Abstract

Cleptoparasitic or cuckoo bees lay their eggs in nests of other bees, and the parasitic larvae feed the food that had been provided for the host larvae. Nothing is known about the specific signals used by the cuckoo bees for host nest finding, but previous studies have shown that olfactory cues originating from the host bee alone, or the host bee and the larval provision are essential. Here, I compared by using gas chromatography coupled to electroantennographic detection (GC-EAD) the antennal responses of the oligolectic oil-bee Macropis fulvipes and their cleptoparasite, Epeoloides coecutiens, to dynamic headspace scent samples of Lysimachia punctata, a pollen and oil host of Macropis. Both bee species respond to some scent compounds emitted by L. punctata, and two compounds, which were also found in scent samples collected from a Macropis nest entrance, elicited clear signals in the antennae of both species. These compounds may not only play a role for host plant detection by Macropis, but also for host nest detection by Epeoloides. I hypothesise that oligolectic bees and their cleptoparasites use the same compounds for host plant and host nest detection, respectively.

Key words: Macropis fulvipes, Epeoloides coecutiens, Lysimachia punctata, oligolectic oil-bee, floral scent, dynamic headspace, GC-EAD, cuckoo bee, host nest finding

Bees are the most important animal pollinators worldwide, and guarantee sexual reproduction of many plant species.1,2 This is especially true for female bees, which collect pollen and mostly nectar for their larvae and frequently visit flowers. For finding and detection of suitable flowers, bees are known to use, besides optical cues,3,4 especially olfactory signals.5–8 However, c. 20% of bees do not collect pollen for their larvae by their own, but enter nests of host bees and lay eggs into the broodcells.1,9 The parasitic larvae subsequently feed the food that had been provided for the host larvae. These so called cuckoo or cleptoparasitic bees can be generalistic, indicating that they use species of several other bee groups as host, whereas others can be highly specialized, laying eggs in cells of only few host species.1 Until now little is known about the cues used by the cuckoo bees for finding host nests. Nevertheless, Cane10 and Schindler11 demonstrated that parasitic Nomada bees use primarily visual cues of the nest entrance holes for finding possible nests, and olfactory cues for detection of suitable host nests. The chemical cues used by the cleptoparasites originate from the host bee10,11 and also pollen,10 the main larval provision. In most bee species, pollen is mixed together with nectar as larval provision, and both floral resources are known to emit volatiles.12,13 It is unknown, whether cuckoo bees in search for host nests also use volatiles originating from nectar. While the odours of the host bee used as signal by the cleptoparasites, e.g., cuticiular hydrocarbons and glandular secretions, are often species-specific,14 the chemical cues from the larval provision may just indicate the presence of pollen in the nest without more specifity. As a consequence cuckoo bees could use species-specific host odours to detect nests of a suitable host, and odours released from the larval provision could indicate to them that broodcells are foraged. However, especially those cuckoo bees with oligolectic hosts foraging pollen only on few closely related plant species,1 may also use the olfactory signals from host broodcell supplies as more specific cue for host nest detection. Thus the same signal from certain flowers may be used for different informations: for the host bee for host plant and for the cuckoo bee for host nest detection.

In this concern I tested oligolectic Macropis (Melittidae, Melittinae) and its specific cuckoo bee, Epeoloides (Apidae, Apinae) by using gas chromatography coupled to electroantennographic detection (GC-EAD) on floral scent of Lysimachia (Myrsinaceae). Macropis is highly specialized on Lysimachia, because it is not only collecting pollen from plants of this genus, but also floral oil. Both floral products are the only provision for the larvae.1,15 Recently, we have shown that the oil bee Macropis is strongly attracted to floral scent of its oil host Lysimachia though the compounds used for host plant finding are still unknown.7 Macropis is the only host of Epeoloides, and larvae of this cleptoparasite only feed on the Lysimachia pollen-oil mixture provided for the larvae of Macropis. Worldwide, there are only 2 species of this genus, one in North America and the other in Europe/Asia.1,16,17 I hypothesized that both bee species respond to specific Lysimachia compounds, which may be used for host plant as well as host nest detection.

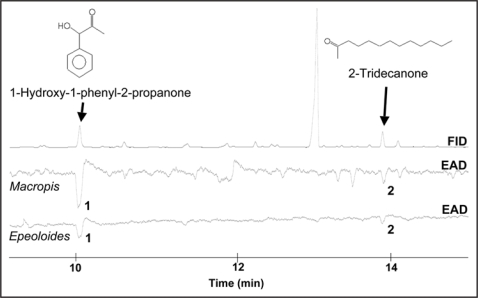

The measurements with M. fulvipes (F.) and E. coecutiens (F.) antennae demonstrate that both bees, host as well as cuckoo bee, respond to some scent compounds emitted by inflorescences of Lysimachia punctata L. (Fig. 1), a plant being an important pollen and oil source for M. fulvipes. Macropis responded to much more Lysimachia compounds compared to the cuckoo bee, however, two compounds elicited clear signals in the antennae of both bee species: the benzenoid 1-hydroxy-1-phenyl-2-propanone, and the fatty acid derivative 2-tridecanone. Interestingly, both compounds are also emitted from the floral oil of this plant,7 and both compounds were also detected in scent samples collected by dynamic headspace in the entrance of a Macropis nest (Dötterl, unpublished data). Therefore, an Epeoloides female being in search for a host nest can detect volatiles emitted from the provision of the host bee at the entrance of a bee nest, and may use these specific compounds for detection of a Macropis nest provisioned with Lysimachia pollen and oil.

Figure 1.

Coupled gas chromatographic and electroantennographic detection of a Lysimachia punctata headspace scent sample using antennae of a female oligolectic Macropis fulvipes and a female cleptoparasitic Epeoloides coecutiens bee. (1) 1-hydroxy-1-phenyl-2-propanone, (2) 2-tridecanone.

Present results show that an oligolectic oil-bee as well as its cleptoparasite detects volatiles originating from the host plant of the pollen collecting bee, and that oligolectic bees as well as their cuckoo bees may use the same specific signals for host plant and host nest finding, respectively. Biotests are now needed to test this hypothesis.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/5271

References

- 1.Michener CD. The Bees of the World. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neff JL, Simpson BB. Bees, pollination systems and plant diversity. In: Lasalle J, Gauld ID, editors. Hymenoptera and Biodiversity. Wallingford: CAB International; 1993. pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunau K, Maier EJ. Innate colour preferences of flower visitors. J Comp Physiol A. 1995;177:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chittka L, Kevan PG. Flower colour as advertisement. In: Dafni A, Kevan PG, Husband BC, editors. Practical Pollination Biology. Cambridge: Enviroquest, Ltd.; 2005. pp. 157–196. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobson HEM, Bergström G. The ecology and evolution of pollen odors. Plant Syst Evol. 2000;222:63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dötterl S, Füssel U, Jürgens A, Aas G. 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, a floral scent compound in willows that attracts an oligolectic bee. J Chem Ecol. 2005;31:2993–2998. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-9152-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dötterl S, Schäffler I. Flower scent of floral-oil producing Lysimachia punctata as cue for the oil-bee Macropis fulvipes. J Chem Ecol. 2007;33:441–445. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell AD, Alarcón R. Osmia bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) can detect nectar-rewarding flowers using olfactory cues. Anim Behav. 2007;74:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wcislo WT. The roles of seasonality, host synchrony, and behaviour in the evolutions and distributions of nest parasites in Hymenoptera (Insecta), with special reference to bees (Apoidea) Biological Review. 1981;62:515–543. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cane JH. Olfactory evaluation of Andrena host nest suitability by kleptoparasitic Nomada bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) Anim Behav. 1983;31:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schindler M. Biologie kleptoparasitischer Bienen und ihrer Wirte (Hymenoptera, Apiformes) Bonn: Department of Agricultural Zoology and Apidology, University of Bonn; 2004. (Ger). PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jürgens A, Dötterl S. Chemical composition of anther volatiles in Ranunculaceae: Genera-specific profiles in Anemone, Aquilegia, Caltha, Pulsatilla, Ranunculus, and Trollius species. Am J Bot. 2004;91:1969–1980. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.12.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raguso RA. Why are some floral nectars scented? Ecology. 2004;85:1486–1494. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayasse M, Paxton RJ, Tengö J. Mating behavior and chemical communication in the order Hymenoptera. Ann Rev Entomol. 2001;46:31–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel S. Ölblumen und ölsammelnde Bienen, Zweite Folge: Lysimachia und Macropis. Mainz, Stuttgart: Akademie der Wissenschaft und der Literatur, Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH; 1986. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogusch P. Biology of the cleptoparasitic bee Epeoloides coecutiens (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Osirini) J Kans Entomol Soc. 2005;78:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ascher JS. Epeoloides pilosula (Cresson, 1878) [a cleptoparasite of Macropis oil bees] (Hymenoptera: [Apoidea:] Apinae: Osirini) In: Shepherd MD, Vaughan DM, Black SH, editors. Red List of Pollinator Insects of Norh America, CD-ROM Version 1 (May 2005) Portland: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation; 2005. [Google Scholar]