 2002;30:403–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orfila C, Seymour GB, Willats WGT, Huxham IM, Jarvis MC, Dover CJ, Thompson AJ, Knox JP. Altered middle lamella homogalacturonan and disrupted deposition of (1/5)-a-L-Arabinan in the pericarp of Cnr, a ripening mutant of tomato. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:210–221. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulvskov P, Wium H, Bruce D, Jørgensen B, Qvist KB, Skjøt M, Hepworth D, Borkhardt B, Sørensen SO. Biophysical consequences of remodeling the neutral side chains of rhamnogalacturonan I in tubers of transgenic potatoes. Planta. 2005;220:609–620. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harholt J, Jensen JK, Sørensen SO, Orfila C, Pauly M, Scheller HV. ARABINAN DEFICIENT 1 Is a putative arabinosyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of pectic arabinan in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:49–58. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.072744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicré M, Farrant JM, Driouich A. Insights into the cellular mechanisms of desiccation tolerance among angiosperm resurrection plant species. Plant Cell Environm. 2004;27:1329–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vicré M, Sherwin HW, Driouich A, Jaffer MA, Farrant JM. Cell wall characteristics and structure of hydrated and dry leaves of the resurrection plant Craterostigma wilmsii, a microscopical study. J Plant Physiol. 1999;155:719–726. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vicré M, Lerouxel O, Farrant J, Lerouge P, Driouich A. Composition and desiccation-induced alterations in the cell wall of the resurrection plant Craterostigma wilmsii. Physiol Plant. 2004;120:229–239. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore JP, Nguema-Ona E, Chevalier L, Lindsey GG, Brandt WF, Lerouge P, Farrant JM, Driouich A. Response of the leaf cell wall to desiccation in the resurrection plant Myrothamnus flabellifolius. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:651–662. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.077701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore JP, Lindsey GG, Farrant JM, Brandt W. An overview of the biology of the desiccation tolerant resurrection plant Myrothamnus flabellifolia. Ann Bot. 2007;99:211–217. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones L, Milne JL, Ashford D, McQueen-Mason SJ. Cell wall arabinan is essential for guard cell function. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11783–11788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832434100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galkina Y, Chemikosova S, Gorshkova T, Alexandrova S, Holodova V, Kuznetsov VI. Cell wall involvement in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum reaction to salinity; Ninth International Cell Wall Meeting; Toulouse: France. 2001. p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro DA, Cerezo AS, Stortz CA. NMR spectroscopy and chemical studies of an arabinan-rich system from the endosperm of the seed of Gleditsia triacanthos. Carbohyd Res. 2002;337:255–263. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mescia T, Caccere R, Braga M, Figueiredo-Ribeiro RC. Cell wall changes during maturation of tropical legume seeds differing in the tolerance to desiccation; Eleventh International Cell Wall Meeting; Copenhagen, Denmark. 2007. p. 56. [Google Scholar]