Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate teaching and practice in medical college ophthalmology departments in a representative Indian state and changes following provision of modern instrumentation and training.

Study Type:

Prospective qualitative study.

Materials and Methods:

Teaching and practice in all medical colleges in the state assessed on two separate occasions by external evaluators. Preferred criteria for training and care were pre-specified. Methodology included site visits to document functioning and conduct interviews. Assessments included resident teaching, use of instrumentation provided specifically for training and standard of eye care. The first evaluation (1998) was followed by provision of modern instrumentation and training on two separate occasions, estimated at Rupees 34 crores. The follow-up evaluation in 2006 used the same methodology as the first.

Results:

Eight departments were evaluated on the first occasion; there were 11 at the second. On the first assessment, none of the programs met the criteria for training or care. Following the provision of modern instrumentation and training, intraocular lens usage increased dramatically; but the overall situation remained essentially unchanged in the 8 departments evaluated 8 years later. Routine comprehensive eye examination was neither taught nor practiced. Individually supervised surgical training using beam splitters was not practiced in any program; neither was modern management of complications or its teaching. Phacoemulsification was not taught, and residents were not confident of setting up practice. Instruments provided specifically for training were not used for that purpose. Students reported that theoretical teaching was good.

Conclusions:

Drastic changes in training, patient care and accountability are needed in most medical college ophthalmology departments.

Keywords: Change, funding, India, instruments, medical college departments, ophthalmology residency programs, training

The training of ophthalmologists in medical college departments is crucial to combat the blindness in our country.1-4 It is important that residents be trained in modern examination, diagnostic and surgical techniques. Additionally, training and eye care in teaching departments should conform to modern standards and follow preferred practice patterns. It is however well known that most newly qualified Indian ophthalmologists are compelled to seek additional training, even in modern cataract surgery.3

With a view to improving the quality of cataract surgery and eye care, the government of India and the World Bank supported a program to convert surgeons to extra-capsular cataract surgery with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation.5,6 The World Bank ′funding,′ however, was not a grant but was a loan that the Indian taxpayer paid for. It would be desirable, therefore, to incorporate modern ophthalmic techniques into residency training programs, obviating the need for ′catch-up′ loans for future upgrades.

While the status of Indian residency training programs has been mentioned, to the best of our knowledge there are no reports on the functioning of these medical college departments.3,4,7,8 We report the assessment of teaching and care in the medical college ophthalmology departments in one representative state in the country. The evaluation was repeated 8 years later following two ′grants,′ first by the World Bank (approximately Rs. 28 crores) and then by a local body (Rs. 6 crores), 6 years apart, towards state-of-the-art ophthalmic instrumentation and training in their use.

Materials and Methods

All medical college departments of ophthalmology in a representative state of the country were evaluated by two external assessors. The state was chosen for convenience; logistical ease; and the fact that it was one of the beneficiaries of the World Bank program, as well as of a second round of funding by a local body. The first visit was undertaken by RT and the second by MD. The data were accumulated during two evaluations performed 8 years apart. While the second evaluation was ′suggested′ at the end of the first study, it was not part of the plan when the first assessment took place. However, the methodology, as well as the data collected during the second study, was based on the first.

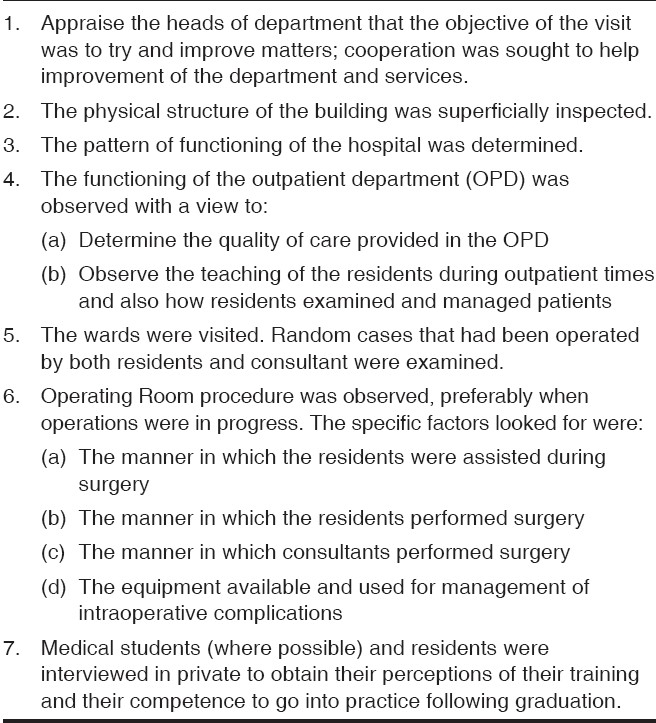

Eight medical college departments were evaluated during the first visit. During the ensuing years, 3 more departments had developed; and a total of 11 departments were evaluated during the second phase. A structured questionnaire [Appendix 1, 2] was sent out in advance to the respective heads of department to determine details like the number of students, patients seen, operations done and list of the equipment available. Following this, the evaluator scheduled a site visit and spent a day in each of the departments. Details of the programs were personally collected and entered by the evaluator. The activities undertaken during this visit are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

On-site activities undertaken by the evaluator

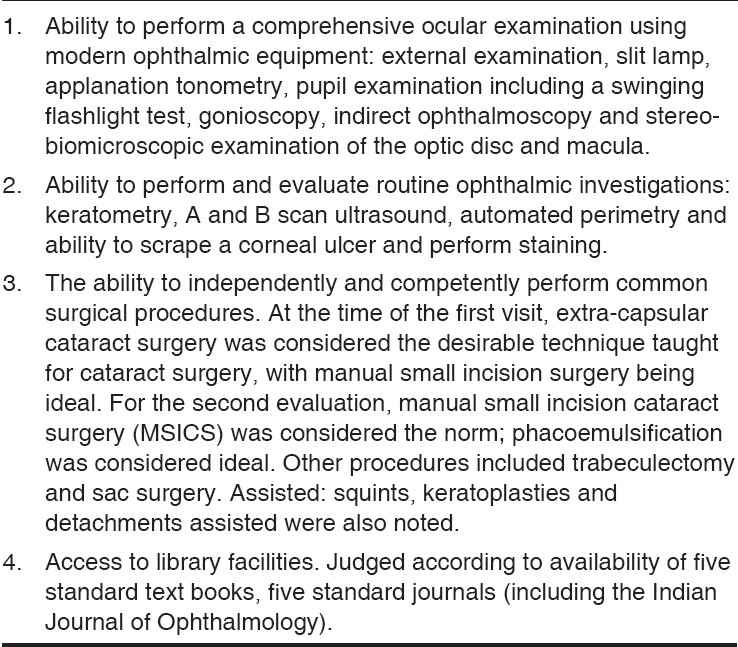

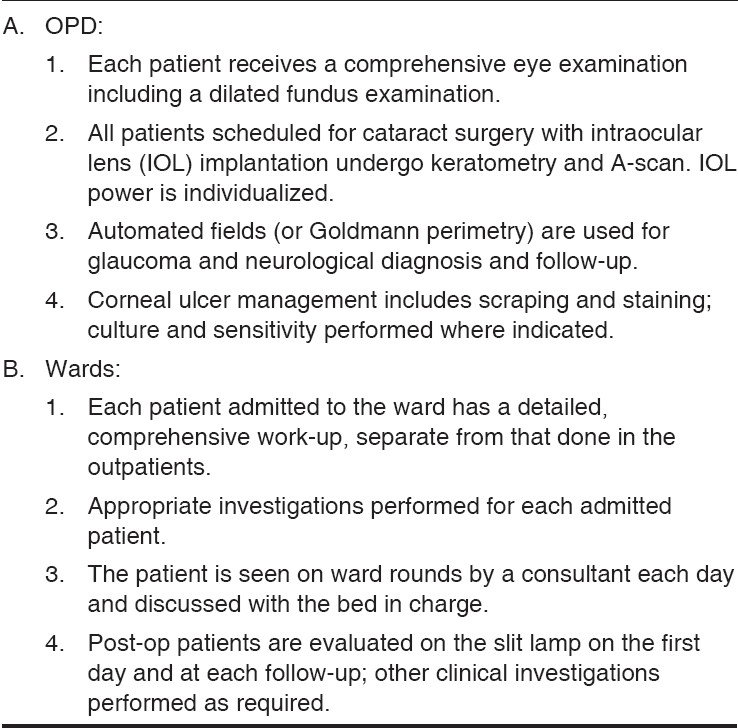

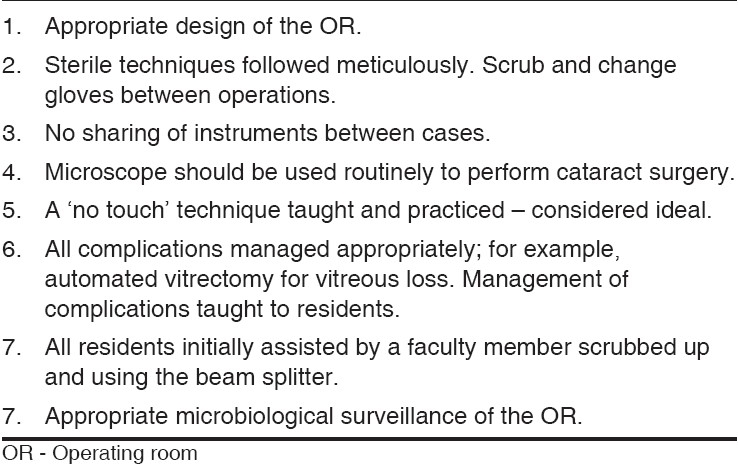

The preferred characteristics of an ophthalmology training program were specified in advance and were the considered opinion of the first evaluator and agreed to by the second prior to the next evaluation. The features considered essential for resident training are shown in Table 2. The criteria considered indicators of suitable outpatient and ward care in a medical college department are shown in Table 3; those for the operating room are shown in Table 4. Undergraduate training was assessed using a questionnaire, observation and personal interview only during the first evaluation.

Table 2.

Features considered essential for resident training

Table 3.

Criteria considered indicators of suitable eye care in outpatient department (OPD) and ward

Table 4.

Criteria for suitable eye care in the operating room

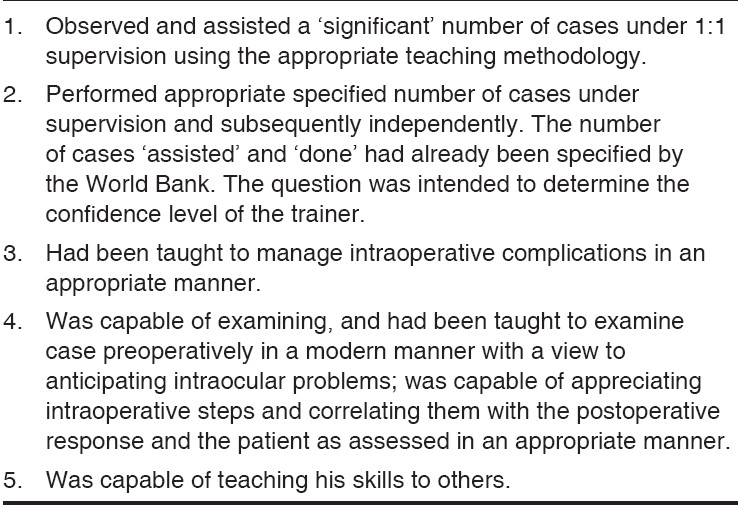

At the time of the first visit, the World Bank training program was underway. Fourteen ′trainer of trainers′ who had been trained by the World Bank program were interviewed. The questions asked are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Questions for the trainer of trainers

Changes in teaching and practice pattern, including surgery, instrumentation and their use, were documented for the eight departments examined on the two occasions. For the three newer departments, only their current functioning was detailed. The nature of the data permitted only a descriptive analysis.

Results

First evaluation (1998)

The number of outpatients seen in the departments varied from 95 (70 new and 25 old) to 1,300 (800 new, 500 old) per month. The number of beds varied from 16 to 500; and the number of ophthalmologists in each department, from 4 to 46. The number of residents (DO and MS) ranged from 4 to 16. One department was only training undergraduates. Three departments with residency programs had no slit lamps; the maximum number of functioning slit lamps in a department was 10. Two departments did not have indirect ophthalmoscopes; five departments had one to two in working order, while one department had six. Only one department had a functioning A-scan. The number of cataracts done each year varied from 234 to 8,371; cataracts with intraocular lenses (IOLs) were 20 to 5,600.

None of the criteria considered necessary for patient care in a teaching department were routine in any of the departments. None of the criteria for resident teaching were met in any of the departments. A brief description follows.

Most departments had an adequate outpatient load, but patients were managed (and teaching undertaken) between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. None of the departments practiced a routine comprehensive eye examination. This concept was not taught to residents either. Routine tonometry (even Schiotz) and fundus examination were not the norm. Patients were dilated only rarely. This practice was prevalent even in the only hospital that had all the essential equipment for teaching. None of the departments had an automated perimeter. The Goldman perimeters available in some departments were unused. Bjerrum′s screens were not used either. The examination pattern in all hospitals could best be described as what would be considered routine in an ′eye camp.′ While there was clinical teaching, the residents did not manage patients ′independently′ or even under supervision. They mainly observed the proceedings and participated in formal case discussions. This pattern was true even in the only department that had most of the modern ophthalmic instrumentation.

There were several reports of essential instrumentation being ′locked up′ without access for residents, and, in some instances, even the faculty. In one department, there was a well-preserved 10-year-old indirect ophthalmoscope reported to be in ′routine use.′ The original bulb was still functioning.

The operating room (OR) design was unsuitable in six of the departments. The sterile area and procedures were violated in most ORs. While most surgeons scrubbed between cases, the gowns were not changed throughout the day; gloves were not used. A ′no touch′ technique was not used in any department. Surgeons with the training and skills to perform microsurgery could not do so, due to lack of instrumentation. If a microscope was available, only some surgeons were allowed to use it. Magnification for cataract surgery was not the norm; in one department, a 2-year-old child had undergone an IOL implantation without any magnification. A-scans were not routine in the only department that had one. Postoperative slit lamp examinations were not the norm.

Undergraduates had regular theory and clinical teaching. In one department, findings were demonstrated on the slit lamp. The evaluator was impressed by the intelligence of, and the interest shown by, the residents interviewed – which he put on record. The residents too were happy with the theoretical teaching. They all felt they got enough cataracts to do. The number of intra-capsular operations performed during the course ranged from 15 to 150; extra-capsulars, from 0 to 300; and IOLs, from 0 to 25. Residents were not supervised in the recommended manner during surgery. None of them had been taught an automated vitrectomy. There was no training in glaucoma or other types of operations listed. Only one of the residents interviewed felt confident about going into practice immediately after graduation.

Intervention: The World Bank program spent approximately Rs. 56 crores for instrumentation, training and other costs in the chosen state. We assumed that approximately half of this, that is Rs. 28 crores, was used for instrumentation and training. The instrumentation provided included slit lamps with applanation tonometers, teaching microscopes, A-scans and other basic instrumentation. About 5 years later, a local funding body provided an additional Rs. 6 crores for state-of-the-art instrumentation - including high-quality surgical microscopes, slit lamps with applanation tonometers, phacoemulsification machines, additional A-scans, fundus cameras, lasers (Yag and green), automated perimeters and audiovisual equipment. Each department also received state-of-the-art teaching surgical microscopes and slit lamps with beam splitters, stereo observer-scopes and monitors provided specifically for teaching purposes. In other words, the departments were as well equipped as any medical college department anywhere in the world could be.

Second evaluation (2006)

The number of doctors, postgraduates, beds and patients seen remained almost at the same level between the two visits.

The head of departments reported that instrumentation provided was used ′frequently′ in 4 of the 11 departments. One head of department stated that patient care and teaching had improved considerably. All felt that the audiovisual equipment had improved the teaching and student presentations. However, the criteria of care and teaching considered appropriate for medical colleges [Tables 2-4] were not achieved. The timings for patient management and teaching were still 9 a.m. to 2 p.m.

A comprehensive eye examination was still not the norm and was not routinely undertaken by the residents or faculty. Resident interviews revealed that the residents were not allowed to use diagnostic instruments provided for training. Applanation prisms were locked up, as were diagnostic lenses. Resident interviews also revealed that while the residents now used microscopes for surgery, the recommended supervision was lacking. The teaching microscopes with the beam splitters and monitors were not made available to postgraduates; in some cases, not even to faculty. Diagnostic instruments were still ′locked′ up.

In two departments the teaching slit lamps were used for demonstrations for undergraduates and residents, but residents did not get to use the newer equipment provided. One department used the fundus camera daily. Two others had done three fluorescein angiographies in the last year. Laser machines were unused or sparingly used (two lasers in a year). High-end automated perimeters were available; but as they were sparingly used, fields were not preformed for all glaucoma suspects or cases. Phacoemulsification machines were still in their packing in three departments, and phacoemulsification was not the norm in any of the hospitals. None of the residents had been taught phacoemulsification. Some had performed manual small incision cataract surgery (SICS). A-scans were available in all the departments but were not routine for all IOL surgery.

The surgical pattern had changed in that IOL usage was now the norm (91 to 99%). Other surgical practices, however, remained the same and actual visual outcomes were not known. An automated vitrectomy was still not routine for vitreous loss. Routine postoperative slit lamp examination was still not the norm.

At the time of both the visits, patients were not informed about the examinations, investigations or procedures they were about to undergo. An informal discussion of risks and benefits or a formal informed consent was not the norm and was not witnessed during either visit.

The trainer of trainer (TOT) issue was addressed formally only at the first visit, but, as will be seen, still has relevance. The trainers interviewed had been trained in one of the three centers. All were happy with their training. They had independently performed the minimum number of cases stipulated by the World Bank. Only one training institution taught what would be considered the appropriate evaluation (required of a trainer) necessary to diagnose and manage potential problems. Training using a microscope with beam splitters was not imparted in most instances. Additionally, only one institution taught ′trainers′ appropriate management of vitreous loss. A ′no touch′ technique was not taught in any institution to the trainers or students. All 14 ′trainers of trainers′ who had returned to their parent institutions and were interviewed were male.

Following their return from the TOT program, till the first evaluation took place, none of the trainers had taught a single person. Some were doing IOLs in the department but not teaching it. However, most were doing IOLs in the private sector. One trainer on his return was posted to the biochemistry department.

Teachers interviewed during the second visit felt their training was insufficient to enable them to confidently use, and teach the use of, the instrumentation provided. Many were uncomfortable with performing or teaching phacoemulsification as they did not have the wherewithal to manage complications. Overall, most felt they required more training. Some of them did, however, use the instrumentation (and perform phacoemulsification) in private practice. As far as inappropriate postings were concerned, the second evaluator too reported that many ophthalmologists trained in microsurgery were posted to departments of anatomy, microbiology and radiology even when trainers were not available in the parent department of ophthalmology.

Discussion

Residency training is crucial for the future of Indian ophthalmology, as well as for the delivery of quality eye care to the population. We are aware of the constraints under which the publicly funded medical college departments function; however, there are public and private departments in the country that can compete with the best in the world. Therefore, the objective was to compare the training programs to what is possible in the country. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports of on-site evaluation of residency training in India.

The residents were happy with the theoretical training. The teachers felt that with the provision of audiovisual equipment, student presentations had improved dramatically. Also, IOL usage in all departments had increased dramatically and had become the norm. The visual outcomes of this advance and the occurrence of complications were however not available. Nevertheless, teaching standards and care delivery in all medical college departments failed to meet the specified benchmarks, at both the evaluations, performed after the provision of quality equipment (and training in their use) on two separate occasions. This was true both for teaching as well as for management of patients. The provision of instrumentation and training had not effected the desired changes.

What should our training philosophy be? Patients treated in training departments participate in the learning process. It behooves us then to ensure that the probability of best possible outcomes is maximized. This can only be achieved if all patients are carefully examined not just from the training point of view, but also from the view of selecting (at least, at first) uncomplicated cases for training. This critical selection cannot be achieved by a flashlight and intuition. Additionally, all surgery in such situations must be taught by experienced surgeons using the recommended instrumentation; for the initial cases, this requires an experienced surgeon scrubbed up and actively assisting through the observer scope. Furthermore, all complications in a training situation must be managed in the best possible manner to minimize morbidity and maximize acceptable outcomes. The student must be taught the management of complications. This too requires an experienced surgeon assisting the student, using accepted modern instrumentation. Management of complications extends well into the postoperative period and mandates routine postoperative slit lamp and fundus examination. Such routine pre- and postoperative examinations, assistance during surgery and management of complications (and its teaching) did not exist in any of the departments.

The faculty in some departments indicated that students ′routinely′ used slit lamps, applanation tonometers, gonioscopes and indirect ophthalmoscopes. In all departments, however, the residents told a different story. They were not allowed to use instruments specifically provided for them, and some diagnostic instruments were locked up to prevent access for anyone. They were not taught to perform routine comprehensive eye examination and did not manage cases either under supervision or independently.

While not a part of the checklists, an important aspect of modern eye care is informed consent and patient participation in the treatment. This was not practiced in any department; unless it is part of patient care in teaching departments, students are unlikely to understand its importance and employ it in practice. In a training department, this ethical aspect becomes even more demanding. Ideally patients should be informed that they may be operated on by a trainee or at least be informed that they will not have the choice of surgeon. Research methodology is another important component of postgraduate teaching, especially if we want to encourage ophthalmic research in India. This was not formally taught in any program. The paucity of publications from most medical college departments would seem to be a direct consequence.8

The reasons for lack of appropriate teaching and eye care are complex. One reason could be issues with the training of trainers and is discussed below. Another cause could be the limited working hours. The usually large patient loads cannot be appropriately managed and teaching undertaken in a 5-hour day. The issues of private practice and nonpracticing allowance responsible for such limited working hours need urgent resolution. On the other hand, an increase in working hours may not guarantee that desired benchmarks will be achieved. (There are states where the working hours are longer but the patient care and practice is similar.) Another unlikely, purely theoretical possibility is poor leadership, improper attitude and lack of accountability. Measures to identify and address the source of the problem and ensure appropriate teaching and preferred practice are urgently needed.

As far as modern ophthalmology is concerned, the existing archaic guidelines for the recognition and continued accreditation of teaching departments need major restructuring. Programs without the necessary instrumentation, teaching and practice required for modern ophthalmology are ′recognized′ for training. On the other hand, we are aware of one well-functioning modern teaching department (fulfilling all the benchmarks) that was not ′recognized′ as it was not split into ′units′ and had ′too many beds.′ It would seem that the rules require units and beds, not instrumentation, teaching or preferred practice patterns. Interestingly, while modern ophthalmology hardly requires ′beds′, provision of such beds in teaching departments may actually be desirable. Postgraduates could then at least be responsible for the care of patients on their beds; if undertaken and supervised properly, the work-up, investigations and intervention on their ′own′ patients is one way to ensure examination, management and follow-up skills. To ensure modern requirements, the final postgraduate examination to certify ophthalmologists too needs major change. The clinical component of the examinations should at least observe and test competence in the components of a comprehensive eye examination and clinical (including surgical) ability, not just theoretical knowledge as is currently the case.

The TOT became accepted terminology during the ′World Bank′-funded program. During the planning of this program, Indian experts had stressed the need for placement of quality training equipment in the parent department before the TOT returned. They also expressed concern about maintenance of equipment and the potential for transfers of the TOT before the objective of the program was achieved. In reality, the promised equipment for training was not available on return in any of the parent departments. A TOT who was waiting for 6 months for the basic equipment dourly expressed the need for a ′refresher′ course. TOT was to be the backbone of the modern training process; yet their training too was below par. A ′no touch′ technique was not taught to any of them. This technique is desirable in all cataract surgery but becomes especially important in less-than-ideal conditions, especially where gloves are not used: the existing situation in all departments. And once in their parent departments, the TOTs did not or could not function to the desired potential.

The report generated at the end of the first evaluation recommended the provision of quality teaching instruments in all medical college departments, as well as measures to improve training and care delivery. The crucial aspect of maintenance and budget for spare parts was highlighted. The issues faced by the TOTs were specially highlighted with possible solutions. To the best of our knowledge, this report was available to all policy makers. The lessons of the World Bank program notwithstanding, the condition remained the same after the next round of funding. Expensive new instrumentation, including field analyzers, lasers, fundus cameras and phacoemulsification machines, lay unused even a year after it had been provided. Lack of training was again one factor mentioned by those interviewed. Further training may indeed be needed; however, even those who were trained did not transfer their skills to others in the department or their students. Modern procedures performed in private practice were neither undertaken nor taught in the teaching department. The use of beam splitters in microscopes usually warrants no extra training. Other reasons cited included fear of spoiling the new instruments, lack of spares and maintenance support. The practice of trained staff being deputed out to unrelated departments too continued over the years.

The study has several limitations. The second evaluation was not part of the original plan but serendipitously provided follow-up information. While the same evaluator would have been desirable for both assessments, logistical and other constraints mandated another assessor. Although the format and benchmarks used were the same for visits, the methods did vary and precluded some comparisons. We felt that the use of checklists helped avoid potential bias.

We assumed that half of the Rs. 56 crores allotted to the state by the World Bank was used for instrumentation and training. The actual amount might have been less than this. We accept that the first estimate may be wrong (in either direction) but highlight that an outlay was provided for instrumentation and training on two temporally separated occasions and have reported the impact of that investment on teaching and care.

The study state was chosen for convenience, logistics and because it was a beneficiary of World Bank and other funding. It is however a ′representative′ state of the country, and we feel that the data can be extrapolated to most medical college teaching departments. The standards in the country do vary dramatically, and there are some departments that not only meet but also exceed the benchmarks.

Some may consider the quality benchmarks as too strict for a ′developing′ country. We feel that this pretext has been used to maintain status quo for too long. We argue that at least in departments responsible for the training of future ophthalmologists, this overused ′developing country′ justification is no longer valid. The benchmarks used are not unrealistic; they have been achieved in the country and are eminently desirable.

In conclusion, the postgraduate programs do not train residents in modern ophthalmic examination and surgical techniques. The residents were not taught current cataract surgical techniques and were not confident of independent practice. The quality of care in the teaching departments did not conform to accepted preferred practice patterns. Finally, two rounds of funding totaling about Rs. 34 crores towards modern instrumentation and training did not materially change the standard of training and care.

The state of affairs has been an open secret for a long time. While there may be denials, accusations, recriminations and inaction, we hope that publication in our journal will help the ophthalmic community to acknowledge the problems, encourage dialog and initiate changes that ophthalmology training in India so obviously and desperately needs.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Survey on Blindness and visual outcomes after cataract surgery 2001-2002: Report published by National Programme for Control of Blindness. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, McCarty CA, Nanda A, Srinivas M, et al. Is current eye-care-policy focus almost exclusively on cataract adequate to deal with blindness in India? Lancet. 1998;351:1312–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas R, Paul P, Rao GN, Muliyil JP, Mathai A. Present status of eye care in India. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:85–101. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas R, Paul P, Muliyil J. Glaucoma in India. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:81–7. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200302000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose R, Bachani D. World bank-assisted cataract blindness: Control project. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1995;43:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkataswamy G. Combating cataract. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1995;43:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R. The role of SICS in the Indian scenario. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:[In press]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Bachani D, Sanga L, John N, Tewari HK. Status of specialty training in ophthalmology in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:135–42. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.16182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]