Abstract

Sylamer is a method for detecting microRNA target and small interfering (si)RNA off-target signals from expression data. The input is a ranked genelist from up to downregulated 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) following an miRNA or RNAi experiment. The output is a landscape plot that tracks occurrence biases using hypergeometric P-values for all words across the gene ranking. The utility, speed, and accuracy of the approach on several miRNA and siRNA datasets are demonstrated.

Analysis of overrepresented features in lists of genes is a powerful tool for associating function with biological effects. Instead of using a single cutoff and thus a single genelist, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis1 (GSEA) uses all the genes, ranked according to how they change in the experiment. This approach removes the need for cutoffs, instead searching for coordinated shifts in complete pathways or gene sets of biological interest, even if many individual genes might not lie at the top of the ranked genelist1.

We developed an algorithm, Sylamer, to provide functionality similar to GSEA for nucleotide patterns in sequences instead of annotations. Sylamer rapidly assesses over- and under-representation of nucleotide words of specific length in ranked genelists. Using multiple cutoffs it asks whether each word is more abundant at one side of the list than expected when compared to the rest. Significance is calculated using hypergeometric statistics. Sylamer is freely available, simple to use and extremely fast (Supplementary Fig. 1 online), making it ideal for genome-scale studies.

We applied Sylamer to words complementary to seed regions of microRNAs (miRNAs) or small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of genes. The seed region is a consecutive stretch of bases of length 6-8nt, at the 5′ end of the miRNA2. It has been shown that miRNA regulation of target transcripts is detectable from mRNA expression changes3-5. Hence, if enrichment of seed words in 3′UTRs correlates with the ranking of genes according to their change during a miRNA experiment, part of the expression changes can be attributed to direct effects. This approach has been validated and it was shown that particular miRNAs can have major effects on tissue or developmental expression profiles, where that miRNA is known to be differentially expressed3,6. Similarly, RNA interference (RNAi) experiments can be assessed to determine whether the resulting gene expression changes are likely due to the intended knock-down or secondary, miRNA-like, off-target effects7, 8. Hence, our goal is to test for the involvement of a particular miRNA or siRNA in an experiment, through assessment of enrichment and depletion of seeds across a ranked set of 3′UTRs.

Existing motif discovery methods9-13 are not explicitly designed for this purpose (see Supplementary Discussion online). In many cases, these methods require significant post-processing and can be extremely slow when run genome-wide. Most algorithms are designed to find enriched motifs, usually one at a time, and can miss sub-optimal motifs. Moreover, most methods are not exhaustive, and incapable of discovering depletion signals. In the context of miRNA and siRNA analysis, correction for UTR length and compositional biases is essential. Sylamer takes these issues into account when assessing the effects of small-RNA binding on expression data. Two previous studies3, 6 were aimed at this problem, but their methods are not available and fall short in ways of scalability, the ability to address composition biases, or the possibility of discovering an enrichment-based cut-off (Supplementary Discussion).

In miRNA knockout experiments, transcripts that are actively downregulated by a miRNA will be upregulated in the knockout and shifted towards the top of the gene list as determined by differential expression. It is to be expected that leading subsets of the genelist are enriched in transcripts that are in vivo targets of this miRNA. Sylamer can be used for fast verification and quantification of this hypothesis, by gauging the significance of the enrichment P-value of seed matches relative to background P-values of all other words. An intuitive way to visualize the results is to generate a landscape plot showing for each word its associated log-transformed P-values. Over- and underrepresentation are plotted on the positive and negative y-axis, respectively. A typical observation in the case of miRNA knockout data is a steep incline in overrepresentation in the leading subsets, involving hundreds of genes (Fig. 1). If a significant curve is stretched across a large part of the gene list with no clear peak at either end, the landscape plot can be used as qualitative support for the hypothesis that the relevant miRNA is involved (Supplementary Discussion).

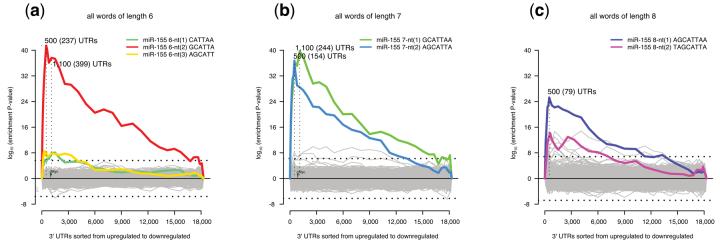

Figure 1. Mouse miR-155 knockout experiment.

Sylamer enrichment landscape plots for a) 6nt, (b) 7nt and (c) 8nt words. In each case, the x-axis represents the sorted genelist from most upregulated (left) to most downregulated (right). The y-axis shows the hypergeometric significance for each word at each leading bin. Positive values indicate enrichment (−log10 (P-value)) and negative values, depletion (log10(P-value)). The horizontal line represents an E-value threshold (Bonferroni corrected) of 0.01. Vertical lines indicate significance peaks across bins for a given word with the number of sequences indicated and (in parentheses) the number possessing the appropriate match. Grey lines show the profiles of words unrelated to the seed region of miR-155, while colored lines represent words complementary to the seed-region. Some grey lines appear to pass the E-value threshold, these 7nt and 8nt words contain the core 6nt seed flanked by mismatches. The position of a previously validated target (c-Myc) within the genelist is indicated by a green triangle.

The primary goal of Sylamer is to establish whether miRNAs or siRNAs are directly affecting gene expression and the extent of any effect. It may also be desirable to produce a list of candidate genes that may be direct targets, for further computational or experimental validation (e.g. reporter assays). In such cases, Sylamer is used to first establish whether any miRNA or siRNA has a significant effect and to choose an appropriate threshold. If a clear enrichment peak is found near the beginning of the ranked genelist, results for hexamers, heptamers and octamers should be compared and the shape of the curves and peak locations should approximately agree. The peak closest to the start of the ranking can be chosen as a conservative threshold (Supplementary Discussion). Above this threshold, a list of genes whose sequences contain appropriate word matches to a specific miRNA or siRNA is produced as a set of candidate targets supported by expression data.

In order to determine the effectiveness of our approach for the detection of enriched/depleted miRNA binding signals we applied it to two published datasets (Supplementary Data 1 and 2 online). The first dataset derives from a mouse knockout model of miR-155 (bic)5. Here, expression data were obtained for T-helper (Th1) cells from both knockout and wild-type animals (Supplementary Methods online). Each gene on the array (for which a 3′UTR was available) was ranked from most upregulated to most downregulated according to fold-change t-statistic. Our goal is to reliably determine whether the greatest contribution to gene expression changes are direct effects resulting from loss of miR-155 mediated repression. The sorted genelist and associated 3′UTR sequences were supplied to Sylamer. The resulting enrichment analysis plot (Fig. 1) clearly shows that most words drift randomly without showing any significance. A strong signal is however evident for 6 (P < 1×10−41), 7 (P < 1×10−36) and 8nt (P < 1×10−25) words corresponding to the seed-region of miR-155, peaking at ≈500 genes. This indicates that these most upregulated genes are enriched in potential miR-155 binding sites and that their observed over-expression is likely due to the absence of miR-155 in the knockout sample. In a related experiment using Th2 cells, strong compositional biases masked the biological effect of the miRNA. In this case, the compositional bias correction of Sylamer recovers a biologically meaningful result (Supplementary Fig. 2). Another issue that hampers such analyses is the effect of biological variability and random noise in the context of expression data. Sylamer proves robust with respect to both of these factors (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

In the second experiment we re-analyze gene expression data from maternal zygotic Dicer mutant (MZ-Dicer) Zebrafish embryos4,14. These fish cannot produce significant quantities of functional miRNAs14. Here the role of an early developmental miRNA (miR-430) is assessed by comparing mutant fish against those fish injected with synthetic miR-430. In this case, if miR-430 is significantly affecting gene expression we expect the effect to be most evident in downregulated genes (i.e. gain of miR-430 mediated repression). The results again show (Supplementary Fig. 5) that most words show no significant enrichment/depletion across the genelist with the exception of the words directly corresponding to the seed region of miR-430. As expected, this signal is observed in the downregulated section of the genelist (P < 1×10−26 at 6nt). This reconfirms the hypothesis that injection of miR-430 leads to direct repression of its target transcripts.

An interesting observation from these analyses are differences in the shape of the curves. The miR-155 result (Fig. 1) shows a sharp peak, with maximum value very close to the start of the genelist, whilst in the miR-430 result (Supplementary Fig. 5) the curve is broader, peaking near the middle. Sharp peaks may imply that the miRNA has a smaller set of targets, and that most expression changes are due to direct effects of the miRNA. Broad peaks probably represent cases when measurable targets are a much larger fraction of the genome or where these targets have many important secondary effects (a targeted transcription factor will itself cause expression changes). Since secondary targets are unlikely to be targets of the miRNA, their position in the ranking dilutes enrichment signals, extending it away from the extremes. These speculations should be taken with caution, since the injection of miR-430 leads to a non-physiological condition. Nevertheless, as more knockout experiments become available it will be interesting to test these hypotheses.

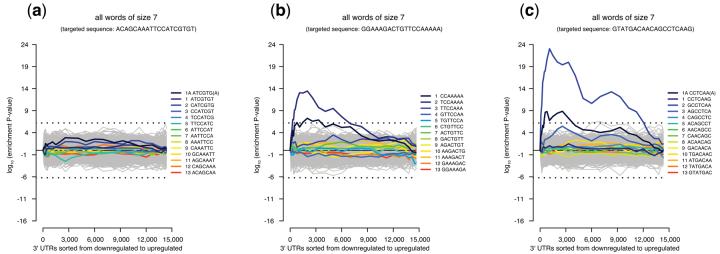

Recently it was shown that many off-target effects observed in RNAi experiments are due to siRNAs acting as miRNAs on unintended targets7. This creates serious issues for genome-wide screens as designed siRNAs may be unintentionally affecting the expression of hundreds of genes. We applied Sylamer to data derived from gene expression studies following RNAi to determine whether this effect can be directly detected. Our hypothesis is that a successful RNAi experiment should not show significant enrichment or depletion of 6-8nt words and any gene-expression changes observed are secondary effects following successful knockdown of the intended target. Conversely, if an siRNA is binding other transcripts (off-targets), we expect to observe specific enrichment of complementary words to the 5′ end of that siRNA in downregulated genes. The size and extent of any observed enrichment may also be used to evaluate how serious this effect is.

A previous off-target study used microarrays to measure the effects of transfecting 12 different siRNAs into HeLa cells7. From this, we produced, for each transfection experiment, a genelist ranked according to fold-change (Supplementary Data 3) starting with the most downregulated genes (likely to be direct off-targets). In most cases there is significant enrichment of words matching the 5′ end of the siRNA (Fig. 2). It can be seen that the effect on the expression profile is due to a miRNA-like effect, since the only significant words are those that match to the beginning of the siRNA. In agreement with previous results15, we observed a positive correlation between the maximum enrichment value caused by each siRNA and the total number of its seed matches in human 3'UTRs (Supplementary Fig. 6). As a negative control we take the maximum enrichment values for each seed match in all the experiments except the one in which the corresponding siRNA was transfected. Here, the correlation disappears and enrichment values fall within the expected range.

Figure 2. Human RNAi off-target analysis.

Sylamer enrichment plots for: (a) Enrichment profile for a successful RNAi probe which does not appear to exhibit any off-target effects according to sorted expression data, (b) RNAi probe showing off-target effects as evidenced by strong enrichment of words matching its seed region for the 2,500 most downregulated transcripts, (c) an RNAi probe exhibiting a very strong off-target effect involving more than 3,000 transcripts. Dotted lines represent an E-value threshold (Bonferroni corrected) of 0.01. Each possible word matching the siRNA is shown in colour.

Sylamer is a tool for computing word over- and underrepresentation P-values in nested bins across a ranked sequence universe. This method can be applied to any ordered list of RNA or DNA sequences, but has been specifically designed with miRNA and siRNA binding analysis in mind. A detailed description of the method is available (Supplementary Methods). Sylamer is freely available at: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright/sylamer/ under the GNU General Public License (GPL) and on the Nature Methods website. Both the command-line application and a simple JAVA graphical interface are provided.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Grocock, W. Khong, H. Saini, S. Manakov, J. van Helden, A. Giraldez and W. Huber for useful discussions. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farh KK, et al. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giraldez AJ, et al. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006;312:75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez A, et al. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sood P, Krek A, Zavolan M, Macino G, Rajewsky N. Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2746–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birmingham A, et al. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat Methods. 2006;3:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson AL, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nature biotechnology. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tompa M, et al. Assessing computational tools for the discovery of transcription factor binding sites. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nbt1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foat BC, Morozov AV, Bussemaker HJ. Statistical mechanical modeling of genome-wide transcription factor occupancy data by MatrixREDUCE. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e141–149. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eden E, Lipson D, Yogev S, Yakhini Z. Discovering motifs in ranked lists of DNA sequences. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanay A. Extensive low-affinity transcriptional interactions in the yeast genome. Genome research. 2006;16:962–972. doi: 10.1101/gr.5113606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger MF, et al. Compact, universal DNA microarrays to comprehensively determine transcription-factor binding site specificities. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24:1429–1435. doi: 10.1038/nbt1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giraldez AJ, et al. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson EM, et al. Experimental validation of the importance of seed complement frequency to siRNA specificity. RNA (New York, N.Y. 2008;14:853–861. doi: 10.1261/rna.704708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.