Abstract

Objectives To study the duration of depression, recovery over time, and predictors of prognosis in an older cohort (≥55 years) in primary care.

Design Longitudinal cohort study, with three years’ follow-up.

Setting 32 general practices in West Friesland, the Netherlands.

Participants 234 patients aged 55 years or more with a prevalent major depressive disorder.

Main outcome measures Depression at baseline and every six months using structured diagnostic interviews (primary care evaluation of mental disorders according to diagnoses in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition) and a measure of severity of symptoms (Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale). The main outcome measures were time to recovery and the likelihood of recovery at different time points. Multivariable analyses were used to identify variables predicting prognosis.

Results The median duration of a major depressive episode was 18.0 months (95% confidence interval 12.8 to 23.1). 35% of depressed patients recovered within one year, 60% within two years, and 68% within three years. A poor outcome was associated with severity of depression at baseline, a family history of depression, and poorer physical functioning. During follow-up functional status remained limited in patients with chronic depression but not in those who had recovered.

Conclusion Depression among patients aged 55 years or more in primary care has a poor prognosis. Using readily available prognostic factors (for example, severity of the index episode, a family history of depression, and functional decline) could help direct treatment to those at highest risk of a poor prognosis.

Introduction

At all ages depression is a common and disabling condition. Although physical disorders and dementia increase noticeably with age, both the prevalence and the consequences of depressive disorders retain an enormous impact on the health of ageing populations. The effects of depression are well documented on daily functioning; wellbeing1; the onset and prognosis of chronic physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disorders2 and diabetes3; mortality4; and utilisation of health services.5 Although the importance of depression in later life is widely acknowledged and recent trials have shown convincingly that treatment can be effective6 7 depression in most older patients remains undiagnosed and therefore untreated.8 9 10 Given the increase in the ageing population, it is unlikely that even health services with good resources will be able to provide treatment for all older patients with depression. It is therefore important to be able to predict the outcome and to identify those patients most at risk of a poor outcome such as chronicity. As most older depressed patients contact their general practitioner, the most relevant data on prognosis are in the setting of primary care.11

Although several studies on prognosis are available, few have been done in primary care, included sufficient numbers for analyses, had access to adequate diagnostic data at baseline and follow-up, or tested the impact of prognostic factors, while using enough observations to be able to model the variability in the prognosis of a major depressive disorder.12 We studied a group of older patients with depression in primary care over three years to provide accurate estimates of the duration of depressive episodes, the likelihood of recovery over time, and predictors of the prognosis.

Methods

The West Friesland Study is a cohort study on depression in later life (≥55 years) in primary care, with follow-up for three years. We recruited general practitioners in West Friesland, a rural area in the north west of the Netherlands. Thirty four general practitioners from 32 practices provided patients for the study.

From June 2000 to December 2002 we used a two stage screening procedure to recruit potential participants with a prevalent major depressive disorder. This method is described in detail elsewhere.13 Briefly, consecutive patients aged 55 or more visiting their general practitioner were invited to fill in the geriatric depression scale-15 items,14 15 regardless of the reason for consultation. Patients with a score above the cut-off of 5 were invited for a diagnostic interview using the primary care evaluation of mental disorders,16 which was carried out by trained interviewers within 14 days of the depression scale having been completed. By using this method we were able to include the whole spectrum of patients with depression seen in general practice, from new cases to patients with depression who were receiving long term treatment. We interviewed participants every six months for three years. Written informed consent was obtained.

Depression

A major depressive disorder according to criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, was diagnosed using the primary care evaluation of mental disorders (range 0-9).16 This instrument comprises nine items for depression and was designed for diagnosing major depressive disorders in primary care settings for clinical and research use. It is easy to use in daily practice and is recommended by the Dutch College of General Practitioners.17

We assessed the course of depression every six months using the primary care evaluation of mental disorders and the Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale (range 0-60),18 a higher score indicating more severe depression. This scale was designed to measure the severity of depression. A cut-off of 10 defines recovery from depressive symptoms.19 In the present study we defined recovery as the patient no longer fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorders and having a score of less than 10 on the Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale.

Potential predictors of prognosis

We used structured questionnaires at baseline and at one, two, and three years to collect information on personal characteristics, including age, sex, living situation, years of education, comorbid physical illness, and use of medication. The questionnaire for chronic somatic comorbidity contains a list of somatic diseases: pulmonary disease (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis), cardiovascular diseases, peripheral arterial diseases, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, other arthritis, or malignancies.20 We chose the cut-off of none versus one versus more than one disease to produce subgroups of patients with more or less comorbidity. We used the mini-mental status examination to measure cognitive decline annually.21 A cut-off of 24 defines cognitive impairment.22 Comorbid anxiety was assessed using the anxiety questionnaire of the primary care evaluation of mental disorders, which inquires about panic attacks in the past month.16 We used the diagnostic interview schedule23 to assess the age at onset of the first depressive episode, family history of depression, and the number of previous episodes of depression. Early onset depression was defined as a first depressive episode before age 55. We categorised the number of previous episodes as none versus one versus more than one to produce subgroups of patients with a history of depression. Finally, we ascertained physical functioning annually using the physical component scale of the medical outcome study 36-items, short form (range 0-100),24 25 a higher score indicating better physical functioning.

Statistical analysis

Dropouts

When appropriate we used independent t tests or χ2 tests to compare the baseline characteristics of participants with only a baseline measurement with those who had measurements at follow-up. To explore the characteristics of dropouts we compared participants who had fewer than four measurements with those who had four or more.

Duration of depressive episodes and likelihood of recovery over time

We analysed the duration of the episodes of major depressive disorders using time to recovery as the outcome measure. Time to recovery and the likelihood of recovery at different time points were estimated using Kaplan Meier methods. For these analyses we included patients with at least one follow-up measurement.

Potential predictors of outcome

We used Cox regression analyses to identify determinants at baseline predicting poor outcome (no recovery during follow-up). Firstly, we investigated whether there was a linear relation between the potential predictor variables and the outcome. We divided those variables with non-linear relations into categories (two or three), using cut-off scores described in the literature or using the median of the sum score. Secondly, we carried out univariable regression analyses for all potential predictors with the outcome measure. For the multivariable analyses we selected variables that might be associated with the outcome (P<0.20). Thirdly, we entered the predictors simultaneously in a multivariable regression model. We constructed the best predictive model using a manual backward selection method. We deleted the variables with the lowest predictive value (the largest P value in the multivariable model). The best fitting model was tested with the log likelihood ratio test (P<0.10). All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 15.0.

Besides the predictors at baseline we also explored changes in these variables during follow-up using data from the annual measurements. We compared the results of those who had recovered with those who still had depression. We used the same cohort as that for Cox survival analyses—that is, patients with a major depressive disorder at baseline and at least one follow-up measurement.

Results

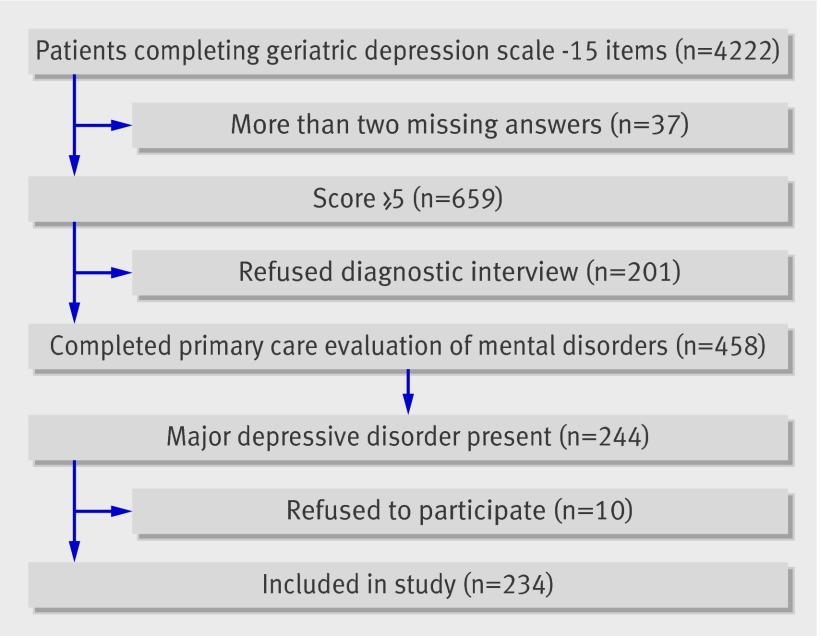

Figure 1 shows the flow of respondents through the study. Overall, 4222 of 5395 (78.3%) patients who were invited to fill in the geriatric depression scale completed the questionnaire. Non-responders were more often men and of similar age. Thirty seven responders (0.9%) were excluded because they had missed more than two answers on the depression scale. Of those who completed the questionnaire, 659 (16%) scored above the cut-off of 5. Of these, 458 (70%) gave informed consent for a diagnostic interview using the primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Responders and non-responders were not significantly different for age (mean difference 1.0 year, 95% confidence interval −0.5 to 2.6; P=0.175), sex (odds ratio 1.0, 95% confidence interval 0.7 to 1.4; P=0.822), or depression score (mean difference 0.13, −0.6 to 0.3; P=0.658).

Fig 1 Flow of respondents through study

Of the 458 patients who took part in the diagnostic interview, 244 (53%) fulfilled the criteria for a major depressive disorder of whom 234 (96%) agreed to participate in the baseline interview. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the cohort. Participants who missed an assessment were invited to successive ones.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cohort of older depressed patients (n=234) in primary care, the Netherlands. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Patients with major depressive disorder (n=234) |

|---|---|

| Age (years): | |

| 55-64 | 115 (49) |

| 65-74 | 73 (31) |

| ≥75 | 46 (20) |

| Women | 146 (62) |

| Educational level (years): | |

| Low (0-6) | 73 (31) |

| Middle (7-10) | 146 (62) |

| High (>10) | 15 (6) |

| Living alone | 87 (37) |

| Depression: | |

| Mean (SD) MÅDRS score (0-60) | 19.6 (7.8) |

| Mean (SD) PRIME-MD score (0-9) | 6.6 (1.3) |

| Depression in family | 67 (29) |

| Previous depressive episodes: | |

| 0 | 22 (10.2) |

| 1 | 41 (19.0) |

| ≥1 | 153 (70.8)* |

| Early onset depression (<55 years) | 148 (63) |

| Other: | |

| Mean (SD) MMSE score | 26.7 (2.8) |

| Anxiety | 76 (33) |

| Chronic illness: | |

| 0 | 30 (13) |

| 1 | 66 (28) |

| ≥1 | 138 (59) |

| Mean (SD) functional limitations (0-100) | 40.8 (13.2) |

| Treatment for depression: | |

| None | 141 (60) |

| Antidepressants | 72 (31) |

| Referral | 21 (9) |

MÅDRS=Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale; PRIME-MD=primary care evaluation of mental disorders; MMSE=mini-mental state examination.

*Answers missing for 17 cases.

Dropouts

Two hundred and four participants (87%) had at least one follow-up measurement and were analysed. Thirty had only completed the baseline interview. They were older than those with follow-up measurements (mean difference 4.1 years, 0.8 to 7.4; P=0.04), but were not significantly different for sex (odds ratio 1.1, 0.5 to 2.5; P=0.77), level of education (low v middle v high; P=0.87), categories of comorbidity (none v one v more than one; P=0.37), living alone or with others (odds ratio 0.7, 0.3 to 1.7; P=0.52), or baseline depression score (mean difference 0.4, −0.1 to 0.9; P=0.10).

Overall, 175 respondents (75%) completed four or more of the seven assessments during follow-up. Those with fewer than four measurements were older (mean difference 4.6 years, 2.1 to 7.1; P<0.01) and had a lower level of education (P=0.04) but were not different for sex (odds ratio 0.6, 0.3 to 1.1; P=0.07), categories of comorbidity (P=0.25), living alone or with others (odds ratio 1.2, 0.6 to 2.2; P=0.60), or baseline depression score (mean difference 0.2, −0.2 to 0.5; P=0.44).

Duration of depressive episodes and likelihood of recovery over time

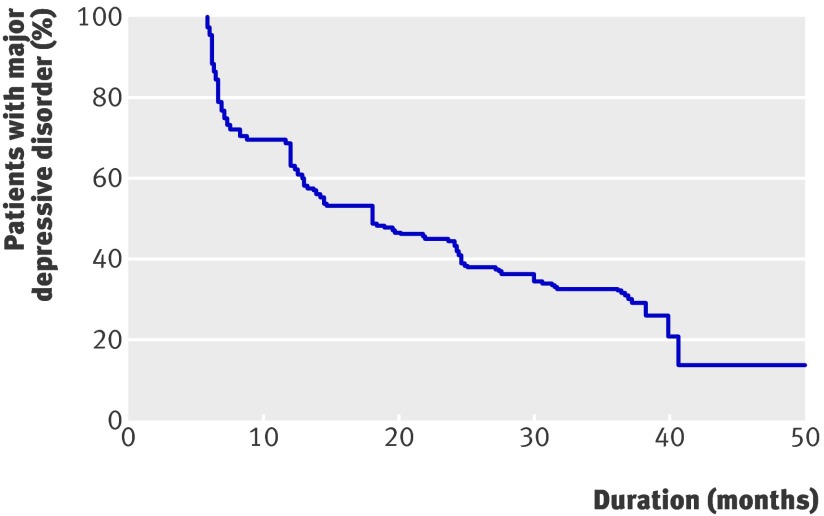

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan Meier curve for recovery in the 204 participants with at least one follow-up measurement. The mean time to recovery was 19.3 months (95% confidence interval 17.5 to 21.2), and the median time to recovery was 18.0 months (12.8 to 23.1). Overall, 35.1% (95% confidence interval 28.3% to 42.0%) of participants had recovered at one year, 60.4% (53.0% to 67.7%) at two years, and 68.1% (60.9% to 75.3%) at three years.

Fig 2 Survival curve of 204 patients aged 55 years or more with major depressive disorder in primary care

Predictors of prognosis

Univariable Cox survival analysis showed that eight variables were associated with time to recovery (P<0.20; table 2). As the Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale and primary care evaluation of mental disorders were both associated with the prognosis but were also highly correlated (Pearson’s r 0.5), only the scores on the primary care evaluation of mental disorders were used for the multivariable analyses as an indicator for severity of depression at baseline. In the best fitting multivariable model poor outcome was associated with more severe depression at baseline (primary care evaluation of mental disorders, range 0-9; hazard ratio 1.25, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.45), a family history of depression (1.45, 0.97 to 2.17), and less physical functioning (0.98, 0.97 to 0.99).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable Cox survival analyses for potential predictors of no recovery from major depressive disorder (n=204), measured at baseline, with follow-up for three years

| Characteristics | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years)* | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) | 0.143 | — | — | |

| Sex (women v men) | 1.06 (0.75 to 1.52) | 0.729 | — | — | |

| Education: | 0.325 | — | — | ||

| Middle v low | 1.28 (0.88 to 1.89) | 0.185 | — | — | |

| High v low | 0.95 (0.49 to 1.85) | 0.878 | — | — | |

| Living alone (yes v no)* | 1.32 (0.91 to 1.89) | 0.145 | — | — | |

| Comorbidity (somatic or psychiatric): | |||||

| Chronic somatic diseases | — | 0.408 | — | — | |

| 1 v 0 | 1.22 (0.72 to 2.04) | 0.463 | — | — | |

| ≥1 v 0 | 1.39 (0.85 to 2.27) | 0.191 | — | — | |

| Anxiety (yes v no)* | 1.28 (0.88 to 1.85) | 0.184 | — | — | |

| Cognitive dysfunction, MMSE score ≥24 v <24 | 1.35 (0.79 to 2.27) | 0.270 | — | — | |

| Depression: | |||||

| MÅDRS score (0-60)*† | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.08) | <0.001 | — | — | |

| PRIME-MD score (0-9)* | 1.22 (1.06 to 1.41) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.08 to 1.45) | 0.003 | |

| Family history (yes v no)* | 1.30 (0.88 to 1.92) | 0.185 | 1.45 (0.97 to 2.17) | 0.070 | |

| Early onset (<55 years)* | 1.30 (0.90 to 1.89) | 0.158 | — | — | |

| Treatment (yes v no) | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.57) | 0.617 | — | — | |

| Quality of life, PCS (0-100)* | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 0.055 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.008 | |

MMSE=mini-mental state examination score; MÅDRS=Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale; PRIME-MD=primary care evaluation of mental disorders; PCS=physical component scale of SF-36.

*P<0.20. These eight variables were associated with poor outcome in univariable analyses and therefore selected for multivariable analysis.

†MÅDRS and PRIME-MD were highly correlated. Therefore only PRIME-MD was used for the multivariable model.

Only 40% of the patients with depression were receiving treatment for depression at baseline—31% were taking antidepressants and 9% were referred to specialised mental health care (table 1). No association was found between treatment for depression (antidepressants or referral) and recovery. Patients receiving treatment, however, had more severe depression at baseline (mean difference in score on Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale 4.5; P<0.01).

Cognitive decline did not change during follow-up, and no difference was found between those who still had depression and those who had recovered (table 3). Only one patient dropped out during follow-up owing to serious cognitive decline and missed the last interview at three years. The prevalence of chronic diseases increased over time and was more common in the depressed group than in the recovered group. The depressed group showed a decline in daily functioning, but this did not seem to change in the recovered group. Finally, the number of patients receiving treatment for depression hardly changed during follow-up. At three years, only 37% of patients were being treated for their depression, compared with 24% in the recovered group. Only a few patients in both groups were referred to specialised mental health care, indicating that treatment for depression in late life is mainly carried out in primary care.

Table 3.

Longitudinal data on cohort of older (≥55 years) depressed patients compared with recovered patients with at least one measurement at follow-up, the Netherlands. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Baseline (n=204) | 1 year (n=185) | 2 years (n=169) | 3 years (n=160) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | 204 (100) | 120 (65) | 67 (40) | 51 (32) |

| Recovered | 0 | 65 (35) | 102 (60) | 109 (68) |

| Mean (SD) MÅDRS score (0-60): | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 19.3 (7.9) | 15.1 (7.6) | 17.8 (8.0) | 17.5 (7.1) |

| Recovered | — | 6.4 (4.2) | 7.9 (6.1) | 8.6 (6.2) |

| Anxiety: | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 68 (33) | 17 (14) | 13 (19) | 9 (18) |

| Recovered | — | 6 (9) | 6 (5) | 13 (12) |

| Mean (SD) MMSE score: | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 26.9 (2.6) | 27.1 (2.7) | 27.3 (2.6) | 27.3 (2.2) |

| Recovered | — | 27.7 (1.9) | 27.8 (2.2) | 27.2 (2.3) |

| Chronic illness | ||||

| Major depressive disorder: | ||||

| 0 | 28 (14) | 23 (19) | 11 (16) | 7 (14) |

| 1 | 59 (29) | 34 (28) | 17 (26) | 12 (23) |

| ≥1 | 117 (57) | 63 (53) | 39 (58) | 32 (63) |

| Recovered: | ||||

| 0 | — | 18 (28) | 15 (15) | 26 (24) |

| 1 | — | 20 (31) | 33 (32) | 24 (22) |

| ≥1 | — | 27 (41) | 54 (53) | 59 (54) |

| Mean (SD) functional limitations (0-100) | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 41.7 (13.1) | 40.3 (12.0) | 37.8 (12.5) | 37.2 (12.0) |

| Recovered | — | 44.0 (12.6) | 42.1 (11.3) | 43.0 (12.1) |

| Treatment for depression | ||||

| Major depressive disorder: | ||||

| None | 126 (62) | 84 (70) | 45 (67) | 32 (63) |

| Antidepressants | 61 (30) | 26 (22) | 19 (28) | 17 (33) |

| Referral | 17 (8) | 10 (8) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) |

| Recovered: | ||||

| None | — | 46 (71) | 79 (77) | 83 (76) |

| Antidepressants | — | 13 (20) | 20 (20) | 21 (19) |

| Referral | — | 6 (9) | 2 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Deaths | — | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 9 (4) |

MÅDRS=Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale; MMSE=mini-mental state examination.

Discussion

The prognosis for depression among older patients (≥55 years) in primary care is poor. The median duration of a major depressive episode was 18 months. Thirty five per cent had recovered within one year, 60% after two years, and 68% at three years.

A systematic review on the prognosis of depression in later life reported a poorer outcome in inpatients; only 13-18% had recovered after one year compared with 35% in our study.26 The researchers studied the prognosis of older patients who were admitted from the emergency room to medical services. A possible explanation for the difference is the higher prevalence of functional limitations among inpatients, which was also a predictor of poor clinical outcome in our study. The systematic review showed a better clinical outcome in hospital based studies. This might be due to better adherence to treatment.27 In our cohort only 40% of patients with a major depressive disorder were receiving treatment at baseline. This is less than the 45% found in the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study of adults with depression in the community,28 suggesting that a worse prognosis in older patients might be partly due to less adequate treatments.

Predictors of prognosis

Poor outcome was associated with the severity of the index episode, a family history of depression, and functional decline. Previous community studies on depression in later life also found evidence of an association between these variables and the prognosis for depression.12 These clinical factors are all available in routine practice and could therefore be used to help decide on the aggressiveness of treatment. Our data showed that functional limitations increased over the three years of follow-up in the group with chronic depression but not in those who had recovered. This finding agrees with those of another study29 and underlines the importance of chronic depression as a disabling illness. More research is needed on this longitudinal association.

Whether there is an association between depression in later life and cognitive decline is debatable. Some researchers have found evidence for an association30 31 32 and others not.33 34 35 The present study did not provide evidence either at baseline (table 2) or during follow-up (table 3).

Only a small proportion of patients with depression were being treated at baseline and during follow-up. This was also found in previous studies.29 36 We found no association between treatment for depression and the prognosis. Patients who were receiving treatment, however, had more severe depression at baseline (mean difference in score on Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale 4.5), suggesting confounding by indication.

It is likely that the prognosis of depression in later life is determined by many factors, at least some of which are inter-related. Therefore any definitive statement about causal inference or confounding would be premature. We provided data on factors that predict the prognosis, controlling for their inter-relatedness. This is highly relevant for clinical practice, as it identifies those with the highest risk of a poor prognosis.

Strengths and limitations

We used both diagnostic and dimensional data ascertained at multiple time points during follow-up to study the course of major depressive disorder in a large cohort of older patients in primary care. These strengths, together with follow-up for three years and access to several putative prognostic factors, allowed a thorough assessment of the prognosis of depression in later life.

Our study did, however, have some limitations. We included a sample of older patients with depression in day to day clinical practice, and consequently included those with existing depression. As depression has a variable prognosis, this sampling strategy may have led to over-representation of patients with persistent long term depression. The alternative strategy would have been to include patients without depression and to follow them up, concentrating on those with incident depression. However, this was precluded because of the large sample that would be needed at baseline and the long follow-up required to build the necessary cohort. The present results are generaliseable to a cross section of patients with depression, as the condition is present at any time in general practice, but might overestimate chronicity because of the sampling of prevalent cases.

We screened consecutive patients aged 55 years and older who visited their doctor, regardless of the reason for consultation. As these patients were able to come to the practice and 98% were living independently, they were a selection of the more healthy older population. Furthermore, those lost to the analyses throughout the study were older. Although age was not associated with prognosis (table 2), it can be assumed that older patients might be frailer and more at risk of functional limitations. Given that functional limitations are a predictor for poor clinical outcome, our results may be an underestimation of the true course of depression owing to attrition of the frailest patients during follow-up.

We assessed prognosis every six months. Using an interval of six months to assess patients may have led to an overestimation of the duration of depression because patients might have recovered earlier. We did not, however, have access to data on the duration of the index episode at inclusion. This has the effect of systematically underestimating the true duration of episodes and counteracts the potential overestimation. The advantage of Cox survival analyses is that we used data on respondents with more than one measurement. However, in those respondents who missed interviews, either the follow-up was less than three years or the interval between measurements was more than six months, which may have led to bias. For example, the interval between assessments for a respondent who missed the third assessment was 12 months. During this period the patient could have recovered, leading to a potential overestimation of time to recovery. Those with fewer than four measurements were older and had a lower level of education than those with more measurements. Both variables were not associated with the outcome.

Our design was observational, providing an insight into the clinical course of depression without intervening with structured treatment protocols. This makes the results representative of the population seen by general practitioners. Assuming that treatment is not harmful to most patients, the effect of our naturalistic design would be to underestimate the true clinical course of depression among older patients.

We only had access to self reported data on treatment for depression. It is possible that the doctors prescribed more antidepressants or referred more patients to specialised mental health care than was reported, owing to non-adherence of the patients. The advantage of self reporting treatment is that we are more likely to have collected data on actual treatment received by patients.

Conclusion

Our results support our hypothesis that the prognosis of depression in later life in primary care would be poor. One possible explanation for this is inadequate treatment in older patients with depression, as most (60% of patients with major depressive disorder at baseline, 71-77% during follow-up) did not receive any treatment for their condition. Analyses of data on patients with undetected depression during the first year of follow-up showed a poor prognosis; depression was still present in 67% of these patients after one year.10 Identifying patients with depression at high risk of a poor outcome can help to improve treatment and therefore prognosis. We found that a poor outcome was predicted by clinical factors that should be readily available in routine practice. If confirmed in other studies, these factors could be incorporated in professional guidelines, helping clinicians to identify older patients needing earlier, better integrated, and more aggressive treatment. Finally, research is needed to learn more about the longitudinal association between depression and functional limitations.

What is already known on this topic

Depression in later life is common in primary care and has an enormous impact on wellbeing and functioning

What this study adds

Depression in patients aged 55 or more in primary care has a poor prognosis

Identified prognostic factors (for example, severity of the index episode, a family history of depression, and functional decline) are readily available in clinical practice and could help direct treatment to those at highest risk of a poor prognosis

We thank the respondents for their participation.

Contributors: EL-S carried out the study, did the analyses, and wrote the paper. HvM and AB had the original idea for the study, designed the study, obtained the grants, helped in the analyses and interpretation of the data, supervised the project, and cowrote the paper. TH and JT assisted with the analyses and interpretation of the data and cowrote the paper. MdH supervised the project and cowrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. EL-S and HvM are guarantors.

Funding: The data reported on were collected in the context of the West Friesland Study, which was financed by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (grant No 2200.0019) and the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (MW grant 904.57.127).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the VU University Medical Centre.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:a3079

References

- 1.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1989;262:914-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bremmer MA, Hoogendijk WJ, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, Schalk BW, Beekman AT. Depression in older age is a risk factor for first ischemic cardiac events. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:523-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1069-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W, Beekman AT. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:889-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Voellinger R, Santos-Eggimann B. Healthcare and preventive services utilization of elderly Europeans with depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 2008;105:247-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew-Graham CA, Lovell K, Roberts C, Baldwin R, Morley M, Burns A, et al. A randomised controlled trial to test the feasibility of a collaborative care model for the management of depression in older people. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:364-70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2836-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:299-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Licht-Strunk E, Beekman ATF, de Haan M, van Marwijk HWJ. The prognosis of undetected depression in older general practice patients. A one year follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2008; Jul 14 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gilchrist G, Gunn J. Observational studies of depression in primary care: what do we know? BMC Fam Pract 2007;8:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Licht-Strunk E, Windt DAWM, van Marwijk HWJ, de Haan M, Beekman ATF. The prognosis of depression in older patients in general practice and the community. A systematic review. Fam Pract 2007;24:168-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Licht-Strunk E, van der Kooij KG, van Schaik DJ, van Marwijk HW, van Hout HP, de Haan M, et al. Prevalence of depression in older patients consulting their general practitioner in the Netherlands. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:1013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh JI YJ. Geriatric depression scale: recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165-72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP. The short form of the geriatric depression scale: a comparison with the 30-item form. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1991;4:173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, III, Hahn SR, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Marwijk H, Grundmeijer H, Bijl D, van Gelderen M, de Haan M, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Dutch College of General Practitioners Guideline Depression, first revision [NHG-Standaard Depressieve stoornis (depressie). Eerste herziening. In Dutch]. Huisarts Wet 2003;46:614-33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. J Affect Disord 2002;72:177-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1407-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafonek S, Ettinger WH, Roca R, Kittner S, Taylor N, German PS. Instruments for screening for depression and dementia in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health diagnostic interview schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Koskinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental summary scales: a users’ manual, 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Health Institute, 1994.

- 25.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole MG, McCusker J, Ciampi A, Windholz S, Latimer E, Belzile E. The prognosis of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:966-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole MG, Bellavance F. The prognosis of depression in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;5:4-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spijker J, de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Beekman AT, Ormel J, Nolen WA. Duration of major depressive episodes in the general population: results from The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:208-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenze EJ, Schulz R, Martire LM, Zdaniuk B, Glass T, Kop WJ, et al. The course of functional decline in older people with persistently elevated depressive symptoms: longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raji MA, Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo YF, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ. Depressive symptoms and cognitive change in older Mexican Americans. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2007;20:145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojo F, Al Snih S, Ray LA, Raji MA, Markides KS. History of fractures as predictor of subsequent hip and nonhip fractures among older Mexican Americans. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:412-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stimpson JP, Kuo YF, Ray LA, Raji MA, Peek MK. Risk of mortality related to widowhood in older Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:313-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beekman AT, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, Smit JH, Schoevers RS, de Beurs E, et al. The natural history of late-life depression: a 6-year prospective study in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:605-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsell Y, Jorm AF, Winblad B. The outcome of depression and dysthymia in a very elderly population: Results from a three-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health 1998;2:100-4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulberg HC, Mulsant B, Schulz R, Rollman BL, Houck PR, Reynolds CF, III. Characteristics and course of major depression in older primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998;28:421-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verhaak PF. Analysis of referrals of mental health problems by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 1993;43:203-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]