Abstract

Taurine is the most abundant free amino acid in the body and is synthesized in mammals by 2 pathways. Taurine is synthesized either from the oxidation of cysteine via cysteine dioxygenase (CDO), which generates cysteinesulfinate that is decarboxylated by cysteinesulfinic acid decarboxylase (CSAD), or from the oxidation of cysteamine by cysteamine (2-aminoethanethiol) dioxygenase (ADO). Both pathways generate hypotaurine, which is oxidized to taurine. To determine whether these pathways for taurine synthesis are present in the adipocyte, we studied 3T3-L1 cells during their adipogenic conversion and fat from rats fed diets with varied sulfur-amino acid content. CDO, CSAD, and ADO protein levels increased during adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and all of these enzymes were significantly increased when cells achieved a mature adipocyte phenotype. Furthermore, these changes were accompanied by an increased hypotaurine and taurine production, particularly when cells were treated with cysteine or cysteamine. CDO mRNA levels also responded robustly to cysteine or cysteamine treatment in adipocytes but not in undifferentiated 3T3-L1 cells. Furthermore, CDO protein and activity were greater in adipose tissue from rats fed a high protein or cystine-supplemented low protein (LP) diet than in adipose tissue from rats fed a LP diet. Overall, our results demonstrate that CDO is regulated at both the level of enzyme abundance and the level of mRNA in mature adipocytes.

Introduction

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonate) is the most abundant amino acid in the body and can be obtained preformed in the diet or synthesized from cysteine in the body (1,2). Taurine serves as a conjugation substrate for bile acids and certain other compounds, increasing their polarity and aqueous solubility. Taurine is also known to be an important organic osmolyte, and both taurine and its precursor hypotaurine can act as antioxidants (1,2). A lack of taurine during early life leads to problems with the pre- and postnatal development of the central nervous and visual systems (1,2). In addition, maternal taurine supplementation during pregnancy in mice and rats has been shown to prevent the detrimental effects of a maternal low-protein (LP) diet during pregnancy on pancreatic development and functions, such as impaired proliferation of islets and impaired insulin secretion (3–5).

In mammals, taurine can be synthesized by 2 pathways (1): the conversion of cysteine to cysteinesulfinate (CSA)3 by cysteine dioxygenase (CDO; EC1.13.11.20), followed by its decarboxylation to hypotaurine by cysteinesulfinic acid decarboxylase (CSAD; EC4.1.1.29) and the oxidation of hypotaurine to taurine and (2) the incorporation of cysteine into CoA, followed by the release of cysteamine during CoA turnover, the oxidation of cysteamine to hypotaurine by cysteamine (2-aminoethanethiol) dioxygenase (ADO; EC1.13.11.19) and the further oxidation of hypotaurine to taurine. ADO is expressed in a ubiquitous manner with high levels in most rat tissues, whereas CDO is expressed in a much more tissue- and cell type-specific manner and is particularly abundant in liver and adipose tissue (6–12). The expression of both CDO and ADO in adipose tissue suggests that adipocytes may play an important role in taurine synthesis in the body.

Over the past 2 decades, our understanding of cysteine metabolism and taurine synthesis held that the liver is the major site of CDO expression, that the liver plays the major role in responding to changes in dietary sulfur amino acid (SAA) levels by altering rates of cysteine catabolism by CDO, and that the CDO/CSAD pathway is the major route of taurine biosynthesis in vivo (9,13–16). In isolated hepatocytes and in liver of intact rats, CDO undergoes large fold changes in concentration in response to changes in cysteine availability and this regulation of CDO concentration occurs almost entirely at the level of protein turnover via regulated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. CDO is rapidly degraded in hepatocytes cultured with a low cysteine concentration or in liver of animals fed a LP diet, but accumulates and is converted to its mature form in hepatocytes cultured in medium with a higher cysteine concentration or in liver of animals fed a high-protein (HP) diet (17,18). In contrast, hepatic CDO mRNA levels are largely unresponsive to changes in dietary protein or SAA levels (19–21). Tissue ADO activity does not appear to respond to changes in dietary protein or SAA level (12).

The presence of both CDO and ADO in adipose tissues raises the possibility that adipose tissue is an important site of hypotaurine/taurine synthesis from cysteine as well as from cysteamine. However, whereas the liver has a high capacity for conversion of methionine to cysteine via the transsulfuration pathway, adipose tissue differs in that it has minimal capacity for methionine catabolism and cysteine biosynthesis by the transsulfuration pathway (22). The low capacity of adipose tissue for methionine transsulfuration is due, at least in part, to the low expression of cystathionine γ-lyase (EC 4.4.1.1) mRNA and protein in adipose tissue (22,23).

Although CDO in liver is robustly regulated in response to changes in cysteine availability, little is known about the regulation of CDO in adipose tissues. CDO mRNA expression has been shown to be upregulated during differentiation in a number of cell types, including the 3T3-L1 and C3H10T1/2 murine embryonic fibroblast/preadipocyte cell lines (7,10,24–26). Whether CDO mRNA, protein, and activity in adipose tissue respond to changes in dietary protein or SAA has not been explored.

To learn more about the expression and regulation of CDO and ADO in adipocytes, we examined the levels of taurine biosynthetic enzymes in rat adipose tissues and in differentiating 3T3-L1 cells and their responses to cysteine concentration. We examined expression of CDO and CDO enzyme activity in adipose tissue in rats fed a LP, HP, or high-cystine diet. Because CDO is known to be regulated mainly at the level of protein turnover in liver, we further explored the regulation of CDO levels in adipocytes at the level of protein abundance, as well as mRNA, in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and cell culture.

Rat studies were conducted with the approval of the Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan) were housed in a facility kept at constant temperature (∼22°C) and humidity (∼65%) with controlled lighting (14-h-light/10-h-dark cycle). All animals consumed diet and water ad libitum. Rats were initially acclimated on a standard rodent nonpurified diet (Prolab RMH 1000, PMI Nutrition International; 16.4% protein, 57.6% carbohydrate, 6.2% fat, 3.5% crude fiber). To study the effect of protein level on CDO expression, rats (125–150 g; n = 5 per treatment; 2 males, 3 females) were fed diets containing 100 g/kg casein (LP), 400 g/kg casein (HP), or 100 g/kg casein plus 8 g l-cystine (LPC) for 7 d prior to the collection of tissues. Diets were based upon the AIN-93G diet composition (27) and were prepared in pelleted form by Dyets. Rats were anesthetized with CO2; intra-abdominal (gonadal) fat and liver tissue was collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

3T3-L1 cells (ATCC) were maintained in growth medium (DMEM; Mediatech) supplemented with 10% (v:v) bovine calf serum, 4 mmol/L Glutamax (Invitrogen), 100 kU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% air atmosphere. When cells were 2 d postconfluent, they were induced to differentiate as described by Rubin (28). Briefly, cells were treated with adipogenesis induction medium [DMEM with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (FBS; JR Scientific), 4 mmol/L Glutamax, 0.5 mmol/L 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 1 μmol/L dexamethasone, 100 kU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin] for 2–3 d. Cells were then switched to adipogenesis progression medium (DMEM with 10% dialyzed FBS, 10 mg/L insulin, 1 μmol/L dexamethasone, 4 mmol/L Glutamax, 100 kU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin) for 2 d. Finally, cells were maintained thereafter in adipogenesis maintenance medium (DMEM with 10% dialyzed FBS, 4 mmol/L Glutamax, 100 kU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin).

For experiments in 3T3-L1 cells to measure the effects of cysteine analogs on CDO stability, SAA-free DMEM (Invitrogen) was used in place of standard DMEM during the experimental period and was supplemented with the designated concentrations of cysteine and/or methionine. Stock solutions of cysteine and methionine also contained bathocuproine disulfonic acid at a concentration that yielded a final concentration of 40 μmol/L bathocuproine disulfonic acid in the culture medium. Experiments were conducted between d 8 and 10 of the differentiation protocol when cells were fully differentiated. Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and then incubated for 4 h in basal adipogenesis maintenance medium prepared with SAA-free DMEM + 0.3 mmol/L l-methionine (basal, 0 mmol/L cysteine) or basal medium supplemented with 5 μmol/L lactacystin, 1 mmol/L cysteine, 1 mmol/L cysteamine, 1 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, or 1 mmol/L methionine. All culture experiments were conducted in triplicate and each experiment was repeated 3 times.

Preparation of cell and tissue lysates and western immunoblotting.

Cells were harvested into lysis buffer [50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5, 1% (v:v) Non-idet P-40, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 150 mmol/L NaCl] supplemented with 1× mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Frozen tissues were homogenized in the same buffer. Lysates and homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at ∼14,000 × g; 20 min at 4°C and the total protein content of the supernatant fraction was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce). Cell and tissue soluble proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a 0.45-μm Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blotted for immunoreactive proteins with antibodies against CDO and CSAD (8,29,30), ADO (11), fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) (Caymen Chemical), and actin (Cell Signaling Technology), using a horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody, exposed to X-ray film for chemiluminescent detection (Supersignal West Dura), and quantified using ImageJ. The CSAD antibody was a gift from Dr. Marcel Tappaz (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit and mRNA was subjected to on-column DNaseI treatment (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen); 10 ng or 25 pg cDNA was used for analysis of CDO and 18S rRNA abundance, respectively. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay probes and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The rat CDO (Rn00583853_m1CDO1) and human 18S rRNA (4319413E) probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The quantitative real-time PCR assays were conducted using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System and Applied Biosystems v1.2.3f2 software.

Enzyme assays and quantification of cysteine, cysteinesulfinic acid, taurine, and hypotaurine.

For enzyme activity assays, fat tissue was homogenized in 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid, pH 6.1, and the 18,000 × g; supernatant fraction was obtained and used to measure CSA production as a measure of CDO enzyme activity. Enzyme activity assays and HPLC to measure CSA were performed as described in detail (31). The total protein content of the supernatant fraction was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce).

Cell lysates were deproteinized by the addition of 20% (wt:v) sulfosalicylic acid to a final concentration of 5% (wt:v). The acid supernatant was obtained by centrifugation (14,000 × g; 20 min at 4°C). For the measurement of cysteine, a modified acid-ninhydrin method (32,33) was used. For the measurement of taurine and hypotaurine by HPLC, the acid supernatants and standards were diluted 1:20 with a solution of 200 mmol/L borate buffer, pH 10.4, and analyzed for hypotaurine and taurine concentrations using a precolumn o-phthalaldehyde/2-mercaptoethanol derivatization method and separation by HPLC as described in detail previously (8,18). The total protein content of the supernatant fraction was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce).

Statistical analysis.

All quantitative data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted by ANOVA and Dunnett's or Tukey's post-test procedures or by 1 sample t tests using Prism 3 (GraphPad Software). The effects of treatments were analyzed relative to the basal control treatment group at a given time point and differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

CDO expression in adipose tissue is responsive to dietary protein and cysteine.

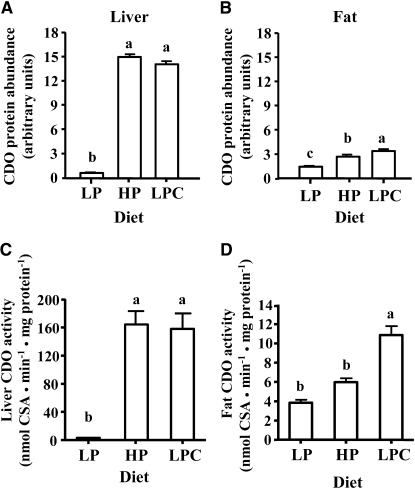

Hepatic CDO protein expression and enzyme activity are highly responsive to dietary protein or SAA, with CDO levels in rats fed a HP or high SAA diet being ∼30 times those in rats fed a LP diet (20,21). Similar to previous reports, liver CDO abundance increased to 30 times and 28 times (Fig. 1A) and liver CDO activity increased to 50 times and 48 times (Fig. 1C) the basal LP levels in rats fed the HP and LPC diets, respectively. Thus, we examined whether or not the adipose tissue, which also had a high level of CDO protein expression, was responsive to dietary protein or cysteine in vivo. Gonadal fat from rats fed a LP diet contained low levels of CDO protein, whereas gonadal fat from rats fed a HP diet or a LPC diet contained 2.0 and 2.5 times as much CDO, respectively (Fig. 1B). The addition of cystine to the LP diet resulted in a level of CDO activity that was 2.8 times that in fat of rats fed the basal LP diet (Fig. 1D). CDO activity in gonadal fat from rats fed the HP diet was 1.6 times that in rats fed the LP diet (P = 0.054). These results clearly showed that CDO in adipose, as in the liver, is highly responsive to dietary protein or cystine. Although the sample sizes were small, tissues from male and female rats had similar CDO abundance and levels of activity and so male and female data are pooled in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 .

Effect of dietary protein or cystine on CDO expression and enzyme activity in rat liver and adipose tissue. Liver or gonadal fat was collected from rats fed either a LP, HP, or LPC diet for 7 d. (A,B) Total protein lysate from liver or fat was resolved by SDS-PAGE and CDO was detected by western immunoblotting and quantified. (C,D) CDO enzyme activity was measured in liver and fat and CSA production was quantified by HPLC. Each bar represents a mean ± SEM, n = 3–5. Means without a common letter differ, P ≤ 0.05.

Expression of the taurine synthetic enzymes CDO, CSAD, and ADO is induced during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells into adipocytes.

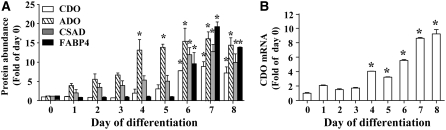

Several studies have shown that CDO mRNA is upregulated during differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes (7,24,25). The expression of CDO in these cells is thought to contribute to the production of taurine. In addition to CDO, ADO can catalyze the production of hypotaurine from cysteamine (12). As such, we examined the protein abundance of the enzymes involved in hypotaurine/taurine biosynthesis from cysteine (CDO, CSAD) and cysteamine (ADO). The abundance of CDO, CSAD, and ADO protein in 3T3-L1 cells was low early in the differentiation process but increased steadily over the period of differentiation, with increases in all these enzymes reaching significant levels compared with d 0 by d 6 (7.8 times, 11.9 times, 15.3 times the d 0 level for CDO, CSAD, and ADO, respectively) as cells achieved an adipocyte phenotype (Fig. 2A). FABP4, which is expressed only in mature adipocytes, increased to 9.5 times the d 0 level by d 6 and remained elevated from this time onwards. In addition, we analyzed the changes in CDO mRNA levels using quantitative real-time PCR relative to the d 0 time point. The expression of CDO mRNA increased steadily during the differentiation process (Fig. 2B). By d 4 of differentiation, CDO mRNA expression was 4.1-fold the d 0 level, and it had reached 9.2-fold by d 8 when cells were mature adipocytes (Fig. 2B). Clearly, all 3 taurine biosynthetic enzymes were expressed in mature adipocytes.

FIGURE 2 .

Expression of taurine synthetic enzymes during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells to adipocytes. (A) Cellular lysates were prepared from 3T3-L1 cells at the times indicated during the differentiation process. Total protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and CDO, CSAD, ADO, and FABP4 were detected by immunoblotting, quantified, and normalized to actin values. Results are shown as values relative to d 0 values set as 1. (B) CDO mRNA changes were calculated relative to d 0 of differentiation. For both A and B, each bar represents a mean ± SEM, n = 3. *Different from d 0, P ≤ 0.05.

CDO is stabilized by cysteine, cysteamine, or a proteasome inhibitor in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

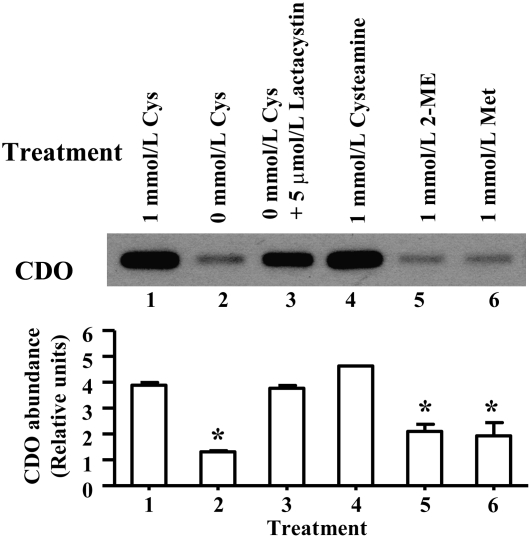

In the liver, regulation of CDO in response to cysteine occurs mainly at the level of protein degradation with little change in mRNA levels (34), but little is known about the regulation of this enzyme in adipose tissue. The stabilization of CDO protein is specific to l-cysteine in liver of rats, probably because cysteamine levels are maintained rather low in vivo, but either cysteine or cysteamine stabilized CDO in cultured primary hepatocytes (17,18). To determine whether or not CDO protein in adipocytes would also be stabilized by cysteine or cysteamine and whether this regulation was likely to be due to inhibited degradation of CDO by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated in medium containing 1 mmol/L cysteine for 24 h and then switched to treatment medium either with cysteine or no cysteine with or without lactacystin (a proteasome inhibitor), methionine, 2-mercaptoethanol, or cysteamine. One mmol/L cysteine resulted in a high level of CDO, but CDO decreased markedly in cells switched to a cyst(e)ine-free medium (Fig. 3). As in previous studies with hepatocytes, 2-mercaptoethanol was ineffective in preventing a decrease in CDO, whereas cysteamine was as effective as cysteine. The lack of an effect of methionine is consistent with the lack of activity of the transsulfuration pathway to convert methionine sulfur to cysteine in adipocytes. The proteosome inhibitor, lactacystin, also stabilized CDO, consistent with the hepatic mechanism whereby CDO degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system is blocked by high levels of cysteine (in vivo and in vitro) or cysteamine (in vitro) (17,18).

FIGURE 3 .

Regulation of CDO in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by thiols. Mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with 1 mmol/L cysteine for 24 h and then switched to treatments consisting of either cysteine (Cys), lactacystin, cysteamine, 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), or methionine (Met) at the concentrations indicated. Total protein (40 μg) was resolved by SDS-PAGE and CDO was detected by immunoblotting and quantified. Each bar represents a mean ± SEM, n = 3. *Different from cells cultured in treatment medium supplemented with 1 mmol/L cysteine, P ≤ 0.05.

3T3 cells are capable of regulating cysteine metabolism throughout their differentiation into adipocytes.

We further explored regulation of taurine synthetic enzymes by examining the capacity of CDO, as well as CSAD and ADO, to respond to an elevated concentration of cysteine or cysteamine at different time points during adipocyte differentiation. We also examined CDO mRNA changes in response to cysteine or cysteamine to determine whether or not transcriptional changes might also contribute to the observed increase in CDO expression in response to cysteine or cysteamine in adipocytes. Furthermore, we assessed the capacity of cells to synthesize hypotaurine/taurine from cysteine or cysteamine.

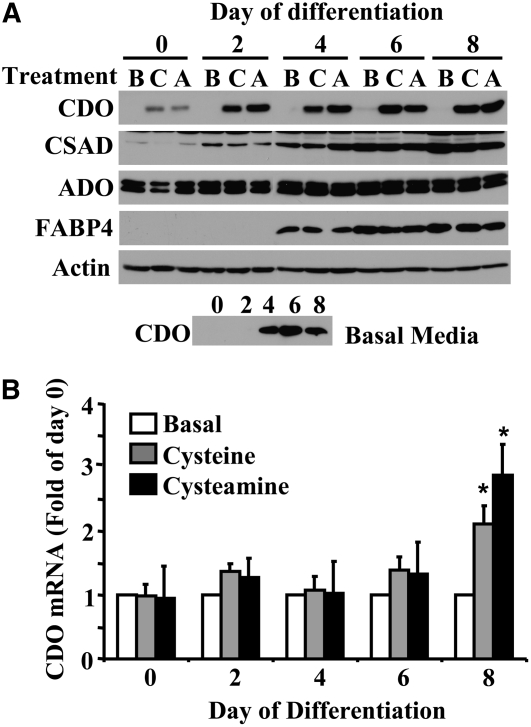

3T3-L1 cells were cultured in normal DMEM-based adipogenesis medium as for the differentiation experiment in Figure 2, except that either 1 mmol/L cysteine or 1 mmol/L cysteamine was added to the medium for the 48-h period immediately preceding harvest of the cells. The addition of cysteine or cysteamine for the 48-h period before the initiation of differentiation led to an increased CDO protein level (Fig. 4A) but no change in CDO mRNA level. Similarly, in contrast to the increases in CDO protein level, cysteine and cysteamine did not affect CDO mRNA levels for cells harvested at d 2, 4, and 6 of the differentiation protocol. In contrast, in fully differentiated adipocytes cultured with cysteine or cysteamine for the 48-h period from d 6 to d 8, a significantly greater level of CDO mRNA than that in cells cultured in basal medium (i.e. 2.1 or 2.9× the basal level for cysteine- and cysteamine-supplemented cells, respectively, on d 8) was observed. Thus, in mature adipocytes, CDO protein expression appeared to be regulated in response to cysteine availability both at the level of protein turnover and at the level of mRNA level. The western blot (longer exposure) at the bottom of Figure 4A shows that CDO protein levels increased with differentiation in adipocytes, consistent with previous results in 3T3-L1 adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 2), even though the levels for cells cultured in basal medium were always much lower than those for cells cultured in cysteine- or cysteamine-supplemented medium. Neither cysteamine nor cysteine affected either ADO or CSAD levels at any time point. This latter result was anticipated, because studies of ADO and CSAD in other tissues have indicated little or no regulation of these enzymes in response to SAA availability (12,34).

FIGURE 4 .

Expression of taurine synthetic enzymes during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells treated with cysteine or cysteamine. (A) Expression of the enzymes CDO, CSAD, and ADO were examined in 3T3-L1 cells cultured in basal medium (B) or medium supplemented with 1 mmol/L cysteine (C) or 1 mmol/L cysteamine (A) for 48 h prior to collection of cellular lysates at the times indicated over the course of the adipogenic differentiation process. Total protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and CDO, CSAD, ADO, FABP4, and actin were detected by immunoblotting. Lysates from the basal condition were rerun alone and CDO was detected by immunoblotting with longer exposure (lower blot). (B) Quantitative real-time PCR was used to measure CDO mRNA changes by treatment relative to the basal condition within each day. Each bar represents mean ± SEM, n = 3. *Different from d 0, P ≤ 0.05.

Intracellular cysteine levels are tightly regulated in vivo and in CDO-expressing cells, largely through the regulation of CDO (13). It is notable that preadipocytes, which contained very little CDO, exhibited a large increase in intracellular cysteine concentration when cultured in cysteine-supplemented medium (d 0; Fig. 5A), whereas cells with higher levels of CDO (d 2 onward; Fig. 4A) maintained intracellular cysteine levels that did not significantly differ from those in cells cultured in basal or cysteamine-supplemented medium (d 2 onward; Fig. 5A). Because cysteamine cannot be converted to cysteine, addition of cysteamine would not be expected to have much effect on intracellular cysteine concentrations.

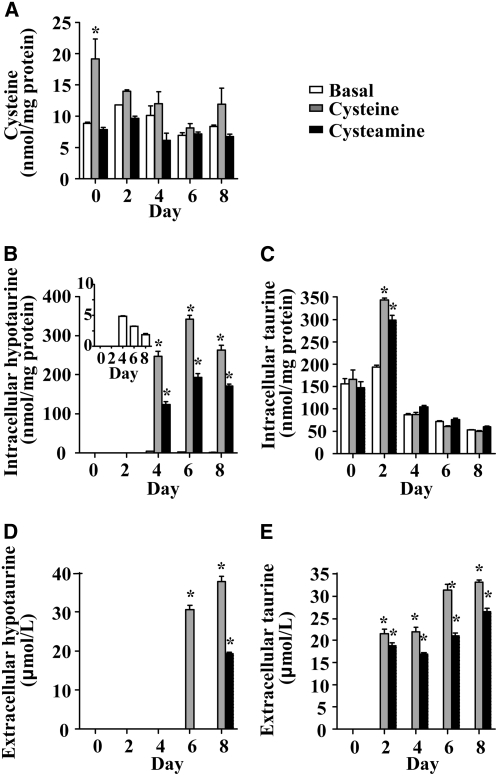

FIGURE 5 .

Effect of cysteine and cysteamine on cysteine, hypotaurine, and taurine levels in 3T3-L1 adipocyte cells cultures during adipogenic differentiation. Intracellular cysteine, hypotaurine, taurine, and extracellular hypotaurine and taurine were measured in 3T3-L1 cells cultured in basal medium or medium supplemented with 1 mmol/L cysteine (C) or 1 mmol/L cysteamine (A) for 48 h before collection of cellular lysates at the indicated times during the adipogenic differentiation process. (A) Cellular lysates from 3T3-L1 were analyzed for the measurement of cysteine. (B,C) Intracellular hypotaurine and taurine were measured in cellular lysates. The inset shows intracellular hypotaurine levels in cells cultured under basal conditions, which were too low to be visible in the main graph. (D, E) Extracellular hypotaurine and taurine were measured in media. Each bar represents a mean ± SEM, n = 3. *Different from basal on each day, P ≤ 0.05.

Hypotaurine is produced as a product of cysteine catabolism by CDO plus CSAD or as a product of cysteamine catabolism by ADO. Hypotaurine is further oxidized to taurine, but whether this occurs by an enzymatic or nonenzymatic process is not known (12). Under basal conditions, intracellular hypotaurine was detectable at d 4 of differentiation (Fig. 5B, inset), consistent with the time point at which CDO protein was detected in cells cultured in basal conditions (Figs. 2 and 4A). The addition of either cysteine or cysteamine to the medium caused a significant increase in the accumulation of intracellular hypotaurine in cells harvested at d 4, 6, and 8 (after culture for 48 h in the supplemented medium) (Fig. 5B). The increased hypotaurine production was presumably due to increased substrate for ADO (i.e. cysteamine-supplemented cells) and both increased substrate and an increased amount of enzyme for CDO (i.e. cysteine-supplemented cells) (Fig. 4A). Intracellular taurine increased with both cysteine and cysteamine treatments on d 2 but not at later time points (Fig. 5C). It may be that the amount of hypotaurine produced subsequent to d 2 of the differentiation protocol exceeded the capacity of the cells to further oxidize it to taurine or that taurine export is limited in preadipocytes.

Cells can also transport hypotaurine and taurine so the culture medium was also analyzed for hypotaurine and taurine produced and exported by the cell (Fig. 5D). Hypotaurine was detected in the medium on d 6 and 8 with cysteine treatment and d 8 with cysteamine treatment but was undetectable at all times under basal conditions. Cysteine and cysteamine treatment resulted in increased taurine concentrations in the medium at all time points except for d 0 (Fig. 5E). Taurine was undetectable in the medium under basal conditions at all time points. These results indicate that 3T3-L1 cells are capable of synthesizing a large amount of hypotaurine and taurine from cysteine and cysteamine and that the amount of hypotaurine/taurine synthesized increased progressively over the time course of differentiation, along with the progressive increases in CDO, CSAD, and ADO levels.

Discussion

The incidence of obesity has increased dramatically and has brought with it many associated health issues, such as diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Recent studies on adipose tissue have shown that this tissue has a major role in the regulation of metabolic processes, including nutrient homeostasis, and adipose tissue is no longer considered only a site for fat storage (35). Specifically, detrimental changes in glucose metabolism with obesity and aging are associated with increases in intra-abdominal visceral adiposity. Research in rodents has demonstrated that altering intra-abdominal (gonadal) fat deposits via diet, surgery, or transplantation from lean animals or other fat depot sites (i.e. subcutaneous fat) improves metabolism (36–39). In the present paper, we have shown that the gonadal adipose tissue of rats and cultured adipocytes has the capacity for cysteine metabolism. We have also demonstrated that CDO in adipocytes has the capacity to respond robustly to cysteine in vivo and in vitro and that the regulation of CDO in the mature adipocyte occurs at the level of both mRNA abundance and protein degradation.

Two pathways for taurine biosynthesis are present in adipocytes.

Taurine biosynthesis can occur through the actions of 2 separate pathways, 1 from cysteine (via CDO and CSAD) and a 2nd from cysteamine (via ADO). In the present study, we showed that mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes have an abundant capacity to synthesize taurine via both taurine synthetic pathways. The abundance of CDO, CSAD, and ADO proteins was very low or undetectable in preadipocytes but increased robustly during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. The accumulation of hypotaurine in the cell as well as taurine and hypotaurine in the medium paralleled expression of CDO in differentiating adipocytes and was increased by the addition of cysteine to the medium. Addition of cysteamine, substrate for ADO, also increased hypotaurine plus taurine production from d 2 onwards, consistent with the expression of ADO in differentiating adipocytes. This accumulation of hypotaurine is consistent with previous observations of intracellular accumulation of hypotaurine and taurine in the liver, kidney, and brain tissue of rats fed cysteamine- or cysteine-supplemented diets (12). We observed an increased export of taurine to the medium in response to cysteine or cysteamine supplementation from d 2 onwards, whereas intracellular levels remained steady, albeit less than the d 2 level, possibly indicating an increased expression of taurine transporter or a change in the efficiency of taurine export as cells achieved a mature adipocyte phenotype.

CDO in the adipose responds to cysteine availability in vivo and in vitro.

The focus of cysteine metabolism has been primarily on the liver, in which the regulation and response of CDO to cysteine in vivo and in vitro have been extensively studied (13). We found high levels of CDO protein in adipose tissue of the rat and CDO in the gonadal fat of rats responded robustly to a high level of protein or cyst(e)ine in the diet by increasing in abundance. In addition, these changes were associated with increased CDO enzyme activity, demonstrating that adipose tissue is capable of responding to changes in dietary protein intake in a manner similar to that of the liver. In vitro, both cysteine and cysteamine strongly increase the abundance of CDO protein in 3T3-L1 cells. This increase in CDO abundance in 3T3-L1 cells was observed regardless of their stage during differentiation, whether they were still preadipocytes undergoing differentiation or had finished differentiation and become mature adipocytes. The ability of cysteine to increase CDO protein abundance was also observed in cultured primary adipocytes differentiated from rat stromal vascular cells (I. Ueki and M.H. Stipanuk, unpublished results). The robust ability of the adipose tissue to respond to cysteine and the low activity of the transsulfuration pathway suggests that adipocytes may function mainly as a site for the catabolism of cysteine and raises the possibility that adipose tissue of the rat is also an important site, like the liver, for the regulated catabolism of cysteine and for taurine and sulfate production.

The regulation of CDO in adipocytes involves both mRNA and protein abundance.

Of the nonhepatic tissues that have been studied, including the kidney, lung, and brain, little or no change in either CDO protein or CDO mRNA levels in response to dietary protein or SAA intake, have been observed (34). Thus, to our knowledge, adipose tissue is the first nonhepatic tissue in which robust regulation of CDO levels in response to SAA has been observed. Our present studies indicate that the regulation of CDO protein occurs at both the level of mRNA abundance and of protein degradation in an adipocyte cell line. In the preadipocyte and during early adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells, the prominent role of post-translational regulation of CDO protein was clearly evident in samples treated with cysteine and cysteamine. We found that neither treatment resulted in any differences in CDO mRNA on d 0–6, whereas CDO protein clearly increased in response to increases in either cysteine or cysteamine during this period. In contrast, large differences (2.1 and 2.9 times for cysteine and cysteamine, respectively) in CDO mRNA abundance were observed in fully differentiated adipocytes (at d 8) that had been treated with cysteine and cysteamine for 48 h, suggesting that adipose tissue might also possess the capacity to regulate CDO expression by a transcriptional or mRNA stability mechanism. Our previous studies have consistently demonstrated that hepatic CDO mRNA levels do not change with increases in cysteine availability, whereas CDO protein abundance parallels increases in cysteine availability (19–21,34). Our data for adipocytes now raise the possibility that there is a 2nd mechanism for regulation of CDO levels in adipose tissues and this, in turn, raises the question of why CDO expression in adipose tissue would be so highly regulated.

Adipose tissue appears to be poised to function in the catabolism of cysteine, to be able to respond to changes in dietary or body cysteine levels, and to have a robust capacity to synthesize taurine. As such, adipose tissue could make a major contribution to cysteine catabolism and taurine and sulfate production in vivo. Additional studies to address specific functions served by cysteine catabolism and taurine synthesis in adipose tissue are needed and are particularly relevant, given the possible implications for obesity and inflammatory diseases.

Although the physiological function of taurine in adipocytes is not known, taurine could have antiinflammatory actions in adipose tissue. Taurine has also been shown to influence the immune response and to act as an antiinflammatory substance in the form of taurine-chloramine (40,41). Taurine-chloramine is produced by activated neutrophils in a taurine concentration-dependent manner and has been shown to reduce production of inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), by macrophages (42,43). In rats, taurine-chloramine ameliorates the effects of rheumatoid arthritis and has been shown to decrease the production of proinflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory markers such as histamine (40,41). The catabolism of cysteine and biosynthesis of taurine by adipocytes may be involved in modulating the immune response. Recent evidence links obesity to a state of chronic inflammation, and increased expression and production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, have been observed in adipose tissue from obese individuals and mice (44,45). A negative association between taurine biosynthesis and the inflammatory state is also suggested by the observations that inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα may decrease CDO expression in a human medulloblastoma cell line (7,46) and the observation that CDO mRNA is decreased in fat from obese rats (7). As a result, changes in cysteine and taurine metabolism in adipose could contribute to alterations in immune health and in obesity. Taurine, in addition to SAA, has been shown to have beneficial functions in the modulation of lipid metabolism (47). It is possible that alterations in CDO expression and taurine production are key aspects in the detrimental effects of diseases involving inflammation and the immune response, such as rheumatoid arthritis and obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Hirschberger for assistance with measurements of taurine/hypotaurine and CSA.

Supported by grant DK056649 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author disclosures: I. Ueki and M. H. Stipanuk, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: ADO, cysteamine (2-aminoethanethiol) dioxygenase; CDO, cysteine dioxygenase; CSA, cysteinesulfinic acid; CSAD, cysteinesulfinic acid decarboxylase; FABP4, fatty acid-binding protein 4; FBS, fetal bovine serum; HP, high protein; LP, low protein; LPC, low protein plus cystine; SAA, sulfur amino acid; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

References

- 1.Sturman JA. Taurine in development. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:119–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arany E, Strutt B, Romanus P, Remacle C, Reusens B, Hill DJ. Taurine supplement in early life altered islet morphology, decreased insulitis and delayed the onset of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boujendar S, Reusens B, Merezak S, Ahn MT, Arany E, Hill D, Remacle C. Taurine supplementation to a low protein diet during foetal and early postnatal life restores a normal proliferation and apoptosis of rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2002;45:856–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherif H, Reusens B, Ahn MT, Hoet JJ, Remacle C. Effects of taurine on the insulin secretion of rat fetal islets from dams fed a low-protein diet. J Endocrinol. 1998;159:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjoholm K, Palming J, Lystig TC, Jennische E, Woodruff TK, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM. The expression of inhibin beta B is high in human adipocytes, reduced by weight loss, and correlates to factors implicated in metabolic disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:1308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Shozawa C, Sano K, Kamei Y, Kasaoka S, Hosokawa Y, Ezaki O. Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) deficiency creates a vicious circle promoting obesity. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueki I, Stipanuk MH. Enzymes of the taurine biosynthetic pathway are expressed in rat mammary gland. J Nutr. 2007;137:1887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ide T, Kushiro M, Takahashi Y, Shinohara K, Cha S. mRNA expression of enzymes involved in taurine biosynthesis in rat adipose tissues. Metabolism. 2002;51:1191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SS, Chen JF, Johnson PF, Muppala V, Lee YH. C/EBPbeta, when expressed from the C/ebpalpha gene locus, can functionally replace C/EBPalpha in liver but not in adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7292–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominy JE Jr, Simmons CR, Hirschberger LL, Hwang J, Coloso RM, Stipanuk MH. Discovery and characterization of a second mammalian thiol dioxygenase, cysteamine dioxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coloso RM, Hirschberger LL, Dominy JE Jr, Lee JI, Stipanuk MH. Cysteamine dioxygenase: evidence for the physiological conversion of cysteamine to hypotaurine in rat and mouse tissues. In: Oja SS, Saransaari P, editors. Taurine 6. New York: Springer; 2006. p. 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Stipanuk MH, Dominy JE Jr, Lee JI, Coloso RM. Mammalian cysteine metabolism: new insights into regulation of cysteine metabolism. J Nutr. 2006;136:S1652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Hosokawa Y, Kodama H, Matsumoto A, Oka J, Totani M. Human cysteine dioxygenase gene: structural organization, tissue-specific expression and downregulation by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuboyama N, Hosokawa Y, Totani M, Oka J, Matsumoto A, Koide T, Kodama H. Structural organization and tissue-specific expression of the gene encoding rat cysteine dioxygenase. Gene. 1996;181:161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirschberger LL, Daval S, Stover PJ, Stipanuk MH. Murine cysteine dioxygenase gene: structural organization, tissue-specific expression and promoter identification. Gene. 2001;277:153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stipanuk MH, Hirschberger LL, Londono MP, Cresenzi CL, Yu AF. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is responsible for cysteine-responsive regulation of cysteine dioxygenase concentration in liver. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominy JE Jr, Hirschberger LL, Coloso RM, Stipanuk MH. Regulation of cysteine dioxygenase degradation is mediated by intracellular cysteine levels and the ubiquitin-26 S proteasome system in the living rat. Biochem J. 2006;394:267–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JI, Londono M, Hirschberger LL, Stipanuk MH. Regulation of cysteine dioxygenase and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase is associated with hepatic cysteine level. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bella DL, Hirschberger LL, Hosokawa Y, Stipanuk MH. Mechanisms involved in the regulation of key enzymes of cysteine metabolism in rat liver in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E326–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bella DL, Hahn C, Stipanuk MH. Effects of nonsulfur and sulfur amino acids on the regulation of hepatic enzymes of cysteine metabolism. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein JD. Methionine metabolism in mammals. J Nutr Biochem. 1990;1:228–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishii I, Akahoshi N, Yu XN, Kobayashi Y, Namekata K, Komaki G, Kimura H. Murine cystathionine gamma-lyase: complete cDNA and genomic sequences, promoter activity, tissue distribution and developmental expression. Biochem J. 2004;381:113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hackl H, Burkard TR, Sturn A, Rubio R, Schleiffer A, Tian S, Quackenbush J, Eisenhaber F, Trajanoski Z. Molecular processes during fat cell development revealed by gene expression profiling and functional annotation. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanlon PR, Cimafranca MA, Liu X, Cho YC, Jefcoate CR. Microarray analysis of early adipogenesis in C3H10T1/2 cells: cooperative inhibitory effects of growth factors and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalajzic I, Staal A, Yang WP, Wu Y, Johnson SE, Feyen JH, Krueger W, Maye P, Yu F, et al. Expression profile of osteoblast lineage at defined stages of differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin CS, Hirsch A, Fung C, Rosen OM. Development of hormone receptors and hormonal responsiveness in vitro. Insulin receptors and insulin sensitivity in the preadipocyte and adipocyte forms of 3T3–L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7570–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stipanuk MH, Londono M, Hirschberger LL, Hickey C, Thiel DJ, Wang L. Evidence for expression of a single distinct form of mammalian cysteine dioxygenase. Amino Acids. 2004;26:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reymond I, Sergeant A, Tappaz M. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA encoding rat liver cysteine sulfinate decarboxylase (CSD). Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1307:152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stipanuk MH, Dominy JE Jr, Ueki I, Hirschberger LL. Measurement of cysteine dioxygenase activity and protein abundance. Curr Prot Toxicol. 2008:6.15.1–6.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Gaitonde MK. A spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem J. 1967;104:627–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominy JE Jr, Hwang J, Stipanuk MH. Overexpression of cysteine dioxygenase reduces intracellular cysteine and glutathione pools in HepG2/C3A cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stipanuk MH, Londono M, Lee JI, Hu M, Yu AF. Enzymes and metabolites of cysteine metabolism in nonhepatic tissues of rats show little response to changes in dietary protein or sulfur amino acid levels. J Nutr. 2002;132:3369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:847–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran TT, Yamamoto Y, Gesta S, Kahn CR. Beneficial effects of subcutaneous fat transplantation on metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008;7:410–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konrad D, Rudich A, Schoenle EJ. Improved glucose tolerance in mice receiving intraperitoneal transplantation of normal fat tissue. Diabetologia. 2007;50:833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barzilai N, She L, Liu BQ, Vuguin P, Cohen P, Wang J, Rossetti L. Surgical removal of visceral fat reverses hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1999;48:94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barzilai N, Banerjee S, Hawkins M, Chen W, Rossetti L. Caloric restriction reverses hepatic insulin resistance in aging rats by decreasing visceral fat. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wojtecka-Lukasik E, Czuprynska K, Maslinska D, Gajewski M, Gujski M, Maslinski S. Taurine-chloramine is a potent antiinflammatory substance. Inflamm Res. 2006;55 Suppl 1:S17–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wojtecka-Lukasik E, Gujski M, Roguska K, Maslinska D, Maslinski S. Taurine chloramine modifies adjuvant arthritis in rats. Inflamm Res. 2005;54 Suppl 1:S21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss SJ, Klein R, Slivka A, Wei M. Chlorination of taurine by human neutrophils. Evidence for hypochlorous acid generation. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcinkiewicz J, Grabowska A, Bereta J, Stelmaszynska T. Taurine chloramine, a product of activated neutrophils, inhibits in vitro the generation of nitric oxide and other macrophage inflammatory mediators. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qusti S, Parsons RB, Abouglila KD, Waring RH, Williams AC, Ramsden DB. Development of an in vitro model for cysteine dioxygenase expression in the brain. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2000;16:243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oda H. Functions of sulfur-containing amino acids in lipid metabolism. J Nutr. 2006;136:S1666–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]