Abstract

Many bacterial appendages have filamentous structures, often composed of repeating monomers assembled in a head-to-tail manner. The mechanisms of such linkages vary. We report here a novel protein oligomerization motif identified in the FadA adhesin from the Gram-negative bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum. The 2.0 Å crystal structure of the secreted form of FadA (mFadA) reveals two antiparallel α-helices connected by an intervening 8-residue hairpin loop. Leucine-leucine contacts play a prominent dual intra- and intermolecular role in the structure and function of FadA. First, they comprise the main association between the two helical arms of the monomer; second, they mediate the head-to-tail association of monomers to form the elongated polymers. This leucine-mediated filamentous assembly of FadA molecules constitutes a novel structural motif termed the “leucine chain.” The essential role of these residues in FadA is corroborated by mutagenesis of selected leucine residues, which leads to the abrogation of oligomerization, filament formation, and binding to host cells.

Bacterial appendages, such as flagella and pili, are required for bacterial motility or adherence, thus playing an important role in bacterial interaction with the host and environment (1). These appendages are often composed of repeated monomers. The monomers are linked together via varying mechanisms and form filaments of different length and width, with some easy to detect and others not (1).

A novel adhesin protein, FadA, was recently identified from the opportunistic human pathogen Fusobacterium nucleatum (2). F. nucleatum is one of the most abundant Gram-negative anaerobes colonizing the subgingival plaque, present in both healthy and diseased periodontal sites and associated with various forms of periodontal disease (3). It has been suggested that F. nucleatum migrates from its primary site of colonization in the oral cavity to other parts of the body via hematogenous transmission. Transmission of F. nucleatum into amniotic fluid and placenta of pregnant women causes premature delivery (4). Animal studies have shown that, once in the bloodstream, F. nucleatum specifically colonizes the placenta and activates TLR4-mediated placental inflammatory responses, leading to preterm and term stillbirths and unsustained live births (5, 6). F. nucleatum binds to and invades both epithelial and endothelial cells, causing host inflammatory responses (2, 7), and FadA is required for bacterial attachment and invasion of the host cells (2, 8).

FadA is highly conserved among oral fusobacteria and is absent in the non-oral fusobacterial species (2). In recombinant Escherichia coli as well as in F. nucleatum, FadA exists in two forms. The non-secreted pre-FadA consists of 129 amino acids (Fig. 1) and is associated with the inner membrane (8). The secreted mature FadA (mFadA) 3 consists of 111 amino acids (Fig. 1) and is easily dissociated from the bacteria by washing (8). Mixtures of pre-FadA and mFadA form high molecular weight aggregates, which are required for attachment and invasion of the host cells (8).

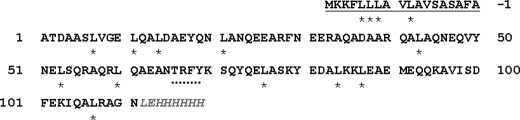

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequence of FadA in one-letter code. The underlined residues encode the signal peptide followed by mFadA. The leucine residues are marked by asterisks, the central hairpin residues TRFY are marked by dotted lines, and the histidine tag with the extra leucine and glutamic acid residues at the C terminus are italicized in gray. In all assays, the His-tagged proteins were used.

We recently crystallized the recombinant mFadA-His6 tag fusion protein (9). Here we report the crystal structure of mFadA at 2.0 Å resolution and its relation to the oligomeric antenna-like assembly observed in the electron micrographs of FadA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Construction of FadA Variants—E. coli DH5α and BL21 (DE3) were maintained as described previously (8). Plasmid pYWH417-6 carries the entire fadA gene in the pET21 (b) expression vector (Novagen, San Diego, CA), producing both mFadA and pre-FadA, each with a His tag fusion at the carboxyl end (8). The FadA variants were constructed with the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using the primers listed in supplemental Table 1 and following the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescent Staining of FadA—F. nucleatum was harvested by centrifugation and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The suspension was spotted onto a glass slide and allowed to air dry. After methanol fixation, the bacteria were first incubated with 3 mg/ml bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with anti-FadA monoclonal antibody (mAb) 5G11-3G8 (8) at 1:1,000 dilution for 30 min at 37 °C. Following washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the bacteria were incubated with FITC-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C. For controls, FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated with the bacteria without prior incubation with anti-FadA mAb.

Purification of FadA—Wild-type and variant recombinant FadA were expressed and purified from E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pYWH417-6 and its derivatives as described previously (8). For electron microscopy and tissue-culture attachment assays, pre-FadA and mFadA were co-purified under denaturing conditions without further separation (8). For crystallization and size-exclusion chromatography, mFadA was purified by washing the cells with hot phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma) followed by cobalt column purification (8).

Crystallization—All protein variants were crystallized by vapor diffusion in hanging or sitting drops at 295 K using VDX or Cryschem 24-well plates (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA). mFadA crystals were obtained as described previously (9). The crystallization conditions for the L14A variant protein form II were identical to wild-type mFadA except that the pH was 7.0. For all other variants (L14A form I and L76A), different crystallization conditions had to be established using screening kits from Hampton Research (Crystal Screens 1 and 2 or Additive Screens). Protein stock solutions of 20-30 mg/ml in 10 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, and pH 8.0 were used. Drops were prepared by mixing 1 μl of protein solution with 1 μl of reservoir solution. The best crystals were obtained in sitting drops. Diffraction quality crystals of L14A form I were obtained from 0.1 m imidazole, pH 7.5, and 0.5 m sodium acetate. Mutant L76A crystallized from 0.1 m sodium citrate, pH 5.2, 0.1% β-octylglucoside, and 0.1 m trimethylamine HCl. Crystals of the variant proteins grew within 1 week.

X-ray Data Collection and Structure Determination—For cryoprotection, crystals of wild-type mFadA and its variants (L14A and L76A) were soaked for 30-60 s in corresponding reservoir solutions supplemented with 30% (v/v) glycerol. Crystals were mounted in a cryo loop (Hampton Research) and immediately flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen for x-ray data collection on an in-house x-ray diffraction system (Bruker Proteum II) or for transport to a synchrotron radiation source. Synchrotron data were collected at beam line 4.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Berkeley, CA and at beam line BM-19 of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne, IL. Diffraction images were processed either using DENZO and SCALEPACK from the HKL2000 suite (10) or with the d*TREK package (11). Crystal parameters and data collection statistics for the best diffracting crystals are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic data

Wild-type mFadA data were collected at beam line BM-19 of the Structural Biology Center (SBC) at APS. MAD data for wild-type mFadA were collected at beam line 4.2.2 of MB-CAT at ALS. All data were collected at 100 K.

| mFadA | L14A form I | L14A form II | L76A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Properties | |||||

| Space group | P61 | P21 | P61 | P61 | |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a = b = 59.3 c = 126.4 | a = 59.3, b = 104.8 c = 59.9, β = 105.1° | a = b = 60.2 c = 82.5 | a = b = 59.5 c = 186.1 | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0332 | 0.97934 | 0.96112 | 0.97899 | |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.77 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 1.12 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 29.7-2.0 (2.07-2.0)a | 38.8-3.0 (3.11-3.0) | 32.3-2.9 (3.00-2.9) | 29.8-2.0 (2.07-2.0) | |

| Unique reflections | 15871 | 13703 | 3823 | 25094 | |

| Free reflections | 1563 | 1389 | 374 | 2459 | |

| Redundancy | 6.6 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 7.0 | |

| Completeness (%) | 93.0 (63.0)a | 97.9 (93.2) | 99.5 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.6) | |

| Average I/σ(I) | 34.3 (2.8)a | 11.6 (2.4) | 12.5 (2.0) | 23.9 (3.5) | |

| Rmerge (%)b | 4.9 (39.6)a | 9.7 (42.6) | 8.8 (45.3) | 6.7 (34.0) | |

| Refinement | |||||

| Rwork (%) | 22.5 | 23.8 | 23.8 | 22.1 | |

| Rfree (%) | 25.4 | 28.0 | 29.7 | 24.7 | |

| r.m.s. deviation bonds (Å) | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.012 | |

| r.m.s. deviation angles (°) | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.08 | |

| Number of water molecules | 162 | 102 | 20 | 208 | |

| Mean B values (Å2) | |||||

| Overall | 46.5 | 64.3/70.8/70.2c | 64.8 | 36.7/35.1c | |

| Main-chain atoms | 44.2 | 63.1/68.9/69.1c | 64.2 | 33.9/31.8c | |

| Side-chain atoms | 48.7 | 65.6/72.8/71.3c | 65.3 | 39.5/38.3c | |

| Solvent | 63.3 | 59.9 | 59.5 | 46.6 | |

| Ramachandran plot regions | |||||

| Most favored (%) | 98.1 | 94.5 | 95.0 | 98.6 | |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 1.9 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 1.4 | |

| MAD X-ray data collection statistics of a FadA crystal soaked in 1 m NaBr | |||||

| Space group | P61 | ||||

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a = b = 59.3 c = 128.3 | ||||

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.91979 | 0.91999 | 0.92871 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 33-2.3 (2.38-2.3)a | 33-2.3 (2.38-2.3) | 33-2.3 (2.38-2.3) | |

| Unique reflections | 21733 | 21681 | 21383 | |

| Redundancy | 1.76 | 1.76 | 1.72 | |

| Completeness (%) | 96.9 (95.6)a | 96.7 (95.3) | 95.4 (95.8) | |

| Average I/σ(I) | 6.7 (2.2)a | 7.0 (2.2) | 7.6 (2.8) | |

| Rmerge (%)b | 7.8 (40.4)a | 7.5 (38.7) | 6.7 (22.6) | |

| f′ | −8.3 | −10.5 | −4.5 | |

| f″ | 4.3 | 4.0 | 0.5 | |

| Mosaicity (°) | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

Numbers in parentheses represent the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = ∑hkl∑i|Ii(hkl)-Iav(hkl)|/∑hkl∑iIi(hkl).

Values correspond to those from the separate chains (A/B or A/B/C) in the asymmetric unit.

MAD Phasing and Refinement—For MAD phasing, crystals were soaked for 1 min in mother liquor containing 1 m NaBr. X-ray data sets at three wavelengths (λremote = 0.92871 Å, λpeak = 0.91979 Å, λedge = 0.919999 Å) were collected on a bromide-soaked mFadA crystal at beam line 4.2.2 at ALS to a resolution of 2.3 Å. Three bromide sites with high occupancies (1.17, 0.98, 0.37) were located with the program SOLVE (12) and used to derive phases with a figure of merit of 0.51. Density modification with the program RESOLVE (13) was used to improve the quality of the electron density map. Automatic chain tracing with the program RESOLVE yielded several helical fragments. Manual tracing in the program O (14) was used to fill in the gaps. The model was refined against a wild-type mFadA data set collected at APS beamline BM-19 to a resolution of 2.0 Å by simulated annealing using the program CNS (15).

For the variants, phases were obtained by molecular replacement using wild-type mFadA as the search model. Unambiguous rotation and translation solutions were obtained using different ranges of intensity data and integration radii with the program PHASER (16). Following rigid body and simulated annealing refinement in the program CNS, the model was manually adjusted in the program O (14) prior to a final round of simulated annealing refinement.

The stereochemical quality of the models was assessed using the program PROCHECK (17). Coordinates and x-ray data for wild-type mFadA and variants L14A (in two different crystal forms) and L76A were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the codes 3ETW, 3ETX, 3ETY, and 3ETZ, respectively.

Structural Similarity Searches—Structural similarity searches were carried out on the DALI server (18).

Dynamic Light Scattering—Dynamic light scattering was used to provide a quantitative assessment of the aggregation behavior of the protein. Measurements were performed at 277 K using a DynaPro instrument (Wyatt Technology Corp., Santa Barbara, CA) on 20-μl samples of mFadA at 2 mg/ml in 10 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, pH 8.0. The dynamic light-scattering data were analyzed with the software provided by the manufacturer to determine the percentage of monodispersity.

FPLC Superdex-200 Size-exclusion Chromatography—Experiments were performed at 277 K in 10 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm NaCl, 0.02% NaN3, pH 8.0. The samples were injected directly into the sample loop of anÄKTA Basic FPLC chromatography system (GE Healthcare) and onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The protein peaks were detected by a UV monitor at a wavelength of 280 nm.

Molecular Graphics—Molecular graphics were produced using the program PyMOL.

Transmission Electron Microscopy—A total of 7.5 μg of FadA protein was mounted on Formvar carbon support nickel grid (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. After the solution was removed, proteins were stained with 50% uranyl acetate at room temperature for 1 min. Unmounted proteins and excess dye were removed, and the specimen grid was dried at room temperature for 16 h. Observation was carried out using a Jeol JEM-1200EX electron transmission microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) with 80 kV of electron acceleration voltage. The images along with the scale bars were enlarged on 8 × 10-inch photo prints. Diameters of the filaments were measured by a ruler and estimated based on the magnification and the scale bar.

Inhibitory Tissue-Cell Attachment Assay—The inhibitory tissue-cell attachment assay was performed as described previously (8). FadA proteins were added to monolayers of Chinese hamster ovary and OKF6/Tert cells followed by the addition of F. nucleatum at a multiplicity of infection of 50-150:1. Following a 1-h incubation at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed with water. The bacterial colonies were counted, and the level of attachment was expressed as the percentage of bacteria recovered following cell lysis relative to the total number of bacteria initially added. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

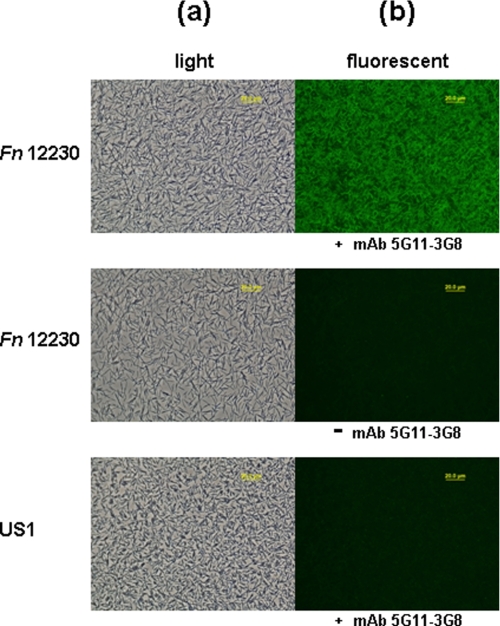

FadA Is Exposed on the Bacterial Cell Surface—Because mFadA easily dissociates from the bacteria (8), it is likely exposed on the bacterial cell surface. To confirm this, immunofluorescent staining of non-permeabilized F. nucleatum using anti-FadA mAb 5G11-3G8 was performed (Fig. 2). Wild-type F. nucleatum 12230 was stained positively by mAb 5G11-3G8 and the FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies but not by the secondary antibody alone. The fadA deletion mutant, US1 (2), was not stained with mAb 5G11-3G8. Thus, the staining of FadA was specific, confirming that FadA is exposed on the surface of F. nucleatum 12230.

FIGURE 2.

Immunofluorescent staining of wild-type F. nucleatum 12230 and the fadA deletion mutant, US1, using anti-FadA mAb 5G11-3G8 as primary antibodies and FITC-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibodies. F. nucleatum 12230 was also incubated directly with the secondary antibodies without prior incubation with mAb 5G11-3G8. The same fields were observed under both light (a) and fluorescence (b) microscope using a ×40 objective.

The Crystal Structure of Wild-type mFadA—The crystal structure of wild-type mFadA was determined to a resolution of 2.3 Å by MAD phasing using crystals soaked for 1 min in mother liquor containing 1 m NaBr. The emerging model was subsequently refined against another wild-type mFadA data set to a resolution of 2.0 Å. All residues are in allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, and the stereochemistry is within acceptable limits of deviation from ideal values (Table 1). The structure was refined with all 15,871 reflections to a resolution of 2.0 Å; the Rcryst and Rfree are 22.5 and 25.4%, respectively. The model consists of residues 4-112 of mFadA, 162 water molecules, and one thiocyanate ion. There is no electron density for the first 3 residues at the N terminus or for residues 113-119 corresponding to the C-terminal hexahistidine tag.

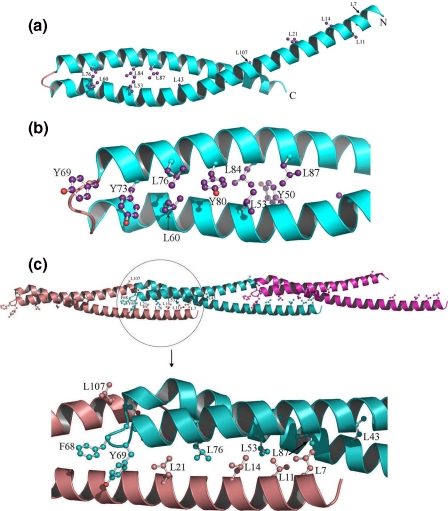

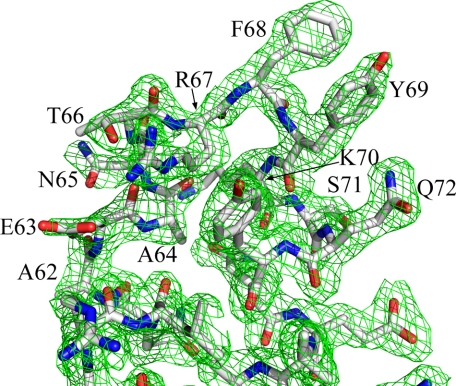

The molecule of mFadA has an elongated helix-loop-helix structure consisting of two antiparallel α-helices connected by an 8-residue loop (Fig. 3a). Fig. 4 shows a 2Fo-Fc electron density map of the loop region in which all depicted residues have been omitted from the phase calculation. The overall dimensions of the molecule are ∼100 × 20 × 20 Å with the N- and C-terminal α-helices being 90 and 70 Å long, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Crystal structure of mFadA. a, ribbon diagram of mFadA. Leucine residues are shown in ball-and-stick representation. b, leucine and tyrosine residues in the vicinity of the hairpin loop. The hydroxyl group of tyrosine is shown in red. c, a trimer of mFadA formed by the interaction of the monomer in the asymmetric unit with neighboring molecules related by a simple translation along the crystallographic b axis. Leucines and residues of the hairpin loop are shown in ball-and-stick representation.

FIGURE 4.

2Fo-Fc electron density map of the hairpin region at 2. 0 Å resolution at contour level of 1.4 standard deviations above the mean. mFadA is shown in stick representation. All labeled residues were omitted from the phase calculation.

The Role of Leucine Residues—Leucine residues play a prominent structural role. There are 11 leucines in the 111-residue mFadA. Some of the leucines are 7 residues apart (Leu7-Leu14-Leu21 and Leu53-Leu60) as in leucine zippers, but others are not. The two antiparallel helices are stabilized by the two interhelical leucine-leucine contacts Leu53-Leu84 and Leu60-Leu76 (Fig. 3b). Additionally, Leu7-Leu11 provide intramolecular contacts between leucine residues on the same arm of the helical bundle (Fig. 3c). A string of three tyrosine residues (Tyr50, Tyr73, and Tyr80) is interspersed between leucine residues on the helix interface (Fig. 3b). The aromatic rings of these tyrosine residues are buried to provide hydrophobic contacts with leucine and other apolar side chain atoms, whereas the hydroxyl groups are exposed to solvent (supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

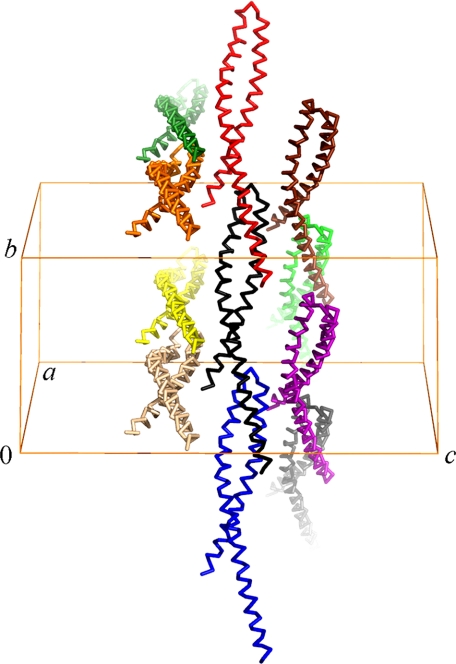

The crystal structure of mFadA also reveals intermolecular contacts, the overwhelming majority of which are with molecules related by a simple translation along the b axis, roughly parallel to the axis of the antiparallel helix bundle (Fig. 3c). Leucine residues again play an important role in the non-covalent intermolecular interactions. Residues Leu7, Leu11, Leu14, and Leu21 on the N-terminal helix interact with Leu53, Leu76, and Leu84 from the central part of the neighboring molecule along the b axis. Additional intermolecular contacts are provided by Leu14, Leu21, Leu60, and Leu76, interacting respectively with Tyr80, Tyr73, and Tyr18 of the neighboring molecule related by the same translation along the crystallographic b axis (supplemental Table 2). Intermolecular salt bridges exist between Glu10, Asp15, Glu17, Glu25, Arg33, Arg56, Arg67, Glu75, Lys79, and Arg86 with oppositely charged amino acid residues on neighboring molecules (supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, the assembly of mFadA molecules in the crystal lattice represents a model for the long antenna-like structures.

Mutagenesis of FadA—To examine the roles of the leucine residues, FadA variants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the pYWH417-6 plasmid as template, which carried the entire fadA gene. Leucine variants L14A, L14G, L14E, L14V, L21E, and L76A were generated. All mutational changes were verified by DNA sequencing analysis.

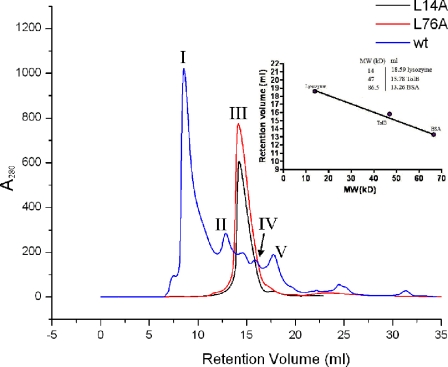

Oligomerization of FadA and Its Variants—Dynamic light scattering of wild-type mFadA yielded a relatively low monodispersity value of 0.18, similar to the value of 0.15 measured for lysozyme as a standard. This result indicates that mFadA does not aggregate in a nonspecific manner. Indeed, wild-type mFadA forms distinct oligomers in solution, as evidenced by peaks I-V from size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 5). Reapplication of the material corresponding to peak I resulted in similar distribution of different oligomeric species, suggesting an equilibrium between different oligomerization states (data not shown). In contrast, mFadA containing L14A or L76A exhibited a drastically lower degree of oligomerization, corresponding to peak III (Fig. 5), as did L14V, L14G, L14E, and L21E (data not shown). It is not possible to deduce accurate molecular weight values from this elution profile because FadA is an elongated molecule, whereas the calibration curve displayed in Fig. 5, inset, was generated with globular proteins. An elongated protein is expected to migrate faster in a size exclusion column than a globular protein of the same molecular weight. Consequently, the true molecular weight of FadA oligomers might be lower than the value obtained by interpolation of the calibration curve. All three variants elute corresponding to an apparent molecular mass of about 50 kDa, which corresponds to an apparent oligomerization state containing 3.7 monomers. Thus, one may conclude that the L14A and L76A proteins form oligomers no larger than trimers or tetramers.

FIGURE 5.

FPLC Superdex S-200 size exclusion chromatography of wild-type and variant mFadA. A280 represents the absorbance at 280 nm in arbitrary units. Wild-type (wt) mFadA eluted as five major peaks I, II, III, IV, and V, possibly corresponding to polymer, tetramer, trimer, dimer, and monomer, respectively. The L14A and L76A variant mFadA did not form aggregates higher than tetramer. Inset, molecular weight (MW) calibration curve with the proteins lysozyme, TolB, and bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Crystal Structure of Variant mFadA—The FadA variants crystallized differently from the wild-type protein (Table 1). Although they all crystallized in the same hexagonal space group P61 as wild-type mFadA, the length of the c axis is markedly different in the various crystal forms. L14A also crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21.

The variant structures were essentially identical to wild-type mFadA with r.m.s. deviations for corresponding Cα atoms ranging from 0.6 to 1.1 Å, except that in L14A and L76A, the alanine residues at positions 14 and 76 lacked some of the inter- and intramolecular contacts of the leucine residues in the wild-type structure.

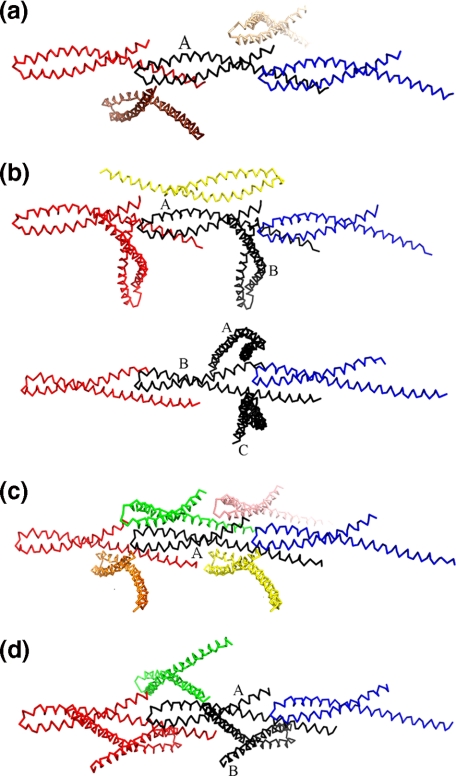

Some packing interactions with neighboring molecules in the variant FadA crystal structures are different from wild type and from each other (Fig. 6). However, the head-to-tail interaction between neighboring molecules observed in the wild-type crystal structure (Fig. 7) is conserved in all the variant structures, suggesting that the head-to-tail interaction represents a physiologically relevant oligomerization motif.

FIGURE 6.

Variation of interfaces in wild-type and variant proteins. Molecules are shown as Cα traces. The central molecule is shown in black. a, the central molecule of wild-type mFadA and four neighboring molecules. b, L14A form I, with molecule A (top) and molecule B (bottom) in the asymmetric unit. c, L14A form II. d, L76A. The head-to-tail interactions are conserved in all the structures, whereas other intermolecular interactions vary.

FIGURE 7.

Packing diagram of the wild-type mFadA crystal structure. Individual protomers are shown in α-carbon representation in different colors. The unit cell axes a, b, and c are indicated. Note that the helical axes are roughly parallel to the crystallographic b axis.

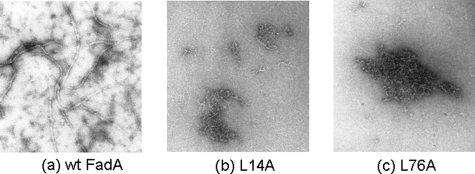

Filament Formation of FadA and Its Variants—Electron microscopy studies revealed formation of long filaments by purified wild-type FadA (Fig. 8). The filaments varied in width, ranging from 30 to 170 Å, as well as in length. L14A and L76A exhibited no filaments (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Electron micrographs of FadA. a, wild type; b, L14A; and c, L76A. Magnification: ×50,000. wt, wild type.

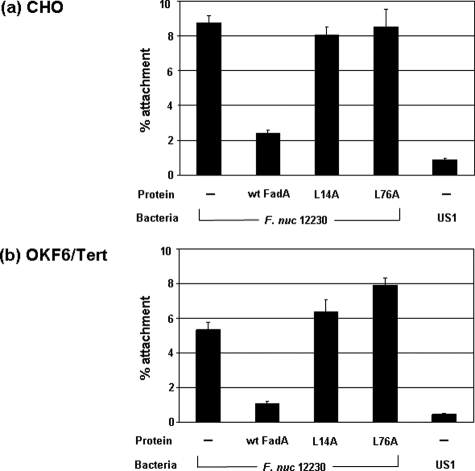

Binding of FadA to the Host Cells—Purified FadA and its variants were tested in the inhibitory attachment assay. Wild-type FadA inhibited F. nucleatum binding to both Chinese hamster ovarian cells and immortalized oral keratinocytes OKF6/Tert cells, but the L14A and L76A variants did not (Fig. 9). These results indicate that only the wild-type FadA had functional binding activity, which was lost in the variants.

FIGURE 9.

Inhibition of attachment of F. nucleatum 12230 (F. nuc 12230) to Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)(a) and OKF6/Tert (b) cells by wild-type FadA (wt FadA) and its variants. F. nucleatum 12230 was added to the monolayers either directly or following preincubation of wild-type FadA (50 μg/well), L14A, or L76A variants (each at 200 μg/well). F. nucleatum 12230 US1 was added directly to the host cells as a negative control.

DISCUSSION

We have shown previously that FadA is a novel adhesin and invasin from F. nucleatum involved in interactions with host cells (8). In this study, we demonstrate that FadA is likely exposed on the bacterial surface. Furthermore, a detailed structural analysis of mFadA was performed.

The crystal structure of mFadA reveals a quintessential role for leucine residues, which mediate both intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. First, they comprise the main “molecular glue” to associate the two helical arms of the monomer; second, they form the head-to-tail association of monomers to form the antenna-like polymers. The unique interactions mediated by leucine residues lead to formation of a novel structural motif termed “leucine chain.” This chain is formed by intermolecular hydrophobic interactions between Leu7, Leu11, Leu14, and Leu21 on the N-terminal arm of one monomer with Leu53, Leu76, and Leu84 from the neighboring monomer. In addition, intramolecular Leu53-Leu84 and Leu60-Leu76 interactions play an important role in stabilizing the hairpin structure of the monomers. Mutagenesis of these leucine residues resulted in severely diminished oligomerization, abrogation of filament formation, and failure of binding to host cells.

It should be pointed out that although the His tag was present in both wild-type and mutant FadA constructs, it is disordered in all but one crystal structure (one of the two molecules in the asymmetric unit of variant L76A where it forms a crystal contact with a tyrosine residue from a neighboring molecule). Therefore, the His tag cannot be involved in any physiologically relevant contact, nor does it play any role in the oligomerization of FadA.

Although the FadA structure bears some resemblance to a leucine zipper, there are major differences between these two motifs. The leucine zipper is a dimerization motif between parallel α-helices involving a heptad repeat of leucine residues (19). In the FadA structure, some leucine residues are 7 residues apart, but others are not. Furthermore, although the intermolecular leucine-leucine interactions are between parallel α-helices, the intramolecular interactions are between antiparallel helices. Although Leu53, Leu60, Leu76, Leu84, and Leu87 are involved in intramolecular interactions between the two antiparallel α-helices, the N-terminal leucine residues Leu7, Leu11, Leu14, and Leu21 form intermolecular contacts with Leu53, Leu76, and Leu87 of a neighboring molecule in a parallel fashion. Note that Leu53, Leu76, and Leu87 are involved in both intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. Thus, the leucine chain represents a novel α-helical oligomerization motif between the N-terminal region of one subunit and the C-terminal region of another subunit.

Based on the current observations as well as on previous studies, we propose a filamentous model of FadA in which mFadA monomers are linked in a head-to-tail pattern. The filament emanates from the outer membrane to allow binding to its receptor. Such a filamentous model is supported by the crystal structures of wild-type and variant mFadA. Furthermore, it is supported by observations from electron microscopy. The head-to-tail pattern has recently been observed in the crystal structure of the major pilin subunit from Streptococcus pyogenes, albeit utilizing a different oligomerization motif (1).

The observation that the L14A and L76A variant FadA proteins are deficient in filament formation and binding to host cells is an indication that each of these 2 leucine residues is crucial for biological function. However, in the crystal structure of these two variant proteins, the intermolecular head-to-tail interactions are preserved, albeit weakened by the lack of one leucine contact. The lower degree of oligomerization of these variant proteins observed in solution might be a consequence of the weakened head-to-tail interaction. However, the abrogation of biological function in the absence of Leu14 or Leu76 points to an additional role of these leucine residues in filament formation beyond the head-to-tail interactions. It is conceivable that the filaments seen in the electron micrographs represent a higher order structure of FadA formed by intertwining or bundling of FadA chains. Such an explanation is supported by the observation that these filaments range in width up to 170 Å, about 5-6 times the width of a single mFadA leucine chain. It may well be that both Leu14 and Leu76 are critical to the formation of the higher order structures, and mutation of these leucine residues may thus prevent filament formation. The lack of inhibition of attachment of F. nucleatum to host cells by L14A and L76A may be explained by their inability to form higher order filaments.

The receptor-binding site of FadA has yet to be identified. Based on the model and the structural features of FadA, we speculate that the hairpin loop region may be the receptor-binding site because it is a unique and outstanding feature in this otherwise all-helical structure. Support of this hypothesis comes from the fact that FadA shares similarity with other coiled-coil helical structures with r.m.s. deviations of corresponding Cα atoms ranging from 2 to 3 Å. One example is the receptor-binding domain of the bacterial toxin colicin E3 with an r.m.s. deviation of 2.6 Å for 105 corresponding Cα atoms (20). The receptor-binding site on colicin E3 is located on the hairpin loop connecting the two coiled-coil helices (21). Because the hairpin of the last monomer at the tip of the antenna would be completely exposed, it is plausible that this exposed hairpin is the attachment site to the host cells. It is possible that multiple hairpin loops at the tip of the filament have to be juxtaposed for binding to the receptor, supporting the notion of possible involvement of higher order filaments in function. The role of the loop region in FadA structure and function is currently under investigation.

Also unclear at this stage is the role of pre-FadA in FadA structure and function. Is it possible that pre-FadA provides an anchor in the inner membrane and serves as a base for the mFadA monomers to build into a filamentous structure? If so, how does the FadA filament penetrate the outer membrane? Are there accessory proteins involved? These questions are also under investigation.

In summary, FadA likely functions as a filament, in which elongated monomers are linked together in a head-to-tail fashion via the novel leucine chain motif. Further investigation of the FadA structure and function will advance our understanding of the colonization mechanism of this opportunistic pathogen in the host and help identify therapeutic targets for prevention and treatment of infections associated with this organism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Molecular Biology Collaborative Access Team (MB-CAT) at beam line 4.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source, Berkeley, CA and the staff of beam line BM-19 of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne, IL for expert assistance in x-ray data collection, Jonathan Ross and Hongqi Liu for technical assistance in mutagenesis of FadA, and Hisashi Fujioka for performing the electron microscopy studies.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3ETW, 3ETX, 3ETY, and 3ETZ) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1DE14924, KO2DE16102, and R21DE17165 (to Y. W. H.). This work was also supported by a grant from the Philip Morris External Research Program (to Y. W. H.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains three supplemental tables and a supplemental figure.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: mFadA, mature FadA; ALS, Advanced Light Source; APS, Advanced Photon Source; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; FPLC, fast protein liquid chromatography; mAb, monoclonal antibodies; MAD, multiple wavelengths anomalous dispersion; r.m.s., root mean square.

References

- 1.Kang, H. J., Coulibaly, F., Clow, F., Proft, T., and Baker, E. N. (2007) Science 318 1625-1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han, Y. W., Ikegami, A., Rajanna, C., Kawsar, H. I., Zhou, Y., Li, M., Sojar, H. T., Genco, R. J., Kuramitsu, H. K., and Deng, C. X. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187 5330-5340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore, W. E., and Moore, L. V. (1994) Periodontol. 2000 5 66-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaim, W., and Mazor, M. (1992) Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 251 9-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han, Y. W., Redline, R. W., Li, M., Yin, L., Hill, G. B., and McCormick, T. S. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72 2272-2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, H., Redline, R. W., and Han, Y. W. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 2501-2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han, Y. W., Shi, W., Huang, G. T. J., Kinder Haake, S., Park, N.-H., Kuramitsu, H., and Genco, R. J. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68 3140-3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu, M., Yamada, M., Li, M., Liu, H., Chen, S. G., and Han, Y. W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 25000-25009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nithianantham, S., Xu, M., Wu, N., Han, Y. W., and Shoham, M. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Crystalliz. Comm. 62 1215-1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pflugrath, J. W. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 1718-1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terwilliger, T. C., and Berendzen, J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 849-861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terwilliger, T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56 965-972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W., and Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 47 110-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T., and Warren, G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 905-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Read, R. J. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57 1373-1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283-291 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm, L., and Sander, C. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26 316-319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landschulz, W. H., Johnson, P. F., and McKnight, S. L. (1988) Science 240 1759-1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soelaiman, S., Jakes, K., Wu, N., Li, C., and Shoham, M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8 1053-1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurisu, G., Zakharov, S. D., Zhalnina, M. V., Bano, S., Eroukova, V. Y., Rokitskaya, T. I., Antonenko, Y. N., Wiener, M. C., and Cramer, W. A. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10 948-954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.