Abstract

Chronic suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis is an important cause of ocular surface discomfort. Treatment with topical antibiotics is often inadequate and surgical treatment by canaliculotomy and canalicular curettage has been the mainstay of treatment in the past. The role of canalicular antibiotic irrigation has been inadequately studied. We report the clinical features, microbiological profile and treatment outcome in a series of 12 patients with suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis. Two patients had Actinomyces infection, five had Nocardia infection and seven patients had polymicrobial infection. Three patients had resolution of canaliculitis on combination broad-spectrum topical antibiotic therapy using ciprofloxacin and fortified cefazolin. In nine patients, topical antibiotic therapy was combined with canalicular irrigation using fortified cefazolin. All patients had excellent resolution of canaliculitis without the need for surgical treatment. Availability of broad-spectrum antibiotics and canalicular irrigation may offer an alternative to surgery in the management of suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis.

Keywords: Canaliculitis, microbiological analysis, treatment

Canaliculitis, inflammation of the lacrimal canaliculi, results from suppurative infection or non-suppurative causes including a variety of viral infections,1,2 inflammatory conditions, following use of topical medications3 and following injuries.4 Suppurative canaliculitis is an important cause of recurrent conjunctivitis, epiphora and ocular surface discomfort.5-7 However, since it is uncommon, it may go unrecognized5,7 and is often misdiagnosed as chronic conjunctivitis or chalazion. Actinomyces8 (called ″streptothrix″ in early literature) and Nocardia9 are regarded as common organisms responsible for suppurative canaliculitis.

Conservative therapy is reported to be ineffective.5 Intracanalicular antibiotic irrigation has been reported,5 but has not been studied for its effectiveness. Previous studies have documented the effectiveness of canalicular curettage and/or canaliculotomy in the management of chronic canaliculitis,5,7,10 but these modalities have the potential to cause damage and scarring of the lacrimal drainage system. The role of topical antibiotics and canalicular irrigation with antibiotic solution has not been evaluated in detail.

We evaluated the clinical features, causative microorganisms, treatment and outcome of chronic suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis.

Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of all patients of lacrimal canaliculitis managed at Sankara Nethralaya, Chennai; during the period of January 1988 to May 2002. Only those patients with microbiologically proven chronic canaliculitis of more than three months duration and a minimum of three weeks post-treatment follow-up were included in this study. Expressed material from the canaliculus was collected with the help of cotton-tipped applicator in all the patients under aseptic precautions after instilling one drop of sterile 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride (Paracaine 0.5%, Sunways) or 4% lignocaine hydrochloride (lidocaine, Xylocaine 4%,Astra IDL) eye drop as a local anesthetic agent. The specimen was subjected to microbiological analysis and antibiotic sensitivity study. All patients were treated with canalicular expression of pus and topical antibiotic drops (fortified cefazolin 50 mg/ml + ciprofloxacin 0.3%) eight to ten times a day either alone or in combination with canalicular irrigation with two milliliters of fortified cefazolin solution (50 mg/ml).The line of treatment was decided by the clinical judgment of severity of the condition. The irrigation was repeated after 48 h if clinical improvement was not evident.

Fortified cefazolin solution (50 mg/ml) was prepared by injecting 10 ml of water for injection into the commercially available vial of cefazolin, containing 500 mg of the drug in powder form. The clinical outcome of various treatment modalities was analyzed.

Results

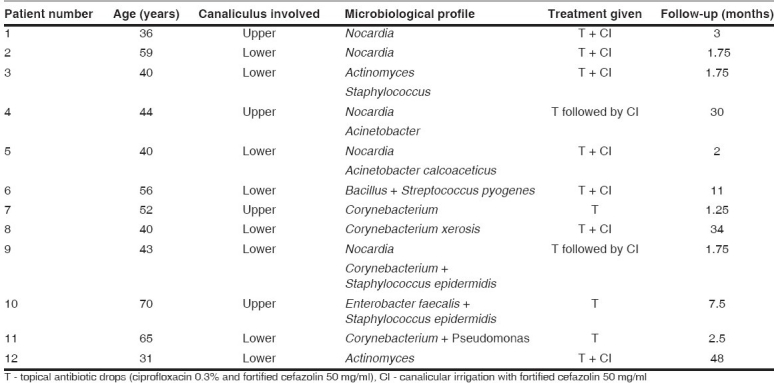

Patient details are summarized in the Table 1. All the patients had unilateral single canaliculus involvement. Lower canaliculus (eight out of 12) was more commonly involved than the upper canaliculus (four out of 12). Epiphora, discharge, irritation and recurrent or chronic conjunctivitis were the common symptoms. All patients had symptoms for more than three months duration (range: 3 to 24 months, mean:13.25 months). All patients had a pouting punctum and erythema as well as thickening of medial eyelid [Fig. 1]. Eight patients had punctal regurgitation, which could be induced by pressure over the involved canaliculus [Fig. 2]. Syringing was done in all patients through the involved canaliculus and was patent in all of them.

Table 1.

Patient profile, microbiological analysis and treatment of patients with suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis

Figure 1.

Slit-lamp photograph showing thickening of medial eyelid

Figure 2.

Slit-lamp photograph showing punctal regurgitation, induced by pressure over the involved canaliculus

In vitro resistance to ciprofloxacin was detected in two patients (Patient nos. 3 and 5). However, resistance to cefazolin was not detected in any of the patients.

Canalicular expression of pus and topical antibiotic drops alone was the initial treatment in five patients (Patient nos. 4, 7, 9, 10, 11) while canalicular expression, topical antibiotic drops and antibiotic irrigation was performed in the remaining seven patients.

Of the five patients treated with topical antibiotics alone, good clinical improvement was seen in three patients while in two patients (Patient nos. 4 and 9), the condition was persistent at the end of three weeks. Canalicular irrigation with fortified cefazolin was performed subsequently in these two patients with good response.

All patients who initially received canalicular antibiotic irrigation in addition to topical antibiotics showed good response to treatment. The average number of irrigations required per patient was 4.5 (range 1-8).

All patients were symptom-free with complete resolution and none needed canalicular curettage or canaliculotomy.

Discussion

Canaliculitis should be suspected in any patient with unexplained epiphora, recurrent conjunctivitis, eyelid swelling and pain. Pouting punctum, peripunctal erythema, thickening of medial eyelid and punctal regurgitation are the important signs of canaliculitis. Usually, it is localized to a single punctum, as in all the cases in our series.

In our study, polymicrobial infection was common in contrast to earlier studies, where Actinomyces or Nocardia was found to be the commonest organism.8,9 Since all the organisms isolated were sensitive to either cefazolin or ciprofloxacin or both, our patients were treated with canalicular expression and topical antibiotic (ciprofloxacin 0.3% and fortified cefazolin 50 mg/ml) with or without canalicular irrigation with fortified cefazolin solution.

Two of our patients did not respond to topical antibiotic alone. Polymicrobial infection including Nocardia was detected in both of them. These patients were subsequently treated successfully with antibiotic irrigation. Increased bioavailability of the drug at the site of infection may have been responsible for the excellent therapeutic response in this ″cross-over″ group. None of the patients treated with canalicular irrigation with antibiotic solution had any recurrence or persistence of the disease.

In our series, canalicular expression followed by topical antibiotic drops and canalicular irrigation with antibiotic solution according to the sensitivity pattern of the microorganism was found to be effective in all cases. Based on our study, we recommend use of fortified cefazolin, both in the form of topical eye drops and for syringing the affected canaliculus along with topical ciprofloxacin eye drops. This treatment has the advantage of eliminating the risk of iatrogenic canalicular scarring with preservation of lacrimal pump function. In the present age, due to availability of potent, bactericidal, broad- spectrum antibiotics like ciprofloxacin and cefazolin, invasive procedures like canalicular curettage and canaliculotomy may not be required. However, we feel a prospective study comparing these modalities of treatment will be needed to reassess the role of canalicular curettage and canaliculotomy in the management of suppurative lacrimal canaliculitis.

References

- 1.Harris GJ, Hyndiuk RA, Fox MJ, Taugher PJ. Herpetic canalicular obstruction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:282–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010284012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanke RF, Welham RA. Lacrimal canalicular obstruction following chickenpox. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:71–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee V, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Scalloping canaliculitis after 5-fluorouracil breast cancer chemotherapy. Eye. 1998;12:343–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumelt S, Remulla H, Rubin PA. Silicone punctal plug migration resulting in dacryocystitis and canaliculitis. Cornea. 1997;16:377–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199705000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vecsei VP, Huber-Spitzy V, Arocker-Mettinger E, Steinkogler FJ. Canaliculitis: Difficulties in diagnosis, differential diagnosis and comparison between conservative and surgical treatment. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208:314–7. doi: 10.1159/000310528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SmartPlug Study Group. Management of complications after insertion of SmartPlug punctual plug: A study of 28 patients. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1859. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavilack MA, Frueh BR. Thorough curettage in the treatment of chronic canaliculitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:200–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080140056026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards WW. Actinomycotic lacrimal canaliculitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:155–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)90669-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penikett EJ, Rees DL. Nocardia asteroides infection of the nasal lacrimal system. Am J Ophthalmol. 1962;53:1006–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz JJ. Canalicular diseases. In: Hurwitz JJ, editor. The lacrimal system. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 139–47. [Google Scholar]