To the Editor: Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligate intracellular bacterium in the family Anaplasmataceae. It is considered an emerging pathogen in the United States because it is the causative agent of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (1), a flu-like illness that can progress to severe multisystem disease and has a 2.7% case-fatality rate (2).

In Central and South America, human cases of ehrlichiosis with compatible serologic evidence have been reported in Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, although the bacterium has not been isolated (3). Recently, molecular evidence of E. chaffeensis infection was reported for a symptomatic 9-year-old child in Venezuela (4). In Argentina, antibodies reactive to E. chaffeensis, or an antigenically related Ehrlichia species, were detected in human serum samples during a serologic survey in Jujuy Province, where fatal cases of febrile illness were reported (5).

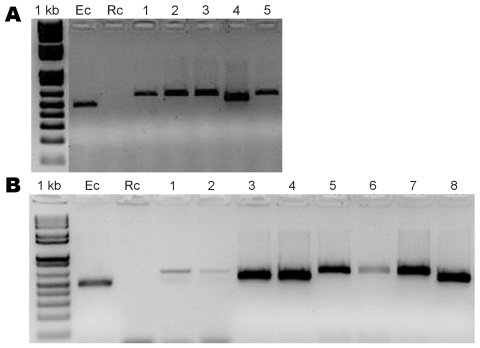

During November–December 2006, we collected ticks by dragging the vegetation and by examining mammal hosts, including humans, in semiarid southern Chaco, Argentina, Moreno Department, Province of Santiago del Estero. Ticks, kept in 70% alcohol, were identified as Amblyomma parvum (n = 200), A. tigrinum (n = 26), and A. pseudoconcolor (n = 13). A sample of 70 A. parvum and 1 A. tigrinum ticks collected on domestic ruminants and canids were subjected to PCR and reverse line blot hybridization by using the TBD-RLB membrane (Isogen Life Science, Maarssen, the Netherlands) (6) to look for Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. DNA was extracted from individual ticks by using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN Valencia, CA, USA); several negative controls (distilled water) for both DNA extraction and PCRs were run alongside the samples in random order throughout the experiments. Primers Ehr-R (5′-CGGGATCCCCAGTTTGCCGGGACTTYTTCt-3′) (6) and Ehr-Fint (5′-GGCTCAGAACGAACGCTG-3′; Inst. Biotecnologia, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, unpub. data) were used to amplify a 500-bp fragment of the 16S gene of Anaplasma/Ehrlichia spp. PCR products were analyzed by reverse line blot hybridization, and 11.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.9–21.0) showed a positive signal to the specific E. chaffeensis probe: 8 A. parvum ticks collected from a dog (n = 1), a fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus, n = 1), goats (n = 2), and cattle (n = 4). No signals to other probes present in the membrane were recorded (A. phagocytophylum, A. marginale, A. centrale, A. ovis, E. ruminatium, E. sp. Omatjenne, E. canis). Further sequence analysis of 16S fragments confirmed the result, with our sequences showing 99.6% identity with the corresponding fragment of the E. chaffeensis strain Arkansas 16S gene (GenBank accession no. EU826516). To better characterize the positives samples, we then amplified variable-length PCR target (VLPT) of E. chaffeensis (7). PCR products of variable length were detected by conventional gel electrophoresis analysis (Figure). Distilled water and R. conorii DNA were used as negative controls, and E. chaffeensis DNA as the positive control. The finding was confirmed by sequence analysis (GenBank accession nos. EU826517 and EU826518)

Figure.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified with Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Ec) variable-length PCR target primers. Rc, Rickettsia conorii (negative control). The sources of DNA templates used for amplification are Amblyomma parvum ticks collected from different hosts: A) 1–5 humans; B) 1 dog, 2 foxes, 3–6 cattle, 7–8 goats. Variable amplicon size represents different genotypes that result from differences in the number of tandem repeats in the 5′ end of the variable-length PCR target; PCR products’ sizes range from 500 bp to 600 bp.

In view of these positive results, another set of 108 specimens was tested by E. chaffeensis VLPT PCR: all the ticks collected on humans (80 A. parvum, 1 A. pseudoconcolor, and 4 A. tigrinum), 18 host-seeking A. parvum ticks, and 5 A. parvum ticks collected on armadillos of the genera Tolypeutes and Chaetophractus. E. chaffeensis was detected in A. parvum ticks only: 5 from humans (6.2%; 95% CI 2.1–14.0; Figure, panel A) and 3 fromhost-seeking ticks (16.7%; 95% CI 3.6–41.4). In total, E. chaffeensis was detected in 9.2% (95% CI 5.4–14.6) of tested A. parvum ticks in the study area. Of the 16 positive A. parvum, 5 were infesting humans.

Little is known about E. chaffeensis epidemiology in South America. In Brazil, wild marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) are suspected to be its natural reservoir, but the tick involved in the transmission cycle is not known (8). In North America, E. chaffeensis sp. is maintained principally by the lone-star tick, A. americanum, and the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (2). However, the possibility of transmission by different ticks and infection among other hosts has been reported; specific antibodies to E. chaffeensis were detected in domestic and wild canids and goats (2), and recently experimental infection was demonstrated in cattle (9). We did find E. chaffeensis organisms in ticks collected on both wild and domestic animals, but the possible role of different mammals as reservoir hosts deserves further investigation. Moreover, the finding of polymorphic VLPT gene fragments in our sample indicates the circulation of E. chaffeensis genetic variants in the study area. VLPT repetitive sequences vary among isolates (7); however, it is not known whether genetic variants differ in pathogenicity or are correlated with geographic distribution or host range.

All positive ticks were A. parvum, a common tick of domestic animals that frequently feeds on humans in Argentina and Brazil and is considered a potential vector of zoonoses (10). In our study area, this tick species was by far the most abundant on humans (93.2%), and our results suggest its potential role as a vector of E. chaffeensis.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Nicholson for providing us with positive controls, J. Stephen Dumler for useful suggestions in molecular diagnostic tools, Paula Ruybal for technical assistance in RLB assay, Alberto Guglielmone for assistance in tick identification, and the families of ‘Uchi’ Escalada (Amama) and of ‘Negro’ Pereira (Trinidad) for helping us with tick collection.

This project received support from the National Institutes of Health Research Grant #R01 TW05836 funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to U.D.K. and R.E.G. Additional funding came from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica de Argentina and University of Buenos Aires (to R.E.G.) and Epigenevac Project (FP6-2002-INCO-DEV-1, EU) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica de Argentina (to M.F.). R.E.G. and M.F. are members of Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas’ Researcher’s Career, P.N. has a CONICET fellowship.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Tomassone L, Nuñez P, Gürtler RE, Ceballos LA, Orozco M, Kitron U, et al. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Amblyomma parvum ticks, Argentina [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2008 Dec [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/14/12/1953.htm

References

- 1.Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, Bakken JS. Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl):S45–51. 10.1086/518146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker DH, Ismail N, Olano JP, McBride JW, Yu XJ, Feng HM. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prevalent, life-threatening, emerging pathogen. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2004;115:375–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.da Costa PS, Valle LM, Brigatte ME, Greco DB. More about human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis in Brazil: serological evidence of nine new cases. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martínez MC, Gutiérrez CN, Monger F, Ruiz J, Watts A, Mijares VM, et al. Ehrlichia chaffeensis in child, Venezuela. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:519–20. 10.3201/eid1403.061304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ripoll CM, Remondegui CE, Ordonez G, Arazamendi R, Fusaro H, Hyman MJ, et al. Evidence of rickettsial spotted fever and ehrlichial infections in a subtropical territory of Jujuy, Argentina. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker CP, de Vos S, Taoufik A, Sparagano OA, Jongejan F. Simultaneous detection of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species in ruminants and detection of Ehrlichia ruminantium in Amblyomma variegatum ticks by reverse line blot hybridization. Vet Microbiol. 2002;89:223–38. 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00179-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumner JW, Childs JE, Paddock CD. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Ehrlichia chaffeensis variable-length PCR target: an antigen-expressing gene that exhibits interstrain variation. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado RZ, Duarte JMB, Dagnone AN, Szabo MBJ. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus). Vet Parasitol. 2006;139:262–6. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.delos Santos JRC, Boughan K, Bremer WJ, Rizzo B, Schaefer JJ, Rikihisa Y, et al. Experimental infection of dairy calves with Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1660–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Guglielmone AA, Beati L, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB, Nava S, Venzal JM, et al. Ticks (Ixodidae) on humans in South America. Exp Appl Acarol. 2006;40:83–100. 10.1007/s10493-006-9027-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]