Abstract

During the development of cerebral cortex, newborn pyramidal neurons originated from the ventricle wall migrate outwardly to the superficial layer of cortex under the guidance of radial glial filaments. Whether this radial migration of young neurons is guided by gradient of diffusible factors or simply driven by a mass action of newly generated neurons at the ventricular zone is entirely unknown, a potential guidance mechanism that has long been overlooked. Our recent study showed that a guidance molecule semaphorin-3A, which is expressed in descending gradient across cortical layers, may serve as a chemoattractive guidance signal for radial migration of newborn cortical neurons toward upper layers. We hypothesize the existence of four groups of extracellular factors that can guide the radial migration of young neurons: (1) attractive factors expressing in superficial layers of cortex, (2) repulsive factors enriched in the ventricular zone, (3) pro-migratory factors uniformly expressed in all cortical layers and (4) stop signals locally expressed in the outmost layer of cortex.

Key words: radial migration, cortex, guidance, semaphorin, diffusible factors, growth cone

The mammalian cerebral cortex has the typical laminar structure, the formation of which is essential for neurons in each cortical layer to establish the specific input and output connections with other brain regions. The development of the cortical laminar structure is known to involve the well-coordinated radial migration of newborn pyramidal neurons during development.1 After young neurons are generated from the ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ), they leave their birthplace and migrate along radial glial filaments toward the surface of cortical plate (CP), crossing existing cortical layers composed of earlier born neurons and eventually settling down beneath the marginal zone (MZ, layer I).1–3 It is generally accepted that the adhesion between neurons and radial glial filaments provides the directionality for these young neurons, and the targeting of neurons to specific lamina was controlled by the selective detachment of migrating neurons from radial glial fibers upon reaching the designated cortical layer.2,3 However, we believe that the radial glial fibers can only serve as the adhesive scaffold for migrating neurons and constrain their migration in the radial dimension; it remains an open question regarding the nature of the signals that cause newborn neurons to migrate consistently outward along the fiber rather than inward. Whether the radial migration of cortical neurons is guided by gradient of diffusible factors or simply driven by a mass action of newly generated neurons at the VZ is entirely unknown, a potential guidance mechanism that has long been overlooked.

Recently we found that the radial migration of layer II/III cortical neurons during development is guided by an extracellular guidance molecule semaphorin-3A (Sema3A).4 We observed that Sema3A is expressed in a descending gradient across the cortical layers, whereas its receptor neuropilin-1 (NP1) is expressed at a high level in migrating neurons. By in utero electroporation, we were able to monitor the migration of a subpopulation of cortical neurons in their native environment and examine the effect of perturbing Sema3A signaling. We found that downregulation or conditional knockout of NP1 in young neurons impeded their radial migration with severe misorientation of affected neurons during their migration without altering their cell fate. Studies in cultured cortical slices further showed the requirement of the endogenous gradient of Sema3A for the proper migration of newborn neurons. Results from transwell chemotaxis assays in dissociated culture of newborn cortical neurons also supported the notion that Sema3A attracts the migration of these neurons through the receptor NP1. Thus, Sema3A may serve as a chemoattractive guidance signal for the radial migration of newborn cortical neurons toward upper layers. This is the first demonstration that radial migration of cortical neurons is guided by gradient of extracellular guidance factors. This study also suggests that guidance factors may guide the radial migration by their actions on the growth cone of the leading process of migrating neurons, via mechanisms similar to that found for their actions on axon guidance and dendritic orientation, followed by long-range cytoplasmic signaling that coordinates the forward motility of the entire neuron.5

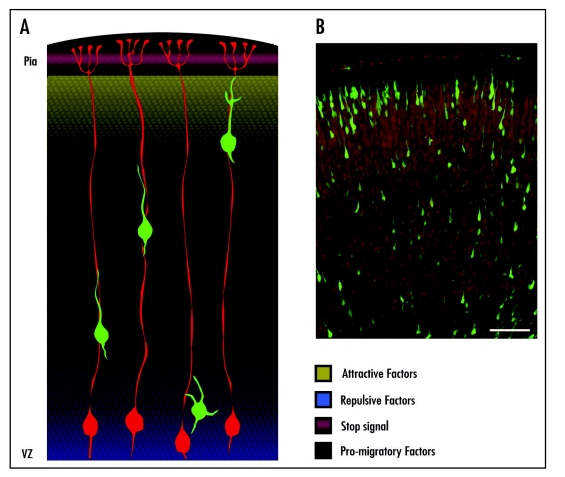

In this study, we have only observed an attractive effect of Sema3A in the radial migration of the layer II/III cortical neurons. However, to form the highly ordered laminar structure of the cortex, the entire process of neuronal migration is likely to depend on coordinated actions of multiple factors in the developing cortex, including other semaphorin family members and other guidance molecules, e.g., slits6 and ephrins,7 which are also expressed in the CP. We hypothesize that four groups of extracellular factors orchestrate to promote the proper radial migration and cortical lamination: (1) factors that are expressed in superficial layers of cortex and in a descending gradient, like Sema3A, may attract the upward migration of newborn neurons (attractive factors), (2) factors enriched in the VZ may exert repulsive action and help to “push” newborn neurons out of their birthplace (repulsive factors), (3) those factors widely expressed in all cortical layers may promote the motility of migrating neurons (pro-migratory factors) and (4) Some repulsive cues may be locally expressed in the superficial layer of cortex to prevent the over migration of neurons when they have arrived at the outmost layer (stop signal). Under the guidance of these four groups of factors, newborn neurons migrate all the way from VZ to the outmost layer of CP and then settle down. One of our recent tasks is to try to identify these four groups of factors.

If the radial migration and cortical lamination are guided by diffusible factors, why is radial glial system necessary for this migration process? In other words, why earlier-born neurons in different layers cannot provide the supportive adhesion to young neurons during their radial migration? A potential explanation is that neurons in cortex undergo maturation after terminating their migration, accompanying with changes in their expression profiles of adhesion ligands, and become less and less supportive to the neuronal migration. In contrast, as a kind of cortical progenitor cells, radial glial cells maintain a relatively ‘young’ state and continue to express supportive adhesion ligands over a very long developmental stage. Thus, only the radial glial filament is capable of providing a bridge for newborn neurons to migrate over a very long distance across the non-permissive cell layers. In summary, we believe that during the cortical radial migration, signals from diffusible factors override the adhesive signal from radial glial fibers to promote the appropriate migration and placement of newborn neurons.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram for the guidance of cortical radial migration by diffusible factors. (A) A model for the distribution of four groups of guidance factors in developing cortex. Radial glial filaments are shown in red, young neurons are in green. There may exist a descending gradient of attractive factors in upper cortical layers (yellow) and an ascending gradient of repulsive factors (blue) near the ventricular zone (VZ). Stop signals (purple) may come from the surface of cortex, and pro-migratory factors (dots) may be widely distributed. (B) Representative image of EGFP-labeled neurons migrating along radial glial filaments in the cortical tissue of E20 mouse. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (Red). Scale bar, 100 µm.

Acknowledgements

We thank Y.F.L. for help in drawing the figure. X.B.Y. was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30300103) and Shanghai government (06QH14017).

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/6001

References

- 1.Rakic P, Lombroso PJ. Development of the cerebral cortex. I. Forming the cortical structure. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:116–117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakic P. Modes of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:61–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic P. Neurons in the monkey visual cortex: systematic relationship between time of origin and eventual disposition. Science. 1974;183:425–427. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4123.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G, Sima J, Jin M, Zheng W, Wang KY, Xue XJ, Ding YQ, Yuan XB. Semaphorin-3A guides radial migration of cortical neurons during development. Nature Neurosci. 2008;11:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nn2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan CB, Xu HT, Jin M, Yuan XB, Poo MM. Long-range Ca2+ signaling from growth cone to somamediates reversal of neuronal migration induced by slit-2. Cell. 2007;129:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitford KL, Marillat V, Stein E, Goodman CS, Tessier Lavigne M, Chédotal A, Ghosh A. Regulation of cortical dendrite development by Slit-Robo interactions. Neuron. 2002;33:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebl DJ, Morris CJ, Henkemeyer M, Parada LF. mRNA expression of ephrins and Eph receptor tyrosine kinases in the neonatal and adult mouse central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:7–22. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]