Abstract

Purpose

To characterise the biophysical, pharmacological and functional properties of the Ca2+-activated Cl- current in retinal arteriolar myocytes.

Methods

Whole-cell perforated patch-clamp recordings were made from myocytes within intact isolated arteriolar segments. Arteriolar tone was assessed using pressure myography.

Results

Depolarising voltage steps to -40 mV and greater activated an L-type Ca2+ current (ICa(L)) followed by a sustained current. On stepping back to -80 mV large tail currents were observed (Itail). The sustained current and Itail reversed close to 0 mV in symmetrical Cl- concentrations. The ion selectivity sequence for Itail was I->Cl- >glucuronate. Outward Itail was sensitive to the Cl- channel blockers 9-anthracene-carboxylic acid (9-AC; 1mM), 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS; 1mM) and disodium 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (DIDS; 1mM), but only DIDS produced a substantial (78%) block of inward tail currents at -100mV. Itail was decreased in magnitude when the normal bathing medium was substituted with Ca2+-free solution or if ICa(L) was inhibited by 1 μM nimodipine. 10 mM caffeine produced large transient currents that reversed close to the Cl- equilibrium potential and were blocked by 1 mM DIDS or 100 μM tetracaine. DIDS had no effect on basal vascular tone in pressurised arterioles, but dramatically reduced the level of the vasoconstriction observed in the presence of 10 nM endothelin-1.

Conclusions

Retinal arteriolar myocytes have ICl(Ca) which may be activated by Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. This current appears to contribute to agonist-induced retinal vasoconstriction.

Introduction

The regulatory control of retinal blood flow plays a crucial role in maintaining normal retinal function. Presently, our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in controlling retinal blood flow remains incomplete, yet an improved understanding could lead to the development of new interventions aimed at restoring adequate tissue perfusion in ocular disease states such as diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy and glaucoma. Arterioles form the main site of vascular resistance in the retinal microcirculation1 and therefore the mechanisms that control smooth muscle tone in these vessels are largely responsible for regulating regional blood flow and capillary pressure in the retina. Arteriolar smooth muscle cells are known to express a variety of functional ion channels on their plasma membranes that are involved in setting the basal level of vascular tone and in mediating contractile responses to vasoactive agents2. We have recently shown that retinal arteriolar myocytes possess large-conductance Ca2+ activated K+ (BK) channels and Kv1.5-containing voltage-activated K+ channels that exert a vasodilatory influence on resting vascular tone3-5.

Ca2+-activated Cl- channels (ClCa) have been identified in several types of vascular smooth muscle6-8, including choroidal arteriolar myocytes9. Because the Cl- equilibrium potential is usually positive to the resting membrane potential, opening of ClCa channels results in Cl- efflux and membrane depolarisation10. In vascular myocytes, ClCa channels are thought to contribute primarily to agonist-mediated responses11. Agonists can produce vasoconstriction as a consequence of intracellular Ca2+ release acting directly on the contractile apparatus or indirectly by stimulating ClCa channels, causing depolarization and the consequent opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels11. Consistent with this idea, a number of studies have demonstrated that Cl- channel blockers reduce the magnitude of agonist-induced contractions in the vasculature6,12-15.

Initial work from our own laboratory has suggested that retinal arteriolar myocytes express ClCa channels3, but their biophysical, pharmacological and functional properties have yet to be determined. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to identify and characterise the Ca2+-activated Cl- current in retinal arteriolar myocytes using the whole-cell perforated patch clamp technique and to assess their functional role in modulating basal and agonist-induced changes in retinal microvascular tone using pressure myography.

Methods

Arteriole preparation

Animal use was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-450 g) were euthanized with CO2, and enucleated. Retinal arterioles devoid of surrounding neuropile were mechanically isolated in low Ca2+ Hanks’ solution as previously described3-5. In brief, retinal segments were lightly triturated in a low Ca2+ Hanks’ solution. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 1 minute, the supernatant aspirated off and the tissue washed again with low Ca2+ medium. The suspension was then stored at 21°C until needed. Arteriolar segments remained useable for up to 10 h under these conditions.

Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

Ionic currents were recorded from retinal arteriolar myocytes still embedded within their parent arterioles using the whole-cell perforated patch-clamp technique3-5,16. Vessels were pipetted into a recording bath on the stage of a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope. Isolated arterioles (200μm-4000μm length, 20-44μm outer diameter) were anchored down with tungsten wire slips (50μm diameter) and superfused for 20 minutes with an enzyme cocktail of collagenase 1A (0.1 mg/ml) and protease type XIV (0.01 mg/ml) to remove surface basal lamina, allowing gigaseal formation. This treatment also causes the smooth muscle and endothelial layers to separate4, and the smooth muscle cells become electrically isolated from each other5. Unless otherwise stated, arterioles were continuously superfused with normal Hanks’ solution at 37°C during experimentation. Voltage-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axopatch-1D, Axon Instruments, US). Pipettes (1-2MΩ) were filled with a Cs+-based solution containing amphotericin B as the perforating agent. To ensure complete block of contaminating currents through BK and Kv channels, 100 nM Penitrem A and 10 mM 4-aminopyridine (4AP) were added to the external bathing medium3-5. After full perforation of the membrane patch had been achieved (usually 3-5 minutes), cell capacitance was determined from the time constant of a capacitance transient elicited by a 20 mV hyperpolarization from -60 mV with a sampling frequency of 20 kHz. Prior to experimentation, series resistance (15-20MΩ) and cell capacitance (7-18pF) were compensated by up to 80% using the circuitry of the amplifier. Online leak subtraction was carried out using a P/4 protocol. All data were corrected for liquid junction potentials (+2-3 mV for all bathing solutions used). Recordings were low pass filtered at 0.5 kHz and sampled at 2 kHz by a National Instruments PC1200 interface using custom software provided by J. Dempster (University of Strathclyde, UK). Drug solutions were delivered via a 7-way micro-manifold.

Pressure myography

Measurement of the diameter of intact pressurized retinal arteriole segments was performed as previously described3. Again, vessels were visualised in a recording bath using an inverted microscope. A tungsten wire slip (75×2000 μm) was laid on one end of the vessel which provided anchoring and occluded of the distal open end. Vessels were cannulated with fine glass pipettes (tip diameters 3-10μm) held in a patch electrode holder and connected to a pressure transducer and water manometer. After equilibration in Hanks’ solution for 30 minutes at 37°C, intravascular pressure was increased to 70mmHg. A section of vessel at least 150 μm away from the cannula was viewed under a x40 NA 0.6 objective focused midway through its depth. The vessels were then treated with drug-containing Hanks’ solutions and changes in the external diameter measured manually from saved video images.

Solutions

Hanks’ solution contained (in mM) 140, NaCl; 6, KCl; 5, D-glucose; 2, CaCl2; 1.3, MgCl2; 10, HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Low Ca2+ Hanks’ differed only in that it contained 0.1 mM CaCl2. For patch clamp experiments the internal solution was composed of (in mM): 138 CsCl; 1 MgCl2; 0.5 EGTA; 0.2 CaCl2; 10 HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 using CsOH). 300 μg/ml of amphotericin B was added to the internal solution. For ion substitution experiments, 86 mM NaCl from the Hanks’ solution was replaced with either equimolar NaI or NaGlucuronate. For Ca2+-free solution, Ca2+ was omitted from the external medium and 10μM EGTA was added.

4-aminopyridine (4-AP), amphotericin B, 9-anthracene carboxylic acid (9-AC), caffeine, collagenase 1A, disodium 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (DIDS), penitrem A, protease type XIV, 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS) and tetracaine were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK). Nimodipine was obtained from Alexis Biochemicals (Nottingham, UK) and endothelin-1 (Et-1) was from Tocris (Bristol, UK).

Data analysis

Currents were normalized to cell capacitance to obtain current densities (pA/pF). Data are reported as the mean ± S.E.M, and n denotes the number of vessels from which recordings were made. Unless otherwise indicated, significant differences between control and experimental treatments were determined using the paired t-test. P values <0.05 were considered significant. The following labelling convention has been used to indicate the statistical significance of differences between control and test data in all figures: no asterisk, not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

The permeability of I- and glucuronate relative to Cl- was calculated using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation17,18:

| (1) |

Where [X-]o is the concentration of the substituted ion (I- or glucuronate), [Cl-]i and [Cl-]res are the intracellular and ‘residual’ extracellular concentrations of Cl- respectively and ΔErev is the shift in reversal potential upon ion substitution. F, R and T have their usual meanings.

Results

Depolarisation-evoked Cl- current

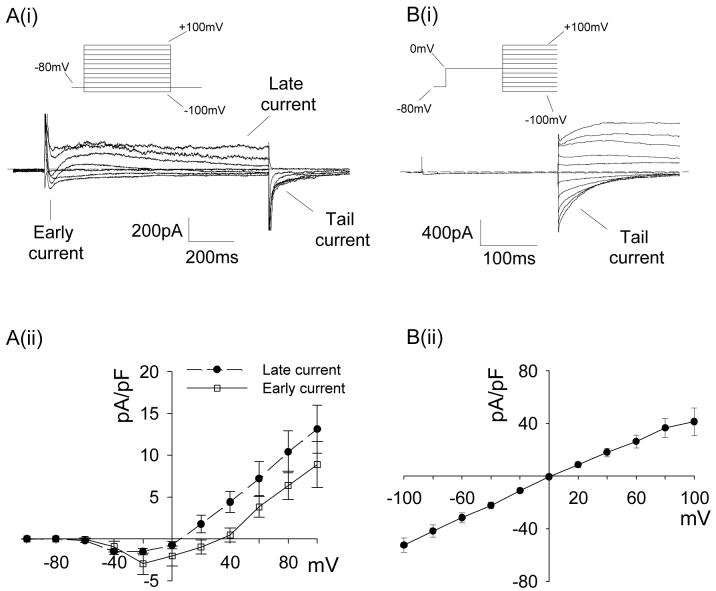

In the presence of K+ channel inhibitors, retinal arteriolar myocytes were held at a membrane potential of -80 mV and a series of 1 s voltage pulses were applied, incrementing in amplitude in 20 mV steps between -100 mV and +100 mV. This protocol evoked a family of inward, outward and tail (Itail) currents as shown in Fig 1Ai. At negative potentials an early inward current was followed by a sustained late current that was maintained throughout the voltage step. The early current, measured within the first 50 ms of the test pulse, activated at -40mV, peaked at -20mV and reversed at +40mV (Fig 1Aii). The late current, measured at the end of the 1 s test pulse, had a similar current-voltage (I-V) profile (Fig 1Aii), but reversed close to 0 mV. The difference in the reversal potentials (Erev) for the two currents suggests that they are carried by different ions. We have previously characterised the early current as an L-type Ca2+ current (ICa(L))19. The Erev for the late current is close to the calculated value for the Cl- equilibrium potential (ECl = +2.2mV), suggesting that this may be a Cl- current.

Figure 1.

Early, late and tail currents elicited by step depolarisations in retinal arteriolar myocytes. Ai. Representative current records showing early, late and tail currents evoked by a 1 s voltage step protocol (inset) applied from a hold potential of -80 mV to voltages between -100 and +100mV in 20 mV increments. Aii. Average early and late current densities plotted against test voltage (n=9). Bi. Tail currents elicited by a test steps to voltages between -100 and +100 mV in 20 mV increments (inset) applied after a 250 ms conditioning step from -80 to 0 mV. Bii. Average tail current densities (measured 10-20 ms after the start of the test step) plotted against the tail step voltage (n=8).

Itail reflects the continued activation of channels beyond the duration of the voltage pulse20. To investigate the relationship between Itail and the two preceding currents further experiments were performed. An initial conditioning step (250 ms) was fixed at 0 mV, close to the reversal potential of the late current, and subsequent steps were applied between -100 to +100 mV in 20 mV intervals. The resultant Itail was inward at negative voltages and outward at positive voltages (Fig 1Bi) and had an approximately linear I-V relationship (Fig 1Bii). Itail declined rapidly at negative voltages (τ for decay of Itail at -60 mV was 45.31 ± 4.52 ms; n=8), but was sustained during positive test steps (Fig 1Bi). Itail reversed at 0 mV, suggesting that Itail represents persistent activation of the channels underlying the late current. Because the late current and Itail appear to be mediated by the same population of channels, Itail became the primary focus during experiments to characterise these currents as Itail was larger in amplitude and could be evaluated across a wider voltage range (i.e. -100 to +100 mV as compared to -40 to +100 mV).

To test whether the late current and Itail are Cl- currents, ion substitution experiments were performed. Cl- channels in other tissues are known to be relatively impermeable to the anion glucuronate, but have a higher permeability to I- than to Cl-21. Using a 500 ms duration ramp between +100 and -100 mV, applied after a 500 ms conditioning step to 0 mV, the effect of equimolar replacement of 86 mM external Cl- with glucuronate or I- could be rapidly assessed. The use of a negative-going ramp protocol reduced the impact of the decay of Itail seen at negative potentials on the amplitude of the current. In the representative trace shown in Fig. 2Ai, Erev shifted from +2.2 to +12.2 mV when 86 mM external Cl- was replaced with equimolar glucuronate. On average Erev was shifted by 12.5 mV (Erev Cl- = +3.9 ± 2.1 mV vs. Erev glucuronate = +16.4 ± 2.5 mV, n=8, P=0.0004) and the amplitude of outward Itail was substantially reduced (Fig. 2Aii; Cl-, 32.49 ± 8.13 pA/pF vs. glucuronate, 6.18 ± 1.62 pA/pF at +80 mV, n=8, P=0.02). Using equation 1, relative permeablilites for Cl- and glucuronate were calculated as 1:0.25. As shown in Fig 2Bi, substitution with I- resulted in a negative shift in Erev. In four cells, Erev shifted by 25.1 mV in a negative direction (Erev Cl- = +0.9 ± 6.2 mV vs Erev I- = -24.2 ± 6.2 mV; P=0.002), and based upon this shift, relative permeabilities for Cl- and I- were calculated as 1:3.4. An attendant increase in the amplitude of both Itail (Fig 2Bi,ii; Cl-, 34.89 ± 13.70 pA/pF vs. I-, 73.91 ± 24.79 pA/pF at +80 mV; P=0.04) and the late current (Fig 2Bi;Cl-, -0.14 ± 0.36 pA/pF vs. I-, 13.11 ± 3.13 pA/pF at 0 mV; P=0.03) was also apparent. These findings are consistent with the suggestion that both currents result from activation of the same channel proteins. Taken as a whole, the selectivity sequence of I->Cl->glucuronate strongly suggests that the late current and Itail are carried through Cl- channels.

Figure 2.

Effect of substitution of external Cl- on Itail. Ai. Representative current traces elicited by a 500 ms voltage ramp protocol (inset) from +100 to -100 mV applied following a 500 ms conditioning step to 0mV recorded in normal Hanks’ solution and in glucuronate-substituted Hanks’. Arrows indicate reversal potentials. Bi. Original current traces recorded in normal Hanks’ solution and in I--substituted Hanks’. A&Bii. Average current densities at +80 mV in Cl- only versus (A) glucuronate- and (B) I--containing solutions (n=8 and 4, respectively).

In a further series of related experiments, the effects of three classical Cl- channel inhibitors, 9-AC, SITS and DIDS were tested on Itail22. 9-AC preferentially inhibited outward Itail (Fig 3A,C) with an 82 ± 6% block at +100 mV (control, 49.34 ± 10.93 pA/pF vs. 9-AC, 10.06 ± 5.12 pA/pF; n=5; P=0.001) as opposed to a 25 ± 10% inhibition of inward Itail at -100 mV (control, -56.66 ± 7.08 pA/pF vs. 9-AC, -39.59 ± 2.82 pA/pF; n=5; P=0.05). Similarly, 1mM SITS also displayed a voltage dependent block with 81±16% inhibition of Itail at +100 mV (control, 39.34 ± 10.74 pA/pF vs. SITS, 3.99 ± 3.75 pA/pF; n=6; P=0.04) but a non-significant reduction of 31 ± 15% at -100 mV (control, -60.69 ± 15.19 pA/pF vs. SITS, -35.03 ± 8.74 pA/pF; n=6; P>0.05). 1mM DIDS on the other hand blocked both outward and inward Itail to a similar degree (Fig. 3B,C) with the currents at +100mV and -100mV reduced on average by 92 ± 9% and 78 ± 4%, respectively (+100mV control, 39.78 ± 9.97 vs. DIDS, 3.29 ± 3.18 pA/pF; -100 mV control, -68.0 ± 12.18 pA/pF vs. DIDS, -16.65 ± 5.32 pA/pF; n=5; P=0.002 and P=0.02, respectively). A lower concentration of DIDS (10 μM) did, however, exhibit a more pronounced voltage dependence of block with 57 ± 8% inhibition at +100 mV and non-significant block (28 ± 12%) at -100 mV (+100 mV control, 46.56 ± 9.40 vs. DIDS, 23.20 ± 6.83 pA/pF; -100 mV control, -22.97 ± 4.65 pA/pF vs. DIDS, -15.44 ± 3.61 pA/pF; n=7; P=0.002 and P>0.05, respectively). Neither 9-AC, SITS nor DIDS had any discernible effect on ICa,L (p>0.05 in all cases). These pharmacological data further substantiate the view that depolarisation evokes a Cl- conductance in retinal arteriolar myocytes.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological analysis of Itail. A,B&Ci Itail elicited by alternating test steps to -100 and +100 mV applied after a conditioning step to 0 mV in normal Hanks’ solution (control) versus (A) 1 mM 9-AC, (B) 1 mM SITS and (C) 1 mM DIDS. A,B&Cii Average current densities measured in 20 mV intervals between -100 and +100 mV in the normal Hanks’ solution versus (A) 1 mM 9-AC, (B) 1 mM SITS and (C) 1 mM DIDS plotted against the test step voltage (n= 5, 6 and 5, respectively) D. Percentage inhibition of Itail by 9-AC, SITS and DIDS at different voltages calculated from the data in A,B&Cii.

Ca2+-dependence of the Cl- current

To explore the Ca2+-dependence of the depolarisation evoked Cl- current, we compared Itail before and after lowering of the extracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]o) as well as investigating the effects of the ICa(L) inhibitor, nimodipine. As shown in Fig 4Ai, both ICa(L) and Itail were decreased when the normal bathing medium was substituted with Ca2+-free solution (no added Ca2+ plus 10 μM EGTA). In 6 vessels, Itail was reduced on average by ∼75% at -100 and +100 mV (Fig 4Aii). Bath application of 1 μM nimodipine markedly reduced both ICa(L) and Itail (Fig 4B). These results suggest that the depolarisation evoked Cl- current is dependent on the influx of Ca2+ through L-type Ca2+ channels.

Figure 4.

Dependence of Itail on external Ca2+. Ai. Itail elicited by alternating test steps to -100 and +100 mV (inset) applied after a conditioning step to 0 mV in normal Hanks’ solution (control) and Ca2+-free Hanks’ (0Ca2+o). Bi. Itail elicited in normal Hanks’ solution (control) and the L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor, nimodipine (1μM). Nimodipine reduced ICa(L) by 85% and Itail by 81% and 86% at -100 and +100 mV, respectively. A&Bii. Average current densities measured at -100 and +100 mV in the normal Hanks’ solution versus (A) Ca2+-free Hanks’ and (B) 1μM nimodipine (nim; n=6 and 10, respectively).

To determine whether Ca2+ release from intracellular stores was also capable of activating the Cl- current, we tested the effects of caffeine at several different voltages between -80 to +80 mV. In retinal arteriolar myocytes, 10 mM caffeine evokes rapid global Ca2+ transients which reflect Ca2+ release from intracellular ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores23. Administration of 10 mM caffeine resulted in a transient inward current at negative voltages, little or no current at 0 mV, and a transient outward current at positive voltages (Fig 5Ai). The I-V relationship for the caffeine-induced current was approximately linear and reversed close to 0mV (Fig 5Aii), consistent with a Cl- current. In addition, the current was inhibited by ∼90% in the presence of 1 mM DIDS (Fig 5B). To exclude the possibility that caffeine activates the Cl- channels through a Ca2+-independent mechanism, we blocked caffeine-induced Ca2+ release using 100 μM tetracaine. Tetracaine totally abrogated the currents measured at -40 mV (Fig 5C), suggesting that caffeine activates the Cl- channels by raising cytosolic Ca2+.

Figure 5.

Activation of ICl(Ca) by Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. A. Original traces showing caffeine-induced currents recorded at holding potentials of -80 to +80 mV in 40 mV intervals. Aii Mean ± SEM of caffeine-induced current densities (measured as peak current versus baseline at each holding potential) (n=11). B. Caffeine-induced currents elicited at a holding potential of -40 mV before (i) and during (ii) application of 1 mM DIDS. Biii Average caffeine-induced current densities recorded at -40 mV before and during application of DIDS (n=6). C. Caffeine-induced currents elicited at a holding potential of -40 mV before (i) and during (ii) application of 100 μM tetracaine. Ciii. Average caffeine-induced current densities recorded at -40 mV before and during application of tetracaine(n=6).

Physiological Significance

The results from the experiments above suggest that retinal arteriolar myocytes possess a Ca2+-activated Cl- current (ICl(Ca)) that may be activated by Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels or Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. A further series of experiments were designed to establish the role of ICl(Ca) in regulating retinal arteriolar tone. Retinal arteriole segments were cannulated and pressurized to 70 mmHg and the effect of blocking ICl(Ca) on the external diameter of the vessels was examined. 1mM DIDS had no effect on basal vascular tone (external diameters were 36.2 ± 2.4 and 36.0 ± 2.3 μm before and after 5-min application of DIDS, respectively; n=8; P>0.05). Ca2+-activated Cl- channels have been shown to be activated by a wide range of agonists that raise intracellular Ca2+11, and we have recently shown that the vasoconstrictor peptide, endothelin-1 (Et-1), stimulates regenerative transient depolarisations in retinal arteriolar myocytes and that these depolarisations are rapidly blocked by application of a Cl- channel inhibitor24. To examine the possible involvement of ICl(Ca) in modulating Et-1-induced retinal arteriolar vasoconstriction, pressurized vessels were exposed to either Et-1 alone or Et-1 with 1 mM DIDS. Co-application of DIDS dramatically reduced the level of the vasoconstriction observed with 10 nM Et-1 (Fig 6). These findings suggest that activation ICl(Ca) represents a key signalling component regulating Et-1 induced vasoconstriction in the retina.

Figure 6.

Effect of DIDS on the Et-1-induced changes in retinal arteriolar tone. A Photomicrographs of a pressurized (70mmHg) retinal arteriole before (i) and 40 s after application 10 nM Et-1 (ii). B Photographs of a different vessel before (i) and 40 s after application 10 nM Et-1 and 1 mM DIDS. Scale bars 10 μm. C. Mean data showing the external diameter of arterioles exposed to Et-1 alone or in combination with DIDS expressed as a fraction of the initial resting diameter prior to drug exposure.

Discussion

The present study is the first to characterize ICl(Ca) in the retinal microvasculature. We studied the biophysical and pharmacological properties of ICl(Ca) in retinal arteriolar myocytes by focusing mainly on Itail. Our data are consistent with Itail being mediated by Cl(Ca) channels as: (i) it reversed close to ECl; (ii) the ion selectivity sequence was I->Cl-> glucuronate, which is similar to ICl(Ca) in other tissues25; (iii) it was reduced by the classical Cl- channel inhibitors, 9AC, SITS and DIDS; (iv) it was blocked if normal Hanks’ was substituted with Ca2+-free solution or if ICa(L) was inhibited by nimodipine; and (v) it could be activated by release of Ca2+ from caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ stores. We also examined the effects of DIDS on basal vascular tone and vasoconstriction induced by Et-1 in isolated, pressurized retinal arterioles. Inhibition of ICl(Ca) by DIDS had no effect on basal vascular tone, but did substantially reduce the vasoconstrictor response to Et-1.

The electrophysiological features of ICl(Ca) in retinal arteriolar myocytes resemble those reported for ICl(Ca) in large vessel smooth muscle in other vascular beds. In portal vein, coronary and pulmonary artery myocytes, ICl(Ca) activates slowly upon depolarization, is maintained throughout the voltage step, and exhibits long tail currents upon repolarisation8,20,26,27. In addition, in rabbit portal vein, Itail decays exponentially at potentials negative to -20 mV, but is evident as a sustained current at more positive voltages20. It has been postulated that at negative voltages the decline of Itail is determined by the slow deactivation kinetics of the Cl(Ca) channels, while at more positive voltages Itail may be sustained due to persistent influx of Ca2+ through non-inactivating voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels20. The only apparent discrepancy in the electrophysiological properties of the Cl(Ca) channels in retinal arteriolar myocytes compared to those in other vascular tissues lies in their rate of deactivation. At -60 mV, Itail decayed with a mono-exponential time constant of ∼45 ms, which is considerably faster than rate of decline of Itail seen in coronary artery and portal vein myocytes, where equivalent values are ∼160ms and ∼85ms, respectively8,20. While the exact reasons for this difference remain unclear, it is known that the deactivation kinetics of ICl(Ca) in vascular smooth muscle can be modified by external anions and the phosphorylation and redox status of the channels28-30.

The anion permeability of Cl(Ca) channels has been widely tested (for review, see11). Cl(Ca) channels are known to be less permeable to large organic anions such as glucuronate, glutamate and isothionate (permeability relative to Cl- of ∼0.1-0.39,27,31). Consistent with this, in retinal arteriolar myocytes, the calculated permeability for glucuronate was 0.25 times that of Cl-. Replacement of Cl- with I-, an anion that is known to be more permeant through Cl(Ca) channels11,21, resulted in a relative permeability value of 3.4. This is in close agreement with values reported for Cl(Ca) channels in lymphatic smooth muscle (3.232), Xenopus oocytes (3.633), portal vein myocytes (4.134) and ear artery smooth muscle (4.76). These data indicate that the permeability properties of Cl(Ca) channels in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle are similar to those previously reported in other vascular myocytes.

To assess the physiological significance of ICl(Ca) in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle cells we tested the effects DIDS on basal and Et-1-evoked changes in retinal arteriolar tone. We chose DIDS, rather than 9AC or SITS, for these experiments because we found that this drug, at a concentration of 1mM, was more effective at blocking ICl(Ca) at negative membrane potentials close to the resting membrane potential of retinal arteriolar smooth muscle cells (∼-40 to -50 mV24). Our results showed that DIDS had no effect on the diameter of pressurized retinal arterioles, indicating that Cl(Ca) channels do not appear to contribute to the control of basal vascular tone in these vessels, at least under in vitro conditions. Similarly, ICl(Ca) is not believed to participate in modulating resting vascular tone in cerebral and renal resistance vessels35,36. In contrast, several studies have suggested that stimulation of ICl(Ca), which leads to membrane depolarization and the opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, plays a pivotal role in agonist-induced contractile responses in various vascular tissues12-15. Evidence from the present work indicates similar findings in retinal arterioles since DIDS substantially attenuated the vasoconstrictor action of Et-1. A major issue that has hampered research into the functional significance of Cl(Ca) channels in the vasculature has been the poor selectivity of available antagonists. Blockers of Cl(Ca) channels, including DIDS, also inhibit other types of Cl- currents e.g. swelling- and voltage-activated Cl- currents37,38. Moreover, several inhibitors of ICl(Ca) have also been shown modify ICa(L)39,40. Our electrophysiological data showed that DIDS had no effect on ICa(L) in retinal arteriolar myocytes at the same concentration used in the mechanical studies. However, we cannot fully discount the possibility that the effects of DIDS on the Et-1-induced vasoconstriction may have been due to blockade of Cl- conductances other than ICl(Ca).

In conclusion, this study has clearly demonstrated the presence of a Ca2+-activated Cl- current in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle cells with characteristics similar to those reported in large vessel smooth muscle. ICl(Ca) does not appear to contribute to resting vascular tone in vitro, but does appear to play a prominent role in the constriction of retinal arterioles by Et-1. Future research should now be directed towards understanding the involvement of ICl(Ca) in the regulation of retinal haemodynamics in vivo under both normal and pathological conditions.

Acknowledgements

We thank The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (US), Fight for Sight (UK) and The Wellcome Trust for financial support.

Footnotes

Scientific Section: PH

Disclosure for all authors: N

Reference List

- 1.Hill DW. The regional distribution of retinal circulation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1977;59:470–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson WF. Ion channels and vascular tone. Hypertension. 2000;35:173–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGahon MK, Dash DP, Arora A, et al. Diabetes downregulates large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium beta 1 channel subunit in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2007;100:703–11. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260182.36481.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGahon MK, Dawicki JM, Scholfield CN, McGeown JG, Curtis TM. A-type potassium current in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3281–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGahon MK, Dawicki JM, Arora A, et al. Kv1.5 is a major component underlying the A-type potassium current in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1001–H1008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01003.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amedee T, Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics of chloride currents activated by noradrenaline in rabbit ear artery cells. J Physiol. 1990;428:501–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne NG, Large WA. Membrane ionic mechanisms activated by noradrenaline in cells isolated from the rabbit portal vein. J Physiol. 1988;404:557–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamb FS, Volk KA, Shibata EF. Calcium-activated chloride current in rabbit coronary artery myocytes. Circ Res. 1994;75:742–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis TM, Scholfield CN. Transient Ca2+-activated Cl-currents with endothelin in isolated arteriolar smooth muscle cells of the choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leblanc N, Ledoux J, Saleh S, et al. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:541–56. doi: 10.1139/y05-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca(2+)-activated Cl- conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C435–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmines PK. Segment-specific effect of chloride channel blockade on rat renal arteriolar contractile responses to angiotensin II. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:90–4. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(94)00170-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Criddle DN, de Moura RS, Greenwood IA, Large WA. Effect of niflumic acid on noradrenaline-induced contractions of the rat aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1065–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pacaud P, Loirand G, Baron A, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Ca2+ channel activation and membrane depolarization mediated by Cl- channels in response to noradrenaline in vascular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;104:1000–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takenaka T, Epstein M, Forster H, Landry DW, Iijima K, Goligorsky MS. Attenuation of endothelin effects by a chloride channel inhibitor, indanyloxyacetic acid. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F799–F806. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:145–59. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman DE. Potential, impedance and rectification in membranes. J Gen Physiol. 1943;27:37–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.27.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgkin AL, Katz B. The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of the giant axon of the squid. J Physiol. 1949;108:37–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGahon MK, Zhang X, Scholfield CN, Curtis TM, McGeown JG. Selective downregulation of the BKb1 subunit in diabetic arteriolar myocytes. Channels. 2007;1:e1–e3. doi: 10.4161/chan.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwood IA, Large WA. Analysis of the time course of calcium-activated chloride “tail” currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1996;432:970–9. doi: 10.1007/s004240050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron A, Pacaud P, Loirand G, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Pharmacological block of Ca(2+)-activated Cl- current in rat vascular smooth muscle cells in short-term primary culture. Pflugers Arch. 1991;419:553–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00370294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scholfield CN, Curtis TM. Heterogeneity in cytosolic calcium regulation among different microvascular smooth muscle cells of the rat retina. Microvasc Res. 2000;59:233–42. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholfield CN, McGeown JG, Curtis TM. Cellular physiology of retinal and choroidal arteriolar smooth muscle cells. Microcirculation. 2007;14:11–24. doi: 10.1080/10739680601072115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hume RI, Thomas SA. A calcium- and voltage-dependent chloride current in developing chick skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1989;417:241–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan XJ. Role of calcium-activated chloride current in regulating pulmonary vasomotor tone. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L959–L968. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saleh SN, Greenwood IA. Activation of chloride currents in murine portal vein smooth muscle cells by membrane depolarization involves intracellular calcium release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C122–C131. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00384.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwood IA, Large WA. Modulation of the decay of Ca2+-activated Cl-currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells by external anions. J Physiol. 1999;516(Pt 2):365–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0365v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol. 2001;534:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenwood IA, Leblanc N, Gordienko DV, Large WA. Modulation of ICl(Ca) in vascular smooth muscle cells by oxidizing and cysteine-reactive reagents. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s004240100709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwood IA, Large WA. Properties and roles of chloride channels in smooth muscle. In: Kozlowski R, editor. Chloride channels. ISIS Medical Media Ltd; Oxford: 2000. pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toland HM, McCloskey KD, Thornbury KD, McHale NG, Hollywood MA. Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) current in sheep lymphatic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1327–C1335. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuruma A, Hartzell HC. Bimodal control of a Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel by different Ca(2+) signals. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:59–80. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, Large WA. Noradrenaline-evoked cation conductance recorded with the nystatin whole-cell method in rabbit portal vein cells. J Physiol. 1991;435:21–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson MT, Conway MA, Knot HJ, Brayden JE. Chloride channel blockers inhibit myogenic tone in rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 2):259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.259bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takenaka T, Kanno Y, Kitamura Y, Hayashi K, Suzuki H, Saruta T. Role of chloride channels in afferent arteriolar constriction. Kidney Int. 1996;50:864–72. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dick GM, Bradley KK, Horowitz B, Hume JR, Sanders KM. Functional and molecular identification of a novel chloride conductance in canine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C940–C950. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartzell HC, Qu Z. Chloride currents in acutely isolated Xenopus retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Physiol. 2003;549:453–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dick GM, Kong ID, Sanders KM. Effects of anion channel antagonists in canine colonic myocytes: comparative pharmacology of Cl-, Ca2+ and K+ currents. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1819–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doughty JM, Miller AL, Langton PD. Non-specificity of chloride channel blockers in rat cerebral arteries: block of the L-type calcium channel. J Physiol. 1998;507(Pt 2):433–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.433bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]