Abstract

Pegaptanib sodium (MacugenTM) is a selective RNA aptamer that inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 165 , the VEGF isoform primarily responsible for pathologic ocular neovascularization and vascular permeability, while sparing the physiological isoform VEGF 121 . After more than 10 years in development and preclinical study, pegaptanib was shown in clinical trials to be effective in treating choroidal neovascularization associated with age-related macular degeneration. Its excellent ocular and systemic safety profile has also been confirmed in patients receiving up to three years of therapy. Early, well-controlled studies further suggest that pegaptanib may provide therapeutic benefit for patients with diabetic macular edema, proliferative diabetic retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion. Notably, pegaptanib was the first available aptamer approved for therapeutic use in humans and the first VEGF inhibitor available for the treatment of ocular vascular diseases.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, aptamer, diabetic macular edema, pegaptanib, vascular endothelial growth factor

Studies of the pathophysiology of neovascular diseases of the eye, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy (DR), have demonstrated a central role for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; also known as VEGF-A) in the pathogenesis of these disorders. VEGF acts as a master regulator and promoter of angiogenesis1 and is also the most potent known promoter of vascular permeability.2 Ocular VEGF concentrations were found to be elevated in the eyes of patients suffering from neovascularizing conditions and preclinical studies showed that VEGF was both necessary and sufficient for the development of ocular neovascularization.3

These studies provided compelling evidence for the use of VEGF inhibitors in treating AMD patients. To date, two VEGF-targeting therapies have received regulatory approval for the treatment of neovascular AMD - pegaptanib sodium (Macugen TM ; OSI-Eyetech, Inc. and Pfizer, Inc.) approved in December 2004 and ranibizumab (Lucentis TM ; Genentech, Inc.) approved in June 2006. Pegaptanib is an RNA aptamer that inhibits the VEGF 165 isoform while sparing VEGF 121 . In contrast, ranibizumab is a Fab antibody fragment that binds to and inhibits all VEGF isoforms.4 This review focuses entirely on pegaptanib (for more detailed reviews see Ng et al .3 ; Cunningham et al.5 ).

Development of Pegaptanib

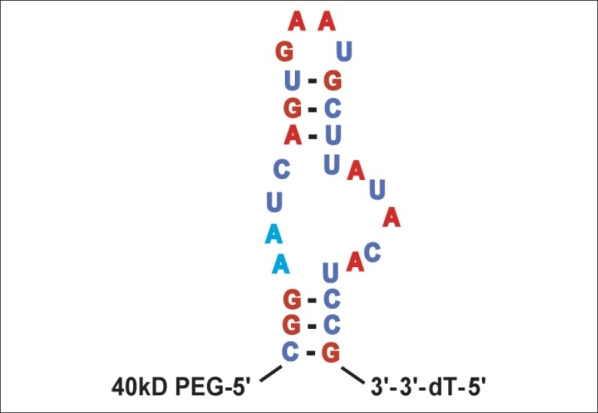

Pegaptanib was developed in the 1990s using the SELEX (selective evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) technique. The result was a 29-nucleotide aptamer, with a chemically modified RNA backbone that increases nuclease resistance and a 5′ terminus that includes a 40kD polyethylene glycol moiety for prolonged tissue residence [Fig. 1].3 Pegaptanib was shown to bind VEGF 165 with high specificity (kD = 200 pM) and inhibited VEGF 165 -induced responses, including cell proliferation in vitro and vascular permeability in vivo , while not affecting responses to VEGF 121 . Pegaptanib proved to be stable in human plasma for more than 18h, while in monkeys pegaptanib administered into the vitreous was detectable in the vitreous for four weeks after a single dose.3

Figure 1.

Sequence and predicted secondary structure of pegaptanib 3

Preclinical Findings

In rodent models,VEGF 164 (the rodent equivalent of human VEGF 165 ) acts as a potent inflammatory cytokine, mediating both ischemia-induced neovascularization and diabetes-induced breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB). In these experiments, intravitreous pegaptanib was shown to significantly reduce pathological neovascularization, while leaving physiological vascularization unimpaired6 and was also able to reverse diabetes-induced BRB breakdown.7 Moreover, VEGF 165 proved to be dispensable for mediating VEGF′s role in protecting retinal neurons from ischemia-induced apoptosis.8 These data suggested that intravitreous pegaptanib could provide a safe and effective treatment against both ocular neovascularization and diabetes-induced retinal vascular damage.

Clinical Studies

Neovascular AMD

Pivotal clinical trial data have demonstrated that pegaptanib is both effective and safe for the treatment of neovascular AMD. These data were derived from two randomized, double-masked studies known jointly as the V.I.S.I.O.N. (VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization) trials.9,10 A total of 1186 subjects with any angiographic subtypes of neovascular AMD were included. Patients received intravitreous injections of 0.3 mg, 1 mg or 3 mg pegaptanib or sham injections every six weeks for 48 weeks. Subjects with predominantly classic lesions could also have received photodynamic therapy with verteporfin (PDT; Visudyne TM , Novartis) at investigator discretion. After one year, the 0.3 mg dose conferred a significant clinical benefit compared to sham treatment as measured by proportions of patients losing < 15 letters of visual acuity (VA); compared with 55% (164/296) of patients receiving sham injections, 70% (206/294) of patients receiving 0.3 mg of pegaptanib met this primary endpoint ( P < 0.001). In contrast to PDT, clinical benefit was seen irrespective of angiographic AMD subtype, baseline vision or lesion size and led to the clinical approval of pegaptanib for the treatment of all angiographic subtypes of neovascular AMD. The 1 mg and 3 mg doses showed no additional benefit beyond the 0.3 mg dose.9 Treatment with 0.3 mg pegaptanib was also efficacious as determined by mean VA change, proportions of patients gaining vision and likelihood of severe vision loss. In an extension of the V.I.S.I.O.N. study, patients in the pegaptanib arms were rerandomized to continue or discontinue therapy for 48 more weeks.10 Compared to patients discontinuing pegaptanib or receiving usual care, those remaining on 0.3 mg pegaptanib received additional significant clinical benefit in the second year. Further subgroup analyses suggested that pegaptanib treatment was especially effective in those patients who were treated early in the course of their disease.11

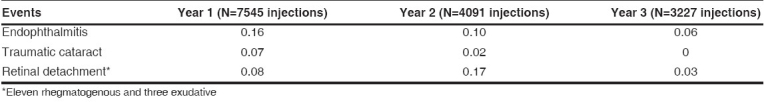

Pegaptanib showed an excellent safety profile. All dosages were safe, with most adverse events attributable to the injection procedure rather than to the study drug itself. In the first year, serious adverse events occurred with < 1% of intravitreous injections9 and no new safety signals have been identified in patients receiving pegaptanib for two and three years.12,13 The frequencies of serious ocular adverse events for all three years are presented in Table 1.12,13 In addition, no systemic safety signals have emerged over this period. These conclusions have also been confirmed in assessments of systemic parameters following intravitreous injection of 1 mg and 3 mg pegaptanib.14

Table 1.

Serious ocular adverse events, rates (% per injection)

Diabetic macular edema (DME)

Safety and efficacy of pegaptanib were assessed in a randomized, sham-controlled, double-masked, Phase 2 trial enrolling 172 diabetic subjects with DME affecting the center of the fovea. Intravitreous injections were administered at baseline and every six weeks thereafter. At Week 36, 0.3 mg pegaptanib was significantly superior to sham injection, as measured by mean change in VA (+4.7 letters vs. -0.4 letters, P =0.04), proportions of patients gaining ≥10 letters of VA (34% vs.10%; P =0.003), change in mean central retinal thickness (68µm decrease vs. 4 µm increase; P =0.02) and proportions of patients requiring subsequent photocoagulation treatment (25% vs. 48%, P =0.04).15 In addition, a retrospective subgroup analysis revealed that pegaptanib treatment led to the regression of baseline retinal neovascularization in eight of 13 patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) whereas no such regression occurred in three sham-treated eyes or in four untreated fellow eyes.16 Early results from a small, randomized, open-label study suggest that adding pegaptanib to panretinal photocoagulation conferred significant clinical benefit in patients with PDR.17

Macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO)

VEGF has been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRVO.18 Accordingly, in a trial that enrolled subjects with CRVO of < 6 months duration,19 98 subjects were randomized (1:1:1) to receive intravitreous pegaptanib (0.3 mg or 1 mg) or sham injections every six weeks and panretinal photocoagulation if needed. At Week 30, treatment with 0.3 mg pegaptanib was superior in terms of mean change in VA, proportions of patients losing ≥15 letters from baseline, proportions with a final VA of ≥35 letters and reduction in center point and central subfield thickness.19,20

Investigational studies with pegaptanib

Encouraging findings have been reported in small case series investigating the use of pegaptanib for the treatment of neovascular glaucoma,21 retinopathy of prematurity22 and familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.23 In addition, given its positive safety profile, now validated over three years in clinical trials and two and a half years of postmarketing experience, pegaptanib is being studied as a maintenance anti-VEGF inhibitor following induction with nonselective anti-VEGF agents such as ranibizumab or bevacizumab, which bind all VEGF isoforms24,25 and appear to be associated with an increased, albeit small, risk of stroke.26

Conclusions

Pegaptanib is both safe and clinically effective for the treatment of all angiographic subtypes of neovascular AMD. Early, well-controlled trials further suggest that pegaptanib may provide therapeutic benefit for patients with DME, PDR and RVO. The roles that pegaptanib will ultimately play as part of the ophthalmologist′s armamentarium remain to be established. The recent results with ranibizumab demonstrating the potential for significant vision gains in AMD27,28 have been impressive, but issues of safety remain to be definitively resolved;26 combinatorial regimens may ultimately prove to be most effective in balancing safety with efficacy.24 Similarly, more established approaches, such as photodynamic therapy with verteporfin, may provide greater clinical benefit when combined with anti-VEGF therapy,29 so that there is likely to be considerable space for empiricism in determining the best approach for a given patient. Nonetheless, the overall trend is highly positive, with the anti-VEGF agents affording many more options than were available only a few years ago. Such successes highlight the importance of VEGF in the pathogenesis of ocular vascular disorders and support the use of anti-VEGF agents as foundation therapy in patients with these conditions.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support, including contributing to the first draft of the manuscript, revising the paper based on author feedback and styling the paper for journal submission, was provided by Dr. Lauren Swenarchuk of Zola Associates and funded by Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Pfizer Inc.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senger DR, Connolly DT, Van de Water L, Feder J, Dvorak HF. Purification and NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of guinea pig tumor-secreted vascular permeability factor. Cancer Res. 1990;50:1774–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng EW, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET, Jr, Guyer DR, Adamis AP. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–32. doi: 10.1038/nrd1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrara N, Damico L, Shams N, Lowman H, Kim R. Development of ranibizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment, as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:859–70. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000242842.14624.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham ET, Jr, Adamis AP, Goldbaum M. Macugen® (pegaptanib sodium) for the treatment of ocular vascular disease. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishida S, Usui T, Yamashiro K, Kaji Y, Amano S, Ogura Y, et al. Vegf164-mediated inflammation is required for pathological, but not physiological, ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. J Exp Med. 2003;198:483–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishida S, Usui T, Yamashiro K, Kaji Y, Ahmed E, Carrasquillo KG, et al. Vegf164 is pro-inflammatory in the diabetic retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2155–62. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng E, Nishijima K, Robinson GS, Adamis AP, Shima DT. VEGF has both direct and indirect neuroprotective effects in ischemic retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4829. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, Feinsod M Guyer DR; VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization Clinical Trial Group. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization (V.I.S.I.O.N.) Clinical Trial Group. Chakravarthy U, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, Goldbaum M, Guyer DR. Year 2 efficacy results of 2 randomized controlled clinical trials of pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1508–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzales CR VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization (VISION) Clinical Trial Group. Enhanced efficacy associated with early treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with pegaptanib sodium: An exploratory analysis. Retina. 2005;25:815–27. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization (V.I.S.I.O.N.) Clinical Trial Group. D′Amico DJ, Masonson HN, Patel N, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr., et al. Pegaptanib sodium for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year safety results of the two prospective, multicenter, controlled clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:992–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suner IJ. Safety of pegaptanib sodium in age-related macular degeneration (AMD): 3-year results of the VISION trial. Poster presented at: The Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; November 11-14, 2006; Las Vegas, Nev. 2006. Poster 715. [Google Scholar]

- 14.the Macugen AMD Study Group. One-year systemic safety and pharmacokinetics of pegaptanib in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD). . In: Apte RS , editor. Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; November 11-14, 2006; Las Vegas, Nev. 2006. Poster 721. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham ET, Jr, Adamis AP, Altaweel M, Aiello LP, Bressler NM, D′Amico DJ, et al. A phase II randomized double-masked trial of pegaptanib, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor aptamer, for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamis AP, Altaweel M, Bressler NM, Cunningham ET, Jr, Davis MD, Goldbaum M, et al. Changes in retinal neovascularization after pegaptanib (Macugen) therapy in diabetic individuals. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez VH, Vann VR, Bandra RM, editors. Selective VEGF Inhibition: Effectiveness in modifying the progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). . Poster presented at: The Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; November 11-14, 2006; Las Vegas, Nev. 2006. Poster 309. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd SR, Zachary I, Chakravarthy U, Allen GJ, Wisdom GB, Cree IA, et al. Correlation of increased vascular endothelial growth factor with neovascularization and permeability in ischemic central vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1644–50. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.12.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Data on file, (OSI) Eyetech, Inc: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells JA, 3 rd for the Pegaptanib in Retinal Central Vein Occlusion Study Group. Safety and efficacy of pegaptanib sodium in treating macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO); Poster presented at: The Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; November 11-14, 2006; Las Vegas, Nev. 2006. Poster 370. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippopoulos T, Ducharme JF, Lowenstein JI, Krzystolik MG. Antiangiogenic agents as an adjunctive treatment for complicated neovascular glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4476. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trese MT, Capone A, Jr, Drenser K. Macugen in retinopathy of prematurity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2330. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drenser KA. Macugen therapy for the treatment of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy; Paper presented at: The Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; April 30-May 4, 2006; Ft Lauderdale, Fla. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes MS, Sang DN. Safety and efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab followed by pegaptanib maintenance as a treatment regimen for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2006;37:446–54. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20061101-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolentino MJ, Misch DM, Gerger AS. Avastin enhancement and Macugen maintenance therapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5912. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genentech, Inc. Health-care provider letter. [[Last accessed on 2007 Jan 30]. http://www.gene.com/gene/products/information/pdf/healthcare-provider-letter.pdf.

- 27.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M; Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, Boyer DS, Kaiser PK, Chung CY, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heier JS, Boyer DS, Ciulla TA, Ferrone PJ, Jumper JM, Gentile RC, et al. Ranibizumab combined with verteporfin photodynamic therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Year 1 results of the FOCUS Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1532–42. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.11.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]