Abstract

The use of nanoparticles and ultrasound in medicine continues to evolve. Great strides have been made in the areas of producing micelles, nanoemulsions and solid nanoparticles that can be used in drug delivery. An effective nanocarrier allows for the delivery of a high concentration of potent medications to targeted tissue while minimizing the side effect of the agent to the rest of the body. Polymeric micelles have been shown to encapsulate therapeutic agents and maintain their structural integrity at lower concentrations. Ultrasound is currently being used in drug delivery as well as diagnostics, and has many advantages that elevate its importance in drug delivery. The technique is non-invasive, thus no surgery is needed; the ultrasonic waves can be easily controlled by advanced electronic technology so that they can be focused on the desired target volume. Additionally, the physics of ultrasound are widely used and well understood; thus ultrasonic application can be tailored towards a particular drug delivery system. In this article, we review the recent progress made in research that utilizes both polymeric micelles and ultrasonic power in drug delivery.

Keywords: Micelle, ultrasound, drug delivery, chemotherapy, cancer, surfactant, controlled release/delivery

1. Introduction

The high toxicity of potent chemotherapeutic agents limits the therapeutic window in which they can be utilized. This window can be expanded by controlling the drug delivery in both space (selective to the tumor volume) and time (timing and duration of release) such that non-targeted tissues are not adversely affected. Research in this area has focused on the synthesis of different drug depots that are capable of delivering a high concentration of chemotherapy drugs to cancerous tissues without affecting cells and organs in the systemic circulation. These depots can be broadly classified into three groups: liposomes, micelles and shelled vesicles. In this review we focus on the use of micelles in conjunction with ultrasound (US) to treat cancerous tissues. Low frequency ultrasound refers to frequencies less than 1 MHz, while the ranges for medium and high acoustic frequencies are 1-5 MHz and 5-10 MHz, respectively. We will present the advantages and disadvantages of such a drug delivery system, the recent advancements in this field, the future directions, and some unanswered questions that remain in this research topic; but first we will discuss the advantages of ultrasound.

2. Ultrasound in Drug Delivery

Using ultrasonic power as a drug release mechanism is advantageous for several reasons: First, the technique is non-invasive. The main advantage that renders ultrasound so useful is that no insertion or surgery is needed; acoustic transducers are placed in contact with a water-soluble gel that is spread on the skin. In addition, ultrasonic waves can penetrate deep into the interior of the body, an advantage that optical (visible wavelengths) techniques cannot provide. Ultrasonic waves can be carefully controlled and focused on the tumor site. Ultrasound consists of pressure waves (with frequencies of 20 kHz or greater) generated by piezoelectric transducers that change an applied voltage into mechanical movement. Like optical and audio waves, ultrasonic waves can be focused, reflected and refracted through a medium.

There appears to be a synergistic effect between the pharmacological activity of some drugs and ultrasound. Loverock et al. 1 have shown that 1 hr of exposure to ultrasound (2.6 MHz at 2.3 W/cm2) rendered Adriamycin significantly more toxic toward Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts. When the cell line was exposed to ultrasound alone, the cell viability was not affected. Using flow cytometry, the same study found an increase in concentration of the chemotherapeutic agent inside the cells.

Tachibana et al. 2 used a clonogenic assay to study the effect of 0.3 W/cm2 and 48 kHz ultrasound on the cytotoxicity of Cytosine Arabinoside (Ara-C). Sonicating human Leukemia cells for 120 seconds without Ara-C, did not cause a significant decrease in the number of colonies counted when compared to the control. When cells were sonicated for 60 seconds only in the presence of the chemotherapeutic agent, there was no significant difference in the cell survival rate between sonicated and non-sonicated cells. However, sonicating for 120 seconds in the presence of 1×10-7 M of Ara-C reduced the number of observed colonies 100 times when compared to cells incubated with the same concentration of the drug. This acoustic enhancement was more pronounced at the lower concentrations of Ara-C (2×10-9 to 2×10-8M) than at concentrations greater than 2×10-8 M.

This increase in cell death was not caused by hyperthermia, since the temperature increase was less than 0.2 °C throughout the experiments. In their attempt to understand the mechanism of this ultrasonic enhanced killing, the group used scanning electron microscopy and observed a decrease in the total number of microvilli and “a slight disrupted cell surface with flap-like wrinkles” under the action of ultrasound. They concluded that low intensity ultrasound altered the cell membrane, which resulted in the increase of Ara-C cell uptake.

Ultrasound has been shown to increase the killing of bacteria both in planktonic 3,4 and biofilm forms 5-7 in the presence of antibiotics. This bioacoustic effect was more pronounced at lower frequencies and decreased as the frequency of insonation increased 8,9. The effect was more pronounced in E. coli and P. aeruginosa (gram negative bacteria) than in S. epidermidis (gram positive bacteria). In vivo experiments confirmed the increased toxicity of gentamicin against E. coli biofilms in the presence of low frequency ultrasound (28.48 kHz and 0.3 W/cm2) 4,10. The group also found that this bioacoustic effect is operative with certain antibiotics, but is not manifest when others are used 11. They hypothesized that stable cavitation or sonoporation might be involved in increasing the transport of antibiotics into the bacteria either by reducing the mass transfer boundary layer around the cells, or by altering the cell membrane, thus allowing the antibiotics to diffuse through newly formed membrane pores.

Ultrasound enhances drug transport through tissues and across cell membranes. Several studies have shown that ultrasound facilitates drug delivery and absorption. Mitragotri et al. 12 have shown that low frequency ultrasound (20 kHz) can be used in the transdermal delivery of medium and high molecular weight proteins (including insulin, interferon, and erythropoietin). Three hours after the ultrasonic treatment concluded, the skin regained its transport resistance to insulin, indicating that no permanent damage was done by ultrasound. In another study by the same group, therapeutic ultrasound (1 MHz, 1.4 W/cm2, continuous) resulted in 14-fold elevation of cell membrane permeability for several chemical enhancers (e.g. poly(ethylene glycol), isopropyl myristate, 50% ethanol saturated with linoleic acid) 13.

Bommannan et al. 14,15 have shown that high frequency ultrasound (10 MHz and 16 MHz) for a period of 20 minutes increased the transport of salicylic acid by a factor of 4 (at 10 MHz) and 2.5 (at 16 MHz). Their studies also showed that lanthanum hydroxide penetrates human skin under the influence of ultrasound through the stratum corneum and the epidermal cell layers by an unknown intercellular mechanism.

Rapoport et al. 16 investigated the increase in intracellular drug uptake by HL-60 cells as a result of ultrasound irradiation (67 kHz and 2.5 W/cm2) using fluorescence techniques. The group found that that the amount of Dox (and its paramagnetic analog Ruboxyl) that intercalated DNA in leukemia cells increased as a result of sonication for an hour. In another related study, Munshi et al. 17 reported that the IC50 for Dox was reduced from 2.35 to 0.9 μg/ml when HL-60 were sonicated for one hour at 80 kHz in the presence of the anti-neoplastic agent. In that study, IC50 was defined as the concentration of (Dox) that resulted in 50% survival of the cells after 96 hours of post treatment incubation compared to the control.

Ultrasonic waves have been used to induce hyperthermia. Saad and Hahn 18 exposed Chinese hamster cells to 2.025 MHz ultrasound (average intensities range between 0.5 and 2 W/cm2) and to several drugs at temperatures ranging between 37°C and 43°C. The study showed that at lower intensities (0.5 W/cm2) the cytotoxicity of Adriamycin (synonymous with Doxorubicin) was significantly enhanced when the temperature was raised from 37°C to 41°C. At higher ultrasonic power densities (1 W/cm2), the cytotoxic effect of Adriamycin increased three fold when the temperature reached 41°C. The study concluded that the “temperature threshold” decreases as the power intensity of ultrasound increases.

Singer et al. 19 have also shown that hyperthermia induced by low-frequency ultrasound can decrease the number of Staphylococcus epidermidis colonies. In their experiments, 20-kHz ultrasound was applied for 5 seconds in a 10-second cycle (5:5 duty cycle) for 2 minutes. Two transducers were used: 1-cm cylindrical probe and 5-cm probe. There was a difference in the temperature ranges of both probes. The temperatures of the 1-cm probe ranged from 31 °C to 74 °C, while for the 5-cm probe the temperatures ranged between 22 °C and 40 °C. With the 5-cm probe, increasing the intensity of ultrasound caused bacterial counts to increase. However, when the 1-cm transducer was used, the number of colonies decreased as the intensity of ultrasound increased. The effect of ultrasound was more pronounced when the incubation fluid temperature exceeded 45 °C. The study stated that ultrasound has the ability to affect bacteria by three routes: thermal, cavitation and other “direct effects”. Since the bacterial counts were only affected when the temperature increased above 45-50 °C, the group attributed the antibacterial effect of low-frequency ultrasound to ultrasonic hyperthermic effects.

In summary, ultrasound can be used in combination with chemotherapy agents for several reasons. It has been shown to enhance the transport of drugs and other chemicals into cells and tissues. The cytotoxic efficiency of chemotherapeutic agents has been shown to increase under the action of ultrasound. Since ultrasound increases the local temperature of the exposed tissues, hyperthermia can be used as an additional ultrasonic advantage. Mechanisms are not well known, and there is a large effect of insonation frequency and power intensity that needs to be studied.

Polymeric micelles have been used to improve site-specific drug delivery in cancer therapy. The technique relies on these carriers' small size to extravasate at the tumor site where the drug can diffuse into the tumor and carry out its therapeutic effect 20-23. Although several groups have investigated the use of polymeric carriers to deliver chemotherapeutic and other drugs 24-42, the only two groups that have reported the use of polymeric micelles in conjunction with US are Rapoport, Pitt and colleagues at the University of Utah and Brigham Young University, and Myhr's group at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. The micelles used in both of these groups' studies are composed of polymers that belong to the Pluronic® family of block copolymers.

3. Pluronic® carriers

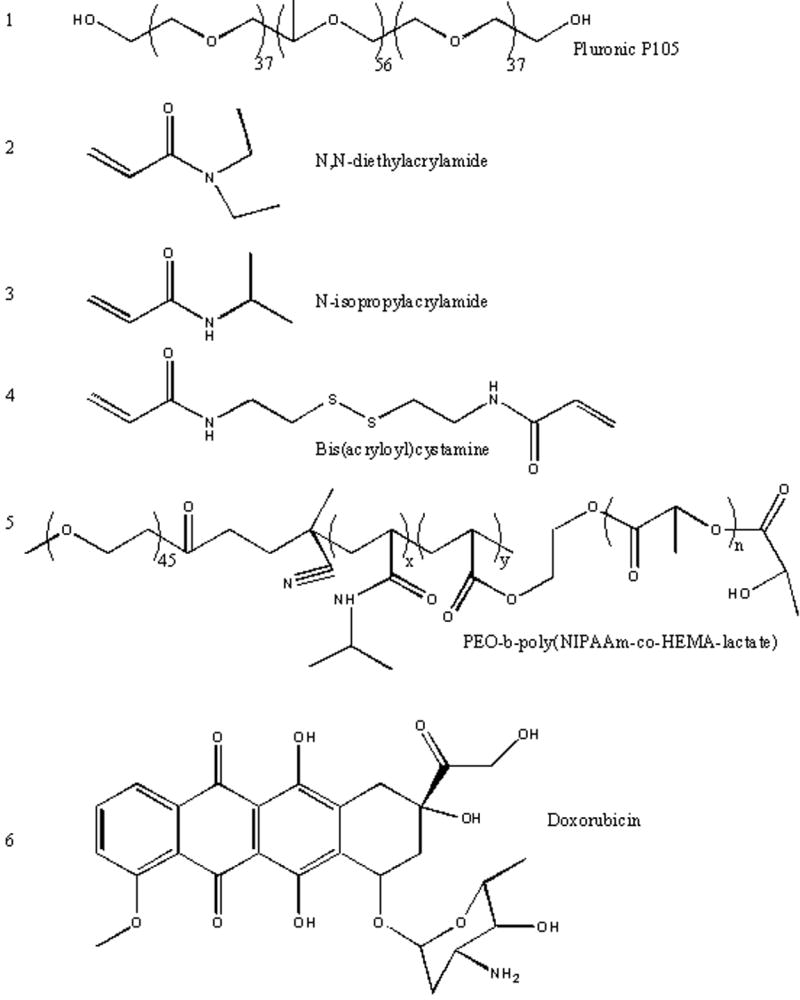

Pluronic® polymers are triblock copolymers of poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO) – poly (propylene oxide) (PPO) – poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO). They are soluble in water, and at sufficiently high concentrations they form micelles. For example, the critical micellar concentration of Pluronic® P-105 is approximately 1 wt% at room temperature.43 These micelles have a spherical, core-shell structure with the hydrophobic block forming the core of the micelle and the hydrophilic PEO chains forming the corona. Alexandridis et al. have studied Pluronic® properties in aqueous solutions 44-47. The phase state of Pluronic® micelles at a desired temperature can be controlled by choosing the Pluronic® with the appropriate molecular weight and PPO/PEO block length ratio, and by adjusting the solution concentration. The hydrodynamic radii of these micelles at physiological temperatures range between 5 and 20 nm, endowing them with the appropriate size to extravasate at the tumor site. Figure 1 shows the structures of Pluronic P105 and other compounds used in stabilizing polymeric micelles.

Figure 1.

Chemical Structure of Pluronic P105, PNHL, Doxorubicin and other compounds used in stabilizing polymeric micelles used in conjunction with ultrasonic drug delivery.

Kabanov et al. have studied the physical and biological properties of different Pluronic® compounds 48-61. The Pluronic® that was used most commonly in their studies was P105 16,17,62-72, which has an average molecular weight of 6500, the number of monomer units in PEO and PPO blocks being 37 and 56, respectively. An electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) study has shown that at room temperature and a concentration of 4 wt % or higher, P105 forms dense micelles with relatively little water in the core 73. That study also showed that depending on concentration, this copolymer associates as unimers, loose aggregates, and dense micelles. When associated as aggregates and micelles, chemotherapy drugs can accumulate in the hydrophobic PPO core while the PEO chains extend into the aqueous solution, thus preventing proteins from adsorbing on the surface of these drug carriers and identifying them to the reticulo-endothelial system.

In addition to the advantages of polymeric micelles, several studies have reported the effect of Pluronic® surfactants in overcoming multidrug resistance (MDR). Alakhov et al. 48 investigated the hypersensitization effect of Pluronic® P85 block copolymer on MDR human ovarian carcinoma cells. This study showed a substantial increase in the activity of Daunorubicin in the presence of 0.01 to 1 wt % copolymer. Venne et al. 51 have also shown that the use of Pluronic® micelles are effective in overcoming multi-drug resistance. That group studied the effect of Dox–(Figure 1) on MDR-hamster ovarian and breast cancer cells and observed a 290 and 700-fold increase respectively on the cytotoxic action of Dox in the presence of Pluronic® L61.

4. In vitro and in vivo examples

The feasibility of using ultrasound in association with polymeric micelles to deliver anti-neoplastic agents to cancer cell in vitro was first reported by Munshi et al. 17 They reported that a combination of US and Pluronic® P105-encapsulated Dox synergistically lowered the drug's IC50 from 2.35 to 0.19 μg/ml.

The same group then investigated the amount of DNA damage induced by Dox delivered to Human leukemia (HL-60) cells from Pluronic® P105 micelles with and without the application of US 65. Their results indicated that there was no significant DNA damage observed when the cells were exposed to 10 μg/ml of Dox in the presence of 10 wt % P105 for up to 9 hours of incubation. However, when US was applied, a rapid and significant increase in DNA damage and cell death was observed.

To understand the mechanism of this enhanced acoustic delivery, an ultrasonic exposure chamber with real-time fluorescence detection was used to measure acoustically-triggered Dox and Ruboxyl release from Pluronic® P105 micelles 69. The results showed that more drug was released at lower frequencies (20 kHz, 40 kHz, 70 kHz) and higher power densities, and that there was a power density threshold below which no release was observed74. The threshold apparently corresponded to the onset of collapse cavitation. The data was further corroborated by electron paramagnetic resonance using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as a radical trap 69. The ultrasonic intensity at onset of drug release coincided with the formation of DMPO-OH adducts formed upon the ultrasonication of a micellar solution containing 10 wt % P105. The OH radicals are generated as the temperature inside cavitating bubbles raises to several 1000 K. These radicals are then trapped using DMPO. Thus the collapse cavitation was implicated in this drug release phenomenon.

A subsequent study investigated the kinetics of ultrasonic drug delivery and reported that both release and re-encapsulation is completed within 0.6 seconds of initiation and cessation of ultrasound 66. Their report indicated that when insonation ceased, the chemotherapeutic agent is re-sequestered inside the micelle, thus potentially minimizing interaction with the aqueous surroundings, which may be beneficial to any non-targeted cells downstream of the ultrasonic focal volume. Several proposed physical models were analyzed mathematically to see which if any fit the observed kinetic data. The zero-order release with first order re-encapsulation appeared to represent this system better than the other proposed models 66.

Recently the kinetics of ultrasonic drug release from Pluronic® micelles were revisited 75. The observed triphasic nature of the release and the biphasic nature of re-encapsulation were represented by a more comprehensive mathematical model. This newer model assumed that micelles were of different sizes (five different sizes) and that the larger micelles were destroyed first, thus causing an initial fast release phase. Smaller micelles were then destroyed which caused a slower release phase. A third phase was also observed, and this was attributed to smaller fragments and smaller micelles coalescing into larger micelles. This new model, based upon experiments employing continuous US, was validated by its accurate prediction of drug release observed in a totally different data set in which pulsed US was used to release Dox from unstabilized Pluronic® P105 polymeric micelles 75.

Using fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry, Marin et al. 76 reported that exposure to ultrasound enhanced the intracellular uptake of Pluronic® micelles loaded with Dox and their internalization into the nucleus of HL-60 cells. Under exposure to US, more drug was present inside the cell in free form than was retained inside the micelles, which suggested that US had released the agent from the micelle core. They reported that US enhanced the intracellular uptake of the drug by HL-60 cells and attributed this increase to US-induced cellular change. Exposure to US has also been shown to change the intracellular distribution of the drug from acidic compartments (endosomes or lysosomes) to neutral compartments (in the cytoplasm and the nucleus) 71,77,78. The characteristic times of micellar drug release and cellular uptake were both on the order of 1-2 seconds, confirming the important role played by US in the transport of Dox into HL-60 cells 79.

The main challenge facing the use of micelles to deliver chemotherapy drugs is that the concentration of the polymer must be above the critical micellar concentration (CMC) to guarantee that the multimeric micellar structures remain intact and do not dissolve and release the drug before reaching the target site. An electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) study found that at low concentrations (less than 0.1 wt % P105), the polymer forms unimeric micellar structures at 37 °C; at intermediate concentrations, hydrophobic micellar cores are needed to effectively sequester hydrophobic chemotherapeutic agents. However, the body may not tolerate these required high concentrations of the surfactant. For this reason, a method for stabilizing the micelle and its hydrophobic core of was required.

Pruitt et al. stabilized Pluronic® micelles by polymerizing an interpenetrating network of N,N-diethylacrylamide (see Figure 1) within the hydrophobic core to form stabilized micelles called NanoDeliv™ 80. The size of these stabilized micelles ranges from 150 to 500 nm at 25°C and 50 to 400 nm at 37°C. The thermally responsive network expands at room temperature, allowing the drug to accumulate inside its hydrophobic core, and contracts above 31 °C, thus trapping the drug molecules when injected at body temperature. The polymerization employed bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC) as a crosslinker, and 2,2′-azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN) as an initiator. The hydrophobic NIPAAm monomers and crosslinkers polymerize inside the core of the P105 micelles, thus forming an interpenetrating network. Upon dilution, the network prevents the quick degradation of the micellar structure and keeps the therapeutic agent encapsulated, which in turn minimizes the drug's side effects. As the temperature surrounding the micelle increases, the association of water with the PEO blocks decreases (due to decreased hydrogen bonding), and the stabilized micelle shrinks, as evidenced by a decrease in its measured size80. The network-micellar structure is eventually degraded after several days (the in vitro half-life is approximately 17 hours 81). As with Pluronic® micelles, NanoDeliv™ micelles have been shown to release Dox upon exposure to US 82.

Recently, Zeng and Pitt 83 synthesized a new micellar vehicle using a block of polyethylene oxide, N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAAm), and polylactate ester of hydroxyl-ethyl methacrylate (pENHL) (see Figure 1). Due to the presence of the PEO block, this pENHL micelle retained its stealth characteristics, while the hydrophobic core provided a non-polar nano-environment where hydrophobic drugs can accumulate spontaneously. The main advantage of this carrier is the controlled degradability of the NIPAAm -HEMA-lactate block; thus its lifetime in the systemic circulation can be tailored by choosing the appropriate composition of NIPAAm, PEO and HEMA-lactate. This renders the synthesized polymer more versatile with respect to timed release and ultimate degradation in various applications. Like its predecessors, this pENHL micelle released Dox upon the application of 70 kHz ultrasound84.

Recently, in vivo studies examined the feasibility of acoustically activated drug delivery from the NanoDeliv™ carrier. Nelson et al. 85 showed that exposure to 20-kHz and 70-kHz US for 1 hour in the presence 2.67 mg/kg of Dox encapsulated in NanoDeliv™ significantly decreased (p=0.0061) the size of subcutaneous tumors in the hind leg of BDIX rats compared to control tumors on the contralateral leg. The Dox sequestered in NanoDeliv™ was administered systemically via tail vein injection, so both tumors were equivalently exposed to Dox, but only one tumor received US.

In similar experiments, Staples exposed the tumor to Dox in NanoDeliv™ to 20-kHz and 500-kHz US for 15 minutes 86. The insonated tumors grew more slowly than the contra lateral controls (p = 0.0047). Both frequencies were equally effective in treating the tumor.

Staples also investigated the distribution of Dox in several organs at various times after the Dox/ NanoDeliv™ injection and insonation87. He found that both the insonated and control tumors had Dox concentrations that were not statistically different 6 or more hours following drug injection (p = 0.988). However, at the 30 minute time point, the concentration of Dox in the insonated tumor was higher (p = 0.055). The tumors receiving Dox and NanoDeliv™ with insonation grew more slowly (p = 0.0047). Dox concentrations found in the heart, kidneys, liver, and muscle decreased to undetectable levels within a week, but a slightly measurable amount persisted in the tumors beyond 1 week.

Gao et al. 88 studied the intracellular distribution in mice of fluorescently labeled unstabilized Pluronic® P105 and Pluronic® P105 stabilized using PEG-diacylphospholipid. The study showed that 1 MHz insonation for times as short as 30 s were able to enhance the accumulation of these labeled micelles at the tumor site in ovarian cancer-bearing nu-nu mice. Employing flow cytometry to the tumor tissues excised from inoculated mice, Rapoport et al. 89 showed that micelle accumulation was significantly higher in the ultrasonicated tumor than in the non-insonated tumor of the same mouse. The study also reported that encapsulated Dox did not accumulate in the heart, which would ameliorate the well-documented cardiotoxicity of this anti-neoplastic agent. Although low frequency US (20 to 100 kHz) 66,69 was able to release more Dox from Pluronic® micelles than high frequency US (1 MHz and 3 MHz) 70, Rapoport's in vivo research efforts used 1 MHz US because it can be focused more precisely on the tumor site and causes less sonolysis.

Recently, Myhr et al. have shown that a combination of NanoDeliv™-encapsulated fluorouracil (5-FU) combined with ultrasound significantly reduced the tumor (human colon cancer) volume in Balb/c nude mice, when compared to the control group (p = 0.0034). The authors reported a more significant tumor volume reduction at higher drug concentrations.

5. Mechanisms

The mechanisms of this acoustically activated micellar drug delivery system are still under investigation, and in vitro there is a strong correlation with insonation frequency and power density that suggests a strong role of cavitation. Here we will discuss the two main mechanisms that render this micellar drug delivery system effective. Ultrasound appears to disrupt the core of polymeric micelles, allowing the drug to be released in the volume of the ultrasonic field. Additionally, ultrasonic waves have been shown to cause the formation of micropores in cell membranes, which in turn allows for the passive diffusion of drugs into cell.

5.1 Disruption of micelles

After proving that Dox and Rb were released from micelles under the action of ultrasound 69, Husseini et al. embarked on a study of the mechanism underlying this release. They improved their previously designed ultrasonic exposure chamber with fluorescence detection 66,69, so as to record acoustic emissions at 70 kHz while simultaneously recording the decrease in fluorescence. This in vitro study showed that there is a threshold value of about 0.38 W/cm2 below which no measurable release occurred. Furthermore the onset of Dox release from P105 micelles corresponded to the emergence of a subharmonic peak in acoustic spectra at this same threshold. The existence of a threshold at this intensity tends to point toward a strong role of cavitation, particularly inertial or collapse cavitation, in this release phenomenon. Several groups have reported the existence of a threshold for the onset of inertial cavitation 90-94. Daniels et al. reported an inertial cavitation threshold between 0.036 to 0.141 W/cm2 at 750 kHz insonation 90, while Hill showed the thresholds to occur below 1 W/cm2 for frequencies ranging between 0.25 and 4 MHz 91. Obviously there is a wide range of intensities reported for the onset of inertial cavitation. We attribute this to two factors. First, the threshold should in general decrease as the frequency decreases. But this does not explain all of the variation in reported thresholds. We attribute a good deal of the remaining variation to the various experimental conditions under which the thresholds were measured. For example, the thresholds will be sensitive to the state of degassing of the liquid employed, to the temperature of the experiment, to the presence of surfactants or other substances that can serve as a nidus for heterogeneous bubble nucleation, and to the equipment and analytical procedures employed to detect the cavitation events. To date there is no standard method for the measurement of thresholds.

Several publications have reported ultrasonic intensity thresholds for an observed biological effect in cells and tissues 91,95-104. Mitrogotri et al. were the first to show the existence of an ultrasonic threshold for enhancing skin permeability 99,103,105-107. This threshold is a strong function of ultrasound frequency; as the frequency increases so does the threshold. Tang el al. 108 showed that low-frequency sonophoresis (LFS) was able to permeabilize pig skin using 20 kHz ultrasound. They postulated that the key mechanism involved in LFS is cavitation bubbles induced by US. Copious research has been conducted on increased cell membrane permeability under the action of ultrasound 95,96,104,109,110. For example, there is a reported threshold for DNA delivery to rabbit endothelial cells of about 2,000 W/cm2 at a pulse average intensity 0.85 MHz (short pulse average intensity) 96. Another example is the threshold of 0.06 W/cm2 at 20 kHz reported by Rapoport et al. for HL-60 lysis 89. The range reported for biological thresholds is obviously very large, and thus provides little guidance for a priori prediction of threshold values for biological events. One must remember that in biological systems, the observed event is not the threshold of inertial cavitation; there is usually an ultrasonic intensity beyond the simple inertial cavitation threshold that is required to provide sufficient numbers and sufficient intensities of damaging cavitation events. Biological systems are much more complicated. In addition to the experimental factors mentioned above (e.g., level of gas saturation and heterogeneous nucleation materials), one must also consider the cells involved. For example, biological manifestations will be related to things such as the proximity of the cells to the collapse events, the presence of microjets from collapse events, the cell membrane strength and integrity, the requirements following cell membrane permeation (transport only to the cytosol or all the way to the nucleus) to produce a biological response, and much more. Obviously, much research remains to be done in this area of predicting thresholds for cellular response.

In this review, we will devote some discussion to the origin of the subharmonic acoustic peak, inertial cavitation, and its relation to the release phenomena. As bubbles oscillate with increasing amplitude in an ultrasonic field (of frequency f), they start to generate higher harmonic (2f, 3f, etc.), ultraharmonic (3/2 f, 5/2f, etc.), and subharmonic (f/2, f/3, etc.) emissions. There are reports that correlate the subharmonic emission with certain indicators of inertial cavitation, including sonoluminescence, acoustic white noise, and iodine generation 91,111-113. Leighton used mathematical modeling of cavitating bubbles to simulate a signal at f/2 (the subharmonic) and came to the conclusion that a subharmonic occurs due to a prolonged expansion phase immediately preceding a delayed collapse phase of the bubble implosion event 114. However, modeling by others show that the f/2 signal can be produced (mathematically at least) without collapse cavitation occurring 92,115-117, albeit the definition of “collapse” is difficult to define in a mathematical model 118.

Sundaram et al. 105 clearly show that the membrane permeability of 3T3 mouse cells correlates with an increase in background noise in acoustic spectra. The group came to the conclusion that ultrasound-induced permeabilization of cell membranes is caused by collapse cavitation events. On the other hand, Liu et al. found a strong dependence of the degree of hemolysis (permeabilization of red blood cells as measured by the degree of hemoglobin release) on the intensities of the subharmonic and ultraharmonic frequencies, but not on the broadband noise 109. The group concluded that the best correlation between ultrasonic parameters and hemolysis was the product of the total ultrasonic exposure time and the subharmonic pressure. Accordingly, there are varied opinions as to whether the subharmonic emission always correlates with biological phenomena, or even with collapse cavitation.

As to the relationship between the mechanism of release and inertial cavitation, Husseini et al. postulated that as the shock wave caused by collapse cavitation propagates through the vicinity of a micelle, the abrupt compression and expansion of fluid in the shock wave is able to shear open the micelle so that the drug is released or at least exposed to the aqueous environment. Oscillating bubbles, even in stable cavitation, create very strong shear forces near the surface of the bubble. The shearing velocity of fluid near a 10 micron (diameter) bubble, with a 1 micron oscillation amplitude and 70 kHz oscillation frequency is approximately 1 m/s 119. Additionally, it important to keep in mind that the extremely high viscous shear rates near the surface of 10-μm bubbles are on the order of 105 sec-1. Furthermore, this rate is equivalent to shearing water in a 1 mm gap between parallel plates in which plate is stationary and the other moving at 100 m/s. Thus, the group speculated that these shear forces may be strong enough to open up a P105 micelle, exposing the hydrophobic drug inside its core to the surrounding aqueous environment.

The group also extended their study of the release mechanism to stabilized and unstabilized micelles 84. In this study they compared the release of Dox from the core of unstabilized Pluronic® 105 micelles to the release from stabilized micelles such as NanoDeliv™ micelles and micelles of pENHL described previously in section 3. They found that the release of Dox at 37 °C from Pluronic® micelles appeared to be several times higher than the release from the more stabilized micelles. Interestingly, the onset of release occurred at about the same power density for all carriers investigated in their study, whether stabilized or not. Similarly, the threshold of Dox release from all three micelles correlated with the emergence of subharmonic peaks in the acoustic spectra.

Apparently the structures of the stabilized and non-stabilized micelles are perturbed by cavitation events that cause the release of Dox. The group hypothesized that stabilized micelles are less susceptible to disruption by the shearing forces of shock waves produced by cavitation events 84. Since the threshold of release also correlates with the subharmonic peak in all micellar systems investigated, discovering the origin of the subharmonic peak is vital in understanding drug release from micelles under the action of ultrasound.

5.2 Disruption of cell membrane

Although Pitt's group has focused on studying the possible mechanisms by which the P105 micelles and ultrasound drug delivery system induce drug uptake by the cancer cells, is has also studied the biological mechanism involved here. The comet assay was used to quantify the amount of DNA damage in HL-60 cells by measuring the fraction and length of broken nuclear DNA strands 120-122. Large amounts of DNA damage as measured by the comet assay is indicative of cell death, either by necrosis or by apoptosis 123,124. Results of the comet assay show that Dox eventually binds to the DNA and causes it to fragment 65. In a separate but related study, Husseini et al. 65,125 reported on the mode of cell death exhibited by cells exposed to a combination of Pluronic® micelles, ultrasound and Dox. Using the comet assay, the group observed the electrophoretic pattern of the nuclear DNA from HL-60 cells insonated at 70 kHz in a solution of P105 micelles containing 10 μg/ml Dox for 30 minutes, 1 hour and 2 hours. The pattern of the DNA fragments as well as the gradual damage observed after two hours of ultrasonic exposure were consistent with apoptosis as a mode of cell death rather than necrosis. However, the question remains as to if and how ultrasound enhances uptake of Dox by the cell. In this section, we will discuss three postulated mechanisms that have been tested in an attempt to answer the above question. These mechanisms are 1) ultrasonic release of the drug from micelles is followed by normal transport into the cell; 2) ultrasound upregulates endocytosis of the micelles (with drug) into the cell; 3) ultrasound perturbs the cell membrane which increases passive transport of the drug and Pluronic® molecules into the cell.

The first hypothesis proposes that the drug is released from micelles outside the cancer cells, followed by normal penetration of the polymer and drug into the cells by simple diffusion or normal cellular uptake mechanisms. To test this postulated mechanism, the hydroxyl groups at the ends of P105 chains were labeled with a fluorescein derivative 70,71,126. HL-60 cells were then incubated or sonicated with the fluorescein-labeled P105 micelles containing Dox, which fluoresces at a different wavelength. Results showed that Dox in 10 wt % P105 appeared inside the cells.

The next question was whether the fluorescently-labeled P105 entered the cells along with or independent of the Dox. The experiments revealed the presence of P105 inside the cells when incubated or insonated for 20 minutes. Because the labeled P105 molecules themselves were found inside the HL-60 cells, they rejected the first hypothesis of external drug release followed by passive drug diffusion without the polymeric diffusion into the cells. Although their experiment showed that the P105 entered the cells, it was not possible to determine whether the copolymer entered the cells through holes punched in the cell membrane or through endo-/pino-cytotic routes.

Next they turned their attention to the second hypothesis whereby entire micelles (with drug) are endocytosed into the cells. Since it is unlikely that HL-60 cells express a receptor for Pluronic® micelles, receptor-induced endocytosis was considered to be very unlikely. However, pinocytosis involves vesicles that nonspecifically engulf small volumes of extracellular fluid and any material contained therein. To test the postulate that the cells were taking up the drug and P105 in by endocytosis, a model drug that fluoresces more strongly in acidic environments was used, namely Lysosensor Green. This probe has a pKa of 5.2, which causes it to fluoresce more strongly in an acidic compartment such as a lysosome 126. The great majority of endosomes fuse with a primary lysosome to form a secondary lysosome, which has a pH of about 4.8 while the pH outside these compartments is about 7.1. Cells exposed to US and P105 micelles with Lysosensor Green were examined by flow cytometry, which showed no difference in fluorescence between cells incubated and insonated for 1 hour at 70 kHz. Thus, ultrasonic exposure did not cause the probe to partition to a more acidic environment anymore than it did without ultrasound, and the hypothesis was rejected that US induces upregulation of endo-/pino-cytosis. The observation that US enhanced the uptake of both drug and labeled Pluronic® supported the third hypothesis that drug-laden micelles entered through holes in the membranes of insonated cells in these studies.

It is relevant that Rapoport et al. 77 reported that US-assisted micellar drug delivery enhances the rate of endocytosis into cells. Furthermore, Sheikov et al. showed that US induced pinocytosis in the endothelial cells lining arterioles and capillaries of the brain 127. Thus the role of US in promoting endocytosis and pinocytosis is unresolved. It may be that different cells respond differently to ultrasonic exposure such that a general and simplified rule cannot be applied.

The ability of carefully controlled US to create non-lethal and repairable holes in cell membranes is gaining support. For example, Schlicher et al. have shown that the accumulation of the model drug calcein in prostate cancer cells was caused by US-induced membrane disruptions 128.

In a similar study of US-induced calcein uptake into colon cancer cells, Stringham et al. proved the involvement of collapse cavitation in cell membrane disruption. The calcein uptake was suppressed by increasing the hydrostatic pressure at constant ultrasonic intensity at 500 kHz. It is well known that increasing hydrostatic pressure suppresses collapse cavitation, although stable cavitation still occurs. In these experiments lower membrane permeability correlated directly with higher hydrostatic pressure 129.

Tachibana et al. has reported the increase in cell membrane permeability and skin porosity caused by ultrasound 2,130-135. His group has shown that the exposure of HL-60 cells to 255 kHz of ultrasound and MC 540 (an anticancer drug) for 30 seconds formed pores in the cell membrane 2. The cytoplasm of some cells seemed to have extruded through the pores formed in the cell membrane as a result of sonoporation. When cells were exposed to ultrasound alone, the cell membrane showed only minor disruptions. Saito et al. 136 demonstrated that exposure to ultrasound increased the permeability of corneal endothelium cells. The increase in permeability appeared to be reversible and the cells regained their membrane integrity after several minutes. Thus there is ample evidence that ultrasonic cavitation events create transient holes in the cell membrane, which in the case of micellar drug delivery would increase the passive diffusion of micelles and drugs into the cells.

6. Future

6.1 Remaining questions on mechanism

Before examining the remaining questions on the mechanism of acoustically activated micellar drug delivery, we need to review the origin and characteristics of the two modes of cavitation as they affect biological tissues.

This discussion leads us to the main mechanistic question remaining: Which type of cavitation is mainly involved in acoustically activated drug delivery from micelles?

Future studies should focus on distinguishing between these two mechanisms. This may be accomplished by listening to acoustic emissions or by measuring the sonoluminescence emitted during insonation, keeping in mind that stable cavitation produces no broadband acoustic emission and generates little if any luminescent emissions. Another characteristic that can be employed to distinguish between the two modes of cavitation is the measurement of free radicals that are produced by the high temperatures of bubble collapse.

Another interesting technique that has not been fully utilized in micellar drug delivery is mathematical modeling of bubble behavior and non-equilibrium thermodynamics. These techniques might help in resolving the questions surrounding the role of cavitation in micellar drug delivery. To achieve this goal a better understanding of bubble dynamics, the physics of microbubble oscillation and collapse, the parameters controlling microbubble size, the internal gas composition, as well as acoustic frequency and pressure amplitude are needed prior to initiating the model.

6.2 Therapeutics

The agents that have been encapsulated in nanoparticles for ultrasonic delivery have been primarily hydrophobic drugs. Future work should include other drug delivery vehicles, such as liposomes, which have hydrophilic volumes and are able to sequester and deliver hydrophilic drugs, DNA or RNA.

6.3 Other targeting techniques

The micellar drug delivery system developed by Pitt et al. shows strong promise. First, it is able to effectively sequester a potent chemotherapeutic agent inside the core of stabilized micelles and successfully release Dox upon application of US. They also reported success in using a second generation of nanocapsules in vivo using a rat model of colorectal cancer. Although this novel drug delivery system is an excellent start, it most probably can be improved.

One way of improving this micellar delivery system is to decorate the surface with a targeting moiety, thus creating a double targeting system. There are many reports of the attachment of antibodies to solid particles and gas bubbles137,138. Often this is done by covalent attachment via the available –SH groups in Fab fragments of specific antibodies 139. Other techniques employ attachment of short peptide sequences (e.g. RGD140,141) or larger biomolecules (e.g. folic acid and biotin 141,142).

Folic acid derivatives (folated molecules) have been shown to be endocytosed into human cancerous cells via pinocytosis. Various cancer cells over-express the folate receptor on their surface 143,144. Thus, the conjugation of folate molecules to drug delivery carriers gained special attention in recent years since it minimizes the interaction between healthy cells and chemotherapeutic agents which will in turn reduce the side effects of conventional chemotherapy. Folate molecules display a high affinity for the folate receptor which facilitates the binding of the folated-drug to the its receptor 145-147. This leads to the internalization of the drug carrier by the cell. A folate-poly(ethylene glycol)- Pt(II) conjugate has been synthesized by Steenis et al. 148, while two other groups succeeded in synthesizing other folate-drug conjugates 149,150. More recently, the attachment of the folate molecule to micellar structures has been reported 29,151-153. The aim of conjugating the folate onto micelles is to reduce the amount of the drug in the systemic circulation until the drug loaded micelle is taken up by the cancerous target cell via endocytosis.

There are several aspects that still need to be explored in order to understand the role of ultrasound in acoustically activated drug delivery from micelles: the role of ultrasonic-induced cavitation in releasing drug from the micellar carrier, the use of ultrasound to specifically target drug release to a specific tissue without releasing drug in non-targeted tissues, and the ability of ultrasound to cause cells to take up the drug.

One of the most important aspects that need to be explored is the role of the nature of the carrier in ultrasonic-activated tumor regression. To answer this question, several different carriers should be examined for their efficiency in delivering chemotherapeutic agents to diseased tissues. These include micelles, liposomes, and other targeted vesicles. Additionally, the concentration of the therapeutic agent in the tumor should be investigated as a function of the carrier when ultrasound is applied.

Most importantly, the aspect that warrants the most attention in the future of micellar drug delivery by US is the optimization of acoustic parameters. This includes elucidating the effect of frequency and the total energy delivered upon drug release and cellular penetration/retention. Additionally, the length of insonation time and the intervals between acoustic treatments should be optimized to maximize drug efficiency.

7. Summary

This article has reviewed the recent advances in the use of ultrasound and polymeric micelles in cancer therapy. This area of drug delivery is anticipated to experience considerable technological growth in the next ten years for many reasons. Ultrasound is an extremely useful modality in drug delivery because of its non-invasive nature and the ease with which ultrasonic waves can be controlled. Additionally, high frequency ultrasound can be used both as a diagnostic technique and as a delivery mechanism. Stabilized polymeric micelles have been synthesized to increase the vehicle's circulation time, its loading capacity and the hydrophobicity of its core in order to meet the needs of the particular delivery system being investigated.

Thus, the combination of micelles and ultrasound has a strong potential for the future of drug delivery in the treatment of malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (CA 98138) which supported portions of this research.

References

- 1.Loverock P, Ter Haar G, Ormerod MG, Imrie PR. The effect of ultrasound on the cytoxicity of adriamycin. Brit J Radiol. 1990;63:542–546. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-63-751-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tachibana K, Uchida T, Tamura K, Eguchi H, Yamashita N, Ogawa K. Enhanced cytotoxic effect of Ara-C by low intensity ultrasound to HL-60 cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;149:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rediske AM, Hymas WC, Wilkinson R, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic enhancement of antibiotic action on several species of bacteria. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1998;44:283–288. doi: 10.2323/jgam.44.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rediske AM, Rapoport N, Pitt WG. Reducing bacterial resistance to antibiotics with ultrasound. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1999;28(1):81–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian Z. Antibiotic and Ultrasonic Treatment of Bacterial Biofilm. Brigham Young University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian Z, Sagers RD, Pitt WG. The role of insonation intensity in acoustic-enhanced antibiotic treatment of bacterial biofilms. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 1997;9:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian Z, Sagers RD, Pitt WG. Investigation of the mechanism of the bioacoustic effect. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44:198–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<198::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian Z, Sagers RD, Pitt WG. The Effect of Ultrasonic Frequency upon Enhanced Killing of P. aeruginosa Biofilms. Annals Biomed Eng. 1997;25(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02738539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LL, Peterson RV, Pitt WG. Treatment of bacterial biofilms on polymeric implants using antibiotics and ultrasound. J Biomat Sci Polymer Ed. 1998;9:1177–1185. doi: 10.1163/156856298x00712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rediske AM, Roeder BL, Brown MK, Nelson JL, Robison RL, Draper DO, Schaalje GB, Robison RA, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic enhancement of antibiotic action on Escherichia coli biofilms: an in vivo model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(5):1211–1214. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rediske AM, Roeder BL, Nelson JL, Robison RL, Schaalje GB, Robison RA, Pitt WG. Pulsed ultrasound enhances the killing of E. coli biofilms by aminoglycoside antibiotics in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:771–772. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.771-772.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitragotri S, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Ultrasound-Mediated Transdermal Protein Delivery. Science. 1995;269:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.7638603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson ME, Mitragotri S, Patel A, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Synergistic Effects of Chemical Enhancers and Therapeutic Ultrasound on Transdermal Drug Delivery. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1996;85(7):670–677. doi: 10.1021/js960079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bommannan D, Okuyama H, Stauffer P, Guy RH. Sonophoresis. I. The Use of High-Frequency Ultrasound to Enhance Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharm Res. 1992;9(4):559–564. doi: 10.1023/a:1015808917491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bommannan D, Menon GK, Okuyama H, Elias PM, Guy RH. Sonophoresis. II. Examination of the Mechanism(s) of Ultrasound-Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharm Res. 1992;9(8):1043–1047. doi: 10.1023/a:1015806528336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapoport NY, Herron JN, Pitt WG, Pitina L. Micellar delivery of doxorubicin and its paramagnetic analog, ruboxyl, to HL-60 cells: effect of micelle structure and ultrasound on the intracellular drug uptake. J Controlled Rel. 1999;58(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(98)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munshi N, Rapoport N, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic activated drug delivery from Pluronic P-105 micelles. Cancer Letters. 1997;117:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saad AH, Hahn GM. Ultrasound Enhanced Drug Toxicity on Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in Vitro. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5931–5934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer AJ, Coby CT, Singer AH, T HC, Jr, Tortora GT. The Effects of Low-Frequency Ultrasound on Staphylococcus epidermidis. Current Microbiology. 1999;38:194–196. doi: 10.1007/pl00006786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Fukushima S, Okamoto K, Kataoka k. Selevtive Delivery of Adriamycin to solid tumor using a polymeric micelle carrier system. Journal of drug targeting. 1999;7(3):171–186. doi: 10.3109/10611869909085500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon G, Naito M, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: loading and release of doxorubicin. J Control Release. 1997;48:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon GS, Naito M, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. Physical entrapment of Adriamicin in AB block copolymer micelles. Pharm Res. 1995;12:192–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1016266523505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon GS, Kataoka K. Block copolymer micelles as long circulating drug vehicles. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1995;16:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutowska A, Bae YH, Jacobs H, Feijen J, Kim SW. Thermosensitive Interpenetrating Polytmer Networks: Synthesis, Characterization, and Macromolecular Release. Macromolecules. 1994;27:4167–4175. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vernon B, Gutowska A, Kim SW, Bae YH. Thermally Reversible Polymer Gels for Biohybrid Artificial Pancreas. Macromol Symp. 1996;109:155–167. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong B, Bae YH, Lee DS, Kim SW. Biodegradable Block Copolymers as Injectable Drug-Delivery Systems. Nature. 1997;388:860–862. doi: 10.1038/42218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong B, Bae YH, Kim SW. Drug release from biodegradable injectable thermosensitive hydrogel of PEG-PLGA-PEG triblock copolymers. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;63:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao ZG, Lee DH, Kim DI, Bae YH. Doxorubicin loaded pH-sensitive micelle targeting acidic extracellular pH of human ovarian A2780 tumor in mice. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2005;13(7):391–397. doi: 10.1080/10611860500376741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee ES, Na K, Bae YH. Polymeric micelles for tumor pH and folate mediated targeting. J Controlled Release. 2003;91:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae Y, Jang WD, Nishiyama N, Fukushima S, Kataoka K. Multifunctional polymeric micelles with folate-mediated cancer cell targeting and pH-triggered drug releasing properties for active intracellular drug delivery. Molecular Biosystems. 2005;1(3):242–250. doi: 10.1039/b500266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee ES, Na K, Bae YH. Doxorubicin loaded pH-sensitive polymeric micelles for reversal of resistant MCF-7 tumor. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;103(2):405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae Y, TA TAD, Zhao A, Kwon GS. Mixed polymeric micelles for combination cancer chemotherapy through the concurrent delivery of multiple chemotherapeutic agents. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;122(3):324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bae Y, Buresh RA, Williamson TP, THH THHC, Furgeson DY. Intelligent biosynthetic nanobiomaterials for hyperthermic combination chemotherapy and thermal drug targeting of HSP90 inhibitor geldanamycin. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;122(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leroux JC. Injectable nanocarriers for biodetoxification. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2(11):679–684. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Garrec D, Ranger M, Leroux JC. Micelles in Anticancer Drug Delivery. Am J Drug Deliv. 2004;2(1):15–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leroux JC. Injectable nanocarriers for biodetoxification. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2(11):679–684. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi J, Giasson S, Khalid MN, Delmas P, Allen C, Leroux JC. Long-circulating poly(ethylene glycol)-coated emulsions to target solid tumors. European Journal Of Pharmaceutics And Biopharmaceutics. 2007;67(2):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torchilin VP. Lipid-Core Micelles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Curr Drug Delivery. 2005;2:319–327. doi: 10.2174/156720105774370221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukyanov AN, Elbayoumi TA, Chakilam AR, Torchilin VP. Tumor-targeted liposomes: doxorubicin-loaded long-circulating liposomes modified with anti-cancer antibody. Journal of Controlled Release. 2004;100(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kale AA, Torchilin VP. “Smart” drug carriers: PEGylated TATp-Modified pH-Sensitive Liposomes. Journal Of Liposome Research. 2007;17(34):197–203. doi: 10.1080/08982100701525035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Enhanced cytotoxicity of monoclonal anticancer antibody 2C5-modified doxorubicin-loaded PEGylated liposomes against various tumor cell lines. European Journal Of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;32(3):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2007.05.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torchilin VP. Nanocarriers. Pharmaceutical Research. 2007;24(12):2333–2334. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rapoport NY, Christensen DA, Fain HD, Barrows L, Gao Z. Ultrasound-triggered drug targeting of tumors in vitro and in vivo. Ultrasonics. 2004;42(19):943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2004.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexandridis P, Holzwarth JF, Hatton TA. Micellization of Poly(ethylene oxide)- Poly(propylene oxide)- Poly(ethylene oxide) Triblock Copolymer in Aqueous Solutions: Thermodynamics of Copolymer Association. Macromolecules. 1994;27(9):2414–2425. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexandridis P, Nivaggioli T, Hatton TA. Temperature Effects on Structural Properties of Pluronic P104 and F108 PEO-PPO-PEO Block Copolymer Solutions. Langmuir. 1995;11:1468–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexandridis P, Athanassiou V, Hatton TA. Pluronic-P105 PEO-PPO-PEO Block Copolymer in Aqueous Urea Solutions: Micelle Formation, Structure, and Microenvironment. Langmuir. 1995;11:2442–2450. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alexandridis P, Hatton TA. Poly(ethyleneoxide)-poly(propyleneoxide)-Poly(ethyleneoxide) block copolymer surfactants in aqueous solutions and at interfaces: thermodynamics, structure, dynamics, and modeling. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 1995;96:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alakhov VY, Moskaleva EY, Batrakova E, Kabanov AV. Hypersensitization of Multidrug resistant Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells by Pluronic P85 Block Copolymer. Bioconj Chem. 1996;7:209–216. doi: 10.1021/bc950093n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabanov AV, Nazarova IR, Astafieva IV, Batrakova EV, Alakhov VY, Yaroslavov AA, Kabanov VA. Micelle formation and solubilization of fluorescent probes in poly(oxyethylene-b-oxypropylene-b-oxyethylene) solutions. Macromolecules. 1995;28:2303–2314. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV, Melik-Nubarov NS, Fedoseev NA, Dorodnich TY, Alakhov VY, Nazarova IR, Kabanov VA. A new class of drug carriers: micelles of poly(oxyethylene)-poly(oxypropylene) block copolymers as microcontainers for targeting drugs from blood to brain. J Controlled Release. 1992;22:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venne A, Li S, Mandeville R, Kabanov A, Alakhov V. Hypersensitizing Effect of Pluronic L61 on Cytotoxic Activity, Transport, and Subcellular Distribution of Doxorubicin in Multiple Drug-resistant Cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3626–3629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batrakova EV, Dorodnych TY, Klinskil EY, Kliushnenkova EN, Shemchukova OB, Goncharova ON, Arjakov SA, Alakov VY, Kabanov AV. Anthracycline Antibiotics Non-Covalently Incorporated into the Block Copolymer Micelles: In Vivo Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Activity. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1545–1552. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller DW, Batrakova EV, Waltner TO, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV. Interaction of Pluronic Block Copolymer with Brain Microvessel Endothelial cells: Evidence of Two Potential Pathways for drug Absorption. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1997;8(5):649–657. doi: 10.1021/bc970118d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabanov AV, Chekhonin VP, Alakhov VYu, Batrakova EV, Lebedev AS, Melik-Nubarov NS, Arzhakov, Kabanov VA. The neuroleptic activity of haloperidol increases after its solubilization in surfactant micelles. Micelles as microcontainers for drug targeting. FEBS lett. 1989;258:343–345. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kabanov AV, Nametkin SN, Klyachko NL, Levashov AV. The principal difference in regulation of the catalytic activity of water soluble and membrane forms of enzymes in reversed micelles. γ-Glutamyltransferase and aminopeptidase. FEBS Lett. 1990;267:236–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80933-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kozlov MY, Melik-Nubarov NS, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Relationship between Pluronic Bock Copolymer Structure, Critical Micellization Concentration and Partitioning Coefficients of Low Molecular Mass Solutes. Macromolecules. 2000;33:3305–3313. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Batrakova E, Lee S, Li S, Venne A, Alakhov V, Kabanov A. Fundamental Relationships between the Composition of Pluronic Block Copolymers and their Hypersensitization Effect in MDR Cancer Cells. Pharm Res. 1999;16(9):1373–1379. doi: 10.1023/a:1018942823676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kozlov MY, Melik-Nubarov NS, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Relationship between Pluronic Block Copolymer Structure, Critical Micellization Concentration and Partitioning Coefficients of Low Molecular Mass Solutes. Macromolecules. 2000;33:3305–3313. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kabanov AV, Alakhov VY. Pluronic Block Copolymers in Drug Delivery: from Micellar Nanocontainers to Biological Response Modifiers. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 2002;19(1):1–73. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v19.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Batrakova EV, Li S, Li Y, Alakhov VY, Elmquist WF, Kabanov AV. Distribution kinetics of a micelle-forming block copolymer Pluronic P85. J Control Release. 2004;100(3):389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Batrakova E, Li S, Li Y, Alkhov VY, Elmquist W, Kabanov AV. Distribution kinetics of micelle-forming bock copolymer pluronic 185. J Control Release. 2004;100:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rapoport N, Munshi N, Pitt WG. 3rd International Symposium on Polymer Therapeutics; London. 1998. p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rapoport N, Munshi N, Pitina L, Pitt WG. Pluronic Micelles as Vehicles for Tumor-Specific Delivery of Two Anti-Cancer Drugs to HL-60 Cells Using Acoustic Activation. Polymer Preprints. 1997;38(2):620–621. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rapoport N, Pitina L, Munshi N, Pitt WG. 8th International Symposium on Recent Advances in Drug Delivery Systems; Salt Lake City, Utah. 1997. pp. 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Husseini GA, El-Fayoumi RI, O'Neill KL, Rapoport NY, Pitt WG. DNA damage induced by micellar-delivered doxorubicin and ultrasound: comet assay study. Cancer Letters. 2000;154:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Husseini GA, Rapoport NY, Christensen DA, Pruitt JD, Pitt WG. Kinetics of ultrasonic release of doxorubicin from Pluronic P105 micelles. Coll Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2002;24:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Husseini G, Christensen DA, Pitt WG, Rapoport N. Twenty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the Society For Biomaterials; Providance, Rhode Island, USA. April 28-May2, 1999; 1999. p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Husseini GA, Pitt WG, Fayoumi RYA, O'Neill KL, Rapoport NY. AICHE 1999 Annual Meeting; Dallas, Texas, USA. October 31-November 5, 1999; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Husseini GA, Myrup GD, Pitt WG, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY. Factors Affecting Acoustically-Triggered Release of Drugs from Polymeric Micelles. J Controlled Release. 2000;69:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marin A, Sun H, Husseini GA, Pitt WG, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY. Drug delivery in pluronic micelles: effect of high-frequency ultrasound on drug release from micelles and intracellular uptake. J Controlled Rel. 2002;84(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muniruzzaman MD, Marin A, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Pitt WG, Husseini G, Rapoport NY. Intracellular uptake of Pluronic copolymer: effects of the aggregation state. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2002;25(3):233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rapoport N, Pitt WG, Sun H, Nelson JL. Drug delivery in polymeric micelles: from in vitro to in vivo. J Control Rel. 2003;91(12):85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rapoport N, Caldwell K. Structural transitions in micellar solutions of Pluronic P-105 and their effect on the conformation of dissolved Cytochrome C: an electron paramagnetic resonance investigation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 1994;3:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Husseini GA, Diaz MA, Richardson ES, Christensen DA, Pitt WG. The Role of Cavitation in Acoustically Activated Drug Delivery. J Controlled Release. 2005;107(2):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stevenson-Abouelnasr D, Husseini GA, Pitt WG. Further investigation of the mechanism of Doxorubicin release from P105 micelles using kinetic models. Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces. 2007;55(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marin A, Muniruzzaman M, Rapoport N. Mechanism of the ultrasonic activation of micellar drug delivery. J Control Rel. 2001;75:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rapoport N. Combined cancer therapy by micellar-encapsulated drug and ultrasound. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2004;227:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rapoport N, Marin A, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Munirzzaman M. Intracellular uptake and trafficking of Pluronic micelles in drug-sensitive and MDR cells: Effect on the intracellular drug localization. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(1):157–170. doi: 10.1002/jps.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marin A, Muniruzzaman M, Rapoport N. Acoustic activation of drug delivery from polymeric micelles: effect of pulsed ultrasound. J Controlled Rel. 2001;71:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pruitt JD, Husseini G, Rapoport N, Pitt WG. Stabilization of Pluronic P-105 Micelles with an Interpenetrating Network of N,N-Diethylacrylamide. Macromolecules. 2000;33(25):9306–9309. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pruitt JD, Pitt WG. Sequestration and Ultrasound-Induced Release of Doxorubicin from Stabilized Pluronic P105 Micelles. Drug Deliv. 2002;9(4):253–259. doi: 10.1080/10717540260397873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Husseini GA, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic release of doxorubicin from Pluronic P105 micelles stabilized with an interpenetrating network of N,N-diethylacrylamide. J Controlled Rel. 2002;83(2):302–304. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeng Y, Pitt WG. Poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles with crosslinked cores as drug carriers. J Biomat Sci Polym Ed. 2005;16(3):371–380. doi: 10.1163/1568562053654121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Husseini GA, Diaz MA, Zeng Y, Christensen DA, Pitt WG. Release of Doxorubicin from Unstabilized and Stabilized Micelles Under the Action of Ultrasound. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2006 doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.218. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nelson JL, Roeder BL, Carmen JC, Roloff F, Pitt WG. Ultrasonically Activated Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery in a Rat Model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7280–7283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Staples BJ, Roeder BL, Pitt WG. Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. April 26-29, 2006; 2006. p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Staples BJ. Chemical Engineering Department, MS Thesis. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University; 2007. Pharmacokinetics of Ultrasonically-Released, Micelle-Encapsulated Doxorubicin in the Rat Model and its Effect on Tumor Growth. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gao Z, Fain HD, Rapoport N. Ultrasound-Enhanced Tumor Targeting of Polymeric Micellar Drug Carriers. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2004;1(3):317–330. doi: 10.1021/mp049958h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rapoport N, Christensen DA, Fain HD, Barrows L, Gao Z. Ultrasound-triggered drug targeting of tumors in vitro and in vivo. Ultrasoincs. 2004;42:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2004.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Daniels S, Blondel D, Crum LA, ter Haar GR, Dyson M. Ultrasonically induced gas bubble production in agar based gels: Part I, experimental investigation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1987;13(9):527–539. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(87)90179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill CR. Ultrasonic Exposure Thresholds for Changes in Cells and Tissues. J Acoust Soc Am. 1971;52(2):667–672. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brennen CE. Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Urick RJ. Principles of Underwater Sound. 3. San Francisco: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1983. p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuijpers MWA, van Eck D, Kemmere MF, Keurentjes JTF. Cavitation-induced reactions in high-pressure carbon dioxide. Science. 2002;298(5600):1969–1971. doi: 10.1126/science.1078022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barnett S. Thresholds for Nonthermal Biofeffects: Theoretical and Experimental Basis for a Threshold Index. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1998;24(S1):S41–S49. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huber PE, Mann MJ, Melo LG, Ehsan A, Kong D, Zhang L, Rezvani M, Peschke P, Jolesz F, Dzau VJ, Hynynen K. Focused ultrasound (HIFU) induces localized enhancement of reporter gene expression in rabbit carotid artery. Gene Therapy. 2003;10(18):1600–1607. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hynynen K, McDannold N, Martin H, Jolesz FA, Vykhodtseva N. The threshold for brain damage in rabbits induced by bursts of ultrasound in the presence of an ultrasound contrast agent (Optison (R)) Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2003;29(3):473–481. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00741-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miller DL, Thomas RM. Thresholds for Hemorrhages in Mouse Skin and Intestine Induced by Lithotripter Shock Waves. Ultrasound in Med Biol. 1995;21(2):249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(94)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mitragotri S, Farrell J, Tang H, Terahara T, Kost J, Langer R. Determination of Threshold Energy Dose for Ultrasound-Induced Transdermal Drug Transport. J Control Rel. 2000;63(12):41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mitragotri S, Ray D, Farrell J, Tang H, Yu B, Kost J, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Synergistic effect of low-frequency ultrasound and sodium lauryl sulfate on transdermal transport. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2000;89(7):892–900. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200007)89:7<892::AID-JPS6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saad AH, Williams AR. Effects of Therapeutic Ultrasound on Clearance Rate of Blood Borne Colloidal Partricles in vivo. Br J Cancer. 1982;45 V:202–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tachibana K, Tachibana S. Albumin Microbubble Echo-Contrast Material as an Enhancer for Ultrasound Accelerated Thrombolysis. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1148–1150. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tezel A, Sens A, Tuchscherer J, Mitragotri S. Frequency Dependence of Sonophoresis. Pharmaceutical Research. 2001;18(12):1694–1700. doi: 10.1023/a:1013366328457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nyborg WL. Biological Effects of Ultrasound: Development of Safety Guidelines. Part II: General Review. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27(3):301–333. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sundaram J, Mellein BR, Mitragotri S. An experimental and theoretical analysis of ultrasound-induced permeabilization of cell membranes. Biophys J. 2003;84(5):3087–3101. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tezel A, Sens A, Mitragotri S. Investigations of the role of cavitation in low-frequency sonophoresis using acoustic spectroscopy. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(2):444–453. doi: 10.1002/jps.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mitragotri S. Synergistic Effect of Enhancers for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharm Res. 2000;17(11):1354–1357. doi: 10.1023/a:1007522114438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tang H, Wang CCJ, Blankschtein D, Langer R. An investigation of the role of cavitation in low-frequency ultrasound-mediated transdermal drug transport. Pharmaceutical Research. 2002;19(8):1160–1169. doi: 10.1023/a:1019898109793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu J, Lewis TN, Prausnitz MR. Non-Invasive Assessment and Control of Ultrasound-Mediated Membrane Permeabilization. Pharm Res. 1998;15(6):918–924. doi: 10.1023/a:1011984817567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rooney JA. Hemolysis Near an Ultrasonically Pulsating Gas Bubble. Science. 1970;169:869–871. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3948.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gudra T, Opielinski KJ. Applying spectrum analysis and cepstrum analysis to examine the cavitation threshold in water and in salt solution. Ultrasonics. 2004;42(19):621–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Johri GK, Singh D, Johri M, Saxena S, Iernetti G, Dezhkunov N, Yoshino K. Measurement of the intensity of sonoluminescence, subharmonic generation and sound emission using pulsed ultrasonic technique. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics Part 1-Regular Papers Short Notes & Review Papers. 2002;41(8):5329–5331. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Neppiras EA. Subharmonic and Other Low-Frequency Emission from Bubbles in Sound-Irradiated Liquids. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1968;46(3):187–601. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Leighton TG. The Acoustic Bubble. London: Academic Press; 1994. p. 613. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Flynn HG, Church CC. Transient pulsations of small gas bubbles in water. J Acoust Soc Am. 1988;84(5):1863–1876. doi: 10.1121/1.397253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Eller A, Flynn HG. Generation of Subharmonics of Order One-Half by Bubbles in a Sound Field. J Acoustical Soc Amer. 1969;46(3):722–727. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Neppiras EA. Subharmonic and Other Low-Frequency Emission from Bubbles in Sound-Irradiated Liquids. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1969;46(3):587–601. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Diaz-De-La-Rosa MA. High-Frequency Ultrasound Drug Delivery and Cavitation Chemical Engineering Department. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nyborg WL. Ultrasonic Microstreaming and Related Phenomena. Br J Cancer. 1982;45 V:156–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fairbairn DW, Olive PL, O'Neill KL. The comet assay: a comprehensive review. Mutation Res. 1995;339:37–59. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(94)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fairbairn DW, O'Neill KL. Letter to the Editor: Necrotic DNA Degradation Mimics Apoptotic Nucleosomal Fragmentation Comet Tail Length. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1995;31:171–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02639429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fairbairn JJ, Khan MW, Ward KJ, Loveridge BW, Fairbairn DW, O'Neill KL. Induction of apoptotic cell DNA fragmentation in human cells after treatment with hyperthermia. Cancer Letters. 1995;89:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)03668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fairbairn DW, Neill KLO. The neutral comet assay is sufficient to identify an apoptotic ‘window’ by visual inspection. Apoptosis. 1996;1:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fairbairn DW, Walburger DK, Fairbairn JJ, O'Neill KL. Key Morphologic Changes and DNA Strand Breaks in Human Lymphoid Cells: Discriminating Apoptosis from Necrosis. Scanning. 1996;18:407–416. doi: 10.1002/sca.1996.4950180603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Husseini GA, O'Neill KL, Pitt WG. The comet assay to determine the mode of cell death for the ultrasonic delivery of doxorubicin to human leukemia (HL-60 cells) from pluronic P105 micelles. Technol Cancer Res T. 2005;4(6):707–711. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Husseini GA, Runyan CM, Pitt WG. Investigating the mechanism of acoustically activated uptake of drugs from Pluronic micelles. BMC Cancer. 2002;2(20):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sheikov N, McDannold N, Jolesz F, Zhang YZ, Tam K, Hynynen K. Brain arterioles show more active vesicular transport of blood-borne tracer molecules than capillaries and venules after focused ultrasound-evoked opening of the blood-brain barrier. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32(9):1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schlicher RK, Radhakrishna H, Tolentino TP, Apkarian RP, Zarnitsyn V, Prausnitz MR. Mechanism of intracellular delivery by acoustic cavitation. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2006;32(6):915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.02.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Stringham SB, Murray BK, O'Neill KL, Ohmine S, Gaufin TA, Pitt WG. 96th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; Anaheim, CA, USA. April 16-20, 2005; 2005. p. 1415. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yamashita N, Tachibana K, Ogawa K, Tsujita N, Tomita A. Scanning Electron Microscopic Evaluation of the Skin Surface After Ultrasound Exposure. Anatom Rec. 1997;247:455–461. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199704)247:4<455::AID-AR3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tachibana K, Uchida T, Ogawa K, yamashita N, Tamura K. Induction of cell-membrane porosity by ultrasound. Lancet. 1999;353:1409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ogawa K, Tachibana K, Uchida T, Tai T, Yamashita N, Tsujita N, Miyauchi R. High-resolution scanning electron microscopic evaluation of cell-membrane porosity by ultrasound. Med Electron Microsc. 2001;34(4):249–253. doi: 10.1007/s007950100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Miura S, Tachibana K, Okamoto T, Saku K. In vitro transfer of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides into coronary endothelial cells by ultrasound. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298(4):587–590. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]