Abstract

Purpose

Early/initiating oncogenic mutations have been identified for many cancers, but such mutations remain unidentified in uveal melanoma (UM). An extensive search for such mutations was undertaken, focusing on the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, which is often the target of initiating mutations in other types of cancer.

Methods

DNA samples from primary UMs were analyzed for mutations in 24 potential oncogenes that affect the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. For GNAQ, a stimulatory αq G-protein subunit which was recently found to be mutated in uveal melanomas, re-sequencing was expanded to include 67 primary UMs and 22 peripheral blood samples. GNAQ status was analyzed for association with clinical, pathologic, chromosomal, immunohistochemical and transcriptional features.

Results

Activating mutations at codon 209 were identified in GNAQ in 33/67 (49%) primary UMs, including 2/9 (22%) iris melanomas and 31/58 (54%) posterior UMs. No mutations were found in the other 23 potential oncogenes. GNAQ mutations were not found in normal blood DNA samples. Consistent with GNAQ mutation being an early or initiating event, this mutation was not associated with any clinical, pathologic or molecular features associated with late tumor progression.

Conclusions

GNAQ mutations occur in about half of UMs, representing the most common known oncogenic mutation in this cancer. The presence of this mutation in tumors at all stages of malignant progression suggests that it is an early event in UM. Mutations in this G-protein provide new insights into UM pathogenesis and could lead to new therapeutic possibilities.

Keywords: uveal melanoma, oncogene, mutation, cancer genetics

INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy and the second most common form of melanoma. Several of the late genetic events in tumor progression and metastasis have been identified in UM, such as the loss of chromosome 3 and the switch from class 1 (low metastatic risk) to class 2 (high metastatic risk) gene expression profile.1-3 In contrast, virtually nothing is known about the early, initiating events in uveal melanocytes leading to malignant transformation and development of a clinically detectable tumor. This deficiency stands in contrast to many other forms of cancer, including cutaneous melanoma, where early oncogenic mutations have been well characterized.

Perhaps the most common signaling pathway affected by early oncogenic mutations is the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, where mutations in BRAF, NRAS, HRAS and KIT lead to constitutive activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, which in turn stimulates the transcription of pro-proliferative genes such as CCND1, JUN and MYC.4, 5 Curiously, mutations in these genes are extremely rare in UM.6-8 Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that mutations affecting the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway are present in UM, since MEK, ERK and ELK are constitutively activated in these tumors.9, 10 Further, the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway target CCND1, which encodes cyclin D1, is overexpressed in most UMs,11, 12 and leads to hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor (Rb) in UM.13, 14 Since amplification of CCND1 is rare in UM,15 CCND1 overexpression is most likely mediated transcriptionally by activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway.

These lines of evidence implicating the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway as a likely location of early or initiating oncogenic mutations in UM prompted us to screen a large number of potential oncogenes in this pathway. This search included 24 genes and was guided by oncogenomic data from comparative genomic hybridization, transcription profiling and in silico gene ontology analysis of public databases. Mutations in GNAQ, a stimulatory αq subunit of heterotrimeric G-proteins that was recently found to be mutated in UM, 16 were found in half of the tumor samples, and the spectrum of GNAQ mutations suggested that this may be an early event in UM pathogenesis.

METHODS

Preparation of RNA and DNA

This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University, and informed consent was obtained from each subject. Tumor samples included 67 primary UMs (9 iris tumors and 58 posterior tumors). Normal DNA samples from peripheral blood were prepared from 22 patients with GNAQ-mutant tumors, as previously described.17 Normal uveal melanocytes were available in two patients with GNAQ-mutant tumors (MM86 and MM101) who had undergone enucleation. To collect melanocytes, the eye was cut in half immediately after enucleation, and normal choroid collected from a location opposite the tumor. This was done before collection of tumor tissue so that none of the instruments had touched the tumor. Melanocytes were then cultured from the choroid sample as previously described, 18 and DNA was obtained from these samples for GNAQ sequencing. Tumor tissue was then obtained, snap frozen and prepared for RNA and DNA analysis as previously described.1, 19 The technique and results of array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) were previously described.19 The techniques for generating transcription profile data using Affymetrix Hu133A and Illumina Human Ref8 BeadChip® arrays were previously described.1, 19, 20

Analysis of array-CGH profiles

Genome-wide CGH data were available on 28 primary UMs from a previously published study.17 CGH profiles were analyzed using CGHminer software (http://wwwstat.stanford.edu/~wp57/CGH-Miner). Microsoft Excel was used to identify small, discrete regions of DNA gain, defined as one or more contiguous probes with a log2ratio ≥ 3 standard deviations of the mean for the entire chromosomal arm in at least 15% of tumor samples.

DNA sequencing

Exon 5 of GNAQ was re-sequenced by routine methods following polymerase chain reaction amplification of exon 5 with primers: GNAQE5L: 5’-TTCCCTAAGTTTGTAAGTAGTGC and GNAQE5R:5’-AGAAGTAAGTTCACTCCATTCC. This generated a product of 317 bp that included codon 209. Additional candidate oncogenes were re-sequenced to search for potential nucleic acid substitutions that could serve as activating mutations. Factors used to choose regions to be re-sequenced included: (1) the locations of reported cancer-related mutations in the Sanger Institute Catalogue of Somatic Mutations (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic), and (2) the locations of catalytic or regulatory domains in the Swiss-Prot Database (http://www.expasy.org/sprot/). For genes without known domains that would be likely targets for mutation, the entire coding region was re-sequenced. Primers were designed with Primer3 software to amplify all coding regions as well as exon-intron boundaries. Sequences were analyzed with Sequencher 4.5 software (GeneCodes, Madison, WI, USA). Non-synonymous nucleotide changes were screened to rule out known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) by querying the alignment of the altered region with the reference DNA sequence in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Primer sequences and other details of our sequencing strategy are available upon request.

Analysis of microarray transcription profiles

Twenty-nine of the tumors in this study (10 GNAQ-wildtype and 19 GNAQ -mutant) were previously analyzed for transcription profile using the Affymetrix U133A GeneChip® array (10 cases) and/or the Illumina BeadChip® array (14 cases) or both (5 cases).1 The clinical, pathologic and molecular information, and microarray platforms used for each tumor sample are indicated in Supplementary Table 1. Affymetrix data were normalized by Robust Multichip Average (RMA) using RMAExpress (rmaexpress.bmbolstad.com), and Illumina data were normalized by the rank invariant method using BeadStudio® software (Illumina). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using Spotfire DecisionSite® software (http://www.spotfire.com) to study unsupervised tumor clustering with respect to GNAQ status. Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) was used to identify genes that were differentially expressed between tumors with and without GNAQ mutation (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM). Median centering and t-test statistic were used as analysis parameters, and the false discovery rate was set to zero. Class 1 and class 2 tumors were analyzed separately. There were only four Affymetrix class 2 tumors, so this subset was excluded from the analysis. The three subsets included: Affymetrix class 1 (six GNAQ-wildtype and five GNAQ-mutant tumors), Illumina class 1 (three GNAQ-wildtype and six GNAQ-mutant tumors) and Illumina class 2 (three GNAQ-wildtype and six GNAQ-mutant tumors). SAM was performed using the Wilcoxon nonparametric method.

Chromosome 3 status and extracellular matrix patterns

Chromosome 3 status was available on 42 of the tumors from a previous study using single nucleotide polymorphisms to detect loss of heterozygosity across the entire chromosome.17 The status of extracellullar matrix patterns was available on 13 patients from a previous study. 21 No additional cases in this cohort were available for this analysis.

Statistical analysis

The patients in this study included a well-characterized cohort of 42 UM patients for whom clinical, pathologic, chromosomal and transcriptional data have been previously published.17, 19, 20, 22 These data included: age, gender, tumor diameter and thickness, ciliary body involvement, histologic cell type, depth of scleral invasion, metastasis, patient outcome, transcription profile class 1 or class 2, status of chromosomes 3, 6p, 8p and 8q, and immunohistochemical staining status for β-catenin, E-cadherin and cytokeratin-18. These parameters were analyzed for association with GNAQ status using MedCalc® version 9.4.2.0 statistical software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher exact test, and continuous variables by Mann-Whitney test. Metastasis-free survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Identification of potential oncogenes

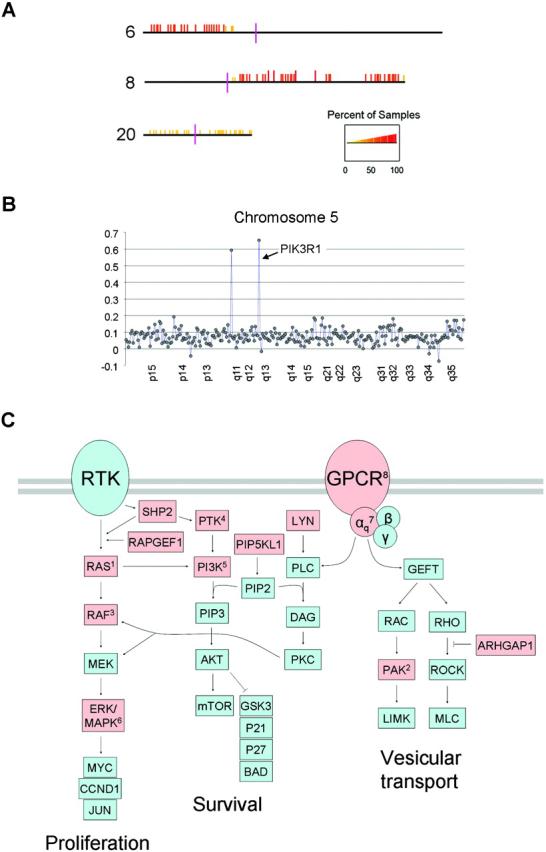

Genome-wide aCGH data were available on 28 primary UMs,19 and these data were re-analyzed to search for regional DNA amplifications that could signify the location of oncogenes. Similar techniques previously have been used successfully to identify, among many other examples, MITF as an oncogene in cutaneous melanoma.23 CGHminer analysis identified frequent gains of large regions of chromosomes 6p and 8q (Figure 1A), which are known regions of chromosomal gain in UM.24-28 CGHminer also detected occasional gains across chromosome 20. However, no small, discrete regions of gain were identified on these or other chromosomal arms. Amplification of an oncogene in a subset of tumors has commonly been used as a means of identifying activating mutations in that oncogene in other, non-amplified, tumor samples. Thus, we searched for discrete regions of DNA gain, defined as one or more contiguous probes with a log2ratio ≥ 3 standard deviations of the mean for the entire chromosomal arm in at least 15% of tumor samples. Using this technique, a small region of DNA gain was identified on chromosome 5q, corresponding to the location of PIK3R1 (Figure 1B), the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, which can activate the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway.29

Figure 1.

Regions of chromosomal gain identified by CGH. (A) CGHminer result for sixteen class 1 and twelve class 2 tumors. DNA gains (indicated by orange and red vertical bars) with respect to chromosomal position (horizontal lines) on chromosomes 6p, 8q and, to a lesser extent, 20p and 20q. The p-arms are depicted to the left, and the q-arms to the right of the centromeres (vertical purple bars). The percent of samples showing DNA gain is indicated by the scale at the bottom. (B) CGH tracing of chromosome 5, showing two peaks with a mean log2ratio ≥ 3 standard deviations above the mean for the chromosomal arm. The larger peak at 5q13.1 corresponded to the location of PIK3R1. The other smaller peak did not correspond to a coding region. (C) Pathways that affect RAF/MEK/ERK activation. Arrows indicate stimulatory interactions, and T-bars indicate inhibitory interactions. Abbreviations: RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor. Other abbreviations are official gene symbols. Notations of specific genes analyzed in this study: 1Ras superfamily of small GTPases: DIRAS2, REM1, GEM, RAB2A, RAB22A, RAB23 (HRAS, KRAS and NRAS were previously analyzed); 2PAK7; 3ARAF, RAF1 and RASIP1 (BRAF was previously analyzed); 4PTK2 and PTK6; 5PIK3R1 regulatory subunit; 6MAPK13 and MAPK14; 7GNAQ; 8GRM1. Red shapes indicate genes that were re-sequenced in this study.

Re-sequencing of potential oncogenes

Along with PIK3R1, we selected 12 genes from chromosomes 6p, 8q, and 20 that are known to play a role in activating the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, exhibited significant expression in uveal melanocytes and UMs in our previously published microarray expression profiles,1, 19, 20 and in most cases, have known mutations in other cancers (Table 1 and Figure 1C). Re-sequencing of these genes in 19 primary UMs revealed no mutations. We extended our re-sequencing to include seven more oncogenes: two RAF family members (ARAF and RAF1), the parallel Ras effector RASIP1, two additional genes that are closely linked to activation of RAF (DIRAS2 and RAPGEF1), the RAS homolog activating protein ARHGAP1, and the PI3K pathway member PIP5KL1. Re-sequencing of these genes in 19 primary UMs also revealed no mutations. Four additional genes were selected because of a known association with a melanoma phenotype (EDG5, GNAQ, GRM1 and PTPN11). Mutations were found in GNAQ, but not in EDG5, GRM1 or PTPN11 (Figure 2). In all cases, mutations in GNAQ occurred at codon 209 (wildtype sequence: CAA).

Table 1.

Summary of Candidate Oncogenes

| Gene Symbol |

Chromosomal Location |

Exons Resequenced |

Primary Tumors Analyzed |

Tumors with Mutations |

RAF/MEK/ERK Pathway |

DNA Gain | Mutated in Other Cancers |

Pigmentation or Melanoma Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARAF | Xp11.4-p11.2 | 9, 12 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| ARHGAP1 | 11p12-q12 | 11 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| DIRAS2 | 9q22.2 | 1 | 19 | 0 | X | |||

| EDG5 | 19p13.2 | 2 | 16 | 0 | X | X | ||

| GEM | 8q13-q21 | 1−3 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| GNAQ | 9q21 | 5 | 67 | 36 | X | X | X | |

| GRM1 | 6q24 | 1−8 | 16 | 0 | X | X | ||

| LYN | 8q13 | 12 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| MAPK13 | 6p21.31 | 1−11 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| MAPK14 | 6p21.3-p21.2 | 1−9 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| PAK7 | 20p12 | 10 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| PIK3R1 | 5q13.1 | 8 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| PIP5KL1 | 9q34.11 | 3 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| PSKH2 | 8q21.2 | 2 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| PTK2 | 8q24-qter | 19 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| PTK6 | 20q13.3 | 1, 7 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| PTPN11 | 12q24 | 3−4, 13 | 16 | 0 | X | X | X | |

| RAB2 | 8q12.1 | 1, 2, 4 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| RAB23 | 6p11 | 2−6 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| RAB22A | 20q13.32 | 1−3 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| RAF1 | 3p25 | 6, 9 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| RAPGEF1 | 9q34.3 | 19 | 19 | 0 | X | X | ||

| RASIP1 | 19q13.33 | 3 | 19 | 0 | X | |||

| REM1 | 20q11.21 | 1−3 | 19 | 0 | X | X | X |

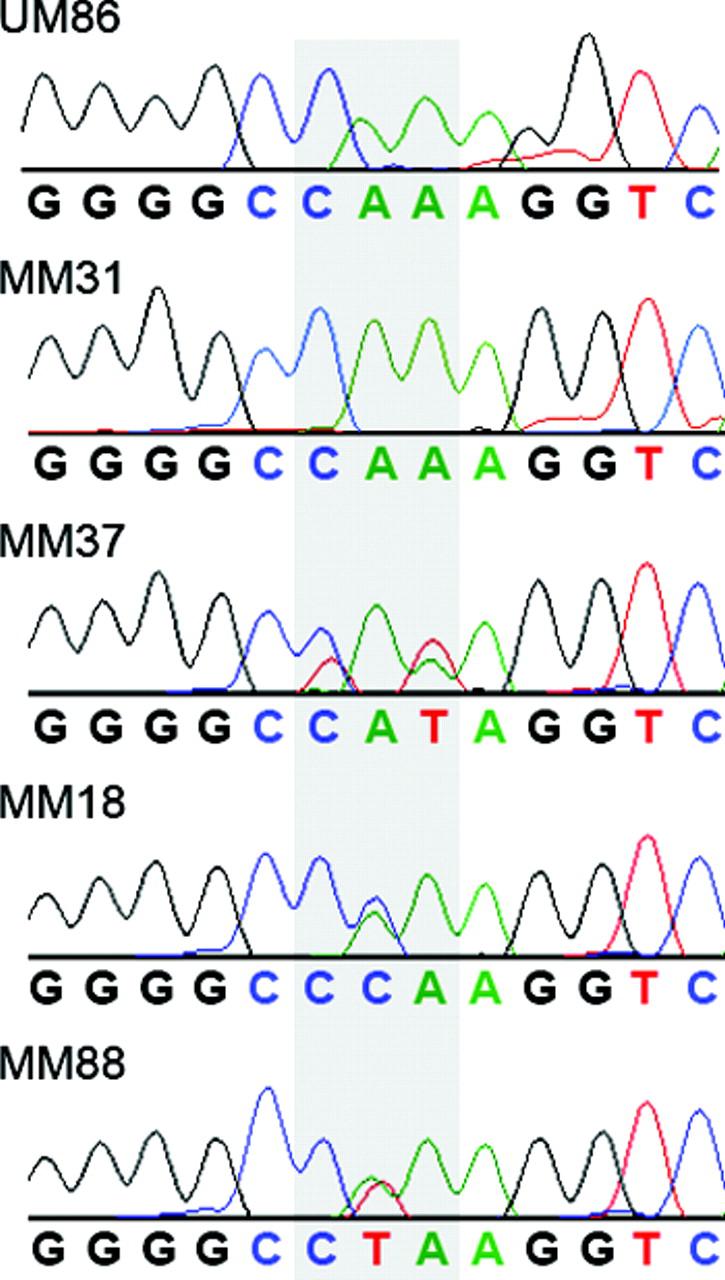

Figure 2.

Representative sequence tracings for GNAQ surrounding codon 209 (shaded). UM86, normal uveal melanocyte sample; MM31, uveal melanoma with wildtype sequence (CAA); MM37, MM18 and MM88, uveal melanomas with the three mutant sequences, as indicated.

GNAQ mutations in uveal melanoma

Prompted by the finding of mutations in GNAQ, analysis of this gene was expanded to include 67 primary UMs. GNAQ mutations were found in 49% (33/67) of tumors, including 22% (2/9) iris UMs and 54% (31/58) of posterior UMs. Mutant sequences included CCA (22 cases), CTA (13 cases) and CAT (one case). Normal DNA samples from peripheral blood were available from 22 patients with GNAQ-mutant primary tumors, and none of these harbored GNAQ mutations. Normal uveal melanocytes surrounding the primary tumor were available in two patients with GNAQ-mutant tumors (MM86 and MM101), and neither melanocyte samples showed GNAQ mutations.

GNAQ mutations and tumor progression

GNAQ mutations exhibited several properties that would be expected for an early or initiating oncogenic event. First, GNAQ mutations did not occur preferentially in tumors with clinical, pathologic or immunohistochemical features indicative of advanced tumor progression (Supplementary Table 2). Second, GNAQ mutations did not correlate with the degree of chromosomal aneuploidy, which is often used as a surrogate measure of temporal tumor progression (P=0.498)(Supplementary Figure 1). Third, there was no correlation between GNAQ mutation and class 2 gene expression profile, which is perhaps the most accurate indicator of advanced tumor progression.1, 19, 20 For this analysis, 30 tumors that were previously profiled for gene expression were analyzed with respect to GNAQ mutation status. Unsupervised analysis using PCA showed no clustering of tumors based on GNAQ status (Supplementary Figure 1). SAM was used to identify genes that were differentially expressed in tumors harboring GNAQ mutations. Consistent with the PCA results, SAM revealed no genes that were consistently differentially expressed between tumors with and without GNAQ mutations (Supplementary Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Activating oncogenic mutations affecting the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway are pervasive in cutaneous melanomas and other forms of cancer, but have rarely been found in UM.7, 8, 30 Mutation of GNAQ at codon 209, which occurs in about half of UMs, represents the first common oncogene mutation in UM and provides important new insights into UM pathogenesis. GNAQ is a heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein alpha subunit that couples G-protein coupled receptor signaling to the RAF/MEK/ERF and other intracellular pathways through protein kinase C activated by stimulation of phospholipase C-beta.31 Codon 209 maps to the catalytic domain of GNAQ, which is involved in GTPase activity. Mutation of this codon inactivates the catalytic domain, preventing hydrolysis of GTP and locking GNAQ in its active, GTP-bound state. This mutation leads to melanocyte proliferation in mice,32 and can cooperate with other oncogenes to transform melanocytes.16 Constitutive activation of GNAQ mimics growth factor signaling in sensitive cells through activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and leads to transcriptional activation of cell cycle genes such as CCND1. This could explain the frequent overexpression of cyclin D1 in UMs.12 The finding of GNAQ mutation as a common and early mutational event in UM could pave the way for novel targeted therapies aimed at inhibiting the GNAQ protein product or other members of the pathway.

In many cancers, mutations in the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway are thought to be early or initiating events in tumorigenesis. For example, BRAF mutations occur very early in cutaneous melanoma, and are even present in benign and pre-malignant nevi.33, 34 Similarly, the absence of correlation between GNAQ mutation and clinical, pathologic, immunohistochemical and genetic indicators of tumor progression, and the presence of the mutation in tumors at all stages of progression, would support the placement of GNAQ mutation as an early event in UM tumorigenesis.

GNAQ mutations were not found in normal DNA from patients bearing GNAQ-mutant tumors. This was an important finding, as it indicated that the GNAQ mutations were acquired somatically and were not present in the germline. A potential effect of GNAQ mutations could be the creation of an expanded pool of morphologically normal but abnormally proliferating melanocytes, as occurred in the mouse model of GNAQ mutation.32 As a result, one might expect to find GNAQ mutations in uveal melanocytes of tumor-bearing eyes. However, in two patients with GNAQ-mutant tumors from whom we were able to obtain uveal melanocytes, no GNAQ mutations were found. GNAQ mutations were more common in UMs located in the posterior uveal tract (ciliary body and choroid) compared to iris UMs, which are located in the anterior uveal tract. Conversely, BRAF mutations are found in some iris UMs,35 but not in posterior UMs. These findings would support the long-held notion that iris UMs and posterior UMs have not only clinical, but also pathogenetic differences.36

The finding of GNAQ mutations in half of UMs raises the exciting possibility that other important oncogene mutations will be found in the other UMs. The role of GNAQ in activating the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway would suggest that future searches for early oncogenic mutations in UM should focus on genes in this pathway. We screened 23 other potential oncogenes in this pathway. Members of the RAS superfamily of small GTPases are commonly mutated in cutaneous melanoma and other cancers, so we re-sequenced several members of this family (DIRAS2, REM1, GEM, RAB2A, RAB22A and RAB23), as well as positive effectors of RAS signaling (DIRAS2, RAPGEF1 and RASIP1), the RAS homolog GTPase activating protein ARHGAP1, and the serine/threonine protein kinase PAK7, which is an effector of RAS homolog RAC/CDC42 GTPases. HRAS, KRAS and NRAS previously have been shown to be free of mutations in UM,6-8 so these were not analyzed here. Similarly, BRAF is frequently mutated in cutaneous melanoma and other cancers, but not in UM,6, 7, 9, 30 so we extended our re-sequencing to the other RAF family members, ARAF and RAF1. The PI3K pathway is activated in UMs 37 and can activate MEK/ERK.29 Thus, we analyzed several members of the PI3K pathway, including PTPN11, PTK2, PTK6, PIK3R1 (the regulatory subunit of PI3K), and PIP5KL1. We also analyzed GRM1 and EDG5, which are G-protein coupled receptors that interact with GNAQ and are associated with melanoma phenotypes.38-40 Even though our mutational screen revealed no additional oncogenic mutations, this screen was valuable in narrowing the search for oncogenic mutations in future studies. To this list can be added the GNAQ-associated genes GNA12−15, GNAS and ENDRB, which were previously analyzed and found to harbor no mutations in UM.16 Future studies should continue to focus on screening for mutations in members of this pathway.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Association between GNAQ status and genetic indicators of tumor progression. (A) Comparison of mean tumor aneuploidy (measured as the % of non-diploid chromosomal arms by array CGH) versus GNAQ mutation status. (B) PCA analysis of 30 tumors with respect to GNAQ status (blue, wildtype; red, mutant). Illumina and Affymetrix datasets were analyzed separately, as indicated. (C) SAM analysis to identify genes differentially expressed based on GNAQ status. In the Affymetrix class 1 dataset, two genes (CPNE6 and SARM1) were expressed at lower levels in mutant tumors (arrows). In the Illumina class 1 dataset, one gene (UGCG) was expressed at higher levels in the mutant tumors (arrow). In the Illumina class 2 dataset, no differentially expressed genes were identified. Overall, no consistently differentially expressed genes (indicated by points located above or below the parallel diagonal lines) were identified.

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and molecular data for tumor samples used in this study.

Supplementary Table 2. GNAQ status and summary of clinical, pathologic, immunohistochemical, chromosomal and transcriptional data on a cohort of 42 well-characterized patients that were used for some of the sub-analyses in this study. These patients have been described in several previous publications.1, 19, 20

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rachel Donaldson and Li Cao for assistance with DNA sequencing.

Supported by grants (to J.W.H.) from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY1316905), Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation, Kling Family Foundation, Tumori Foundation, Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., and Horncrest Foundation, and to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from a Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. and the NIH Vision Core Grant P30 EY 02687.

Footnotes

Disclosure: M.D. Onken, None; L.A. Worley, None; M.D. Long, None; S. Duan, None; M.L. Council, None; A.M. Bowcock, None; J.W. Harbour, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, Harbour JW. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrausch U, Martus P, Tonnies H, et al. Significance of gene expression analysis in uveal melanoma in comparison to standard risk factors for risk assessment of subsequent metastases. Eye. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702779. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tschentscher F, Husing J, Holter T, et al. Tumor classification based on gene expression profiling shows that uveal melanomas with and without monosomy 3 represent two distinct entities. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2578–2584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl C, Guldberg P. The genome and epigenome of malignant melanoma. APMIS. 2007;115:1161–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_855.xml.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimoldi D, Salvi S, Lienard D, et al. Lack of BRAF Mutations in Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5712–5715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz F, 3rd, Rubin BP, Wilson D, et al. Absence of BRAF and NRAS Mutations in Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5761–5766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soparker CN, O'Brien JM, Albert DM. Investigation of the role of the ras protooncogene point mutation in human uveal melanomas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2203–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuidervaart W, van Nieuwpoort F, Stark M, et al. Activation of the MAPK pathway is a common event in uveal melanomas although it rarely occurs through mutation of BRAF or RAS. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2032–2038. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calipel A, Mouriaux F, Glotin AL, Malecaze F, Faussat AM, Mascarelli F. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent proliferation is mediated through the protein kinase A/B-Raf pathway in human uveal melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9238–9250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coupland SE, Anastassiou G, Stang A, et al. The prognostic value of cyclin D1, p53, and MDM2 protein expression in uveal melanoma. J Pathol. 2000;191:120–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200006)191:2<120::AID-PATH591>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brantley MA, Jr., Harbour JW. Deregulation of the Rb and p53 pathways in uveal melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1795–1801. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64817-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brantley MA, Jr., Harbour JW. Inactivation of retinoblastoma protein in uveal melanoma by phosphorylation of sites in the COOH-terminal region. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4320–4323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delston RB, Harbour JW. Rb at the interface between cell cycle and apoptotic decisions. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:713–718. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glatz-Krieger K, Pache M, Tapia C, et al. Anatomic site-specific patterns of gene copy number gains in skin, mucosal, and uveal melanomas detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Virchows Arch. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and intradermal melanocytic proliferations. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature07586. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onken MD, Worley LA, Person E, Char DH, Bowcock AM, Harbour JW. Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 3 detected with single nucleotide polymorphisms is superior to monosomy 3 for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2923–2927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Tran BN, Worley LA, Delston RB, Harbour JW. Functional analysis of the p53 pathway in response to ionizing radiation in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1561–1564. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worley LA, Onken MD, Person E, et al. Transcriptomic versus chromosomal prognostic markers and clinical outcome in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1466–1471. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onken MD, Ehlers JP, Worley LA, Makita J, Yokota Y, Harbour JW. Functional gene expression analysis uncovers phenotypic switch in aggressive uveal melanomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4602–4609. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onken MD, Lin AY, Worley LA, Folberg R, Harbour JW. Association between microarray gene expression signature and extravascular matrix patterns in primary uveal melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:748–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SH, Worley LA, Onken MD, Harbour JW. Prognostic biomarkers in uveal melanoma: evidence for a stem cell-like phenotype associated with metastasis. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:191–200. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghazvini S, Char DH, Kroll S, Waldman FM, Pinkel D. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded uveal melanomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;90:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes S, Damato BE, Giddings I, Hiscott PS, Humphreys J, Houlston RS. Microarray comparative genomic hybridisation analysis of intraocular uveal melanomas identifies distinctive imbalances associated with loss of chromosome 3. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1191–1196. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aalto Y, Eriksson L, Seregard S, Larsson O, Knuutila S. Concomitant loss of chromosome 3 and whole arm losses and gains of chromosome 1, 6, or 8 in metastasizing primary uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilic E, van Gils W, Lodder E, et al. Clinical and cytogenetic analyses in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3703–3707. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehlers JP, Worley L, Onken MD, Harbour JW. Integrative genomic analysis of aneuploidy in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:115–122. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gingery A, Bradley E, Shaw A, Oursler MJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase coordinately activates the MEK/ERK and AKT/NFkappaB pathways to maintain osteoclast survival. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:165–179. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber A, Hengge UR, Urbanik D, et al. Absence of mutations of the BRAF gene and constitutive activation of extracellular-regulated kinase in malignant melanomas of the uvea. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1771–1776. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000101732.89463.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Raamsdonk CD, Fitch KR, Fuchs H, de Angelis MH, Barsh GS. Effects of G-protein mutations on skin color. Nat Genet. 2004;36:961–968. doi: 10.1038/ng1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henriquez F, Janssen C, Kemp EG, Roberts F. The T1799A BRAF mutation is present in iris melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4897–4900. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson E, Margo CE. Iris melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:268–272. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-268-IM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye M, Hu D, Tu L, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hepatocyte growth factor-induced migration of uveal melanoma cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:497–504. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollock PM, Cohen-Solal K, Sood R, et al. Melanoma mouse model implicates metabotropic glutamate signaling in melanocytic neoplasia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:108–112. doi: 10.1038/ng1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kono M, Belyantseva IA, Skoura A, et al. Deafness and Stria Vascularis Defects in S1P2 Receptor-null Mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10690–10696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D-S, Hwang E-S, Lee J-E, Kim S-Y, Kwon S-B, Park K-C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate decreases melanin synthesis via sustained ERK activation and subsequent MITF degradation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1699–1706. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Association between GNAQ status and genetic indicators of tumor progression. (A) Comparison of mean tumor aneuploidy (measured as the % of non-diploid chromosomal arms by array CGH) versus GNAQ mutation status. (B) PCA analysis of 30 tumors with respect to GNAQ status (blue, wildtype; red, mutant). Illumina and Affymetrix datasets were analyzed separately, as indicated. (C) SAM analysis to identify genes differentially expressed based on GNAQ status. In the Affymetrix class 1 dataset, two genes (CPNE6 and SARM1) were expressed at lower levels in mutant tumors (arrows). In the Illumina class 1 dataset, one gene (UGCG) was expressed at higher levels in the mutant tumors (arrow). In the Illumina class 2 dataset, no differentially expressed genes were identified. Overall, no consistently differentially expressed genes (indicated by points located above or below the parallel diagonal lines) were identified.

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and molecular data for tumor samples used in this study.

Supplementary Table 2. GNAQ status and summary of clinical, pathologic, immunohistochemical, chromosomal and transcriptional data on a cohort of 42 well-characterized patients that were used for some of the sub-analyses in this study. These patients have been described in several previous publications.1, 19, 20