Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is one of the leading causes of childhood hospitalization and a major health burden worldwide. Unfortunately, because of an inefficient immunological memory, RSV infection provides limited immune protection against reinfection. Furthermore, RSV can induce an inadequate Th2-type immune response that causes severe respiratory tract inflammation and obstruction. It is thought that effective RSV clearance requires the induction of balanced Th1-type immunity, involving the activation of IFN-γ-secreting cytotoxic T cells. A recognized inducer of Th1 immunity is Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), which has been used in newborns for decades in several countries as a tuberculosis vaccine. Here, we show that immunization with recombinant BCG strains expressing RSV antigens promotes protective Th1-type immunity against RSV in mice. Activation of RSV-specific T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-2 was efficiently obtained after immunization with recombinant BCG. This type of T cell immunity was protective against RSV challenge and caused a significant reduction of inflammatory cell infiltration in the airways. Furthermore, mice immunized with recombinant BCG showed no weight loss and reduced lung viral loads. These data strongly support recombinant BCG as an efficient vaccine against RSV because of its capacity to promote protective Th1 immunity.

Keywords: Th1 cell response, RSV, immunopathology, T cell immunity

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is an enveloped, negative, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family with a genome that encodes for 11 proteins (1). This virus is the leading cause of viral bronchiolitis and pneumonia worldwide, infecting more than 70% of children in the first year of life and nearly 100% of children by age 2 years (2). Despite being highly infectious, RSV does not induce an effective immunological memory, and repeated infections are therefore very frequent (3, 4). Although symptoms associated with RSV infection usually manifest as rhinitis in adults, in premature infants, the elderly, and immunosuppressed individuals RSV infection frequently leads to severe symptoms and airway obstruction (5, 6). Furthermore, it has been proposed that exposure to RSV infection early in life can lead to increased susceptibility to recurrent allergic wheezing and asthma during the following years (7). Considering epidemiological data, RSV is responsible for a health problem that is extremely expensive for individuals, governments, and health care systems. Unfortunately, to date there are no commercially available vaccines against this pathogen. Vaccine trials for RSV were first carried out with a formalin-inactivated RSV formulation (FI-RSV) in the mid-1960s (8). However, vaccinated children experienced exacerbated pulmonary disease and required hospitalization upon subsequent RSV infection, whereas nonvaccinated control children experienced significantly milder symptoms (8, 9). The failure of FI-RSV remained unexplained for at least 2 decades, primarily because of the poor understanding of the immune responses triggered by RSV infection. However, recent studies have suggested that the FI-RSV vaccine failed because of the fact that it promoted an allergic-like Th2 immune response against the virus (10–12). This particular Th2-type response is characterized by the activation and proliferation of CD4+ T cells that secrete a pattern of cytokines that promote increased and accelerated infiltration of eosinophils and neutrophils into the lung tissues. Furthermore, this allergic-like cellular environment dampens CD8+ cytotoxic T cell activation and effector functions, such as the secretion of IFN-γ (13). As a result, clearance of RSV is delayed, lung damage is induced, and virus dissemination is promoted.

Over the last few years, several experimental approaches aimed at developing an effective vaccine against RSV have been designed and assessed, such as attenuated RSV particles (14), recombinant viruses (different from RSV) that express RSV antigens (15–17), purified RSV proteins administered with bacterial adjuvants (17, 18), RSV proteins packed as immune stimulating complexes (19), and RSV sequence peptides applied together with adjuvants (20). Although several RSV vaccine candidates may currently be at the end of their corresponding clinical trials around the world, most of these approaches unfortunately promise to be expensive to the point of being unaffordable for middle/low socioeconomic groups. Alternatively, the use of recombinant bacteria for RSV antigens as candidate vaccines against this virus has not been evaluated.

Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is currently used worldwide as a vaccine against tuberculosis and has been used by more than 1 billion humans since its introduction in 1921. In both adults and newborns, BCG induces cell-mediated immune responses and Th1 cytokines that persist for at least 1 year after vaccination (21–23). Because of the fact that BCG vaccination has been shown to be safe in newborns, infants, and adults, this bacterium arises as an attractive vaccine vector candidate for recombinant antigens. Indeed, several studies have shown that recombinant BCG strains efficiently induce Th1 responses against several pathogens and diseases (24–32).

Here, we have evaluated whether BCG strains expressing RSV antigens promote a protective immune response against RSV infection in mice. Our data show that vaccination with recombinant BCG strains expressing RSV proteins N or M2 induces protective immunity against viral infection. The BCG-based vaccine was able to reduce weight loss, lung viral protein loads, and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration in the airways of RSV-challenged mice. This protective response is consistent with increased secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 by T cells stimulated in vitro with RSV proteins. In addition, adoptive transfer of T cells obtained from mice vaccinated with recombinant BCG can protect naive mice from RSV challenge. In summary, our results suggest that recombinant BCG expressing RSV antigens can be used as a safe and protective vaccine against virulent RSV by inducing an efficient Th1-polarized, T cell-mediated specific immunity.

Results

Immunization with Recombinant BCG Reduces the Severity of RSV-Induced Disease.

Genes coding for RSV-N and RSV-M2 proteins were cloned into the integrative plasmid pMV361 (24) to produce the recombinant BCG-N and BCG-M2 strains. These antigens were chosen based on their previously reported capacity to induce RSV-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses (33, 34). Here, we tested whether expression of these antigens in BCG could promote protective T cell immunity against RSV.

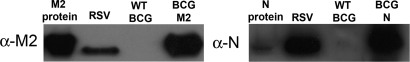

As shown in Fig. 1, N and M2 proteins were efficiently expressed by both recombinant BCG strains. Quantitative Western blot assay revealed that these recombinant BCG strains expressed ≈2.3 ng/106 cfu N protein and 5.7 ng/106 cfu M2 protein (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Expression of RSV M2 and N proteins by recombinant BCG strains. BCG was electrotransformed with plasmid pMV361-M2 or pMV361-N and selected on solid 7H10 medium supplemented with 20 μg/mL kanamycin. Expression of recombinant RSV proteins was assessed by Western blot analysis using rabbit polyclonal antisera specific for the M2 or N protein. A total of 25 μg of whole proteins prepared from BCG-M2 or BCG-N was loaded in each gel. As positive controls, recombinant N or M2 proteins and total proteins of RSV-infected HEp-2 cells were loaded. As negative control, whole proteins prepared from WT-BCG (nonrecombinant) were included.

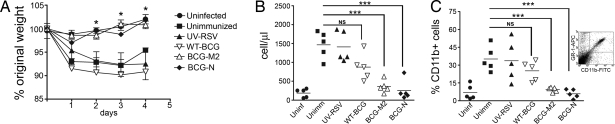

To evaluate whether recombinant BCG strains can protect animals from virulent RSV challenge, 4- to 6-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with 108 cfu of either BCG-N or BCG-M2 using a single subdermal injection in the dorsal flank. Control groups received PBS-Tween 0.02% (unimmunized), 1 × 107 pfu of UV-inactivated RSV (UV-RSV), 108 cfu of either nonrecombinant BCG (WT-BCG) or ovalbumin-recombinant BCG (BCG-OVA). Twenty-one days after immunization, all animals were challenged with 1 × 107 pfu of virulent RSV, and body weight was determined daily for 4 days after infection. As shown in Fig. 2A, significant weight loss was observed for unimmunized animals or mice immunized either with UV-RSV or WT-BCG, as well as BCG-OVA (data not shown). These data are consistent with previous studies indicating that naive mice challenged with RSV can show significant weight loss as early as 24 h after infection (35–37). In sharp contrast, mice immunized with either BCG-N or BCG-M2 showed no significant weight loss after RSV challenge, similarly to uninfected mice (Fig. 2A). These observations were confirmed when disease severity was evaluated using computerized axial tomography (CAT) scan. Signs of pulmonary inflammation could be observed in unimmunized animals 3 days after RSV challenge as pneumonia foci on CAT scan images [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1 and Movie S1]. In contrast, mice immunized with recombinant BCG expressing RSV antigens showed neither pneumonia foci nor lung inflammation after RSV challenge, and their pulmonary parenchyma was similar to that of uninfected mice (Fig. S1 and Movies S1–S3). These data suggest that vaccination with BCG-N or BCG-M2 can significantly reduce RSV-related disease symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Immunization with BCG-N and BCG-M2 protects mice against RSV. Groups of BALB/c mice (5 to 6 weeks of age) received subdermal immunization with 1 × 108 cfu of WT-BCG, BCG-M2, BCG-N, or UV-inactivated RSV and infected with 1 × 107 pfu RSV. Uninfected and unimmunized mice were included as control groups. (A) Body weight loss after RSV infection. Weight loss for BCG-M2-immunized and BCG-N-immunized mice was significantly lower than for mice immunized with WT-BCG or UV-RSV and unimmunized mice (*, P < 0.04, Student's t test between unimmunized and BCG-M2 or BCG-N values). (B) Number of cells in BALs 4 days after RSV infection. BAL cells were obtained as described in Methods and counted with a Neubauer chamber (HBG, Germany). Symbols represent individual mice, and horizontal lines represent means. Cell counts in BALs were significantly lower in mice immunized with BCG-N and BCG-M2 compared with unimmunized mice (***, P < 0.001, Student's t test between unimmunized and BCG-N or BCG-M2 values; NS, nonsignificant, Student's t test between unimmunized and WT-BCG values). (C) Percentage of CD11b-positive cells in BAL 4 days after RSV infection. BAL cells were stained with an FITC-labeled anti-CD11b antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Symbols represent individual mice, and horizontal lines represent means. CD11b-positive cell counts were significantly lower in mice vaccinated with BCG-N and BCG-M2 compared with unimmunized mice (***, P < 0.001, Student's t test between unimmunized and BCG-N or BCG-M2 values; NS, nonsignificant, Student's t test between unimmunized and WT-BCG values). Inset shows a CD11b/GR1 dot plot for BAL cells from RSV-infected mice.

Immunization with Recombinant BCG Prevents Recruitment of Inflammatory Cells into the Airways.

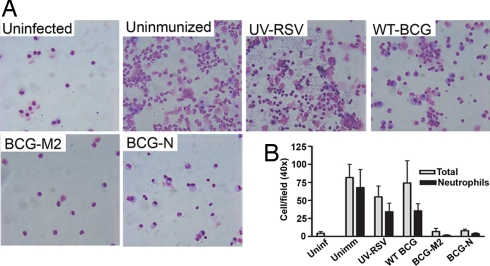

Consistent with the data shown above, RSV challenge caused massive infiltration of inflammatory cells into the airways of unimmunized mice, as well as in mice immunized either with WT-BCG, UV-RSV (Fig. 2B), or BCG-OVA (data not shown). Flow cytometry revealed that most infiltrating cells were positive for the surface marker CD11b (Fig. 2C). Because CD11b-positive cells in bronchoalveolar lavages (BALs) were also positive for Ly-6G/Ly-6C marker (GR1) (Fig. 2C Inset), it is likely that most of the infiltrating cells were neutrophils. Cytospin preparation of BAL fluid after RSV challenge confirmed substantial infiltration of neutrophils in the airways of unimmunized mice and mice immunized with WT-BCG or UV-RSV (Fig. 3), as well as mice immunized with BCG-OVA (data not shown). Contrarily, after RSV challenge no significant recruitment of CD11b+ cells to the airways was observed for mice immunized either with BCG-N or BCG-M2 recombinant strains (Fig. 2C). In addition, immunization with recombinant BCG strains also prevented RSV-induced neutrophil invasion of BALs (Fig. 3). These results suggest that vaccination with BCG-N or BCG-M2 can significantly reduce the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways after RSV infection.

Fig. 3.

Immunization with BCG-M2 or BCG-N prevents airway infiltration by neutrophils after RSV infection. (A) Four days after RSV challenge, BALs obtained from unimmunized or immunized mice with BCG-M2, BCG-N, WT-BCG, or UV-RSV were spun on glass slides, stained with May-Grunwald and Giemsa, and observed under a light microscope at 40× magnification. As a control, BALs from uninfected mice were included. (B) Graph shows the amount of total cells (gray) and neutrophils (black) per field, as quantified by light microscopy at 40× magnification in at least 6 random fields per sample. Bars represent means ± SE.

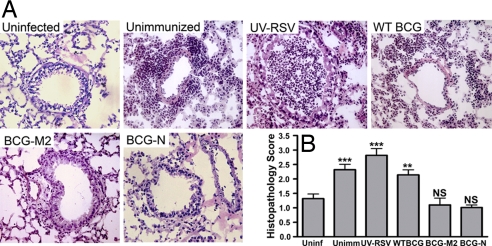

Immunization with Recombinant BCG Prevents Histopathology and Viral Load in Lungs of RSV-Infected Animals.

Five days after RSV challenge, lung tissue from unimmunized or WT-BCG-immunized mice showed an elevated pulmonary histopathology score (HPS, Fig. 4B), as evidenced by significant inflammatory cell infiltration in alveoli and peribronquial tissues (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, mice immunized with UV-RSV and challenged with RSV showed increased lung inflammation, as evidenced by higher infiltration of inflammatory cells in alveoli, bronchioles and peribronchiolar tissues (Fig. 4). Consistent with the massive infiltration of inflammatory cells, increased eosinophil infiltration (Fig. S2) and mieloperoxidase activity (data not shown) was observed in the lung tissue of unimmunized and UV-RSV-immunized mice. These findings suggest that the pronounced weight loss observed in control mice after RSV infection is related to neutrophil infiltration in the airways and lung inflammation. In contrast, mice immunized with BCG-N or BCG-M2 showed reduced HPS (Fig. 4B), as evidenced by significantly less cellular infiltration in the lungs in response to RSV challenge and lung histology equivalent to uninfected mice (Fig. 4A). Consistently, no significant eosinophil infiltration in lung tissue was observed for mice immunized either with BCG-M2 or BCG-N (Fig. S2).

Fig. 4.

Immunization with BCG-M2 and BCG-N reduces inflammatory cell infiltration into the lungs after RSV infection. (A) Four days after RSV infection, mouse lungs were removed and fixed with paraformaldehyde, and 5-μm cuts were stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Significant polymorphonuclear cell infiltration can be observed in unimmunized, UV-RSV, and WT-BCG-immunized mice. Photos are representative of 3 to 6 independent experiments. (B) HPS for each group: 0, no cellular infiltration; 1, minimal cellular infiltration; 2, slight cellular infiltration; 3, moderate cellular infiltration; 4, severe cellular infiltration, as described in Methods (NS indicates nonsignificant; **, P < 0.0036, ***, P < 0.0001, Student's t tests between uninfected and each individual group).

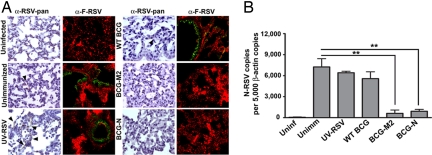

Presence of viral proteins in lung tissues after RSV challenge was determined by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence using an HRP-labeled IgG RSV-specific antiserum and a biotin-labeled anti-RSV-F antibody, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5A, positive staining for RSV proteins could be detected in respiratory epithelia of unimmunized, UV-RSV- and WT-BCG-immunized mice. These data suggest that RSV replication takes place in lungs of control mice after viral challenge. On the contrary, RSV proteins could not be detected in the respiratory epithelia of mice immunized with recombinant strains of BCG-N or BCG-M2 (Fig. 5A). These results are consistent with quantitative real-time PCR data showing that viral RNA loads in lungs were reduced significantly only in BCG-N-immunized and BCG-M2-immunized mice, compared with unimmunized, WT-BCG or UV-RSV-immunized mice (Fig. 5B). These observations support the notion that vaccination with BCG-N or BCG-M2 can induce protective immunity in mice, reducing viral loads in lungs and preventing excessive inflammatory cell recruitment after RSV infection.

Fig. 5.

Immunization with BCG-M2 and BCG-N reduces virus presence in lung tissues after RSV infection. (A) Four days after infection, lungs were removed, fixed with paraformaldehyde, and stained with an HRP-labeled anti-RSV antibody [first and third columns (arrowheads show positive staining)] or with a biotin-labeled anti-F antibody followed by streptavidin-FITC (second and fourth columns), as described in SI Methods. Fluorescence counterstaining derives from a Cy3-conjugated anti-von Willebrand factor antibody. Positive staining is observed in lungs of unimmunized, UV-RSV, and WT-BCG-immunized mice. Data shown are representative of 3 to 6 independent experiments. (B) Total RNA from lungs of control and infected animals were obtained and reverse transcribed to quantify the number of N-RSV copies by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as the number of N-RSV gene copies per 5,000 copies of β-actin gene (**, P < 0.01, 1-way ANOVA).

Mice Immunized with Recombinant BCG Exhibit RSV-Specific T Cells That Secrete Th1 Cytokines

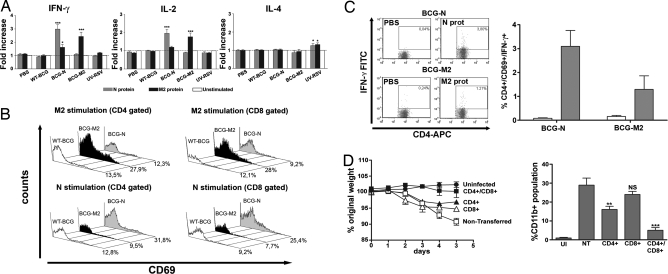

To evaluate whether humoral or cellular adaptive immunity is induced by BCG-N and BCG-M2, IgG titers specific for N or M2 were determined at 7, 14, and 21 days after immunization. No significant increase in anti-N or anti-M2 IgG serum titers could be observed for any of the groups of immunized animals, compared with the unimmunized controls (data not shown). These data suggest that a T cell immune response rather than a humoral response might preferentially be induced by immunization with recombinant BCG. To evaluate this notion, cytokine secretion was determined for T cells obtained from spleens 21 days after immunization in response to antigenic stimulation. Cells were restimulated in vitro for 5 days with recombinant N or M2 proteins, and IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 were measured in culture supernatants. As shown in Fig. 6A, spleen cell suspensions obtained from mice immunized with BCG-N secreted considerable amounts of IFN-γ and IL-2 only in response to N protein. Similarly, cell suspensions obtained from mice vaccinated with BCG-M2 secreted significant amounts of IFN-γ and IL-2 only when stimulated with M2 protein. In contrast, IFN-γ and IL-2 were not detected in the supernatant of cells derived from unimmunized mice or mice immunized with UV-RSV or BCG-WT (Fig. 6A). Although only a modest increase in IL-4 secretion could be detected for T cells obtained from mice immunized with UV-RSV (Fig. 6A), no significant secretion of any Th2-type cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-5, could be measured for T cells obtained from mice immunized with BCG-M2 or BCG-N (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Immunization with BCG-M2 and BCG-N induces the secretion of Th1-type cytokines and promotes activation of antigen-specific T cells in the spleen. BALB/c mice were immunized with either 100 μL of PBS-Tween 0.02%, 1 × 108 cfu of WT-BCG, BCG-M2, BCG-N, or with 1 × 107 pfu of UV-inactivated RSV. After 21 days of vaccination, spleen cells were recovered and stimulated with 10 μg/mL of either M2 or N proteins for 5 days to evaluate cytokine secretion. (A) IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 secretion was detected in supernatants of cell suspensions, by ELISA. Spleen cells derived from BCG-M2 or BCG-M secreted significant amounts of IFN-γ and IL-2 after stimulation with their cognate proteins (***, P < 0.0002; *, P = 0.02, Student's t test). Secretion of IL-4 was only observed in spleen cells of mice immunized with UV-RSV (*, P = 0.02, Student's t test). (B) CD69 expression on the surface of T cells after stimulation with M2 and N protein. Spleen cell suspensions were stimulated with 10 μg/mL N or M2 proteins or left untreated for 72 h, stained with PE anti-CD69, FITC anti-CD8a, and allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD4 antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry, as described in SI Methods. Representative histograms derived from 3 independent experiments show profiles of CD69 expression by CD4+ or CD8+ cells. Numbers in each histogram are the percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ populations positive for CD69. (C) Intracellular IFN-γ production by T cells from BCG-M2-immunized or BCG-N-immunized mice. Representative dot plots of CD4+/IFN-γ+ cells (CD69 gated) and a graph summarizing percentages of CD4+/CD69+/IFN-γ+ T cells (means ± SE). White bars are cell stimulated with PBS and gray bars are cells stimulated with N or M2 recombinant proteins, respectively. (D) Transfer of T cells from BCG-N-immunized mice protects against RSV. T cells obtained from BALB/c mice 21 days after immunization with BCG-N were stimulated for 3 days with N protein and intravenously injected into naive BALB/c mice. RSV-induced weight loss (Left) and BAL infiltration by CD11b+ cells (Right) in BALB/c transferred either with CD4+, CD8+, or both T cell subsets. Nontransferred (NT) and uninfected (UI) mice were included as controls. Data shown are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 between nontransferred and transferred mice, Student's t test. NS indicates nonsignificant.

Furthermore, a significant increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing the early activation marker CD69 was observed only in cell suspensions derived from mice immunized with BCG-N or BCG-M2 after stimulation with recombinant N or M2 proteins, respectively (Fig. 6B). Expression of IFN-γ could be detected in these CD4+ T cells expressing CD69 (Fig. 6C). In contrast, no increase in CD4+ T cells expressing CD69 or IFN-γ was observed in unimmunized mice or mice immunized with WT-BCG or UV-RSV (Fig. 6B and data not shown).

To confirm that protection against RSV was mediated by virus-specific T cells induced by immunization with recombinant BCG, adoptive transfer experiments were performed. Purified CD8+ and CD4+ T cells obtained from mice immunized with BCG-N were adoptively transferred into naive BALB/c mice. One day after the transfer, mice were challenged with RSV as described in Methods. As shown in Fig. 6D, mice that received either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from BCG-N-immunized mice were only partially protected against RSV infection, as shown by a less severe weight loss (Fig. 6D) and neutrophil airway infiltration (Fig. 6D) after virus challenge. In contrast, complete protection against RSV challenge was obtained after the simultaneous transfer of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from BCG-N-immunized mice. Mice receiving both T cell populations showed neither weight loss nor neutrophil airway invasion after RSV infection, appearing equivalent to uninfected animals. In contrast, no protection was seen for nontransferred mice. These results support the notion that T cell-mediated immune response induced by immunization with recombinant BCG is required to protect against RSV. As an additional control, RAG-deficient BALB/c mice (lacking T and B cells) were immunized with BCG-N and challenged with RSV 21 days later. In these experiments RSV-infected mice showed equivalent weight loss and recruitment of inflammatory cells into the airways compared with unimmunized mice (Fig. S3).

Taken together, the above data suggest that immunization with recombinant BCG strains expressing RSV antigens promotes the activation of T cells with a Th1-like pattern of cytokine secretion. This type of T cell immunity could be responsible for the protection observed upon RSV challenge and conferred through immunization with recombinant BCG.

Discussion

The severe symptoms that RSV infection can cause in infants are responsible for a major public health burden and have an extremely high socioeconomic impact worldwide. Research efforts are needed to promote the design of safe, effective, and affordable vaccines capable of protecting against infection caused by RSV. This goal has turned out to be difficult, in part due to the virulence factors displayed by RSV, as well as the immunological component of the pathogenesis induced by this virus (38, 39). Several independent studies have shown that RSV can modulate the host immune response in at least 2 different ways. First, RSV seems to block the activation, expansion, and function of cytotoxic and memory T cells specific to viral antigens. As a result, primary infection does not confer immune protection against subsequent reinfections with antigenically similar RSV strains (40–42). Another example of immune modulation is observed after RSV infection and/or vaccination with inactivated virus, which can induce a detrimental Th2 immune memory. This type of immune response can promote airway inflammation, leading to lung injury after a second exposure to RSV (11, 43). Because of the complexity of the detrimental immune response induced by RSV, more than 2 decades of research have been required to identify a potentially successful approach to generate a safe and protective vaccine against this pathogen. It has been suggested that protection against RSV could be achieved by means of immunization methods capable of promoting a balanced, RSV-specific, Th1-type immune response, which could clear viral infection without excessive or damaging inflammation of the infected tissues. Because several genetically modified RSV strains have failed to promote protective immunity even in the presence of Th1-type cytokines (7), it would seem likely that the choice of vector expressing RSV antigens is a critical parameter for conferring immune protection against the virus.

In this study we demonstrate that vaccination with recombinant BCG strains expressing RSV antigens can dampen RSV-induced disease. Moreover, recombinant BCG strains expressing RSV antigens efficiently promote protective Th1-like immunity against this virus, which fosters clearance of this pathogen with no evident inflammation and lung injury. Interestingly, it is likely that this feature is a consequence related directly to BCG and its capacity to promote a balanced Th1 immune response. It is thought that the capacity of BCG to induce Th1-skewed immune responses would be in part mediated by the cell wall lypomannan and lipoarabinomannan, which promote IL-12 secretion by dendritic cells (44). It seems that this feature of BCG is fundamental for inducing a protective immune response against RSV, because vaccination with other bacterial vectors expressing the same RSV antigens, such as attenuated strains of Salmonella, failed to confer protection against the virus (Fig. S4).

BCG has been applied for several decades as a vaccine against tuberculosis (45) and, more recently, was used successfully as a carrier to promote a Th1 immune response against antigens from other bacterial and viral pathogens, such as measles (24), Borrelia (46, 47), Bordetella pertussis (48, 49), and Pneumococcus (50). In this study we show that recombinant BCG strains expressing either protein N or protein M2 from RSV can promote a cell-mediated, Th1-like, RSV-specific immune response. Our data show that vaccination with these recombinant BCG strains promotes secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 by RSV-specific T cells residing in spleens of vaccinated mice. As a result, weight loss and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways, a process induced by RSV infection, were prevented with the RSV-specific immune response induced by recombinant BCG strains. Furthermore, immunization with BCG expressing RSV proteins significantly reduced virus presence in infected lung tissue after challenge and prevented excessive lung inflammation. On the contrary, unimmunized, WT-BCG-immunized, or UV-RSV-immunized animals showed significant weight loss and inflammatory infiltration into the airways. According to previous studies, RSV-immunized mice showed enhanced inflammatory infiltration within airways and lungs compared with unimmunized animals because of the adverse Th2 immune response promoted by RSV antigens (10). It is noteworthy that after RSV infection, mice immunized with WT-BCG showed a moderate reduction in the amount of inflammatory cells infiltrating the airways. However, differences observed were not statistically significant when compared to unimmunized animals (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that BCG immunization can promote IFN-γ secretion by T cells after unspecific stimulation, and reduce allergic responses to inhaled antigens (51, 52). In addition, it has been demonstrated that immunization of newborns with BCG induces a strong Th1 immune response, despite the fact that newborns are prone to Th2 responses upon antigenic challenge (23, 53). Further, several epidemiological studies have provided evidence supporting the notion that Mycobacterium exposure can prevent atopic disorders in humans (54, 55). Nevertheless, the observation that significant weight loss followed RSV infection in mice immunized with WT-BCG would indicate that the unspecific immunity induced by BCG is not sufficient to prevent RSV-induced disease (Fig. 2A). On the contrary, our data suggest that protection against RSV requires specific T cell-mediated immunity involving CD4+ and CD8+ T cells secreting Th1-type cytokines (Fig. 6D). This notion is further supported by the observation that BCG strains expressing RSV antigens failed to confer protection to RSV in RAG-deficient mice (Fig. S3).

It is likely that pathogen-associated molecular patterns derived from recombinant BCG can modify the nature of adaptive immunity to RSV antigens by promoting a Th1-like T cell response, which can counteract the allergic-like immune response triggered by natural RSV infection. Our results support the notion that vaccination with BCG expressing RSV antigens induces a Th1 immune response, which protects against RSV infection. Considering that administration of BCG to newborns has been demonstrated to be safe, strains of BCG expressing RSV antigens are candidates for a potential new vaccine that could be administered to young children to prevent disease induced by RSV infection during infancy.

Methods

Mice and RSV Production.

BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile animal facility (Santiago, Chile). All animal work was performed according to institutional guidelines. RSV serogroup A, strain 13018-8, is a clinical isolate provided by the Public Health Institute of Chile. Sequence comparison analyses reveal that this clinical strain is 96% identical to the standard RSV long strain (Fig. S5). RSV was propagated over HEp-2 cells, as described in SI Methods. RSV preparations were routinely evaluated for lipopolysaccharide and mycoplasma contamination. Recombinant production of RSV proteins was performed as described in SI Methods.

Generation of BCG Expressing RSV Proteins and Preparation of Vaccine Doses.

BCG strains expressing the N or M2 proteins (BCG-N and BCG-M2, respectively) were generated as described in SI Methods. Expression of N or M2 proteins by BCG strains was assessed by Western blot analysis using rabbit antisera against N or M2 protein, respectively. Vaccine doses of BCG-N, BCG-M2, or nonrecombinant BCG were prepared as described in SI Methods. BCG-OVA was generated as described previously (56).

Mouse Immunization and RSV Challenge.

Four- to 6-week-old BALB/c mice (5–8 animals per group) received a subdermal injection with 1 × 108 cfu of WT-BCG, BCG-N, or BCG-M2 in the right dorsal flank. As controls, unimmunized mice or mice vaccinated with 1 × 107 pfu of UV-inactivated RSV were included in each experiment. At 7, 14, and 21 days after vaccination, serum samples were obtained from the tails of mice, and anti-N or anti-M2 antibodies (IgG) were detected by ELISA using 500 ng/well recombinant N or M2 proteins and serial dilutions of mouse sera. Twenty-one days after vaccination, mice were anesthetized with 150 μL of a 0.8% ketamine-0.1% xylazine solution in PBS and challenged intranasally with 1 × 107 pfu of RSV in 75-μL inoculums. Body weight was determined daily after vaccination and for 4 days after infection.

FACS Analyses of BAL Cells.

After 4 days of infection, mice were terminally anesthetized, and lungs were inflated through the trachea 3 times with PBS. Recovered cells were stained with trypan blue and counted with a Neubauer chamber. A total of 200 μL was spun onto glass slides, air dried, and stained with May-Grünwald and Giemsa (Merck). Visual quantification of neutrophils was performed in 6 random fields per sample on an Olympus BX51 light microscope at 40× magnification. BALs were centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min, resuspended in 100 μL of PBS, and stained with 0.1 μL of anti-CD11b-FITC and GR-1 (Ly-6G)-APC (BD PharMingen) for 30 min on ice. Data acquisition was performed on a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by using WinMDI 2.8 software (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA; http://facs.scripps.edu/help/html/read1ptl.htm).

Lung Histopathology.

Lungs of control and infected mice were removed, and the right upper lobes were frozen in Tissue Freezing Medium (Jung) at −80 °C. Five-micrometer slices were prepared on a Leica CM 1510 S cryostat and stained with hematoxylin/eosin and evaluated for HPS as described in SI Methods. RSV detection in lung tissues was performed by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, as described in SI Methods. Eosinophil infiltration was detected in 5-μm lung sections using the EoProbe staining kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioFX Laboratories) and was analyzed on a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Cytokine Secretion by RSV-Specific T Cells.

Spleen cells from unimmunized or mice immunized with WT-BCG, BCG-M2, BCG-N, or UV-RSV were obtained as described in SI Methods and incubated with 10 μg/mL of either recombinant protein N or M2. Recombinant proteins were produced as described in SI Methods. After 5 days of incubation, cytokine secretion was determined on supernatants by sandwich ELISA as described previously (57). Cytokine secretion was expressed as fold increase relative to unstimulated cells (treated only with PBS). CD69 expression and IFN-γ secretion by T cells were evaluated by flow cytometry, as described in SI Methods.

Adoptive Transfers of RSV-Specific T Cells to Naive Mice.

Spleen and lymph node cells from unimmunized mice or mice immunized with WT-BCG or BCG-N were cultured in the presence of N protein as described above. After 5 days, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were purified with CD4+ or CD8+ MACS T cell isolation kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). A total of 106 purified CD4+, CD8+, or a 1:1 mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were injected intravenously into syngeneic recipient mice. Recipient mice were challenged with 1 × 107 pfu of RSV 24 h later. Body weight was scored daily during the 5 days after infection, and BALs were analyzed for the presence of GR1+ and CD11b+ cells at day 5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. M. Ferrés (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile) for providing the RSV isolate, Dr. G. Tapia for help with CAT scan analyses, and J. P. Zúñiga and P. Bustos for technical support. This work was supported by Fondo de Fomento al Desarrollo Científico y Technológico Grant D04I1075; Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Technológico Grants 1070352, 1050979, 3060041, 11075060, and 1040349; SavinMuco-Path-INCO-CT-2006–032296; International Foundation for Science B/3764–1; and Millennium Nucleus on Immunology and Immunotherapy Grant P04/030-F. P.A.G. and H.E.T. are Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica fellows.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: A patent application on this work has been filed.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806244105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hacking D, Hull J. Respiratory syncytial virus-viral biology and the host response. J Infect. 2002;45:18–24. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mejias A, Chavez-Bueno S, Jafri HS, Ramilo O. Respiratory syncytial virus infections: Old challenges and new opportunities. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S189–S196. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000188196.87969.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang J, Braciale TJ. Respiratory syncytial virus infection suppresses lung CD8+ T-cell effector activity and peripheral CD8+ T-cell memory in the respiratory tract. Nat Med. 2002;8:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braciale TJ. Respiratory syncytial virus and T cells: Interplay between the virus and the host adaptive immune system. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:141–146. doi: 10.1513/pats.200503-022AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckham JD, et al. Respiratory viral infections in patients with chronic, obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect. 2005;50:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund JA, et al. Rapid diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus infections in immunocompromised adults. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1649–1653. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1649-1653.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harker J, et al. Virally delivered cytokines alter the immune response to future lung infections. J Virol. 2007;81:13105–13111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01544-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HW, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapikian AZ, Mitchell RH, Chanock RM, Shvedoff RA, Stewart CE. An epidemiologic study of altered clinical reactivity to respiratory syncytial (RS) virus infection in children previously vaccinated with an inactivated RS virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:405–421. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waris ME, Tsou C, Erdman DD, Zaki SR, Anderson LJ. Respiratory synctial virus infection in BALB/c mice previously immunized with formalin-inactivated virus induces enhanced pulmonary inflammatory response with a predominant Th2-like cytokine pattern. J Virol. 1996;70:2852–2860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2852-2860.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connors M, et al. Pulmonary histopathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge of formalin-inactivated RSV-immunized BALB/c mice is abrogated by depletion of CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 1992;66:7444–7451. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7444-7451.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghaddam A, et al. A potential molecular mechanism for hypersensitivity caused by formalin-inactivated vaccines. Nat Med. 2006;12:905–907. doi: 10.1038/nm1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon JS, Kim HH, Lee Y, Lee JS. Cytokine induction by respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus in bronchial epithelial cells. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:277–282. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karron RA, et al. Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1093–1104. doi: 10.1086/427813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Sobrido L, et al. Protection against respiratory syncytial virus by a recombinant Newcastle disease virus vector. J Virol. 2006;80:1130–1139. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1130-1139.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takimoto T, et al. Recombinant sendai virus expressing the G glycoprotein of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) elicits immune protection against RSV. J Virol. 2004;78:6043–6047. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.6043-6047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etchart N, et al. Intranasal immunisation with inactivated RSV and bacterial adjuvants induces mucosal protection and abrogates eosinophilia upon challenge. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1136–1144. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cyr SL, et al. Intranasal proteosome-based respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines protect BALB/c mice against challenge without eosinophilia or enhanced pathology. Vaccine. 2007;25:5378–5389. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu KF, et al. The immunomodulating properties of human respiratory syncytial virus and immunostimulating complexes containing Quillaja saponin components QH-A, QH-C and ISCOPREPTM703. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusibova V, et al. Peptide-based candidate vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus. Vaccine. 2007;23:2261–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanekom WA. The immune response to BCG vaccination of newborns. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1062:69–78. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchant A, et al. Newborns develop a Th1-type immune response to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination. J Immunol. 1999;163:2249–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fennelly GJ, Flynn JL, ter Meulen V, Liebert UG, Bloom BR. Recombinant bacille Calmette-Guérin priming against measles. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:698–705. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennehy M, Bourn W, Steele D, Williamson AL. Evaluation of recombinant BCG expressing rotavirus VP6 as an anti-rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:3646–3657. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapeah S, Norazmi MN. Immunogenicity of a recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin expressing malarial and tuberculosis epitopes. Vaccine. 2006;24:3646–3653. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medeiros MA, Armôa GRG, Dellagostin OA, McIntosh D. Induction of humoral immunity in response to immunization with recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressing the S1 subunit of Bordetella pertussis toxin. Can J Microbiol. 2005;51:1015–1020. doi: 10.1139/w05-095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cayabyab MJ, et al. Generation of CD8+ T-cell responses by a recombinant nonpathogenic Mycobacterium smegmatis vaccine vector expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env. J Virol. 2006;80:1645–1652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1645-1652.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawahara M, Matsuoa K, Honda M. Intradermal and oral immunization with recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressing the simian immunodeficiency virus Gag protein induces long-lasting, antigen-specific immune responses in guinea pigs. Clin Immunol. 2006;119:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Im EJ, et al. Vaccine platform for prevention of tuberculosis and mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through breastfeeding. Am Soc Microbiol. 2007;81:9408–9418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00707-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezende CA, De Moraes MT, De Souza Matos DC, Mcintochc D, Armoa G. Humoral response and genetic stability of recombinant BCG expressing hepatitis B surface antigens. J Virol Methods. 2005;125:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, et al. Immune response induced by recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressing ROP2 gene of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol Int. 2007;56:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang J, Choi SY, Jin HT, Sung YC, Braciale TJ. Improved effector activity and memory CD8 T cell development by IL-2 expression during experimental respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2004;172:503–508. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukens MV, et al. Characterization of the CD8+ T cell responses directed against respiratory syncytial virus during primary and secondary infection in C57BL/6 mice. Virology. 2006;352:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stark JM, et al. Genetic susceptibility to respiratory syncytial virus infection in inbred mice. J Med Virol. 2002;67:92–100. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro SM, et al. Antioxidant treatment ameliorates respiratory syncytial virus-induced disease and lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1361–1369. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-319OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis IC, Sullender WM, Hickman-Davis JM, Lindsey JR, Matalon S. Nucleotide-mediated inhibition of alveolar fluid clearance in BALB/c mice after respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L112–L120. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00218.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culley FJ, Pennycook AM, Tregoning JS, Hussell T, Openshaw PJ. Differential chemokine expression following respiratory virus infection reflects Th1- or Th2-biased immunopathology. J Virol. 2006;80:4521–4527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4521-4527.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varga SM, Wang X, Welsh RM, Braciale TJ. Immunopathology in RSV infection is mediated by a discrete oligoclonal subset of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2001;15:637–646. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singleton R, Etchart N, Hou S, Hyland L. Inability to evoke a long-lasting protective immune response to respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice correlates with ineffective nasal antibody responses. J Virol. 2003;77:11303–11311. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11303-11311.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:693–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez PA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus impairs T cell activation by preventing synapse assembly with dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14999–15004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802555105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussell T, Spender LC, Georgiou A, O'Garra A, Openshaw PJ. Th1 and Th2 cytokine induction in pulmonary T cells during infection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2447–2455. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-10-2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito T, et al. Human Th1 differentiation induced by lipoarabinomannan/lipomannan from Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo-172. Int Immunol. 2008;20:849–860. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumann S, Nasser Eddine A, Kaufmann SH. Progress in tuberculosis vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edelman R, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of recombinant bacille Calmette-Guérin (rBCG) expressing Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein A (OspA) lipoprotein in adult volunteers: A candidate Lyme disease vaccine. Vaccine. 1999;17:904–914. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langermann S, Palaszynski S, Sadziene A, Stover CK, Koenig S. Systemic and mucosal immunity induced by BCG vector expressing outer-surface protein A of Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1994;372:552–555. doi: 10.1038/372552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nascimento IP, et al. Neonatal immunization with a single dose of recombinant BCG expressing subunit S1 from pertussis toxin induces complete protection against Bordetella pertussis intracerebral challenge. Microbes Infect. 2007;10:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nascimento IP, et al. Recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressing pertussis toxin subunit S1 induces protection against an intracerebral challenge with live Bordetella pertussis in mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4877–4883. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.4877-4883.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langermann S, et al. Protective humoral response against pneumococcal infection in mice elicited by recombinant bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccines expressing pneumococcal surface protein A. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2277–2286. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vonberg RP, Mueller M, Emmendoerffer A, Freihorst J. Influence of immunisation with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin on the sensitisation to inhaled allergens after infection with respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Exp Med. 2005;5:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s10238-005-0083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walzl G, et al. Prior exposure to live Mycobacterium bovis BCG decreases Cryptococcus neoformans-induced lung eosinophilia in a gamma interferon-dependent manner. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3384–3391. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3384-3391.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barrios C, et al. Neonatal and early life immune responses to various forms of vaccine antigens qualitatively differ from adult responses: Predominance of a Th2-biased pattern which persists after adult boosting. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1489–1496. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Mutius E, et al. International patterns of tuberculosis and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema. Thorax. 2000;55:449–453. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.6.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirakawa T, Enomoto T, Shimazu S, Hopkin JM. The inverse association between tuberculin responses and atopic disorder. Science. 1997;275:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinchey J, et al. Enhanced priming of adaptive immunity by a proapoptotic mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2279–2288. doi: 10.1172/JCI31947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bueno SM, et al. The capacity of Salmonella to survive inside dendritic cells and prevent antigen presentation to T cells is host specific. Immunology. 2008;124:522–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.