Abstract

Methods are presented to separate 16 frequently occurring cancer symptoms measured on 10-point symptom severity rating scales into mild, moderate, and severe categories that are clinically interpretable and significant for use in oncology practice settings. At their initial intervention contact, 588 solid tumor cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy reported severity on a standard 11-point rating scale for 16 symptoms. All reporting a 1 or higher were asked to rate on an 11-point scale how much the symptom interfered with enjoyment of life, relationship with others, general daily activities, and emotions. Factor analysis revealed that these items tapped into the same dimension, and the items were summed to form an interference scale. Cut-points for mild, moderate and severe categories of symptom severity were defined by comparing the differences in interference scores corresponding to each successive increases in severity for each symptom. The cut-points differed among symptoms. Pain, fatigue, weakness, cough, difficulty remembering, and depression had lower cut-points for each category compared to other symptoms. Cut-points for each symptom were not related to site or stage of cancer, age, or gender but were associated with a global depression measure. Cut-points were related to limitations in physical function, suggesting differences in the quality of patients’ lives. The resulting cut-points summarize severity ratings into clinically significant and useful categories that clinicians can use to assess symptoms in their practices.

Keywords: Symptom severity cut-points, symptoms and quality of life, symptom measures

Introduction

Cancer pain has been the model for symptom assessment. To derive meaningful classifications of pain severity from 0–10 point rating scales, patients’ reports of each severity level have been paired with ratings on how pain interferes with their lives. Anchoring patients’ reports of pain severity to differences in interference cut-points for mild, moderate, and severe categories of pain have proven to be valuable for research and clinical practice [1–4]. These categories form more stable referents than each severity score alone, are more amenable to clinical interpretation, and can be used to gauge the impact of pharmacological or behavioral interventions for pain management [5–7].

This measurement model can be used to establish interference-based severity cut-points for 16 prevalent cancer symptoms. Once cut-points are established for each symptom, they can be used to assess the differences in mean interference, symptom severity, and levels of physical function for patients in the mild, moderate, and severe categories. The mean symptom severity and physical function scores among patients not reporting each symptom can be compared with patients reporting that symptom and assigned to the mild, moderate, and severe categories. Age, gender, level of depression, or site or stage of cancer can be assessed as potential predictors of patients’ assignments to mild, moderate, or severe categories.

Review of Literature

The 11-point scale used by the American Pain Society became part of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of cancer pain [8]. Later, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [9] extended the use of the scale to measure other cancer related symptoms. Validity and reliability of this methodology have undergone considerable evaluation [10], with few variations reported by sex or age [1–3]. The need to establish categories of severity was based on the recognition that patients are likely to use the lower, middle, and higher sections of the 0–10 point scale differently [1, 11].

Anchoring severity to greater decrements in the quality of patients’ lives was viewed as a more reliable and easily interpretable approach for clinical use. The Brief Pain Inventory [12] is a widely used instrument that assesses sensory (severity) and reactive (interference) dimensions of pain. Four dimensions of pain severity (worst, least, average, and pain right now) are assessed, along with how pain interfered with general activities, mood, walking, normal work, relations with others, enjoyment of life and sleep [13].

To establish interference-based severity cut-points, ratings on the multiple dimensions of interference (general activities, mood, walking normal work, relations with others, enjoyment of life, and sleep) were organized into a multi-dimensional outcome, and differences were compared among groups of patients created by various cut-points on severity scales [1–2]. The largest differences in interference scores were used to separate moderate from mild and severe from moderate categories.

Serlin et al. [1] reported the greatest values of the test statistics for differences in interference scores were for 1–4 mild pain, 5–6 moderate pain, and 7–10 severe pain. Paul et al.’s results [2] were different: cut-points for moderate and severe pain were 5–7 and 8–10, respectively; severe pain, mild pain remained 1–4. The cut-points established by Serlin et al. were sustained for worst pain and were reproduced when applied to a community-based sample [14]. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that pain severity could be reliably divided into mild, moderate, and severe according to how patients paired their severity with interference scores. This is a first step toward documenting clinically meaningful change in symptom management trials [6,15,16].

In this work, we extend this methodology to determine if cut-points based upon the association between interference and severity can be extended to 16 cancer-related symptoms using appropriate analytical approaches.

Methods

This research is based on data from two large randomized clinical trials that test the effect of cognitive behavioral interventions to assist cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy to better manage symptoms. Institutional Review Boards of two comprehensive cancer centers, one community cancer oncology program, and six hospital-affiliated community oncology centers approved this research. Nurses from clinical trials offices implemented the recruitment protocol.

To be eligible, patients met the following requirements: 1) 21 years of age or older, 2) a diagnosis of a solid tumor cancer or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 3) undergoing a course of chemotherapy, 4) speak and read English, and 5) have a touchtone telephone. Patients with a family member who agreed to assist them (a caregiver) and who signed a consent form were included.

Prior to entry into the trial, patients were screened for symptom severity using M.D. Anderson symptom inventory [13]. All patients were called twice weekly for up to six weeks. Patients scoring 2 or higher on severity of at least one symptom (range 0–10) at any contact were entered into trial. Patients never reaching a 2 were sent a letter thanking them for participation.

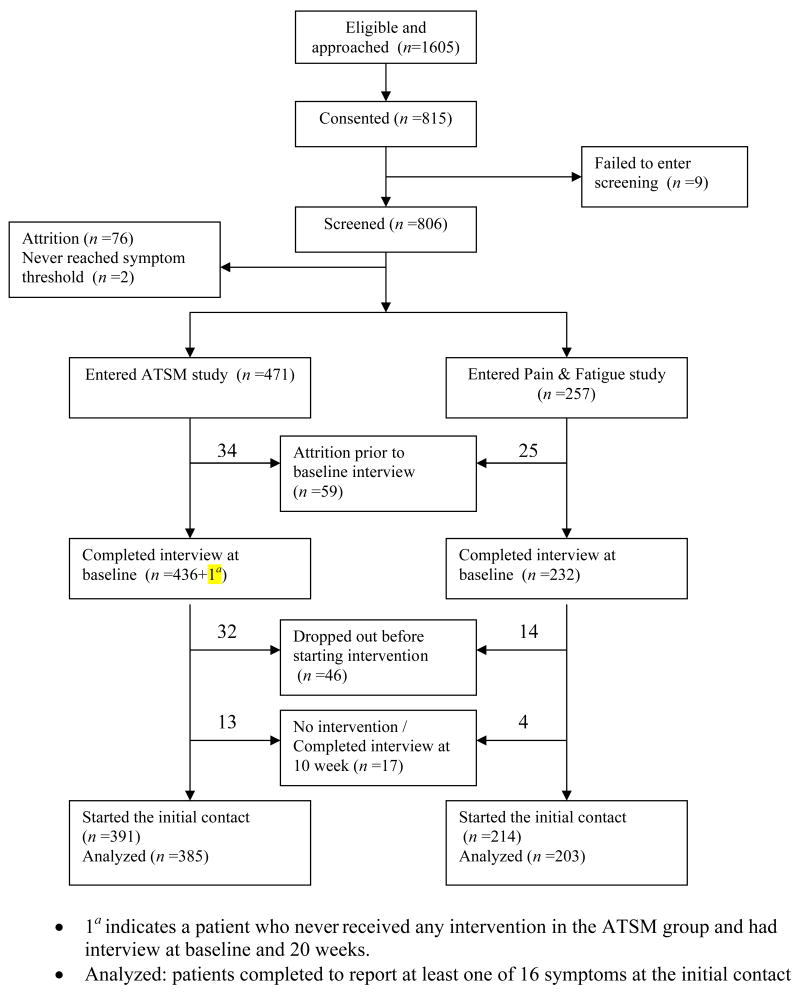

Patients who scored 2 or higher completed an intake interview, received a copy of the Symptom Management Guide (SMG), and were randomized into a six-contact eight-week trial. In one trial, patients with caregivers received either a nurse-administered intervention or an intervention delivered by a non-nurse social worker. In the second trial, patients with no caregiver received a six-contact eight-week intervention delivered by nurses or an interactive voice response arm. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of patients from eligibility through to randomization and completion of their initial intervention contact. Data collected at the first intervention contact (prior to the intervention delivery) are used in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient accrual and retention for the trials.

Measures

The four arms of the two trials shared identical assessments. Age, gender, the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) [17] and the physical function subscale of the SF-36 were assessed at intake interview. Patient responses to CES-D items are assessed using a 0–3 scale with total measure ranging from 0 to 60. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.92 in this sample. Physical function was assessed using the 10-item physical function subscale from the SF-36, a widely used instrument that measures eight dimensions of quality of life. This measure standardizes scores on a 0 to 100 scale with higher scores representing better physical function [18]. Site and stage of cancer were obtained from the patients’ medical records.

At the initial intervention contact, an 11-point severity scale was used to rate the severity of 16 symptoms: alopecia, anxiety, poor appetite, constipation, cough, depression, diarrhea, dry mouth, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, peripheral neuropathy, difficulty remembering, sleep disturbances, and weakness. For each symptom present (severity score >0), patients rated on an 11-point scale the extent to which that symptom interfered with their enjoyment of life, social relationships, general daily activities, emotions, and sleep. These interference dimensions were selected from the Brief Pain Inventory [12] when the study was designed, and assessed prior to the administration of intervention strategies.

Development of the Interference Scale

Four of the interference items were highly and positively correlated. Sleep was weakly correlated with the other four items and, based on exploratory factor analysis, appeared to tap into a different dimension. Therefore, sleep was eliminated from the total interference score. The remaining four items were submitted to an exploratory factor analysis. For each of the 16 symptoms, the factor with the largest eigenvalue explained between 70% and 90% of the total variance, and all items had approximately equal (high) loadings on this factor. Therefore for each symptom, a single four item scale was used to assess interference and develop severity cut-points. Using a single summed interference score to reflect the reactive dimension of symptom experience has been shown to be valid and reliable [19].

Data Analyses

Establishing Severity Cut-Points for Each Symptom

To identify the optimal cut-points separating mild from moderate, and moderate from severe symptom severity categories, the differences in the sum of interference items across all possible three category splits of each symptom’s severity were tested. Because the individual interference items and the summed interference scores were not normally distributed, consideration was given to how best to address these skewed distributions. We employed the generalized linear model using PROC GENMOD with gamma link function in SAS version 9.1 [20]. The likelihood ratio (LR) test of the model represents how much groups defined by the severity levels differ on the interference scores. We selected cut-points separating moderate from mild and severe from moderate by comparing the size of the LR across the severity scores for each symptom. Even though symptom-specific interference items were assessed (e.g., how much fatigue interfered with general activity), we investigated and adjusted for the possible effect of the number of other symptoms a patient was experiencing. The model that related the summed interference score to the severity categories was run with and without the number of other symptoms reported by patients a covariate. The means of the interference scores by category, both unadjusted and adjusted [21] for the number of other symptoms, were evaluated.

To determine the role of patient’s age, gender, site and stage of cancer and depression, ordinal logistic regression models using PROC LOGISTIC in SAS version 9.1 [20] were applied to investigate the association between patients’ assignments to the mild, moderate and severe categories, and these variables. The proportional odds assumption was tested using score tests for each symptom.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 588 patients who completed intake interviews and the initial intervention contact. More women than men agreed to participate in the trials. Based on the CES-D cutoff scores of less than 16, and 16 or greater, approximately one-third of the patients qualified as being at risk for clinical depression. Cancer sites in order of prevalence were: breast, lung, and colon followed by genitourinary 7%, gastrointestinal 4%, gynecological 7.6%, pancreatic 3.4%, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma 6%, myeloma 1.4%, other 3.6%. For summed symptom severity, fairly large standard deviations and means greater than medians reflect the skewed distribution.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristics | n | % | Symptom Severity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | |||

| Age | |||||

| 25 – 44 | 80 | 13.61 | 33.06 | 32.00 | 19.19 |

| 45 – 54 | 159 | 27.04 | 34.64 | 32.00 | 21.69 |

| 55 – 64 | 196 | 33.33 | 28.70 | 26.00 | 18.12 |

| 65 – 74 | 99 | 16.84 | 28.94 | 28.00 | 17.58 |

| 75 + | 54 | 9.18 | 25.46 | 23.00 | 17.44 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 175 | 29.76 | 26.72 | 24.50 | 17.20 |

| Female | 413 | 70.24 | 32.25 | 30.00 | 19.98 |

| Depression (CESD) | |||||

| 1 – 15 | 379 | 65.91 | 24.15 | 23.00 | 14.08 |

| 16 + | 196 | 34.09 | 43.55 | 40.00 | 21.47 |

| Cancer Site | |||||

| Breast | 210 | 35.7 | 33.04 | 30.50 | 20.42 |

| Colon | 67 | 11.4 | 23.33 | 18.00 | 16.53 |

| Lung | 118 | 20.1 | 30.97 | 28.00 | 19.78 |

| Other | 193 | 32.8 | 30.28 | 27.00 | 18.26 |

| Cancer Stage | |||||

| Early | 86 | 14.7 | 33.24 | 31.00 | 20.60 |

| Late | 497 | 85.3 | 30.22 | 27.00 | 19.18 |

SD = standard deviation; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale.

The cut-points obtained from the models that included and did not include the number of other symptoms were virtually identical. Table 2 summarizes the cut-points determined from the model that adjusts for the number of other symptoms. Also, we present unadjusted and adjusted mean interference scores, the mean severity of all other symptoms, and physical function scores for patients reporting each symptom at mild, moderate, and severe levels. Measures of physical function were administered in the baseline interview which occurred, on average, one week prior to the initial intervention contact.

Table 2.

Cut-points for Severity Categories, Number of Cases Reporting Each Symptom, Unadjusted Adjusted Mean Interference, Severity of Other Symptoms, and Physical Function

| Severity Category

|

Do not report a symptom | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

|

Alopecia

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 | 2 – 5 | 6 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 54 | 101 | 112 | 67 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 2.3 (4.8) | 5.0 (6.8) | 8.7 (9.2) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 2.3 (1.1) | 5.0 (1.1) | 8.6 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 28.4 (15.7) | 30.1 (17.6) | 32.6 (20.0) | 29.2 (21.1) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 58.5 (27.9) | 54.5 (27.6) | 56.7 (27.1) | 55.6 (27.9) |

|

| ||||

|

Anxiety

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 5 | 6 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 172 | 97 | 66 | 99 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 7.1 (6.3) | 13.5 (7.2) | 23.5 (8.2) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 7.2 (1.1) | 13.4 (1.1) | 22.6 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 28.5 (14.2) | 36.6 (16.3) | 49.4 (22.7) | 20.5 (12.4) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 59.2 (27.3) | 54.0 (25.8) | 46.2 (25.6) | 61.4 (26.4) |

|

| ||||

|

Poor appetite

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 6 | 7 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 119 | 115 | 70 | 110 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.8 (4.9) | 9.2 (8.1) | 16.3 (11.2) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.8 (1.1) | 9.0 (1.1) | 15.6 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 27.3 (15.9) | 34.5 (17.9) | 45.7 (21.3) | 21.2 (14.1) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 61.5 (26.3) | 51.6 (26.7) | 43.8 (26.4) | 63.0 (25.9) |

|

| ||||

|

Constipation

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 6 | 7 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 106 | 66 | 43 | 99 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 2.7 (4.0) | 6.7 (6.9) | 16.3 (10.5) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 2.7 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.1) | 15.3 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 28.5 (17.2) | 35.3 (17.2) | 46.9 (21.2) | 27.6 (18.7) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 62.2 (26.3) | 56.7 (28.7) | 49.3 (28.2) | 58.6 (25.5) |

|

| ||||

|

Cough

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 2 | 3 – 4 | 5 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 106 | 60 | 50 | 88 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 1.2 (2.1) | 5.3 (6.5) | 11.5 (8.1) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 1.2 (1.1) | 4.5 (1.1) | 10.4 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 27.2 (18.4) | 35.2 (18.6) | 41.8 (18.3) | 30.7 (19.4) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 57.1 (26.4) | 47.0 (27.4) | 53.2 (27.8) | 60.0 (26.4) |

|

| ||||

|

Depression

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 | 2 – 3 | 4 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No of cases, n (%) | 46 | 105 | 106 | 105 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.7 (3.8) | 7.8 (6.4) | 19.0 (9.6) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.5 (1.1) | 8.1 (1.1) | 18.2 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 31.1 (16.3) | 29.8 (13.8) | 47.8 (19.6) | 26.6 (14.1) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 61.8 (27.7) | 56.8 (27.3) | 45.3 (26.0) | 51.1 (25.5) |

|

| ||||

|

Diarrhea

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 5 | 6 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n(%) | 78 | 31 | 28 | 112 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.5 (5.9) | 7.3 (7.0) | 20.3 (10.9) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.2 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.2) | 19.3 (1.2) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 27.4 (17.0) | 31.7 (25.2) | 45.3 (23.0) | 31.5 (18.8) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 60.4 (27.3) | 60.3 (26.3) | 51.8 (29.1) | 54.6 (24.8) |

|

| ||||

|

Dry mouth

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 4 | 5 – 6 | 9 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 192 | 95 | 14 | 101 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 1.3 (2.6) | 5.2 (7.0) | 13.1 (11.8) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 1.2 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.1) | 10.9 (1.3) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 28.5 (17.3) | 38.4 (20.0) | 51.1 (29.6) | 25.5 (15.1) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 62.9 (25.3) | 47.8 (28.3) | 37.9 (21.6) | 56.6 (27.7) |

|

| ||||

|

Dyspnea

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 2 | 3 – 6 | 7 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 68 | 121 | 24 | 87 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 4.0 (5.5) | 10.3 (7.7) | 25.8 (9.7) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 4.0 (1.1) | 10.3 (1.1) | 25.0 (1.2) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 27.3 (15.3) | 35.4 (18.4) | 56.8 (27.1) | 28.0 (17.9) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 59.4 (23.9) | 46.4 (22.3) | 35.2 (29.5) | 58.6 (26.8) |

|

| ||||

|

Fatigue

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 | 2 – 4 | 5 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 33 | 227 | 266 | 53 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.3 (3.9) | 8.8 (6.7) | 18.3 (9.3) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.8 (1.1) | 8.7 (1.0) | 17.3 (1.0) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 13.3 (10.2) | 22.1 (12.9) | 34.5 (19.3) | 14.5 (12.0) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 77.0 (21.6) | 61.9 (24.6) | 48.4 (26.4) | 73.7 (22.7) |

|

| ||||

|

Nausea/Vomiting

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 6 | 7 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 64 | 55 | 55 | 126 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 4.1 (6.7) | 8.7 (7.0) | 21.9 (10.9) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 4.1 (1.1) | 8.7 (1.1) | 20.9 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 28.2 (15.6) | 36.2 (18.2) | 50.7 (23.0) | 30.0 (16.5) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 60.1 (30.2) | 58.7 (22.2) | 53.9 (26.8) | 53.1 (26.9) |

|

| ||||

|

Pain

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 | 2 – 4 | 5 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 28 | 118 | 108 | 127 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.3) | 9.1 (7.6) | 20.8 (10.3) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.4 (1.1) | 9.1 (1.1) | 20.0 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 26.0 (16.7) | 29.3 (14.4) | 42.5 (20.9) | 24.1 (15.1) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 66.3 (23.9) | 49.5 (25.6) | 48.9 (27.8) | 63.1 (24.2) |

|

| ||||

|

Peripheral Neuropathy

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 7 | 8 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 131 | 81 | 22 | 101 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 1.9 (4.1) | 7.9 (7.2) | 15.1 (8.5) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 1.7 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.1) | 14.2 (1.2) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 25.9 (17.4) | 34.9 (18.2) | 46.4 (29.2) | 31.9 (19.4) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 63.0 (25.1) | 51.6 (27.6) | 35.9 (30.1) | 59.1 (24.9) |

|

| ||||

|

Remembering

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 | 2 – 4 | 5 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 38 | 148 | 67 | 94 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 1.5 (2.4) | 3.9 (4.7) | 13.1 (8.9) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 1.7 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 12.1 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 24.0 (19.1) | 32.8 (18.2) | 44.0 (23.0) | 26.8 (16.4) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 63.0 (27.1) | 53.9 (24.1) | 48.0 (26.3) | 57.7 (27.5) |

|

| ||||

|

Sleep disturb

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 3 | 4 – 6 | 7 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 124 | 125 | 82 | 120 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.1) | 8.9 (7.4) | 16.5 (10.3) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 3.5 (1.1) | 8.7 (1.1) | 14.9 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 24.6 (14.5) | 30.2 (15.8) | 43.1 (23.4) | 26.1 (17.3) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 61.1 (25.8) | 59.0 (26.3) | 49.0 (26.0) | 57.4 (26.8) |

|

| ||||

|

Weakness

| ||||

| Cut-point based on interference score | 1 – 2 | 3 – 4 | 5 – 10 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| No. of cases, n (%) | 92 | 113 | 145 | 89 |

| Unadjusted Interference Mean (SD) | 4.7 (4.4) | 7.9 (6.5) | 18.0 (9.9) | - |

| Adjusted Interference Mean (SE) | 4.9 (1.1) | 7.6 (1.1) | 17.0 (1.1) | - |

| Severity of Other Symptoms Mean (SD) | 23.1 (14.7) | 29.1 (12.4) | 40.8 (20.5) | 21.9 (13.5) |

| Physical Function Mean (SD) | 67.0 (23.0) | 54.0 (22.4) | 39.8 (24.9) | 62.4 (24.3) |

SD = standard deviation; SE = standard error.

While some differences were observed in the unadjusted and adjusted mean interference scores for mild, moderate and severe symptom categories, these differences were small. Only one symptom, dry mouth, had a difference of more than two points between unadjusted and adjusted means in the severe category. However, this category has the smallest number of observations (14) compared to all other symptom categories. For most symptoms severity scores greater than 6 or 7 represent severe categories. However, for some symptoms the cut-points between moderate and severe were lower: for depression it was between 3 and 4, for pain, fatigue, weakness, cough, and difficulty remembering it was between 4 and 5. Depression, pain, fatigue, and difficulty remembering also had a low cut-point of between 1 and 2 for mild versus moderate severity. Considering that cut-points were based on how the symptom interfered with aspects of patients’ lives, it is not surprising that cough, depression, fatigue, pain, difficulty remembering, and weakness all have severe cut-points at a 5 with depression at a 4. It is reasonable that greater interference would be generated by these symptoms at lower severity levels.

In addition to where the cut-points lie for each symptom, it is instructive to compare the mean interference scores for each category. For anxiety, diarrhea, dyspnea, nausea/vomiting, and pain, the mean interference scores for the severe categories were the highest, exceeding 20 on the scale ranging from 0 to 40). The mean severity scores for all patients who did not report the symptom were compared with the mean severity for those who reported that symptom. Patients who did not report anxiety, depression and poor appetite at their initial intervention contact had mean severity scores 4.6 or more points lower than the mean severity reported by patients in the mild category suggesting that presence of these symptoms even at a mild level are associated with higher severity of other symptoms.

The physical function scores were not used in determining the cut-points for symptom severity. The differences in physical function scores among patients classified as having mild, moderate, and severe symptoms provide evidence of validity of the established cut-points. Patients with severe shortness of breath had the lowest level of physical function followed by those with peripheral neuropathy, dry mouth, and weakness. For all symptoms except alopecia, cough, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting mean physical function scores differed by more than 10 points between mild and severe categories. While patients in severe category of dry mouth had low interference scores, presence of moderate or severe versus mild dry mouth resulted in a 16 point drop in mean physical function score.

Considering that three of the items comprising the interference scale were enjoyment of life, interference with relationships, and emotions, we examined the plots for these items against severity scores for anxiety and depression to determine if one or more of these items tapping the psychological aspects of interference had a different relationship with severity scores. All four of the interference items were tightly clustered across the range of symptom severity for anxiety and depression indicating that no one or two items was contributing disproportionately to the relationship between severity and interference.

Finally, patients’ reports of mild, moderate, and severe categories for each symptom could not be predicted in any consistent manner by cancer site (lung versus non-lung), stage (early versus late), gender and age [Data not shown]. When depression scores at intake were divided into 15 and lower versus 16 or higher (an indicator of clinical depression), the higher depression category was, with the exception of alopecia, diarrhea, dry mouth, and constipation, a consistent predictor of patients being located in a higher severity category.

Discussion

This research established interference-based severity cut-points for 16 prevalent symptoms reported by patients with solid tumor cancers undergoing chemotherapy. The cut-points for classifying severity followed accepted approaches [19] by developing and testing a four-item interference scale, and testing the magnitude of the difference in interference by groups of patients with different reported levels of severity [1,2, 22]. The interference scale was unidimensional and possessed high levels of internal consistency for all symptoms. Applying this measure of interference to establish mild, moderate, and severe cut-points for the 16 symptoms enables us to extend interpretations of patient reported severity in several ways. First, interference-based cut-points separating severe from moderate depression, pain, fatigue, weakness, cough, and difficulty remembering, suggest that patients recognize how these symptoms interfere with their lives at lower levels of severity. For all of the above symptoms except cough, these differences are supported by the reported levels of physical function between patients falling into the severe compared with those reporting mild levels of severity. For virtually all symptoms there was at least a ten point difference in physical function scores. A difference of this magnitude is generally considered to be clinically significant [23], and supports further the clinical significance, based on physical function, of moving from the severe to mild category. The cut-points for pain and fatigue were lower than those established by others [1, 2, 22]. One of the reasons that might account for differences in cut-points for pain and fatigue is the manner in which severity was assessed. Mendoza et al. [22] used worst fatigue scores as opposed to simple rating in the past week as was done in this research. Second, analytical approaches assuming normal distributions of interference such as MANOVA could produce different cut-points when contrasted with the regression techniques employed here that are appropriate for highly skewed distributions of the interference outcomes. In our sample, not only individual interference items, but also summed interference scores followed the distributions that were skewed to the right. Finally, Mendoza et al. [22], Serlin et al. [1], and Paul et al. [2] determined cut-points for mild by comparing cut-points 3 and 4 for mild, and 7 and 8 for severe, and did not test other possible cut-points.

While cut-points established by different methods may not vary by more than one integer, the resulting interference scores might be considerably higher for the severe categories. This distinction among these symptoms should be considered when evaluating patient response levels to interventions for symptom management. Taking into consideration the magnitudes of interference for each symptom category, and how they might influence symptom responses to management trials, we argue that future work evaluate the stability of these cut-points over time and using the cut-points for symptom severity create categories of response to the management of each symptom in order to determine if novel trials are more successful with some as opposed to other symptoms. If responses are similar among each of the symptoms, then the possibility is opened for combining symptoms at the patient level.

As with other research, our results suggest that age, gender, site and stage of cancer have no reliable association with patients’ reports of mild, moderate or severe symptoms. However, the important role that depression plays in predicting higher severity categories for virtually all symptoms is not surprising. Jensen and Colleagues [24] indicated that depression was closely associated with measures of pain. Barsevick et al. [25] established a partial mediation of the relation between fatigue and functional status by the depressive symptoms. In our samples, depression levels predicted severity categories for all symptoms except alopecia, diarrhea and dry mouth.

Limitations

Several limitations deserve to be made explicit. While our sample size was adequate, it was confined to patients with solid tumors undergoing a course of chemotherapy. During the first intervention contact, patients were asked about both nausea and vomiting in one question. Separating nausea from vomiting could result in different cut-points for these symptoms.

Conclusions

This research extended the use of interference-based severity cut-points to cover 16 symptoms among cancer patients with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy. Based on the evidence presented, most symptoms shared common or close cut-points separating mild from moderate, and moderate from severe. These findings provide guidance to clinicians as they seek to understand patient reports of severity for different symptoms and the clinical significance of these differences based on how they interfere with basic activities. These evidence based categories offer a strong framework for testing and interpreting novel interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant CA79280 from the National Cancer Institute and in affiliation with the Walther Cancer Institute, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, et al. When is cancer pain mild, moderate, or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00178-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul SM, Zelman DC, Smith M, et al. Categorizing the severity of cancer pain: further exploration of the establishment of cut-points. Pain. 2005;113:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen MP, Smith DG, Ehde DM, et al. Pain site and the effects of amputation pain: further clarification of the meaning of mild, moderate, and severe pain. Pain. 2001;91:317–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelman DC, Hoffman DL, Seifeldin R, et al. Development of a metric for a day of manageable pain control: derivation of pain severity cut-points for low back pain osteoarthritis. Pain. 2003;106:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, et al. Defining the clinically important differences in pain outcome measures. Pain. 2000;88:287–294. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of chances in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionne RA, Bartoshuk L, Mogil J, et al. Individual responder analyses for pain: does one pain scale fit all? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(3):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, et al. Management of cancer pain. Clinical practice guideline No. 9. AHCPR Publication No. 94-0592. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1994. Pain in special populations; pp. 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Cancer-related fatigue version 1. [Last accessed June 28, 2006];2006 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0029. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/fatigue.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. Pain. 2003;4(1):2–21. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huskisson EC, Scott J. How double blind is double blind? And does it matter? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1976;3(2):331–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1976.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flannery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleeland C, Mendoza T, Wang X, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Mobley GM, et al. Asking the community about cut-points used to describe mild, moderate, and severe pain. J Pain. 2006;7(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowbotham MC. Editorial: What is a ‘clinically meaningful’ reduction of pain? Pain. 2001;94:131–132. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas EM, Weiss SM. Nonpharmacological interventions with chronic cancer pain in adults. Cancer Control. 2000;7(2):157–164. doi: 10.1177/107327480000700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleeland S. Assessment of pain in cancer: measurement issues. In: Foley KM, Bonica JJ, Ventafridda V, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy. Vol. 16. New York: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Software, Version 9, of the SAS System for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Searle SR, Speed FM, Miliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares means. Am Stat. 1980;34(4):216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Norman GR, Juniper EF, et al. A critical look at transition ratings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):900–908. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen P, Nielson WR, Turner JA, Romano JM, Hill ML. Readiness to self-manage pain is associated with coping and with psychological and physical functioning among patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2003;104(3):529–537. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barsevick AM, Dudley WN, Beck SL. Cancer-related fatigue, depressive symptoms, and functional status. Nurs Res. 2006;55(5):366–372. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]