Abstract

Background:

To report the anatomic and visual acuity response after intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in patients with diffuse diabetic macular edema.

Design:

Prospective, interventional case series study.

Materials and Methods:

This study included 20 eyes of metabolically stable diabetes mellitus with diffuse diabetic macular edema with a mean age of 59 years who were treated with two intravitreal injections of bevacizumab 1.25 mg in 0.05 ml six weeks apart. Main outcome measures were 1) early treatment diabetic retinopathy study visual acuity, 2) central macular thickness by optical coherence tomography imaging. Each was evaluated at baseline and follow-up visits.

Results:

All the eyes had received some form of laser photocoagulation before (not less than six months ago), but all of these patients had persistent diffuse macular edema with no improvement in visual acuity. All the patients received two injections of bevacizumab at an interval of six weeks per eye. No adverse events were observed, including endophthalmitis, inflammation and increased intraocular pressure or thromboembolic events in any patient. The mean baseline acuity was 20/494 (log Mar=1.338±0.455) and the mean acuity at three months following the second intravitreal injection was 20/295 (log Mar=1.094±0.254), a difference that was highly significant ( P =0.008). The mean central macular thickness at baseline was 492 µm which decreased to 369 µm ( P =0.001) at the end of six months.

Conclusions:

Initial treatment results of patients with diffuse diabetic macular edema not responding to previous photocoagulation did not reveal any short-term safety concerns. Intravitreal bevacizumab resulted in a significant decrease in macular thickness and improvement in visual acuity at three months but the effect was somewhat blunted, though still statistically significant at the end of six months.

Keywords: Diffuse diabetic macular edema, intravitreal bevacizumab, vascular endothelial growth factor

Diabetic macular edema (DME) continues to be the paramount cause of visual loss in diabetic patients. The visual impairment from untreated macular edema often leads to legal blindness and has a significant detrimental effect on the quality of life. In our country alone we have a staggering 31.7 million diabetics with a rising incidence, of which nearly 30% have some degree of retinopathy.1

Apart from laser photocoagulation, which is the primary treatment modality, intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) is being used commonly for the various forms of DME. 2, 3 It has been well established that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a vital role in promoting neovascularization and increased vascular permeability in diabetic eyes. Levels of ocular VEGF are correlated with both the growth and permeability of new vessels. 4 Furthermore, introduction of VEGF into normal primate eyes induces the same pathological processes as seen in diabetic retinopathy, namely micro aneurysm formation and increased vascular permeability. Also, studies have shown vitreous samples from patients with DME contain elevated VEGF levels. 5 Based on these facts anti-VEGF agents like pegaptanib sodium and ranibizumab have been evaluated for DME in Phase II randomized trials and a pilot study respectively with fairly promising results, especially for pegaptanib sodium. 6, 7

In the Phase II multicenter, dose ranging trial with pegaptanib, 172 patients were evaluated. The subjects assigned to pegaptanib had better visual acuity (VA) outcomes (34% versus 10%, P =0.003), were more likely to show reduction in central retinal thickness ( P =0.02) and were deemed less likely to need additional therapy with photocoagulation as compared with sham. 6

Compared to pegaptanib which is a modified 28-base ribonucleic acid aptamer that selectively binds VEGF165, bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits all active isoforms of VEGF. Intravitreal bevacizumab is a new treatment modality which is currently being tried out for use in macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), wet age-related macular degeneration (ARMD), rubeosis irides, proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and retinopathy of prematurity. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Although intravitreal use of bevacizumab is an off-label option its use has risen exponentially in the last few months mainly due to its efficacy and economic considerations.

Based on these observations we evaluated intravitreal bevacizumab in DME in which VEGF is known to play a key role in increasing vascular permeability and breaking down the blood retinal barrier.

Materials and Methods

In this prospective pilot study 20 eyes of 19 patients (10 females and nine males) with diffuse DME were given off-label intravitreal bevacizumab. Five eyes also had associated active proliferative diabetic retiniopathy (PDR). The administration of intravitreal bevacizumab was approved by the ethics committee. Patients with diffuse DME in fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), best corrected visual acuity ≤20/200, glycated hemoglobin ≤ 7.5 mg/dl were included. Eyes that had the following features were excluded: i) only focal macular edema attributable to focal leaks from micro aneurysm, ii) presence of any other macular pathology like ARMD or any vascular occlusive diseases affecting macula, iii) optic disc pathology due to chronic glaucoma, vi) previously treated with pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP) and grid laser within last six months, v) those with evidence of vitreomacular traction vi) angiographic evidence of widening or irregularity of the foveal avascular zone suggestive of ischemic maculopathy. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure and history of stroke were excluded from the study.

The number of anterior chamber cells observed in cases of ocular inflammation was determined by slit-lamp examination. Zero cells indicated that no cells were visible in any optical section when the slit-lamp beam (1x1 mm) was swept across the anterior chamber, trace cells indicated that one to three cells were observed, 1 + cells three to 10 cells, 2 + cells 10 to 25 cells, 3 + cells 25 to 50 cells and 4 + cells > 50 cells and or hypopyon present.

Each patient underwent best corrected distance VA measurement with early treatment diabetic retinopathy study (ETDRS) chart and ophthalmic assessment including slit-lamp biomicroscopy. All the patients underwent anterior segment examination, biomicroscopic evaluation with fundus non contact +90D lens and FFA. Central macular thickness was measured with optical coherence tomography (OCT III, Stratus OCT, Carl Zeiss, Germany).Three vertical and horizontal manually assisted OCT scans were obtained to locate the fovea and foveal thickness. The study parameters were evaluated three months and six months after the second intravitreal injection. The intravitreal dosage of bevacizumab was 1.25mg/0.05cc. All the injections were performed in a strict aseptic fashion and prophylactic topical antibiotics were given for five days post injection. Six weeks after first injection, reinjection was performed in a similar fashion. Study parameters included i) ETDRS visual acuity, ii) central macular thickness as measured by OCT and iii) incidence of side-effects which included rise in intraocular pressure (IOP), inflammation and endophthalmitis.

Systemically all the patients were monitored for blood pressure rise, chest pain and thromboembolic events (weakness in limbs).

Statistical analysis for descriptive statistics was performed using SPSS statistical software. The visual acuity was converted to logMAR before analysis.

Repeated measures analysis of variance test (2 ways ANOVA) was applied for the analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

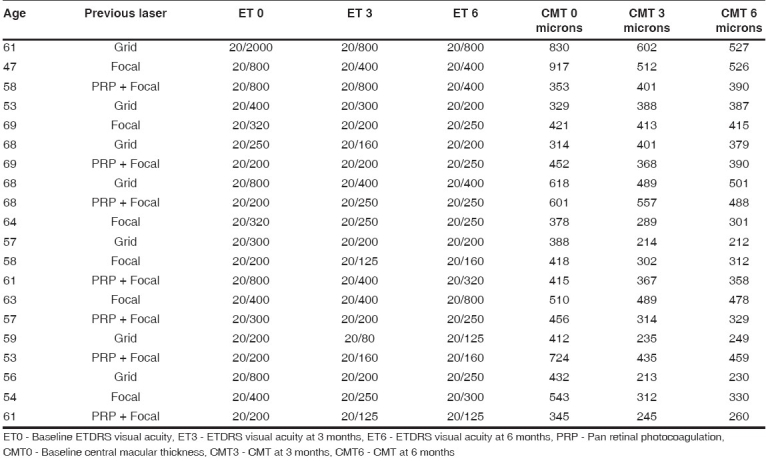

All the 20 eyes had received some form of laser photocoagulation previously as shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics included a mean VA of 20/494 (logMAR=1.338±0.455), mean central macular thickness of 492.8±167.2 µm and mean IOP of 15.33±2.7 mmHg. All the eyes had diffuse macular edema diagnosed by FFA and OCT at baseline.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics including visual acuity and CMT changes

Three-month outcomes

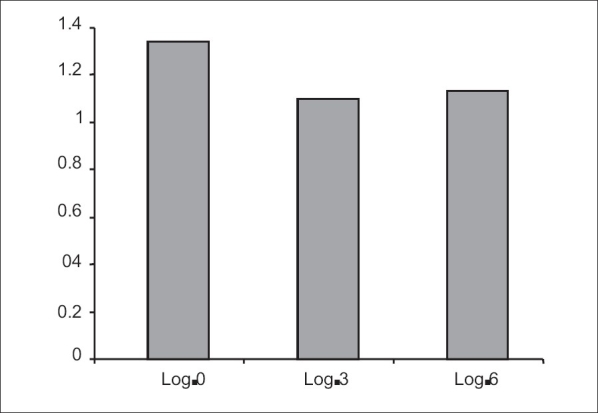

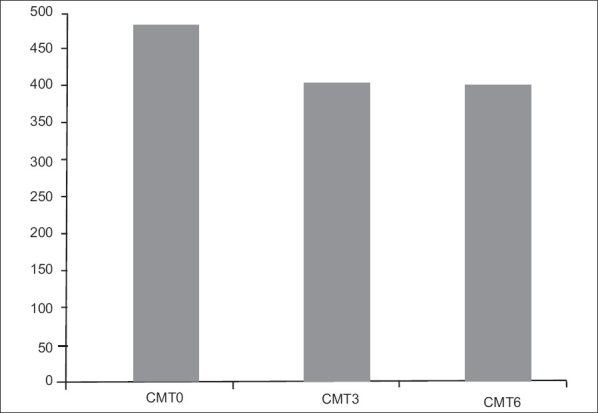

Statistically significant changes in VA and central macular thickness were observed at month 3 after second intravitreal injection. VA at month 3 improved to a mean of 20/295 (logMAR= 1.094±0.254), a difference from baseline that was highly significant ( P =0.008) [Fig. 1]. Mean central macular thickness at month 3 was 377.3±113.57 µ, a difference from baseline that was also highly significant ( P =0.001) [Fig. 2]. The mean IOP was 15.9 mmHg. There was no incidence of significantly raised IOP in any eye. No systemic adverse events were seen. None of the injected eyes had 2 + or more cells.

Figure 1.

Mean logMAR visual acuity at various time intervals

Log 0 - Mean baseline logMAR visual acuity

Log 3 - Mean logMAR visual acuity at 3 months

Log 6 - Mean logMAR visual acuity at 6 months

Figure 2.

Mean central macular thickness at various time intervals

CMT 0 - Mean baseline central macular thickness

CMT 3 - Mean central macular thickness at 3 months

CMT 6 - Mean central macular thickness at 6 months

Six-month outcomes

At month 6 after the second injection the mean VA was 20/304 (logMAR=1.124±0.219) [Fig. 1]. Though the mean VA worsened marginally the difference was still statistically significant compared to baseline ( P =0.029).The mean central macular thickness was 379±104 µ at the end of six months′ follow-up ( P =0.001) [Fig. 2]. The mean IOP was 16.6 mmHg at the end of six months.

During the entire follow-up of six months, there were no cases of clinically evident inflammation, endophthalmitis, increased IOP, retinal detachment.

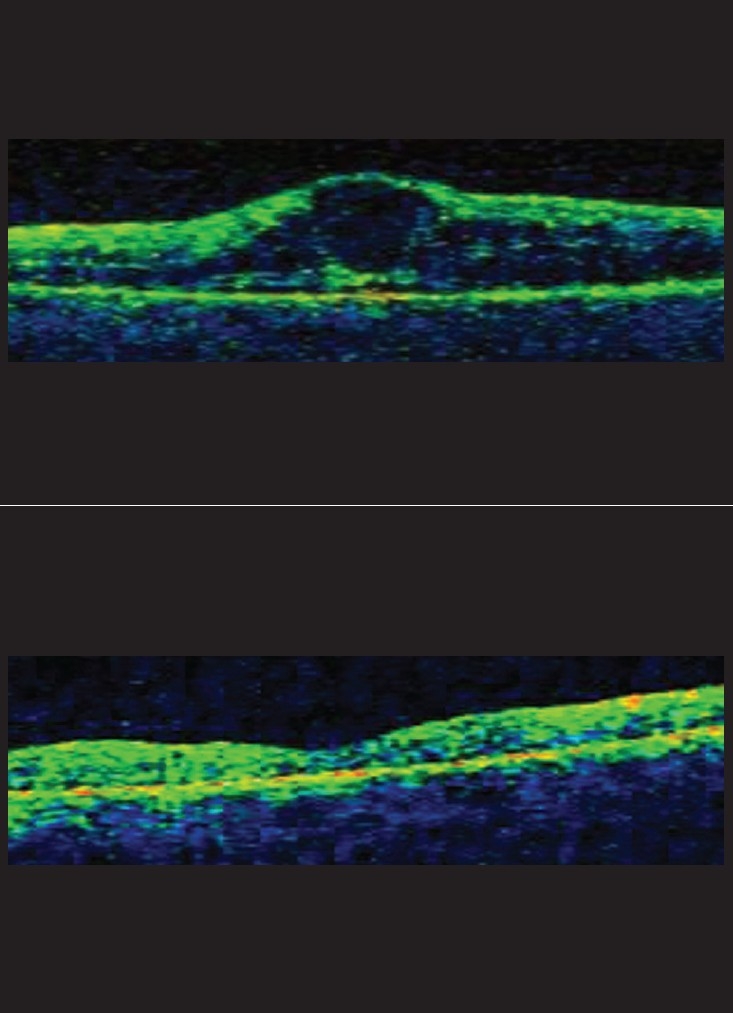

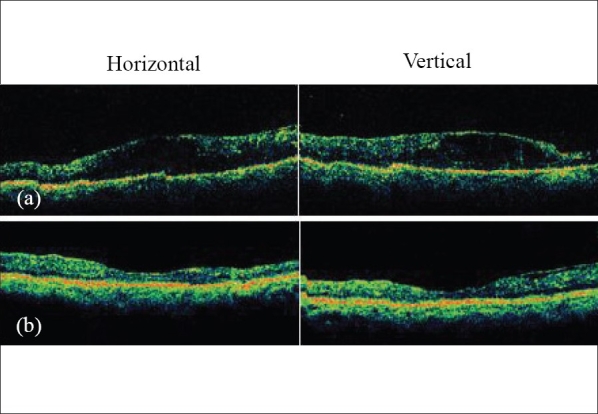

Figs. 3 and 4 show baseline and final OCT images of two separate eyes.

Figure 3.

a: Diabetic ‘cystic’ macular edema which received two intravitreal injections of Avastin six weeks apart. b: Normal foveal contour with resolution of edema at six months post Avastin injection

Figure 4.

(a) Pre-avastin diabetic macular edema with gross intraretinal fluid (horizontal and vertical OCT scan); (b) Resolution of edema six months after two consecutive 1.25 mg intravitreal Avastin injections given six weeks apart

Discussion

We report the results of 20 consecutive eyes with diffuse DME treated with intravitreal bevacizumab which resulted in both anatomic and functional improvement. Our results also show that bevacizumab was well tolerated and no systemic adverse events were noticed during the study. Ocular tolerance was also high and no ocular inflammation was noted.

Intravitreal steroids reduce macular edema for which several theories were proposed, including local reduction of inflammatory mediators, lower levels of VEGF, increased diffusion by an effect on calcium channels and improved blood retinal barrier function; 19 it however remains plagued by a considerably high percentage of side-effects, namely cataract progression in a number of eyes and rise in IOP (10 to 50%). 3

Recently, the results of a Phase II study of pegaptanib have been reported with encouraging results for eyes with DME. 6 A strict comparison between safety, efficacy and end points of bevacizumab and pegaptanib is not possible because of the limited number of patients, study size and study design. However, in a limited comparison of adverse events, intravitreal bevacizumab appears to have a profile comparable to that of pegaptanib injection.

Another finding that had surfaced during this study, which has already been shown by other studies, is the prompt regression of neovascularization in the five eyes with active PDR. These eyes underwent a milder form of PRP four to six weeks post intravitreal bevacizumab injection.

In this small study which was carried out in an Indian population, the mean central macular thickness reduced to 369 µ from 492 µ and the visual acuity also showed a modest improvement from a baseline of 20/494 to 20/295 at the end of six months.

Bevacizumab has already been used for DME. 20 The capillary permeability seen in DME is secondary to release of VEGF, primarily VEGF-A whose release is inhibited by the pan anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, Avastin. 4

Similar to the study published by Haritoglou et al. , 20 our study also demonstrated significant improvement in VA and decrease of central macular thickness after two intravitreal bevacizumab injections. But in contrast to their study (six weeks follow-up) our study population was more homogenous and we followed up all the patients for six months. We also monitored for any post injection ocular inflammation in the form of anterior chamber cells and any systemic adverse events caused by bevacizumab. Additionally, our study show the beneficial effect of intravitreal bevacizumab in patients with DME associated with active PDR. The PRP laser requirements were reduced in this subset of patients following the intravitreal injection.

Our preliminary study provides evidence that inhibition of VEGF associated with both pathological ocular neovascularization and increased retinal vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy may produce a clinically meaningful and statistically significant benefit in the treatment of DME.

Though the positive results of this prospective, nonrandomized study preclude any estimation of the long-term efficacy or safety of intravitreal bevacizumab, they are quite promising and suggest the need for further longer prospective randomized studies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes, estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonas JB, Kamppeter BA, Harder B, Vossmerbaeumer U, Sauder G, Spandau UH. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for diabetic macular edema: A prospective, randomized study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2006;22:200–7. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.22.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstantopoulos A, Williams CP, Newsom RS, Luff AJ. Ocular morbidity associated with intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide. Eye. 2007;21:317–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, Keyt BA, Jampel HD, Shah ST, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1480–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT, D′Amico DJ, Folkman J, Yeo TK, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham ET, Adamis AP, Altaweel M, Aiello LP, Bressler NM, D′Amico DJ, et al. A phase II randomized double-masked trial of pegaptanib, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor aptamer, for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun DW, Heier JS, Topping TM, Duker JS, Bankert JM. A pilot study of multiple intravitreal injections of ranibizumab in patients with center-involving clinically significant diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1706–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iturralde D, Spaide RF, Meyerle CB, Klancnik JM, Yannuzzi LA, Fisher YL, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion: A short term study study. Retina. 2006;26:279–84. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spandau UH, Ihloff AK, Jonas JB. Intravitreal bevacizumab treatment of macular oedema due to central retinal vein occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:555–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaide RF, Laud K, Fine HF, Klancnik JM, Jr, Meyerle CB, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:383–90. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000238561.99283.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich RM, Rosenfeld PJ, Puliafito CA, Dubovy SR, Davis JL, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Short-term safety and efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:495–511. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000225766.75009.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ladewig MS, Ziemssen F, Jaissle G, Helb HM, Scholl HP, Eter N, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologe. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00347-006-1352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spaide RF, Fisher YL. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy complicated by vitreous hemorrhage. Retina. 2006;26:275–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oshima Y, Sakaguchi H, Gomi F, Tano Y. Regression of iris neovascularization after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:155–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakri SJ, Donaldson MJ, Link TP. Rapid regression of disc neovascularization in a patient with proliferative diabetic retinopathy following adjunctive intravitreal bevacizumab. Eye. 2006;20:1474–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaide RF, Fisher YL. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy complicated by vitreous hemorrhage. Retina. 2006;26:275–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason JO, Albert MA, Jr, Mays A, Vail R. Regression of neovascular iris vessels by intravitreal injection of Bevacizumab. Retina. 2006;26:839–41. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000230425.31296.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah PK, Narendran V, Tawansy KA, Raghuram A, Narendran K. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for post laser anterior segment ischemia in aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:75–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.29505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vedantham V, Kim R. Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide for diabetic macular edema: Principles and practice. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:133–7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.25840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haritoglou C, Kook D, Neubauer A, Wolf A, Priglinger S, Strauss R, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) therapy for persistent diffuse diabetic macular edema. Retina. 2006;26:999–1005. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000247165.38655.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]