Abstract

To assess risk for cattle-to-human transmission of prions that cause uncommon forms of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), we inoculated mice expressing human PrP Met129 with field isolates. Unlike classical BSE agent, L-type prions appeared to propagate in these mice with no obvious transmission barrier. H-type prions failed to infect the mice.

Keywords: prions, BSE, PrP, strains, transgenic mice, dispatch

The epizootic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is under control in European countries >20 years after the first cases were diagnosed in the United Kingdom. Thus far, BSE is the only animal prion disease known to have been transmitted to humans, leading to a variant form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) (1). The large-scale testing of livestock nervous tissues for the presence of protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres) has enabled assessment of BSE prevalence and exclusion of BSE-infected animals from human food (2). This active surveillance has led to the recognition of 2 variant PrPres molecular signatures, termed H-type and L-type BSE. They differ from that of classical BSE by having protease-resistant fragments of a higher (H) or a slightly lower (L) molecular mass, respectively, and different patterns of glycosylation (3–5). Both types have been detected worldwide as rare cases in older animals, at a low prevalence consistent with the possibility of sporadic forms of prion diseases in cattle (6). Their experimental transmission to mice transgenic for bovine PrP demonstrated the infectious nature of such cases and the existence of distinct prion strains in cattle (5,7–9).

Like the classical BSE agent, H- and L-type prions can propagate in heterologous species (7–11). Thus, both agents are transmissible to transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP (VRQ allele). Although H-type molecular properties are conserved on these mice (9), L-type prions acquire molecular and neuropathologic phenotypic traits undistinguishable from BSE or BSE-related agents that have followed the same transmission history (7). Similar findings have been reported in wild-type mice (8). An understanding of the transmission properties of these newly recognized prions when confronted with the human PrP sequence is needed. In a previous study, we measured kinetics of PrPres deposition in the brain to show that L-type prions replicate faster than BSE prions in experimentally inoculated mice that express human PrP (7). In a similar mouse model, the L-type agent (alternatively named BASE) was also shown to produce overt disease with an attack rate of ≈30% (12). However, no strict comparison with BSE agent has been attempted. As regards the H-type agent, its potential virulence for mice that express human PrP Met129 remains to be assessed. We now report comparative transmission data for these atypical and classical BSE prions.

The Study

The bovine isolates used in this study have been previously described; they all exhibited high infectivity levels in bovine PrP mice (4,7,9). The equivalent of 2 mg of infected bovine brain tissue was injected intracerebrally into tg650 mice. This line of mice overexpresses (≈6-fold) human PrP with methionine at codon 129 (Met129) on a Zurich mouse PrP null background and has been shown to be fully susceptible to vCJD agent (13). The resulting transmission data available to date are summarized in the Table. The primary transmission of classical BSE isolates was inefficient as judged by the absence of clear neurologic signs and by Western blot detection of PrPres in the brain of only 4/25 inoculated mice. The PrPres banding pattern was essentially similar to that of vCJD (low molecular mass fragments and predominance of diglycoform species; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres) in the brains of human PrP transgenic mice infected with atypical or zoonotic bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) agents. A) Representative Western blot analysis of PrPres extracted (for detailed protocol, see 7) from brain homogenates of mice at terminal stage of disease or at end of lifespan after serial transmission of atypical (L-type and H-type) or classical BSE isolates. The amount of equivalent brain tissue loaded onto the gels was 0.01 mg (BSE; Fr3 isolate, 2nd and 3rd passage), 0.3 mg (L-type and 1st passage of BSE), and 10 mg (PrPres-negative samples). Anti-PrP monoclonal antibody Sha31 was used for PrPres detection. Immunoreactivity was determined by chemiluminescence. B) Ratio of diglycosylated and monoglycosylated PrPres species in the brains of mice after serial transmission of L-type or BSE isolates (data plotted as means ± standard error of the mean). Primary passage of L-type isolates are represented as triangles (orange, It; blue, Fr7; green, Fr10; pink, Fr11) and BSE as squares (light blue, Fr3; red, Ge). Passages are indicated by unfilled symbols of the same color (solid line, second passage; broken line, third passage). The ratio was determined after acquisition of PrPres chemiluminescent signals with a digital imager as previously described (7). Note the distinct glycoform ratio between L-type and BSE groups. It, Italy; Fr, France; Ge, Germany.

Secondary passages were performed by using PrPres-negative or PrPres-positive individual mouse brains. Every time brain homogenate from an aged mouse (>630 days of age) was inoculated, transmission was observed in >80% of the mice, as determined by clinical signs and PrPres accumulation. The mean survival time was ≈600 days (Table; additional data not shown). By the third passage, mean survival time approached ≈500 days, as is usually observed with vCJD cases (Table; 13). The vCJD-like PrPres profile was conserved in all 50 positive brains analyzed (Figure 1). Transmission of L-type isolates to tg650 mice produced markedly different results. First, the 4 L-type isolates induced neurologic disease in almost all mice; survival times averaged 600–700 days (Table). Second, PrPres accumulated in the brain of all 33 mice analyzed. The molecular profile was distinct from BSE or vCJD; prominent monoglycosylated PrPres species resembled those found in cattle (Figure 1). Third, we found neither shortening of the survival time on subpassage (1 isolate tested, 2 brains) (Table; data not shown) nor change in PrPres profile (Figure 1).

Table. Transmission of classical and atypical BSE isolates to transgenic mice expressing human prion protein (Met129)*.

| Isolate | Origin (identification no.) | 1st passage |

2nd passage |

3rd passage |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. affected† | Mean survival time‡ | Total no. affected† | Mean survival time‡ | Total no. affected† | Mean survival time‡ | ||||

| BSE | France (3) | 1/6§ | 872 | 6/7 | 568 ± 65 | 8/8 | 523 ± 22 | ||

| France (3) | 2/6 | 627, 842 | |||||||

| Germany¶ | 1/4§ | 802 | 6/6 | 677 ± 54 | 8/8 | 555 ± 24 | |||

| Italy (128204) | 0/5 | 606–775 | |||||||

| Belgium | 0/4 | 696–829 | |||||||

| L-type | Italy (1088) | 9/9 | 607 ± 23 | 11/11 | 653 ± 13 | NA | |||

| France (7) | 7/7 | 574 ± 35 | 0/8# | >450 | |||||

| France (10) | 8/8 | 703 ± 19 | |||||||

| France (11) | 9/9 | 647 ± 26 | |||||||

| H-type | France (1) | 0/6 | 376–721 | 0/7 | 350–850 | NA | |||

| France (2) | 0/6 | 313–626 | 0/8 | 302–755 | NA | ||||

| France (5) | 0/10 | 355–838 | NA | ||||||

*BSE, bovine spongiform encephalopathy; NA, not available (experiments still ongoing). †Mice with neurologic signs and positive for protease-resistant prion protein by Western blotting. ‡Days ± SE of the mean. For mice with negative results, only the range of survival time is given. §First passage performed on hemizygous mice. Note that the primary transmission of France (3) isolate was performed on both hemizygous and homozygous mice. ¶One passage on transgenic mice expressing bovine prion protein (7). #Ongoing experiment.

In sharp contrast, BSE H-type isolates failed to transmit disease to or even infect tg650 mice. None of the inoculated mice had a detectable level of PrPres in the brain (22 analyzed). Secondary passages were performed with brains of mice that died at various time points. All inoculated mice survived, and none showed a PrPres signal in the brain (15 mice analyzed).

To further compare the behavior of the 3 bovine prions in tg650 mice, we examined the regional distribution and intensity of PrPres deposition in the brain (14). Histoblot analyses (3 brains per infection) were performed on primary (L-type, H-type) and secondary passages (L-type, H-type, BSE). As shown in Figure 2, L-type and BSE agents showed clear differences according to both the aspect and localization of the PrP deposits. Granular PrP deposits were scattered throughout the brain with BSE, as has been previously observed with vCJD (13). The ventral nuclei of the thalamus, cerebral cortex, oriens layer of the hippocampus, and raphe and tegmentum nuclei of the brain stem were strongly stained. With BSE-L, the staining was finer and essentially confined to the habenular, geniculate, and dorsal nuclei of the thalamus; the lateral hypothalamus; the lacunosom moleculare layer of the hippocampus; the superficial gray layer of the superior colliculus; and the raphe nuclei of the brain stem. Finally, PrPres could not be detected on brain sections from mice inoculated with H-type isolates (data not shown), thus confirming the Western blot data.

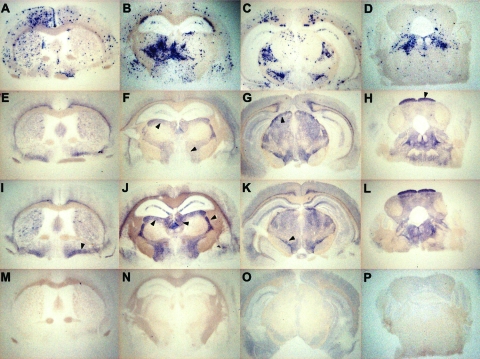

Figure 2.

Representative histoblots in 4 different anteroposterior sections showing the distribution of disease-specific PrPres deposits in the brains of tg650 mice infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or L-type BSE. Panels A–D show infection with BSE (second passage of France 3). Panels E–H show infection with L-type BSE (first passage of France 7). Panels I–L show infection with L-type BSE (second passage of Italy). Panels M–P show brain sections of an age-matched, mock-infected mouse, euthanized while healthy at 700 days postinfection, for comparison. Note the differing aspect and distribution of PrPres deposits between brain of mice infected with BSE and BSE-L (arrowheads). Assignment of the positive brain regions has been made according to a mouse brain atlas after digital acquisition.

Conclusions

We found that atypical L-type bovine prions can propagate in human PrP transgenic mice with no significant transmission barrier. Lack of a barrier is supported by the 100% attack rate, the absence of reduction of incubation time on secondary passage, and the conservation of PrPres electrophoretic profile. In comparison, transmission of classical BSE agent to the same mice showed a substantial barrier. Indeed, 3 passages were necessary to reach a degree of virulence comparable to that of vCJD agent in these mice (13), which likely reflects progressive adaptation of the agent to its new host. At variance with the successful transmission of classical BSE and L-type agents, H-type agent failed to infect tg650 mice. These mice overexpress human PrP and were inoculated intracranially with a low dilution inoculum (10% homogenate). Therefore, this result supports the view that the transmission barrier of BSE-H from cattle to humans might be quite robust. It also illustrates the primacy of the strain over PrP sequence matching for cross-species transmission of prions (15).

Extrapolation of our data raises the theoretical possibility that the zoonotic risk associated with BSE-L prions might be higher than that associated with classical BSE, at least for humans carrying the Met129 PrP allele. This information underlines the need for more intensive investigations, in particular regarding the tissue tropism of this agent. Its ability to colonize lymphoid tissues is a potential, key factor for a successful transmission by peripheral route. This issue is currently being explored in the tg650 mice. Although recent data in humanized mice suggested that BSE-L agent is likely to be lymphotropic (12), preliminary observations in our model suggested that its ability to colonize such tissues is comparatively much lower than that of classical BSE agent.

Acknowledgments

We thank A.G. Biacabe and T. Baron for providing the BSE-L and BSE-H isolates from France and the staff from Unité Expérimentale Animalerie Rongeurs of the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Jouy-en-Josas, for excellent mouse care.

This work was supported by a joint grant from Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique–Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments and by the European Network of Excellence NeuroPrion.

Biography

Dr Béringue is a senior scientist at the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique in Jouy-en-Josas. His primary research interests include the diversity, pathogenesis, and potential of interspecies transmission of animal and human prions.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Béringue V, Herzog L, Reine F, Le Dur A, Casalone C, Vilotte J-L, et al. Transmission of atypical bovine prions to mice transgenic for human prion protein. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2008 Dec [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/14/12/1898.htm

References

- 1.Wadsworth JD, Collinge J. Update on human prion disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:598–609. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Grassi J, Creminon C, Frobert Y, Fretier P, Turbica I, Rezaei H, et al. Specific determination of the proteinase K-resistant form of the prion protein using two-site immunometric assays. Application to the post-mortem diagnosis of BSE. Arch Virol Suppl. 2000;16:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biacabe AG, Laplanche JL, Ryder S, Baron T. Distinct molecular phenotypes in bovine prion diseases. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:110–5. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casalone C, Zanusso G, Acutis P, Ferrari S, Capucci L, Tagliavini F, et al. Identification of a second bovine amyloidotic spongiform encephalopathy: molecular similarities with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3065–70. 10.1073/pnas.0305777101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buschmann A, Gretzschel A, Biacabe AG, Schiebel K, Corona C, Hoffmann C, et al. Atypical BSE in Germany—proof of transmissibility and biochemical characterization. Vet Microbiol. 2006;117:103–16. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biacabe AG, Morignat E, Vulin J, Calavas D, Baron TG. Atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathies, France, 2001–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:298–300. 10.3201/eid1402.071141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beringue V, Andreoletti O, Le Dur A, Essalmani R, Vilotte JL, Lacroux C, et al. A bovine prion acquires an epidemic bovine spongiform encephalopathy strain-like phenotype on interspecies transmission. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6965–71. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capobianco R, Casalone C, Suardi S, Mangieri M, Miccolo C, Limido L, et al. Conversion of the BASE prion strain into the BSE strain: the origin of BSE? PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e31. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Béringue V, Bencsik A, Le Dur A, Reine F, Lai TL, Chenais N, et al. Isolation from cattle of a prion strain distinct from that causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e112. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron T, Bencsik A, Biacabe AG, Morignat E, Bessen RA. Phenotypic similarity of transmissible mink encephalopathy in cattle and L-type bovine spongiform encephalopathy in a mouse model. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron TG, Biacabe AG, Bencsik A, Langeveld JP. Transmission of new bovine prion to mice. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1125–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong Q, Zheng M, Casalone C, Qing L, Huang S, Chakraborty B, et al. Evaluation of the human transmission risk of an atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy prion strain. J Virol. 2008;82:3697–701. 10.1128/JVI.02561-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Béringue V, Le Dur A, Tixador P, Reine F, Lepourry L, Perret-Liaudet A, et al. Prominent and persistent extraneural infection in human PrP transgenic mice infected with variant CJD. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecker R, Taraboulos A, Scott M, Pan KM, Yang SL, Torchia M, et al. Replication of distinct scrapie prion isolates is region specific in brains of transgenic mice and hamsters. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1213–28. 10.1101/gad.6.7.1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Béringue V, Vilotte JL, Laude H. Prion agent diversity and species barrier. Vet Res. 2008;39:47. 10.1051/vetres:2008024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]