Abstract

Small-conductance (KCa2.1-2.3) and intermediate-conductance (KCa3.1) calcium-activated K+ channels are critically involved in modulating calcium-signaling cascades and membrane potential in both excitable and nonexcitable cells. Activators of these channels constitute useful pharmacological tools and potential new drugs for the treatment of ataxia, epilepsy, and hypertension. Here, we used the neuroprotectant riluzole as a template for the design of KCa2/3 channel activators that are potent enough for in vivo studies. Of a library of 41 benzothiazoles, we identified 2 compounds, anthra[2,1-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-20) and naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-31), which are 10 to 20 times more potent than riluzole and activate KCa2.1 with EC50 values of 430 nM and 2.9 μM, KCa2.2 with an EC50 value of 1.9 μM, KCa2.3 with EC50 values of 1.2 and 2.9 μM, and KCa3.1 with EC50 values of 115 and 260 nM. Likewise, SKA-20 and SKA-31 activated native KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels in murine endothelial cells, and the more “drug-like” SKA-31 (half-life of 12 h) potentiated endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated dilations of carotid arteries from KCa3.1(+/+) mice but not from KCa3.1(-/-) mice. Administration of 10 and 30 mg/kg SKA-31 lowered mean arterial blood pressure by 4 and 6 mm Hg in normotensive mice and by 12 mm Hg in angiotensin-II-induced hypertension. These effects were absent in KCa3.1-deficient mice. In conclusion, with SKA-31, we have designed a new pharmacological tool to define the functional role of the KCa2/3 channel activation in vivo. The blood pressure-lowering effect of SKA-31 suggests KCa3.1 channel activation as a new therapeutic principle for the treatment of hypertension.

The three small-conductance calcium-activated K+ channels KCa2.1 (SK1), KCa2.2 (SK2), and KCa2.3 (SK3) and the intermediate-conductance KCa3.1 channel (IK1, SK4) play important roles in various physiological functions by modulating calcium-signaling cascades and regulating membrane potential. All four channels are voltage-independent and open in response to calcium binding to calmodulin, which serves as the calcium-sensing β-subunit of these channels (Xia et al., 1998; Fanger et al., 1999). KCa2 channels are widely expressed throughout the nervous system and are probably best known for underlying the apamin-sensitive medium after hyperpolarization and for modulating neuronal firing frequency and neurotransmitter release (Stocker, 2004; Wulff et al., 2007). Outside of the nervous system, KCa2 channels, especially KCa2.3, are involved in blood pressure regulation (Taylor et al., 2003), contractility of urinary bladder smooth muscle, and metabolism (Wulff et al., 2007). In contrast, KCa3.1 channels play important roles in cellular proliferation, secretion, and volume regulation and are expressed in erythrocytes, T- and B-cells, microglia and macrophages, secretory epithelia, proliferating fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells (Wulff et al., 2007). Like KCa2.3, KCa3.1 is further expressed in vascular endothelium and contributes to blood pressure control by initiating the so-called endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) response, a nitric oxide- and prostacyclin-independent component of endothelium-dependent relaxation (Edwards et al., 1998; Eichler et al., 2003; Fleming, 2006; Si et al., 2006; Köhler and Hoyer, 2007).

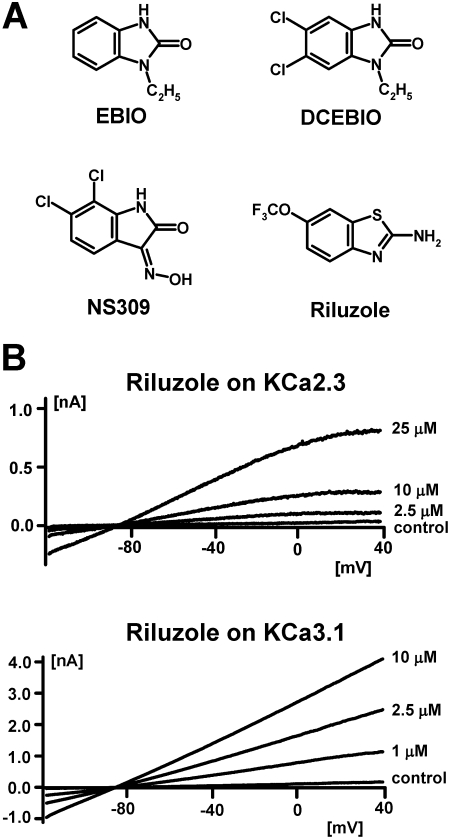

Pharmacologically, KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels can be easily distinguished by their different sensitivity to peptide and small-molecule inhibitors. KCa2 channels are blocked by the 18-amino acid bee venom toxin apamin, the larger scorpion toxins scyllatoxin and tamapin, and the permanently charged bisquaternary molecules d-tubocurarine, dequalinium, UCL1684, and UCL1848 (Stocker et al., 2004; Wulff et al., 2007). In contrast, KCa3.1 channels are inhibited by the scorpion toxins maurotoxin and charybdotoxin and the triarylmethanes clotrimazole, TRAM-34, and ICA-17043 (Wulff et al., 2007). Although none of these inhibitors cross-reacts to the other channel type, both KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels are activated with very similar potencies by relatively simple benzimidazolones and benzothiazoles (Fig. 1A). Ethylbenzimidazolone (EBIO) was first reported to activate intermediate-conductance K+ currents in T84 cells by Devor et al. (1996) and later was confirmed to activate cloned KCa3.1 channels with an EC50 value of 30 μM and cloned KCa2 channels with EC50 values of 300 to 450 μM (Wulff et al., 2007). To increase the potency of EBIO, Singh et al. (2001) performed a structure activity study with 30 benzimidazolone derivatives and identified 5,6-dichloro-EBIO, a compound that activates KCa3.1 with an EC50 value of 750 nM (Singh et al., 2001) and KCa2.2 with an EC50 value of 27 μM (Pedarzani et al., 2001). The structurally related oxime NS309 is significantly more potent and activates KCa2 and KCa3.1 channels at submicromolar concentrations (Strøbæk et al., 2004) but unfortunately has an extremely short half-life, which precludes its in vivo use.

Fig. 1.

A, chemical structures of EBIO, 5,6-dichloro-EBIO, NS309, and riluzole. B, effect of increasing concentrations of riluzole on KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 currents elicited with 250 nM concentration of free Ca2+ from COS-7 cells transiently transfected with hKCa2.3 or hKCa3.1.

To obtain a KCa2/3 channel activator that is potent enough to probe the therapeutic potential of KCa2/3 channel activation in vivo, we here used the neuroprotectant riluzole, which shows some structural similarity to EBIO, as a template for the design of a more potent KCa2/3 channel activator. Riluzole was originally developed in the 1950s (Domino et al., 1952) as a central muscle relaxant and later was studied extensively as an anticonvulsant and neuroprotective agent. Today, riluzole is registered under the trade name Rilutek for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Riluzole exhibits various pharmacological activities, the most prominent of which are inhibition of neuronal Na+ channels at concentrations of 1-50 μM (Debono et al., 1993; Song et al., 1997; Zona et al., 1998; Duprat et al., 2000) and activation of KCa2/3 channels with EC50 values of 10 to 20 μM (Grunnet et al., 2001; Cao et al., 2002). Riluzole has further been reported to inhibit delayed-rectifier K+ channels and to activate two-pore K+ channels at 30 to 100 μM (Debono et al., 1993; Song et al., 1997; Zona et al., 1998; Duprat et al., 2000). After screening a “smart” library of 55 carefully selected riluzole derivatives, we identified SKA-31, which activates the cloned human KCa3.1 and native KCa3.1 channels in murine endothelium (Si et al., 2006) with an EC50 value of 250 nM and KCa2.1 to KCa2.3 channels with EC50 values in the low micromolar range. In addition to a 10-fold increase in potency in comparison to riluzole, SKA-31 also exhibits a greater selectivity over other ion channels. Taken together with excellent pharmacokinetic properties such as low protein binding and a long half-life, these improved characteristics make SKA-31 an excellent pharmacological tool compound to probe the function and therapeutic potential of KCa2 and KCa3 channel activation in vivo. In keeping with the role of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 in mediating endothelial hyperpolarization and thus contributing to endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation (Edwards et al., 1998; Eichler et al., 2003; Si et al., 2006; Köhler and Hoyer, 2007), SKA-31 potentiated EDHF-type dilations in murine carotid arteries and lowered arterial blood pressure in both normotensive and hypertensive mice in a KCa3.1-dependent fashion. Based on SKA-31's blood pressure-lowering effect, we suggest that KCa3.1 channel activation might constitute a new therapeutic target for the treatment of hypertension.

Materials and Methods

Commercially Available Benzothiazoles. Riluzole (1, CAS 1744-22-5) and NS8593 (N-[(1R)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthalenyl]-1H-benzimidazol-2-amine hydrochloride (CAS 875755-24-1) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Compounds 2 (SKA-12, CAS 132877-27-1) and 5 (SKA-46, CAS 97963-59-2) were from Chemgenx LLC (Princeton, NJ). Compounds 3 (SKA-5, CAS 55690-60-3) and 10 (SKA-4, CAS 6285-57-0) were from Alfa Aesar (Pelham, NH). Compounds 6 (SKA-47, CAS 97963-62-7), 11 (SKA-16, CAS 17557-67-4), 14 (SKA-17, CAS 6294-52-6), 19 (SKA-48, CAS 29927-08-0), and 20 (SKA-18, CAS 348-40-3) were purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Compounds 4 (SKA-6, CAS 4845-58-3), 8 (SKA-1, CAS 136-95-8), and 22 (SKA-3, CAS 95-24-6) were purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Compounds 7 (SKA-41, CAS 436151-95-0) and 25 (SKA-51, CAS 777-12-8) were from Oakwood Products Inc. (West Columbia, SC). Compounds 15 (SKA-13, CAS 74821-70-8) and 27 (SKA-19, CAS 326-45-4) were from Matrix Scientific (Columbia, SC). Compounds 17 (SKA-32, CAS 65948-19-8) and 33 (SKA-45, CAS 1203-55-0) were from Scientific Exchange Inc. (Center Ossipee, NH). Compounds 21 (SKA-42, CAS 352214-93-8) and 26 (SKA-34, CAS 60388-38-7) were from Syntech Development (Franklin Park, NJ). Compound 28 (SKA-11, CAS 447448-64-8) was from ChemDiv, Inc. library (San Diego, CA). Compound 31 (SKA-44, CAS 143174-11-2) was from Salor Catalog, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Compound 41 (SKA-30, CAS 313223-82-4) was from Chembridge Corporation (San Diego, CA).

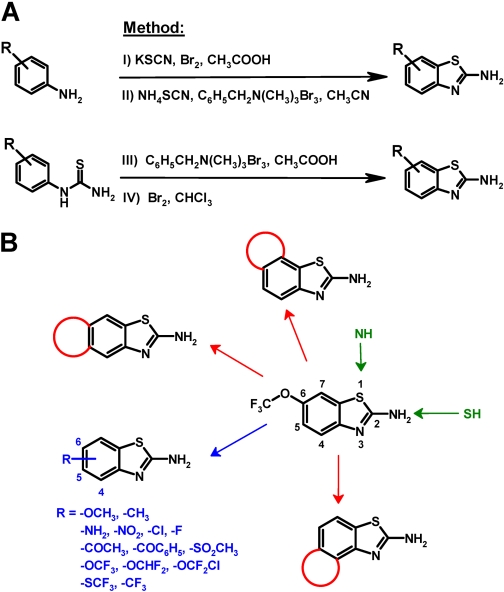

Chemical Synthesis of Benzothiazoles. Benzothiazoles that were not commercially available were synthesized in our laboratory either from appropriately substituted amines and potassium or ammonium thiocyanate or from appropriately substituted thioureas in a Hugerschoff reaction in the presence of molecular bromine (Fig. 2A). In many cases, we used benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (Jordan et al., 2003) or tetrabutyl ammonium tribromide to deliver bromine in stoichiometric amounts as an alternative to liquid bromine to avoid unwanted ring bromination of activated aromatic systems. Compounds reported previously were characterized by melting point and 1H NMR to confirm their chemical identity (data not shown, available on request). New chemical entities (NCEs) were additionally characterized by 13C NMR, mass spectrometry, and combustion analysis.

Fig. 2.

A, 2-aminobenzothiazoles were synthesized from differently substituted amines and potassium (I) or ammonium thiocyanate (II) (Kaufman, 1928; Jimonet et al., 199) or through oxidative cyclization of appropriately substituted thioureas (III) in a Hugerschoff reaction (Jordan et al., 2003) in the presence of liquid bromine (IV). The letters I, II, III, and IV correspond to general methods I, II, III, and IV described under Materials and Methods. Because liquid bromine is difficult to manipulate on a small scale and an excess of bromine can result in bromination of the benzene ring (Jordan et al., 2003), we often used crystalline organic ammonium tribromides such as benzyltrimethylammonium tribromide or tetrabutylammonium tribromide (III). These tribromides deliver molecular bromine in stoichiometric amounts and thus avoid the unwanted ring bromination of activated substrates (Kajigaeshi et al., 1987, 1988). B, overall synthetic strategy.

General Method I. Differently substituted aromatic amines and potassium thiocyanate (molar ratio, 1:4) were dissolved in glacial acetic acid at RT. Liquid bromine (1.2-1.5 equivalent) in glacial acetic acid was then added drop-wise, maintaining the reaction temperature below 30°C. After the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was stirred, and the progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After completion of the reaction as indicated by the disappearance of starting material on TLC analysis, the solids were filtered off and then washed first with glacial acetic acid and then with water. The filtrate was diluted with 300 ml of water, neutralized to pH 7 to 7.5, and then cooled overnight in the refrigerator to allow the product to precipitate. The product was filtered, washed with cold water, and dried under vacuum. The dried residue was decolorized with charcoal and recrystallized.

General Method II. Equimolar amounts of the substituted aromatic amine and ammonium thiocyanate were dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile at RT. Benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (1.1-1.2 equivalent) was added to the solution, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT. After completion of the reaction as determined by TLC, the reaction mixture was concentrated to dryness under vacuum, and the residue was diluted with 100 ml of water. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 to 7.5 with aqueous 10% potassium carbonate. The slurry was cooled on ice and then filtered. The solids were washed with water and dried under suction. The residue was decolorized with charcoal and recrystallized.

General Method III. Differently substituted thioureas were dissolved in glacial acetic acid at RT. An equimolar amount of benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide was added to the solution, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT. After completion of the reaction as determined by TLC, the reaction mixture was diluted with 300 ml of ice-cold water. The unreacted thiourea was filtered off and washed with water. The filtrate was cooled to 5°C and adjusted to pH 7 to 8. The slurry was kept in the fridge for 24 h, filtered, washed with water, and the residue was dried under suction. The dry residue was decolorized with charcoal and recrystallized.

General Method IV. Differently substituted thioureas were dissolved in anhydrous chloroform at RT. Liquid bromine dissolved in chloroform was added drop-wise maintaining the reaction temperature below 30°C. After complete addition of bromine, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 4 h and the liquid decanted. The residual solid was heated to 100°C for 2 h to complete the reaction. The crude solid was then cooled, suspended in water, and made alkaline, pH 10 to 12, under ice-cold conditions with 30% aqueous sodium hydroxide. The resulting slurry was then filtered, and the filtered-off solids (a mixture of thiourea and the benzothiazol-2-amine) were washed with water to neutral pH and dried under suction. The solids were resuspended in dilute hydrochloric acid for 30 to 45 min to dissolve the product amine as a hydrochloride. The unreacted thiourea was filtered off, and the filtrate was neutralized with 10% potassium carbonate, pH 8 to 10, under ice-cold conditions. The precipitated free base was filtered, washed with water, dried under vacuum, decolorized with charcoal, and recrystallized.

Compound 9 (SKA-36) was prepared by reduction of SKA-4 (5.0 g, 25.6 mmol) with a mixture of zinc (6.5 g, 99.4 mmol), anhydrous zinc chloride (6.5 g, 47.7 mmol), and concentrated hydrochloric acid (70 ml) in ethanol (150 ml) as medium at 25 to 27°C. The product was isolated as a green solid (510 mg, 12%); m.p. = 204.3°C (CAS 5407-51-2).

Compound 12 (SKA-24) was prepared from 4-aminoacetophenone (2.0 g, 14.8 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (3.9 g, 52.0 mmol), and liquid bromine (2.6 g, 16.3 mmol) according to general method I. The final product was isolated as a yellow solid (2.7 g, 95%); m.p. = 248.1°C (CAS 21222-61-7).

Compound 13 (SKA-2) was prepared from p-anisidine (2.5 g, 20.3 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (7.8 g, 80.3 mmol), and liquid bromine (3.7 g, 23.4 mmol) according to general method I. The product was recrystallized from methanol as an off-white solid (1.9 g, 58%); m.p. = 166.4°C (CAS 1747-60-0).

Compound 16 (SKA-7) was prepared from 4-benzylaniline (1.0 g, 5.5 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (2.1 g, 21.8 mmol), and liquid bromine (1.2 g, 7.4 mmol) according to general method I. The final product was recrystallized from ethanol-petroleum ether mixture (70:30) as a pale yellow solid (1.3 g, 94%); m.p. = 174.1°C (CAS 129121-46-6).

Compound 18 (SKA-22) was prepared from 4-aminobenzophenone (2 g, 10.14 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (3.94 g, 40.56 mmol), and liquid bromine (1.8 g, 11.2 mmol) according to general method I. The final product was isolated as a yellow solid (2.5 g, 96%); m.p. = 247.1°C (CAS 16586-50-8).

Compound 23 (SKA-8) was prepared from 3-(trifluoromethoxy)-aniline (500 mg, 2.8 mmol), ammonium thiocyanate (217 mg, 2.8 mmol), and benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (1.1 g, 2.9 mmol) according to general method II. The product was isolated as the free base as a creamy white solid (400 mg, 61%); m.p. = 80.9°C; literature as hydrochloride: 158°C (CAS 752969-85-0). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 7.4 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.44 Hz, 6-H), 6.7 (s, 1H, 4-H), 6.6 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.67, 7-H), 6.2 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2).

Compound 24 (SKA-35) was prepared from 2-(trifluoro-methoxy)aniline (250 mg, 1.4 mmol), ammonium thiocyanate (109 mg, 1.5 mmol), and benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (568 mg, 1.5 mmol) according to general method B. The product was isolated as a free base, an off-white solid (94 mg, 28%); m.p. = 71.9°C (CAS 235101-36-7).

Compound 29 (SKA-53) was prepared by dissolving 2-(2-aminophenyl) benzo-thiazole (500 mg, 2.2 mmol) and ammonium thiocyanate (168.1 mg, 2.2 mmol) in 65 ml of anhydrous acetonitrile at RT. Benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (880.5 mg, 2.3 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 36 to 40 h at RT. The crude product was isolated according to general method II. The crude product was dissolved in 30 ml of acetone, decolorized with charcoal, and recrystallized from a mixture of 20% ethyl acetate in benzene. The isolated solid was then refluxed in petroleum ether, filtered, washed with petroleum ether, and dried to obtain a yellow solid (139 mg, 23%); m.p. = 175.8°C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 8.15 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.30 Hz, 4′-H), 8.07 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.39 Hz, 5-H), 7.93 (m, 1H, 6-H), 7.89 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 7.56 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.17 Hz, 5′-H), 7.51 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.92 Hz, 7′-H), 7.48 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.33 Hz, 6′-H), 7.04 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.13 Hz, 7-H); MS (70 eV) m/z: 283 (97%, M+), 257 (9.5%), 250 (29.5%, [C14H9N3S]+), 224 (9%), 142 (6.5%, [C8H5N3]+), 108 (6.3%, [C6H3S]+); calculated for C14H9N3S2 (283.38): C, 59.34%; H, 3.20%; N, 14.83%; S, 22.63%; found: C, 59.13%; H, 3.18%, N, 14.77%; S, 22.51%.

Compound 30 (SKA-29) was prepared from 6-aminoindan (2 g, 15.0 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (5.84 g, 60.1 mmol), and liquid bromine (2.7 g, 16.5 mmol) according to general method I. The product was isolated as a yellow solid (1.5 mg, 52%); m.p. = 209.6°C (CAS 83777-91-7).

Compound 32 (SKA-49) was prepared from 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-naphthalen-1-ylamine (500 mg, 3.4 mmol), ammonium thiocyanate (260 mg, 3.4 mmol) and benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (1.4 mg, 3.5 mmol) according to general method II. The isolated free base was recrystallized from a petroleum ether-benzene (70:30) mixture to yield a creamy white solid (184 mg, 27%); m.p. = 125.7°C (CAS No.139331-69-4).

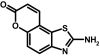

To prepare compound 34 (SKA-31), naphthalen-1-yl-thiourea (2.0 g, 9.9 mmol) was stirred in 50 ml of glacial acetic acid at RT. Benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (3.9 g, 9.9 mmol) was added at RT, and the reaction mixture was then stirred for 48 h. The crude product was isolated according to general method III as a pinkish white solid. The product was further decolorized with charcoal and recrystallized from ethanol as a light pink-colored solid (1.2 g, 61%); m.p. = 178.1°C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 8.40 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.17 Hz, 9-H), 7.91 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.56 Hz, 6-H), 7.80 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.34 Hz, 4-H), 7.65 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 7.56 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.41 Hz, 5-H), 7.52 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.05 Hz, 8-H), 7.46 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.15 Hz, 7-H); MS (70 eV) m/z: 200 (99%, [C11H8N2S]+), 172 (22%, C10H6NS), 140 (10.5%, C10H6N), 114 (7.5%, C9H6); molecular weight calculated for C11H8N2S, 200.0408; found by high-resolution mass spectrometry, 200.0410.

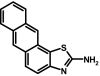

To prepare compound 35 (SKA-20), 2-aminoanthracene (500 mg, 2.6 mmol) and ammonium thiocyanate (198 mg, 2.6 mmol) were dissolved in 50 ml of anhydrous acetonitrile at RT. Benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (1.0 g, 2.7 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 48 h at RT. The crude product was isolated according to general method II and then washed with petroleum ether to remove the unreacted amine. The crude solids were dissolved in acetone under reflux, decolorized with charcoal, and recrystallized from a benzene/petroleum ether mixture (30:70) as a greenish brown solid (167.6 mg, 26%); m.p. = 186.6°C, decomposing. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 8.6 (s, 1H, 11-H), 8.4 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.79 Hz, 4-H), 8.1 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.32 Hz, 10-H), 7.9 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.58 Hz, 7-H), 7.7 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.66 Hz, 9-H), 7.4 (t, 1H, 3J = 7.34 Hz, 8-H), 7.4 (s, 1H, 6-H), 7.1 (dd, 1H, 3J = 8.96 Hz, 4J = 1.94 Hz, 5-H), 6.3 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2); MS (70 eV) m/z: 250 (98.5%, [C15H10N2S]+), 218 (42%, [C15H10N2]+), 190 (14.5%, [C14H8N]+); molecular weight calculated for C15H10N2S, 250.05647; found by high-resolution mass spectrometry, 250.0564.

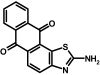

To prepare compound 36 (SKA-21), 2-aminoanthraquinone (500 mg, 2.2 mmol) and ammonium thiocyanate (172 mg, 2.3 mmol) were dissolved in 50 ml of anhydrous acetonitrile at RT. Benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (901 mg, 2.3 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 46 h. The product was isolated according to general method II. The crude product was refluxed in a methanol-acetone mixture (50:50) and filtered hot. It was then further purified by flash chromatography with gradient elution using a petroleum ether and ethyl acetate mixture (75.5 mg, 6%); m.p. = >350°C); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 8.27 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 8.22 (d, 2H, 3J = 5.09 Hz, 7-H, 10-H), 8.12 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.19 Hz, 5-H), 7.92 (m, 2H, 8-H, 9-H), 7.73 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.54 Hz, 4-H); molecular weight calculated for C15H8N2O2S, 280.03066; found by high-resolution mass spectrometry, 280.0306.

Compound 37 (SKA-26) was prepared from 6-aminocoumarin (2 g, 10.2 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (3.9 g, 40.5 mmol), and liquid bromine (1.8 g, 11.1 mmol) according to general method I. The product was isolated as a yellow solid (35 mg, 1.6%); m.p. = 252.7°C (CAS 79492-10-7).

Compound 38 (SKA-50) was prepared from phenylene-1,4-dithiourea (2.0 g, 8.8 mmol) and liquid bromine (2.8 g, 17.7 mmol) according to general method IV. The product was isolated as an off-white solid (518 mg, 26%); m.p. =>350°C) (CAS 16162-28-0); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 7.6 (s, 1H, 4-H), 7.37 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 7.28 (bs, 2H, 6-NH2), 7.21 (s, 1H, 8-H).

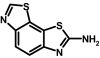

Compound 39 (SKA-25) was prepared from 6-aminobenzothiazole (2 g, 13.3 mmol), potassium thiocyanate (5.2 g, 53.3 mmol), and liquid bromine (2.4 g, 14.7 mmol) according to general method I. The product was isolated as an off-white solid (120 mg, 4.3%); m.p. = 295.4°C (CAS 18505-09-4).

Compound 40 (SKA-56) was prepared from 3-aminoquinoline (250 mg, 1.7 mmol), ammonium thiocyanate (133.1 mg, 1.7 mmol), and benzyl trimethyl ammonium tribromide (697.1 mg, 1.8 mmol) according to general method II. The final product was isolated as a yellow solid (89 mg, 25%); m.p. =>380°C (CAS 143667-61-2). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ [ppm] = 8.9 (s, 1H, 4-H), 8.0 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.35 Hz, 6-H), 7.8 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 7.84 (d, 1H, 9-H), 7.6 (t, 2H, 3J = 2.51 Hz, 7-H, 8-H).

Cells, Cell Lines, and Clones. HEK-293 cells stably expressing hKCa2.1, rKCa2.2, and hKCa3.1 were obtained from Khaled Houamed, University of Chicago (Chicago, IL). The cloning of hKCa2.3 (19 CAG repeats) and hKCa3.1 has been described previously (Wulff et al., 2000). The hKCa2.3 clone was later stably expressed in COS-7 cells at Aurora Biosciences Corporation (San Diego, CA). Cell lines stably expressing other mammalian ion channels were gifts from several sources: hKCa1.1 in HEK-293 cells (Andrew Tinker, University College London, London, UK); rKv4.2 in LTK cells (Michael Tamkun, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO); Kv11.1 (HERG) in HEK-293 cells (Craig January, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI); hNav1.4 in HEK-293 cells (Frank Lehmann-Horn, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany), and Cav1.2 in HEK-293 cells (Franz Hofmann, Munich, Germany). Cells stably expressing mKv1.1, mKv1.3, hKv1.5, and mKv3.1 have been described previously (Grissmer et al., 1994); N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells (expressing Nav1.2) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Rat Kv3.2 in pcDNA3 was obtained from Protinac GmbH (Hamburg, Germany). Rat Nav1.5 in pSP64T was provided by Roland G. Kallen (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) and the HindIII/HindIII fragment containing the entire Nav1.5 coding sequence was inserted into HindIII-digested pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The correct orientation of the coding sequence was verified by restriction analysis. Both clones were transiently transfected into COS-7 cells together with eGFP-C1 with Fugene-6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Electrophysiology. All experiments were conducted with an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) in the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique with a holding potential of -80 mV. Pipette resistances averaged 2.0 MΩ. Solutions of benzothiazoles in Na+ aspartate Ringer were freshly prepared during the experiments from 1 or 10 mM stock solutions in DMSO. The final DMSO concentration never exceeded 1%. For measurements of KCa2 and KCa3.1 currents, we used an internal pipette solution containing 145 mM K+ aspartate, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM K2EGTA, and 5.96 (250 nM free Ca2+) or 8.55 mM CaCl2 (1 μM free Ca2+), pH 7.2, 290 to 310 mOsm. Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated with MaxChelator assuming a temperature of 25°C, a pH of 7.2, and an ionic strength of 160 mM. To reduce currents from native chloride channels in COS-7 and HEK-293 cells, Na+ aspartate Ringer was used as an external solution: 160 mM Na+ aspartate, 4.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 290-310 mOsm. KCa2 and KCa3.1 currents were elicited by 200-ms voltage ramps from -120 to 40 mV applied every 10 s, and the -fold increase of slope conductance at -80 mV by drug was taken as a measure of channel activation.

KCa1.1 currents were elicited by 200-ms voltage steps from -80 to 60 mV applied every 10 s (1 μM free Ca2+), and channel modulation was measured as a change in mean current amplitude. Kv1.1, Kv1.3, Kv1.5, Kv3.1, Kv3.2, and Kv4.2 currents were recorded in normal Ringer solution with a Ca2+-free KF-based pipette solution as described previously (Schmitz et al., 2005). HERG (Kv11.1) currents were recorded with a 2-step pulse from -80 first to 20 mV for 2 s and then to -50 mV for 2 s, and the reduction of both peak and tail current by the drug was determined. Nav1.2 currents from N1E-115 cells, Nav1.4 currents from stably transfected HEK cells, and Nav1.5 currents from transiently transfected COS-7 cells were recorded with 20-ms pulses from -80 mV to -10 mV every 10 s with a KCl-based pipette solution and normal Ringer as an external solution. Cav1.2 currents were elicited by 600-ms depolarizing pulses from -80 to 20 mV every 10 s with a CsCl-based pipette solution and an external solution containing 30 mM BaCl2. Blockade of both Na+ and Ca2+ currents was determined as a reduction of the current minimum.

Cytotoxicity Assays. Jurkat E61 and MEL cells were seeded at 105 cells/ml in 12-well plates. SKA-31 and SKA-20 were added at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM in a final DMSO concentration of 0.1%, which was found not to affect cell viability. After 48 h, the cells in each well were well mixed and resuspended, and the number of trypan blue-positive cells in three aliquots from each well was determined under a light microscope. The test was repeated twice.

NMDA Receptor Radioligand Binding Assay. Riluzole, SKA-20, and SKA-31 were tested by MDS Pharma Services (Taipei, Taiwan) for binding to the kainate (ligand 5 nM [3H]kainic acid), glutamate (ligand 2 nM [3H]CGP-39653), and glycine (ligand 0.33 nM [3H]MDL105519) binding sites of rat brain NMDA receptors.

Pharmacokinetics and HPLC/MS Assay. Nine- to eleven-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed in microisolator cages with rodent chow and autoclaved water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the University of California, Davis, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For intravenous injection, SKA-31 was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in a mixture of 10% Cremophor EL and 90% saline and injected at 10 mg/kg. For intraperitoneal application, SKA-31 was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in Miglyol 812 neutral oil (caprylic/capric triglyceride; Neebee M5, Spectrum Chemicals, Gardena, CA). After tail vein injection of the aqueous solution or intraperitoneal administration of the oily solution, approximately 200 μl of blood was collected from the tail into EDTA blood sample collection tubes at various time points. For very early time points (3, 5, and 10 min) after intravenous administration, blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture under deep isoflurane anesthesia. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at -80°C pending analysis. After determining that SKA-31 plasma concentrations peaked 2 h after application (10 mg/kg i.p.), we took blood samples under deep isoflurane anesthesia by cardiac puncture from a group of three rats before sacrificing the animals to remove brain, heart, liver, spleen, and fat. Tissue samples were homogenized in 1 ml of H2O with a Brinkmann Kinematica PT 1600E homogenizer (Kinematica, Littau-Lucerne, Switzerland), and the protein was precipitated with 1 ml of acetonitrile. The samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm, and supernatants were concentrated to 1 ml. Plasma and homogenized tissue samples were purified using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges. Elution fractions corresponding to SKA-31 were evaporated to dryness under nitrogen and dissolved in acetonitrile.

LC/MS analysis was performed with a Hewlett Packard 1100 series HPLC stack (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a Merck KGaA RT 250-4 LiChrosorb RP-18 column (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ) interfaced to a Finnigan LCQ Classic MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/water with 0.2% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and the gradient was ramped from 80/20 for 5 min to 70/30 over 15 min. With the column temperature maintained at 30°C, SKA-31 eluted at 5.7 min and was detected with a variable wavelength detector set to 254 nm and the MS in series. Using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (capillary temperature, 350°C; capillary voltage, 26 V; tube lens offset, 20V; positive ion mode), SKA-31 was detected at a mass of 201.35 (molecular weight plus H+). SKA-31 concentrations were calculated with a five-point calibration curve from 500 nM to 8 μM. Concentrations greater than 1 μM were determined by their UV absorption using a second calibration curve from 1 to 250 μM. Riluzole (retention time, 13.5 min; mass, 235.35, molecular weight plus H+) was used as an internal standard.

The percentage of plasma protein binding for SKA-31 was determined by ultrafiltration. Rat plasma was spiked with 10 μM SKA-31 in 1% DMSO, and the sample was loaded onto a Microcon YM-100 Centrifugal Filter (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA) and centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 15 min at RT. The centrifugate (free SKA-31) was directly analyzed for SKA-31 by HPLC-MS. The retentate was collected by inverting the filter into an Eppendorf tube and spinning at 14000 rpm for 15 min. The retentate then underwent sample preparation according to the above-described procedure for determining total SKA-31 concentration in plasma. The plasma protein binding of SKA-31 was found to be 39 ± 0.8% (n = 3). The unbound (free) fraction was 61 ± 1.7%.

Mice, Carotid Artery Preparation, and Isolation of Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells. Wild-type (WT) and KCa3.1(-/-) mice (Si et al., 2006) of both genders (16-25 weeks old) were derived from our own breeding colonies at the University of Marburg (Marburg, Germany) in a specific-pathogen-free environment. All experiments were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care committee. The preparation of carotid arteries (CAs) from mice and the isolation of CAEC were performed as described previously (Si et al., 2006). In brief, freshly isolated CAs were mounted on glass capillaries and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) without Ca2+/Mg2+ to remove remaining blood cells. Then CAs were filled with 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA in PBS without Ca2+/Mg2+ via the glass capillary, sutured, and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Thereafter, CAs were cut open longitudinally under microscopic control, and CAECs were detached by gently scraping the luminal face of CA. Patch-clamp experiments in these CAEC were conducted within 2 to 4 h.

CAEC Electrophysiology. Membrane currents in CAEC from WT and KCa3.1(-/-) mice were recorded with an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA) using voltage ramps (1000 ms; -120 to 40 mV). The standard KCl-pipette solution for whole-cell patch-clamp experiments contained 140 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 1.2 mM CaCl2, (0.25 μM [Ca2+]free), and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2. The standard NaCl bath solution contained 137 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 0.7 mM CaCl2 (< 0.1 μM [Ca2+]free), and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH. To unmask KCa3.1 currents from KCa2.3 currents in wild-type CAECs, experiments were performed in the presence of 1 μM concentration of the KCa2.3 blocker UCL1684 (Rosa et al., 1998). KCa2.3 currents were recorded from KCa3.1(-/-) CAEC. UCL1684 was obtained from Biotrend AG (Wangen, Zürich, Switzerland); all other standard chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (München, Germany). Data analysis was performed as described previously (Si et al., 2006). Endothelial cell TREK-1 (K2P2.1) currents were recorded as recently described by us (Pokojski et al., 2008).

Pressure Myography. Pressure myography in CAs from KCa3.1(-/-) and wild-type mice was performed as described previously (Si et al., 2006). Bath and perfusion solutions contained 145 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, 2 mM pyruvate, and 3 mM MOPS buffer, pH 7.4, at 37°C. To suppress nitric oxide (NO) or prostacyclin synthesis, the solution contained additionally the NO synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine (300 μM) and the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (10 μM). After mounting on glass capillaries, CAs were pressurized to 80 mm Hg and were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min. Thereafter, CAs were preconstricted with 1 μM phenylephrine and were continuously perfused at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The endothelium was stimulated for 15 s with acetylcholine (ACh; 0.1 μM) alone or in combination with SKA-31 (0.1 nM to 1 μM) in the perfusion solution. Diameter changes of CA were expressed as a percentage of the maximal dilation to 10 μM sodium nitroprusside.

Telemetry. Telemetric pressure measurements were performed as described previously (Gross et al., 2000; Si et al., 2006). After implantation of a TA11PA-C20 pressure transducer (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) into the left carotid artery, WT and KCa3.1(-/-) mice were allowed to recover for at least 9 days to regain a normal circadian rhythm. Thereafter, systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were monitored continuously using the DATAQUEST software (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN). Values were analyzed as 24 h means. SKA-31 was dissolved in peanut oil, and 1, 10, or 30 mg/kg i.p. was injected in a volume of 100 μl at the end of the light period (at 7 P.M.). Peanut oil as a vehicle had no effects on MAP (data not shown). In a separate set of experiments, WT mice (n = 5) mice were continuously infused with angiotensin II (1.2 mg/kg/d s.c. via implanted minipumps). After development of hypertension (normally after 2 days), 30 mg/kg i.p. SKA-31 was injected. From a group of WT mice injected with 10 mg/kg SKA-31, blood samples were collected at 30 min and at 1, 2, 4, and 24 h (four animals per time point). Plasma was separated by centrifugation and SKA-31 concentrations were determined by HPLC/MS (see above).

Statistical Analysis. Pharmacokinetic data and EC50 values are given as mean ± S.D. Telemetry and pressure myography data are given as mean ± S.E.M. The unpaired or paired Student's t test was used to assess differences between groups as indicated. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Probing of the Benzothiazole Pharmacophore for KCa Channel Activation. Of the existing KCa2/3 channel activators (Fig. 1A), we chose the benzothiazole riluzole as a template for the design of a new KCa2/3 channel activator because benzothiazoles are clearly “privileged” chemical structures that can exert multiple pharmacological activities if “appropriately decorated with substituents” (Evans et al., 1988; Horton et al., 2003). (The concept of a “privileged structure refers to structural types capable of binding to multiple classes of receptors, ion channels or enzymes with high affinity. “Privileged” structures are typically constrained, heterocyclic, multiring systems capable of orientating varied substituent patterns in a well defined 3-D space. Well known examples of “privileged” structures are benzodiazepines and dihydropyridines.) Another consideration for preferring riluzole over EBIO as a template despite its pharmacological “dirtiness” was the fact that riluzole, which is an U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has good pharmacokinetic properties (Colovic et al., 2004). It therefore seemed reasonable to assume that riluzole derivatives would exhibit similar drug-like properties and could potentially be used as tools to investigate the effects of KCa2/3 channel activation in vivo.

Similar to EBIO and NS309, riluzole has been reported to increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2/3 channels, resulting in an apparent leftward shift of their Ca2+ activation curve (Grunnet et al., 2001; Pedarzani et al., 2001; Cao et al., 2002). The magnitude of riluzole's activating effect therefore depends on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. However, it should be mentioned here that data from the group of Daniel Devor suggest that EBIO and the muscle-relaxant chlorzoxazone increase KCa2/3 channel open probability rather then Ca2+ sensitivity (Syme et al., 2000). In our hands, riluzole increased KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 currents in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments roughly 3-fold with 1 μM [Ca2+]i (data not shown) and 30-fold with 250 nM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1B). We therefore decided to screen for more potent riluzole derivatives with 250 nM [Ca2+]i to obtain larger and more easily detectable current increases. We further decided to perform the initial screen at just three concentrations (1, 10, and 100 μM) on KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 either transiently or stably expressed in COS-7 or HEK-293 cells because we only have a manual patch-clamp setup and no high-throughput electrophysiology screening system in our laboratory. Because benzothiazoles have been previously studied as central muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, and neuroprotective agents and are further widely used as diazocomponents in monoazo disperse dyes, we performed a similarity search in the Chemical Abstract System for commercially available compounds before embarking on the synthesis of new riluzole derivatives. In total, we purchased 24 benzothiazoles, which we deemed worthwhile screening for exploring the structure-activity relationship for KCa2/3 channel activation. Another 17 benzothiazoles were synthesized according to the general methods depicted in Fig. 2A. The overall goal of our synthetic strategy was first to probe all positions of the benzothiazole ring system to characterize the structural elements that are necessary for KCa2/3 channel activation and then to improve activity if possible. As shown in Fig. 2B, we first varied the 2-aminobenzothiazole system itself by inverting the positions of the nitrogen and sulfur atoms and then introduced various functional groups or ring systems in positions 4, 5, 6, and 7. Replacement of the 1-position sulfur atom with nitrogen, replacement of the 2-amino group with an -SH group, or of both moieties resulted in compounds that were more than 10 times less potent than riluzole (compounds 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in Table 1). Opening of the benzothiazole system to a 4-(4-trifluoromethoxyphenyl)thiazol-2-ylamine also drastically reduced potency (compound 7 in Table 1). Taken together, these results demonstrate that KCa2/3 channel activators of the benzothiazole class require an intact 2-aminobenzothiazole system to show significant activity at or below 10 μM.

TABLE 1.

Results of screening benzothiazoles varied in positions 1 and 2 on KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μM

The reported numbers are the ratios of slope conductance at −80 mV measured in the presence and absence of drug with 250 nM [Ca2+]i.

N.E., no effect; N.D., not determined.

We next removed the lipophilic 6-position -OCF3 group of riluzole or replaced it with other functional groups (Table 2). Complete removal of the group (8) or replacement with polar functional groups such as -NH2, -NO2, -CH3SO2, or -COCH3 significantly reduced activity (compounds 9-12 in Table 2). Replacement of the -OCF3 group with a less lipophilic -OCH3 group (13) or a more bulky benzyl (16), phenoxy (17), or benzoyl (18) group also reduced or completely removed KCa2/3 channel activation. In contrast, introduction of two -CH3 groups (19) or the halogen atoms fluorine (20 and 21) or chlorine (22) in the 5,6- or 6-position alone resulted in compounds that were roughly as potent as riluzole (Table 2). We next decided to make more subtle variations of the -OCF3 group. However, moving the -OCF3 group from position 6 to position 5 or 4 (23 and 24), removal of the oxygen atom (25 and 26), replacement of the oxygen with a sulfur atom (27), or replacement of one of the three fluorine atoms with chlorine (28) also did not improve activity in comparison with riluzole (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Screening of 4, 5, and 6 position-substituted benzothiazoles on KCa2.3 and KCa3.1

The reported numbers are the ratios of slope conductance at −80 mV measured in the presence and absence of drug with 250 nM [Ca2+]i.

N.E., no effect; N.D., not determined.

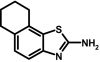

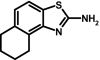

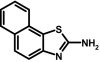

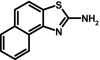

Because introduction of simple functional groups in any position of the benzothiazole system did not improve potency, we next introduced larger annulated aliphatic and aromatic ring systems (Table 3). Although a cyclopentyl ring in 5,6-position (30) did not improve potency, a cyclohexyl ring in 6,7-position (31) or in 4,5-position (32) increased potency roughly 2-fold. Potency further improved when aromatic systems such as phenyl (33 and 34) or naphthyl (35) were introduced in positions 4,5 or 6,7. However, the introduction of polar carbonyl functions as in 36 or 37 or the introduction of heteroatoms into the aromatic or aliphatic ring systems as in 38, 39, 40, and 41 again drastically reduced potency (Table 3). The most potent compounds in our library, 33 (SKA-45), 34 (SKA-31), and 35 (SKA-20), activated KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 currents roughly 10-fold more potently than riluzole and displayed the same preference for KCa3.1 over KCa2.3. Of these three compounds, we decided to further characterize SKA-20 and SKA-31 because of the much higher costs of the starting materials for SKA-45.

TABLE 3.

Screening of annulated benzothiazoles on KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 at 1, 10, and 100 μM

The reported numbers are the ratios of slope conductance at −80 mV measured in the presence and absence of drug with 250 nM [Ca2+]i.

N.E., no effect; N.D., not determined.

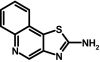

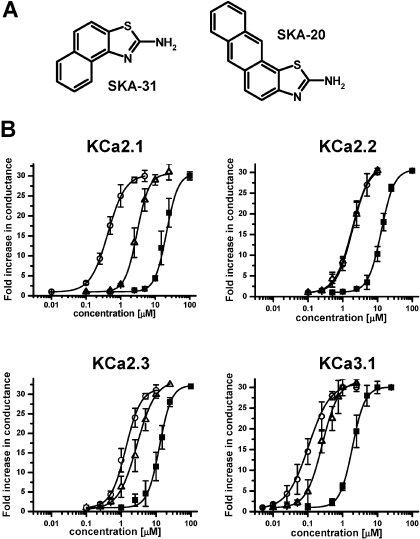

SKA-20 and SKA-31 Activate KCa2/3 Channels More Potently than Riluzole and Are More Selective over Other Ion Channels. To compare the potency of riluzole, SKA-20, and SKA-31 (Fig. 3A), we determined seven-point concentration-response curves on KCa2.1, KCa2.2, KCa2.3, and KCa3.1 with 250 nM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3B). The template riluzole activated KCa3.1 with an EC50 value of 1.9 μM and was 6 to 10 times less potent on KCa2.1 (EC50 value, 21 μM), KCa2.2 (EC50 value, 12.8 μM), and KCa2.3 (EC50 value, 12.5 μM). SKA-20 and SKA-31 were also most active on KCa3.1 and exhibited EC50 values of 115 and 260 nM for this channel (Fig. 3B). Both compounds were equally potent on KCa2.2 (EC50 value, 1.9 μM). However, SKA-20 and SKA-31 differed in their EC50 values for KCa2.1 and KCa2.3. Although SKA-31 activated both KCa2.1 and KCa2.3 with an EC50 value of 2.9 μM, SKA-20 showed roughly 3-fold higher activity on KCa2.1 (EC50 value, 430 nM) than on KCa2.3 (EC50 value, 1.2 μM). In agreement with studies performed previously on EBIO, NS309, and riluzole (Wulff et al., 2007), SKA-31 activated KCa3.1, and KCa2.3 currents were inhibited by the pore blockers TRAM-34, charybdotoxin, and apamin with their normal concentration-response relationship (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, the “negative” KCa2 channel gating modulator NS8593 (Strøbæk et al., 2006) inhibited SKA-31-activated KCa2.3 currents with a roughly 10-fold higher IC50 (7 μM instead of 700 nM), suggesting competition between the “positive” and “negative” gating-modulators (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for the effect of NS8593 in the absence of SKA-31).

Fig. 3.

SKA-31 and SKA-20 are potent KCa channel activators. A, chemical structures of SKA-31 and SKA-20. B, concentration-response curves for riluzole (▪), SKA-31 (▵), and SKA-20 (○) on hKCa2.1, rKCa2.2, hKCa2.3, and hKCa3.1 stably expressed in HEK-293 cells (n = 3-6 per data point). KCa2.1: riluzole: EC50, 21 ± 3 μM, nH, 2.5; SKA-20: EC50, 430 ± 100 nM; nH, 1.7; SKA-31: 2.9 ± 0.4 μM; nH 2.3; KCa2.2: riluzole: EC50, 12.8 ± 0.7 μM; nH, 2.3; SKA-20: EC50, 1.9 ± 0.3 μM; nH, 1.8; SKA-31: EC50, 1.9 ± 0.4 μM; nH, 1.7; KCa2.3: riluzole, EC50, 12.5 ± 1.2 μM; nH, 2.4; SKA-20: EC50, 1.2 ± 0.4 μM; nH, 1.9; SKA-31: 2.9 ± 0.7 μM; nH 1.7; KCa3.1: riluzole: EC50, 1.9 ± 0.3 μM; nH, 2.3; SKA-20: EC50, 115 ± 24 nM; nH, 1.6; SKA-31: EC50, 260 ± 40 nM; nH, 1.8.

Fig. 4.

A, blockade of hKCa3.1 currents activated with 2.5 μM SKA-31 by increasing concentrations of TRAM-34 or charybdotoxin. B, blockade of hKCa2.3 currents activated with 10 μM SKA-31 by increasing concentrations of apamin and NS8593. Note that the IC50 values of the pore blockers TRAM-34 (∼20 nM), charybdotoxin (∼5 nM), and apamin (∼1 nM) are unchanged, whereas the IC50 value of the negative gating modulator NS8593 is shifted roughly 10-fold to the right indicating competition. All experiments were performed with an aspartate-based pipette solution containing 250 nM free Ca2+. The external solution is aspartate Ringer.

We next compared the selectivity of riluzole, SKA-20, and SKA-31 on a panel of 13 K+,Na+, and Ca2+ channels. In agreement with previous publications (Zona et al., 1998; Ahn et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008), riluzole activated KCa1.1 and K2P2.1 channels and blocked Kv1, Kv3, Kv4, and Kv11.1 (HERG) channels with IC50 values of 50 to 130 μM (Table 4). At the highest possible (dissolvable) test concentrations, SKA-20 and SKA-31 either had no effect or blocked these channels by only 10 to 30%. SKA-20 and SKA-31 also exhibited a better selectivity over Na+ and Ca2+ channels. Although riluzole blocked neuronal Nav1.2 (IC50 value, 15 μM), skeletal muscle Nav1.4 (IC50 value, 9 μM), cardiac Nav1.5 (IC50 value, 8 μM), and Cav1.2 (IC50 value, 30 μM) channels at roughly the same concentrations at which it activates KCa2/3 channels (EC50 values, 2-21 μM), SKA-31 at 25 μM either had no effect (Cav1.2) or exhibited only 14 to 40% blockade (Nav channels). The more lipophilic SKA-20 (logP 3.1), in contrast, blocked Nav1.2 channels as potently as riluzole. In a radioligand binding assay testing for affinity to rat brain kainate, glutamate, and glycine binding sites, SKA-20 further exhibited a Ki value of 19 μM for the glutamate site of NMDA receptors, whereas SKA-31 (25 μM) and riluzole (100 μM) had no effect (data not shown; performed by MDS Pharma Services, King of Prussia, PA). Based on its higher selectivity and its lower logP value of 2.2, we selected SKA-31 for subsequent experiments.

TABLE 4.

Selectivity

| Channel | Riluzole IC50 | 10 μM SKA-20 | 25 μM SKA-31 |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| KCa1.1 | Doubles current at 100 μM | N.E. | N.E. |

| Kv1.1 | 92 ± 7 | 12 ± 3% block | N.E. |

| Kv1.3 | 50 ± 5 | 12 ± 2% block | 20 ± 5% block |

| Kv1.5 | 95 ± 5 | 25 ± 3% block | 20 ± 5% block |

| Kv3.1 | 95 ± 5 | 35 ± 3% block | 30 ± 5% block |

| Kv3.2 | 100 ± 10 | 12 ± 5% block | 15 ± 3% block |

| Kv4.2 | 130 ± 10 | 10 ± 3% block | N.E. |

| Kv11.1 (HERG) | 50 ± 4 | N.D. | N.E. |

| K2P2.1 (TREK-1) | 110 ± 35* | N.E. | N.E. |

| Nav1.2 | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 2 μM | 9 ± 5% block |

| Nav1.4 | 9 ± 2 | N.E. | 20 ± 5% block |

| Nav1.5 | 8 ± 2 | 30 ± 5% block | 40 ± 5% block |

| Cav1.2 | 30 ± 3 | N.E. | N.E. |

N.E., no effect; N.D., not determined.

EC50 (riluzole activates K2P2.1 currents).

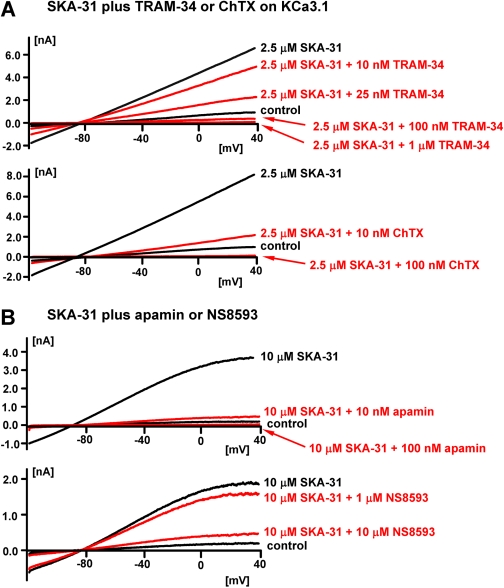

SKA-31 Is Not Acutely Toxic and Has Good Pharmacokinetic Properties. Similar to riluzole, SKA-31 was not cytotoxic at concentrations up to 100 μM (data not shown) and did not induce any signs of acute toxicity when administered at doses of 10 or 30 mg/kg i.p. to male Sprague-Dawley rats. We therefore next established a HPLC/MS assay to determine SKA-31 plasma and tissue concentrations. After intravenous administration at 10 mg/kg in rats, total SKA-31 plasma concentrations decreased from a peak of 30 μM at 3 min to 5 μM at 1 h, 2.5 μM at 24 h, and 2 μM at 48 and 80 h (Fig. 5A). This decay in plasma levels was best fitted triexponentially, reflecting a three-compartment model with very rapid distribution from blood into tissue followed by elimination with a half-life of roughly 12 h and slow repartitioning from body tissues acting as a deep compartment back into plasma. After administration of 10 and 30 mg/kg i.p. to rats (Fig. 5B), total SKA-31 concentrations peaked at 2 h, reaching 25 and 37 μM, and then decreased to 2 μM at 24 h. Tissue concentration determinations performed at the plasma peak (Fig. 5C) revealed that SKA-31 effectively penetrates into tissue (especially into the brain) but that plasma concentrations are, on average, 4- to 8-fold higher than tissue concentrations. In mice (Fig. 5D), we obtained slightly lower plasma concentrations than in rats (5.5 μM at 2 h, 1.4 μM at 4 h, and 500 nM at 24 h with 10 mg/kg i.p.). We further determined the plasma protein binding of SKA-31 and found that 39% was protein-bound and 61% was free and thus available to modulate KCa3/2 channels. Taken together, these results show that SKA-31 is not acutely toxic and has good pharmacokinetic properties. The fact that the highest SKA-31 concentrations are found in plasma and not in tissue also suggests that SKA-31 might preferentially target KCa2/3 channels located on the vascular endothelium.

Fig. 5.

Pharmacokinetics of SKA-31. A, total SKA-31 plasma concentrations (mean ± S.D.) after intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg in Cremophor EL/PBS to male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 4). The inset shows the first 24 h. The data are best-fitted as triexponential decay in keeping with a three-compartment model. B, total SKA-31 plasma concentrations after administration of 10 and 30 mg/kg i.p. in Miglyol 812 (1 μl per gram of body weight) to male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3). C, table showing plasma and tissue concentrations at 2 h after administration of 10 mg/kg i.p. SKA-31 to male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3). D, total SKA-31 plasma concentration after administration of 10 mg/kg i.p. in peanut oil (2 μl per gram of body weight) to mice (n = 5-8).

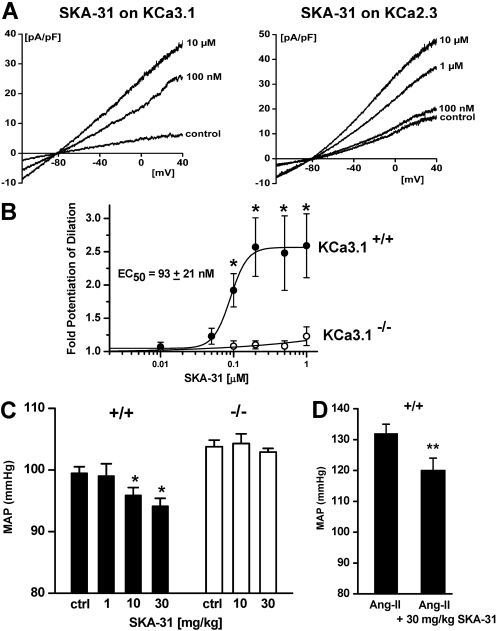

SKA-31 Stimulates KCa3.1 and KCa2.3 in Vascular Endothelial Cells and Increases ACh-Induced EDHF-Mediated Vasodilation. Vascular endothelial cells express KCa3.1 and KCa2.3 channels, and the activation of these channels leads to endothelial hyperpolarization and subsequently to vascular smooth muscle cell relaxation, the so-called EDHF response (Edwards et al., 1998; Eichler et al., 2003; Köhler and Hoyer, 2007). Similar to their actions on the cloned human channels, SKA-31 and SKA-20 potentiated native KCa3.1 and KCa2.3 in murine carotid endothelium with EC50 values of 225 (SKA-31) and 142 nM (SKA-20) for KCa3.1 and with EC50 values of 1.6 (SKA-31) and 1.5 μM (SKA-20) for KCa2.3 (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

Fig. 6.

SKA-31 potentiates EDHF-type vasodilations and lowers blood pressure in mice. A, effect of increasing concentrations of SKA-31 on native KCa3.1 or KCa2.3 in mouse CAEC. KCa3.1 currents we recorded from WT mice with KCa2.3 blocked by 1 μM UCL1684; KCa2.3 currents were recorded from KCa3.1(-/-) CAEC. B, SKA-31 potentiates carotid artery dilation (EDHF-type) in response to 100 nM ACh in WT mice (KCa3.1(+/+); n = 3-7 arteries per data point) but not in KCa3.1(-/-) mice (n = 2-5 arteries per data point). C, telemetry: single injections of SKA-31 at 1, 10, and 30 mg/kg i.p. lower MAP over 24 h in normotensive WT mice (+/+) but not in KCa3.1(-/-) mice (-/-). Control, baseline MAP over 24 h before SKA-31 injection [WT (9 animals): control 99.5 ± 1.0 mm Hg (14 measurements); 1 mg/kg SKA-31 99.0 ± 2.0 mm Hg (two measurements); 10 mg/kg SKA-31 95.8 ± 1.3 mm Hg (seven measurements, P = 0.006 versus control); 30 mg/kg SKA-31 94.1 ± 1.3 mm Hg (five measurements, P = 0.0003); KCa3.1(-/-) (5 animals): control 103.7 ± 1.1 mm Hg (five measurements, P = 0.006 versus WT); 10 mg/kg SKA-31 104.3 ± 1.5 mm Hg (five measurements, P, not significant); 30 mg/kg SKA-31 102.9 ± 0.6 mm Hg (three measurements)]. After a washout period of 3 to 6 days, some animals were reused to test a second higher dose of 10 or 30 mg/kg SKA-31. D, SKA-31 (30 mg/kg i.p.) lowers MAP in angiotensin-II-induced hypertension (Ang-II) [WT (five animals): control 132 ± 3 mm Hg (n = 5); SKA-31 120 ± 4 mm Hg (n = 5, P = 0.0038)]. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

In pressure myography of murine CA, SKA-31 potentiated EDHF-type dilation elicited by 100 nM acetylcholine with an EC50 value of 93 nM (Fig. 6B) and induced a 2- to 3-fold increase in dilation at the highest dose of SKA-31 (1 μM) tested. In the absence of acetylcholine, SKA-31 did not dilate or contract CAs at concentrations of 0.01 to 1 μM (data not shown). In CAs of KCa3.1(-/-) mice (Si et al., 2006), SKA-31 at concentrations of 0.1 to 1 μM did not potentiate the residual KCa2.3-mediated EDHF-type response (Fig. 6B), reflecting its 7- to 10-fold selectivity for KCa3.1 over KCa2.3. Taken together, our vessel studies show that SKA-31 effectively enhances EDHF-type dilations by predominantly acting on endothelial KCa3.1 channels.

KCa3.1 Activation with SKA-31 Lowers Mean Arterial Blood Pressure. Based on SKA-31's effect on endothelial KCa3.1 channels and thereby EDHF-type dilation in isolated blood vessels, we next tested whether in vivo administration of SKA-31 would lower arterial blood pressure. For this purpose, mice were implanted with telemetry leads, which allow continuous 24-h blood pressure measurements and heart rate monitoring, and then injected them with SKA-31. A single administration of 10 mg/kg i.p. SKA-31 lowered MAP by 4 mm Hg over a period of 24 h (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. 3). Blood pressure values then returned to normal, reflecting a decrease in the plasma concentration of “free” (not plasma protein-bound) SKA-31 below the EC50 value for KCa3.1 activation after 24 h (Fig. 5D; 500 nM total SKA-31 in plasma at 24 h will result in a “free” SKA-31 concentration of 300 nM). A higher dose of 30 mg/kg SKA-31 lowered MAP by 6 mm Hg (Fig. 6C), whereas 1 mg/kg SKA-31 was ineffective (Fig. 6C), presumably because it does not achieve pharmacologically active plasma levels. In KCa3.1(-/-) mice, which exhibit a 5 mm Hg higher MAP compared with WT mice due to the impaired EDHF response in the absence of KCa3.1 (Si et al., 2006), SKA-31 at 10 and 30 mg/kg had no blood pressure-lowering effects (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. 3), demonstrating that SKA-31 exerts its blood pressure-lowering effects through KCa3.1 channel activation. Because SKA-31 administration induced a moderate but significant reduction in MAP in “normal” mice (see Fig. 6 legend for P values), we next investigated whether KCa3.1 channel activation could also lower MAP in hypertensive animals. We therefore induced hypertension in WT mice by administering the potent endogenous vasoconstrictor angiotensin-II (1.2 mg/kg/day) continuously via implanted minipumps and then treated the mice with SKA-31 after hypertension had developed. SKA-31 at 30 mg/kg lowered MAP by 12 mm Hg (Fig. 6D). SKA-31 did not alter heart rate in any of the groups (Supplementary Fig. 4). Taken together, our findings support the notion that the potentiating effects of SKA-31 on endothelium-dependent dilations and its blood pressure-lowering actions are mediated through activation of endothelial KCa3.1 channels but not by dampening cardiac functions.

Discussion

We here used the “old drug” riluzole as a template for the design of a novel KCa2/3 channel activator that is potent and selective enough to probe the therapeutic potential of KCa2/3 channel activation in vivo. Our identification of SKA-31 is another example of how a “privileged” chemical structure such as riluzole's benzothiazole core can exert multiple pharmacological activities if substituted appropriately (Evans et al., 1988; Horton et al., 2003). Our strategy here was not to combine combinatorial chemistry with high-throughput screening but instead to start by testing a carefully selected small library of benzothiazoles and then modifying the synthetic strategy based on the results of the electrophysiological testing. Using this “classic” medicinal chemistry approach, we here explored the benzothiazole pharmacophore for KCa channel activation and were able to identify a novel KCa2/3 channel activator that is suitable for in vivo administration after testing only 41 compounds. The benzothiazole pharmacophore for KCa2/3 channel activation did not tolerate the introduction of hydrophilic substituents but proved to be relatively flexible in terms of molecular size and shape, because the annulation of both aromatic and aliphatic ring systems into 4,5- and 6,7-position resulted in high-affinity KCa2/3 channel activators. However, potency did not linearly correlate with logP (e.g., SKA-7 and SKA-22, which bear a phenyloxo- or a benzoyl-substituent in 6-position, are ineffective) demonstrating that the effect of the compounds is not due to unspecific membrane interactions. Our most drug-like molecule, SKA-31, is 10 times more potent than riluzole and activates cloned and native KCa3.1 channels with an EC50 value of 250 nM and all three KCa2 channels with EC50 values of 2 to 3 μM. In comparison to riluzole, SKA-31 further shows a significantly improved selectivity over other ion channels, particularly Na+ channels (Table 4). Although we did not characterize SKA-31's mechanism of action or its binding site in detail, the compound seems to work similarly to EBIO, NS309, and riluzole, which increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2/3 channels and thus their open probability by binding to an unidentified site located either in the C terminus of the channel or on the interface between the channel and the constitutively bound calmodulin (Pedarzani et al., 2001). In keeping with this hypothesis, SKA-31 reduced the effect of the “negative” gating modulator NS8593 (Strøbæk et al., 2006), which decreases the Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2 channels, but did not affect the potency of pore blockers such as ChTX, TRAM-34, or apamin. Similar to riluzole, SKA-31 only shows 7- to 10-fold selectivity for KCa3.1 over KCa2 channels but could serve as a new template for the future design of activators that can distinguish between KCa3.1 and the three KCa2 channel subtypes. The recently reported aminopyrimidine CyPPA from Neurosearch A/S (Ballerup, Denmark), which activates KCa2.3 and KCa2.2 currents with EC50 values of 6 and 14 μM but has no effect on KCa2.1 or KCa3.1 (Hougaard et al., 2007), demonstrates that this is in principle possible, although CyPPA has a much lower potency than SKA-31.

However, despite its moderate 7- to 10-fold selectivity for KCa3.1 over KCa2 channels, SKA-31 constitutes a valuable new pharmacological tool compound because of its potency and its excellent pharmacokinetic properties such as a long half-life and a low plasma protein binding. This assumption is supported by our demonstration that SKA-31 potentiated acetylcholine-induced EDHF-type dilations of mouse carotid arteries and significantly lowered blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive mice by activating endothelial KCa3.1 channels. Based on SKA-31's tissue distribution pattern (Fig. 5C), SKA-31 achieves the highest concentrations in the vasculature, where it can target endothelial KCa3.1 channels. SKA-31 could theoretically also activate endothelial KCa2.3 channels [which it indeed effectively activates at concentrations between 1 and 10 μM (Fig. 6A)], but the absence of a blood pressure-lowering effect in KCa3.1(-/-) mice (Fig. 6C) demonstrates that SKA-31 predominantly acts on endothelial KCa3.1 channels. However, if dosed higher, SKA-31 can activate KCa2 channels and can potentially also be used to explore the physiological consequences and the therapeutic potential of KCa2 channel activation. For example, based on the fact that EBIO and NS309 reduce neuronal firing by prolonging the medium after hyperpolarization in cultured hippocampal neurons or in brain slices (Pedarzani et al., 2001, 2005), KCa2 activators are widely regarded as potential new drugs for the treatment of central nervous system disorders characterized by hyperexcitability such as epilepsy, ataxia, and neuropathic pain (Wulff et al., 2007). To start exploring this therapeutic hypothesis, we submitted SKA-31 and SKA-29 (30) to the National Institutes of Health Anticonvulsant Screening Program (available at http://www.ninds.nih.gov/funding/research/asp/index.htm), where both compounds were found to effectively protect mice from seizures in the maximal and the 6-Hz minimal electroshock-induced seizure models at 15 min, 30 min, and 1 h after intraperitoneal application of 100 mg/kg. For these and other proof-of-concept experiments and for addressing the question of whether KCa2 activators will impair learning and memory as has been suggested based on the phenotype of transgenic mice overexpressing KCa2.2 (Hammond et al., 2006), SKA-31 constitutes a valuable new pharmacological tool compound. SKA-31 will be useful to address potential undesirable side effects of KCa3.1 channel activation, such as increases in Na+ absorption across cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells (Gao et al., 2001) or activation of proliferating smooth muscle cells, T cells, mast cells, or microglia. In all of these latter cell types, KCa3.1 blockers have been shown to inhibit proliferation, migration, and/or cytokine or reactive oxygen species production (Wulff et al., 2007), and it is currently not clear whether KCa3.1 activators will indeed have the opposite effects of blockers or whether the respective cells will counter-regulate.

Based on the in vivo experiments presented in our current study, we suggest activation of endothelial KCa3.1 channels as a new antihypertensive therapeutic approach. This approach might be particularly desirable in situations in which the EDHF response is impaired due to a decreased activity of endothelial KCa3.1 channels, as has been reported after cardiopulmonary bypass (Liu et al., 2008) and chronic renal failure (Kohler et al., 2005) and in various animal models of type-2 diabetes and hypertension (Köhler and Hoyer, 2007).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant R21-NS052165] and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [Grants from project A11 of SFB 593 and KO1899/10-1].

H.W. and R.K. contributed equally to this work.

ABBREVIATIONS: KCa, Ca2+-activated K+ channel; EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; ACh, acetylcholine; CA, carotid artery; CAEC, carotid artery endothelial cell; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; RT, room temperature; MS, mass spectrometry; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; HERG, human ether-a-go-go-related gene; HEK, human embryonic kidney; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; MOPS, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; WT, wild type; EBIO, 1-ethylbenzimidazolin-2-one; Kv, voltage-gated K+ channel; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NS8593, N-[(1R)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthalenyl]-1H-benzimidazol-2-amine hydrochloride; riluzole, 2-amino-6-[trifluoromethoxy]benzothiazole; SKA-1, 2-aminobenzothiazole; SKA-2, 2-amino-6-methoxybenzothiazole; SKA-3, 2-amino-6-chlorobenzothiazole; SKA-4, 2-amino-6-nitrobenzothiazole; SKA-5, 2-mercapto-5-methoxybenzothiazole; SKA-6, 2-amino-6-nitrobenzothiazole; SKA-7, 2-amino-6-benzylbenzothiazole; SKA-8, 2-amino-5-trifluoromethoxybenzothiazole; SKA-11, 2-amino-6-[chlorodifluoromethoxy]benzothiazole; SKA-12, 5-trifluoromethoxy-1H-benzimidazol-2-amine; SKA-13, 5-chloro-6-methoxy-benzothiazol-2-amine; SKA-16, 2-amino-6-[methylsulfonyl]benzothiazole; SKA-17, 5,6-dimethoxy-1,3-benzothiazol-2-amine; SKA-18, 2-amino-6-fluorobenzothiazole; SKA-19, 2-amino-6-trifluoromethylthio-benzothiazole; SKA-20, anthra[2,1-d]thiazol-2-ylamine; SKA-21, 2-amino-6,11-dihydro-6,11-dioxoanthra[2,1-d]-thiazole; SKA-22, 2-amino-6-benzoylbenzothiazole; SKA-24, 6-acetyl-2-aminobenzothiazole; SKA-25, 2-aminobenzo[1,2-d:4,3-d′]bisthiazole; SKA-26, 2-amino-7H-pyrano[2,3-g]benzothiazol-7-one; SKA-29, 6,7-dihydro-5H-indeno[5,6-d]thiazol-2-amine; SKA-30, 6,7-dihydro[1,4]dioxino[2,3-f]-[1,3]benzothiazol-2-amine; SKA-31, naphtho[1,2-a]thiazol-2-ylamine; SKA-32, 2-amino-6-phenoxybenzothiazole; SKA-34, 2-amino-5-trifluoromethyl)-benzothiazole; SKA-35, 2-amino-6-(trifluoromethoxy)benzothiazole; SKA-36, 2,6-diaminobenzothiazole; SKA-41, 4-(4-trifluoromethoxyphenyl)thiazol-2-amine; SKA-42, 2-amino-5,6-difluorobenzothiazole; SKA-44, 2-amino-6,7,8,9-tetrahydronaphtho[2,1-d]thiazole; SKA-45, naphtho[2,1-d]thiazol-2-amine; SKA-46, 5-trifluoromethoxy-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-thione; SKA-47, 5-[difluoromethoxy]-2-mercapto-1H-benzimidazole; SKA-48, 2-amino-5,6-dimethoxybenzothiazole; SKA-49, 6,7,8,9-tetrahydronaphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-amine; SKA-50, 2,6-diaminobenzo[1,2-d:4,5-d′]bisthiazole; SKA-51, 2-amino-6-[trifluoromethyl]benzothiazole; SKA-53, 2-amino-6-methyl-benzo[1,2-d. 5,4-d′]bisthiazole; SKA-56, thiazolo[4,5-c]quinolin-2-ylamine; UCL1684, 6,10-diaza-3(1,3),8(1,4)-dibenzena-1,5(1,4)-diquinolinacyclodecaphane; UCL1848, 8,14-diaza-1,7(1,4)-diquinolinacyclotetradecaphane; MDL105519, (E)-3-(2-phenyl-2-carboxyethenyl)-4,6-dichloro-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid; TRAM-34, 1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole; NS309, 6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime; CGP-39653, (E)-2-amino-4-propyl-5-phosphono-3-pentenoic acid; ICA-17043, bis(4-fluorophenyl)phenylacetamide.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Ahn HS, Choi JS, Choi BH, Kim MJ, Rhie DJ, Yoon SH, Jo YH, Kim MS, Sung KW, and Hahn SJ (2005) Inhibition of the cloned delayed rectifier K+ channels, Kv1.5 and Kv3.1, by riluzole. Neuroscience 133 1007-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YJ, Dreixler JC, Couey JJ, and Houamed KM (2002) Modulation of recombinant and native neuronal SK channels by the neuroprotective drug riluzole. Eur J Pharmacol 449 47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colovic M, Zennaro E, and Caccia S (2004) Liquid chromatographic assay for riluzole in mouse plasma and central nervous system tissues. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 803 305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono MW, Le Guern J, Canton T, Doble A, and Pradier L (1993) Inhibition by riluzole of electrophysiological responses mediated by rat kainate and NMDA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 235 283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor DC, Singh AK, Frizzell RA, and Bridges RJ (1996) Modulation of Cl- secretion by benzimidazolones. I. Direct activation of a Ca2+-dependent K+ channel. Am J Physiol 271 L775-L784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Unna KR, and Kerwin J (1952) Pharmacological properties of benzazoles. I. Relationship between structure and paralyzing action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 105 486-497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat F, Lesage F, Patel AJ, Fink M, Romey G, and Lazdunski M (2000) The neuroprotective agent riluzole activates the two P domain K+ channels TREK-1 and TRAAK. Mol Pharmacol 57 906-912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, and Weston AH (1998) K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature 396 269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler I, Wibawa J, Grgic I, Knorr A, Brakemeier S, Pries AR, Hoyer J, and Köhler R (2003) Selective blockade of endothelial Ca2+-activated small- and intermediate-conductance K+-channels suppresses EDHF-mediated vasodilation. Br J Pharmacol 138 594-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BE, Rittle KE, Bock MG, DiPardo RM, Freidinger RM, Whitter WL, Lundell GF, Veber DF, Anderson PS, and Chang RS (1988) Methods for drug discovery: development of potent, selective, orally effective cholecystokinin antagonists. J Med Chem 31 2235-2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger CM, Ghanshani S, Logsdon NJ, Rauer H, Kalman K, Zhou J, Beckingham K, Chandy KG, Cahalan MD, and Aiyar J (1999) Calmodulin mediates calcium-dependent activation of the intermediate conductance KCa channel, IKCa1. J Biol Chem 274 5746-5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I (2006) Realizing its potential: the intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (KCa3.1) and the regulation of blood pressure. Circ Res 99 462-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Yankaskas JR, Fuller CM, Sorscher EJ, Matalon S, Forman HJ, and Venglarik CJ (2001) Chlorzoxazone or 1-EBIO increases Na+ absorption across cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281 L1123-L1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, and Chandy KG (1994) Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 45 1227-1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross V, Milia AF, Plehm R, Inagami T, and Luft FC (2000) Long-term blood pressure telemetry in AT2 receptor-disrupted mice. J Hypertens 18 955-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunnet M, Jespersen T, Angelo K, Frøkjaer-Jensen C, Klaerke DA, Olesen SP, and Jensen BS (2001) Pharmacological modulation of SK3 channels. Neuropharmacology 40 879-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond RS, Bond CT, Strassmaier T, Ngo-Anh TJ, Adelman JP, Maylie J, and Stackman RW (2006) Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel type 2 (SK2) modulates hippocampal learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 26 1844-1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton DA, Bourne GT, and Smythe ML (2003) The combinatorial synthesis of bicyclic privileged structures or privileged substructures. Chem Rev 103 893-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard C, Eriksen BL, Jørgensen S, Johansen TH, Dyhring T, Madsen LS, Strøbaek D, and Christophersen P (2007) Selective positive modulation of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol 151 655-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimonet P, Audiau F, Barreau M, Blanchard JC, Boireau A, Bour Y, Coléno MA, Doble A, Doerflinger G, Huu CD, et al. (1999) Riluzole series. Synthesis and in vivo “antiglutamate” activity of 6-substituted-2-benzothiazolamines and 3-substituted-2-imino-benzothiazolines. J Med Chem 42 2828-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AD, Luo C, and Reitz AB (2003) Efficient conversion of substituted aryl thioureas to 2-aminobenzothiazoles using benzyltrimethylammonium tribromide. J Org Chem 68 8693-8696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajigaeshi S, Kakinami T, Tokiyama H, Hirakawa T, and Okamoto T (1987) Synthesis of dibromoacetyl derivatives by use of benzyltrimethylammonium tribromide. Bull Chem Soc Japan 60 2667-2668. [Google Scholar]

- Kajigaeshi S, Kakinami T, Yamasaki H, Fujisaki S, and Okamoto T (1988) Halogenation using quaternary ammonium polyhalides. XI. Bromination of acetanilides by use of tetraalkylammonium polyhalides. Bull Chem Soc Japan 61 2681-2683. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman HP (1928) Die Bildung von Thiazol-derivaten bei der Rodanierung von Aminen. Archiv Pharm 266 197-218. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler R, Eichler I, Schönfelder H, Grgic I, Heinau P, Si H, and Hoyer J (2005) Impaired EDHF-mediated vasodilation and function of endothelial Ca2+-activated K+ channels in uremic rats. Kidney Int 67 2280-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler R and Hoyer J (2007) The endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: insights from genetic animal models. Kidney Int 72 145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sellke EW, Feng J, Clements RT, Sodha NR, Khabbaz KR, Senthilnathan V, Alper SL, and Sellke FW (2008) Calcium-activated potassium channels contribute to human skeletal muscle microvascular endothelial dysfunction related to cardiopulmonary bypass. Surgery 144 239-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedarzani P, McCutcheon JE, Rogge G, Jensen BS, Christophersen P, Hougaard C, Strøbaek D, and Stocker M (2005) Specific enhancement of SK channel activity selectively potentiates the afterhyperpolarizing current IAHP and modulates the firing properties of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Biol Chem 280 41404-41411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedarzani P, Mosbacher J, Rivard A, Cingolani LA, Oliver D, Stocker M, Adelman JP, and Fakler B (2001) Control of electrical activity in central neurons by modulating the gating of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J Biol Chem 276 9762-9769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokojski S, Busch C, Grgic I, Kacik M, Salman W, Preisig-Müller R, Heyken WT, Daut J, Hoyer J, and Köhler R (2008) TWIK-related two-pore domain potassium channel TREK-1 in carotid endothelium of normotensive and hypertensive mice. Cardiovasc Res 79 80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa JC, Galanakis D, Ganellin CR, Dunn PM, and Jenkinson DH (1998) Bisquinolinium cyclophanes: 6,10-diaza-3(1,3),8(1,4)-dibenzena-1,5(1,4)-diquinolinacyclodecaphane (UCL 1684), the first nanomolar, non-peptidic blocker of the apamin-sensitive Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J Med Chem 41 2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Sankaranarayanan A, Azam P, Schmidt-Lassen K, Homerick D, Hänsel W, and Wulff H (2005) Design of PAP-1, a selective small molecule Kv1.3 blocker, for the suppression of effector memory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol 68 1254-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si H, Heyken WT, Wölfle SE, Tysiac M, Schubert R, Grgic I, Vilianovich L, Giebing G, Maier T, Gross V, et al. (2006) Impaired endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated dilations and increased blood pressure in mice deficient of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Circ Res 99 537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Syme CA, Singh AK, Devor DC, and Bridges RJ (2001) Benzimidazolone activators of chloride secretion: potential therapeutics for cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296 600-611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Huang CS, Nagata K, Yeh JZ, and Narahashi T (1997) Differential action of riluzole on tetrodotoxin-sensitive and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282 707-714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker M (2004) Ca2+-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat Rev Neurosci 5 758-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker M, Hirzel K, D'hoedt D, and Pedarzani P (2004) Matching molecules to function: neuronal Ca2+-activated K+ channels and following hyperpolarizations. Toxicon 43 933-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strøbaek D, Hougaard C, Johansen TH, Sørensen US, Nielsen EØ, Nielsen KS, Taylor RD, Pedarzani P, and Christophersen P (2006) Inhibitory gating modulation of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels by the synthetic compound (R)-N-(benzimidazol-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphtylamine (NS8593) reduces afterhyperpolarizing current in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Mol Pharmacol 70 1771-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strøbaek D, Teuber L, Jørgensen TD, Ahring PK, Kjaer K, Hansen RS, Olesen SP, Christophersen P, and Skaaning-Jensen B (2004) Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime). Biochim Biophys Acta 1665 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme CA, Gerlach AC, Singh AK, and Devor DC (2000) Pharmacological activation of cloned intermediate- and small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278 C570-C581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MS, Bonev AD, Gross TP, Eckman DM, Brayden JE, Bond CT, Adelman JP, and Nelson MT (2003) Altered expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK3) channels modulates arterial tone and blood pressure. Circ Res 93 124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YJ, Lin MW, Lin AA, and Wu SN (2008) Riluzole-induced block of voltagegated Na+ current and activation of BKCa channels in cultured differentiated human skeletal muscle cells. Life Sci 82 11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H, Kolski-Andreaco A, Sankaranarayanan A, Sabatier JM, and Shakkottai V (2007) Modulators of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and their therapeutic indications. Curr Med Chem 14 1437-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H, Miller MJ, Hansel W, Grissmer S, Cahalan MD, and Chandy KG (2000) Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, IKCa1: A potential immunosuppressant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 8151-8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia XM, Fakler B, Rivard A, Wayman G, Johnson-Pais T, Keen JE, Ishii T, Hirschberg B, Bond CT, Lutsenko S, et al. (1998) Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 395 503-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]