Abstract

The acronym COACH defines an autosomal recessive condition of Cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, Oligophrenia, congenital Ataxia, Coloboma and Hepatic fibrosis. Patients present the “molar tooth sign”, a midbrain-hindbrain malformation pathognomonic for Joubert Syndrome (JS) and Related Disorders (JSRDs). The main feature of COACH is congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF), resulting from malformation of the embryonic ductal plate. CHF is invariably found also in Meckel syndrome (MS), a lethal ciliopathy already found to be allelic with JSRDs at the CEP290 and RPGRIP1L genes. Recently, mutations in the MKS3 gene (approved symbol TMEM67), causative of about 7% MS cases, have been detected in few Meckel-like and pure JS patients. Analysis of MKS3 in 14 COACH families identified mutations in 8 (57%). Features such as colobomas and nephronophthisis were found only in a subset of mutated cases. These data confirm COACH as a distinct JSRD subgroup with core features of JS plus CHF, which major gene is MKS3, and further strengthen gene-phenotype correlates in JSRDs.

Keywords: COACH syndrome, MKS3, TMEM67, Joubert syndrome and related disorders, congenital hepatic fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

COACH syndrome (Cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, Oligophrenia, congenital Ataxia, Coloboma and Hepatic fibrosis; MIM# 216360) is a rare autosomal recessive multisystemic disorder first described in 1974 in two siblings (Hunter, 1974), and later delineated as a distinct clinical entity by Verloes and Lambotte (1989). In 1997, Maria and coworkers described a peculiar midbrain-hindbrain malformation, which they termed “molar tooth sign” (MTS), characterized by cerebellar vermis hypo-dysplasia, thickening and horizontalization of superior cerebellar peduncles and deepening of the interpeduncular fossa (Maria et al., 1997). The MTS was first identified in Joubert syndrome (JS; MIM# 213300), characterized by hypotonia evolving into ataxia, developmental delay, mental retardation, neonatal breathing abnormalities, oculomotor apraxia and nystagmus, and subsequently recognized in an expanding group of malformative conditions, presenting the typical JS features along with variable involvement of other organs, mainly the eyes and kidneys. These were first reviewed in 1999 as “cerebello-oculo-renal syndromes”, and later expanded by Gleeson and co-workers, who listed eight distinct MTS-related conditions under the term “Joubert Syndrome Related Disorders” (JSRDs), including Senior-Loken, Varadi-Papp (or Oro-Facio-Digital type VI), MALTA and COACH syndromes (Satran et al., 1999; Gleeson et al., 2004).

Among the vast group of JSRDs, COACH syndrome presents the unique association of neurological manifestations with congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF). Other features first described as part of the COACH phenotype, such as chorioretinal coloboma and nephronophthisis (NPH), are only inconstantly found in association with CHF, while can be variably detected in other JSRDs lacking liver involvement (Gleeson et al., 2004). A variant of COACH syndrome with only JS and CHF, reported in a few patients (Gentile et al., 1996; Coppola et al., 2002), was also termed “Gentile syndrome”. Phenotypic manifestations of CHF may vary from a clinically asymptomatic raise of liver enzymes and/or early-onset hepatosplenomegaly to more severe manifestations including portal hypertension, esophageal varices and liver cirrhosis. The pathophysiology of CHF results from an arrest of the embryonic development of intrahepatic bile ducts at the stage of bilaminar plate formation, defined as “ductal plate malformation” (DPM) (Desmet, 1992). Intriguingly, DPM is also characteristic of Meckel syndrome (MS; MIM# 249000) (Sergi et al., 2000), an autosomal recessive syndrome with early lethality, whose diagnostic criteria are occipital encephalocele, cystic dysplasia of the kidneys, CHF and/or other central nervous system (CNS) malformations (Salonen, 1984).

Besides CHF, the clinical overlap between JSRDs and MS extends to several other features such as multicystic dysplastic kidneys (although with different localization and size of the cysts), post-axial polydactyly and CNS manifestations including encephalocele, heterotopia, agenesis of the corpus callosum and Dandy-Walker malformation. Moreover, a Meckel-like phenotype has been described in fetuses lacking at least one MS diagnostic criterion and showing renal/hepatic involvement and atypical CNS malformations resembling the MTS. Indeed, JSRDs and MS have been recently proven to be allelic conditions related to genes encoding for proteins of the primary cilium, thus belonging to the expanding family of ciliopathies. In particular, mutations in the CEP290 and RPGRIP1L genes, mainly associated with the cerebello-oculo-renal and the cerebello-renal JSRD phenotypes respectively, have been subsequently shown to cause typical MS (Baala et al., 2007a; Frank et al., 2008; Delous et al., 2007). The MKS3 gene (HUGO-approved symbol, TMEM67; MIM# 609884), encoding the transmembrane protein meckelin, was firstly found mutated in MS (Smith et al., 2006), of which it causes about 7% cases (Consugar et al., 2007; Khaddour et al., 2007). Recently, Baala and colleagues reported MKS3 mutations in two JSRD patients showing a pure cerebellar phenotype, in two fetuses from one family with Meckel-like syndrome and in a fifth patient with a cerebello-renal phenotype associated with liver involvement, in whom the MTS could not be demonstrated (Baala et al., 2007b). Based on these observations, we speculated whether MKS3 mutations might be responsible for COACH syndrome and performed mutation analysis of the MKS3 gene in 14 probands.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the CSS Hospital and the University of California San Diego. Appropriate informed consent was obtained from all families. Among 198 JSRD families for which detailed clinical data were available, 14 probands showing typical neurological and neuroradiological signs of JS associated with CHF were selected for MKS3 analysis. The MTS could be confirmed by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 13 probands. We also included in the screening one of the originally described COACH families (MTI124), that was recently re-evaluated. In this family, no brain MRI was available but a CT scan demonstrated cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia and cerebellar clefting in both affected siblings (Verloes and Lambotte, 1989). The diagnosis of CHF was based on liver biopsy in all but two probands (COR32 and COR190), who presented hepatomegaly from birth, liver enzymes repeatedly elevated over twice the normal values and bile ducts dilatation suggestive of CHF at liver MRI. Additional clinical manifestations such as chorioretinal colobomas and nephronophthisis, although supportive of the diagnosis of COACH, were not considered mandatory inclusion criteria for this study.

Mutation screening

The 28 exons and the exon-intron boundaries of the MKS3 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and, after purification, were bi-directionally sequenced using BigDye Terminator chemistry and an ABI Prism Sequencer 3100 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, www.appliedbiosystems.com). PCR primers and conditions are listed in Table 1. Sequences were analyzed using the SeqMan software from Lasergene package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, http://www.dnastar.com/products/lasergene.php). Nucleotide mutation numbering was based on cDNA sequence, with a ‘c.’ symbol before the number, +1 being the first nucleotide of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence (see Bioinformatic analysis). Gene dosage analysis to detect MKS3 heterozygous exon rearrangements was not performed.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR conditions for MKS3 analysis

| Exon | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) | amplicon size (bp) | PCR anneal. temp. (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TCCAATCAGCTCAGCGAAGC | GGGAGTGTTACTTTTGCCAG | 339 | 60 |

| 2 | TAGGAACTTCATGTGTATGTC | CTTACTACTTTTTACAGGTAAG | 139 | 56–52 TD |

| 3 | CTCTTATGGCATTTTGAACTTAC | AGAATGAAGATTTATCACTACTTC | 224 | 56–52 TD |

| 4 | ATAATAGTTACAATTGGGTTTTG | GATATTAATGAAGTTAGCCCC | 236 | 56 |

| 5 | CTGAATGAATCTACTCTAATCC | TATGAAAAGGCATAAGCAACTG | 236 | 55 |

| 6 | ATTCAGTTGCTTATGCCTTTTC | TCTAGCCTGAAATTACTAATGG | 209 | 56 |

| 7 | GTGAGACATTTCCCATTCAAC | TGACCAAGAAGCTATAGCTAC | 249 | 62–55 TD |

| 8 | GACTGTTCAGGTTCATGTTAC | AATAACTGCACTGAATTCAGTC | 257 | 55 |

| 9 | CTCCATTATTAAAACAGTTGTAAC | CAAAATGTAGTTATCCTCTAATG | 182 | 56–52 TD |

| 10 | TACTTTCAGAGTATTTGACCTG | TCCTCTTGGCTTTGTCTCAG | 200 | 56 |

| 11 | CGGGTTTGAGAACTCTTGAG | TATTCCAATTACTGCTGACATG | 211 | 56 |

| 12 | CTTTAAGTTGCTGTTTTATGTGC | CTCAGGGAAAAGAGTGGTATG | 240 | 57 |

| 13 | GCTTTTTGCAGCCATCTTATC | CTGGCAAACACTTCCATTATG | 266 | 55 |

| 14 | TTTAAAGGCCCGGATATACTG | CTCTATTTATACATACAAGGGC | 200 | 55 |

| 15 | GGTAAAACCCAGCTACAAATG | TAGCAACTTCTTGCACATCTG | 228 | 56–52 TD |

| 16 | TGTTTTTGAACACCGATGACA | TGAGAAGGATCCAGAATGGTC | 220 | 55 |

| 17 | TACATGGAGTCTTAAACAGCTG | TTCAACTATTCAGATATTGGCAG | 194 | 57 |

| 18 | TGTGTGTGATAATATTTAATCAAG | GACTTGTTAGTTCATTAGCAGG | 185 | 56–52 TD |

| 19 | AAGCAGACTTAACGCTGGTAC | CCTTTGCTCTGCAAGGGTAG | 213 | 56 |

| 20 | CCCTTGCAGAGCAAAGGAG | CATGTAAGTCGCATATAATCAC | 233 | 62–56 TD |

| 21 | GTTTTCTTTATCCATGTCCGTTT | TGCTACAGAAAGAAGGATGTGGT | 300 | 55 |

| 22 | AAGATGCTACACTGTGGCTG | GAAAGTAACAGTTGCAAGATG | 197 | 62–56 TD |

| 23 | TGCAGATGAGTTGCTATTTGCT | TTCTCAACTTAAAAACAAAAAGATG | 203 | 56 |

| 24 | CTGTATTTTCTTTTTGAGGCAG | GACAGAATATATCTGAACTGTAC | 221 | 56 |

| 25 | GATACCAAGAACATAACACTTTG | GTTTACTGACTTGGTTGACTTG | 255 | 62–56 TD |

| 26 | ACTACTGTTTGTGAAATGATGC | GAAAACAGTTATCAAGTTCTAC | 184 | 58–54 TD |

| 27 | CAGAAGTTTATCACAGACTTG | CTACTTCTAACATATTTCTCTC | 274 | 56–52 TD |

| 28 | GATTCAGATACCTGATACATG | GGCCATGATTATACTGAGTC | 249 | 56–52 TD |

TD: touch-down PCR

RNA analysis

To assess the effect of the c.G1961-2A>C mutation at the mRNA level (family COR09), total RNA of the proband was extracted from lymphocytes using standard techniques and cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR amplification using SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, www.invitrogen.com), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Exonic primers were designed within exons 16 and 21 to amplify a 477bp fragment of MKS3 cDNA (forward: 5′-TCTTTTGAAGACAGCAGGATGG-3′; reverse: 5′-TGCTAAGTTCTTGAATCCCAC-3′).

Polymerase chain reaction was performed in a final volume of 30 μL containing 100 ng cDNA; 0.5 pmol of each primer; 0.2 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 6 μL 5× buffer, and 1.25 Unit of DNA polymerase (GoTaq DNA Polymerase; Promega, Madison, WI, www.promega.com). Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes was followed by 38 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, annealing at 56°C, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds each. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 7 minutes.

PCR products were resolved on a 2,5% MS-12 agarose gel, and generated a single band of the expected size in the control sample and one additional smaller band in the proband. After single-band gel excision and purification by GFX-PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc. Piscataway, NJ, http://www.amershambiosciences.com), each of the amplified fragments was directly sequenced in both forward and reverse directions.

Bioinformatic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments of the human meckelin protein and its orthologues were generated using the ClustalW program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). Prediction of the possible impact of missense variants on meckelin was obtained with PolyPhen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/). Prediction of the effect of splice site mutations on MKS3 RNA splicing was tested using SSF software (http://www.umd.be/SSF).

Accession numbers were taken from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/) or Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html) databases, as follows: human MKS3 cDNA sequence: NM_153704.4; meckelin protein sequences: Homo sapiens, NP_714915.3 or ENSP00000314488; Macaca mulatta, ENSMMUP00000007350; Rattus norvegicus, ENSRNOP00000021839; Mus musculus, ENSMUSP00000052644; Gallus Gallus, ENSGALP00000025642; Tetraodon Nigroviridis, GSTENP00034026001; Drosophila melanogaster, FBpp0112166; Caenorhabditis elegans F35D2.4.

RESULTS

Among 14 COACH families screened, eight carried mutations in MKS3 (57%) for a total number of 12 affected individuals. In seven families, affected members were compound heterozygous, while in one family (COR191) only one mutated allele could be identified. In this case, RNA was not available for further investigations.

MKS3 mutational spectrum

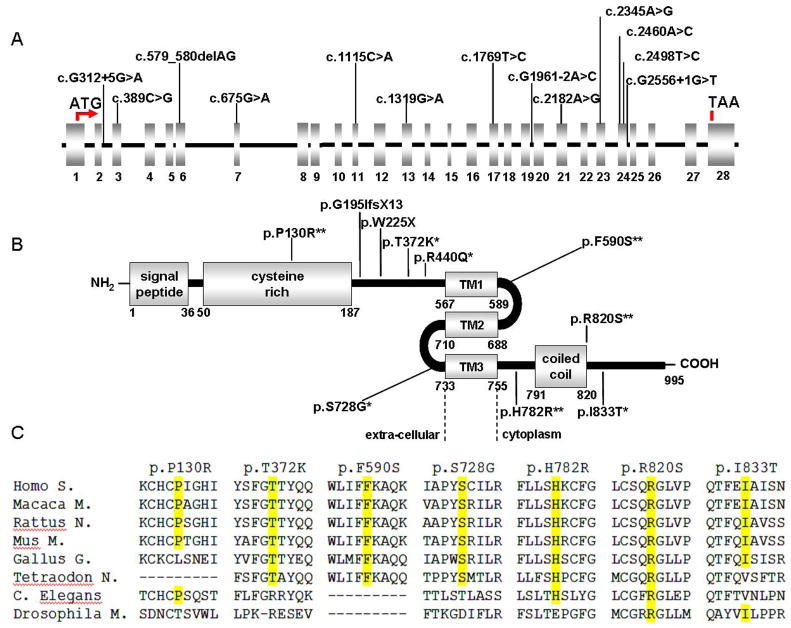

Thirteen distinct mutations were identified (Figure 1), of which all were novel but p.R440Q, previously reported in compound heterozygosity in two MS families (Consugar et al., 2007; Khaddour et al., 2007). The 12 novel mutations include two truncating mutations (one frameshift and one nonsense), seven missense changes and three splice-site mutations. Segregation of mutations with the disease was verified in all families.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic of the MKS3 gene (cDNA reference sequence: NM_153704.4) and B) of the meckelin protein (reference sequence: NP_714915.3) with mutations identified in the present study (*, possibly damaging; ** probably damaging). Splice site mutations are not represented at the protein level. TM, predicted transmembrane domains (Khaddour et al., 2007). C) Conservation across species (shaded in yellow) of residues affected by novel missense variants.

All missense mutations were absent in 500 control chromosomes, and alignment with meckelin orthologues showed all affected residues to be highly conserved among different species (Figure 1C). Moreover, bioinformatic analysis using PolyPhen software indicated that all missense mutations were probably or possibly damaging, with PSIC scores ranging between 1.5 and 2.5 (values >1.0 are considered predictive of a variant being damaging) (Sunyaev et al., 2001). The three splice site mutations were assessed using SSF software. Mutations c.G1961-2A>C and c.G2556+1G>T were predicted to abolish the canonical 3′-splice site in intron 19 and 5′-splice site in intron 24 respectively, while c.G312+5G>A was predicted to weaken the 5′-splice site in intron 2.

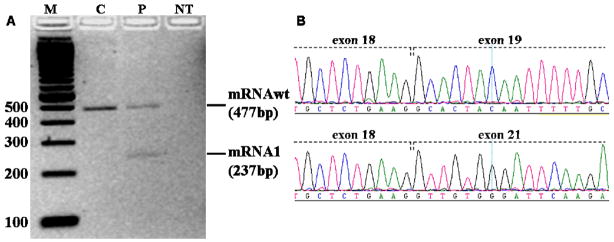

Characterization of the c.G1961-2A>C splice site mutation

RNA from the proband was obtained in family COR09, in which the two affected siblings inherited the c.G1961-2A>C change from their mother and the c.1769T>C (p.F590S) mutation from their father. RT-PCR with primers located in MKS3 exons 16 and 21 revealed the presence of the expected wild-type fragment (477bp) in the normal control, while the proband presented two distinct bands, corresponding to the wild type fragment and to a novel fragment of about 230 bp (mRNA1). Sequencing of mRNA1 demonstrated the skipping of exons 19 and 20, resulting in the abnormal transcript r.1861_2100del (Figure 2). This is predicted to generate a shorter protein lacking 80 amino acids (p.A621_E700del) that are part of the loop between putative transmembrane domains 1 and 2, and of the second transmembrane domain (Figure 1B).

Figure 2.

Characterization of the splicing mutation c.G1961-2A>C in family COR09. A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the 477bp cDNA fragment showing the generation of an abnormal band of approximately 230bp in the proband. B) Electropherograms of the two fragments from the proband: mRNAwt shows the expected exon 18–19 junction, while mRNA1 presents an abnormal exon18–21 junction, with skipping of exons 19 and 20. M: 100bp marker; C: control; P: proband; NT: no transcript.

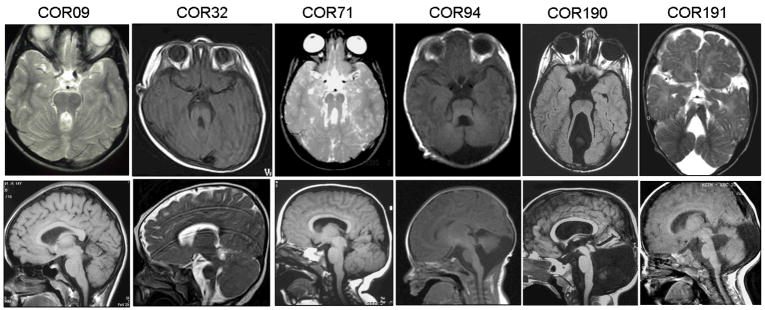

Phenotypes of MKS3 mutated patients

Clinical features of MKS3-mutated patients are presented in Table 2. Neuroradiological imaging of six mutated probands are presented in Figure 3, while brain MRI of COR20 and CT scan of MTI124 families have been published before (Coppola et al., 2002; Verloes and Lambotte, 1989). Three patients (25%) present a more severe malformation of the posterior fossa, with severe vermis hypoplasia (COR94 and 191) or vermis aplasia and global cerebellar hypoplasia (COR190) associated with subtentorial cystic dilatation of the cisterna magna communicating with the fourth ventricle. All mutated patients had neurological signs typical of JS. Mental retardation was always moderate to severe, with some patients even unable to speak and read. Additional neurological signs included seizures in two patients (17%), choreodystonic movements of the limbs in two (17%) and deep tendon hyperreflexia in five cases (42%). Breathing abnormalities in the neonatal period were reported only in four cases (33%), while oculomotor apraxia was present in 9 (75%).

Table 2.

Phenotypes of MKS3 mutated patients

| Family ID/country of origin | Nucleotide change (exon) | Protein mutation | Sex/YOB | Age at last exam | Central Nervous System | Liver | Retina | Kidney | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR09/Italy1 | c.1769T>C (17) | p.F590S | M/1978† | 14 yrs | MTS, H, A, DD, MR, OMA, N | ELE, CHF, HM, EV, LT | - | - | - |

| c.G1961-2A>C | splice | M/1991 | 17 yrs | MTS, H, DD, MR, OMA, N | ELE, CHF, HM, EV | - | - | - | |

| COR20/Italy2 | c.579_580delAG (6) | p.G195IfsX13 | M/1991 | 8 yrs | MTS, A, DD, MR, OMA, N | ELE, CHF | - | - | - |

| c.1769T>C (17) | p.F590S | F/1998 | 3 yrs | MTS, H, A, DD, MR, OMA | CHF | - | - | - | |

| COR32/Italy | c.1115C>A (11) | p.T372K | M/2002 | 6 yrs | MTS, AB, H, DD, MR, OMA | BDD, HM | Co | RKA | - |

| c.2345A>G (23) | p.H782R | M/2007 | 1 yr | MTS, H, DD, OMA, N | ELE | Co | - | - | |

| COR71/Italy | c.389C>G (3) | p.P130R | F/1991 | 20 yrs | MTS, H, A, DD, MR, OMA | ELE, CHF, HM | Co | NPH, ESRF | HR, U |

| c.675G>A (7) | p.W225X | ||||||||

| COR94/Italy | c.1319G>A (13) | p.R440Q | M/2005 | 3 yrs | MTS, AB, H, DD, MR, OMA, | ELE, CHF, HM | Co | - | CD, HR, U |

| c.2182A>G (21) | p.S728G | N | |||||||

| COR190/Croatia | c.G312+5G>A | splice | F/1998 | 9 yrs | MTS, EC, AB, H, A, DD, MR, | ELE, BDD, HM | EOC | NPH, CRF | CD, HR |

| c.2498T>C (24) | p.I833T | OMA, Sz | |||||||

| COR191/Croatia | c.2460A>C (24) | p.R820S | M/1998 | 9 yrs | MTS, AB, A, DD, MR, N, Sz | ELE, CHF, HM | POD | NPH, ESRF | HR |

| ? | ? | M/- | fetus§ | CVA, EC | CHF | - | CK | P | |

| MTI124/Belgium3 | c.2498T>C (24) | p.I833T | F/1971 | 32 yrs | CVA, H, A, DD, MR | ELE, CHF, HM | Co | NPH, ESRF | D, U |

| c.G2556+1G>T | splice | M/1974† | 29 yrs | CVA, H, A, DD, MR, N | CHF, HM, EV | - | NPH, CRF | HR, U |

YOB: year of birth; †: deceased. Central Nervous System: A: ataxia; AB: abnormal breathing; CVA: cerebellar vermis aplasia; DD: developmental delay; EC: encephalocele; H: hypotonia; MR: mental retardation; MTS: molar tooth sign; N: nystagmus; OMA: oculomotor apraxia; Sz: seizures. Liver: BDD: bile ducts dilatation at liver MRI; CHF: congenital hepatic fibrosis at liver biopsy; ELE: elevated liver enzymes; EV: esophageal varices; HM: hepatomegaly; LT: liver transplant. Retina: Co: colobomas; EOC: enlarged optic cup; POD: pale optic disk. Kidney: CK: cystic kidneys; CRF: chronic renal failure; ESRF: end stage renal failure; NPH: nephronophthisis; RKA: right kidney agenesis. Other: CD: choreo-dystonic movements; D: diabetes following acute pancreatitis; HR: hyperreflexia; P: polydactyly; U: undergrowth (heigh and weight < 3rd centile). §DNA not available.

described in Gentile et al., 1996;

described in Coppola et al., 2002 (patients 1 and 2);

described in Verloes and Lambotte, 1989 (patients 1 and 2). Mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence with a “c.” symbol before the number, where +1 corresponds to the A of ATG start translation codon of the cDNA reference sequence (NM_153704.4). Human meckelin reference sequence, NP_714915.3.

Figure 3.

Axial (upper lane) and median sagittal (lower lane) brain MRI sections of six probands showing the typical “molar tooth sign” and associated CNS malformations (see text).

Liver disease ranged from clinically mild, with only hepatomegaly and fluctuating raise of aminotransferases and/or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase that could be well controlled by ursodesoxycholate therapy, to severe progressive forms leading to icterus, portal hypertension, esophageal varices, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Chorioretinal or optic nerve colobomas were detected in five patients (42%). In two further cases, slit-lamp examination could not be performed, but fundoscopy revealed abnormalities such as enlarged optic cup or pale optic disc, that could be part of the same malformative spectrum (Gregory-Evans et al., 2004). NPH was detected in four patients (33%), while a fifth patient was reported to have agenesis of one kidney. In family COR191, the second pregnancy was terminated after prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of MS. Pathological examination of the aborted fetus confirmed the diagnosis by showing cystic dysplastic kidneys, ductal plate malformation with marked portal fibrosis and cystic enlargement of bile ducts, polydactyly, occipital encephalocele and cerebellar vermis aplasia.

DISCUSSION

We report the identification of MKS3 mutations in eight of 14 (57%) JSRD families with congenital liver fibrosis, expanding the allelic spectrum of MKS3 to include COACH syndrome. This mutation frequency is notably higher than the 7% figure observed in MS (Consugar, 2007; Kaddour, 2007), indicating a major role for MKS3 within this specific JSRD subtype. These findings add a relevant contribution to the emerging gene-phenotype correlates in JSRDs, that are leading to a novel clinical-molecular classification based on the degree of multiorgan involvement and the outcome of large mutation screens of known genes (Valente et al., 2008). Besides pure JS and JS plus retinopathy (for which the major gene is AHI1), JS plus renal involvement (mostly caused by NPHP1 or RPGRIP1L mutations) and cerebello-oculo-renal phenotypes (strongly associated to CEP290 mutations), we now suggest to include a fifth subgroup termed “JS plus CHF”, that encompasses the COACH acronym. In this subgroup, which major gene is MKS3, CHF is the only mandatory criterion while other COACH-related features such as colobomas and renal involvement are possible additional manifestations. Interestingly, none of the 12 mutated patients had Leber congenital amaurosis or other forms of retinal dystrophy, that are frequently detected in other JSRD subgroups. This is unlikely to reflect a selection bias since patients were ascertained on the basis of CHF associated with JS signs, regardless of ocular abnormalities. Indeed, two of the six MKS3-negative patients presented with retinopathy in the absence of chorioretinal coloboma.

In our cohort, CHF could be histologically confirmed in most cases by liver biopsy, and only in two families it was diagnosed based on elevated liver enzymes, hepatomegaly and intrahepatic bile duct dilatation at liver MRI. The clinical presentation of CHF appears to be extremely variable and often subtle in young children, with liver function and ultrasound that may remain normal or just show minor abnormalities for several years before becoming symptomatic, even acutely. In light of these findings, young JSRD patients with hepatomegaly and/or persistent elevation of liver enzymes should always undergo a detailed assessment of hepatic function, since an early diagnosis of CHF is crucial for a timely management of complications.

The clinical variability observed in our MKS3-mutated families, related not only to the occurrence of ocular and renal involvement but also to the extent and severity of neurological and liver disease, still remains unexplained. A possible explanation comes from Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS; MIM# 209900), a ciliopathy consisting of retinopathy, polydactyly, obesity, hypogenitalism and posterior fossa defects due to mutations in at least 12 distinct genes. Recent studies have unmasked an oligogenic way of inheritance, in which mutations at different BBS loci can epistatically interact to cause and/or modify the phenotype (Badano et al., 2006), and such mechanism has recently been demonstrated also for NPH genes (Hoefele et al. 2007). Thus, epistatic effects of mutated alleles in other JSRD/MS genes are likely to explain at least in part the observed variability, as it has been already suggested for NPHP1, AHI1 and CEP290 genes (Tory, 2007). Of note, Wolf et al. (2007) reported two patients with JS plus CHF and renal involvement who carried a single mutated allele in the RPGRIP1L gene. It is tempting to speculate that these patients carry distinct mutations in MKS3 or in another, still unidentified gene, and that mutations in RPGRIP1L could represent modifier factors for NPH development. A similar speculation could apply to our family COR191, in which the living proband had a typical COACH phenotype while the aborted fetus met the diagnostic criteria for MS. In this family only one MKS3 mutated allele could be identified in the proband, and DNA was not available from the fetus for molecular analysis. Although a second MKS3 mutation unidentified by conventional sequencing cannot be excluded, the possible co-occurrence of mutations in other JSRD/MS genes is currently being tested.

Out of seven MKS3 compound heterozygous families reported here, five showed an association of splicing or truncating mutations with missense changes, while two were compound heterozygous for missense variants. Interestingly, one splice site mutation resulted in the simultaneous skipping of two consecutive exons (19 and 20). A possible explanation for this unusual phenomenon is that the mutation-induced skipping of one exon could result in a loss of exonic splice enhancers (ESE) required to stimulate splicing efficiency of flanking adjacent exons. This is true especially in case of small exons/introns and weak splice sites, as in MKS3 exon/intron 19 (van Wijk et al., 2004).

None of the patients carried two mutations leading to premature truncation of meckelin, in line with previously reported MKS3-mutated JS and Meckel-like patients (Baala et al., 2007b). Conversely, abolition of meckelin activity is frequently reported in MS patients (Smith et al., 2005; Consugar et al., 2007; Khaddour et al., 2007), supporting the hypothesis that complete loss of function could lead to a more severe, early lethal phenotype while patients retaining some protein activity would develop a milder JSRD phenotype. Notably, hypomorphic mutations in the NPHP3 gene are responsible for juvenile NPH with retinal dystrophy and liver fibrosis (Olbrich et al., 2003), while loss of function mutations in the same gene have been recently found to cause an early lethal Meckel-like syndrome with CHF, cystic dysplastic kidneys, variable laterality defects, and CNS malformations (Bergmann et al., 2008).

In our cohort, missense mutations were found throughout the protein, in contrast with MS-associated missense mutations that mostly cluster in the extracellular domain of meckelin. A possible explanation is that the extracellular domain, containing a cleavable peptide and a cystein-rich repeat region superficially similar to EGF, EGF-CA and laminin EGF repeats, is more critical to meckelin function than other protein domains. This would be in line with the proposed role of meckelin as a receptor, based on structural evidences and on similarities to the G-protein coupled and Frizzled receptor families (Smith et al., 2005).

Meckelin has been shown to locate to proximal renal tubules and biliary epithelial cells where it plays an essential role in formation of the primary cilium, a sophisticated organelle found in most epithelial tissues and also in developing neurons (Dawe et al., 2007). Increasing evidence points to a fundamental role for primary cilia in bile duct morphogenesis and renal tubulo-epithelial differentiation during embryogenesis, as well as in regulating key pathways of embryonic development, such as those involving Sonic Hedgehog and Wnt signaling (Davenport and Yoder, 2005; Singla and Reiter, 2006). These intriguing findings support a unifying hypothesis for the pathogenetic mechanisms related to primary cilia dysfunctions, that explain the multiorgan involvement and phenotypic variability observed in most ciliopathies.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: Italian Ministry of Health, MIUR, the March of Dimes, Burroughs Wellcome Fund NINDS, NIH. Contract grant number: Ricerca Corrente 2008 to BD; Ricerca Finalizzata 2006 ex art. 56 to EMV; Telethon grant n. GGP08145 to EB/EMV.

Footnotes

Communicated by Mark H. Paalman

INTERNATIONAL JSRD STUDY GROUP

Other members are: A. Zankl (Brisbane, Australia); R. Leventer (Parkville, Australia); P. Grattan-Smith (Sydney, Australia); A. Janecke (Innsbruck, Austria); M. D’Hooghe (Brugge, Belgium); Y. Sznajer (Bruxelles, Belgium); R. Van Coster (Ghent, Belgium); L. Demerleir (Brussels, Belgium); K. Dias, C. Moco, A. Moreira (Porto Alegre, Brazil); C. Ae Kim (Sao Paulo, Brazil); G. Maegawa (Toronto, Canada); D. Petkovic (Zagreb, Croatia); G.M.H. Abdel-Salam, A. Abdel-Aleem, M.S. Zaki (Cairo, Egypt); I. Marti, S. Quijano-Roy (Garches, France); S. Sigaudy (Marseille, France); P. de Lonlay, S. Romano (Paris, France); R. Touraine (St. Etienne, France); M. Koenig, C. Lagier-Tourenne, J. Messer (Strasbourg, France); P. Collignon (Toulon, France); N. Wolf (Heidelberg, Germany); H. Philippi (Mainz, Germany); S. Kitsiou Tzeli (Athens, Greece); S. Halldorsson, J. Johannsdottir, P. Ludvigsson (Reykjavik, Iceland); S. R. Phadke (Lucknow, India); V. Udani (Mumbay, India); B. Stuart (Dublin, Ireland); A. Magee (Belfast, Northern Ireland); D. Lev, M. Michelson (Holon, Israel); B. Ben-Zeev (Ramat-Gan, Israel); R. Fischetto, (Bari, Italy); F. Benedicenti, F. Stanzial (Bolzano, Italy); R. Borgatti (Bosisio Parini, Italy); P. Accorsi, S. Battaglia, L. Giordano, L. Pinelli (Brescia, Italy); L. Boccone (Cagliari, Italy); S. Bigoni, A. Ferlini (Ferrara, Italy); M.A. Donati (Florence, Italy); G. Caridi, M.T. Divizia, F. Faravelli, G. Ghiggeri, A. Pessagno (Genoa, Italy); S. Briuglia, G. Tortorella (Messina, Italy); A. Adami, P. Castorina, F. Lalatta, G. Marra, D. Riva, B. Scelsa, L. Spaccini, G. Uziel (Milan, Italy); E. Del Giudice (Napoli, Italy); A.M. Laverda, K. Ludwig, A. Permunian, A. Suppiej (Padova, Italy); C. Uggetti (Pavia, Italy); R. Battini (Pisa, Italy); M. Di Giacomo (Potenza, Italy); M.R. Cilio, M.L. Di Sabato, V. Leuzzi, P. Parisi (Rome, Italy); M. Pollazzon (Siena, Italy); M. Silengo (Torino, Italy); R. De Vescovi (Trieste, Italy); D. Greco, C. Romano (Troina, Italy); M. Cazzagon (Udine, Italy); A. Simonati (Verona, Italy); A.A. Al-Tawari, L. Bastaki, (Kuwait City, Kuwait); A. Mégarbané (Beirut, Lebanon); V. Sabolic Avramovska (Skopje, Macedonia); M.M. de Jong (Groningen, The Netherlands); P. Stromme (Oslo, Norway); R. Koul, A. Rajab (Muscat, Oman); M. Azam (Islamabad, Pakistan); C. Barbot (Oporto, Portugal); L. Martorell Sampol (Barcelona, Spain); B. Rodriguez (La Coruna, Spain); I. Pascual-Castroviejo (Madrid, Spain); S. Teber (Ankara, Turkey); B. Anlar, S. Comu, E. Karaca, H. Kayserili, A. Yüksel (Istanbul, Turkey); M. Akcakus (Kayseri, Turkey); L. Al Gazali, L. Sztriha (Al Ain, UAE); D. Nicholl (Birmingham, UK); C.G. Woods (Cambridge, UK); C. Bennett, J. Hurst, E. Sheridan (Leeds, UK); A. Barnicoat, R. Hennekam, M. Lees (London, UK); E. Blair (Oxford, UK); S. Bernes (Mesa, Arizona, US); H. Sanchez (Fremont, California, US); A.E. Clark (Laguna Niguel, California, US); E. DeMarco, C. Donahue, E. Sherr (San Francisco, California, US); J. Hahn, T.D. Sanger (Stanford California, US); T.E. Gallager (Manoa, Hawaii, US); W.B. Dobyns (Chicago, Illinois, US); C. Daugherty (Bangor, Maine, US); K.S. Krishnamoorthy, D. Sarco, C.A. Walsh (Boston, Massachusetts, US); T. McKanna (Grand Rapids, Michigan, US); J. Milisa (Albuquerque, New Mexico, US); W.K. Chung, D.C. De Vivo, H. Raynes, R. Schubert (New York, New York, US); A. Seward (Columbus, Ohio, US); D.G. Brooks (Philadephia, Pennsylvania, US); A. Goldstein (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, US); J. Caldwell, E. Finsecke (Tulsa, Oklahoma, US); B.L. Maria (Charleston, South Carolina, US), K. Holden (Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, US); R.P. Cruse (Houston, Texas, US); K.J. Swoboda, D. Viskochil (Salt Lake City, Utah, US).

References

- Baala L, Audollent S, Martinovic J, Ozilou C, Babron MC, Sivanandamoorthy S, Saunier S, Salomon R, Gonzales M, Rattenberry E, Esculpavit C, Toutain A, Moraine C, Parent P, Marcorelles P, Dauge MC, Roume J, Le MM, Meiner V, Meir K, Menez F, Beaufrere AM, Francannet C, Tantau J, Sinico M, Dumez Y, MacDonald F, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Gubler MC, Genin E, Johnson CA, Vekemans M, Encha-Razavi F, ttie-Bitach T. Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007a;81:170–179. doi: 10.1086/519494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baala L, Romano S, Khaddour R, Saunier S, Smith UM, Audollent S, Ozilou C, Faivre L, Laurent N, Foliguet B, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Salomon R, Encha-Razavi F, Gubler MC, Boddaert N, de LP, Johnson CA, Vekemans M, Antignac C, ttie-Bitach T. The Meckel-Gruber syndrome gene, MKS3, is mutated in Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007b;80:186–194. doi: 10.1086/510499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano JL, Leitch CC, Ansley SJ, May-Simera H, Lawson S, Lewis RA, Beales PL, Dietz HC, Fisher S, Katsanis N. Dissection of epistasis in oligogenic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature. 2006;439:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature04370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann C, Fliegauf M, Brüchle NO, Frank V, Olbrich H, Kirschner J, Schermer B, Schmedding I, Kispert A, Kränzlin B, Nürnberg G, Becker C, Grimm T, Girschick G, Lynch SA, Kelehan P, Senderek J, Neuhaus TJ, Stallmach T, Zentgraf H, Nürnberg P, Gretz N, Lo C, Lienkamp S, Schäfer T, Walz G, Benzing T, Zerres K, Omran H. Loss of nephrocystin-3 function can cause embryonic lethality, Meckel-Gruber-like syndrome, situs inversus, and renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:959–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consugar MB, Kubly VJ, Lager DJ, Hommerding CJ, Wong WC, Bakker E, Gattone VH, Torres VE, Breuning MH, Harris PC. Molecular diagnostics of Meckel-Gruber syndrome highlights phenotypic differences between MKS1 and MKS3. Hum Genet. 2007;121:591–599. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G, Vajro P, De Virgiliis S, Ciccimarra E, Boccone L, Pascotto A. Cerebellar vermis defect, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, and hepatic fibrocirrhosis without coloboma and renal abnormalities: report of three cases. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:180–185. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport JR, Yoder BK. An incredible decade for the primary cilium: a look at a once-forgotten organelle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F1159–F1169. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe HR, Smith UM, Cullinane AR, Gerrelli D, Cox P, Badano JL, Blair-Reid S, Sriram N, Katsanis N, Attie-Bitach T, Afford SC, Copp AJ, Kelly DA, Gull K, Johnson CA. The Meckel-Gruber Syndrome proteins MKS1 and meckelin interact and are required for primary cilium formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:173–186. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, Laclef C, Vierkotten J, Tory K, Golzio C, Lacoste T, Besse L, Ozilou C, Moutkine I, Hellman NE, Anselme I, Silbermann F, Vesque C, Gerhardt C, Rattenberry E, Wolf MT, Gubler MC, Martinovic J, Encha-Razavi F, Boddaert N, Gonzales M, Macher MA, Nivet H, Champion G, Bertheleme JP, Niaudet P, McDonald F, Hildebrandt F, Johnson CA, Vekemans M, Antignac C, Ruther U, Schneider-Maunoury S, ttie-Bitach T, Saunier S. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:875–881. doi: 10.1038/ng2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme “ductal plate malformation”. Hepatology. 1992;16:1069–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160434. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank V, den Hollander AI, Bruchle NO, Zonneveld MN, Nurnberg G, Becker C, Bois GD, Kendziorra H, Roosing S, Senderek J, Nurnberg P, Cremers FP, Zerres K, Bergmann C. Mutations of the CEP290 gene encoding a centrosomal protein cause Meckel-Gruber syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:45–52. doi: 10.1002/humu.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile M, Di Carlo A, Susca F, Gambotto A, Caruso ML, Panella C, Vajro P, Guanti G. COACH syndrome: report of two brothers with congenital hepatic fibrosis, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, ataxia, and mental retardation. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:514–520. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960823)64:3<514::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Keeler LC, Parisi MA, Marsh SE, Chance PF, Glass IA, Graham JM, Jr, Maria BL, Barkovich AJ, Dobyns WB. Molar tooth sign of the midbrain-hindbrain junction: occurrence in multiple distinct syndromes. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;125:125–134. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Evans CY, Williams MJ, Halford S, Gregory-Evans K. Ocular coloboma: a reassessment in the age of molecular neuroscience. J Med Genet. 2004;41:881–891. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.025494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefele J, Wolf MT, O’Toole JF, Otto EA, Schultheiss U, Deschenes G, Attanasio M, Utsch B, Antignac C, Hildebrandt F. Evidence of oligogenic inheritance in nephronophthisis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2789–2795. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AG, Rothman SJ, Hwang WS, Deckelbaum RJ. Hepatic fibrosis, polycystic kidney, colobomata and encephalopathy in siblings. Clin Genet. 1974;6:82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaddour R, Smith U, Baala L, Martinovic J, Clavering D, Shaffiq R, Ozilou C, Cullinane A, Kyttala M, Shalev S, Audollent S, d’Humieres C, Kadhom N, Esculpavit C, Viot G, Boone C, Oien C, Encha-Razavi F, Batman PA, Bennett CP, Woods CG, Roume J, Lyonnet S, Genin E, Le MM, Munnich A, Gubler MC, Cox P, MacDonald F, Vekemans M, Johnson CA, ttie-Bitach T. Spectrum of MKS1 and MKS3 mutations in Meckel syndrome: a genotype-phenotype correlation. Mutation in brief #960. Online. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:523–524. doi: 10.1002/humu.9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria BL, Hoang KB, Tusa RJ, Mancuso AA, Hamed LM, Quisling RG, Hove MT, Fennell EB, Booth-Jones M, Ringdahl DM, Yachnis AT, Creel G, Frerking B. “Joubert syndrome” revisited: key ocular motor signs with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:423–430. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich H, Fliegauf M, Hoefele J, Kispert A, Otto E, Volz A, Wolf MT, Sasmaz G, Trauer U, Reinhardt R, Sudbrak R, Antignac C, Gretz N, Walz G, Schermer B, Benzing T, Hildebrandt F, Omran H. Mutations in a novel gene, NPHP3, cause adolescent nephronophthisis, tapeto-retinal degeneration and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:455–459. doi: 10.1038/ng1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen R. The Meckel syndrome: clinicopathological findings in 67 patients. Am J Med Genet. 1984;18:671–689. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320180414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satran D, Pierpont ME, Dobyns WB. Cerebello-oculo-renal syndromes including Arima, Senior-Loken and COACH syndromes: more than just variants of Joubert syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:459–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi C, Adam S, Kahl P, Otto HF. Study of the malformation of ductal plate of the liver in Meckel syndrome and review of other syndromes presenting with this anomaly. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:568–583. doi: 10.1007/s100240010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla V, Reiter JF. The primary cilium as the cell’s antenna: signaling at a sensory organelle. Science. 2006;313:629–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1124534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith UM, Consugar M, Tee LJ, McKee BM, Maina EN, Whelan S, Morgan NV, Goranson E, Gissen P, Lilliquist S, Aligianis IA, Ward CJ, Pasha S, Punyashthiti R, Malik SS, Batman PA, Bennett CP, Woods CG, McKeown C, Bucourt M, Miller CA, Cox P, Algazali L, Trembath RC, Torres VE, Ttie-Bitach T, Kelly DA, Maher ER, Gattone VH, Harris PC, Johnson CA. The transmembrane protein meckelin (MKS3) is mutated in Meckel-Gruber syndrome and the wpk rat. Nat Genet. 2006;38:191–196. doi: 10.1038/ng1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, 3rd, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:591–597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente EM, Brancati F, Dallapiccola B. Genotypes and phenotypes of Joubert syndrome and related disorders. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk R, van Wesel AC, Thomas AA, Rijksen G, van Solinge WW. Ex vivo analysis of aberrant splicing induced by two donor site mutations in PKLR of a patient with severe pyruvate kinase deficiency. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verloes A, Lambotte C. Further delineation of a syndrome of cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis. Am J Med Genet. 1989;32:227–232. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320320217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]