Abstract

Receptor-like proteins (RLPs) are cell surface receptors that play important roles in various processes. In several plant species RLPs have been found to play a role in disease resistance, including the tomato Cf and Ve proteins and the apple HcrVf proteins that mediate resistance against the fungal pathogens Cladosporium fulvum, Verticillium spp., and Venturia inaequalis, respectively. The Arabidopsis genome contains 57 AtRLP genes. Two of these, CLV2 (AtRLP10) and TMM (AtRLP17), have well-characterized functions in meristem and stomatal development, respectively, while AtRLP52 is required for defense against powdery mildew. We recently reported the assembly of a genome-wide collection of T-DNA insertion lines for the Arabidopsis AtRLP genes. This collection was functionally analyzed with respect to plant growth, development and sensitivity to various stress responses including pathogen susceptibility. Only few new phenotypes were discovered; while AtRLP41 was found to mediate abscisic acid sensitivity, AtRLP30 (and possibly AtRLP18) was found to be required for full non-host resistance to a bacterial pathogen. Possibly, identification of novel phenotypes is obscured by functional redundancy. Therefore, RNA interference (RNAi) to target the expression of multiple AtRLP genes simultaneously was employed followed by functional analysis of the RNAi lines.

Key words: pathogen defense, development, redundancy, clavata, too many mouths, abiotic and biotic stress, RLP, abscisic acid, ABA

Receptor-like proteins (RLPs) are cell surface receptors that typically consist of an extracellular leucine-rich repeat (eLRR) domain, a single-pass transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmatic tail that lacks obvious motifs for intracellular signaling except for the putative endocytosis motif found in some members.1–3 In several plant species RLPs play important roles in development and pathogen defense. Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 (CLV2; AtRLP10) and its maize ortholog FASCINATED EAR2 are required for maintaining the meristematic stem cell population in shoot apical meristems, while Arabidopsis TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM; AtRLP17) controls the initiation of stomatal precursor cells.4–7 The RLP disease resistance gene family comprises the tomato Cf and Ve genes that provide resistance against Cladosporium fulvum and Verticillium spp., respectively,8–10 LeEIX genes that encode receptors for the ethylene inducible xylanase produced by Trichoderma biocontrol fungi,11 apple HcrVf genes that confer resistance to the scab fungus Venturia inaequalis,12 and an Arabidopsis RLP gene (AtRLP52) that provides resistance against the powdery mildew pathogen Erysiphe cichoracearum.13 We recently reported the assembly of a genome-wide collection of T-DNA insertion lines for the 57 Arabidopsis RLP genes (AtRLP) in the Arabidopsis genome.14 This collection was functionally analyzed with respect to plant growth, development and sensitivity to various stress responses including pathogen susceptibility. Only few novel phenotypes were discovered; while AtRLP41 was found to mediate abscisic acid sensitivity, AtRLP30 (and possibly AtRLP18) was found to influence non-host resistance towards Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola.14

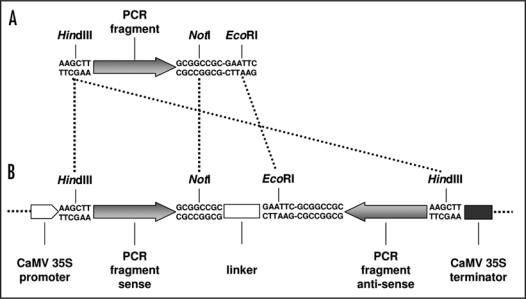

The lack of identification of biological functions for the majority of the AtRLP genes may be caused by functional redundancy. Here, we describe a reverse genetics strategy by employing RNA interference (RNAi) to target the expression of multiple AtRLP genes simultaneously, and thus possibly overcome functional redundancy among AtRLP genes. To select suitable fragments for RNAi silencing, the AtRLP genes were aligned and sequence stretches of a few hundred base pairs (bp) containing minimum one 21 bp stretch with 100% identity to minimum one other AtRLP gene were identified. Specificity of the selected fragments was verified with BLAST searches against the Arabidopsis genome.15 Seven AtRLP gene fragments, varying in length between 238 and 407 bp, were PCR-amplified such that the PCR products contained a 5' BamHI or HindIII site and a 3′ EcoRI and NotI site (Table 1; Fig. 1A) and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands). The resulting plasmids were digested in two separate reactions with HindIII (or BamHI for RNAi constructs 2 and 5) in combination with NotI and in combination with EcoRI. Both inserts were cleaned from gel using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, NL) and subsequently ligated with a NotI- and EcoRI-digested 129 bp spacer segment from the Pichia pastoris Aox-1 gene into the HindIII-digested (or BamHI for RNAi constructs 2 and 5) pGreen plasmid16 to obtain inverted repeat constructs driven by the CaMV 35S promoter that target expression of multiple AtRLP genes (Fig. 1B). The resulting seven plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation, transformed to Arabidopsis,17 and multiple homozygous single-insertion T3 lines were selected on MS plates supplemented with 100 µg/mL kanamycin that were used for functional analysis.

Table 1.

RNAi constructs to target homologous AtRLP genes

| RNAi construct | Tared genea) | Primer name | Restriction site | PCR product | Primer sequence (5′-3′)b) | TF No.c) | Homology tod) | ||

| 1 | AtRLP8 | At154480F | HindIII | 301 bp | AAGCTT-GGTTATCCCAGCAGAGC | 5 | AtRLP14 | (At1g74180) | 21 bp |

| (At1g54480) | At1g54480R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-ATTGGTCGTGGTCCAC | AtRLP21 | (At2g25470) | 28 bp | |||

| 2 | AtRLP53 | At5g27060F | BamHI | 407 bp | GGATCC-AAAGGTGTAGCGATGGAGCTGG | 8 | AtRLP19 | (At2g15080) | 20 + 33 bp |

| (At5g27060) | At5g27060R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-GCTGGCGTGTGAATATCTCTGC | AtRLP34 | (At3g11010) | 22 + 24 + 26 + 28 + 44 + 59 bp | |||

| AtRLP35 | (At3g11080) | 21 + 43 + 55 + 102 bp | |||||||

| AtRLP43 | (At3g28890) | 22 + 24 + 25 + 27 + 29 bp | |||||||

| 3 | AtRLP36 | At13G23010F | HinDIII | 336 bP | AAGCTT-CCGATTCTCCGGACATATCCCT | 7 | AtRLP37 | (At3g23110) | 25 bp |

| (At3g23010) | At3g23010R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-GGCACATGATGGCTTTCTCCAC | AtRLP38 | (At3G23120) | 28 bp | |||

| 4 | AtRLP15 | At1g74190F | HindIII | 289 bp | AAGCTT-CCAGACACATTGCTTGC | 4 | AtRLP13 | (At1g74170) | 22 bp |

| (At1g74190) | At1g74190R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-CATCAGAAGGGAAAGAAATGC | ||||||

| 5 | AtRLP41 | At3g25010F | BamHI | 312 bp | GGATCC-CCGAAATTGCAAGTCCTTCTCC | 9 | AtRLP23 | (At2g32680) | 24 bp |

| (At3g25010) | At3g25010R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-GGCTGAGGAAGTAAGAACC | AtRLP39 | (At3g24900) | 22 + 24 + 54 + 56 bp | |||

| AtRLP40 | (At3g24954) | 25 bp | |||||||

| AtRLP42 | (At3g25020) | 24 + 24 + 26 + 27 + 32 + 36 bp | |||||||

| PGIP | (At3g24982) | 25 bp | |||||||

| 6 | AtRLP47 | At4g13810F | HindIII | 269 bP | AAGCTT-CCTCTCTGGTATTTTTCCAG | 5 | AtRLP48 | (At4g13880) | 22 + 24 + 27 bp |

| (At4g13810) | At4g13810R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-TTCGCAACCTGGAGAAACTTAAAG | AtRLP49 | (At4g13900) | 33 + 36 + 59 + 63 bp | |||

| AtRLP50 | (At4g13920) | 23 + 41 bp | |||||||

| PGIP | (At4g13820) | 21 bp | |||||||

| 7 | AtRLP2 | At1g17240F | HindIII | 238 bp | AAGCTT-TACCAGTCGAAGTTGGCCAG | 8 | AtRLP3 | (At1g17250) | 28 bp |

| (At1g17240) | At1g17240R | EcoRI/NotI | GAATTC-GCGGCCGC-TCAAACTGACCTTCACTGGG | ||||||

Target gene used as template for PCR amplification.

Restriction sites are underlined.

Number of homozygous single-insert lines tested.

Stretches of base pair identities (>20 bp) of the AtRLP fragment in the RNAi construct with the most homologous AtRLP genes indicated.

Figure 1.

Cloning strategy for RNAi constructs. (A) PCR fragments of specific AtRLP fragments are generated with 5′HindIII (or BamHI for RNAi construct 2 and 5) and 3′ NotI and EcoRI restriction sites. (B) Inverted repeat constructs are generated by ligating HindIII (or BamHI for RNAi constructs 2 and 5) and NotI digested PCR fragment and HindIII (or BamHI for RNAi constructs 2 and 5) and EcoRI digested PCR fragment together with a NotI- and EcoRI-digested 129 bp spacer segment from the Pichia pastoris Aox-1 gene into the HindIII-digested (or BamHI for RNAi constructs 2 and 5) pGreen backbone. The fragments are not drawn to scale.

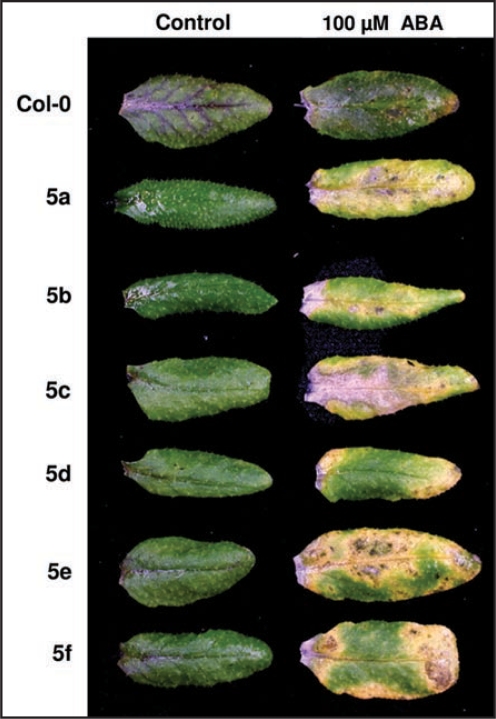

Similar as the individual AtRLP insertion lines,14 also the RNAi lines were analyzed with respect to plant development and sensitivity to various abiotic and biotic stress factors. Development of roots, rosettes, leaf cuticle and flowers as well as stomatal patterning were examined, but no developmental anomalies were observed. In addition, the RNAi lines were assayed for altered sensitivity to plant hormones and abiotic stress factors. The only consistently altered phenotype was observed for lines containing RNAi construct 5 upon exogenous application of the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA), as leaves of the RNAi lines bleached while wild-type leaves remained green (Fig. 2). Since RNAi construct 5 is predicted to target AtRLP41 of which a knock-out has been shown to result in enhanced ABA susceptibility14 this phenotype was expected. Moreover, this observation confirms that RNAi-mediated gene silencing can be used as a mechanism to investigate the function of RLP receptors. To determine whether AtRLP genes play a role in recognition of plant pathogens, similar as the individual AtRLP insertion lines14 the collection of AtRLP RNAi lines was assessed for altered phenotypic responses upon challenge with a range of diverse host-adapted and non-adapted necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens.14,18 In addition to the previously used pathogens,14 we included Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. raphani strain 815, the Verticillium dahliae strains St12.01, St17.01 and JR2, as well as the two oomycete strains Phytophthora brassicae HH/CBS782.97 and CBS686.95 in our analysis. Interestingly, no significant differences were identified when the responses of the RNAi lines were compared to those of the parental Col-0 line upon inoculation with any of the pathogens used.

Figure 2.

RNAi construct 5 triggers ABA-induced chlorosis. Comparison of the leaf phenotype of six independent transgenic lines containing RNAi construct 5 (a to f) with the parental line Col-0 three days after application of 100 mM abscisic acid (ABA).

The Arabidopsis genome harbors 24 loci containing a single AtRLP gene and 13 loci comprising multiple, between two and five, AtRLP genes.14,19 Often, the most homologous AtRLP genes reside at the same locus,14,19 and therefore crossing individual T-DNA insertion lines to obtain knock-out lines for multiple AtRLP genes is nearly impossible. RNAi-mediated gene silencing currently is the most suitable strategy to target expression of several highly homologous genes simultaneously. Based on the sequence comparison between Arabidopsis and rice RLP genes, and building on the hypothesis that developmental genes are less likely to be duplicated and undergo diversifying selection than are disease resistance genes,20 most AtRLP genes were proposed to be candidate disease resistance genes.19 Remarkably, despite an extensive list of pathogens tested, including adapted and non-adapted pathogens of Arabidopsis, we have been able to identify only one AtRLP gene with a role in basal non-host resistance against the non-adapted bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv phaseolicola when screening a genome-wide collection of T-DNA insertion lines in the AtRLP genes.14 It was hypothesized that the lack of identification of biological functions for AtRLP genes may be explained by functional redundancy.14 In the experiments presented in this manuscript we employed RNA interference to interfere with the expression of multiple AtRLP genes at the same time to overcome functional redundancy among AtRLP genes. Nevertheless, no biological functions could be assigned to additional AtRLP genes. Obviously, the targeted AtRLP genes might function in defense against pathogens that have not yet been assayed. As suggested previously,14 if AtRLP genes are active in non-host resistance or basal defense, the array of potential microbial targets may be significantly increased and the response to more microbes or even insects and nematodes should be tested.21 Furthermore, it may be questioned whether the knock-down established by RNAi is sufficiently strong to compromise RLP receptor activity, although gene silencing has been successfully used to compromise the activity of RLP-type disease resistance genes in tomato.22 Also, the observation that transformants expressing RNAi construct 5 phenocopies the AtRLP41 T-DNA insertion allele with respect to ABA responsiveness argues against this possibility. Possibly, however, the RNAi constructs do not silence all redundant AtRLP homologs as efficiently or target all the redundant AtRLP homologs. For instance, RNAi construct 4 that is derived from AtRLP15 is predicted to silence expression of AtRLP13, but not of AtRLP16 which is also close homologue of AtRLP15. Finally, redundant AtRLP genes are not necessarily those with the highest overall homology, since ligand specificity may be determined by only a small sequence stretch, making it difficult to design the most potent RNAi constructs. Therefore, a more extensive analysis using many more RNAi constructs is needed to exclude the possibility that the lack of phenotypes can be explained by a high degree of functional redundancy among the AtRLP genes. Overall, the RNAi lines developed in our studies provide a useful tool for further investigation into roles of the AtRLP genes.

Acknowledgements

B.P.H.J.T. is supported by a Vidi grant of the Research Council for Earth and Life sciences (ALW) of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). This project was cofinanced by the Centre for BioSystems Genomics (CBSG) which is part of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/6543

References

- 1.Jones DA, Jones JDG. The role of leucine-rich repeat proteins in plant defences. Adv Bot Res. 1997;24:89–167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joosten MHAJ, de Wit PJGM. The tomato-Cladosporium fulvum interaction: a versatile experimental system to study plant-pathogen interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruijt M, de Kock MJD, de Wit PJGM. Receptor-like proteins involved in plant disease resistance. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geisler M, Nadeau J, Sack FD. Oriented asymmetric divisions that generate the stomatal spacing pattern in Arabidopsis are disrupted by the too many mouths mutation. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2075–2086. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong S, Trotochaud AE, Clark SE. The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1925–1933. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadeau JA, Sack FD. Control of stomatal distribution on the Arabidopsis leaf surface. Science. 2002;296:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1069596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taguchi-Shiobara F, Yuan Z, Hake S, Jackson D. The fasciated ear2 gene encodes a leucine- rich repeat receptor-like protein that regulates shoot meristem proliferation in maize. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.208501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fradin EF, Thomma BPHJ. Physiology and molecular aspects of Verticillium wilt diseases caused by V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum. Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;7:71–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawchuk LM, Hachey J, Lynch DR, Kulcsar F, van Rooijen G, Waterer DR, Robertson A, Kokko E, Byers R, Howard RJ, Fischer R, Prüfer D. Tomato Ve disease resistance genes encode cell surface-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6511–6515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091114198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomma BPHJ, van Esse HP, Crous PW, de Wit PJGM. Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Passalora fulva), a highly specialized plant pathogen as a model for functional studies on plant pathogenic Mycosphaerellaceae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:379–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ron M, Avni A. The receptor for the fungal elicitor ethylene-inducing xylanase is a member of a resistance-like gene family in tomato. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1604–1615. doi: 10.1105/tpc.022475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malnoy M, Xu M, Borejsza-Wysocka E, Korban SS, Aldwinckle HS. Two receptor-like genes, Vfa1 and Vfa2, confer resistance to the fungal pathogen Venturia inaequalis inciting apple scab disease. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:448–458. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-4-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramonell K, Berrocal-Lobo M, Koh S, Wan JR, Edwards H, Stacey G, Somerville S. Loss-of-function mutations in chitin responsive genes show increased susceptibility to the powdery mildew pathogen Erysiphe cichoracearum. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1027–1036. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang G, Ellendorff U, Kemp B, Mansfield JW, Forsyth A, Mitchell K, Bastas K, Liu CM, Woods-Tör A, Zipfel C, de Wit PJGM, Jones JDG, Tör M, Thomma BPHJ. A genome-wide functional investigation into the roles of receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:503–517. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang JH, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellens RP, Edwards EA, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux PM. pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:819–832. doi: 10.1023/a:1006496308160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomma BPHJ, Penninckx IAMA, Broekaert WF, Cammue BPA. The complexity of disease signaling in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz-Laylin LK, Krishnamurthy N, Tör M, Sjölander KV, Jones JDG. Phylogenomic analysis of the receptor-like proteins of rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:611–623. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leister D. Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recombination in the evolution of plant disease resistance genes. Trends Genet. 2004;20:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stout MJ, Thaler JS, Thomma BPHJ. Plant-mediated interactions between pathogenic microorganisms and herbivorous arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:663–689. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabriels SHEJ, Takken FLW, Vossen JH, de Jong CF, Liu Q, Turk SCHJ, Wachowski LK, Peters J, Witsenboer HMA, de Wit PJGM, Joosten MHAJ. cDNA-AFLP combined with functional analysis reveals novel genes involved in the hypersensitive response. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:567–576. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]