Abstract

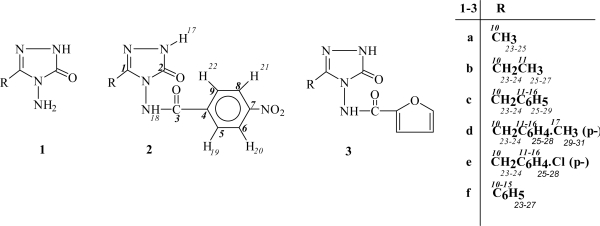

Six novel 3-alkyl(aryl)-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5- ones (2a-f) were synthesized by the reactions of 3-alkyl(aryl)-4-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H- 1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (1a-f) with p-nitrobenzoyl chloride and characterized by elemental analyses and IR, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and UV spectral data. The newly synthesized compounds 2 were titrated potentiometrically with tetrabutylammonium hydroxide in four non-aqueous solvents such as acetone, isopropyl alcohol, tert-butyl alcohol and N,N-dimethylformamide, and the half-neutralization potential values and the corresponding pKa values were determined for all cases. Thus, the effects of solvents and molecular structure upon acidity were investigated. In addition, isotropic 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic shielding constants of compounds 2 were obtained by the gauge-including-atomic-orbital (GIAO) method at the B3LYP density functional level. The geometry of each compound has been optimized using the 6-311G basis set. Theoretical values were compared to the experimental data. Furthermore, these new compounds and five recently reported 3-alkyl-4-(2-furoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (3a–c,e,f) were screened for their antioxidant activities.

Keywords: 4,5-Dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones; Acylation; Density functional calculations; GIAO; Antioxidant activity; pKa; Potentiometric titrations

Introduction

1,2,4-Triazole and 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives are reported to show a broad spectrum of biological activities [1–6], and several papers have devoted with the synthesis of acyl derivatives of 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives [2,4,7–12]. In addition, it is known that 1,2,4-triazole and 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one rings have weak acidic properties, so that some 1,2,4-triazole and 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives were titrated potentiometrically with tetrabutylammonium hydroxide in non-aqueous solvents, and the pKa values of the compounds were determined [2,13,14]. We have previously described the synthesis and potentiometric titrations of some new 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives in different non-aqueous medium [9–12,15–18], where we determined the pKa values of these compounds for each non-aqueous solvent.

NMR spectroscopy has proved to be an exceptional tool to elucidate structure and molecular conformation. Ab initio and DFT (density functional theory) calculations of NMR shielding constants at very accurate levels of theory are available at literature [19]. The widely used methods to calculate chemical shifts are as follows: IGLO (individual gauge localized orbital), LORG (localized or loacaorbital origin) and GIAO (gauge independent or invariant or including atomic orbital). The GIAO approach [20] is known to give satisfactory chemical shifts for different nuclei [20–22] of larger molecules, yet these quantum chemical calculations often have to be limited to isolated (gas-phase) molecules and in some preferred (optimized) structures, while experimental NMR spectra are commonly statically averages affected by dynamic process such as conformational equilibria as well as intra and/or intermolecular interactions. We have previously described the synthesis and GIAO NMR calculations for some new 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives [23,24].

Antioxidants are extensively studied for their capacity to protect organisms and cells from damage that is induced by oxidative stress. Scientists in various disciplines have become more interested in new compounds, either synthesized or obtained from natural sources that could provide active components to prevent or reduce the impact of oxidative stress on cells [25]. Exogenous chemicals and endogenous metabolic processes in human body or in food system might produce highly reactive free radicals, especially oxygen derived radicals, which are capable of oxidizing biomolecules, resulting in cell death and tissue damage. Oxidative damages play a significantly pathological role in human diseases. For example, cancer, emphysema, cirrhosis, atherosclerosis and arthritis have all been correlated with oxidative damage. Also, excessive generation of ROS (reactive oxygen species) induced by various stimuli and which exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the organism leads to variety of pathophysiological processes such as inflammation, diabetes, genotoxicity and cancer [26]. In the present study, due to a wide range applications and to find their possible radical scavenging and antioxidant activity, the newly synthesized compounds were investigated using several antioxidant methodologies: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging, reducing power and metal chelating activities.

The antioxidant activity of six new 3-alkyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5- ones (2a–f) (Scheme 1), which were synthesized by the reactions of 3-alkyl-4-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (1a-f) with p-nitrobenzoyl chloride and five 3-alkyl-4-(2-furoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (3a–c,e,f), which was synthesized according to literature [10] were determined. In addition, a DFT method was used to calculate theoretical 1H and 13C data of six new 2 type compounds. Moreover, we also examined the potentiometric titrations of the synthesized type 2 compounds with tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAH) in four non-aqueous solvents (acetone, isopropyl alcohol, tert-butyl alcohol and N,N-dimethylformamide) to determine the corresponding half-neutralization potentials (HNP) and the corresponding pKa values. The data obtained from the potentiometric titrations was interpreted, and the effect of the C-3 substituent in 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one ring as well as solvent effects were determined similarly to previous studies [9–18].

Scheme 1.

Experimental

Synthesis

IR spectra were registered using potassium bromide disks on a Shimadzu 408 spectrometer. 1HNMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded in deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide with TMS as internal standard on a Varian-Mercury spectrometer at 200 MHz and 50 MHz, respectively. UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured for ethanol solutions in 10 mm quartz cells between 200 and 400 nm using a Shimadzu-1201 spectrophotometer. Melting points were taken on an Electrothermal 9100 digital melting point apparatus. Combustion analyses were performed on a Carlo Erba 1106 Elemental Analyzer. Chemicals were supplied from Fluka and Merck. The starting compounds 1a–f were prepared according to literature [8,27]. Compounds 3 were obtained throught recently reported methods [10].

General Method for the Preparation of 3-Alkyl(aryl)-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4- triazol-5-ones (2)

3-Alkyl(aryl)-4-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (1) (0.01 mol) was heated with 1.86 g (0.01 mol) of p-nitrobenzoyl chloride at 150–160 ºC for 1.5 h and cooled. Recrystallization of the crude product from an appropriate solvent gave pure compound 2.

3-Methyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2a). White crystals, yield 84 %; m.p. 259–60 °C (EtOH/water, 1:2); Calculated for C10H9N5O4: 45.6% C, 3.4 % H, 26.6% N; found: 45.0% C, 3.3% H, 26.6% N; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ; 2.48 (s, 3H, CH3), 8.54 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J=8.6 Hz), 8.72 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J=8.2 Hz), 12.18 (s, 2H, 2NH). 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.79 (CH3), 124.24 (2C), 129.70 (2C), 136.69, 145.45 (aromatic carbons), 150.20 (triazole C3), 153.45 (triazole C5), 164.97 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3395 (NH), 1745, 1687 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 820 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 254 (10020), 214 (7920) nm.

3-Ethyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2b). White crystals, yield 84 %; m.p. 238–240 °C (EtOH-water, 1:2); Calculated for C11H11N5O4: 47.7% C, 4.0% H, 25.3% N; found: 48.2% C, 4.0% H, 25.5% N; 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.07 (CH3), 18.22 (CH2), 124.15 (2C), 129.64 (2C), 136.85, 149.60 (aromatic carbons), 150.30 (triazole C3), 153.80 (triazole C5), 165.10 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3300, 3100 (NH), 1720, 1685 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 800 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 251 (10550), 213 (8590) nm.

3-Benzyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2c). White crystals, yield 84 %; m.p. 255–257 °C (EtOH-toluene, 1:3); Calculated for C16H13N5O4: 56.6% C, 3.9% H, 20.6% N; found: 56.4% C, 3.9% H, 20.1% N; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 3.89 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.29 (s, 5H, Ar-H), 8.14 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 7.9 Hz), 8.40 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 7.9 Hz), 11.80 (s, 1H, NH), 12.01 (s, 1H, NH); 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 31.40 (CH2), 124.06 (2C), 127.17, 128.77 (2C), 129.08 (2C), 129.59 (2C), 135.03, 136.69, 147.19 (aromatic carbons), 150.05 (triazole C3), 153.10 (triazole C5), 164.73 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3275, 3150 (NH), 1730, 1680 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 810 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring), 770, 710 (monosubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 258 (11010), 214 (11010) nm.

3-p-Methylbenzyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2d). White crystals, yield 89 %; m.p. 238–239 °C (EtOH-water, 1:2); Calculated for C17H15N5O4: 57.8% C, 4.3% H, 19.8% N; found: 58.3% C, 4.1% H, 19.7% N; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.27 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.80 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.13 (s, 4H, Ar-H), 8.14 (s, 2H, Ar-H), 8.41 (s, 2H, Ar-H), 11.74 (s, 1H, NH), 11.94 (s, 1H, NH); 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 20.39 (CH3), 30.40 (CH2), 123.64 (2C), 128.46 (2C), 128.84 (2C), 129.10 (2C), 131.60, 135.90, 136.20, 146.85 (aromatic carbons), 149.70 (triazole C3), 152.75 (triazole C5), 164.30 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3300, 3150 (NH), 1730, 1680 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 815 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 258 (13860), 214 (13860) nm.

3-p-Chlorobenzyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2e). White crystals, yield 88 %; m.p. 246–247 °C (EtOH-water, 1:2); Calculated for C16H12N5O4Cl: 51.4% C, 3.2% H, 18.7% N; found: 52.2% C, 3.2% H, 18.7% N; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 4.07 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.45–7.54 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 8.31 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 8.6 Hz), 8.58 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 8.2 Hz), 11.94 (s, 1H, NH), 12.19 (s, 1H, NH); 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 30.60 (CH2), 124.12 (2C), 128.73 (2C), 129.64 (2C), 131.01 (2C), 132.10, 134.20, 136.60, 146.80 (aromatic carbons), 150.20 (triazole C3), 153.10 (triazole C5), 164.80 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3275, 3150 (NH), 1725, 1680 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 820 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 252 (11590), 213 (9380) nm.

3-Phenyl-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (2f). White crystals, yield 82 %; m.p. 247–248 °C (EtOH-water, 1:2); Calculated for C15H11N5O4: 55.4% C, 3.4% H, 21.5% N; found: 55.2% C, 3.5% H, 21.3% N; 1H-NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6): λ 7.53–7.62 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.80–7.88 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 8.21 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 7.3 Hz), 8.44 (d, 2H, Ar-H; J= 7.9 Hz), 12.19 (s, 1H, NH), 12.48 (s, 1H, NH); 13C-NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6): λ 124.30 (2C), 126.91 (2C), 129.24 (2C), 129.46 (2C), 131.10, 131.90, 136.40, 146.10 (aromatic carbons), 150.25 (triazole C3), 153.40 (triazole C5), 164.80 (C=O); IR (KBr): 3275, 3225 (NH), 1745, 1695 (C=O), 1610 (C=N), 820 (1,4-disubstituted benzenoid ring), 775, 700 (monosubstituted benzenoid ring) cm−1; UV (ethanol) λmax (ε, L mol−1 cm−1): 263 (17500), 222 (8160) nm.

Antioxidant Activity

Chemicals

Butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT) was purchased from E. Merck. Ferrous chloride, α-tocopherol, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH.), 3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-bis(phenyl-sulfonic acid)-1,2,4-triazine (ferrozine), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and trichloracetic acid (TCA) were purchased from Sigma (Sigma −Aldrich GmbH, Sternheim, Germany).

Reducing power

The reducing power of the synthesized compounds was determined according to the method of Oyaizu [28]. Different concentrations of the samples (50–150 mg/L) in DMSO (1 mL) were mixed with phosphate buffer (2.5 mL, 0.2 M, pH = 6.6) and potassium ferricyanide (2.5 mL, 1%). The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 20 min. after incubation period; a portion of trichloroacetic acid (2.5 mL, 10%) was added to the mixture, which was then centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 x g. The upper layer of solution (2.5 mL) was mixed with distilled water (2.5 mL) and FeCl3 (0.5 mL, 0.1%), and then, the absorbance was measured at 700 nm in a spectrophometer. Higher absorbance of the reaction mixture indicated greater reducing power.

Free radical scavenging activity

Free radical scavenging activity of compounds was measured by DPPH. using the method of Blois [29]. Briefly, a 0.1 mM solution of DPPH. in ethanol was prepared, and this solution (1 mL) was added to the solutions in DMSO (3 mL) at different concentrations (50–150 mg/L). The mixture was shaken vigorously and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min. Then the absorbance was measured at 517 nm in a spectrophometer. Lower absorbance of the reaction mixture indicated higher free radical scavenging activity. The DPPH. concentration (mM) in the reaction medium was calculated from the following calibration curve and determined by linear regression (R: 0.997):

| (1) |

The capability to scavenge the DPPH radical was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

Where A0 is the absorbance of the control reaction and A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the samples or standards.

Metal chelating activity

The chelating ferrous ions by the synthesized compounds and standards were estimated by the method of Dinis et al. [30]. Briefly, the synthesized compounds (12.5–37.5 mg/L) were added to a solution of 2 mM FeCl2 (0.05 mL). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 mM ferrozine (0.2 mL) and the mixture was shaken vigorously and left standing at room temperature for 10 min. after the mixture had reached equilibrium, the absorbance of the solution was then measured spectrophotometrically at 562 nm in a spectrophotometer. All test and analyses were run in triplicate and averaged. The percentage of inhibition of ferrozine-Fe2+ complex formation was given by the formula:

| (3) |

Where A0 is the absorbance of the control, and A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the samples or standards. The control did not contain compound or standard.

HNP and pKa value determination

A Jenway 3040-model ion analyzer was used for potentiometric titrations. An Ingold pH electrode was used. For each compound that would be titrated, the 0.001 M solution was separately prepared in each non-aqueous solvent. The 0.05 M solution of TBAH in isopropyl alcohol, which is widely used in the titration of acids, was used as titrant. The mV values, that were obtained in pH-meter, were recorded. Finally, the HNP values were determined by drawing the mL (TBAH)-mV graphic.

Computational Methods

The compounds, for which calculations were carried out, are indicated in Tables 2–7. The numbering system is shown in Scheme 1. All the structures were fully optimized with the Gaussian 03 program at the B3LYP/6-311G theoretical level [31]. After the optimization, 1H and 13C chemical shifts were calculated with GIAO method [20,32–34], using corresponding TMS shielding calculated at the same theoretical level as the reference. All the computations were done using an IBM X-225 e-server computer. Linear correlation analyses were carried out using SigmaPlot program. The quality of each correlation was judged examining R, the Pearson correlation coefficient [35].

Table 2.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2a.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 150,20 | 156,96 | −6,76 |

| C-2 | 153,45 | 158,05 | −4,60 |

| C-3 | 164,97 | 177,79 | −12,82 |

| C-4 | 136,69 | 144,73 | −8,04 |

| C-5 | 129,70 | 138,10 | −8,40 |

| C-6 | 124,24 | 130,54 | −6,30 |

| C-7 | 145,45 | 159,39 | −13,94 |

| C-8 | 124,24 | 130,36 | −6,12 |

| C-9 | 129,70 | 133,10 | −3,40 |

| C-10 | 10,79 | 13,78 | −2,99 |

| H-17 | 12,18 | 6,94 | 5,24 |

| H-18 | 12,18 | 7,02 | 5,16 |

| H-19 | 8,54 | 8,21 | 0,33 |

| H-20 | 8,72 | 8,53 | 0,19 |

| H-21 | 8,72 | 8,52 | 0,20 |

| H-22 | 8,54 | 7,89 | 0,65 |

| H-23 | 2,48 | 2,29 | 0,19 |

| H-24 | 2,48 | 2,05 | 0,43 |

| H-25 | 2,48 | 2,70 | −0,22 |

Table 7.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2f.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 150,25 | 160,11 | −9,86 |

| C-2 | 153,40 | 158,42 | −5,02 |

| C-3 | 164,80 | 180,64 | −15,84 |

| C-4 | 136,40 | 145,42 | −9,02 |

| C-5 | 129,46 | 137,88 | −8,42 |

| C-6 | 124,30 | 130,48 | −6,18 |

| C-7 | 146,10 | 159,42 | −13,32 |

| C-8 | 124,30 | 130,13 | −5,83 |

| C-9 | 129,46 | 133,65 | −4,19 |

| C-10 | 131,90 | 133,46 | −1,56 |

| C-11 | 129,24 | 135,55 | −6,31 |

| C-12 | 126,91 | 134,59 | −7,68 |

| C-13 | 131,10 | 137,45 | −6,35 |

| C-14 | 126,91 | 134,92 | −8,01 |

| C-15 | 129,24 | 136,19 | −6,95 |

| H-17 | 12,48 | 7,28 | 5,20 |

| H-18 | 12,19 | 6,78 | 5,41 |

| H-19 | 8,21 | 8,27 | −0,06 |

| H-20 | 8,44 | 8,53 | −0,09 |

| H-21 | 8,44 | 8,51 | −0,07 |

| H-22 | 8,21 | 8,01 | 0,20 |

| H-23 | 7,88 | 8,04 | −0,16 |

| H-24 | 7,53 | 7,44 | 0,09 |

| H-25 | 7,62 | 7,50 | 0,12 |

| H-26 | 7,57 | 7,46 | 0,11 |

| H-27 | 7,80 | 7,76 | 0,04 |

Results and Discussion

In this study, the compounds 2 and 3 were screened for their in-vitro antioxidant activities. Several methods are used to determine antioxidant activities. The methods used in this study are given below.

Total reductive capability using the potassium ferricyanide reduction method

The reductive capabilities of compounds are assessed by the extent of conversion of the Fe3+ / ferricyanide complex to the Fe2+/ ferrous form. The reducing powers of the compounds were observed at different concentrations, and results were compared with BHA, BHT and α-tocopherol. The reducing capacity of a compound may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity [36]. The antioxidant activity of putative antioxidant has been attributed to various mechanisms, among which are prevention chain initiation, binding of transition metal ion catalyst, decomposition of peroxides, prevention of continued hydrogen abstraction, reductive capacity and radical scavenging [37]. In this study, all of the amounts of the compounds showed lower absorbance then blank. Hence, no activities were observed to reduce metal ions complexes to their lower oxidation state or to take part in any electron transfer reaction. In order words, compounds 2a–f and 3a–c,e,f did not show the ability of electron donor to scavenge free radicals.

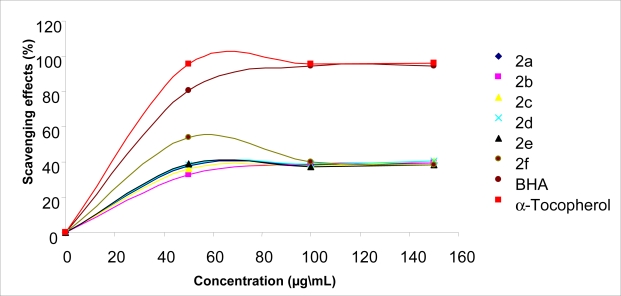

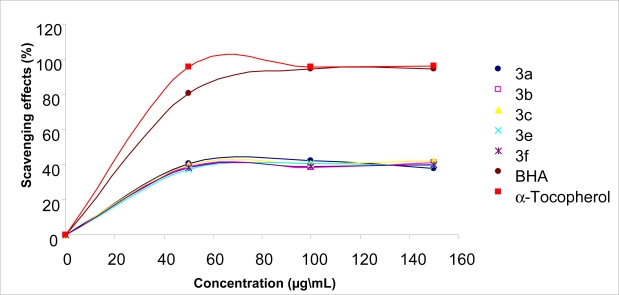

DPPH• radical scavenging activity

The scavenging the stable DPPH radical model is a widely used method to evaluate antioxidant activities in a relatively short time compared with other methods. The effect of antioxidants on DPPH radical scavenging was thought to be due to their hydrogen donating ability [38]. DPPH is a stable free radical and accepts an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule [39]. The reduction capability of DPPH radicals was determined by decrease in its absorbance at 517 nm induced by antioxidants. The absorption maximum of a stable DPPH radical in ethanol was at 517 nm. The decrease in absorbance of DPPH radical caused by antioxidants, because of reaction between antioxidant molecules and radical, progresses, which result in the scavenging of the radical by hydrogen donation. It is visually noticeable as a discoloration from purple to yellow. Hence, DPPH. is usually used as a substrate to evaluate antioxidative activity of antioxidants [40]. In this study, antiradical activities of compounds and standard antioxidants such as BHA and α-tocopherol were determined by using DPPH. method. All the compounds tested with this method showed lower absorbance than absorbance of the control reaction and higher absorbance than that of the standard antioxidant reactions. The data obtained in this study indicate that the newly synthesized compounds showed mild activities as a radical scavenger, indicating that it has moderate activities as hydrogen donors. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate a dose-dependent DPPH· radical scavenging activity of compounds tested and standards.

Figure 1.

Free radical scavenging activity of compounds 2a–f, BHA and α-tocopherol measured using DPPH at different concentrations (50–100–150 mg/L).

Figure 2.

Free radical scavenging activity of compounds 3a–c,e,f, BHA and α-tocopherol measured using DPPH at different concentrations (50–100–150 mg/L).

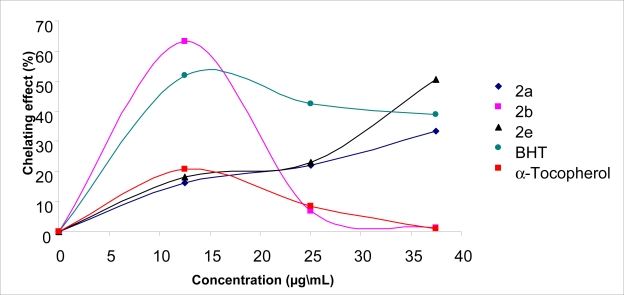

Ferrous ions chelating activity

The chelating effect towards ferrous ions by the compounds and standards was determined according to the method of Dinis [30]. Ferrozine can quantitatively form complexes with Fe2+. In the presence of chelating agents, the complex formation is disrupted with the result that the red colour of the complex is decreased. Measurement of colour reduction therefore allows estimation of the chelating activity of the coexisting chelator [41]. Transition metals have pivotal role in the generation oxygen free radicals in living organism. The ferric iron (Fe3+) is the relatively biologically inactive form of iron. However, it can be reduced to the active Fe2+, depending on condition, particularly pH [42] and oxidized back through Fenton type reactions with the production of hydroxyl radical or Haber-Weiss reactions with superoxide anions. The production of these radicals may lead to lipid peroxidation, protein modification and DNA damage. Chelating agents may not activate metal ions and potentially inhibit the metal-dependent processes [43]. Also, the production of highly active ROS such as O2.–, H2O2 and OH. is also catalyzed by free iron though Haber-Weiss reactions:

| (4) |

Among the transition metals, iron is known as the most important lipid oxidation pro-oxidant, due to its high reactivity. The ferrous state of iron accelerates lipid oxidation by breaking down the hydrogen and lipid peroxides to reactive free radicals via the Fenton reactions:

| (5) |

Also Fe3+ ion produces radicals from peroxides, although the rate is tenfold less than of Fe2+ ion, which is the most powerful pro-oxidant among various sort of metal ions [44].

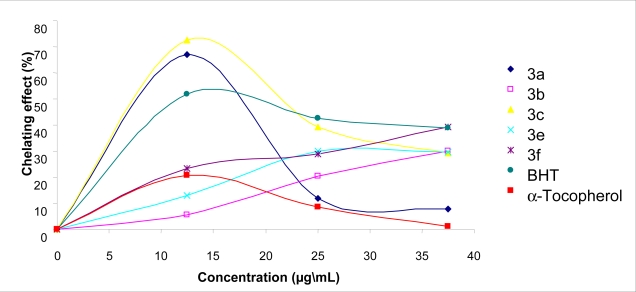

Ferrous ion chelating activities of 2a, 2b and 2e, BHT and α-tocopherol are shown in Figure 3. 2a showed better ferrous chelating activity compared to standards at a concentration of 12,5 mg/L. Compounds 2a and 2e revealed good chelating activities at a concentration of 37,5 mg/L. Compounds 2c, 2d and 2f did not show any chelating effect. The 3a, 3b, 3c, 3e and 3f compounds tested with this method exhibited 66.9, 5.4, 72.4, 12.9 and 23.5 % chelation of ferrous ion at the concentration of 12.5 mg/L, respectively (Figure 4). Otherwise, the percentages of metal chelating capacity of same concentration of BHT and α-tocopherol were found 51,8 and 12,5 %, respectively (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Metal chelating capacity was significant since it reduced the concentrations of the catalyzing transition metal. It was reported that chelating agents, which form σ-bonds with a metal, are effective as secondary antioxidants because they reduce the redox potential thereby stabilizing the oxidized form of metal ion [45]. The data obtained from Figure 3 and Figure 4 reveal that the compounds, except for 2c, 2d and 2f, demonstrate a marked capacity for iron binding at the concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that their action as peroxidation protector may be related to its iron binding capacity. Moreover, free iron is known to have low solubility and a chelated iron complex has greater solubility in solution, which can be contributed solely from the ligand. Furthermore, the compound-iron complex may also be active, since it can participate to iron-catalyzed reactions.

Figure 3.

Metal chelating effect of different amount of the 2a, 2b, 2e, BHT and α-tocopherol on ferrous ions.

Figure 4.

Metal chelating effect of different amount of the 3a, 3b, 3c, 3e, 3f, BHT and α-tocopherol on ferrous ions.

In this study, the antioxidant activities of compounds varied with the tree test models. Our results revealed that all of the tested compounds showed mild antiradical activity and the compounds, except for 2c, 2d and 2f, revealed good chelating activities. In conclusion the data here reported could be of the possible interest because of their activities of radical scavenging and metal chelating could prevent redox cycling.

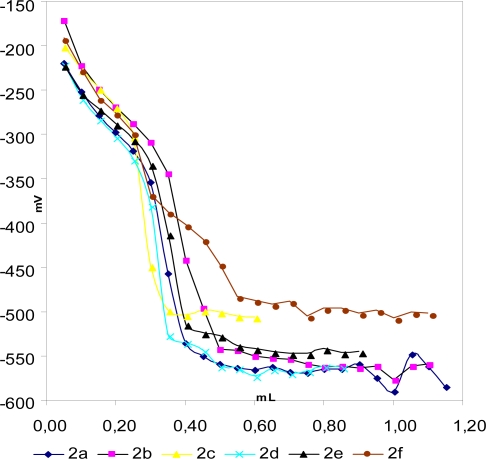

Potentiometric titrations

As a separate study, newly synthesized 2a–f type compounds were titrated potentiometrically with tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAH) in four non-aqueous solvents such as acetone (ε=20.6), isopropyl alcohol (ε=19.4), tert-butyl alcohol (ε=12.0) and N,N-dimethylformamide (ε=36.7). The mV values read in each titration were drawn against 0.05 M TBAH volumes (mL) added, and thus potentiometric titration curves were formed for all the cases. From these curves, the HNP values were measured, and the corresponding pKa values were calculated.

As an example, the potentiometric titration curves for 0.001 M compounds 2a–f solutions titrated with 0.05 M TBAH in acetone are shown Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Potentiometric titration curves of 0.001 M solutions of compound 2a–2f titrated with 0.05 M TBAH in acetone at 25°C.

The HNP values and the corresponding pKa values for new compounds 2a–f, obtained from the potentiometric titrations with 0.05 M TBAH in acetone, isopropyl alcohol, tert-butyl alcohol and N,Ndimethylformamide, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The HNP and the corresponding pKa values of compounds 2a–f in isopropyl alcohol, tert-butyl alcohol, acetone and N,N- dimethylformamide.

| Compd. | N,N-Dimethyl formamide | Acetone | Isopropyl alcohol | tert-butyl alcohol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP (mV) | pK a | HNP (mV) | pK a | HNP (mV) | pK a | HNP (mV) | pK a | |

| 2a | −218 | 11.02 | −279 | 12.44 | −119 | 9.46 | −168 | 10.36 |

| 2b | −200 | 10.68 | −282 | 12.43 | −119 | 9.46 | −212 | 11.06 |

| 2c | −241 | 11.67 | −237 | 11.46 | −163 | 9.76 | −253 | 11.80 |

| 2d | −152 | 10.15 | −279 | 12.44 | −156 | 9.90 | −267 | 12.05 |

| 2e | −218 | 11.23 | −242 | 11.72 | −133 | 9.28 | −183 | 10.51 |

| 2f | −237 | 11.41 | −259 | 12.08 | −191 | 10.43 | −172 | 10.46 |

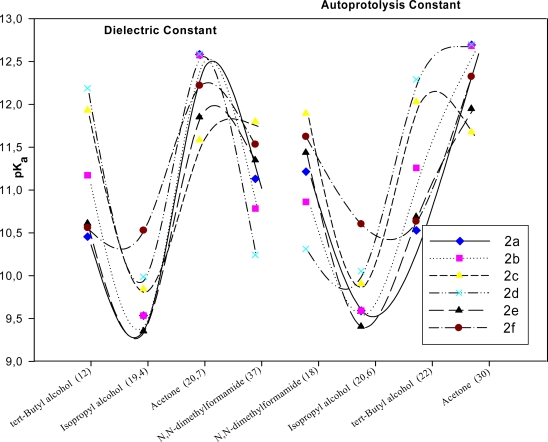

When the dielectric permittivity of solvents is taken into consideration, the acidic arrangement can be expected as follows: N,N-dimethylformamide (ε=36.7) > acetone (ε=20.6) > isopropyl alcohol (ε=19.4) > tert-butyl alcohol (ε=12.0). As seen in Table 1, the acidic arrangement for compounds 2a, 2e and 2f is: isopropyl alcohol > tert-butyl alcohol > N,N-dimethylformamide > acetone, and for compounds 2b and 2d, it is : isopropyl alcohol > N,N-dimethylformamide > tert-butyl alcohol > acetone while the arrangement for compound 2c is : isopropyl alcohol > acetone > N,N-dimethylformamide > tert-butyl alcohol. In isopropyl alcohol, all these compounds show the strongest acidic properties, but they show the weakest acidic properties in acetone (for compound 2c in tert-butyl alcohol). This situation may be attributed to the hydrogen bonding between the negative ions formed and the solvent molecules in the amphiprotic neutral solvents.

The degree to which a pure solvent ionizes was represented by its autoprotolysis constant, KHS.

| (6) |

For the above reaction the constant is defined by

| (7) |

Autoprotolysis is an acid-base reaction between identical solvent molecules is which some act as an acid and others as a base. Consequently, the extent of an autoprotolysis reaction depends both on the intrinsic acidity and the instrinsic basicity of the solvent. The importance of the autoprotolysis constant in titrations lies in its effect on the completeness of a titration reaction [46]. The exchange of the pKa values with autoprotolysis constant and dielectric constant are given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The variation of the pKa values for synthesized componds 2a–f with autoprotolysis constant and dielectric constant of the solvent.

As it is well known, the acidity of a compound depends on some factors. The two most important factors are the solvent effect and molecular structure [9–18]. Table 1 shows that the HNP values and corresponding pKa values obtained from the potentiometric titrations depend on the non-aqueous solvents used and the substituents at C-3, in 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one ring.

Theoretical calculations

The experimental and theoretical 1H and 13C chemical shifts, along with the error for each compound, are presented in Tables 2–7. A least-squares fit (theoretical calculation values/experimental calculation values) of all data shows a strong linear relationship with a R value of 0.999. This relationship is also reflected in the results for the individual compound, in which R values are 0.999, 0.976 (2a); 0.999 (2b); 0.999, 0.987 (2c); 0.999, 0.979 (2d); 0.999, 0.986 (2e); 0.999, 0.998 (2f). The overall standard error of estimate is 3.17 with the 6-311G basis set. The following correlations δcalc = aδexp+ b were obtained: 2a (13C), SE (standard error) = 3.27, a = 1.04, b = 1.58; 2a (1H), SE = 1.63, a = 0.60, b = 1.59; 2b (13C), SE = 2.94, a = 1.04, b = 1.65; 2c (13C), SE = 3.70, a = 1.03, b = 2.89; 2c (1H), SE = 1.25, a = 0.41, b = 3.83; 2d (13C), SE = 4.23, a = 1.04, b = 2.96; 2d (1H), SE = 1.40, a = 0.62, b = 1.99; 2e (13C), SE = 4.97, a = 1.04, b = 2.72; 2e (1H), SE = 1.28, a = 0.40, b = 3.78; 2f (13C), SE = 2.83, a = 1.18, b = −1.68; 2f (1H), SE = 0.49, a = −0.16, b = 9.20.

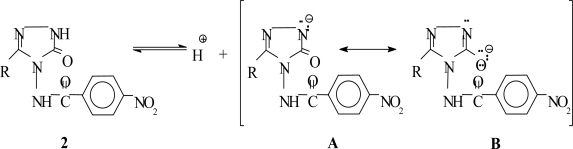

A linear correlation between theoretical and experimental carbon and proton chemical shifts was observed according to a, b and R values. A good quantitative agreement within 3.40–8.00 ppm in Tables 2–7 are observed for the aromatic carbons of these compounds. As can be seen at Tables 2–7, the errors range from 12.816 to 13.937 ppm for C-9 and C-14 for compound 2a due to attached nitrogen atoms. With the exception of the N-H protons, DFT method is in good agreement with the 1H spectrum of compounds 2a–f. There has occurred an important difference between experimental and theoretical results more than it is expected. The reason why such a result has come into being is that the N-H hydrogen in 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one ring has acidic properties, so that some 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives were titrated potentiometrically with TBAH in different non-aqueous solvents, and the pKa values were found between 8.69 and 16.75 [4,9–18]. Thus, in the 1H-NMR spectra of the 1,2,4-triazole and 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives, the signals of N-H protons were observed approximately δ 11 and 12 ppm [8–13,15–18,23,24,47,48]. This situation can be attributed to the resonance of the negatively formed ions (Scheme 2). Because of amide N-H proton, the errors range from 4.57 to 5.41 ppm for H-18 in compounds 2a, 2c–f were determined.

Scheme 2.

Conclusions

In this study, the structures of six new 3-alkyl(aryl)-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4- triazol-5-ones (2a–f) synthesized from the reactions of compounds 1a–f with p-nitrobenzoyl chloride were identified by using elemental analyses and IR, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and UV spectral data, and these obtained spectral values were seen as compatible with literature [2,4,7–14]. The newly synthesized compounds 2a–f were titrated potentiometrically with TBAH in four non-aqueous solvents such as acetone, isopropyl alcohol, tert-butyl alcohol and N,N-dimethylformamide of relative dielectric permittivity 20.6, 19.4, 12.0 and 36.7, respectively. From the titration curves, the HNP values and the corresponding pKa values were determined for all cases. These new compounds and five recently reported 3-alkyl-4-(2-furoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (3a–c,e,f) were also screened for their antioxidant activities. In addition, correlations between experimental chemical shifts and GIAO-calculated isotropic shielding constants of protons and carbons as obtained from six new 3- alkyl(aryl)-4-(p-nitrobenzoylamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones (2a–f) were established in order to assess the performance of NMR spectral calculations. DFT-B3LYP level of the theory 6-311G basis set was considered for geometry optimization and spectral calculations. Linear regressions, σcalc= a + bδexp, yield standard deviations of 1.40–4.18 ppm for hydrogen and carbon atoms.

Table 3.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2b.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 150,30 | 160,94 | −10,64 |

| C-2 | 153,80 | 158,17 | −4,37 |

| C-3 | 165,10 | 177,91 | −12,81 |

| C-4 | 136,85 | 144,87 | −8,02 |

| C-5 | 129,64 | 138,00 | −8,36 |

| C-6 | 124,15 | 130,47 | −6,32 |

| C-7 | 149,60 | 159,36 | −9,76 |

| C-8 | 124,15 | 130,34 | −6,19 |

| C-9 | 129,64 | 133,11 | −3,47 |

| C-10 | 18,22 | 24,45 | −6,23 |

| C-11 | 10,07 | 9,68 | 0,39 |

Table 4.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2c.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 150,05 | 159,38 | −9,33 |

| C-2 | 153,10 | 157,97 | −4,87 |

| C-3 | 164,73 | 177,25 | −12,52 |

| C-4 | 136,69 | 143,60 | −6,91 |

| C-5 | 129,59 | 138,49 | −8,90 |

| C-6 | 128,77 | 130,81 | −2,04 |

| C-7 | 147,19 | 159,28 | −12,09 |

| C-8 | 128,77 | 129,87 | −1,10 |

| C-9 | 129,59 | 130,45 | −0,86 |

| C-10 | 31,40 | 36,74 | −5,30 |

| C-11 | 135,03 | 140,48 | −5,45 |

| C-12 | 129,08 | 136,18 | −7,10 |

| C-13 | 124,00 | 134,79 | −10,79 |

| C-14 | 127,17 | 133,93 | −6,76 |

| C-15 | 124,06 | 134,86 | −10,80 |

| C-16 | 129,08 | 137,99 | −8,91 |

| H-17 | 12,01 | 6,88 | 5,13 |

| H-18 | 11,80 | 7,23 | 4,57 |

| H-19 | 8,14 | 8,44 | −0,30 |

| H-20 | 8,40 | 8,56 | −0,16 |

| H-21 | 8,40 | 8,48 | −0,08 |

| H-22 | 8,14 | 7,52 | 0,62 |

| H-23 | 3,89 | 3,93 | −0,04 |

| H-24 | 3,89 | 3,63 | 0,26 |

| H-25 | 7,29 | 7,13 | 0,16 |

| H-26 | 7,29 | 7,33 | −0,04 |

| H-27 | 7,29 | 7,30 | −0,01 |

| H-28 | 7,29 | 7,40 | −0,11 |

| H-29 | 7,29 | 7,42 | −0,13 |

Table 5.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2d.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 149,70 | 160,77 | −11,07 |

| C-2 | 152,75 | 158,19 | −5,44 |

| C-3 | 164,30 | 178,19 | −13,89 |

| C-4 | 136,20 | 144,91 | −8,71 |

| C-5 | 128,46 | 138,02 | −9,56 |

| C-6 | 129,10 | 130,60 | −1,50 |

| C-7 | 146,85 | 159,37 | −12,52 |

| C-8 | 129,10 | 130,27 | −1,17 |

| C-9 | 128,46 | 133,30 | −4,87 |

| C-10 | 30,40 | 36,57 | −6,17 |

| C-11 | 135,90 | 137,45 | −1,55 |

| C-12 | 128,84 | 136,15 | −7,31 |

| C-13 | 123,64 | 135,25 | −11,61 |

| C-14 | 131,60 | 145,33 | −13,73 |

| C-15 | 123,64 | 135,47 | −11,83 |

| C-16 | 128,84 | 137,99 | −9,15 |

| C-17 | 20,39 | 23,36 | −2,97 |

| H-17 | 11,94 | 6,86 | 5,08 |

| H-18 | 11,74 | 7,06 | 4,68 |

| H-19 | 8,14 | 8,23 | −0,09 |

| H-20 | 7,41 | 8,52 | −1,11 |

| H-21 | 8,41 | 8,54 | −0,13 |

| H-22 | 8,14 | 7,96 | 0,18 |

| H-23 | 3,80 | 4,23 | −0,43 |

| H-24 | 3,80 | 3,55 | 0,25 |

| H-25 | 7,13 | 7,01 | 0,12 |

| H-26 | 7,13 | 7,05 | 0,08 |

| H-27 | 7,13 | 7,30 | −0,17 |

| H-28 | 7,13 | 7,42 | −0,29 |

| H-29 | 2,27 | 2,02 | 0,25 |

| H-30 | 2,27 | 2,73 | −0,46 |

| H-31 | 2,27 | 2,42 | −0,15 |

Table 6.

Comparision between experimental and calculated chemical shifts (ppm) of 2e.

| Nuclei | Experimental | B3LYP/6-311G | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 150,20 | 160,03 | −9,83 |

| C-2 | 153,10 | 158,01 | −4,91 |

| C-3 | 164,80 | 178,36 | −13,56 |

| C-4 | 136,60 | 144,43 | −7,83 |

| C-5 | 129,64 | 138,03 | −8,39 |

| C-6 | 124,12 | 130,65 | −6,53 |

| C-7 | 146,80 | 159,52 | −12,72 |

| C-8 | 124,12 | 130,31 | −6,19 |

| C-9 | 129,64 | 133,24 | −3,60 |

| C-10 | 30,60 | 36,10 | −5,50 |

| C-11 | 132,10 | 139,97 | −7,87 |

| C-12 | 128,73 | 137,42 | −8,69 |

| C-13 | 131,01 | 134,39 | −3,38 |

| C-14 | 134,20 | 157,38 | −23,18 |

| C-15 | 131,01 | 134,71 | −3,70 |

| C-16 | 128,73 | 139,36 | −10,63 |

| H-17 | 12,19 | 6,88 | 5,31 |

| H-18 | 11,94 | 7,07 | 4,87 |

| H-19 | 8,31 | 8,23 | 0,08 |

| H-20 | 8,58 | 8,52 | 0,06 |

| H-21 | 8,58 | 8,54 | 0,04 |

| H-22 | 8,31 | 7,94 | 0,37 |

| H-23 | 4,07 | 4,27 | −0,20 |

| H-24 | 4,07 | 3,51 | 0,56 |

| H-25 | 7,45 | 7,03 | 0,42 |

| H-26 | 7,54 | 7,13 | 0,41 |

| H-27 | 7,54 | 7,23 | 0,31 |

| H-28 | 7,45 | 7,40 | 0,05 |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Asistants Özlem Gürsoy-Kol and Haci Baykara, Chemistry Department of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Kafkas University, for their help.

References

- 1.Ikizler AA, Uçar F, Yüksek H, Aytin A, Yasa I, Gezer T. Synthesis and antifungal activity of some new arylidenamino compounds. Acta Pol Pharm-Drug Res. 1997;54:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yüksek H, Demibaş A, Ikizler A, Johansson CB, Çelik C, Ikizler AA. Synthesis and antibacterial activities of some 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1997;47:405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirbaş N, Uğurluoğlu R. Synthesis and antitumor activities of some 4-(1- naphthylidenamino)- and 4-(1-naphthylmethylamino)-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives. Turk J Chem. 2004;28:679–690. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkan M, Yüksek H, İslamoğlu F, Bahçeci Ş, Calapoğlu M, Elmastaş M, Akşit H, Özdemir M. A study on 4-acylamino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Molecules. 2007;12:1805–1816. doi: 10.3390/12081805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yüksek H, Kolaylı S, Küçük M, Yüksek MO, Ocak U, Şahinbaş E, Sivrikaya E, Ocak M. Synthesis and andioxidant activities of some 4-benzylidenamino-4,5-dihydro-1H- 1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives. Indian J Chem. 2006;45B:715–718. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat AR, Bhat GV, Shenoy GG. Synthesis and in-vitro antimicrobial activity of new 1,2,4- triazoles. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001;53:267–272. doi: 10.1211/0022357011775307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikizler A, Doğan N, Ikizler AA. The acylation of 4-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5- ones. Rev Roum Chim. 1998;43:741–746. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikizler AA, Yüksek H. Acetylation of 4-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Org Prep Proced Int. 1993;25:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yüksek H, Alkan M, Ocak Z, Bahçeci Ş, Ocak M, Özdemir M. Synthesis and acidic properties of some new potential biologically active 4-acylamino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol- 5-one derivatives. Indian J Chem. 2004;43B:1527–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yüksek H, Ocak Z, Alkan M, Bahçeci Ş, Özdemir M. Synthesis and determination of pKa values of some new 3,4-disubstituted-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives in nonaqueous solvents. Molecules. 2004;9:232–240. doi: 10.3390/90400232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahçeci Ş, Yüksek H, Ocak Z, Azaklı A, Alkan M, Ozdemir M. Synthesis and potentiometric titrations of some new 4-(benzylideneamino)-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives in non-aqueous media. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 2002;67:1215–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahçeci Ş, Yüksek H, Ocak Z, KÖksal C, Ozdemir M. Synthesis and non-aqueous medium titrations of some new 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives. Acta Chim Slov. 2002;49:783–794. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikizler AA, Ikizler A, Şentürk HB, Serdar M. The pKa values of some 1,2,4-triazole and 1,2,4-triazolin-5-one derivatives in nonaqueous media. Doğa-Tr Kimya D. 1988;12:57–66. [Chem. Abstr. 1988, 109, 238277q] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikizler AA, Şentürk HB, Ikizler A. pK′a values of some 1,2,4-triazole derivatives in nonaqueous media. Doğa-Tr J of Chem. 1991;15:345–354. [Chem. Abstr. 1992, 116, 173458x] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yüksek H, Ocak Z, Özdemir M, Ocak M, Bekar M, Aksoy M. A study on novel 4- heteroarylidenamino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Indian J Heterocy Ch. 2003;13:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yüksek H, Bahçeci Ş, Ocak Z, Alkan M, Ermiş B, Mutlu T, Ocak M, Özdemir M. Synthesis of some 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Indian J Heterocy Ch. 2004;13:369–372. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yüksek H, Üçüncü O, Alkan M, Ocak Z, Bahçeci Ş, Özdemir M. Synthesis and nonaqueous medium titrations of some new 4-benzylidenamino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives. Molecules. 2005;10:961–970. doi: 10.3390/10080961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yüksek H, Bahçeci Ş, Ocak Z, Özdemir M, Ocak M, Ermiş B, Mutlu T. Synthesis and determination of acid dissociation constants of some new 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives. Asian J Chem. 2005;17:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schleyer PVR, Allinger NL, Clark T, Gasteiger J, Kolmann PA, Schaefer HF, Schreiner PR. The encyclopedia of computational chemistry. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ditchfield R. Self-consistent perturbation theory of diamagnetism. I A gauge-invariant LCAO method for N.M.R. chemical shifts. Mol Phys. 1974;27:789–807. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barfiled M, Fagerness PJ. Density Functional Theory/GIAO Studies of the 13C, 15N, and 1H NMR chemical shifts in aminopyrimidines and aminobenzenes: relationships to electron densities and amine group orientations. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;119:8699–8711. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manaj JM, Maciewska D, Waver I. 1H, 13C and 15N NMR and GIAO CPHF calculations on two quinoacridinium salts. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:482–485. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yüksek H, Gürsoy Ö, Çakmak İ, Alkan M. Synthesis and GIAO NMR calculation for some new 4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives: comparison of theoretical and experimental 1H and 13C chemical shifts. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43:585–587. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yüksek H, Çakmak İ, Sadi S, Alkan M. Synthesis and GIAO NMR calculations for some novel 4-heteroarylidenamino-4,5-dihydro-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-one derivatives: comparison of theoretical and experimental 1H and 13C chemical shifts. Int J Mol Sci. 2005;6:219–229. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussain HH, Babic G, Durst T, Wright J, Flueraru M, Chichirau A, Chepelev LL. Development of novel antioxidants: design, synthesis, and reactivity. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7023–7032. doi: 10.1021/jo0301090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClements J, Decker EA. Lipid oxidation in oil water emulsions: Impact of molecular environment on chemical reactions in heterogeneous food system. J Food Sci. 2000;65:1270–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikizler AA, Un R. Reactions of ester ethoxycarbonylhydrazones with some amine type compounds. Chim Acta Turc. 1979;7:269–290. [Chem. Abstr. 1991, 94, 15645d] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Japan Nutri. 1986;44:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;26:1199–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinis TCP, Madeira VMC, Almeida LM. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;315:161–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03, Revision C 02. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.London F. J Phys Radium. 1937;8:3974. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hameka HF. On the magnetic shielding in the hydrogen molecule. Mol Phys. 1958;1:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolinski K, Hilton KJF, Pulay P. Efficient implementation of the Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbital Method for NMR chemical shift calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8251–8260. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Womacott TM, Womacott RJ. Introductory Statistics. 5th Edition. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meir S, Kanner J, Akiri B, Hadas SP. Determination and involvement of aqueous reducing compounds in oxidative defense systems of various senescing leaves. J Agri Food Chem. 1995;43:1813–1819. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yildirim A, Mavi A, Kara AA. Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L. extracts. J Agri Food Chem. 2001:4083–4089. doi: 10.1021/jf0103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumann J, Wurn G, Bruchlausen V. Prostaglandin synthetase inhibiting O2- radical scavenging properties of some flavonoids and related phenolic compounds. Naunyn- Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1979;308:R27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soares JR, Dinis TCP, Cunha AP, Ameida LM. Antioxidant activities of some extracts of Thymus zygis. Free Raical Res. 1997;26:469–478. doi: 10.3109/10715769709084484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duh PD, Tu YY, Yen GC. Antioxidant activity of water extract of Harng Jyur (Chyrsanthemum morifolium Ramat) Lebn Wissen Techno. 1999;32:269. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi F, Ariga T, Yoshimira Y, Nakazawa H. Antioxidative and anti-glycation activity of garcinol from Garcinia indica fruit rind. J Agri Food Chem. 2000;48:180–185. doi: 10.1021/jf990845y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strlic M, Radovic T, Kolar J, Pihlar B. Anti- and prooxidative properties of gallic acid in fenton-type systems. J Agri Food Chem. 2002;50:6313–6317. doi: 10.1021/jf025636j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finefrock AE, Bush AI, Doraiswamy PM. Current status of metals as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1143–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Çaliş I, Hosny M, Khalifa T, Nishibe S. Secoiridoids from Fraxinus angustifolia. Phytochemistry. 1993;33:1453–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon MH. Food Antioxidants. Elsevier; London-New York: 1990. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hargis LG. Analytical Chemistry Principles and Techniques. Prentice-Hall Inc.; New Jersey: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikizler AA, İkizler A, Yüksek H. 1H-NMR spectra of some 4,5-dihydro-1,2,4-triazol-5-ones. Magn Reson Chem. 1993;31:1088–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ikizler AA, Yüksek H, Bahçeci Ş. 1H-NMR spectra of some ditriazolyls and ditriazolylalkanes. Monatsh Chem. 1992;123:191–198. [Google Scholar]