Abstract

Canonical WNT signals play an important role in hair follicle development. In addition to being crucial for epidermal appendage initiation, they control the interfollicular spacing pattern and contribute to the spatial orientation and largely parallel alignment of hair follicles. However, owing to the complexity of canonical WNT signalling and its interconnections with other pathways, many details of hair follicle formation await further clarification. Here, we discuss the recently suggested reaction-diffusion (RD) mechanism of spatial hair follicle arrangement in the light of yet unpublished data and conclusions. They clearly demonstrate that the observed hair follicle clustering in dickkopf (DKK) transgenic mice cannot be explained by any trivial process caused by protein overexpression, thereby further supporting our model of hair follicle spacing. Furthermore, we suggest future experiments to challenge the RD model of spatial follicle arrangement.

Key Words: hair follicle, pattern formation, WNT, DKK, KRM, LRP

In order to stimulate the canonical WNT signalling pathway, members of the WNT protein family have to bind to their cognate Frizzled receptors as well as to a co-receptor encoded by Lrp5 and 6, respectively.1–3 Pathway activation is competitively inhibited by soluble WNT binding proteins such as secreted frizzled related proteins (SFRPs).4,5 Moreover, members of the DKK family bind non-competitively to LRPs;6,7 simultaneous interaction with Kremen (KRM) 1 or 2 causes depletion of WNT co-receptors from the cell surface, thereby inhibiting canonical WNT signals.8

Based on previous findings concerning the importance of WNT signalling in hair follicle initiation and orientation,9,10 we recently hypothesised that the pathway may also have an essential role in the spatial arrangement of follicles. Using a combined experimental and computational modelling approach, we provided evidence for WNTs and DKKs controlling interfollicular spacing through a reaction-diffusion mechanism (Fig. 1).11 By confirming the prediction of hair follicle clustering in the presence of moderate DKK overexpression, we demonstrated the biological implementation of a fundamental principle of pattern formation the mathematical basis of which has been described by Alan Turing in the 1950s.12

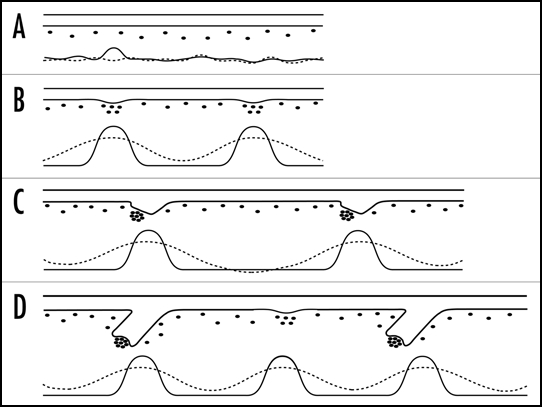

Figure 1.

Schematic of early hair follicle development in mouse and the hypothesised distribution of WNTs and DKKs as the critical regulators of interfollicular spacing. According to the RD hypothesis of Alan Turing, patterning starts with an almost even distribution of activator and inhibitor (solid and dashed lines, respectively) (A, bottom). Transferring the model to murine hair follicle morphogenesis, this molecular pattern is associated with a morphologically unstructured epidermis (A, top); (the underlying dermis is indicated by black spots). Of note, WNTs and DKKs were recently suggested to represent an activator/inhibitor pair in follicle development. In the RD model, small fluctuations in the initially even protein distribution are enhanced and, eventually, give rise to a distinct and stable pattern of activator and inhibitor distribution (B, bottom). This is mainly achieved by an activator controlling expression of its own as well of the inhibitor, an inhibitor antagonising the activator's action, and an increased mobility of the inhibitor as compared to the activator. Although protein distribution in the developing skin is still hypothetical, the predicted pattern could control hair follicle morphogenesis, the first sign of which are epithelial thickenings (B, top). They stimulate the formation of dermal condensates which become dermal papillae later on. Of note, interfollicular spacing is solely determined by the parameters of the underlying RD mechanism. Hence, upon embryo growth, areas in between previously formed follicles again become capable of hair follicle formation owing to local protein levels (C). While the Turing model cannot describe this transitional state, it clearly predicts the formation of new follicles after enlargement of the interfollicular space (D); without changing the underlying parameters, the RD mechanism generates a fixed spacing pattern. Indeed, hair follicle development in mouse does occur by consecutive inductive waves.

Unexpectedly, DKK2 was capable of stimulating the WNT pathway in the absence of Krm2 expression.13 As discussed by Stark et al., this finding raises the possibility that transgenic overexpression of Dkk2 in our Foxn1::Dkk2 mice may directly activate the canonical WNT pathway.14 Thus, since stabilised β-catenin is sufficient for follicle formation,15 new appendages may be initiated adjacent to previously formed, Dkk2 expressing follicles, if their neighborhood lacks KRM protein.

Indeed, during early hair follicle development, interfollicular epidermis shows only weak Krm2 expression as compared to follicle buds (Fig. 2). Moreover, at more advanced stages, the distal part of emerging follicles may even lack any Krm2 gene activity. However, although Krm1 is also predominantly expressed in the developing hair bulb, moderate gene activity is found throughout the epidermis and the distal part of hair follicles (Fig. 3). Hence, developing follicles and their neighborhood do not represent a KRM-negative compartment. As a consequence, hair follicle induction by DKK2-mediated stimulation of the canonical WNT pathway is very unlikely.

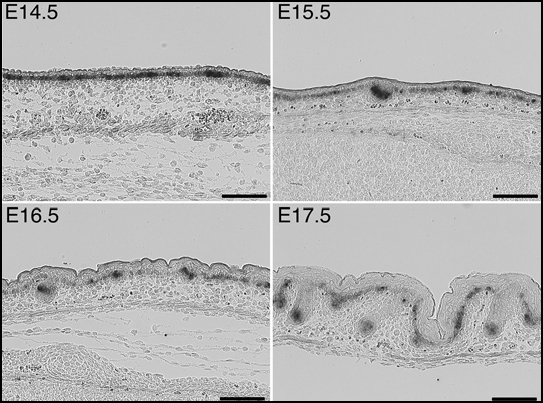

Figure 2.

Expression of Krm2 during early hair follicle development, demonstrated by non-radioactive in situ hybridisation. Bars, 100 µm.

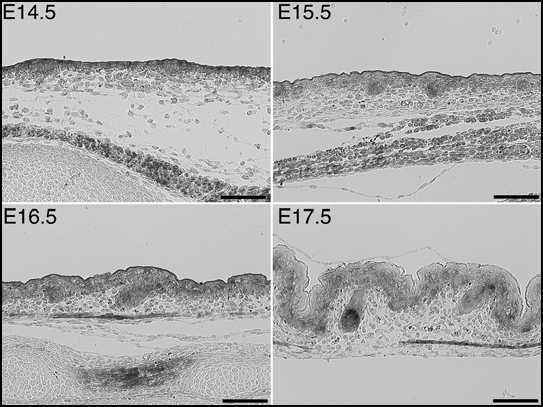

Figure 3.

Expression of Krm1 during early hair follicle development, demonstrated by non-radioactive in situ hybridisation. Bars, 100 µm.

In contrast to DKK2, DKK1 is unable to stimulate the canonical WNT pathway.16,17 This difference could be attributed to the amino-terminal domain. To investigate whether transgenic DKK2 may cause hair follicle clustering just by pathway activation, we generated Foxn1::Dkk1 transgenic mice. However, they showed essentially the same phenotype as Foxn1::Dkk2 animals.11 Moreover, transgenic mice expressing amino-terminally truncated DKK1 protein were largely indistinguishable from Foxn1::Dkk1 animals instead of showing an enhanced patterning abnormality (data not shown).

If direct stimulation of the canonical WNT signalling pathway by transgenic DKKs would be responsible for the severely altered spatial arrangement of hair follicles, increasing transgene expression should at least preserve or even enhance hair follicle clustering, while the distances between clusters may increase. However, mice with particularly strong Dkk2 transgene expression did not show hair follicle clusters but single, well-developed follicles with large interfollicular distances.11

In summary, our data do strongly argue against hair follicle clustering in transgenic mice by DKK-mediated activation of the WNT pathway. By contrast, all data are in line with the recently suggested RD model of hair follicle spacing.

Nevertheless, several questions remain to be answered. First, the identity of the WNT protein(s) involved in interfollicular patterning is unknown. Second, the contribution of the inhibitors DKK1 and DKK4 both of which are expressed during hair follicle initiation is still a matter of debate. In the light of multiple WNTs being expressed during early hair follicle morphogenesis,18 some redundancy appears to be likely. Hence, the effects of single gene knockouts may be limited and transgenic approaches with their intrinsic capability of dramatically changing overall WNT levels may be favourable to challenge the RD model and to identify the WNT family members that are involved in the patterning process. Likewise, gene inactivation of either Dkk1 or Dkk4 would be insufficient to provide further support for our model. In principle, the inhibitor(s) may be crucial for follicle formation while they are not involved in the interfollicular patterning process. By contrast, experimentally lowering the inhibitors' mobility should unequivocally support or disprove the proposed mechanism of hair follicle spacing. According to the underlying mathematical model, it should dramatically affect patterning in the presence of normal levels of functional protein.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/5073

References

- 1.Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–535. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinson KI, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery BJ, Skarnes WC. An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature. 2000;407:535–538. doi: 10.1038/35035124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wehrli M, Dougan ST, Caldwell K, O'Keefe L, Schwartz S, Vaizel-Ohayon D, Schejter E, Tomlinson A, DiNardo S. Arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature. 2000;407:527–530. doi: 10.1038/35035110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rattner A, Hsieh JC, Smallwood PM, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nathans J. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis S, Aikawa M, Szeto W, d'Amore PA, Papkoff J. A secreted frizzled related protein, FrzA, selectively associates with Wnt-1 protein and regulates wnt-1 signaling. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3815–3820. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA. Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:683–686. doi: 10.1038/35083081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature. 2001;411:321–325. doi: 10.1038/35077108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao B, Wu W, Davidson G, Marhold J, Li M, Mechler BM, Delius H, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Walter C, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2002;417:664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo N, Hawkins C, Nathans J. Frizzled6 controls hair patterning in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9277–9281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402802101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sick S, Reinker S, Timmer J, Schlake T. WNT and DKK determine hair follicle spacing through a reaction-diffusion mechanism. Science. 2006;314:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.1130088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turing A. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1952;237:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao B, Niehrs C. Kremen2 modulates Dickkopf2 activity during Wnt/LRP6 signaling. Gene. 2003;302:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark J, Andl T, Millar SE. Hairy math: Insights into hair-follicle spacing and orientation. Cell. 2007;128:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gat U, DasGupta R, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. De novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair tumors in mice expressing a truncated β-catenin in skin. Cell. 1998;95:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brott BK, Sokol SY. Regulation of Wnt/LRP signaling by distinct domains of Dickkopf proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6100–6110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6100-6110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Mao J, Sun L, Liu W, Wu D. Second cysteine-rich domain of Dickkopf-2 activates canonical Wnt signaling pathway via LRP-6 independently of dishevelled. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5977–5981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy S, Andl T, Bagasra A, Lu MM, Epstein DJ, Morrisey EE, Millar SE. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]