Abstract

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) associations have strikingly constant structural and functional features, irrespectively of the organisms involved. This suggests the existence of common genetic and molecular determinants. one of the most important characteristics of AMs is the coating of intracellular hyphae by a proliferation of the plant plasma membrane, which always segregates the fungus in an apoplastic interface. This process of intracellular accommodation causes a dramatic reorganization in the host cell cytoplasm, which reaches its peak with the development of the so-called prepenetration apparatus (PPA), a specialised aggregation of organelles described in epidermal cells and predicting fungal development within the cell lumen. We have recently correlated PPA development with the significant regulation of 15 Medicago truncatula genes. Among these, a nodulin-like and an expansin-like sequence are good candidates as molecular markers of epidermal cell responses to AM contact. our results also suggest a novel role for the kinase DMI3 in enhancing the upregulation of these two genes and downregulating defence-related genes such as the Avr9/Cf-9 rapidly elicited protein 264. We here comment on these recent findings and their possible outcomes.

Key Words: arbuscular mycorrhiza, colonization process, prepenetration apparatus, epidermal cells, transcriptome analysis

Land plants share an ancient, 450 million-year-old, coevolutionary history with a few soil fungi, with whom they have established a mutualistic association, called arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM). Both partners benefit from nutrient transfers,1 as the obligate biotrophic fungi belonging to the Glomeromycota2 facilitate the uptake of nutrients such as phosphate by plants, while plants provide carbon sources to the fungi required to complete their life cycle.

The ubiquitous nature of AM associations and their constant structural and functional features, strongly suggest the existence of common molecular and genetic determinants across different plant taxa, ranging from liverworts to ferns and angiosperms. A landmark of AM associations is the occurrence of an apoplastic interface between the two organisms provided by a membrane of host origin around the intracellular fungal hyphae. This interface allows profound molecular, biochemical and physiological readjustments in the plant cell in order to accommodate its fungal partner.3 Biologists have long tried to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms which regulate this intimate association. Recently, Genre et al.4 targeted plant cellular events during initial colonisation by the AM fungus. They described how epidermal cells assemble a transcellular structure right below the fungal appressorium, a few hours before host cell penetration. Upon appressorium formation, a precise succession of processes, coordinated by the nucleus, leads to the formation of the so-called prepenetration apparatus (PPA). This appears as a cytoplasmic column containing microtubule and microfilament bundles, very dense endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cisternae and a central membrane thread. Only after the column has been formed, the fungus enters the cell and grows across it, suggesting on the one hand that the host plant has a major control over fungal development, and on the other hand that PPA is directly involved in the construction of the interface compartment. Many questions remain to be answered in order to understand PPA formation: (1) how does the plant perceive local fungal signals, (2) how does the plant distinguish between a friend and a foe, (3) is the PPA exclusively present in epidermal cells or is it also produced in cortical cells, (4) what are the molecular events activated in the epidermal cell during PPA assembly.

Since the activation of at least one gene (MtENOD11) had already been associated with PPA formation, we investigated whether additional transcripts could be associated with PPA development. For that purpose, we worked with the same experimental material used before (in vitro cultures of Medicago truncatula-transformed roots expressing GFP: HDEL, inoculated with the AM fungus Gigaspora margarita), making use of the PPA as a cellular marker to identify the root areas actively responding to early fungal contact. This experimental system allowed us to follow PPA formation beneath fungal appressoria in vivo, under a confocal microscope. To avoid transcript dilution, one of the major problems in transcriptome analysis of AM roots,5 we developed a targeted sampling procedure where we collected short M. truncatula root fragments centered around the PPAs. They were localized in living roots by means of confocal live cell imaging of GFP-tagged ER.6 Comparable fragments were collected from non-inoculated roots. From these material a SSH library was constructed and differentially expressed genes were identified. Differential expression was confirmed by reverse northern blot analysis for 15 genes. Their expression profile was analysed by real time PCR and compared with that from non-inoculated M. truncatula as well as from dmi3-1 mutant plants, lacking a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, that do not establish mycorrhizas7 and never produce PPAs.4 The experiments demonstrated that at least two novel genes could be suggested as good markers of PPA formation. They are significantly upregulated in the root fragments containing such structures, when compared with the control and the dmi3-1 mutant. The mRNA of one of them, the expansin-like protein, was preferentially detected in epidermal cells following fungal contact, using in situ hybridization. As a second important finding, an Avr9/Cf-9 rapidly elicited protein 264, was found to be upregulated in the dmi3-1 mutant plant, suggesting that this gene is under negative control of DMI3 which opens new vistas on the mechanisms controlling compatibility in AM interactions.

Whole Root Versus Selected Fragment Transcriptome Profiling of AM: What is New?

The development of molecular tools has recently allowed the acquisition of large transcriptomic profile data sets of AM8–11 and control roots and shoots.12 However, AM expression profiles are so far affected by a few, so far unsolved, spatial and temporal issues. Firts, sampling the whole root system causes a dilution effect, since the number of colonized cells is often quite limited when compared to the whole root cell population, especially when early colonization stages are investigated. According to Küster et al.5 this seriously hampers the detection of genes that are locally expressed or undergo minor transcriptional changes. Secondly, colonization events are not synchronous. According to Genre et al.,4 epidermis colonization is completed in less than ten hours, while the development of functional arbuscules takes an additional one to two days.13 After four to five days arbuscules start to collapse,3 but neighboring cells are ready to host new infections. Therefore, expression profiles within time frames defined in terms of days post inoculation do not correspond to clearly defined steps during the plant-fungus interaction. Even greater variations in the extension of root colonization have been reported.14 These observations highlight the need for a cellular marker to provide temporal and spatial reference points.

To our knowledge, PPA is the earliest plant cellular marker available, since it identifies epidermal cells that are about to be colonized. Through a combination of cell biology and molecular tools we have identified plant genes that are differentially expressed during PPA development.6 They include genes involved in cell wall modification, such as the above-mentioned expansin-like gene, as well as a cellulose synthase, highly expressed also during later stages (Siciliano V, unpublished and ref. 15). Genes related to membrane dynamics and secretion events, like SNARE11 were also activated, confirming the hypothesis that the PPA may directly be involved in the interface compartment assembly. Plant cell wall molecules are known to be secreted in the space between the fungal wall and the perifungal membrane not only in arbusculated16 but also in epidermal cells.17 A long list of genes related to resistance, pathogenesis and defense signaling mechanisms were found, many of which confirm the results obtained in other investigations focussed on the early interaction.14 However, our sampling from WT and the dmi3-1 mutant lacking the DMI3 Ca/calmodulin-dependent kinase activity, has allowed us to correlate gene expression to specific points in time (0 and 48 hours after appressorium formation) and space (epidermal cells) during the infection process. The suppression of basal defense-related genes like ACRE264, possibly after the perception of a diffusible fungal factor or merely after physical contact with the appressorium, supports the hypothesis that plant-AM fungus compatibility requires basal defense responses to be kept under control similarly to what happens in compatible plant-pathogen interactions.

Another intriguing question that arises from these findings—assuming fungal signals are perceived by the plant—is how root cells share the task of setting up a functioning symbiotic root? Is the response cell type-dependent? Can we hypothesize that epidermal cells are mostly involved in recognition mechanisms and cortical cells in the symbiosis functioning? Recent data based on RNAi plants and on the expression analysis of laser-dissected cells,18,19 suggest that this hypothesis might easily be tested in a near future.

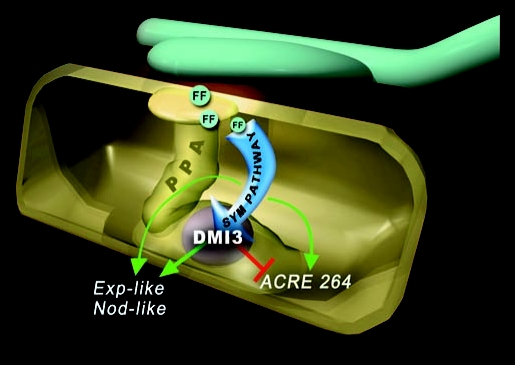

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the prepenetration apparatus (PPA) molecular background, as deduced from the presented results. In the presence of an AM fungal contact and after the perception of a putative fungal factor (FF), Exp-like and Nod-like are weakly activated independent of DMI3, a key component of the SYM signalling pathway. DMI3 activity, by contrast, further upregulates Exp-like and Nod-like, represses ACRE264 and is required for PPA assembly.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Italian MIUR (Prin 2006; Cebiovem 2004–06), University of Torino (60% Project, 2004–06), and IPP-CNR (Biodiversity National Project) to P.B.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/4745

References

- 1.Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. London: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schüßler A, Schwarzott D, Walker C. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: Phylogeny and evolution. Mycol Res. 2001;105:1413–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonfante P. Anatomy and morphology. In: Powell CL, Bagyaraj DJ, editors. V. A. Mycorrhizas. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1984. pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genre A, Chabaud M, Timmers T, Bonfante P, Barker DG. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi elicit a novel intracellular apparatus in Medicago truncatula root epidermal cells before infection. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3489–3499. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Küster H, Vieweg MF, Manthey K, Baier MC, Hohnjec N, Perlick AM. Identification and expression regulation of symbiotically activated legume genes. Phytochemestry. 2007;68:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siciliano V, Genre A, Balestrini R, Cappellazzo G, DeWitt P, Bonfante P. Transcriptome analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal roots during development of the prepenetration apparatus. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1455–1466. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.097980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lévy J, Bres C, Geurts R, Chalhoub B, Kulikova O, Duc G, Journet EP, Ane JM, Lauber E, Bisseling T, et al. A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science. 2004;303:1361–1364. doi: 10.1126/science.1093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison MJ, Dewbre GR, Liu J. A phosphate transporter from Medicago truncatula involved in the acquisition of phosphate released by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2413–2429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wulf A, Manthey K, Doll J, Perlick AM, Linke B, Bekel T, Meyer F, Franken P, Küster H, Krajinski F. Transcriptional changes in response to arbuscular mycorrhiza development in the model plant Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16:306–314. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kistner C, Winzer T, Pitzschke A, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Webb J, et al. Seven Lotus japonicus genes required for transcriptional reprogramming of the root during fungal and bacterial symbiosis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2217–2229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohnjec N, Vieweg MF, Puhler A, Becker A, Küster H. Overlaps in the transcriptional profiles of Medicago truncatula roots inoculated with two different Glomus fungi provide insights into the genetic program activated during arbuscular mycorrhiza. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:1283–1301. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.056572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Maldonado-Mendoza I, Lopez-Meyer M, Cheung F, Town CD, Harrisom MJ. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is accompanied by local and systemic alterations in gene expression and an increase in disease resistance in the shoots. Plant J. 2007:529–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SE, Barker SJ, Zhu YG. Fast moves in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weidmann S, Sanchez L, Descombin J, Chatagnier O, Gianinazzi S, Gianinazzi-Pearson V. Fungal elicitation of signal transduction related plant genes precedes mycorrhiza establishment and requires the dmi3 gene in Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:1385–1393. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.12.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balestrini R, Lanfranco L. Fungal and plant gene expression in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mycorrhiza. 2006;16:509–524. doi: 10.1007/s00572-006-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonfante P. At the interface between mycorrhizal fungi and plants: The structural organization of cell wall, plasma membrane and cytoskeleton. In: Esser K, Hock B, editors. The Mycota IX. Berlín, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balestrini R, Hahn MG, Faccio A, Mendgen K, Bonfante P. Differential localization of carbohydrate epitopes in plant cell walls in the presence and absence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:203–213. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javot H, Varma Penmetsa R, Terzaghi N, Cook DR, Harrison MJ. A Medicago truncatula phosphate transporter indispensable for the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1720–1725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608136104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balestrini R, Gómez-Ariza J, Lanfranco L, Bonfante P. Laser microdissection reveals that transcripts for five plant and one fungal phosphate transporter genes are contemporaneously present in arbusculated cells. Mol Microbe Plant Interact. 2007;20:1055–1062. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-9-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]