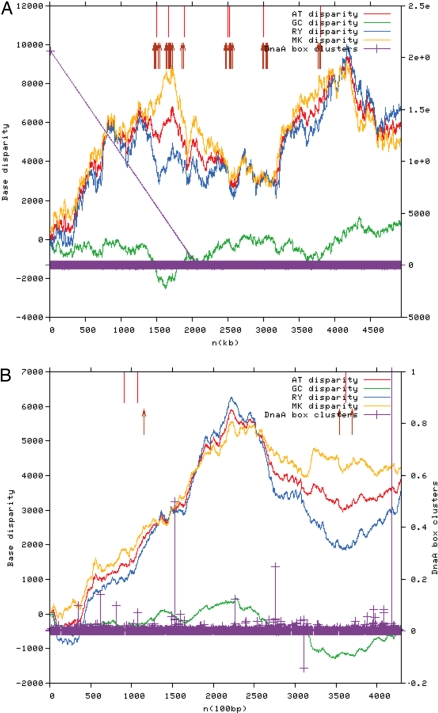

We recently reported (1) our analysis of the Cyanothece 51142 genome, which included an attempt to identify the origins of replication in the circular and linear chromosomes in this genome. We used the web-based Ori-Finder software developed by Gao and Zhang (2). The program output at the time of submission of the revised version of our article is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Output of the Ori-Finder program for the Cyanothece 51142 circular chromosome (A) and linear chromosome (B) using the TTTTCCACA dnaA box motif with 1 allowed mismatch. Predicted candidate sites for the origins of replication are shown by upward-pointing red arrows in both A and B.

Origins of replication have been difficult to determine using similar algorithms in numerous cyanobacterial strains lacking distinct patterns of strand asymmetry (3, 4). According to ref. 3, AT skew exhibited a stronger signal than GC skew in strains closely related to Cyanothece 51142 and thus could be more informative than GC skew. Additionally, multiple peaks suggested the possibility of multiple origins of replication (3). Our analysis revealed 2 large AT skew peaks in the Cyanothece 51142 circular chromosome and 1 in the linear chromosome. Given the weak GC skew signal, strong AT skew signals in disagreement with the GC skew, and multiple candidate dnaA box sites, we felt that the results of our analysis were not sufficient to unequivocally determine the origins of replication.

We thank Gao and Zhang (5) for their further analysis, and we were particularly pleased to see their application of additional oriC selection criteria and their comparison of different cyanobacterial strains. That Gao and Zhang (5) address this issue may provide clarity to this subject in Cyanothece 51142 as well as other cyanobacteria. However, only experimental work will finally answer this question.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Welsh EA, et al. The genome of Cyanothece 51142, a unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterium important in the marine nitrogen cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15094–15099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805418105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao F, Zhang CT. Ori-Finder: a web-based system for finding oriCs in unannotated bacterial genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackiewicz P, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J, Zawilak A, Dudek MR, Cebrat S. Where does bacterial replication start? Rules for predicting the oriC region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3781–3791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura Y, et al. Complete genome structure of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1. DNA Res. 2002;9:123–130. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.4.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao F, Zhang C-T. Origins of replication in Cyanothece 51142. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809987106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]