Abstract

Despite their common ability to activate intracellular signaling through CD80/CD86 molecules, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4)-Ig and CD28-Ig bias the downstream response in opposite directions, the latter promoting immunity, and CTLA-4-Ig tolerance, in dendritic cells (DCs) with opposite but flexible programs of antigen presentation. Nevertheless, in the absence of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), CD28-Ig—and the associated, dominant IL-6 response—become immunosuppressive and mimic the effect of CTLA-4-Ig, including a high functional expression of the tolerogenic enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Here we show that forced SOCS3 expression antagonized CTLA-4-Ig activity in a proteasome-dependent fashion. Unrecognized by previous studies, IDO appeared to possess two tyrosine residues within two distinct putative immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs, VPY115CEL and LLY253EGV. We found that SOCS3—known to interact with phosphotyrosine-containing peptides and be selectively induced by CD28-Ig/IL-6—would bind IDO and target the IDO/SOCS3 complex for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. This event accounted for the ability of CD28-Ig and IL-6 to convert otherwise tolerogenic, IDO-competent DCs into immunogenic cells. Thus onset of immunity in response to antigen within an early inflammatory context requires that IDO be degraded in tolerogenic DCs. In addition to identifying SOCS3 as a candidate signature for mouse DC subsets programmed to direct immunity, this study demonstrates that IDO undergoes regulatory proteolysis in response to immunogenic stimuli.

Keywords: CD28-Ig, CD80/86 signaling, IL-6, SOCS proteins, tryptophan catabolism

Murine dendritic cells (DCs) present antigen in an immunogenic or tolerogenic fashion, the distinction depending either on the occurrence of specialized DC subsets or on the maturation or activation state of the DC (1). Although DC subsets may be programmed to direct either tolerance or immunity, appropriate environmental stimulation will result in complete flexibility of a basic program (2). Using splenic CD8− and CD8+ DCs that mediate the respective immunogenic and tolerogenic presentation of self peptides, we have previously shown that the activities of both subsets can be subverted by regulatory (Treg) or effector T cells (3). Otherwise immunogenic CD8− DCs became tolerogenic upon CD80 ligation by soluble or cell-bound cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (4, 5), a maneuver initiating indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)-dependent tryptophan catabolism. In contrast, CD28 ligation of CD80/CD86 on IDO-competent CD8+ DCs made these cells capable of immunogenic presentation (6). While transcriptional control by cytokines (7–9) and T cells (10) will effectively result in long-term modulation of Indo (i.e., the gene encoding mouse IDO), the posttranscriptional and posttranslational events contributing to fine-tuning IDO to fully meet the needs of plasticity and redundancy have been unclear (11, 12).

Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins have emerged as critical modulators of cytokine-mediated processes (13). Not only does the feedback inhibitor SOCS3 attenuate IL-6 signaling (14), but also IL-6-dependent upregulation of SOCS3 by soluble CD28 (CD28-Ig) is responsible for inhibiting the IFN-γ-driven transcriptional expression of IDO (6). Although SOCS3 may be an important regulator of IDO—e.g., in response to nitric oxide (15), an inducer of SOCS3 (16)—the underlying mechanisms could be broader in nature than simply opposing IFN-γ signaling and the IFN-γ-like actions of IL-6 (17). SOCS proteins are, in general, critical modulators of immune responses (11), and they possess an Src homology 2 (SH2) domain, which binds phosphotyrosine-containing peptides and a SOCS box. The latter domain participates in the formation of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex and targets several signaling proteins, disparate in nature, for proteasomal degradation (18–21).

Here, we report a positive and biunivocal association between immunogenicity and SOCS3 function in DC subsets programmed by default condition, or otherwise converted by the immunostimulatory ligand CD28-Ig, to direct immunity rather than tolerance. This occurs through ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of IDO, which follows SOCS3 binding of the enzyme through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) typically occurring in receptors that control innate and adaptive immune responses. Besides shedding light on the posttranscriptional mechanisms underlying functional plasticity in DCs, these findings reveal new potentially important roles of SOCS3 in those cells and of ITIMs in IDO.

Results

Association Between Immunogenicity and SOCS3 Function in DC Subsets Programmed or Conditioned to Direct Immunity.

The spleens of DBA/2 mice contain functionally distinct DC populations. The CD8− majority fraction (>90%) mediates immunogenic presentation of the synthetic tumor/self nonapeptide P815AB, while a CD8+ minority fraction (<10%) initiates durable antigen-specific unresponsiveness upon transfer into recipient hosts. The default tolerogenic potential of CD8+ DCs is such that as few as 3% CD8+ admixed with CD8− DCs are sufficient to inhibit induction of immunity to P815AB by the latter cells when antigen-specific skin test reactivity is measured 2 wk after cell transfer. IDO is necessary for default tolerogenesis by CD8+ DCs, which is reinforced by IFN-γ (7) and CTLA-4-Ig (4), but blocked by IL-6 (8), IL-6-inducing maneuvers (3), and CD28-Ig (6, 12). SOCS3, in turn, is both induced and required by CD28-Ig and IL-6 acting on CD8+ DCs to make cells immunogenic (17).

On the basis of preliminary evidence that freshly harvested or cultured CD8− and CD8+ DCs express different levels of Socs3 transcripts on PCR analysis (Fig. 1A), we examined whether forced SOCS3 expression in CD8+ and CD8− DCs would affect their basic presentation programs. In the model system of skin test reactivity to P815AB, transfection of Socs3 mRNA made CD8+ DCs fully immunogenic (Fig. 1B). Transfection also increased the immunogenic potential of CD8− DCs, to an extent capable of releasing those cells from the inhibitory control of cotransferred CD8+ DCs, which would otherwise prevail (Fig. 1C). These data suggested that the level of SOCS3 expression is a major discriminator of the basic function in DC subsets with opposite programs of antigen presentation.

Fig. 1.

SOCS3 expression regulates the default functional program of CD8+ and CD8− DCs. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of Socs3 mRNA expression. Purified CD8+ and CD8− DCs were cultured for different times in the absence of external stimuli, and Socs3 mRNA levels were quantified by real-time PCR using Gapdh normalization. Data are presented as normalized specific gene transcript expression in the samples relative to normalized transcript expression in the respective control cultures—that is, freshly harvested CD8+ or CD8− DCs (fold change = 1; dotted line). Data are means ± SD from four experiments. (Inset) Socs3 expression was evaluated in freshly harvested DC subsets (indicated) by PCR, using Gapdh expression as a control. Overexpression of Socs3 subverts the basal tolerogenic phenotype of CD8+ DCs (B) and increases the immunogenic potential of CD8− DCs (C). Splenic DCs were fractionated according to CD8 expression, pulsed with the P815AB peptide, and transferred into recipient mice to be assayed at 2 wk for skin test reactivity to the eliciting peptide. CD8+ cells were used either alone (B) or as a minority fraction (3%) in combination with CD8− DCs (C). Both subsets were injected either as such or after transfection with control or Socs3 mRNA. The asterisk (P < 0.01−0.001; experimental vs. control footpads) indicates the occurrence of a positive skin test reaction as a result of unopposed immunogenic presentation of the peptide by the DCs. Data are mean values ± SD of three experiments.

Costimulatory/coinhibitory ligands—including CD80 and CD86—expressed by DCs are pivotal in regulating T cell activation. CD80 and CD86 also transduce intracellular signals back into the DC (“reverse signaling”) where they regulate Indo transcription and IDO-dependent tolerogenesis (10). To ascertain whether a dominant role of SOCS3 would contribute to physiological conditioning by T cell ligands, we either silenced or overexpressed SOCS3 in CD8+ or CD8− DCs, which were treated with CD28-Ig, IL-6, or CTLA-4-Ig before cell transfer into recipient hosts to be assayed for skin test reactivity to P815AB. Selected DC cultures were treated with the IDO inhibitor 1-methyl-tryptophan (1-MT). The acquisition of an immunogenic phenotype by CD8+ DCs treated with CD28-Ig or IL-6 was negated by Socs3 silencing, the effect of silencing being strictly dependent on an intact IDO function (Fig. 2 A and B). In both DC subsets, the reinforced (CD8+) or newly induced (CD8−) tolerogenic potential conferred on cells by CTLA-4-Ig—again, dependent on functional IDO—was lost upon overexpressing SOCS3 (Fig. 2C). These data suggested a general and biunivocal relationship between immunogenicity and SOCS3 expression in DC subsets that, either by default or via T cell conditioning, present peptide antigen in an immunogenic fashion. In contrast, induction of IDO-dependent tolerance required a downregulated SOCS3 function.

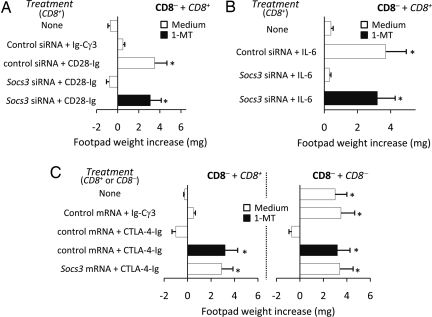

Fig. 2.

SOCS3 expression regulates the acquisition of an immunogenic vs. tolerogenic function in DC subsets in response to environmental stimuli. P815AB-pulsed CD8− DCs (majority population) and CD8+ DCs were transferred into recipient mice to be assayed for skin test reactivity at 2 wk. The IDO inhibitor 1-MT was added to selected cultures at the final concentration of 4 μM. When used in combination with CD8− DCs, the minority CD8+ DC fraction was used as such or after treatment with CD28-Ig (A) or rIL-6 (B), with or without concomitant Socs3 gene silencing by siRNA. Untreated cells and/or cells transfected with control siRNA were also used. In C, minority fractions of peptide-pulsed CD8+ or CD8− DC subsets (indicated) were injected either as such or after transfection with control or Socs3 mRNA and subsequent conditioning by CTLA-4-Ig. In both A and C, Ig-Cγ3 was used as a control for both fusion proteins. *, P < 0.005, experimental vs. control footpads (n = 3).

Inverse Relationship Between IDO and SOCS3-Proteasome-Mediated Effects in DCs Conditioned to Initiate Tolerance.

The proteasome is a major protein-degrading enzyme, which catalyzes degradation of oxidized and aged proteins, signals transduction factors, and cleaves peptides for antigen presentation. The mechanisms of action of SOCS proteins include SOCS box targeting of bound proteins to ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. As mentioned above, 1-MT is a specific and widely used inhibitor of IDO activity (22), and MG132 is a specific proteasome inhibitor. We examined the inverse relationship between SOCS3 and IDO functions by using the two inhibitors in combination. In a skin test assay with P815AB, CD8+ DCs rendered immunogenic by CD28-Ig or IL-6 (Fig. 3A) reverted their phenotype when cotreated with MG132; yet the addition of 1-MT restored immunogenicity. Studies of IDO function in vitro with CD8+ DCs treated with CD28-Ig or IL-6 confirmed that MG132 activated the metabolic conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine—the initial IDO-dependent catabolite—and it did so in a 1-MT-sensitive manner (Fig. 3B). In parallel, CD8+ DCs rendered immunogenic by combined CTLA-4-Ig and Socs3 mRNA treatment were converted to a tolerogenic phenotype by MG132, an effect contingent on functional IDO, as proved by the inclusion of 1-MT (Fig. 4A). In vitro data of tryptophan conversion to kynurenine were consistent with the in vivo data (Fig. 4B). Therefore, an inverse relationship appeared to occur in DCs between functional IDO and SOCS3-proteasome-mediated effects.

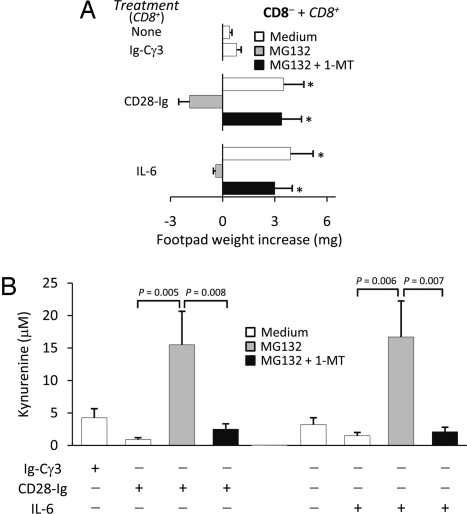

Fig. 3.

The proteasome inhibitor MG132 confers IDO-dependent, immunosuppressive properties on CD28-Ig in CD8+ DCs. CD8+ DCs were conditioned by overnight incubation with CD28-Ig or IL-6. Ig-Cγ3 was used as a stimulation control for CD28-Ig. The proteasome inhibitor, MG132, was added at 10 μM for 1 h before addition of the stimuli. The IDO inhibitor, 1-MT, was added to selective cultures at 4 μM. (A) Conditioned CD8+ DCs were pulsed with the P815AB peptide and injected, in combination with a majority fraction of CD8− DCs, into recipients hosts that were assayed for the development of P815AB-specific skin test reactivity at 2 wk after cell transfer. *, P < 0.005, experimental vs. control footpads. (B) IDO activity was evaluated in terms of kynurenine production in culture supernatants from CD8+ DCs. In both A and B, results are mean values ± SD from three experiments.

Fig. 4.

The proteasome inhibitor MG132 antagonizes SOCS3-dependent immunostimulatory effects in CD8+ DCs used as a minority population in combination with CD8− DCs. CD8+ DCs, used either as such or after transfection with control or Socs3 mRNA, were conditioned by overnight incubation with CTLA-4-Ig. Ig-Cγ3 was used as control. MG132 and 1-MT were added to selective cultures as in Fig. 3. (A) The development of P815AB-specific skin test reactivity was assessed at 2 wk after cell transfer, as in Fig. 3. Data are means (± SD) from three experiments. *, P < 0.001, experimental vs. control footpads. (B) IDO activity was evaluated in terms of kynurenine production in supernatants from cultured CD8+ DCs. Results are mean values (± SD) of three experiments.

Ubiquitin-Proteasome-Mediated Degradation of IDO in DCs.

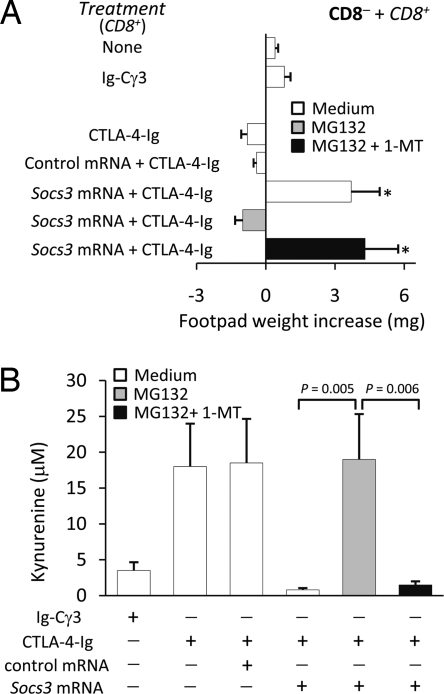

We investigated whether the SOCS3-dependent immunoadjuvant activity of CD28-Ig in DCs is associated with posttranslational modification and proteasomal degradation of IDO. Unfractionated DCs were transfected with IDO-Flag mRNA and treated with CD28-Ig in the presence or absence of MG132. Cells were lysed and IDO-Flag was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag. Sequential immunoblotting was conducted using anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-ubiquitin, and an IDO-specific monoclonal antibody. Aliquots of whole cell lysates from parallel samples were blotted with SOCS3- and β-tubulin-specific antibodies (Fig. 5A). Treatment of IDO-Flag-transfected DCs with CD28-Ig caused the appearance of several tyrosine phosphorylated and ubiquitinated proteins, which, immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag and recognized by anti-IDO antibodies, were greater in size than the IDO-Flag protein. (Any quantitative reduction of 42-kDa IDO-Flag protein would probably be outweighed by the forced IDO-Flag expression.) Interestingly, the bands corresponding to phosphorylated and ubiquitinated proteins became more intense in DCs stimulated with CD28-Ig in the presence of MG132. Moreover, SOCS3 expression was increased by CD28-Ig, and more so by the combined treatment with MG132, suggesting that, in accordance with previous results (20, 23), the SOCS3 protein is degraded concomitantly with its target protein. DCs were next transfected with Socs3 mRNA, and endogenous IDO protein expression was monitored over time in whole cell lysates by means of immunoblotting using anti-IDO; SOCS3 expression was likewise assayed with a specific antibody, demonstrating that SOCS3 overexpression would indeed accelerate IDO protein turnover (Fig. 5B). Therefore, ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of IDO and increased turnover occurred in cells in which CD28-Ig did concomitantly induce a phenotypic change contingent on functional SOCS3.

Fig. 5.

SOCS3 accelerates IDO turnover in DCs by means of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. (A) Unfractionated DCs were transfected with IDO-Flag mRNA and treated with CD28-Ig in the presence or absence of MG132. Cells were lysed and IDO-Flag was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Flag. Sequential immunoblotting was conducted using anti-phosphotyrosine (PY), anti-ubiquitin, and anti-IDO. One-tenth aliquots of whole cell lysates (WCL) from parallel samples were blotted with SOCS3- and β-tubulin-specific antibodies. H, heavy chain of the anti-Flag antibody (55 kDa). One experiment is shown representative of several. (B) Unfractionated DCs were transfected with control or Socs3 mRNA and IDO protein expression was monitored over time (indicated) in WCL by means of Western blot using an IDO-specific monoclonal antibody. SOCS3 expression was also assayed. One experiment is shown representative of three.

Ubiquitin-Proteasome-Mediated Degradation of IDO via SOCS3 Requires Specific Phosphotyrosine Binding.

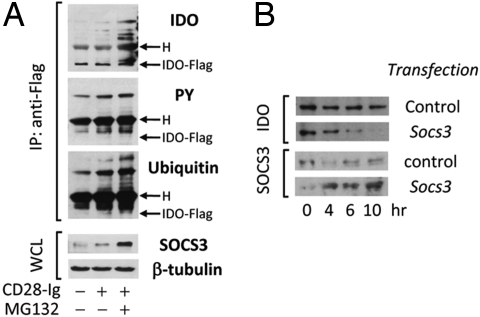

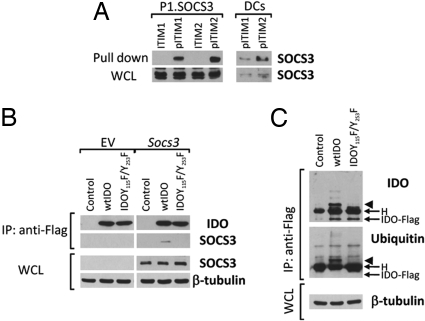

SOCS3-associated SH2 domains bind protein sequences shared by inhibitory receptors (20, 23), i.e., ITIMs. A prototypic ITIM is the I/V/L/SxYxxL/V sequence (24), where x denotes any amino acid. Previously unrecognized by any studies, IDO contains two tyrosines within two distinct canonical ITIMs (ITIM1, VPY115CEL; ITIM2, LLY253EGV). The occurrence of ITIM domains in mouse IDO raised the possibility that the enzyme undergoes ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation after tyrosine phosphorylation and SOCS3 binding via SH2 domains with high affinity for ITIM phosphotyrosine. To verify whether the putative ITIMs in IDO could represent docking sites for SOCS3, biotinylated peptides with phosphorylated or unphosphorylated mouse IDO ITIM1 or ITIM2 sequences were used in a pull-down assay of SOCS3. Lysates from P1 tumor cells stably transfected with Socs3 (P1.SOCS3), and CD28-Ig-treated DCs were reacted with unphosphorylated or phosphorylated IDO peptides and immunoblotted with anti-SOCS3 (Fig. 6A). In both cell lysates, SOCS3 associated with the phosphorylated forms of IDO peptides, although a greater affinity for ITIM2 was observed. (In experiments not reported here mutants selectively lacking ITIM1 or ITIM2 would still bind SOCS3.)

Fig. 6.

IDO contains ITIM sequences that are necessary for SOCS3-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. (A) Lysates from P1 cells stably transfected with Socs3 (P1.SOCS3) and CD28-Ig-treated DCs (DCs) were pulled down with unphosphorylated (ITIM1 and ITIM2) or phosphorylated (pITIM1 and pITIM2) IDO peptides and immunoblotted with anti-SOCS3 antibodies, which were also used in parallel Western blot analyses of WCL. (B) Lysates from P1 cells, transfected with Flag-tagged wild-type IDO (wtIDO) or the mutant IDOY115F/Y253F, were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag and then sequentially blotted with anti-SOCS3 antibodies, which were also used in parallel Western blot analyses of WCL. Empty vector (EV) was used as a control. β-tubulin expression was evaluated as a loading control. H, heavy chain of the anti-Flag antibody. One experiment is representative of three. (C) Unfractionated DCs were transfected with wtIDO-Flag or IDOY115F/Y253F-Flag mRNA and treated with CD28-Ig in the presence of MG132. Cells were lysed and wtIDO-Flag and IDOY115F/Y253F-Flag proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Flag. Sequential immunoblotting was conducted using anti-IDO and anti-ubiquitin. Arrowhead indicates the major ubiquitinated form of IDO. One-tenth aliquots of WCL from parallel samples were blotted with β-tubulin-specific antibodies. One experiment is shown representative of two.

To substantiate a role for IDO ITIM1 and ITIM2 in SOCS3 binding, we generated a construct encoding a Flag-tagged IDO mutant lacking both the ITIM1 and ITIM2 tyrosine residues (IDOY115F/Y253F). We performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with P1 cells transfected stably with Flag-tagged wild-type or mutant IDO and transiently with Socs3, after treatment with pervanadate, a protein-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor (Fig. 6B). Anti-Flag immunoprecipitates were sequentially probed with anti-IDO and anti-SOCS3. Transfected SOCS3 could be detected that coprecipitated with wild-type IDO. In contrast, no SOCS3 association was found with the IDO mutant lacking ITIM1 and ITIM2 tyrosine residues.

We also investigated whether IDO ubiquitination requires ITIMs. Unfractionated DCs were transfected with Flag-tagged wild-type IDO or the double-deficient mutant, and cells were then treated with CD28-Ig in the presence of MG132. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag and then sequentially blotted with anti-ubiquitin and anti-IDO antibodies (Fig. 6C). Only in wild-type IDO-Flag-transfected DCs did several ubiquitinated proteins appear, which were greater in size than the IDO-Flag protein and were recognized by monoclonal anti-IDO antibody. Thus IDOY115F/Y253F would not undergo ubiquitination, emphasizing the obligatory role of ITIM tyrosine residues in the ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of IDO driven by SOCS3.

Discussion

IDO catalyzes the initial and rate-limiting step of tryptophan catabolism in a specific pathway, resulting in a series of extracellular messengers collectively known as kynurenines. IDO has been recognized as an authentic regulator of immunity not only in mammalian pregnancy (22), but also in infection, autoimmunity, inflammation, allergy, transplantation, and neoplasia (10, 11, 25). Its suppressive effects are mediated by DCs and involve tryptophan deprivation and/or production of kynurenines, which act on IDO-negative DCs (26) and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (27). As a result, conditioned DCs mediate multiple effects on T lymphocytes, including inhibition of proliferation (28), apoptosis (29), modulation of pathogenic T-helper responses (30–32), and differentiation toward a regulatory phenotype (33, 34).

Normally expressed at low basal levels, IDO increases in inflammation in response to several stimuli, including a soluble form of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, CTLA-4-Ig. CTLA-4-Ig acts on CD80 molecules to reinforce or initiate tolerogenic signaling in different subsets of DCs, including CD8+ DCs and plasmacytoid DCs (4, 5, 25), or otherwise highly immunogenic CD8− DCs (3). In contrast, CD28-Ig, which acts through CD80/CD86 engagement, is an immune adjuvant (6). Although CD80/CD86 engagement by either ligand will lead to a mixed cytokine response, a dominant IL-6 production in response to CD28-Ig prevents the IFN-γ-driven induction of IDO (6).

SOCS proteins are critical modulators of immune responses (35). Via their SH2 domain, they bind phosphotyrosine-containing sequences in different protein targets resulting in the formation of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that drives proteasomal degradation of SOCS-bound proteins, including specific inhibitory receptors (20, 23), the tyrosine kinase Jak2 (18), and SOCS proteins themselves (36). There is, intriguingly, an inverse correlation between SOCS3 and IDO expression, such that CD28-Ig treatment equates to CTLA-4-Ig treatment in CD8+ DCs lacking SOCS3 (17, 37). Although this effect may in part be consequent to unrestrained IFN-γ signaling and IFN-γ-like actions of IL-6—including enhanced STAT3 phosphorylation and activation of a new set of genes—the role of SOCS3 in regulating tryptophan catabolism could be more complex, and with a broader impact on T cell responses, than previously recognized (8, 17, 19, 34).

We found that not only does SOCS3 influence IL-6 transcriptional programs in DCs, but it can also contribute to posttranscriptional events that directly shape the presentation profile of DC subsets programmed to direct either tolerance or immunity. Both CD28-Ig and IL-6 exerted immunogenic effects on otherwise tolerogenic CD8+ DCs that were contingent on functional SOCS3 in vivo and poor tryptophan catabolism in vitro. In contrast, overexpression of SOCS3 ablated the basic IDO-dependent function of tolerogenic CD8+ DCs and that induced by CTLA-4-Ig in the CD8− subset. Thus both spontaneous and induced immunogenicity is sustained by functional SOCS3 in the DC. In contrast, default or Treg-induced (5) tolerogenic activity might require that SOCS3 not be engaged and IDO protein be, in contrast, functionally expressed. Interestingly, SOCS3 binding and ubiquitination and increased turnover of IDO occurred in cells in which CD28-Ig would upregulate SOCS3 expression and change the basic pattern of antigen presentation. This suggested that not only the immunostimulatory effect of reverse signaling through CD80/CD86 in DCs may exploit SOCS3 as an intermediary, but that a major effect of SOCS3 in DCs involves targeting IDO for ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation.

Ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated protein degradation is central to the regulation of many important biological processes, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA repair, and immune cell signaling; proteasome inhibitors are being developed for treating autoimmune diseases (38). In DCs, the ubiquitin-proteasome system has an established role in antigen processing but also an emerging role in the degradation of transcription factors such as NF-κB or IFN regulatory factors (IRFs) after their initial activation, to avoid possible immunopathology. Among these, IκB kinase family members, originally identified as classical NF-κB activators, are known to be affected (39). It is of interest, therefore, that IDO induction in DCs is driven by the noncanonical—and opposed by the canonical—pathway of NF-κB activation (10, 25, 40). Although the proteasome system could thus contribute to IDO-dependent immunoregulation in multiple ways, perhaps controlling the lifespan of critical NF-κB family members and IRFs, we obtained evidence that IDO is physiologically equipped to undergo rapid turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, as it possesses two putative ITIMs that can act as docking sites for SOCS3. It is worth noting that ITIMs in mouse IDO are apparently conserved in the human counterpart (hITIM1, VPY111CQL; hITIM2, LVY250EGF). Although a phenylalanine at the +3 position relative to ITIM2 tyrosine in human IDO may not be truly canonical (24), a recent combinatorial library approach has revealed that this residue is present in ITIM peptides with high affinity for SH2 domains (41).

Tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs are hallmarks of immunoreceptors that primarily control specific aspects of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Regulation involves signaling through either an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) or an ITIM (42). One such inhibitory motif has recently been found in a G protein-coupled receptor that mediates apoptosis in human malignant cells, thus adding a new dimension to the general role of ITIMs (43). Two sets of observations support a crucial role of these regions in the ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated IDO degradation initiated by SOCS3. Mutation of the central tyrosine in each ITIM completely abolished association with SOCS3 in coimmunoprecipitation experiments. At the same time, mutations also prevented IDO ubiquitination.

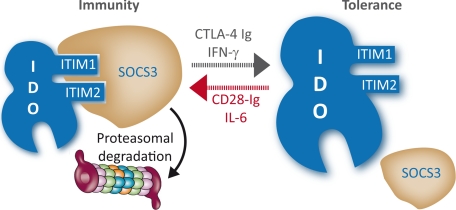

Although DC cell subsets may be programmed to direct either immunity or tolerance, environmental conditioning will result in complete flexibility of a basic program of antigen presentation (1, 2). However, the precise mechanisms responsible for functional plasticity of DCs are poorly defined. We have previously shown that IDO-competent DCs can transfer tolerance from one cell type (CD8+) to another (CD8− DC), in both innate (9) and acquired immunity (26), likely contributing to the onset of “infectious tolerance” (9). Our current study demonstrates that effective onset of immunity within an early inflammatory environment requires that IDO expression be locally extinguished in DCs programmed to direct tolerance (Fig. 7). Autocrine and paracrine IL-6—through SOCS3-mediated effects—is an excellent candidate for exerting pleiotropic effects (8, 17) and downregulating IDO posttranscriptionally. Because DCs are chief regulators of the balance between tolerance and immunity, the finding that SOCS3 influences IDO degradation in those cells may be relevant to the recognition of physiopathologic conditions in which SOCS3 could be poorly expressed (44), and to the implementation of novel immunotherapy protocols targeting the CD28−CD80/CD86 costimulatory axis.

Fig. 7.

Reverse signaling is instrumental in T cell conditioning of antigen-presenting DCs to fully meet the needs of flexibility and redundancy and tip the balance in favor of immunity or tolerance. On engagement of intracellularly signaling CD80/CD86 molecules by CD28 or CTLA-4, SOCS3 could be a major discriminator of function, by affecting IDO lifespan in the DC and thus sustaining or subverting the basic functional program of the DC. Preponderant conditioning by CD28/IL-6 would uniformly ensure immunogenic presentation, whereas the action of CTLA-4/IFN-γ would help establish and spread tolerance.

Methods

Mice, Cell Lines, and Reagents.

Eight- to 10-wk-old female DBA/2J (H-2d) mice were obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories. All in vivo studies were in compliance with National (Italian Parliament DL 116/92) and Perugia University Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. P1.HTR, a highly transfectable clonal variant of mouse mastocytoma P815 (45), referred to as P1, was used. CD28-Ig and CTLA-4-Ig fusion proteins were generated from the extracellular domains of murine CTLA-4 and CD28, respectively, with the Fc portion of IgG3 alone (Ig-Cγ3) representing the control treatment (6).

DC Purification, Treatments, PCR Analyses, and Socs3 Silencing.

All of these procedures have been described in previous publications and are detailed in supporting information (SI) Text.

Construction and Expression of Mouse SOCS3, IDO, and Mutant Enzyme.

Constructs expressing mouse SOCS3 and IDO were generated amplifying the cDNA from purified DCs (Socs3 and Indo genes) with primers containing SpeI (sense, S) and NotI (antisense, AS) restriction enzyme site sequences (SI Text and Table S1). For the IDO construct, the AS primer also contained an N-terminal Flag-encoding sequence and a linker sequence coding for Gly3 to ensure flexibility of the resulting Flag-tagged protein. PCR products were cloned into a pEF-BOS plasmid, as detailed in SI Text.

Immunization, Skin Test Assay, and Kynurenine Assay.

The skin test assay we have been using measures class I-restricted responses to tumor/self peptides (SI Text). Following transfer of P815AB-pulsed DCs, the response to intrafootpad challenge with the peptide was measured, as described previously in detail (6, 46) and also summarized in SI Text. IDO functional activity was measured in vitro in terms of the ability of DCs to metabolize tryptophan to kynurenine, whose concentrations were measured by HPLC as described previously (4, 33).

Peptide Pull-Down Experiments, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblot Analyses.

These procedures, performed according to standard methodologies, are described in full in SI Text.

Statistical Analysis.

Student's t test was used to analyze the results of in vitro studies in which data are mean values (± SD). In the in vivo skin test assay, statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed paired t test by comparing the mean weight of experimental footpads with that of control, saline-injected counterparts (3). Data are mean values (± SD) of three experiments with at least six mice per group per experiment, as computed by power analysis so to yield a power of at least 80% with an α-level of 0.05 (25).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank G. Andrielli for digital art and image editing. This work was supported by funding from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and by the Italian Association for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0810278105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinchieri G, Sher A. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:179–190. doi: 10.1038/nri2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grohmann U, et al. Functional plasticity of dendritic cell subsets as mediated by CD40 versus B7 activation. J Immunol. 2003;171:2581–2587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grohmann U, et al. CTLA-4-Ig regulates tryptophan catabolism in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1097–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallarino F, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1206–1212. doi: 10.1038/ni1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orabona C, et al. CD28 induces immunostimulatory signals in dendritic cells via CD80 and CD86. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1134–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grohmann U, et al. IFN-γ inhibits presentation of a tumor/self peptide by CD8α− dendritic cells via potentiation of the CD8α+ subset. J Immunol. 2000;165:1357–1363. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grohmann U, et al. IL-6 inhibits the tolerogenic function of CD8α+ dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Immunol. 2001;167:708–714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belladonna ML, et al. Cutting edge: autocrine TGF-β sustains default tolerogenesis by IDO-competent dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:5194–5198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puccetti P, Grohmann U. IDO and regulatory T cells: a role for reverse signalling and non-canonical NF-κB activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:817–823. doi: 10.1038/nri2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellor AL, Munn DH. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orabona C, et al. Toward the identification of a tolerogenic signature in IDO-competent dendritic cells. Blood. 2006;107:2846–2854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Shea JJ, Murray PJ. Cytokine signaling modules in inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinrich PC, et al. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hucke C, MacKenzie CR, Adjogble KD, Takikawa O, Daubener W. Nitric oxide-mediated regulation of gamma interferon-induced bacteriostasis: inhibition and degradation of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2723–2730. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2723-2730.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goren I, Linke A, Muller E, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. The suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 is upregulated in impaired skin repair: implications for keratinocyte proliferation. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:477–485. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orabona C, et al. Cutting edge: silencing suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression in dendritic cells turns CD28-Ig from immune adjuvant to suppressant. J Immunol. 2005;174:6582–6586. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ungureanu D, Saharinen P, Junttila I, Hilton DJ, Silvennoinen O. Regulation of Jak2 through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway involves phosphorylation of Jak2 on Y1007 and interaction with SOCS-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3316–3326. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3316-3326.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong PK, et al. SOCS-3 negatively regulates innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in acute IL-1-dependent inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1571–1581. doi: 10.1172/JCI25660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orr SJ, et al. CD33 responses are blocked by SOCS3 through accelerated proteasomal-mediated turnover. Blood. 2007;109:1061–1068. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machado FS, et al. Native and aspirin-triggered lipoxins control innate immunity by inducing proteasomal degradation of TRAF6. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1077–1086. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Munn DH, et al. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science. 1998;281:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orr SJ, et al. SOCS3 targets Siglec 7 for proteasomal degradation and blocks Siglec 7-mediated responses. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3418–3422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravetch JV, Lanier LL. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science. 2000;290:84–89. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grohmann U, et al. Reverse signaling through GITR ligand enables dexamethasone to activate IDO in allergy. Nat Med. 2007;13:579–586. doi: 10.1038/nm1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belladonna ML, et al. Kynurenine pathway enzymes in dendritic cells initiate tolerogenesis in the absence of functional IDO. J Immunol. 2006;177:130–137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallarino F, et al. The combined effects of tryptophan starvation and tryptophan catabolites down-regulate T cell receptor ζ-chain and induce a regulatory phenotype in naive T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6752–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellor AL, Munn DH. Tryptophan catabolism and T-cell tolerance: immunosuppression by starvation? Immunol Today. 1999;20:469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallarino F, et al. T cell apoptosis by tryptophan catabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi T, Hasegawa K, Sasaki Y. Systemic administration of olygodeoxynucleotides with CpG motifs at priming phase reduces local Th2 response and late allergic rhinitis in BALB/c mice. Inflammation. 2008;31:47–56. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi T, et al. 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid inhibits PDK1 activation and suppresses experimental asthma by inducing T cell apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18619–18624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709261104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Luca A, et al. Functional yet balanced reactivity to Candida albicans requires TRIF, MyD88, and IDO-dependent inhibition of Rorc. J Immunol. 2007;179:5999–6008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romani L, et al. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature. 2008;451:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nature06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romani L, Zelante T, De Luca A, Fallarino F, Puccetti P. IL-17 and therapeutic kynurenines in pathogenic inflammation to fungi. J Immunol. 2008;180:5157–5162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tannahill GM, et al. SOCS2 can enhance interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-3 signaling by accelerating SOCS3 degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9115–9126. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.9115-9126.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fallarino F, et al. Ligand and cytokine dependence of the immunosuppressive pathway of tryptophan catabolism in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1429–1438. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett MK, Kirk CJ. Development of proteasome inhibitors in oncology and autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2008;11:616–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaisho T, Tanaka T. Turning NF-κB and IRFs on and off in DC. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tas SW, et al. Noncanonical NF-κB signaling in dendritic cells is required for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) induction and immune regulation. Blood. 2007;110:1540–1549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sweeney MC, et al. Decoding protein-protein interactions through combinatorial chemistry: sequence specificity of SHP-1, SHP-2, and SHIP SH2 domains. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14932–14947. doi: 10.1021/bi051408h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Billadeau DD, Leibson PJ. ITAMs versus ITIMs: striking a balance during cell regulation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:161–168. doi: 10.1172/JCI14843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voisin T, El Firar A, Rouyer-Fessard C, Gratio V, Laburthe M. A hallmark of immunoreceptor, the tyrosine-based inhibitory motif ITIM, is present in the G protein-coupled receptor OX1R for orexins and drives apoptosis: a novel mechanism. Faseb J. 2008;22:1993–2002. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-098723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnston JA, O'Shea JJ. Matching SOCS with function. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:507–509. doi: 10.1038/ni0603-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fallarino F, Uyttenhove C, Boon T, Gajewski TF. Endogenous IL-12 is necessary for rejection of P815 tumor variants in vivo. J Immunol. 1996;156:1095–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grohmann U, et al. CD8+ cell activation to a major mastocytoma rejection antigen, P815AB: requirement for tum− or helper peptides in priming for skin test reactivity to a P815AB-related peptide. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2797–2802. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.