Abstract

Endothelial and platelet P-selectin (CD62P) and leukocyte integrin αMβ2 (CD11bCD18, Mac-1) are cell adhesion molecules essential for host defense and innate immunity. Upon inflammatory challenges, P-selectin binds to PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1, CD162) to mediate neutrophil rolling, during which integrins become activated by extracellular stimuli for their firm adhesion in a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-dependent mechanism. Here we show that cross-linking of PSGL-1 by dimeric or multimeric forms of platelet P-selectin, P-selectin receptor-globulin, anti-PSGL-1 mAb and its F(ab′)2 induced adhesion of human neutrophils to fibrinogen (Fg) and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1, CD54) and triggered a moderate clustering of αMβ2, but monomeric forms of soluble P-selectin and anti-PSGL-1 Fab did not. Interestingly, P-selectin did not induce a detectable interleukine-8 (IL-8) secretion (<0.1 ng/ml) in 30 minutes, whereas a high concentration of IL-8 (>50 ng/ml) was required to increase neutrophil adhesion to Fg. P-selectin-induced neutrophil adhesion was significantly inhibited by PP2 (a Src kinase inhibitor), but not by pertussis toxin (PTX; a GPCR inhibitor). Activated platelets also increased neutrophil binding to fibrinogen and triggered tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins. Our results indicate that P-selectin-induced integrin activation (Src kinase-dependent) is distinct from that elicited by cytokines, chemokines, chemoattractants (GPCR-dependent), suggesting that these two signal transduction pathways may cooperate for maximal activation of leukocyte integrins.

Key words: P-selectin (CD62P), P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), integrins, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), human neutrophils, cell adhesion

Introduction

Leukocyte recruitment involves a cascade of cellular events including initial attachment (tethering), rolling, weak and firm adhesion, diapedesis, transendothelial migration and chemotaxis.1 Selectins interact with their cognate glycoprotein ligands to mediate tethering, rolling and weak adhesion while integrins interact with the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell adhesion molecules for firm adhesion and signal transduction, which eventually triggers diapedesis and transendothelial migration.1–3 The emigrated leukocytes are guided by the gradients of various chemokines and chemoattractants to move to their destination where the insult occurs, such as the site of infection or tissue injury.

P-selectin (CD62P) is a pre-synthesized protein stored in the Weibel-Palade body of endothelial cells and the α-granule of platelets.4,5 Upon inflammatory and thrombogenic challenges, P-selectin rapidly translocates to the cell surface by exocytosis and interacts with a cell-surface sialomucin called P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1, CD162) to mediate tethering, rolling and weak adhesion of leukocytes on the activated endothelial cells and heterotypic aggregation of the activated platelets to leukocytes.5–7

The integrin family of cell adhesion molecules consists of two noncovalently associated α and β subunits. The β2 subunit, along with four-specific α subunits of αM, αL, αX and αD, is expressed exclusively on leukocytes. αMβ2(Mac-1, CD11bCD18) is a principal neutrophil integrins, which, upon inflammatory challenges, undergoes conformational change for high affinity/avidity binding to its ligands, such as fibrinogen (Fg) and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1, CD54).8–13

The close proximity and the timing rendered by selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling are generally believed to facilitate β2-integrin activation by extracellular stimuli, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), platelet activating factor (PAF), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1, CXCL12) and several others.14–15 They are released from and displayed on the activated endothelial lining of the vessel walls, which dynamically forms the “adhesive zone” with the contact site of rolling leukocytes in situ and locally activates leukocyte integrins in subseconds through pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gi-type heterotrimeric G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs).14 In addition, P-selectin has been shown to activate MAP kinase and induce IL-8 release.16 However, whether Src kinases and GPCRs act as the key downstream signaling mechanisms for P-selectin-induced β2-integrin activation remains undetermined. In the present study, we sought to experimentally investigate this important question.

Materials and Methods

Proteins and antibodies.

Platelet P-selectin (mP-selectin) was isolated from out dated human platelets by PS2 mAb affinity chromatography. It existed in dimeric and oligomeric forms even at the detergent concentrations well above critical micelle concentration.17 Recombinant human P-selectin receptor-globulin (Rg) was prepared as previously described in references 18 and 19. It was characterized as a homodimer,16 with each monomer having two P-selectin (the lectin and epidermal growth factor-like domains followed by the first two complement-like repeats). Recombinant soluble human P-selectin (sP-selectin), which was previously characterized as a monomer20 and recombinant IL-8 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota). Plasminogen-depleted human Fg was from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, Indiana). G1 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking IgG1 mAb to P-selectin) and PS1 (a leukocyte adhesion non-blocking IgG1 mAb to P-selectin) were prepared and characterized as before.18–19 KPL-1 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking IgG1 mAb to PSGL-1) and IL-8 blocking mAb (Cat. No 554726) were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, California). F(ab′)2 and Fab fragments of G1, PS1 and KPL-1 were prepared using ImmunoPure® F(ab′)2 and Fab Preparation Kits (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois). IB4 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking IgG2a mAb to β2 subunit) was purchased from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Virginia) and S1 (a IgG2a mAb to human Slit2)21 was used as the isotype-matched control. Human and mouse IgG were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri).

Neutrophil isolation.

Fresh human blood from healthy volunteers was taken by venopuncture according to the regulations of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Human neutrophils were isolated according to the method described before (ref. 21). The isolated neutrophils were then resuspended in ice cold phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS) for immediate usage. The purity of neutrophils used was routinely >96%.

Adhesion and binding assays.

The 96-well tissue culture plates (Costar®; Cambridge, Massachusets) were immobilized with 20 µg/ml Fg, 5 µg/ml ICAM-1 in PBS (0.1 ml/well) at 4°C over-night. They were post-coated with 0.5% polyvinyl-alcohol (Sigma) at 24°C for two hours followed by washing two times with PBS. Human IgG, P-selectin Rg, mP-selectin, sP-selectin, KPL-1 intact mAb, F(ab′)2 or Fab (all at 10 µg/ml) and IL-8 (100 ng/ml) unless specifically indicated, was added to neutrophils resuspended at 2 x 106/ml in PBS/Ca/BSA (PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mg/ml bovine serum albumin), prior to transferring to each well (0.1 ml/well). For antibody inhibition experiments, 10 µg P-selectin Rg was preincubated with 20 µg G1 F(ab′)2 or PS1 F(ab′)2 in 30 µl PBS/Ca (PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2) at 24°C for 15 minutes. Alternatively, neutrophils were preincubated with IB4 and its isotype-matched control, S1, or IL-8 blocking mAb and its isotype-matched control, 9E10 (all at 10 µg/ml). For chemical compound inhibition experiments, neutrophils were incubated with the indicated concentration of various inhibitors, such as PP2, daidzein, genistein or PTX (all were purchased from Calbiochem, La Jolla, California), at 24°C for 25 minutes, before adding P-selectin Rg. For secretion experiments, neutrophils (2 x 106 /ml) were incubated with 10 µg/ml human IgG or P-selectin Rg at 37°C for 25 minutes. Following centrifugation, the supernatants were harvested individually and 20 µg/ml G1 F(ab′)2 or PS1 F(ab′)2 was added to the supernatants containing the previously added P-selectin Rg for 15 minutes at 24°C. These supernatants were then incubated with the same amount of fresh neutrophils for five minutes at 24°C. The cells were kept in the treated wells for 25 minutes at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. After incubation at 37°C for 25 minutes in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, non-adherent cells were carefully removed by washing three times with PBS. The adherent cells were quantified using a myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay as described before.22 MPO activity was converted to neutrophil numbers using a standard curve that was generated by measurements of enzyme activity derived from a series dilution of known numbers of neutrophils.

IL-8 secretion.

Neutrophils, at a concentration of 4 x 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, were then incubated with plain buffer, 10 µg/ml human IgG and P-selectin Rg, DMSO, 10 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) at 37°C for indicated time. After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected for measurements of IL-8 by IL-8 ELISA assay kit (R&D Systems).

Confocal microscopy.

Neutrophils were resuspended at 2 x 106/ml in PBS/Ca/BSA. They were incubated with 10 µg/ml human IgG and P-selectin Rg, or 10 nM PMA for 30 minutes at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. For chemical compound inhibition experiments, neutrophils were incubated with the indicated concentration of PP2, daidzein, genistein or PTX at 24°C for 25 minutes before adding P-selectin Rg. The samples were then immediately cooled down on ice and centrifuged at 1,600 rpm at 4°C for five minutes. They were resuspended in 0.2 ml PBS/Ca/BSA and incubated with 2 µg OKM1 (a mAb to αM subunit) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution) on ice for 30 minutess with end to end rotation. After washing twice, they were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde on ice for 45 minutes. Following centrifugation, they were resuspended in mowiol, plated on a glass coverslip and observed under a Leica 488 nm laser scanning microscope.22

Platelet isolation and activation.

Fresh human venous blood was centrifuged at 200 g for ten minutes. The plasma was centrifuged at 1,400g for ten minutes. After removal of supernatant, fresh isolated platelets were activated by 0.5 unit/ml thrombin at 37°C for five minutes and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Following washing three times with PBS, platelets were incubated with neutrophils accordingly.

Results

Effect of P-selectin on adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1.

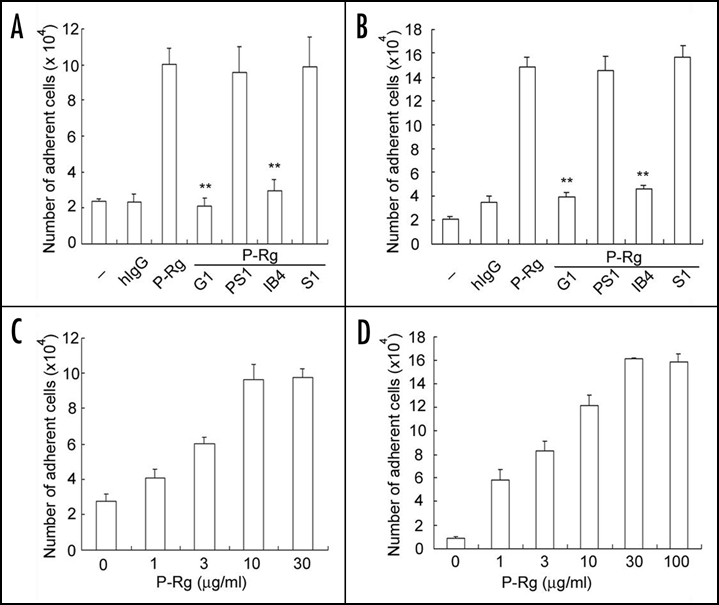

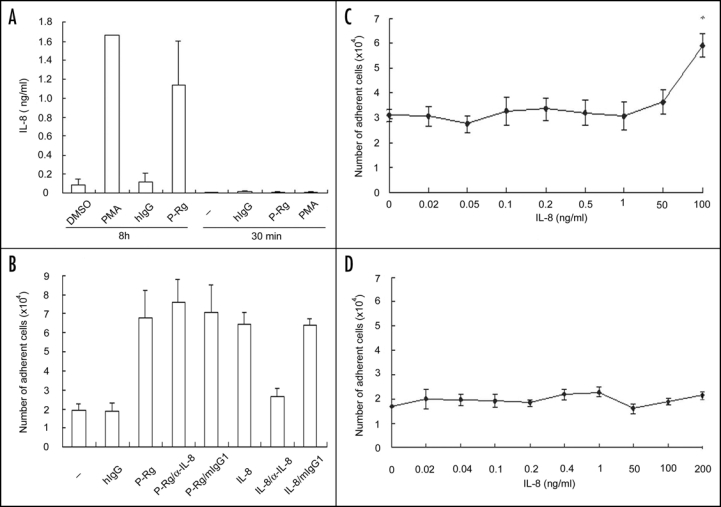

To investigate the effect of P-selectin on αMβ2 activity, we examined P-selectin-induced changes in the adhesion of human neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1. In this experiment, freshly isolated human neutrophils were incubated with recombinant P-selectin Rg and then transferred to the 96-well tissue culture plates immobilized with Fg or ICAM-1. Compared to buffer or human IgG (hIgG; used as a negative control), P-selectin Rg clearly increased the numbers of neutrophils bound to Fg (Fig. 1A) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 1B). Preincubation of P-selectin Rg with G1 F(ab′)2 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to P-selectin), but not with PS1 F(ab′)2 (a leukocyte adhesion non-blocking mAb to P-selectin), neutralized the enhanced adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1. Preincubation of neutrophils with IB4 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to β2 subunit), but not with S1 (an isotype-matched irrelevant mAb), also neutralized the P-selectin-enhanced adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1. In addition, P-selectin Rg induced a dose-dependent adhesion of neutrophils to Fg or ICAM-1, with 10 µg/ml P-selectin Rg for a maximal adhesion of neutrophils to Fg (Fig. 1C) and 30 µg/ml P-selectin Rg for a maximal adhesion of neutrophils to ICAM-1 (Fig. 1D). It should be pointed out that the increment in neutrophil adhesion to Fg and ICAM-1 induced by this concentration of P-selectin Rg was routinely larger than three-fold (n > 6), although there was considerable variability among donors. These data confirm the specificities for the interaction of P-selectin with neutrophils and for the interaction of neutrophils with Fg and ICAM-1, respectively.

Figure 1.

P-selectin induces neutrophil adhesion to Fg and ICAM-1. Freshly isolated human neutrophils were incubated with buffer (designated as -), human IgG (hIgG) or P-selectin Rg (P-Rg) and added to the 96-well cell culture plates immobilized with Fg (A and C) and ICAM-1 (B and D). For antibody inhibition experiments, P-selectin Rg was preincubated with G1 F(ab′)2 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to P-selectin) or PS1 F(ab′)2 (a leukocyte adhesion non-blocking mAb to P-selectin). Alternatively, neutrophils were preincubated with IB4 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to CD18) or S1 (an isotype-matched irrelevant mAb). For dose course experiments (C and D), neutrophils were incubated with the indicated amounts of P-selectin Rg. After washing, the bound neutrophils were quantified by measurements of MPO activities. The numbers of bound neutrophils were calculated according to the standard curve of MPO activities derived from the known amounts of neutrophils. All results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of more than three separate experiments. **p < 0.01.

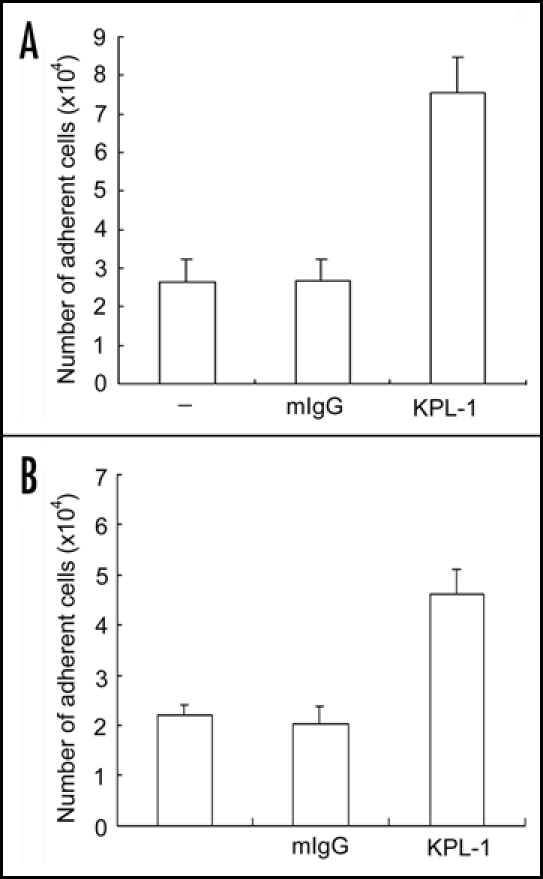

As PSGL-1 is generally believed to act as a principal leukocyte ligand for P-selectin, we proposed that ligament of PSGL-1 with a PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) might also increase adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1. Indeed, incubation of human neutrophils with KPL-1, a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb against PSGL-1, but not with mouse IgG, enhanced adhesion of responding cells to immobilized Fg (Fig. 2A) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 2B). Thus, our data indicate that the binding of P-selectin Rg and PSGL-1 mAb to PSGL-1 can induce the activation of αMβ2 on human neutrophils.

Figure 2.

PSGL-1 mAb increases neutrophil adhesion to Fg and ICAM-1. Neutrophils were incubated with buffer (designated as -), mouse preimmune IgG (mIgG) or KPL-1 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to PSGL-1) and then added to the wells immobilized with Fg (A) and ICAM-1 (B). The cell adhesion assay was performed exactly same as described in figure 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of more than three separate experiments.

Role of P-selectin nultimerization in αMβ2 activity.

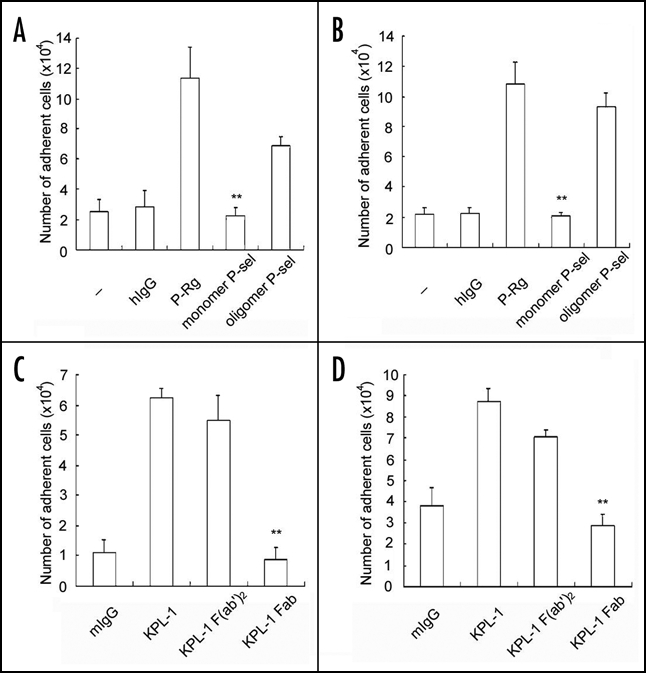

Since P-selectin Rg and KPL-1 mAb are dimers, they may cross-link PSGL-1 on human neutrophils. Notably, the cross-linking of PSGL-1 is biologically relevant, as P-selectin, isolated from human platelets and endothelial cells, exists as dimeric and oligomeric forms even at the detergent concentrations well above the critical micelle concentration.17 To test this hypothesis, we examined the capacity of monomeric sP-selectin to activate the integrin. In contrast to the multimeric P-selectin Rg and platelet P-selectin, monomeric sP-selectin at the same concentration did not enhance neutrophil adhesion to immobilized Fg (Fig. 3A) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 3B). Moreover, KPL-1 mAb (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to PSGL-1) and F(ab')2, but not KPL-1 Fab, enhanced adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized Fg (Fig. 3C) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 3D), consistent with a role of cross-linking of PSGL-1 in αMβ2 activation. Taken together, these data suggest that engagement of PSGL-1 alone is not sufficient for αMβ2 activation, but engagement and cross-linking of PSGL-1 by dimers or higher multimers of P-selectin or PSGL-1 mAb are not only necessary but also sufficient for induction of integrin activation.

Figure 3.

PSGL-1 cross-linking activates αMβ2. Neutrophils were incubated with buffer (-), hIgG, P-Rg, platelet P-selectin (pP-selectin) or soluble P-selectin (sP-selectin) and then transferred to the wells coated with Fg (A) and ICAM-1 (B). Alternatively, neutrophils were incubated with KPL-1 intact mAb, F(ab')2 and Fab and then transferred to the wells coated with Fg (C) and ICAM-1 (D). The cell adhesion assay was performed exactly same as described in Figure 1. All results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of more than three separate experiments. **p < 0.01.

Impact of neutrophil secretion products on αMβ2 activation.

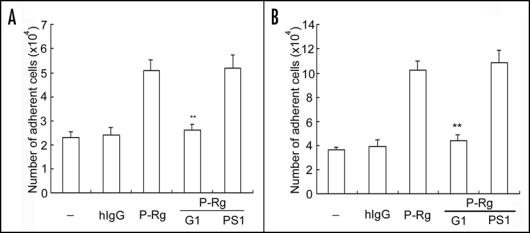

Engagement of PSGL-1 by P-selectin has been shown to stimulate a secretary response in human neutrophils.16 Experiments were thus designed and undertaken to examine whether activation of αMβ2 by P-selectin was indirectly induced by products secreted from the stimulated neutrophils. Indeed, incubation of neutrophils with the supernatant from neutrophils that had been challenged with P-selectin Rg incremented cell adhesion to immobilized Fg (Fig. 4A) or ICAM-1 (Fig. 4B) by ∼two to three-fold when compared to the supernatants derived from untreated or human IgG-treated neutrophils. However, preincubation of the supernatant from the P-selectin Rg treated cells with G1 (a blocking P-selectin mAb), but not PS1 (a non-blocking P-selectin moAb), abrogated the increase in adhesion induced by the supernatants.

Figure 4.

Effects of neutrophil secretion products on αMβ2 activation. Neutrophils were preincubated with hIgG or P-Rg. After centrifugation, supernatants were harvested and further incubated with fresh samples of neutrophils. For antibody inhibition experiments, supernatants from the P-selectin Rg preincubated neutrophils were incubated with G1 or PS1 F(ab′)2, prior to adding to the wells coated with Fg (A) and ICAM-1 (B). The cell adhesion assay was performed same as described in Figure 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of three separate experiments. **p < 0.01.

As IL-8 is among the products secreted from stimulated neutrophils,16 which can in turn activate αMβ2,21 we thus specifically examined whether IL-8 played a role for P-selectin-induced αMβ2 activation. We found that treatment of neutrophils with PMA or P-Rg (8 h) induced the IL-8 secretion; it was <2 ng/ml, even though they were more than ten-fold higher than the negative controls (Fig. 5A). However, no IL-8 secretion could be detected when neutrophils were incubated with buffer, human IgG, P-selectin Rg or even PMA at 37°C for 30 minutes, which was almost the same incubation time as compared to the 25 minute incubation time employed in the cell adhesion assay used in this study. In addition, the dose course experiment showed that >50 ng/ml IL-8 was apparently required to clearly support the increase in the adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized Fg (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, IL-8, even at 100 ng/ml concentration, did not support the increment in the adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized ICAM-1 (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, compared to buffer (-) and human IgG, P-selectin Rg induced neutrophil adhesion to Fg, which was not inhibited by a neutralizing mAb to IL-8. In contrast, this mAb potently inhibited IL-8-elicited neutrophil adhesion to Fg (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the increment in adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1 induced by supernatants from P-selectin treated cells is attributable to the carry-over of P-selectin Rg molecules, but not to endogenous factors, such as IL-8, secreted from the stimulated neutrophils.

Figure 5.

Effects of P-selectin on IL-8 secretion and αMβ2 activation. (A) Neutrophils were incubated with buffer (-), DMSO, PMA, hIgG or P-Rg. The amounts of IL-8 in the supernatants were determined using the IL-8 ELISA assay kit (R&D Systems). The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of three separate experiments. B–D, Neutrophils were incubated with various concentrations of recombinant IL-8, buffer (-), hIgG, P-Rg or IL-8 without or with the neutralizing mAb to IL-8, prior to adding to the wells coated with Fg (B and C) and ICAM-1 (D). The cell adhesion assay was performed same as described in Figure 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the adherent cells determined in triplicate measurements of three separate experiments. **p < 0.01.

Signaling molecules involved in αMβ2 activation.

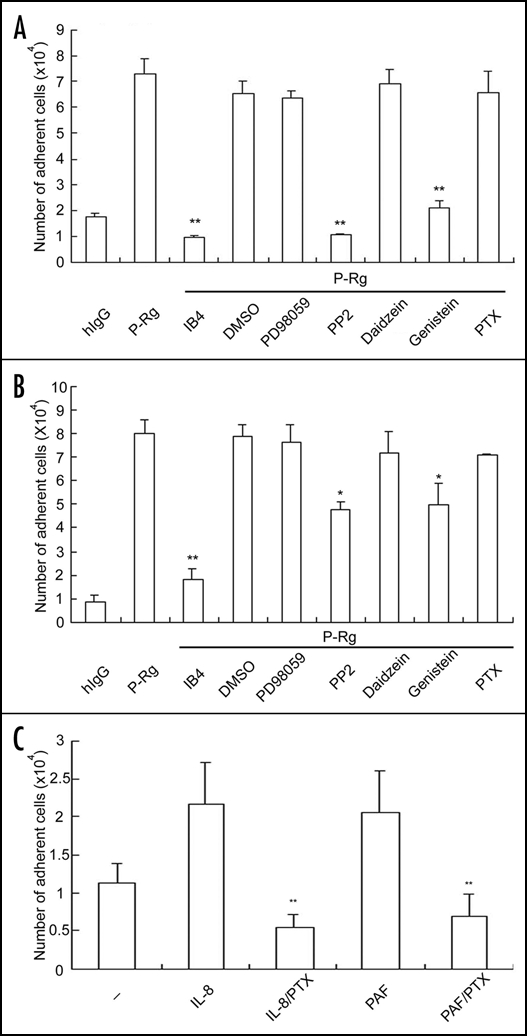

To get insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms, we examined whether inhibitors specific for certain signal transduction pathways inhibited the P-selectin triggered αMβ2 activation. We found that PP2 (a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and genistein (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor; daidzein was used as its inactive structural analog) markedly reduced the P-selectin- enhanced adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized Fg (Fig. 6A) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 6B). In contrast, PD98059 (a MEK inhibitor) did not decrease the P-selectin enhanced adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized Fg (Fig. 6A) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, PTX (a GPCR inhibitor) had no inhibitory effect on the P-selectin-elicited adhesion of neutrophils to Fg and ICAM-1, even though it potently prevented the IL-8 and platelet activating factor (PAF)-induced adhesion of neutrophils to Fg (Fig. 6C). Our findings indicate that Src kinase-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, but not GPCRs, is essential for the P-selectin induced αMβ2 activation.

Figure 6.

The Src kinase inhibitor attenuates αMβ2-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Neutrophils were incubated with hIgG, P-Rg, IL-8 or PAF and then added to the wells immobilized with Fg (A and C) and ICAM-1 (B). For inhibition experiments, neutrophils were preincubated with IB4 (a leukocyte adhesion blocking mAb to CD18), DMSO, PD98059 (a MAPK inhibitor), PP2 (a Src kinase inhibitor), daidzein (a structural inactive analog for genistein), genistein (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) or PTX (a GPCR inhibitor). The cell binding assay was performed same as described in Figure 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the bound cells determined in triplicate measurements of three separate experiments. **p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05

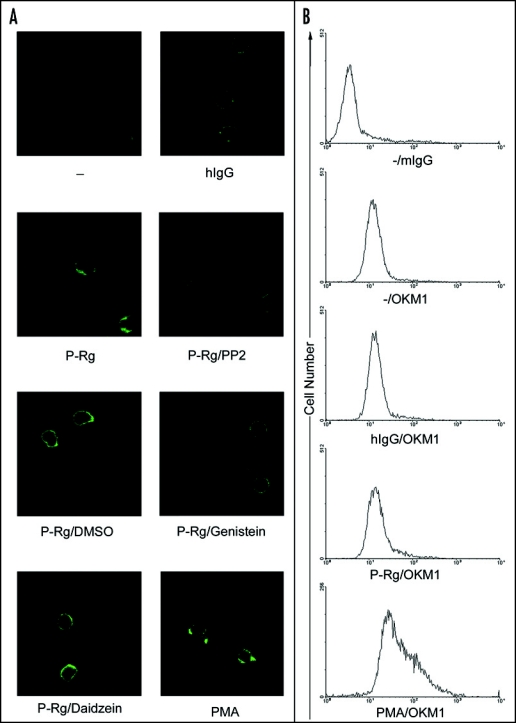

Cell-surface clustering of αMβ2.

As integrin clustering increased their ligand binding avidities, we also explored whether engagement and cross-linking of PSGL-1 by P-selectin could trigger αMβ2 clustering on the cell-surface of neutrophils. Using OKM1 (a mAb to αM subunit) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and laser scanning confocal microscopy, we found that compared to the buffer and human IgG controls, P-selectin Rg clearly induced a moderate clustering of αMβ2, whereas PMA triggered a dramatic clustering of αMβ2 on the cell surface of human neutrophils (Fig. 7A). Notably, PP2 and genistein, but not daidzein, prevented the P-selectin Rg-induced clustering of αMβ2, indicating that tyrosine phosphorylation-mediated integrin clustering is responsible for αMβ2 activation induced by P-selectin. Notably, P-selectin Rg did not increase the cell-surface expression of αMβ2 as compared to PMA (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

P-selectin triggers αMβ2 clustering. Neutrophils were preincubated with buffer (-), hIgG, P-Rg or PMA. For inhibition experiments, cells were preincubated with P-Rg in the presence of DMSO, PP2, genistein or daidzein. They were then incubated with OKM-1, a mAb specific for αM subunit followed by the FITC-conjugated anti-mIgG Ab. After washing twice, they were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, plated on a glass cover slip and observed under a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope (A). The cell binding assay was performed same as described in Figure 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. values of the bound cells determined in triplicate measurements of three separate experiments. **p < 0.01. In parallel, neutrophils were incubated with buffer (-), hIgG, P-Rg or PMA followed by mIgG and OKM1. Samples were further incubated with the FITC-conjugated anti-mIgG Ab. After washing twice, they were analyzed by FACS analysis.

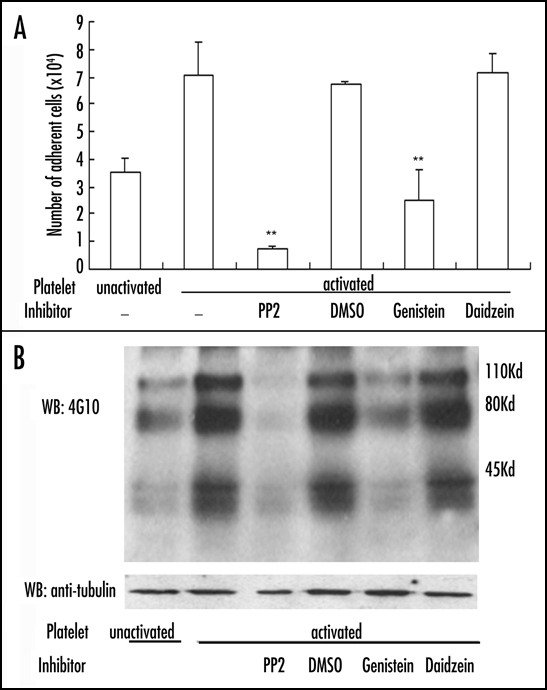

Thrombin-stimulated platelets activate αMβ2 in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner.

To obtain the cellular evidence for our findings described above, we tested whether the binding of activated platelets that express P-selectin to neutrophil PSGL-1 induces αMβ2 activation. As expected, incubation with thrombin activated human platelets, but not quiescent human platelets, increased adhesion of human neutrophils to immobilized Fg, which was inhibited by PP2 and genistein (Fig. 8A). Activated platelets also induced tyrosine phosphorylation of various cellular proteins with their relative molecular masses at ∼110, ∼80 and ∼40 kDa, all of which were detected by 4G10, a mAb specific for protein tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 8B upper panel). As expected, PP2 and genistein, but not daidzein, potently prevented tyrosine phosphorylation of these neutrophil proteins. The immunoblotting of α-tubulin was used as the sample loading controls (Fig. 8B lower panel). These data demonstrate that activated platelets can indeed induce αMβ2 activation in a Src kinase-dependent mechanism.

Figure 8.

Activated platelets prime αMβ2 and elicit tyrosine phosphorylation. Thrombin-activated human platelets were incubated with human neutrophils, prior to transferring them to the wells immobilized with Fg (A). Alternatively, they were lysed and tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by 4G10 (B). The results are representative of three separate experiments. **p < 0.01.

Statistical analyses.

To determine statistical significance, student's unpaired t-test was used for comparison between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

The significance of signaling events at the downstream of cadherin and integrin families of cell adhesion molecules has been well appreciated and investigated.23 For example, β-catenin interacts directly with the cytoplasmic domains of E-cadherin. When released, β-catenin in the cytoplasm undergoes phosphorylation and degradation in the proteosomes. Alternatively, it enters the nucleus and induces the promoter activity of LEF/TCF (lymphoid enhancer factor/T-cell factor) for Wnt signaling, which is essential for development, differentiation and maintenance of epithelial cells. Pathological activation of Wnt signaling leads to tumorigenesis, such as colon carcinoma and many other cancers of epithelial origin.23–25 However, whether selectins and their cognate glycoprotein ligands exert cellular signaling and whether these signaling events are important in leukocyte recruitment remain elusive thus far.26 In this regard, P-selectin has been shown to induce NFκB activation in monocytes and to activate spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) in leukocytes.27–28

In the present study, we have shown that engagement and cross- linking of PSGL-1 by P-selectin induces activation of leukocyte integrins, such as αMβ2. In addition to recombinant P-selectin receptor-globulin and the anti-PSGL-1 mAb, native platelet P-selectin and thrombin-stimulated platelets both trigger αMβ2 activation, attesting to the biological relevance of P-selectin induced integrin activation in recruitment of leukocytes during inflammatory responses, which is consistent with previous report.29–32 In sharp contrast with GPCR-dependent integrin activation elicited by cytokines and chemokines, P-selectin activates αMβ2 in a mechanism that is dependent on Src kinase-mediated protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Our results thus provide evidence for the P-selectin-induced, Src kinase-dependent signaling for integrin activation, which activates integrins synergistically with the cytokine and chemokines-induced, GPCR-dependent signaling for maximal adhesion of leukocytes in host defense and innate immunity.

Cytokines, chemokines and chemoattractants, such as PAF and IL-8 synthesized by vascular endothelial cells, bind to receptors that span the membrane seven times on the cell-surface of leukocytes, which couple to G proteins and induce “inside-outside” signaling pathways that impinge on integrin cytoplasmic domains and activate integrin adhesiveness.1,14 This process plays an important role on neutrophil localization in the vasculature upon inflammatory challenges. Other inflammatory stimuli including C5a, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) and PMA also trigger the functional activation of β2-integrins.21 As the binding of P-selectin to PSGL-1 stimulates secretion of IL-8 in human neutrophils,16 the possibility for induction of IL-8 that indirectly activates αMβ2 upon cross-linking of PSGL-1 exists. However, this hypothesis is apparently challenged by our experimental data: first, a neutralizing P-selectin mAb prevents enhanced adhesion of neutrophils that were preincubated with the supernatant from the P-selectin Rg treated cells; second, PMA or P-selectin (8 h) induces <2 ng/ml IL-8 secretion in eight hours, whereas >50 ng/ml IL-8 is required for αMβ2 activation in 25 minutes; and third, a blocking IL-8 mAb does not affect P-selectin-induced adhesion of neutrophils to Fg. These results collectively argue for the direct action of P-selectin on integrin activation.

Engagement of PSGL-1 reportedly enhances tyrosine phosphorylation and activates MAP kinases, ERK-1 and ERK-2, through MEK in human neutrophils.16 However, their functional roles are unknown. The finding that PP2 (a Src kinase inhibitor), but not PD98059 (a MEK inhibitor), attenuates P-selectin-induced adhesion of neutrophils to immobilized fibrinogen and ICAM-1 indicates that protein tyrosine phosphorylation by Src kinases, but not by MAP kinase ERK, critically participates in the signal transduction pathway at the downstream of PSGL-1 for αMβ2 activation. Notably, compared to their effects on neutrophil adhesion to fibrinogen, PP2 and genistein are apparently less potent for inhibition of P-selectin-induced neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1, which may result from a difference in Fg and ICAM-1 ligand density.33 Importantly, our results of Src kinases in P-selectin-induced integrin activation is fully consistent with the recent report28 of Src kinases in E-selectin-triggered activation of integrins, demonstrating the central role of Src kinases in integrin activation elicited by selectins in leukocyte recruitment during inflammation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (30421005, 30623003, 30400245 and 30630036), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2002CB513006, 2006CB943902, 2006AA02Z169, 2007CB-947100 and 2007CB914501), the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-YW-R-67 and KJCX2-YW-H08), the Shanghai Municipal Commission for Science and Technology (04JC14078, 06DZ22032, 055407035 and 058014578) and the National Institute of Health (RO1AI064743).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- Fg

fibrinogen

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- IL-8

interleukine-8

- ICAM-1

intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- PAF

platelet activating factor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4)

- PMA

phorbol myristate acetate

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- Rg

receptor-globulin

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/4984

References

- 1.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: The multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence MB, Springer TA. Leukocytes roll on a selectin at physiologic flow rates: Distinction from and prerequisite for adhesion through integrins. Cell. 1991;65:859–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90393-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen SD. Cell surface lectins in the immune system. Semin Immunol. 1993;5:237–247. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furie B, Furie BC, Flaumenhaft R. A journey with platelet P-selectin: The molecular basis of granule secretion, signalling and cell adhesion. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEver RP. Selectins: Lectins that initiate cell adhesion under flow. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng JG, Bevilacqua MP, Moore KL, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Kim JM, Bliss GA, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP. Rapid neutrophil adhesion to activated endothelium mediated by GMP-140. Nature. 1990;343:757–760. doi: 10.1038/343757a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma L, Raycroft L, Asa D, Anderson DC, Geng JG. A sialoglycoprotein from human leukocytes functions as a ligand for P-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27739–27746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Languino LR. Fibrinogen mediates leukocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium through an ICAM-1 dependent pathway. Cell. 1993;73:1423–1434. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90367-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sriramarao P, Languino LR, Altieri DC. Fibrinogen mediates leukocyte- endothelium bridging in vivo at low shear forces. Blood. 1996;88:3416–3423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Languino LR, Duperrray A, Joganic KJ, Fornaro M, Thornton GB, Altieri DC. Regulation of leukocyte-endothelium interaction and leukocyte transendothelial migration by intercellular adhesion molecule 1-fibrinogen recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1505–1509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenzuela R, Shainoff JR, DiBello PM, Urbanic DA, Anderson JM, Matsueda GR, Kudryk BJ. Immunoelectrophoretic and immunohistochemical characterizations of fibrinogen derivatives in atherosclerotic aortic intimas and vascular prosthesis pseudo-intimas. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:861–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, Helfrich MH, Horton MA, Feigen LP, Lefkowith JB. Fibrinogen mediates platelet-polymorphonuclear leukocyte cooperation during immune-complex glomerulonephritis in rats. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:928–996. doi: 10.1172/JCI117459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuijper PH, Gallardo Tores HI, Lammers JW, Sixma JJ, Koenderman L, Zwaginga JJ. Platelet associated fibrinogen and ICAM-2 induce firm adhesion of neutrophils under flow conditions. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorant DE, Patel KD, McIntyre TM, McEver RP, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Coexpression of GMP-140 and PAF by endothelium stimulated by histamine or thrombin: A juxtacrine system for adhesion and activation of neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:223–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorant DE, Topham MK, Whatley RE, McEver RP, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Inflammatory roles of P-selectin. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:559–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI116623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidari KI, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP. Engagement of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 enhances tyrosine phosphorylation and activates mitogen-activated protein kinases in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28750–28756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkalow FJ, Barkalow KL, Mayadas TN. Dimerization of P-selectin in platelets and endothelial cells. Blood. 2000;96:3070–3077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asa D, Raycroft L, Ma L, Aeed PA, Kaytes PS, Elhammer AP, Geng JG. The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand functions as a common human leukocyte ligand for P- and E-selectins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11662–11670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JG, Geng JG. Affinity and kinetics of P-selectin binding to heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:309–316. doi: 10.1160/TH03-01-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Croce K, Freedman SJ, Furie BC, Furie B. Interaction between soluble P-selectin and soluble P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1: Equilibrium binding analysis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16472–16480. doi: 10.1021/bi981341g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan-Qing Ma, Plow Edward F, Jian-Guo Geng. P-selectin binding to P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 induces an intermediate state of αMβ2 activation and acts cooperatively with extracellular stimuli to support maximal adhesion of human neutrophils. Blood. 2004;104:2549–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, Geng JG. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by Slit-Robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking Robo activity. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conacci-Sorrell Maralice, Jacob Zhurinsky, Avri Ben-Ze'ev. The cadherin-catenin adhesion system in signaling and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:987–991. doi: 10.1172/JCI15429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brembeck Felix H, Rosa'rio Marta, Birchmeier Walter. Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of β-catenin. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2006;16:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson WJ, Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, β-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarbock A, Lowell CA, Ley K. Spleen tyrosine kinase Syk is necessary for E-selectin-induced alpha(L)beta(2) integrin-mediated rolling on intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Immunity. 2007;26:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weyrich AS, McIntyre TM, McEver RP, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Monocyte tethering by P-selectin regulates monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion: Signal integration and NF-kappa B translocation. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2297–2303. doi: 10.1172/JCI117921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urzainqui A, Serrador JM, Viedma F, Yáñez-Mó M, Rodríguez A, Corbí AL, Alonso-Lebrero JL, Luque A, Deckert M, Vázquez J, Sánchez-Madrid F. ITAM-based interaction of ERM proteins with Syk mediates signaling by the leukocyte adhesion receptor PSGL-1. Immunity. 2002;17:401–412. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evangelista V, Manarini S, Rotondo S, Martelli N, Polischuk R, McGregor JL, de Gaetano G, Cerletti C. Platelet/polymorphonuclear leukocyte interaction in dynamic conditions: Evidence of adhesion cascade and cross talk between P-selectin and the beta 2 integrin CD11b/CD18. Blood. 1996;88:4183–4194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evangelista V, Manarini S, Sideri R, Rotondo S, Martelli N, Piccoli A, Totani L, Piccardoni P, Vestweber D, de Gaetano G, Cerletti C. Platelet/polymorphonuclear leukocyte interaction: P-selectin triggers protein-tyrosine phosphorylationdependent CD11b/CD18 adhesion: Role of PSGL-1 as a signaling molecule. Blood. 1999;93:876–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piccardoni P, Sideri R, Manarini S, Piccoli A, Martelli N, de Gaetano G, Cerletti C, Evangelista V. Platelet/polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion: A new role for SRC kinases in Mac-1 adhesive function triggered by P-selectin. Blood. 2001;98:108–116. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanks JE, Moll T, Eytner R, Vestweber D. Stimulation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 on mouse neutrophils activates beta 2-integrin mediated cell attachment to ICAM-1. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:433–443. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<433::AID-IMMU433>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giagulli Cinzia, Scarpini Elio, Ottoboni Linda, Narumiya Shuh, Butcher Eugene C, Constantin Gabriela, Laudanna Carlo. RhoA and ζ PKC control distinct modalities of LFA-1 activation by chemokines: Critical role of LFA-1 affinity triggering in lymphocyte in vivo homing. Immunity. 2004;20:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]