Abstract

This article aims to provide understanding of how direct care workers (DCWs) in assisted living facilities (ALFs) interpret their relationships with residents and to identify factors that influence the development, maintenance, quality, and meaning of these relationships. Qualitative methods were used to study two ALFs (35 and 75 beds) sequentially over seven months. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 5 administrative staff and 38 DCWs and conducted 243 hours of participant observation during a total of 99 visits. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Results showed that the emotional aspect of caregiving provides meaning to DCWs through both the satisfaction inherent in relationships and through the effect of relationships on care outcomes. Within the context of the wider community and society, multiple individual- and facility-level factors influence DCW strategies to create and manage relationships and carry out care tasks and ultimately find meaning in their work. These meanings affect their job satisfaction and retention.

Keywords: Direct care workers, Assisted living, Staff-resident relationships, Meaning of care work

Paraprofessional workers have been termed the cornerstone of the formal long-term care system. Next to family and friends, they are the persons most involved in the hands-on care of increasing numbers of elderly and disabled people (Noelker, 2001). These direct care workers (DCWs) are predominantly female and increasingly non-white (Redfoot and Houser, 2005). For their work, typically described as onerous and physically and emotionally draining, they are paid among the lowest wages in America (Foner, 1994; GAO, 2001). Not surprisingly, the supply of these workers does not meet the growing demand for their services.

A considerable body of research addresses the critical staff shortages and high rates of turnover that plague the long-term care industry (Konetzka, Stearns, Konrad, Magaziner, & Zimmerman, 2005; Purk & Lindsay, 2006; Sikorska-Simmons, 2005). One fruitful area of interest focuses on the relationships that develop between DCWs and residents. Nursing home studies in fact indicate that satisfaction derived from affective ties with residents serves to counterbalance the more negative aspects of care work and improve worker retention (Berdes & Eckert, 2007; Foner, 1994; Monahan & Carthy, 1992). This paper addresses the nature and meaning of the relationships between DCWs and residents in assisted living facilities (ALFs), increasingly popular residential care settings often viewed as bridging the gap between home and nursing home. Similar to nursing homes, ALFs are experiencing growing problems with DCW shortages and turnover (Friedland, 2004; Galloro, 2001).

Assisted Living Facilities

Although ALFs vary from state to state in what they are called and how they are regulated and defined, for the most part they are non-medical, community-based settings that provide shelter, meals, and 24-hour protective oversight and personal care services to residents (Ball et al., 2000; Hawes, Rose, & Phillips, 1999). In 2004, ALFs numbered 36,451 with 937,601 units or beds (Mollica & Lamarche-Johnson, 2005). When defined broadly, ALFs encompass a wide range in size and type of facility and include small homes often categorized as board and care, as well as larger purpose-built models with private apartments (Mollica & Lamarche-Johnson, 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2001).

The limited data available about DCWs in ALFs indicate they have similar characteristics to DCWs in other long-term care settings (Potter, Churilla, & Smith, 2006). A national study of ALFs with more than 10 beds, in which approximately half of the sample of 569 workers were DCWs, found that assisted living (AL) staff members were mostly female (97%) and white (68%) (Hawes & Phillips, 2000). More than three-fourths of DCWs earned from $5 to $9 per hour, and most carried out a range of tasks in addition to personal care, including housekeeping, meal service, and medication assistance. Only 11% had completed any training prior to beginning work. The median ratio of direct-care staff to residents was 1:14.

Worker-Client Relationships in Long-Term Care

Long-term care research addressing social bonds between DCWs and the elders they care for indicates that these ties have importance for both caregiver and care recipient. In their ethnographic study of homebound elders, Ball and Whittington (1995) found that an elder's relationship with a home care worker could fill in for missing family ties and influence perceptions of care quality. Other home care studies (Eustis & Fischer, 1991; Piercy, 2000), as well as research in AL (Ball et al., 2000, 2005; Eckert, Zimmerman, & Morgan, 2001) and nursing homes (Bowers et al., 2000; Gass, 2004) also identify these relationships as key determinants of quality outcomes. Each of these studies indicates that for most dependent persons, quality care involves the emotional as well as physical realms and caters to personal needs and preferences, outcomes integrally tied to the nature of the caregiver-care receiver relationship.

From the caregiver perspective, nursing home studies show that DCWs achieve satisfaction from being needed and feeling emotionally close to residents (Foner, 1994), are most satisfied with aspects of their jobs that involve socializing with residents (Grieshaber, Allen, & Deering, 1995; Tellis Nayak & Tellis Nayak, 1989), are less likely to describe their job as stressful (Cantor, 1988) and stay longer (Monahan & Carthy, 1992) when they share emotional ties and believe that their relationships with residents are a central determinant of quality care (Berdes & Eckert, 2007; Bowers, Esmond, & Jacobson, 2000; Gass, 2004). Home care studies also have found the DCW's relationship with the client to be the most salient aspect of the job (Feldman, Sapienza, & Kane, 1990) and identified emotional attachment as the greatest reward for many workers and a deterrent of turnover (Karner, 1998).

Yet, research also makes clear that not all caregiving interactions are pleasant or have positive outcomes. Foner (1994) describes a nursing home environment where, despite evidence of close relationships, DCWs and residents often are in conflict, with racial differences magnifying the opposition. Other research reports racist behavior of white residents toward black DCWs and other forms of verbal and physical abuse (Berdes & Eckert, 2001, 2007; Foner, 1994; Jervis, 2001; Mercer, Heacock, & Beck, 2003). DCWs suffer emotional stress from interacting with residents who are in pain or dying (Berdes & Eckert, 2001) and when they lose a resident held dear (Black & Rubinstein, 2005), yet long-term care settings offer few supports for emotional labor (Foner, 1994; Moss, Rubinstein, & Black, 2003).

The existing long-term care literature indicates that relationships between dependent elders and their paid caregivers matter. How and why relationships matter is less clear. Moreover, no research has investigated DCW-resident relationships in AL. The purpose of this paper is to explore the quality and meaning of such relationships in the AL setting. More specifically, we examine the behaviors and personal perspectives of DCWs within the sociocultural context of AL to gain an in-depth understanding of how relationships with residents are developed and experienced. A primary goal of this research is to generate theory that can be used to improve the AL work environment and promote better care of residents.

Methods

This paper is based on a study of the role of workplace relationships in job satisfaction and retention of DCWs in ALFs. Although the study examined the range of DCWs' relationships in AL, including those with residents' family members, other DCWs, and administrators, this paper focuses on DCW-resident relationships. The goal of the study and this paper is to understand personal and cultural meaning, as well as significant processes operating in the setting, and we, thus, used a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

The study was set in two ALFs in Georgia, where ALFs are designated “personal care homes” and defined broadly to include a wide range of sizes and types. Georgia has 1,817 licensed ALFs with 27,086 beds (Unpublished data, 2006). AL regulations in Georgia require that persons who provide direct care to residents be at least 18 years of age and have current certification in emergency first aid and CPR and complete 16 hours of continuing education annually. The minimum staff-to-resident ratio is 1:15 in the daytime and 1:25 at night. National data indicate that Georgia resembles a majority of other states on minimum staffing levels, training requirements, job content, and pay (Hawes & Phillips, 2000; Mollica & Lamarche-Johnson, 2005).

For this study, we purposively selected two ALFs that differed in size and ownership since previous AL research suggests that these factors have bearing on DCW relationships (Ball et al., 2000, 2004, 2005; Morgan, Eckert, & Lyon, 1995). Blue Castle had 35 residents and 23 DCWs, was independently owned, non-profit, and housed on the sixth floor of a retirement home. Forest Manor, a purpose-built, 3-story, free-standing ALF with 75 residents and 38 DCWs and a separate dementia care unit (DCU), was owned by a small, for-profit corporation. Fees at both homes were paid privately by residents and ranged from $2,850 to $3,900 at Blue Castle and $2,500 to $5,300 at Forest Manor.

Because attitudes and experiences of DCWs are influenced by their own race and ethnicity and by whether they have similar or different racial and ethnic backgrounds from residents (Foner, 1994), we selected ALFs where the race of staff and residents varied. In both ALFs, the large majority (95%) of DCWs were black. Only one resident (in Forest Manor) was black. To better understand how workplace relationships affect DCW retention, we also selected ALFs with a reputation for high retention. The mean employment tenure at Blue Castle was four years (with a range of 2 months to 10.5 years) and at Forest Manor, six (with a range of 3 months to 14 years). In addition, we wanted homes that had been open long enough to examine relationships over time. Blue Castle had been operating for 11 years and Forest Manor for 20.

During the first month in each ALF, we interviewed the executive director and resident services director, who supervised care staff, in order to orient researchers to the facilities and gain understanding of policies and procedures regarding staff experiences and relationships. Blue Castle had only these upper-level management positions, whereas Forest Manor also had a business manager, a director of marketing, and directors of activities for both the AL floors and the DCU. We interviewed the activity director for the DCU because he worked closely with the DCWs.

We used purposive maximum variation sampling (Patton, 2002) to guide initial selections of DCWs for in-depth interviews based on differences in tenure, shift, full- or part-time status, education, race, ethnicity, and job content. All DCWs were female. Each home had a shift supervisor position with responsibility for medication assistance, and we selected both types of care staff. Theoretical sampling guided subsequent selections. The final DCW sample included approximately half of the DCWs at Blue Castle (10) and three-fourths at Forest Manor (28). Table 1 describes the characteristics of DCWs interviewed.

Table 1. Characteristics of Direct Care Worker Participants.

| Variable | % (N=38) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 18-44 | 37 |

| 45-64 | 60 |

| 65-74 | 3 |

| Race or Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | 8 |

| African American | 90 |

| African Caribbean | 2 |

| Education Level | |

| Less than high school | 10 |

| High school degree | 53 |

| Some college | 32 |

| College degree | 5 |

| CNA training | 42 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 31 |

| Divorced | 21 |

| Widowed | 11 |

| Single | 37 |

| Years employed facility | |

| M (SD) | 6 (4.52) |

| Range | 2 mos.- 14 yrs. |

Data Collection

We collected data using participant observation and in-depth and informal interviewing for a period of three months in Blue Castle and four in Forest Manor, with a one-month interval for data management and analysis. Our strategy of sequential study permitted all researchers to study both homes, adding to data credibility.

We conducted participant observation at both sites during visits on all days of the week during day and evening hours to observe a range of DCW experiences, for a total of 243 hours and 99 visits. We observed routine DCW tasks, such as meal service, housekeeping, medication assistance, and grooming, as well as any special events, focusing on the actions of DCWs and their interactions with residents. Our participation in facility activities included assisting with meals and activities and accompanying residents and staff on outings. The following description of the initial interaction between one researcher and two care staff at Blue Castle shows how such assistance helped build rapport with our informants:

The supervisor asked me [the researcher] to walk with her to the dining room where Elaine and Shonda, the caretakers for that shift, were working. She introduced me to them and said, ‘Marilyn will be sort of following you to watch and observe.’ They smiled and said, ‘Well this is what we do,’ and they continued to unload the dishwasher. Elaine smiled a lot and wanted me to feel comfortable, but Shonda appeared to be not interested in who I was and quietly doing her work. I decided to now break the ice and start a general conversation. So I asked Elaine (who was wiping the dishes dry) if I could help? Oh my God, you should have seen the smile on both their faces. So I thought this was my trump card to get friendly with them, so I quickly took a paper towel and started drying the forks, spoons, and knives. Now Shonda decided to find out who I was and exactly what my study was about. She was very happy to talk, and then we talked about several different things. We talked about jobs in general and then about education and then children. God knows how the conversation went into teen pregnancy.

This same researcher “broke the ice” at Forest Manor when she invited all of the DCU residents to her home for afternoon tea.

During observations, as the above passage shows, we interviewed DCWs informally, which added depth of understanding to observational data and allowed us to clarify and augment data from in-depth interviews. We recorded all observations and informal interviews through detailed field notes, which became part of the overall qualitative database.

In-depth DCW interviews were open-ended and addressed a wide range of topics, including work histories, work routines, social relationships, attitudes toward work and individuals in the work setting, and personal characteristics. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

We used a three-level grounded theory coding process (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to analyze data pertaining to staff-resident relationships. In the first stage, known as open coding, we examined all data line-by-line for emergent categories based on our research questions and issues raised by the participants. Examples of initial codes included: work strategies, resident encounters, trust, job frustrations, and care roles. We then developed codes in terms of their properties (e.g., type, intensity) and dimensions (e.g., frequency) and applied them to our data. For example, we identified two broad types of strategies—for providing care and developing and managing relationships—from which we developed sub-categories (e.g., trying again later, showing affection, minimizing contact). In the second stage, axial coding, we linked initial categories to other categories in a set of relationships indicating causal conditions, context, intervening conditions, strategies, and consequences, termed a paradigm (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). For example, we linked strategies to individual- and facility-level factors such as residents' functional status and race, DCW training and personality, and facility workload. We then integrated and refined categories to form a larger conceptual scheme through selective coding—in which we organized our major categories (strategies, relationship type, care outcomes) around our central explanatory concept or core category (Strauss & Corbin, 1998)—“creating meaning through relationships.” Analysis was considered complete when theoretical saturation occurred. We used a software package (Ethnograph 5.0) to facilitate data management and analysis.

Findings

For most DCWs, their relationships with residents are a primary, for some the primary, component of job satisfaction. When asked what they liked best about their jobs as a whole, a majority (63%) named caring for and relating to residents. Even those who named other aspects as most satisfying made it clear that interactions and relationships with residents contribute to job satisfaction. Moreover, slightly over a third indicated “the residents” were a central factor in their decision to remain in their jobs. It is through their relationships with residents that care workers find meaning in these low-status jobs that offer few tangible rewards. As one said, “They are the reason I come to work.”

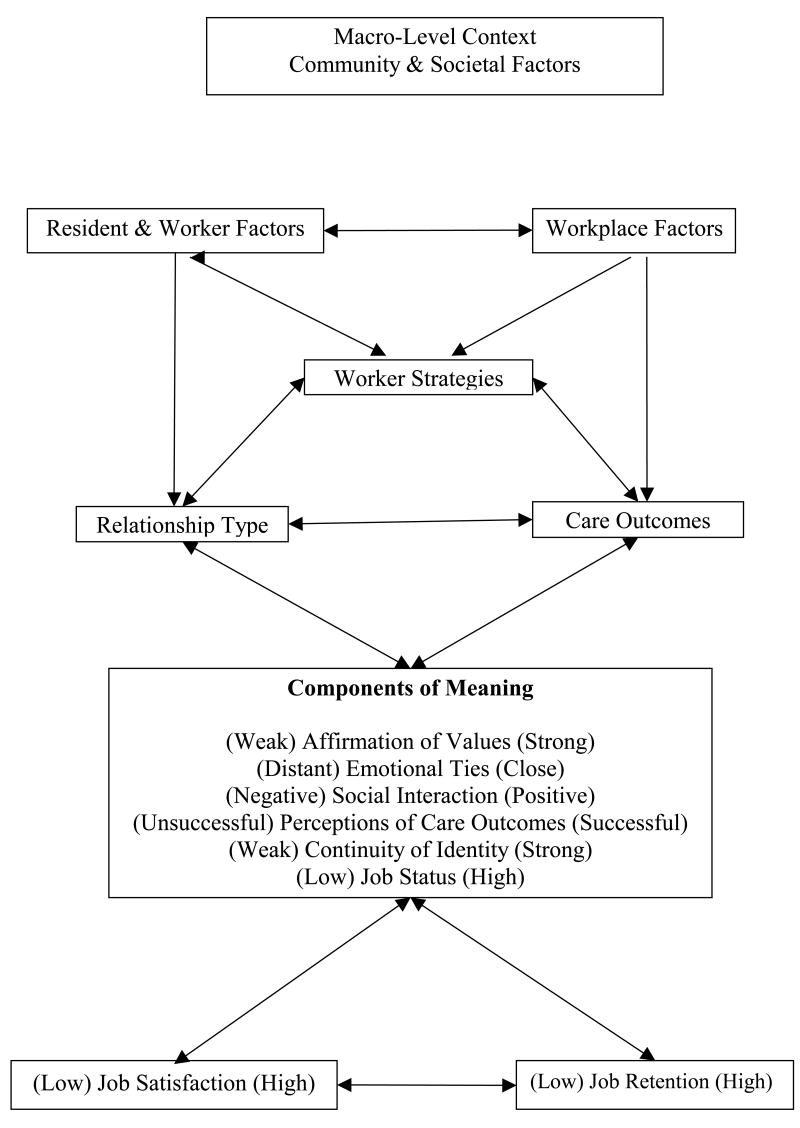

Our conceptual model (Figure 1) based on our grounded theory analysis depicts the process of creating meaning through relationships. In this model, macro-level community and societal factors provide the context for the process. Community-level factors, such as unskilled job opportunities, local wages, ALF competition to fill beds and hire quality staff, and availability of public AL funding, affect factors such as DCWs' employment motives, retention decisions, and attitudes toward residents and facility wages and benefits, staffing policies, and resident profiles. Societal forces of racism, sexism, ageism, and the low value placed on care work influence DCWs directly and indirectly through community-level factors. These factors join with workplace and personal factors to limit workers' career options and color their work experiences and the meanings these experiences hold. Despite the common viewpoint that it is difficult to stay in this job only for the paycheck, at the core of most decisions to stay was the need to have a job and the belief that this job, albeit low-paying, offered the best employment option. Another worker said, “I think what is going to keep me here is that I do have a job.” In addition, 43% of the DCWs interviewed had another job.

Figure 1. Creation of Meaning.

Within the context of the wider community and society, multiple resident and worker factors interact with workplace factors to influence directly and indirectly the other elements in the model—worker strategies, relationship type, care outcomes, meaning components, and, ultimately, job satisfaction and retention—all of which, in turn, are dynamic and interactive. Our discussion of the various components and linkages laid out in the model addresses first the individual- and facility-level factors we found to be most influential.

DCW and Resident Factors

The principal factors pertaining to DCWs included personal characteristics and values, family and employment histories, and work-related training. Most DCWs in these two homes accounted for positive relationships with residents in terms of their own special traits and values. Myra at Forest Manor was typical: “I am a nice person. I get along with elderly people more than I get along with people in general. I can understand where they are coming from and where they are going and the kind of care they need.” Blue Castle worker, Elaine, said: “You have to be a good strong person. Older people are either making some kind or noise or they drool. A lot of them [co-workers] can't stand that. It don't bother me.” Other qualities deemed essential included patience, altruism, friendliness, and, in the words of one, “the spirit in me.” Most DCWs also espoused a value for helping elders. As one said, “I like people and helping people, especially older people, because once they get a certain age people don't seem to want to be bothered with them. They need someone to be there with them, and I like that.” This value for helping was identified as a strong motivation for entering and remaining in the field of caregiving. Diane, at Blue Castle for over 16 years, provides an example: “Before I worked in nursing homes I was a cashier. Over the years I realized that something was just missing. I couldn't put my hand on it. I had a friend ask me to come and fill out an application at a nursing home. When I went to a nursing home I found out that that was what it was, taking care of people who could no longer take care of themselves. I have always cared about people. I have always had a big heart.”

Frequently, values for helping elders and caregiving jobs stemmed from past family experiences, such as caring for a parent, living with grandparents, or having a relative who worked in long-term care. Valerie, a Blue Castle worker, said, “The reason I did it [chose this type of work], because when I was younger my grandfather was really sick and I always helped out with him, both of my grandparents, because my great-grandmother lived until she was 106. She just died last year. I like helping the elderly.” Workers also accounted for close relationships with residents in terms of such former ties. Sherry explained: “Probably my love of people and older people. That is what it is. We can talk about anything, like making soap. I am from the country. Being from a small town and being raised by grandparents, I communicate with them better than I do with regular or normal younger people. I remember all the old sayings. It is fun.” Sherry's childhood experiences contributed to her interpersonal skills, which, together with her over 15 years of formal caregiving, influenced her ability to negotiate relationships and provide care, as well as the meanings these relationships held. Over half of workers had prior experience working in other ALFs or nursing homes.

The personal characteristics and values of residents, as well their past history, functional status, family support, and facility tenure, also influenced the process of meaning creation. In both homes, certain residents were universally loved. One worker described Isabel, a favorite resident in the DCU at Forest Manor: “She is so sweet. Isabel is everybody's heart up here. She is so funny and comical. She just makes your day.” Isabel's popularity stemmed from her pleasing personality, as well as her appreciative, respectful, and compliant manner. Other residents had attributes less conducive to relationship building. As one DCW said, “Some are nice and some have that snap-back personality.” Carole sometimes resorted to kicking, biting, and verbal abuse and was described as “mean and nasty.” DCWs attributed Carole's “meanness” to dementia, which had developed over her years at Blue Castle. Workers who had known Carole in prior years coped better with her abusive behaviors.

The influence of a resident's functional status was variable. Because DCWs typically spent more time providing care to less functional residents, when interactions were positive (usually when residents were compliant and appreciative), closer relationships developed. Less needy residents sometimes resisted interaction and relationships. As one worker said, “Some of them won't open up at all. They are like, ‘Get the trash and go.’” In addition, a resident's frustration because of dependency or the effects of dementia or other health problems, such as the inability to communicate or combative behaviors, influenced strategies and typically impeded both relationship development and care provision. The following passage from field notes in the Forest Manor DCU shows the importance of DCW patience in caring for residents with dementia:

Sarah and a resident talk about hair. The resident wanted to see how long Sarah's hair was, so Sarah shows it to her. Sarah is a very patient listener. She does not interrupt the residents and finish their sentences for them when they begin to talk to her. She just stands and listens to them completely and then answers them. Sometimes it takes a whole five minutes for someone just to ask for water, or say something very very simple.

The care roles of residents' family members, as well as their attitudes and behaviors toward DCWs, also were influential. Workers often got closer to residents without family support, even assuming traditional family roles. Family members generally facilitated care processes and relationships by providing information about residents' histories and preference and showing appreciation for DCW care roles. Similar to residents, some relatives were kind and considerate and others were rude and demanding, and these behaviors could either promote or hinder their own and residents' relationships with DCWs. The following field note excerpt from Forest Manor's DCU illustrates one family member's viewpoint:

Irene's daughter said she thinks the 3rd floor staff are very good. She said, “Of, course, some are more attentive than others, but that is probably due to personality.” She mentioned April as being her mother's favorite and her favorite. She said April always talks to her mother and spends time with her.

In one case, a resident's attempt to shield a favorite worker from her son's abusive treatment, including attempts to have her terminated, further cemented the resident-DCW bond.

In both ALFs, racist attitudes and behaviors of white residents toward black staff altered strategies, relationships, and care outcomes. When asked about the effect of race, one DCW replied: “Race, man, yeah, throughout the whole building, it's nothing but Caucasian people that live here. The only people that work here are African American. So, you know, that ought to say something about this facility.” Racial slurs used by residents included “colored girl” and the “n-word.” Ethnic differences created further problems. The heavy accents of two Blue Castle DCWs from the Caribbean hindered communication and created distrust, ultimately affecting relationships and care provision.

As in many ALFs, all DCWs and the majority of residents were female. In most cases, being female facilitated relationships, but with male residents it could create barriers. Myra related her experience: “I think he wanted a man to wash his body. When you went to wash his important parts, he didn't like that. I told him one day that there was nothing but ladies and ‘you are going to have to let me do this for you.’ He had his pride. You can understand that.” When showing affection to men, female workers also had to take special care not to give the perception of impropriety. Carla described her strategy: “I am careful that no one gives any sexual connotations to us giving him a hug. It is just a hug, a loving response to this man.”

Workplace Factors

A variety of workplace factors influenced DCW strategies, relationships, and care outcomes. The physical environment was one. Because Blue Castle was smaller and situated on one floor, DCWs were in regular contact with all residents. Interaction was further promoted by the location of a DCW work station in the home's main common area, where residents routinely gathered. The DCU at Forest Manor, which occupied the third-floor, was similarly conducive. Joanne explained: “It is more intimate. You are working without a whole lot of people. Up here you are contained. It is like it is one-on-one.” Forest Manor DCWs assigned to the two floors of the AL section had fewer opportunities to interact with residents, particularly the more functional ones.

Hiring practices in these two ALFs emphasized DCWs' emotional capacity to care about residents over their physical caregiving skills and knowledge. The director at Blue Castle was clear in her preferences: “I am looking for a person who is truly a caring kind of person, having a heart for the job and a heart for people. I can teach you to be a good waitress, but I can't teach you to have a heart.” The resident services director at Forest Manor expressed a similar strategy: “You need people who are going to come in and be compassionate to them no matter what they say to them. That is the most important thing.”

Administrative policies and procedures at both ALFs were supportive of close relationships. Administrators encouraged DCWs to spend social time with residents and authorized workloads and staffing ratios that accommodated relationship building. Forest Manor's director, Betty, believed the practice of allowing DCWs to be on first-name basis with residents contributed to a family-like atmosphere. Permitting staff to work privately as sitters for residents (not allowed at Blue Castle) promoted bonding, and a flexible policy regarding resident assignments accommodated both the idiosyncratic nature of relationships and difficult resident behaviors. Neither director tolerated resident abuse of DCWs, although they too made allowances for dementia. Both facilities had discharged residents for abusing staff, “even if it meant an empty bed.”

The DCW job at both homes included an array of tasks, including meal service, housekeeping, and recreational activities, in addition to assistance with activities of daily living. Blue Castle had shift supervisors, whose primary responsibility was to assist residents with medications, although they provided ADL care when needed. Forest Manor also had one staff person assigned to medications, in addition to lead caregivers on each shift. The nature of DCW-resident interactions, as well as the quality of relationships, often varied according to the type of task involved. Although hands-on care could entail significant problems, especially when residents resisted care, the more personal nature of the work and lengthier time span of the encounter contributed to relationship building. Kim described her “bonding” experience: “Last weekend I shaved him, and he said I did a good job. I had never shaved a man before. I enjoyed it because we had never bonded before and I felt we bonded.” One shift supervisor at Blue Castle also provided nail care to residents, which afforded her unhurried and conflict-free opportunities for interaction with residents. In contrast, meal service, which cast workers in a more servant-like role vis-à-vis residents, frequently engendered negative encounters. Myra explained: “I can work with the residents as far as going to their room and getting their trash at night. All of them get along with me. In the dining room, it is a problem. They are like, ‘You are too slow,’ or, ‘Are you new?’ They get snobbish with their comments, but that is part of your job. You take it as it comes.” Betty, Forest Manor's director, demonstrated empathy for both residents and DCWs: “Their lives revolve around the three meals. If you put cornbread on there and they asked for a dinner roll, they are going to let you know it in no uncertain terms. We tell them that is one of the hardest parts of their job, the people who work in the dining room.” Housekeeping tasks generally were not satisfying to workers and diverted them from the more valued relationship building.

DCWs at both homes rarely complained about being pressed to finish their assigned tasks, and many described their work as “easy.” The heaviest care residents were in Forest Manor's DCU, which was staffed accordingly, including the use of personal sitters. Workers valued their reasonable workloads, and almost all emphasized the importance of time as a requisite for forming relationships and good care outcomes. Sally compared Forest Manor to the nursing home she left 14 years ago: “Here, you have more time to build the relationship. I am not running. I have time to say good morning and talk to them. That is what counts.” Kim explained how spending time with cognitively impaired residents was especially critical: “If you take the time and sit with them and talk to them, they know a lot more than people give them credit. Some of them have mean expressions on their face and you think they are mean, but they are the sweetest people.” Time also was considered essential to forging trust, a key component of relationships and care provision, as one DCW explained: “Say you are giving them a bath and you are rushing, they are not going to want to take it. If you sit and talk with them for a minute, it makes them feel more trusting. That is important to have someone to trust you. I deal with them everyday and I want them to trust me.”

DCWs deemed long-term association also critical to “learning” residents. A worker of 11 years, said: “After a while you learn them. You know what they need and what they don't, if they can get up right away or if they need to sit on the bed for a while before they get up. It is time working with them one-on-one, what you have experienced from the past. Each resident needs care in their own way.”

As the model shows, DCW and resident factors can interact with workplace factors. For example, retention decisions and resident decline affected workload policies; admission and hiring policies and fee level influenced resident and worker profiles.

Relationship Type

The type of relationship that developed between DCWs and residents was influenced by the multiple factors discussed above, as well as by worker strategies and care outcomes. Specific relationships ran the gamut from loving to downright hostile, but almost all DCWs had close emotional bonds with at least one resident, typically more. Some considered such bonding inevitable. One long-term worker said, “I know you say we don't need to get attached to people, but trust me, you do get attached.” From another, “I know I fall in love with some of the residents. It goes without saying that you are going to fall for some of them really hard.” Having favorites or “pets” was common.

Workers characterized close ties with residents as both friend- and family-like. Sandra, at Forest Manor for three years, described the evolution of one friendship: “I remember the day she came in. I was in the dining room and my cousin said I was going to like her. I started going in her room and talking to her. We became best friends, and I would go and push her around [in her wheel chair] and stuff. One night I went to her room and she held my hand and said, ‘You are my best friend. I said, ‘You are my best friend.’” Another worker, Eunice, said, “They [residents] become a part of my family.

Although we did not conduct in-depth interviews with residents, we talked with some informally and observed their interactions with staff. The following field note excerpt portrays the reciprocity of close relationships:

Bud, one of the male residents who does not participate in any activities and stays in his room, except for meals, had a nice exchange with Sally. After breakfast, Sally told him he had to lose a little weight. She patted his stomach and asked if his feet were still swollen. He showed her. His ankles were swollen but not as bad as they had been. She asked him what he is supposed to weigh. He said, “190.” She shook her head and said he is over 200 pounds now and he has to stop picking up that salt shaker. Bud told Sally he loves her, and she hugged him and told him he could not get along without her. Bud, said, “You are right, I love you and I'm from the South.” I guess he was referring to the fact that Sally is African American. They both laughed and he told Sally to come and weigh him later and see how much he has to lose.

Because of differences in race, class, and culture, most DCWs and residents came from mismatched worlds. Finding commonalities across these differences helped establish relationships. Sherry, who grew up in the “country,” remembered “the old sayings.” Susan liked talking to one resident who shared her Christian beliefs. Ava, older and college educated, connected to a resident with mutual interests in books and classical music, and Carla's love of dogs led to a special friendship with Elizabeth Allen, who referred to Carla as her “buddy.” The following passage from field notes characterizes their close and long-term relationship: “Carla and Elizabeth Allen know so much about each other. They know about each other's drug use and history, liquor preferences, kids' interests etc. I am surprised both about the amount that Carla and Elizabeth have shared with each other, as well as the extent of their memories about these things. I sit and listen to them both telling me about their knowledge of one another and telling each other stories as reminiscence.”

Often it took a particular combination of worker and resident for close relationships and successful care outcomes. DCWs frequently talked about whether they “clicked” with a particular resident. Nina described one of her triumphs: “Yes, he hadn't been here that long, but we clicked. I was the only one who could give him a shower. He was very private and independent. He didn't want anyone waiting on him for anything. He did let me give him his showers. We got close. That was my friend.” Nina's ability to succeed as both friend and caregiver evolved during the process of care and was based on her ability to empathize with the resident and respond in an appropriate way.

Worker Strategies

In essence, DCWs employed two types of strategies in their jobs—those to develop and manage relationships and those to provide care. Because DCWs believed their work involved both physical and emotional care, typically relationship and care strategies complemented one another or were one in the same. Strategy choice was influenced by DCW, resident, and workplace factors, the type and length of the relationship, and the unique care situation. The following excerpt from field notes again shows Sarah's usual manner:

I noticed through the time I was there today the way different staff interact with residents. Sarah always comments on how residents look. To one woman she said, “You are a very pretty woman.” She patted her hair and told her she looked so good that day. Sarah is very “hands on” with residents, meaning she hugs and touches them.

Getting to know residents was fundamental to relationship building and care provision. Myra expressed it well: “I know each and every one of them and what they will and won't do. I think that is a plus. A lot of people have been here a while, and they still don't know what this person might want or need. I just took it upon myself and got to know each and every resident one by one. My mother went through Alzheimer and I sat at home and took care of her. I would treat them the same way I treated my own mother before she passed.” Myra's strategy depended on her own values, skills, and experiences, a resident's willingness and ability to reciprocate, and a reasonable workload.

Other situations required alternative strategies, such as minimizing contact, trying again later, and joining forces with or relinquishing responsibility to another staff person. Carla described her course of action in dealing with rude residents: “There is a certain way to talk to me. You don't have to be all sweet and honey, but if you talk down to me, you might not get what you want or you will get what you want in a certain way. It will be straight and to the point. I am not going to be mean to you, but I will give you your pills and water and I am not going to spend a lot of time and conversation with you.” Carla's strategy involved not only caring and relating but protecting her sense of self.

Although some workers minimized the intent and effect of racism, most considered it inherent in the job and just learned “to deal with it.” With time, some DCWs became hardened to insults. When asked whether race had affected her relationships with residents, Carla replied: “At times, when they throw out the n-word. I have been in this field so long I don't get upset and irate like some staff have.” By and large, workers attributed racism to residents' historical experience in the South, referring to them as being “still trapped back in those days.” Whether or not workers considered residents responsible for their actions influenced their response and the nature of the subsequent relationship. Most excused racism from residents with dementia, as Carla explained: “When Carole calls us the n-word, it is just Carole. She may not have said it 10 years ago, but she says it now. I am not going to say she is responsible for what she says now.” DCWs typically chose different strategies for residents “with a good mind.” One explained, “Well, we did have one lady and she was kind of racist, and she would call you a name. That is the one I would go stand outside [her room].”

Most DCWs experienced grief associated with the death of residents, often compared to the loss of a family member and described by one as, “Like someone just snatched my heart out and it wasn't there anymore.” Although a commonly held viewpoint was that emotional bonding often was unavoidable, some workers attempted to shield themselves from potential pain. Alice, a longtime worker described her strategy: “As the years go on, you leave a space open in your heart that these things happen. You get up in age like that, you can walk away from a resident, and the next hour they could be passed away. I leave a space open in my heart to accept that.” Strategies like Alice's are designed to protect DCWs from the more costly aspects of their work, including negative attacks on the self. Thus, Carla limited interaction with the resident who “talked down” to her, and another DCW chose not to cross the threshold of the racist resident. Rationalizing residents' racism represented another means of maintaining a positive sense of self, as did advancing themselves as having special traits that equipped them for this demanding work.

Care Outcomes

Care outcomes in our conceptual model refer to whether or not a worker is able to carry out an assigned task, as well as her perception of the impact of the care process on the resident. Care outcomes are influenced by, and in turn influence, relationships and strategies. Outcomes also are influenced directly and indirectly by DCW, resident, and workplace factors. The following passage from field notes describes Elaine's attempt to give a bath to Carole, the difficult Blue Castle resident described earlier:

Elaine went to wash Carole and Carole said, ‘I don't hear you, and I don't want you to talk to me. Leave me alone and leave now.’ So Elaine smiled and said, ‘Why? You don't want me around?’ and Carole said, ‘Yes. Don't you hear me? Leave right now.’ Elaine asked Carole if she had a shower and washed her dentures, and Carole said, ‘You don't tell me what to do and how to do it. I'll do stuff when I want to. I don't even want to be here.’ And she closed her eyes again. Elaine said we will have to leave the room as she was hostile, and she would not be cooperative.

Because of her long-term relationship with Carole, Elaine knew that attempting to bathe Carole at this time would be fruitless. Care outcomes were much different with another resident, Mrs. Dunn, who had recently returned from the hospital:

Mrs. Dunn was lying down in bed and as soon as she heard Elaine shouting, “Hello, Mrs. Dunn, how are you?” Mrs. Dunn smiled and said, “I am so glad to be back home.” Elaine then said, “We sure are glad to have you back.” Elaine told Mrs. Dunn that she missed her. Elaine then went to touch Mrs. Dunn and asked Mrs. Dunn if she would like to have a shower. Mrs. Dunn readily agreed and said that she definitely would love one. So Elaine immediately undressed Mrs. Dunn and helped her into the bathroom and gave her shower. While giving her the shower they talked about Mrs. Dunn's stay in the hospital and how she was now feeling. While chatting, Elaine reminded Mrs. Dunn to use the wash cloth to wash herself. Elaine washed Mrs. Dunn's back. After the shower, Elaine asked Mrs. Dunn if she would like her to put some skin cream on her back as it seemed dry. Mrs. Dunn agreed and Elaine applied some cream. Elaine then helped Mrs. Dunn dress in a clean gown and took the old clothes and put them in the laundry. Elaine then asked Mrs. Dunn to rest and promised her that she would come back again to take the breakfast tray from the table. Mrs. Dunn thanked Elaine and went to lie down on her bed.

Most DCWs admitted to spending more time with or performing “extra” services for their “pets.” However, less positive relationships did not cause workers to shirk their duties. When we asked DCWs how their relationship with residents affected how they gave care, a typical response was: “I do my job regardless. I am here to take care of them, and I will do it no matter.”

Creating Meaning

In our conceptual model, creation of meaning is a process that unfolds over time. As shown in Figure 1, the meaning that relationships with residents holds for DCWs involves multiple components, which relate to affirmation of lifelong values, nature of affective ties and interactions with residents, continuity of caregiver identity, perception of the care provided and job status. Components have variable properties and dimensions. For example, affirmation of values varies from weak to strong and affective ties from distant to close.

For many DCWs, the meaning of their relationships with residents was rooted in the past. They came to this job with expectations and values, which colored both the meaning and enactment of their caregiving roles. Thus, Sherry, who had been raised by her grandparents in the rural South, enjoyed talking to residents about the past and could relate to them and their life experiences. Similar encounters conveyed alternative interpretations based on the uniqueness of participants. Kim, whose grandparents were deceased, appreciated her time with residents because they could “fill in” where her “grandparents would have been.”

Meanings continued to emerge as workers went about their jobs interacting with and caring for residents. They derived satisfaction when their values for loving and helping elders were validated. As Myra said, “It makes me feel good if I can make one of them feel better.” As Myra's words indicate, emotional sustenance often was reciprocal. For Elaine, “Seeing the residents smile and listening to them say, ‘I love you, Elaine. I love what you do for me,’” made Elaine “really feel good,” as though she were “on cloud nine.” For some of these women, the love they received from the residents was the one bright spot in their otherwise stress-filled lives. Lois, an older widow, said: “They give me plenty of love, and I thank God for sending me to this place because it is really what I needed. They add so much to my life and keep me from being lonely.” Some believed their rewards would be bestowed in the future either on them or a loved one in need of care. In Kim's words, “I feel the nicer I am to them, the better I will be treated when I get there.” Most workers also derived satisfaction from their conversations with residents, hearing the “stories” about their past lives, often far removed from their own experiences. Sherry explained, “The conversations we have and knowing about their history and where they came from, it impresses me. They have been through wars and all sorts of things. Oh my God, it is amazing what they have gone through. That is my history right there. It is interesting.”

But, as one worker said, “It is not all cake everyday,” and less positive interactions and outcomes led to different meanings. What many workers found most frustrating was residents who “don't want to do nothing you want them to do” or “nothing you do makes them happy.” In such cases, frustration came from their inability to accomplish the necessary tasks and make residents “feel better” and, thus, affirm their caregiving roles.

Some DCWs actively sought and found a sense of continuity of identity through their roles in elder care. Elaine, now aged 62 and at Blue Castle for nine years, provides an example of this process. Elaine was raised by her grandmother in South Georgia, and one of her first jobs was taking care of “lady who couldn't move around too good.” Later, with only an 11th-grade education, she moved to Atlanta and worked in a textile mill and then as a cook, before quitting to care for an elderly uncle. After the death of her uncle she began working at Blue Castle. The passage below shows the influence of a lifetime of experience and values on how Elaine defines her continuous self:

I didn't have a whole lot of training. It is basically taking care of people, which I love to do. I always have loved to help with them. I feel like if you love older people and love working with them, I think that is love and I think you will do what you think is best for that person. That is me. All the people know that. Throughout the building, I cut up. I dance and sing. Sometimes when I do that, it makes me feel good because it makes them feel good. When they are laughing, it takes their mind off of their pain or their problems. We are trying to have a good time. I love my work and I love this job. Not only this job, but I take it farther, because if I see someone who needs my help I will help them. That is just me.

Although Elaine was frustrated by her low pay (now $8.25 per hour), she planned to stay at Blue Castle until age 70. When asked what most kept her there, her reply reiterated her desire to seek a consistent and valued identity in her work: “I think it is caring of the resident. I care for people and I love working, no matter what I am doing. To me, I don't see nothing wrong with it. I don't mind doing it. I will sing and whistle.”

As Elaine's example shows, the meanings workers attached to their relationships with residents and their role-identities as elder careworkers also are influenced by their positions in their communities and society at large. That society attributes little value to them and their work is manifested in the low material rewards they receive. Finding themselves in this situation of needing to stay in a low-status job, some DCWs sought to elevate the status of their jobs, and themselves, by minimizing the importance of low wages, while at the same time emphasizing the value of care work and the qualities they possessed to perform it. Sandra expressed a recurring theme, “You have to care. You have to love elderly people for one thing. That is the only way you can do this job because you can't do it [just] for money.” To Ella and others there is “nothing wrong” with that.

Discussion

This research sheds light on relationships between direct care workers in AL and the residents they care for and the effect of these relationships on their job satisfaction and retention. We found that a variety of macro-level factors provided the context for the process of creating meaning through relationships. Multiple DCW and resident factors influenced: the type of DCW-resident relationships; the strategies DCWs used to manage relationships and provide care; care outcomes; and the ultimate components of meaning. Strategies, relationship types, care outcomes, and meanings were dynamic and interactive. Whether relationships with residents led to job satisfaction and retention depended on the degree to which workers were able to affirm their values for helping elders, develop close affective ties, engage in positive social interactions, complete necessary care tasks and improve residents' quality of life, maintain a continuous identity, and redefine their job status. The influence of particular components varied across workers.

Our findings make clear that the development of relationships between DCWs and residents in AL is a dynamic process intimately linked to giving care. Relationships both emerged through and enabled the caregiving process. Because of the fine line between caring and caretaking, the existence of close affective bonds in the formal care arena is not surprising. Care is delivered in the context of a “human dyad” (Abel, 1995), and, as Karner (1998) so aptly states, emotional ties “spring from the nature of caregiving.” Hochschild (1983) coined the term “emotional labor” for the social component of caregiving work. In her conceptualization, caregivers are expected to perform emotional labor even if their true feelings would have them do otherwise. Our findings show that caregivers did in fact “manage” their hearts when dealing with difficult residents, though they did have strategies to minimize contact with such residents.

In many cases, workers in our study characterized relationships as evolving to the level of fictive kin. Residents became “like” their parents and grandparents. In her study of homecare workers, Karner (1998) describes a similar process, in which the relationships between workers and their elderly clients progressed from task-oriented, to friendship, and, finally, to familial adoption. Substantiating research in nursing homes (Berdes & Eckert, 2007; Bowers et al., 2000; Foner, 1994) and home care (Feldman, Sapienza, & Kane, 1990), our findings show that the emotional component of caregiving provides meaning to workers through the satisfaction inherent in relationships per se and through the effect of relationships on care outcomes. These DCWs believed strongly that getting to know residents and caring about them was essential to their ability to carry out the necessary care tasks and to improve the quality of residents' lives. In their exploration of informal caregiving, Caron and Bowers (2003) found that family members conceived of their role as having similar dual purposes.

We also found that some workers, particularly those who were older and had long-term careers in elder care, actively sought to promote and maintain their identities as elder caregivers. In her classic work The Ageless Self, Kaufman describes how old people “express an identity through themes which are rooted in personal experience, structural factors, and a constellation of value orientations” (1986, p. 149). Like for these old people, the structure and meaning of identity for workers was created and recreated over the course of their lives. For workers with few, if any, employment options, these claims for preferred career choices may serve as rationalizations for what cannot be. Perhaps, as Rubinstein and colleagues (1992) suggested of the old women they studied, DCWs are able to reinterpret continuity of personal identity to fit present circumstances. Elaine may explain her decision to stay in her job with, “I have always cared for elders,” because she has no other choice.

Our findings, like Karner's (1998), additionally demonstrate that the relational aspects of caregiving give workers a sense of pride in their work, which extends to themselves and allows them to “renegotiate” their low job status. Similarly, Black (2004) uses the term “moral imagination” to capture workers' reinterpretation of their roles. Using this cognitive coping strategy, labeled impression management by Goffman (1963), DCWs re-defined the situation to give the impression of higher status. These women, representative of other frontline workers in the generally low-wage, female, and increasingly non-white long-term care labor force (Katz Olson, 2003; Stone, 2001), well understand their largely invisible and devalued position in society. Their strategy to renegotiate their identity is not unlike that of members of other oppressed groups who trade their experiences of objective (economic, legal, political) oppression for subjective (moral, ethical, philosophical) superiority (Espiritu, 2003). For most of the DCWs in our study, this strategy is rooted in their lifetime experiences as black women in the American South.

Similar coping strategies helped the black workers protect themselves from the subtle and not so subtle racism they experienced from white residents. The growing presence of immigrants in the long-term care workforce suggests that such discrimination will not disappear from the long-term care arena any time soon. Recent data show that DCWs in long-term care settings more and more are women of color, both foreign and native born (Redfoot & Houser, 2005). Between 1980 and 2000, the proportion of whites decreased from 75% to 63% among native born DCWs and from 36% to14% among non-native born DCWs. This trend points to the need for increased efforts in long-term care facilities (particularly in AL where resident populations continue to be largely white) to enhance the cultural competence of all care players—residents, their family members, and facility staff. Because attitudes do not change easily, administrators also must provide support to help DCWs cope with discrimination.

Our findings also have important policy and practice implications for the allocation of DCW workloads in ALFs. Because of the importance of the staff-resident relationship for both DCWs and residents, facilities must strive to maintain staff-to-resident ratios that accommodate both emotional and physical care. Research in nursing homes suggests that the more quantifiable components of care, described by Gubrium (1975) in his classic ethnography of nursing home life as “bed and body work,” and, ultimately, profit often take precedence in the nursing home setting (Burger, Fraser, Hunt, & Frank, 1996). The increasing frailty of AL residents, coupled with the desire of most elders once in AL to age in place (Ball et al., 2004), suggests that ALFs must guard against becoming like nursing homes in that respect. We acknowledge that the relatively light workload in the two homes in this study, one not-for-profit and the other owned by a small corporation, is unusual in the growing AL industry, but we believe that manageable DCW workloads are a worthy, if not essential, goal.

Although this study makes valuable contributions to AL literature, policy, and practice, several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of participant observation and qualitative interviews facilitated an in-depth understanding of staff-resident relationships in ALFs, but this approach, along with our sample of two facilities, curtails our ability to generalize or make definitive conclusions about the larger population of ALFs and DCWs. Future research would do well to expand the facility sample to achieve variability in: state; geographic locations (e.g., urban and rural); size; retention rates; as well as the race and socioeconomic status of workers and residents. And, although the majority of DCWs are women, the voices of male DCWs are notably absent from this research. It remains to be seen how gender influences staff-resident relationships in these settings. Additional research, both qualitative and quantitative, would help to achieve a greater understanding of staff-resident relationships in ALFs.

And finally, we recognize the challenges of collecting data from research participants whose cultural worlds are much different from those of the researchers. Although one of our team had been a DCW in an assisted living DCU, we, like the residents, were white and from a higher socioeconomic class than the workers we studied. We believe that the time we spent with these workers listening to them and, when possible, helping with daily tasks helped us gain their trust and minimize these differences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R03AG022611-01) “Relationships of Care Staff in Assisted Living,” Mary M. Ball, Principal Investigator. We also would like to thank Dr. Frank J. Whittington and Dr. Candace Kemp for reading multiple manuscript drafts and providing valuable feedback.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mary M. Ball, Gerontology Institute, P.O. Box 3984, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302-3984, 404-413-5215, mball@gsu.edu.

Michael L. Lepore, Gerontology Institute, P.O. Box 3984, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302-3984, 404-964-2492, mlepore1@student.gsu.edu.

Molly M. Perkins, Rollins School of Public Health, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd., 1518-002-1AA, Atlanta, GA 30322, 404-727-8749, mmperki@emory.edu.

Carole Hollingsworth, Gerontology Institute, P.O. Box 3984, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302-3984, 404-413-5218, carolehollingsworth@gsu.edu.

Mark Sweatman, Gerontology Institute, P.O. Box 3984, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302-3984, 770-365-4726, markmb@bellsouth.net.

References

- Abel E. Representations of caregiving by Elizabeth Forster, Mary Gordon, and Doris Lessing. Research on Aging. 1995;17:42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M, Perkins M, Whittington F, Hollingsworth C, King S, Combs B. Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M, Perkins M, Whittington F, Connell B, Hollingsworth C, King S, et al. Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S202–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.s202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M, Whittington F, Perkins M, Patterson V, Hollingsworth C, King S, et al. Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Berdes C, Eckert J. Race relations and caregiving relationships: A qualitative examination of perspectives from residents and nurse's aides in three nursing homes. Research on Aging. 2001;1:109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Berdes C, Eckert J. The language of caring: Nurse's aides' use of the family metaphors conveys affective care. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:340–349. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black H, Rubinstein R. Direct care workers' response to dying and death in the nursing home: A case study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S3–S10. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black H. Moral imagination in long-term care workers. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 2004;49:299–320. doi: 10.2190/J7FV-1B8Y-MCNU-AMDW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: Exploring the views of nurse aides. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2000;14:55–64. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton W, Golden M. Profile of Pennsylvania nurse's aides. Geriatric Nursing. 1995;16:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4572(05)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger S, Fraser V, Hunt S, Frank B. Nursing homes: Getting good care there. San Luis Obispo, CA: Impact Publishers, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. Factors related to strain among home care workers: A comparison of formal and informal caregivers. 41st Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; San Francisco, CA. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Caron C, Bowers B. Deciding whether to continue, share, or relinquish caregiving: Caregiver views. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:1252–1271. doi: 10.1177/1049732303257236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide to qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Zimmerman S, Morgan L. Connectedness in residential care: A qualitative perspective. In: Zimmerman S, Sloane P, Eckert JK, editors. Assisted living: Needs, practices, and policies in residential care for the elderly. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. pp. 292–313. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu Y. Home bound: Filipino American lives across cultures, communities, and countries. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eustis N, Fischer L. Relationships between home care clients and their workers: Implications for quality of care. The Gerontologist. 1991;31:447–456. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman P, Sapienza A, Kane N. Who cares for them?: Workers in the home care industry. New York: Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Foner N. The caregiving dilemma: Work in an American nursing home. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland R. Caregivers and long-term care needs in the 21st century: Will public policy meet the challenge? : Long-term care financing project. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Galloro V. Staffing outlook grim. Modern Healthcare. 2001;31:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass T. Nobody's home: Candid reflections of a nursing home aide. Ithica: Cornell University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on management of a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber L, Allen P, Deering J. Job satisfaction of nursing assistants in long-term care. Health Care Supervisor. 1995;13:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J. Living and dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martin's; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Phillips C. High service or high privacy assisted living facilities, their residents and staff: Results from a national survey. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Rose M, Phillips C. A national study of assisted living for the frail elderly. Executive summary: Results of a national survey of facilities. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkely, CA: University of California Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis L. Pollution of incontinence and the dirty work of caregiving in a U.S. nursing home. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2001;1:84–99. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner T. Professional caring: Homecare workers as fictive kin. Journal of Aging Studies. 1998;12:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Konetzka R, Stearns S, Konrad T, Magaziner J, Zimmerman S. Personal care aide turnover in residential care settings: An assessment of ownership, economic, and environmental factors. The Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2005;24:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer S, Heacock P, Beck C. Nurse's aides in nursing homes: Perceptions of training, work loads, racism, and abuse issues. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2003;21:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R, Lamarche-Johnson H. State residential care and assisted living policy: 2004. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan R, Carthy S. Nursing home employment: The nurse's aide perspective. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1992;18:13–16. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19920201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Eckert JK, Lyon S. Small board and care homes: Residential care in transition. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moss M, Rubinstein R, Black H. The metaphor of “family” in staff communication about dying and death. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;5:S290–S296. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.s290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noelker L. The backbone of the long-term-care workforce. Generations. 2001;25:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Piercy K. When it is more than a job: Close relationships between home health aides and older clients. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:362–387. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter S, Churilla A, Smith K. An Examination of full-time employment in the direct-care workforce. The Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2006;25:356–374. [Google Scholar]

- Purk J, Lindsey S. Job satisfaction and intention to quit among frontline assisted living employees. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2006;20:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot D, Houser A. We shall travel on: Quality of care, economic development, and the international migration of long-term care workers. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska-Simmons E. Predictors of organizational commitment among staff in assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(2):195–205. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. Research on frontline workers in long-term care. Generations. 2001;25:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tellis Nayak V, Tellis Nayak M. Quality of care and the burden of two cultures: When the world of the nurse's aide enters the world of the nursing home. The Gerontologist. 1989;29:307–313. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Government Accounting Office. Nursing workforce: Recruitment and retention of nurses and nurse aides is a growing concern. Testimony statement of William J Scanlon, Director Health Care Issues. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Unpublished data. (2006). Georgia Office of Regulatory Services.