Abstract

We report a case of Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis in a 53-year-old, well-controlled diabetic female who did not respond to standard antifungal treatment. She was started on topical natamycin eye drops, but the infiltrate continued to progress. Topical amphotericin B and systemic ketoconazole was added, however, there was no response and the infiltrate increased further. She was then switched to topical and systemic voriconazole. Steady resolution of the infiltrate was noted within 2 weeks of therapy.

Keywords: Aspergillus, fungal keratitis, voriconazole

Fungal keratitis is a leading cause of ocular morbidity; one report from South India found that 44% of all central corneal ulcers are caused by fungi.1,2 Isolated pathogens vary with the geographic area studied.3 Yeast, especially Candida predominate in the temperate regions, whereas tropical isolates are mostly filamentous fungi. In India, filamentous fungi are the major etiologic agents of fungal keratitis. Fusarium and Aspergillus species are the most commonly implicated pathogens.2-5

Therapy of fungal infections, both ocular and systemic, can be difficult and prolonged. Challenges include limited number of antifungal agents, fungistatic nature of the available antifungals and poor tissue penetration of previously investigated agents. Voriconazole (Vfend; Pfizer Pharmaceuticals) is a new triazole antifungal agent, with the broadest spectrum of antifungal activity.6-10 The purpose of this case is to report that voriconazole has worked effectively in a patient with Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis, which did not respond to standard antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 53-year-old female came to us with history of foreign body entry in the left eye. Renovation of her house was underway and the exact nature of the foreign body was not known to her; however, she washed her eyes with plenty of tap water to get rid of it. She presented to us the next day with a large central corneal epithelial defect 7 mm × 6 mm in size, there was no infiltrate, there were two old corneal scars in the midperipheral cornea, she was treated with topical gatifloxacin and homatropine. The epithelial defect reduced, she was symptomatically better on the following day; however, on the third day, she developed a superficial corneal infiltrate with hyphate edges 2 mm × 1 mm and a satellite lesion [Fig. 1], visual acuity was 20/40, clinically it appeared to be a fungal infection. Our patient was a family physician herself and was explained the need for a corneal scraping [Fig. 2]; she insisted that we give empirical treatment with an antifungal medication and scrape only, if there was no response. She was treated with 5% natamycin eye drops half hourly along with homatropine eye drops thrice a day and gatifloxacin eye drops four times a day, also epithelial debridement was done regularly in view of poor corneal penetration of topical antifungal agents. After showing an initial response to the treatment [Fig. 3], the infiltrate increased in size and density, corneal scraping revealed filamentous fungus, cultures grew Aspergillus fumigatus [Fig. 4]. Since she had worsened despite 2 weeks of natamycin, we added topical amphotericin B 0.15% and systemic ketoconazole 200 mg twice a day. She gave history of diabetes since 3 years, which was well controlled, liver functions and renal functions were within the normal range and she had no history of any other systemic illness. Since the infiltrate kept increasing even with combined natamycin and amphotericin B therapy over the next 10 days [Fig. 5], we started her on topical voriconazole 1% every hour and systemic voriconazole 400 mg twice a day was given as loading dose on the first day followed by 200 mg twice a day. There was a steady resolution of the infiltrate in 2 weeks; topical voriconazole was tapered slowly over 2 months; oral therapy was discontinued by the end of 3 months, when the lesion scarred completely [Fig. 6] and vision was 2/60. There were no adverse events other than mild photosensitivity; liver function tests were repeated every 4 weeks and remained normal.

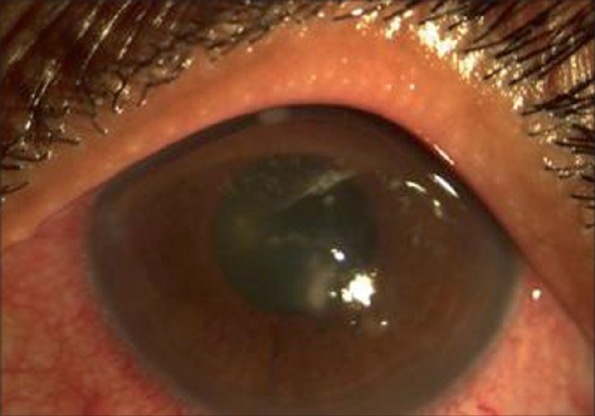

Figure 1.

Central infiltrate with hyphate edges, two old scars towards 11 o'clock and 5 o'clock

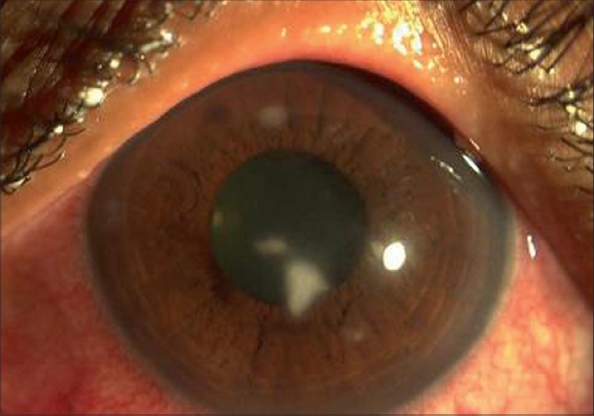

Figure 2.

Increase in the infiltrate size and density, necessitated scraping

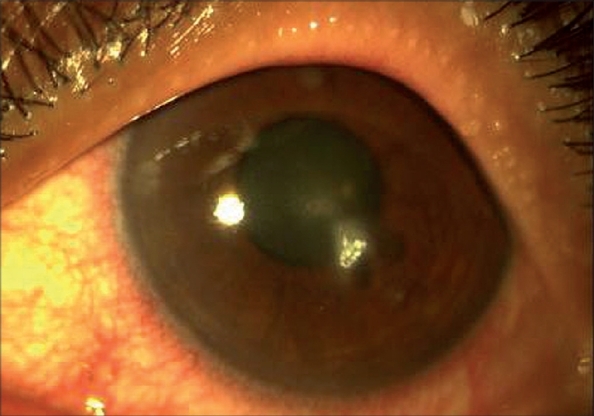

Figure 3.

On day 7 of natamycin eye drops, initial response to empiric treatment seen, natamycin precipitate present on the ulcer bed

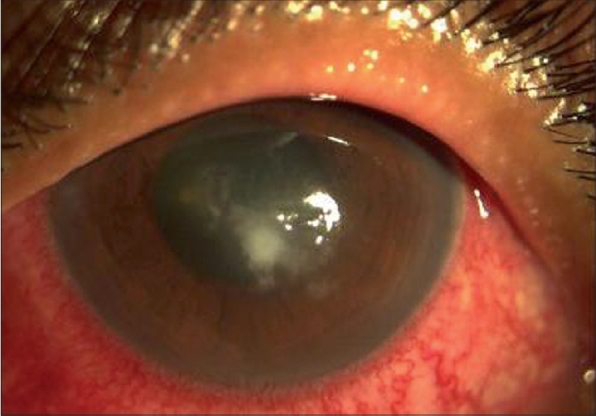

Figure 4.

Day 14 of natamycin eye drops worsening of infection, corneal scraping reveals fungal filaments

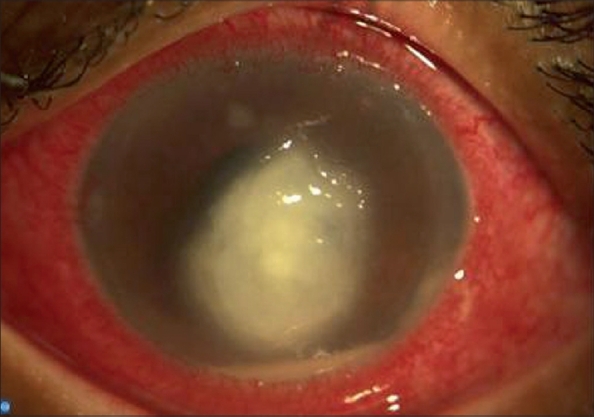

Figure 5.

Day 27 of natamycin and day 11 of amphotericin, progression of the infiltrate despite the combination, voriconazole started

Figure 6.

After 3 months of voriconazole treatment, central corneal scar

Discussion

Aspergillus is a filamentous and ubiquitous fungus found in nature, commonly isolated from soil, plant debris and indoor air environment. It is known to cause opportunistic infections, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. Any organ system in the body may be involved. As with other filamentous fungi, most cases of Aspergillus keratitis have a history of trauma, particularly with vegetable matter.2-5

Voriconazole is a triazole antifungal agent and is a second- generation synthetic derivative of fluconazole; it is effective against yeast and filamentous fungi. The primary mode of action of voriconazole is the inhibition of cytochrome P-450- mediated 14-α-lanosterol demethylation, an essential step in fungal ergosterol biosynthesis and the resulting ergosterol depletion causes fungal cell wall destruction. It is well tolerated after oral administration; therapeutic aqueous and vitreous levels are achieved after administration of upto 200 mg twice a day.11,12

Reports of topical and oral voriconazole have illustrated its efficacy in the management of fungal keratitis caused by Candida, Fusarium, Alternaria, Scedosporium that was refractory to standard antifungal agents but responded to voriconazole treatment.11 It has also been effective for the treatment of Aspergillus fumigatus scleritis and epibulbar abscess resulting from scleral buckle infection.6 Intravitreal voriconazole has been used for drug-resistant fungal endophthalmitis.13 A recent report has compared the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of natamycin, amphotericin, and voriconazole against Aspergillus species isolated from keratitis.14 MIC of natamycin was 32 µg/ml, MIC of amphotericin B was 2-4 µg/ml, and that of voriconazole was the lowest 0.25-0.5 µg/ml. It is to be noted that effectiveness of antifungal agents depends on the concentration of drug achieved locally; in practice, the topical antifungals are given at different concentrations - amphotericin B because of toxicity is prescribed at 0.15%, voriconazole at 1% and natamycin at 5%; thus, although the MIC level of natamycin is higher, it is administered at five times the strength of voriconazole and 30 times that of amphotericin B. Thus, the natamycin MIC would need to be adjusted according to the available dose and will be lower.

Based on the available literature, eye drops were prepared by reconstituting lyophilized powder used for parenteral administration (Vfend 200 mg, Pfizer) with 19-ml sterile water for injection to obtain 20 ml of 1% solution and were administered every hour round the clock initially, they were then gradually tapered as the infection resolved over 2 months. The corneal infiltrate reduced remarkably in 2 weeks; however, the endothelial exudates and hypopyon took nearly 10 weeks to settle. Voriconazole eye drops were prepared every alternate day, stability of the solution could be extended up to 48 h between 2°C and 8°C, according to the manufacturer.11 Epithelial debridement may not be necessary for voriconazole penetration, because voriconazole is a small, lipophilic molecule.12 For optimum intraocular drug concentration, both oral and topical administration of voriconazole is recommended.12 Adverse effects of systemic use include visual disturbances such as enhanced light perception, color vision changes, visual blurring, skin rash, and hepatotoxicity, which are all transient in nature; on topical application, ocular burning has been reported. The duration of treatment depends on severity of keratitis and individual clinical response; it has been used for upto 4 months.6,11

Because of its broad spectrum of coverage, good tolerability, and excellent bioavailability with oral administration, voriconazole may be a good alternative against fungi-resistant to standard antifungal agents; however, the expenditure involved in voriconazole treatment will pose a constraint in its more frequent usage.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Camila Rodrigues, Microbiology Department, P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mahim, Mumbai, for laboratory diagnosis of fungal infection.

References

- 1.Sharma S, Srinivasan M, George C. The current status of Fusarium species in mycotic keratitis in South India. J Med Microbiol. 1993;11:140–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasan M. Fungal keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:321–7. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg P, Gopinathan U, Choudhary K, Rao GN. Keratomycosis: Clinical and microbiologic experience with dematiaceous fungi. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:574–80. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Vasu S, Meenakshi R, Palaniappan R. Epidemiological characteristics and laboratory diagnosis of fungal keratitis: A three-year study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51:315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Atmanathan S, Rao GN. The epidemiologic features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: A 10 year review at a referral eye care centre in South India. Cornea. 2002;21:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JE, Perkins SL, Harris GJ. Voriconazole treatment for fungal scleritis and epibulbar abcess resulting from scleral buckle infection. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:735–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denning DW, Ribaud P, Milpied N, Caillot D, Herbrecht R, Thiel E, et al. Efficacy and safety of voriconazole in the treatment of acute invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:563–71. doi: 10.1086/324620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis A, Sundmacher R, Tintelnot K, Agostini H, Jensen HE, Althaus C. Successful treatment of ocular invasive mold infection (fusariosis) with the new antifungal agent voriconazole. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:932–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.928d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariprasad SM, Meiler WF, Holz ER, Gao H, Kim JE, Chi J, et al. Determination of vitreous, aqueous and plasma concentration of orally administered voriconazole in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:42–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marangon FB, Miller D, Giaconi JA, Alfonso EC. In vitro investigation of voriconazole susceptibility for keratitis and endophthalmitis fungal pathogens. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:820–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunya VY, Hammersmith KM, Rapuano CJ, Brandon DA, Elisabeth JC. Topical and oral Voriconazole in the treatment of fungal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiel MA, Zinkernagel AS, Burhenne J, Kaufmann C, Haefeli WE. Voriconazole concentration in human aqueous humor and plasma during topical or combined topical and systemic administration for fungal keratitis. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2007;51:239–44. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00762-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen P, Gopal L, Sen PR. Intravitreal Voriconazole for drug resistant fungal endophthalmitis: Case series. Retina. 2006;26:935–9. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000250011.68532.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laitha P, Shapiro BL, Srinivasan M, Prajna NV, Acharya NR, Fothergill AW, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of fusarium, aspergillus and other filamentary fungi isolated from keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:789–93. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]