Abstract

Most gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) exhibit aberrant activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) KIT. The efficacy of the inhibitors imatinib mesylate and sunitinib malate in GIST patients has been linked to their inhibition of these mutant KIT proteins. However, patients on imatinib can acquire secondary KIT mutations that render the protein insensitive to the inhibitor. Sunitinib has shown efficacy against certain imatinib-resistant mutants, although a subset that resides in the activation loop, including D816H/V, remains resistant. Biochemical and structural studies were undertaken to determine the molecular basis of sunitinib resistance. Our results show that sunitinib targets the autoinhibited conformation of WT KIT and that the D816H mutant undergoes a shift in conformational equilibrium toward the active state. These findings provide a structural and enzymologic explanation for the resistance profile observed with the KIT inhibitors. Prospectively, they have implications for understanding oncogenic kinase mutants and for circumventing drug resistance.

Keywords: kinase inhibitor, signal transduction, targeted therapy, resistance mechanism, cancer

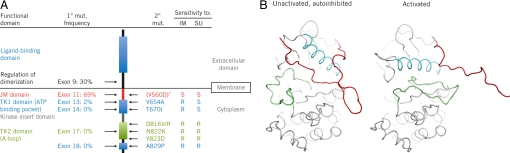

Acquired resistance to systemic therapy is a critical problem in treating metastatic cancers. Improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance should provide insights leading to development of alternative treatment strategies or design of new therapeutic entities that could be used to circumvent desensitization. One example of acquired resistance is the secondary mutants of KIT identified in GIST. Most GISTs have primary activating mutations in the genes encoding the closely related RTKs KIT (≈85% of GIST patients) or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA; ≈5% of patients) (1). The majority of KIT mutations affect the juxtamembrane (JM) region of the protein encoded by exon 11 of the gene, such as V560D (Fig. 1A). Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec™; an inhibitor of KIT and PDGFRs, as well as BCR-ABL) is currently first-line treatment for advanced GIST. Clinical response and duration of clinical benefit with imatinib correlate with KIT and PDGFRA genotype in GIST (2). Unfortunately, the majority of patients eventually show resistance to the drug: ≈14% of patients are initially insensitive to imatinib, and ≈50% of patients develop resistance within 2 years (3, 4). The latter resistance commonly occurs via secondary gene mutations in the KIT TK domains (Fig. 1A) (5). An effective second-line treatment is provided by sunitinib malate (Sutent™), which is approved multinationally for the treatment of advanced GIST after failure of imatinib due to resistance or intolerance. Sunitinib is an inhibitor of multiple RTKs, notably in this context, KIT and PDGFRA, and has been shown to be effective against certain imatinib-resistant KIT mutants, such as the ATP-binding-pocket mutants V654A and T670I. However, certain imatinib-resistant mutants are also resistant to sunitinib, including D816H/V (6), which are located in the activation loop (A-loop) of the KIT catalytic domain (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the KIT gene and protein. (A) Schematic representation of KIT showing location of functional domains, primary (1°) and secondary (2°) mutations (mut.). Frequencies of primary KIT genotypes, specific secondary KIT mutations, and resistance (R) or sensitivity (S) to imatinib (IM) or sunitinib (SU) were those reported in a phase I/II trial of sunitinib in advanced GIST after imatinib failure (6). V560D, substitution of Asp for Val at residue 560. (B) The unactivated, autoinhibited and activated forms of WT KIT (7, 8). The JM domain (red), A-loop (green), and C α-helix (cyan) are oriented differently in the autoinhibited and activated states. *V560D generally occurs as a primary mutation.

Previous structural studies (7, 8) had shown that KIT can sample diverse conformations (Fig. 1B): the unactivated, autoinhibited conformation [in which the Asp-810-Phe-811-Gly-812 (DFG) triad at the beginning of the A-loop is in the “DFG-out” orientation, with the DFG Phe oriented near the ATP-binding pocket, and the JM domain bound in the pocket vacated by DFG Phe], the unactivated DFG-out conformation with the JM domain oriented into the solvent, and the activated conformation (in which the canonical “DFG-in” conformation buries the Phe away from the ATP-binding pocket and the A-loop extends over the C terminus of the catalytic domain). The protein can be considered to be in equilibrium among these conformations, with a shift to the activated form upon phosphorylation.

The mechanism of KIT resistance to sunitinib could not be deduced in modeling studies using the published structures described above (7, 8). We therefore sought to investigate the mechanism using structural biological and functional enzymology studies of WT and mutated KIT proteins comprising the JM and kinase domains.

Results

Sunitinib and Imatinib Prevent KIT Activation by Targeting the Unactivated Conformation of KIT.

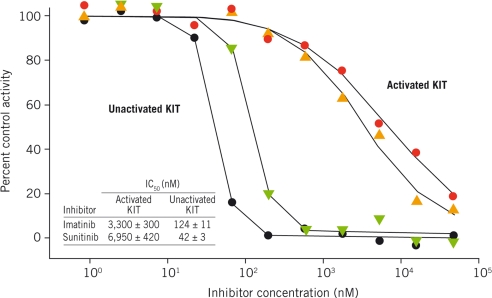

Sunitinib and imatinib are more potent inhibitors of unactivated WT KIT than fully activated, phosphorylated WT KIT (Fig. 2). This was determined initially in biochemical experiments with activated WT KIT. In enzyme assays containing 1.2 mM ATP and activated WT KIT, sunitinib and imatinib were only weakly active against the enzyme (IC50s: 7.0 and 3.3 μM, respectively). The unactivated enzyme state was then assayed: Unactivated WT KIT (40 nM) was incubated with sunitinib or imatinib and 4 mM ATP for 16 h, followed by measurement of kinase activity to quantify the amount of activated KIT produced. Both inhibitors were very effective at inhibiting autoactivation even at physiological ATP concentration (4 mM; Fig. 2) (IC50s: sunitinib, 42 nM; imatinib, 124 nM). Because imatinib has been shown to bind to KIT in the DFG-out, unactivated kinase conformation (8), it was expected to be more effective against unactivated KIT than activated enzyme. However, sunitinib has been reported to be an ATP-competitive inhibitor of various kinases, including VEGFR2 and PDGFRB (9), so the more potent inhibition of the unactivated relative to the activated form of KIT by sunitinib was surprising.

Fig. 2.

Sunitinib and imatinib inhibit unactivated KIT more effectively than activated KIT. Effects of sunitinib (red circles) and imatinib (gold triangles) on activated KIT were assayed in a mixture containing 1.2 mM ATP and 0.25 mg/mL poly(Glu-Tyr); the rate of ATP depletion was followed. Effects of sunitinib (black circles) and imatinib (green triangles) on KIT autoactivation were assayed in a mixture containing 40 nM unactivated KIT and 4 mM ATP for 16 h. Activated KIT resulting from this autoactivation reaction in the presence/absence of inhibitors was estimated based on kinase activity of the activated enzyme. IC50 values were determined as described in Methods.

Activated Mutant KIT Proteins Behave Similarly to Activated WT KIT.

Biochemical characterization of mutant activated KIT proteins was undertaken. Efforts to provide purified double-mutant proteins containing primary and secondary mutations observed in the clinic (V560D + D816H, V560D + D816V, and V560D + V654A) in sufficient quantity for structural experiments were unsuccessful. However, crystallography-quality D816H protein was made in sufficient amounts for structural studies. This mutant, along with the D816V and V654A single mutants, was studied biochemically, providing insight into the impact of point mutations. Additionally, the clinically relevant mutants V560D and V560D + T760I were characterized and assayed. Biochemical studies showed that once fully activated, all KIT mutants tested were virtually indistinguishable from WT (Table 1): Their catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) were all within 3-fold of WT KIT. Also, sunitinib was almost ineffective against activated mutants, similar to what was observed with WT KIT.

Table 1.

WT and mutant KIT: kinase activity of activated proteins and affinity of sunitinib for unactivated proteins

| Protein | Kinase activity of activated proteins |

Unactivated proteins |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP Km, μM | kcat, s−1 | kcat/Km, s−1M−1 | SU IC50, μM | SU Kd*, nM | |

| WT | 42.5 | 1.67 | 39,294 | 21 | 20 ± 13 |

| D816H | 22.0 | 1.29 | 58,636 | >30 | 22 ± 15 |

| D816V | 17.0 | 0.55 | 32,559 | >30 | 13 ± 6 |

| V560D | 35.0 | 1.47 | 41,857 | 25 | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| V654A | 13.5 | 1.26 | 93,333 | 8.6 | ND |

| V560D + T670I | 12.8 | 0.96 | 75,156 | >30 | 14 ± 9 |

cat, catalytic; SU, sunitinib; ND, not determined.

*Determined by using the Trp fluorescence quench assay.

Fluorescence Studies Show Sunitinib Binds to Unactivated WT and Mutant KIT.

Binding of sunitinib to unactivated WT KIT or mutants D816H, D816V, V560D, and V560D + T670I was measured by monitoring the quenching of intrinsic protein fluorescence that occurs upon inhibitor binding to KIT [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. As shown in Table 1, the dissociation constants (Kd) for sunitinib binding to unactivated WT KIT and mutant proteins were within 2-fold of each other, with the exception of mutant V560D, for which the Kd was ≈5-fold lower (Table 1). Thus, sunitinib binds to the unactivated forms of WT and mutant KIT proteins, which does not explain the loss in sunitinib sensitivity observed for A-loop mutants in the clinical setting.

Structural Data Reveal Sunitinib Binds to Autoinhibited KIT.

Structural studies were undertaken to determine the mode of sunitinib binding to the unactivated KIT protein. The sunitinib-bound crystal structure of KIT revealed that the protein is in an unactivated, autoinhibited conformation (Fig. 3A, Table S1). The root mean-square deviation between αC atoms of the previously determined autoinhibited apo protein structure (8) and the sunitinib-bound form presented here was 0.9 Å. The only noteworthy difference between the 2 structures was restricted to the DFG triad at the beginning of the A-loop. In both, the DFG triad was oriented such that the side chain of Phe-811 faced the ATP-binding pocket of the enzyme. However, in the sunitinib-bound form, Phe-811 had to reorient for sunitinib to occupy the ATP-binding pocket, requiring the DFG triad to reposition slightly (Fig. 3B). Sunitinib bound in the ATP-binding pocket between the N and C lobes of the kinase domain such that the dihydrooxaindole ring accessed the deep end of the pocket, partially overlapping with the space occupied by the bound ADP adenine ring in the phosphorylated protein (7), whereas the aliphatic diethylaminoethyl tail was exposed to the solvent and disordered (Fig. S2A). Molecular recognition was through both specific polar interactions and nonspecific van der Waals contacts (Fig. 3B). The NH and O atoms of the sunitinib dihydrooxaindole ring system make up the donor–acceptor motif that is frequently part of kinase inhibitors and participates in hydrogen-bonding interactions with the backbone amides in the interlobe hinge region of the protein.

Fig. 3.

Sunitinib recognizes the autoinhibited form of KIT. WT KIT bound to sunitinib is shown in yellow (JM domain, red; A-loop, green; C α-helix, cyan). (A) WT KIT bound to sunitinib is very similar to the published autoinhibited structure of KIT (gray) (7, 8). Amino acid side chains are shown at the sites of A-loop substitutions found in sunitinib-resistant GISTs. (B) Sunitinib-binding site in the complex and apo structures. Drug binding induces a slight rearrangement of the Phe-811 side chain relative to the apo form. (C) The overall structure of the D816H mutant bound to sunitinib (darker blue) is very similar to that with WT, except for the proposed dislocation of the JM domain from its autoinhibitory position. Residue 816 is shown for both proteins.

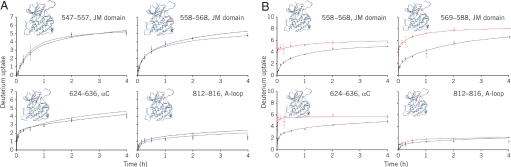

KIT contains a kinase insertion domain (KID) as do other split TKs. All KIT WT and mutant proteins investigated in the biochemical studies described contained the KID. However, because of an inability to crystallize KIT proteins with the KID intact, crystallographic experiments were performed by using constructs in which the KID was deleted. Direct evidence of this domain's influence on the conformation of the whole kinase would therefore be insightful. Solution-phase hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) experiments with high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis for 2 constructs of KIT (the WT KIT kinase domain with and without the KID) were performed under the same conditions. HDX rates of all of the covered peptides were similar in both proteins in the absence or presence of sunitinib (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3). This result verified that the KID has no major influence on KIT conformation or on sunitinib inhibition of KIT. Likewise, unactivated KIT with or without the KID showed similar affinity for sunitinib in protein fluorescence-quench experiments (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

HDX analysis of WT and mutant KIT. (A) HDX time courses for WT KIT with (blue) or without the KID (black) showed no significant conformational differences in the JM domain (residues 542–586), the αC segment (residues 624–636), or the A-loop (residues 810–834). (B) HDX time courses for the D816H mutant (red) and WT KIT (blue). Most of the D816H mutant peptides were more solvent exposed than those of WT KIT, implying that the mutant protein is more flexible than the WT protein.

Sunitinib Inhibits Autophosphorylation of Unactivated KIT Mutants.

Although sunitinib was virtually ineffective against activated WT and mutant KIT at physiological ATP concentrations, the drug effectively inhibited almost all of the unactivated enzymes in an autoactivation reaction run for 1 h (Table 2). However, inhibition of mutant KIT quickly diminished after 4 h in the assay. These results show that the drug-resistant mutants maintain their ability to bind sunitinib in an unactivated conformation, consistent with the binding results described above. As the unactivated kinase is converted to the active form, the conformation of the active site becomes less favorable for sunitinib binding, due at least in part to competition with ATP, resulting in reduced drug potency.

Table 2.

WT and mutant KIT: inhibition by sunitinib and rates of auto-activation

| Protein | Sunitinib IC50 (μM) |

Activation rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unactivated KIT |

Activated KIT |

|||||

| 1 h | 4 h | 16 h | 1 h | mM−1s−1 | × WT | |

| WT | Low signal | 0.04 | 0.04 | 21.00 | 0.25 | 1 |

| D816H | 0.21 | 3.20 | >10.00 | >30.00 | 46 | 184 |

| D816V | 7.10 | >10.00 | >10.00 | >30.00 | 134 | 536 |

| V560D | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 25.00 | >150 | >600 |

| V654A | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 8.60 | 4.8 | 19 |

| V560D + T670I | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.36 | >30.00 | >150 | >600 |

| ΔJM | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.53 | >30.00 | ND | ND |

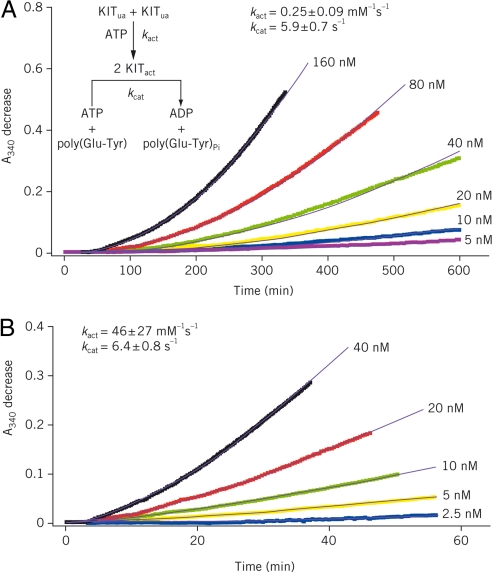

KIT A-Loop Mutants Autoactivate Much Faster Than WT KIT.

Time courses of WT KIT autoactivation at varying enzyme concentrations are shown in Fig. 5A. For a bimolecular autoactivation reaction coupled with a kinase activity assay run at saturating substrate concentration, rate equations for active KIT production and the subsequent formation of KIT-catalyzed kinase reaction product (ADP) afford determination of the activation and catalytic rate constants, kact and kcat, respectively. Fitting the data in Fig. 5A to Eq. 1 in Methods gave a kact of 0.25 ± 0.09 mM−1s−1 for WT KIT activation and a kcat of 5.9 ± 0.7 s−1 for the subsequent KIT-catalyzed kinase reaction.

Fig. 5.

KIT A-loop mutant D816H autoactivates at a much faster rate than WT enzyme. WT KIT (A) and D816H mutant (B) autoactivation was conducted in a reaction mixture containing 4 mM ATP and various starting concentrations of unactivated (ua) KIT as indicated. Autoactivation was monitored in a real-time manner by coupling the activation product [activated (act) KIT] to the kinase activity assay reaction described in Methods by using a saturating poly(Glu-Tyr) concentration (1.5 mg/ml). ADP production resulting from the reaction catalyzed by active KIT was followed by measuring absorbances at 340 nm (A340; colored traces) in the ATP-regeneration system described in Methods. Fitting the data to Eq. 1 in Methods gave the simulated results shown as solid black curves and second-order rate constants (kact) of 0.25 ± 0.09 and 46 ± 27 mM−1s−1 for WT KIT and D816H mutant, respectively.

Similar experiments were performed with each KIT mutant. A representative example (D816H) is shown in Fig. 5B. Autoactivation rate constants for each mutant are provided in Table 2. Autoactivation rates of KIT A-loop mutants D816H and D816V were substantially faster than that of WT KIT (184- and 536-fold, respectively). The increase in the activation rate of these mutants compared with WT KIT correlated well with loss of sunitinib potency during the course of autoactivation shown in Table 2. Conversely, the “gatekeeper” mutation T670I did not alter the autoactivation rate and showed no effect on sunitinib binding (compare V560D + T670I and V560D). Together, these results suggest that the accelerated autoactivation of D816H and D816V mutants might play a significant role in their resistance to sunitinib. Interestingly, although mutants harboring the V560D mutation exhibited the greatest increase in activation rates (Table 2; Fig. S4), they remained more sensitive to sunitinib through the study time course than the A-loop mutants D816H/V. This phenomenon may be related to the different conformations populated by the various mutants.

KIT D816H Impacts the Autoinhibitory Conformation of the JM Domain.

To complement the structural studies of sunitinib bound to KIT, we sought to determine the structure of the D186H KIT–sunitinib complex. Despite extensive crystallization experimentation, D816H KIT could not be crystallized. This was reminiscent of the experience reported for KIT–imatinib (8), where limited proteolysis of the complex yielded diffraction-quality crystals. To explore further, limited proteolysis experiments with D816H KIT and different proteases were performed. Glu-C was found to cleave part of the JM domain in the presence of sunitinib; therefore, crystallization experiments were carried out in the presence of this enzyme, yielding diffraction-quality crystals in complex with sunitinib (Fig. 3C). The resulting 2.6-Å-resolution electron density map, as well as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry experiments on the crystals, indicated that Glu-C cleaves KIT at the C terminus of Glu-562, truncating the N-terminal region by 19 residues. D816H KIT displayed the protease cleavage site in the same region as reported for the WT imatinib-bound protein. The D816H variant was also significantly more susceptible to Glu-C proteolysis than was the WT protein, indicative of JM exposure to solvent. Imatinib binding kinetics further support this inference. Imatinib, unlike sunitinib, is occluded by the autoinhibitory conformation of the JM domain, which is a likely cause of imatinib being a slow binder of KIT. Therefore, destabilization of the autoinhibitory conformation should result in faster imatinib binding. Indeed, the on-rate of imatinib binding to the D816H mutant was 4.3-fold higher than to WT (see Methods), consistent with less steric hindrance by the JM domain for binding. In HDX experiments, the HDX rate of the D816H JM domain exceeded the already high exchange rate of the WT JM domain (Fig. 4B). The HDX rate for the N lobe residues adjacent to the JM domain increased significantly, indicating less protection from the JM segment. We therefore propose that the D816H substitution negatively influences the inhibitory conformation of the JM domain such that the equilibrium is shifted from the autoinhibited state of the kinase to one with a solvated, disordered JM domain.

Sunitinib Interacts Similarly with the D816H Mutant and WT KIT.

An analysis of the D816H mutant complex revealed that the interaction of sunitinib with the mutant protein was very similar to that seen with WT (Fig. 3C). The mutant and WT ATP-binding pockets, to which sunitinib bound, were virtually identical except near the DFG triad. The peptide bond connecting Gly-812 to Leu-813 was flipped by 180° in the D816H KIT relative to the WT kinase. However, this did not seem to be the direct result of the specific substitution D816H. The A-loop conformation after the DFG triad in the mutant protein was very similar to that in the WT.

Sunitinib Binds to the Unactivated Imatinib-Resistant KIT T670I Protein.

Mutations of the gatekeeper residue in TKs are frequently associated with drug resistance (10–12). The gatekeeper KIT mutant (T670I) observed in patients with GIST corresponds to that found in Bcr-Abl that confers resistance to imatinib in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients (10, 13, 14). Similarly, the gatekeeper KIT mutant T670I is insensitive to imatinib (15). In our studies, imatinib was a weak inhibitor (IC50 = 1 μM) of the V560D + T670I double-mutant protein. This substitution with the larger Ile clearly impedes imatinib binding. Because sunitinib does not access the deep hydrophobic pocket as does imatinib, there is enough space to accommodate the additional C atom associated with the T670I mutation without affecting sunitinib binding (Fig. S2B). This is consistent with the observation shown in Table 2 that the double mutation V560D + T670I exhibits little effect on the autoactivation rate and sensitivity to sunitinib.

Discussion

In 2006, sunitinib received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of patients with imatinib-resistant GIST. The underlying mechanism of action for both drugs in the majority of patients is believed to be inhibition of oncogenic KIT mutants. Imatinib has been shown to target the unactivated state of the enzyme. On the other hand, sunitinib has frequently been assumed to bind to the ATP-binding pocket of kinases and to inhibit the active form of the enzyme in an ATP-competitive manner. Our studies show that sunitinib binds to the unactivated conformation of KIT at the ATP-binding pocket, thus blocking autoactivation. Sunitinib is only weakly effective in inhibiting the active form of KIT in the presence of physiologically relevant ATP concentrations. The finding that sunitinib binds to the autoinhibited form of KIT highlights the importance of targeting various conformations of protein kinases and is a result with great potential impact on kinase research.

Because of the inability to crystallize KIT with the KID intact, solution-phase HDX experiments were used to verify that the KID had no conformational effect on KIT either in the presence or absence of sunitinib. The inferences from the crystal structures of KIT without the KID are therefore expected to be relevant to the full-length cytoplasmic protein. To elucidate the binding of the drug to the kinase, we determined the crystal structure of WT KIT with sunitinib. The complex revealed that the drug binds to the autoinhibited form of the enzyme, with the protein retaining a conformation very similar to that previously reported for the apo enzyme (8). Although imatinib also targets an unactivated kinase conformation, this inhibitor competitively displaces the JM domain from its inhibitory position.

The biochemical data indicate that sunitinib binds to the unactivated form of the mutant proteins as well as WT. Kinase activity assays using the active forms of KIT mutants D816H/V and V560D + T670I revealed that both sunitinib and imatinib are ineffective against this state of the mutant proteins in the presence of physiological ATP concentrations, as was observed with WT KIT. Measurement of autoactivation rates showed that the D816H and D816V mutants activate much faster than WT. Taken together, these data suggest that the drug resistance exhibited by D816H and D816V proteins is the result of a shift in equilibrium toward the active kinase conformation and an accelerated autophosphorylation of these mutants. The drug-resistant variants indeed bind sunitinib and imatinib in an unactivated conformation; however it is the conversion from the drug-favorable unactivated kinase conformation to the drug-insensitive active form in the presence of physiological ATP concentrations that results in loss of inhibition. Modeling of sunitinib binding into the activated kinase structure suggests that steric conflicts between the flexible glycine-rich loop and sunitinib could be one of the reasons for reduced drug sensitivity of the activated state (Fig. S2C).

The crystal structure of sunitinib bound to the KIT D816H mutant provides insight regarding the regulatory impact of the A-loop mutations. Unlike the crystallization experiments with WT KIT construct containing catalytic and JM domains, the corresponding D816H KIT variant did not crystallize. The inability to grow crystals with the D816H mutant may have been due to a disordered JM domain, similar to imatinib-bound KIT (8). The analogous proteolytic digestion was carried out with the D816H variant and resulted in truncated protein that cocrystallized with sunitinib, suggesting that the JM domain in the D816H KIT–sunitinib complex is indeed unstructured. Solution-phase HDX further verified that the JM domain in D816H is much more flexible or unstructured compared with WT KIT. Other results described above comparing the D816H mutant with WT KIT provided additional evidence supporting the solvated state of the JM domain in the mutated enzyme. Based on these observations, we propose that the D816H substitution negatively impacts the inhibitory conformation of the JM domain such that the equilibrium is shifted away from the autoinhibited state to the JM domain being released to solvent and disordered.

GISTs containing the gatekeeper mutation T670I that confers resistance to imatinib are highly sensitive to sunitinib. Biochemical and structural data presented in this report provide an explanation for the different drug sensitivities of GISTs to sunitinib and imatinib observed in patients.

The primary JM KIT mutation in GIST patients has been proposed to negatively impact the inhibitory conformation of the JM domain (16), an effect also observed for the A-loop mutant D816H in our studies. Because sunitinib and imatinib efficacies depend on targeting unactivated KIT, we propose that KIT A-loop mutations alter the conformational equilibrium of the kinase toward the active form. In the presence of ATP, this conformational impact leads to accelerated phosphorylation and production of the activated protein. D816H/V mutant proteins offer a smaller population of the molecular target to both sunitinib and imatinib, which manifests as abrogated efficacy of each drug in GIST patients in the clinical setting.

These studies suggest that successful cancer treatment regimens may require a mixture of kinase inhibitors that block various conformations of the target protein. Additionally, this strategy could potentially circumvent, or at least delay, the onset of drug resistance.

Methods

Cloning and Protein Purification.

KIT constructs were made as previously described (7) (details provided in SI Methods).

Kinase Activity Assay.

Activated KIT was prepared by incubating 10 μM unactivated KIT with 4 mM ATP. KIT kinase activity was determined by using a coupled assay method in an ATP-regenerating system as described previously (17) with slight modification. The steady-state rate of poly(Glu-Tyr) phosphorylation was computed from the observed linear decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (A340). To quantify inhibition of activated KIT by sunitinib and imatinib, 10 μL of activated KIT (400 nM) were incubated with 10 μL of sunitinib or imatinib (0–90 μM; 20 °C, 30 min), followed by addition of 80 μL of coupled assay mixture. A340 was followed to determine the KIT kinase activity (additional details in SI Methods).

Inhibition of KIT Autoactivation.

For a typical reaction, 40 nM unactivated KIT was preincubated with 0–90 μM sunitinib or imatinib (20 °C, 30 min), followed by addition of 4 mM ATP to initiate KIT autophosphorylation. Autophosphorylation/activation was allowed to continue for 1, 4, or 16 h at 20 °C. Autoactivation was monitored by determining the resultant KIT activity by adding 70 μL of ATP-regenerating coupled assay mixture; A340 was followed for 1 h. Eleven-point dose–response curves with inhibitor concentrations ranging from 0.3 nM to 30 μM were used to determine IC50s.

Binding Assay.

Direct sunitinib binding to mutant and WT KIT was detected by measuring intrinsic Trp fluorescence quenching that occurs upon drug binding to KIT. KIT (200 nM) was excited at 290 nm; the emission spectrum was collected at 300–450 nm. KIT protein spectra were collected after addition of small aliquots of sunitinib in 100% DMSO. To determine the Kd, fluorescence at 340 nm was plotted versus drug concentration and fit to the Morrison equation (18).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

WT protein in complex with sunitinib was crystallized at 13 °C in 10% PEG 6000, 0.1 M bicine (pH 9). D816H protein (8.4 mg/mL) was incubated with sunitinib overnight at 4 °C. Glu-C protease was added; the complex was incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Proteolysis was quenched with leupeptin. The protein complex was crystallized at 13 °C in 1.5 M ammonium sulfate. See SI Methods for additional details.

Autoactivation-Rate Determination.

For a bimolecular autoactivation reaction coupled with a kinase activity assay run at saturating substrate concentration, rate equations for active KIT production and the subsequent formation of KIT-catalyzed kinase reaction product (ADP) may be written as follows:

|

where [KITact] and [KITua] are activated and unactivated KIT concentrations, respectively. kact is the rate constant for KIT activation; kcat is the catalytic rate constant for activated KIT. Integration of these 2 rate equations gives:

|

Fitting the data in Fig. 5A to Eq. 2 gives activation rate constants kact and catalytic rate constants kcat.

On-Rate Determination for Unactivated KIT Binding to Imatinib.

Unactivated WT and D816H KIT samples were diluted to 200 nM in kinase activity assay buffer. Fifty-microliter samples were mixed with 50 μL of imatinib to give final imatinib concentrations of 60, 30, 15, and 7.5 μM, and 100 nM final [KIT]ua. The decrease in protein fluorescence intensity was measured with an excitation wavelength of 293 nm and an emission wavelength of 340 nm. For imatinib binding to WT and D816H KIT, binding progress curves were fitted to a single exponential function:

where Fo is the initial fluorescence of free KIT, and Foo is the imatinib-bound protein fluorescence intensity after equilibrium is established. Fobs is the observed fluorescence intensity at time t. The observed binding rate kobs was determined accordingly. The ratio kobs(D816H)/kobs(WT) at each imatinib concentration was calculated, giving an average ratio of 4.3 ± 1.3.

HDX Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) Mass Spectrometry.

HDX methods have been described previously (19, 20). Briefly, 5 μL of KIT (20 μM) were mixed with 45 μL of 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM TCEP in D2O to initiate each HDX period. Sunitinib (63 μM) was allowed to bind to 20 μM KIT for 1 h before HDX experiments. HDX was quenched by 1:1 (vol/vol) addition of protease type XIII solution in 1.0% formic acid. Microelectrosprayed (21) HDX samples were directed to a custom-built hybrid linear trap quadrupole 14.5-Tesla FT-ICR mass spectrometer (22). Data were analyzed by using an in-house analysis package. Time-courses of deuterium incorporation were generated after fitting the HDX data by using a maximum-entropy method (23).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported in part by funding from Pfizer Inc., the Ludwig Trust for Cancer Research, National Science Foundation Grant DMR-06-54118, Florida State University, and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Tallahassee, FL. Editorial assistance was provided by ACUMED (Tytherington, U.K.) and funded by Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: K.S.G., J.C.W., J.C., G. D. Deshmukh, W.D., J.P.D., J.M.E., M.J.G., Y-A.H., S.L.J., E.A.L., M.M., D.M., T.Q., P.A.W., X.Y., Y.Z., and A.Z. are Pfizer employees and stockholders or were at the time this work was carried out. M.R.E. holds Pfizer stock. G. D. Demetri has received consulting stipends and honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, Bayer, and Infinity, and his institution has received research funding from Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Infinity, and Exelixis.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0812413106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Heinrich MC. Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3813–3825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinrich MC, et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–4349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verweij J, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: Randomized trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonescu CR, et al. Acquired resistance to imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor occurs through secondary gene mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4182–4190. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinrich MC, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5352–5359. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mol CD, et al. Structure of a KIT product complex reveals the basis for kinase transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31461–31464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mol CD, et al. Structural basis for the autoinhibition and STI-571 inhibition of KIT tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31655–31663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendel DB, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: Determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorre ME, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293:876–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yun CH, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godin-Heymann N, et al. The T790M “gatekeeper” mutation in EGFR mediates resistance to low concentrations of an irreversible EGFR inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:874–879. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schindler T, et al. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289:1938–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou T, et al. Crystal structure of the T315I mutant of AbI kinase. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;70:171–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinrich MC, et al. Molecular correlates of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4764–4774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarn C, et al. Analysis of KIT mutations in sporadic and familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Therapeutic implications through protein modeling. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3668–3677. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu JC, Chuan H, Wang JH. A potent fluorescent ATP-like inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7989–7993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison JF. Kinetics of the reversible inhibition of enzyme-catalysed reactions by tight-binding inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;185:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H-M, et al. Enhanced digestion efficiency, peptide ionization efficiency, and sequence resolution for protein hydrogen/deuterium exchange monitored by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9034–9041. doi: 10.1021/ac801417d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H-M, et al. Fast reversed-phase liquid chromatography to reduce back exchange and increase throughput in H/D exchange monitored by FT-ICR mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emmett MR, Caprioli RM. Micro-electrospray mass spectrometry: Ultra-high-sensitivity analysis of peptides and proteins. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:605–613. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaub TM, et al. High-performance mass spectrometry: Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance at 14.5 Tesla. Anal Chem. 2008;80:3985–3990. doi: 10.1021/ac800386h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Li W, Logan TM, Li M, Marshall AG. Human recombinant [C22A] FK506-binding protein amide hydrogen exchange rates from mass spectrometry match and extend those from NMR. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2203–2217. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.