Abstract

Objective

To study patterns and determinants of HIV prevalence and risk-behaviour characteristics in different population groups in four border provinces of Viet Nam.

Methods

We surveyed four population groups during April–June 2002. We used stratified random-cluster sampling and collected data concomitantly on HIV status and risk behaviours. The groups included were female sex workers (n = 2023), injecting drug users (n = 1391), unmarried males aged 15–24 years (n = 1885) and different categories of mobile groups (n = 1923).

Findings

We found marked geographical contrasts in HIV prevalence, particularly among female sex workers (range 0–24%). The HIV prevalence among injecting drug users varied at high levels in all provinces (range 4–36%), whereas lower prevalences were found among both unmarried young men (range 0–1.3%) and mobile groups (range 0–2.5%). All groups reported sex with female sex workers. Less than 40% of the female sex workers had used condoms consistently. The strongest determinants of HIV infection among female sex workers were inconsistent condom use (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 5.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.4–11.8), history of injecting drug use and mobility, and, among injecting drug users, sharing of injection equipment (adjusted OR, 7.3; 95% CI, 2.3–24.0) and sex with non-regular partners (adjusted OR 3.4; 95% CI 1.4–8.5).

Conclusion

The finding of marked geographical variation in HIV prevalence underscores the value of understanding local contexts in the prevention of HIV infection. Although lacking support from data from all provinces, there would appear to be a potential for sex work to drive a self-sustaining heterosexual epidemic. That the close links to serious injecting drug use epidemics can have an accelerating effect in increasing the spread of HIV merits further study.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier les schémas de contamination par le VIH, les déterminants de la prévalence du VIH et les caractéristiques des comportements à risque dans différents groupes de population vivant dans quatre provinces frontalières du Viet Nam.

Méthodes

Nous avons suivi ces quatre groupes de population sur la période avril-juin 2002. Nous avons obtenu par sondage en grappes un échantillon randomisé et stratifié et également recueilli sur la même période des données sur le statut VIH et les comportements à risque. Les groupes comprenaient des professionnelles du sexe (n = 2023), des utilisateurs de drogues injectables (n = 1391), des hommes célibataires de 15 à 24 ans (n = 1885) et différentes catégories de groupes mobiles (n = 1923).

Résultats

Nous avons constaté des variations géographiques marquées dans la prévalence du VIH, notamment pour les professionnelles du sexe (plage : 0 - 24%). La prévalence de ce virus chez les utilisateurs de drogues injectables était fortement variable dans les quatre provinces (plage : 4 - 36%) et se situait à un niveau plus bas à la fois chez les hommes jeunes et célibataires (plage : 0 – 1,3%) et les groupes mobiles (plage : 0 – 2,5%). Dans tous les groupes, des sujets ont rapporté avoir eu des rapports sexuels avec des professionnelles du sexe. Moins de 40% des professionnelles du sexe avaient utilisé systématiquement des préservatifs. Les plus forts déterminants de la contamination par le VIH de ces femmes étaient l’utilisation non systématique de préservatifs [odds ratio ajusté (OR) : 7,3 ; intervalle de confiance (IC) à 95% : 2,4 – 11,8], l’existence d’antécédents d’usage de drogues injectables et de mobilité, et parmi les utilisateurs de drogues injectables, le partage du matériel d’injection (odds ratio ajusté : 7,3, IC à 95% : 2,3 – 24,0) et les rapports avec des partenaires non réguliers (odds ratio ajusté : 3,4 ; IC à 95% : 1,4 – 8,5).

Conclusion

La variation géographique marquée de la prévalence du VIH relevée dans cette étude souligne l’intérêt de comprendre les contextes locaux dans la prévention de la contamination par ce virus. Malgré l’insuffisance des données à l’appui de cette hypothèse pour les quatre provinces, il semble qu’il existe un risque que le commerce du sexe entraîne une épidémie hétérosexuelle autoentretenue. La possibilité que les liens étroits entre les fortes épidémies de toxicomanie par des drogues injectables et l’épidémie de VIH puisse accélérer la propagation de ce virus mérite d’être étudiée de manière plus poussée.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estudiar la distribución y los determinantes de la prevalencia del VIH y las características de los comportamientos de riesgo en diferentes grupos de población de cuatro provincias fronterizas de Viet Nam.

Métodos

Encuestamos cuatro grupos de población entre abril y junio de 2002. Utilizamos un muestreo aleatorio y estratificado por conglomerados y recogimos simultáneamente datos sobre el estado serológico y los comportamientos de riesgo. Los grupos estudiados fueron trabajadoras del sexo (n = 2023), consumidores de drogas inyectables (n = 391), varones solteros de 15 a 24 años (n = 1885) y diferentes categorías de grupos móviles (n = 1923).

Resultados

La prevalencia del VIH presentó grandes variaciones geográficas, en particular entre las trabajadoras del sexo (0–24%). Su prevalencia presentó grandes variaciones en todas las provincias entre los consumidores de drogas intravenosas (4–36%), y fue menor en los jóvenes solteros (0–1,3%) y los grupos móviles (0–2,5%). Todos los grupos mencionaron tener relaciones con trabajadoras del sexo, entre las cuales el uso sistemático de preservativos fue inferior al 40%. Los principales determinantes de la infección por VIH entre las trabajadoras del sexo fueron el uso no sistemático de preservativos (razón de posibilidades [odds ratio: OR] ajustada: 5,3; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%]: 2,4 a 11,8), los antecedentes de consumo de drogas inyectables y la movilidad, mientras que entre los consumidores de drogas inyectables fueron el compartir el instrumental de inyección (OR ajustada: 7,3; IC95%: 2,3–24,0) y las relaciones sexuales con parejas no estables (OR ajustada: 3,4; IC95%: 1,4–8,5).

Conclusión

La gran variación geográfica de la prevalencia del VIH subraya la importancia del conocimiento de los contextos locales en la prevención de la infección. Aunque no todos los datos obtenidos en las diferentes provincias fueron en el mismo sentido, parece que el comercio sexual podría ser el determinante de una epidemia heterosexual autosostenida. Un tema que merece un estudio más profundo es que la estrecha relación con la grave epidemia de consumo de drogas inyectables pueda tener un efecto acelerador de la diseminación del VIH.

ملخص

الەدف

دراسة أنماط ومحددات انتشار فيروس الإيدز وخصائص السلوكيات المحفوفة بالمخاطر في فئات سكانية مختلفة في أربع مقاطعات تقع على الحدود في فييت نام.

الطريقة

قمنا خلال الفترة نيسان/إبريل – حزيران/يونيو 2002 بتقصي أربع فئات سكانية. وقمنا في ەذا المسح بأخذ العينات بالطريقة الطبقية التجمعية العشوائية، وقمنا بجمع البيانات بطريقة موازية عن وضع فيروس الإيدز والسلوكيات المحفوفة بالمخاطر. وشملت فئات الدراسة البغايا (عددەن 2023)، ومتعاطي المخدرات بالحَقْن (عددەم 1391)، والذكور غير المتزوجين في الفئة العمرية 15 – 24 عاماً (عددەم 1885)، وفئات مختلفة من المجموعات السكانية المتنقلة (عددەم 1923).

الموجودات

لوحظ تباين جغرافي واضح في معدل انتشار فيروس الإيدز، ولاسيما بين البغايا (تراوح من صفر إلى 24%). كما تفاوت معدل انتشار الفيروس بين متعاطي المخدرات بالحقن تفاوتاً كبيراً في جميع المقاطعات (من 4 إلى 36%)، في حين لوحظت معدلات انتشار أقل بين كل من الشباب الذكور غير المتزوجين (من صفر إلى 1.3%) والمجموعات السكانية المتنقلة (من صفر إلى 2.5%). وقد أبلغ المشاركون من جميع المجموعات عن مقارفتەم للعلاقات الجنسية مع البغايا. وبينت الدراسة أن أقل من 40% من البغايا يستخدمون العوازل بشكل منتظم. وكانت أقوى العوامل المحددة للإصابة بفيروس الإيدز بين البغايا ەي: عدم الانتظام في استخدام العوازل (نسبة الأرجحية المصحَّحة 5.3 عند فاصلة ثقة 95%، إذ تراوحت من 2.4 إلى 11.8)، وسوابق تعاطي المخدرات بالحقن، والتنقل. وكانت أقوى العوامل المحددة للإصابة بالفيروس بين متعاطي المخدرات بالحقن ەي التشارك في المحاقن (نسبة الأرجحية المصحَّحة 7.3، عند فاصلة ثقة 95%، إذ تراوحت من 2.3 إلى 24)، ومقارفة العلاقات الجنسية مع شريكات غير منتظمات (نسبة الأرجحية المصحَّحة 3.4، عند فاصلة ثقة 95%، إذ تراوحت من 1.4 إلى 8.5).

الاستنتاج

إن النتيجة المتمثلة في التباين الجغرافي الملحوظ في معدل انتشار العدوى بفيروس الإيدز، تؤكد على أەمية فەم السياق المحلي في الوقاية من فيروس الإيدز. ومن المحتمل أن تتسبب ممارسة البغاء في وباء قائم بذاتە ينتقل عن طريق العلاقة الجنسية، برغم الافتقار إلى ما يدعم ەذا الافتراض من واقع المعطيات الواردة من جميع المقاطعات. وقد تدعو الحاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسة حول تأثير وباء تعاطي المخدرات بالحقن على انتشار فيروس الإيدز.

Introduction

Many countries in Asia are experiencing epidemics of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in injecting drug users and female sex workers. These epidemics are characterized by a marked contrast in patterns of HIV transmission both within and between countries.1,2 The situation in the neighbouring countries of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Viet Nam provides a particular illustration of sharply contrasting epidemic patterns.3–6

In Viet Nam significant HIV epidemics have been observed among both injecting drug users and female sex workers.6 Among groups surveyed in the general population (antenatal clinic attendees, military recruits), HIV prevalence has been relatively low and below 1% in all places surveyed. In these groups, however, signs of a steady rise have been observed.6–8 This evidence is based primarily on data from urban populations; little is known about the situation in rural areas, where at least 70% of the population resides. Another observation from Viet Nam is that female sex workers and injecting drug users are sexually linked, with female sex workers reporting injecting drug use at significant levels in some areas.6–9

As part of the intervention project Community Action for Preventing HIV/AIDS in Cambodia, Viet Nam and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, baseline surveys were conducted in 2002 to provide a basis for short- and long-term evaluation.10 These surveys were designed to inform the process of interventions. The aim of this paper is to examine the baseline data from Viet Nam in this regard. We examine HIV risk distribution and determinants in different population subgroups assumed to be at higher risk of HIV infection compared with the general population.

Methods

We selected four border provinces for particular intervention support under the Community Action for Prevention of HIV/AIDS Project for the period 2002–2004.10 These included Lai Chau in the north and An Giang, Dong Thap and Kien Giang in the south. The surveys targeted four different population groups, i.e. female sex workers, injecting drug users, young unmarried men aged 15–24 years and groups assumed to be highly mobile, such as border traders and fishermen. We collected information about HIV status, demographic characteristics and risk behaviours. We administered a standard questionnaire during face-to-face interviews.

Sampling procedures

We used a two-stage cluster sampling strategy. Sites chosen for sampling were in the main cities and towns and districts in areas bordering another country.10

Street-based female sex workers: The total designated was 360 per province. In the first stage, we identified locations where street-based female sex workers were likely to be found. We randomly selected 36 locations using the probability proportional to size design method. From each location, we randomly selected 10 street-based female sex workers from all women present at the site at the time of the visit of the interviewing team.

Karaoke-based female sex workers: The total designated was 450 per province. We selected 150 sites using the probability proportional to size design method with a sampling frame that consisted of time–location clusters based on geographic sites, time of day and day of the week. We randomly selected three sex workers at each site.

Injecting drug users: We selected half of the designated sample (total 360) from the available list of those registered and the other half from mapped locations defined as locations where injecting drug users gather and could be accessed. From a sampling frame based on a list of district communes with registered injecting drug users, we randomly selected 15 injecting drug users. At each commune, we randomly selected 12 injecting drug users by choosing four primary respondents (index cases) from the list of registered injecting drug users. We then asked each primary respondent to lead the interviewer to two additional respondents using the “snowball technique”.

Young men: We designated a total of 480 to be sampled per province. In each commune, we randomly selected 10 households at different places as index households. For each selected household, we listed all the people aged 15–24 years and randomly selected one for participation in the survey. The interviewer continued visiting neighbouring households employing the random direction approach. The same procedure was used until we reached the total sample size.

Seafarers/sea fishermen: We designated a total of 480 to participate in Kien Giang province. The sampling frame consisted of all harbours and the estimated number of boats per harbour. We randomly selected 30 harbours; from each harbour, we randomly selected four boats and four people per boat.

Migrant construction workers: We carried out sampling only in Lai Chau province (480 designated). The sampling frame consisted of all houses listed under construction with an estimated measure of size. We used the probability-proportional-to-size design method to select 60 clusters and then selected eight respondents from each cluster.

Border traders: We sampled these in An Giang and Dong Thap. We identified all districts having local trade with Cambodia. We randomly selected traders from roads passing close to the border until we reached a sample size of 480.

Laboratory procedures

We employed the HIV testing strategy III (WHO), using Determine HIV1/2 (Abbott, Tokyo, Japan) as the first test. Non-reactive tests were considered HIV antibody-negative. We tested reactive samples again by Murex HIV1/2 (Abbott). For samples reactive in both tests, we used Genscreen HIV1/2 (Bio-Rad, Marne La Coquette, France) as the third test. Sera reactive in all three tests were considered HIV antibody-positive. For sera reactive in the first test but not in the second test, we repeated both tests. Indeterminate tests were those either remaining discordant in the second test or reactive in the first two tests but not in the third.

Data analysis

We analysed the data in Stata 8.0 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA). We analysed HIV prevalence, type of exposure and related consistent condom use by province and subpopulation group. In An Giang, the province with a high HIV prevalence in both injecting drug users and female sex workers, a logistic regression model was established and performed separately for the two groups. Included in this model were factors either identified through a review of the literature or found to be associated with HIV infection in the bivariate analysis. For both groups, we included the following variables in the model: age, marital status, educational attainment and knowledge of own HIV status. The variables added to the model for the injecting drug user data were type of sexual exposure (sex with female sex workers or other non-regular sex), history of sharing injection equipment and history of being in a drug rehabilitation programme. We were not able to include condom use as a variable in the analysis among injecting drug users, since information on condom use was collected separately by type of female sex worker. For the analysis of the female sex worker data, we included the following additional factors: category of sex worker, consistent condom use with one-time clients (i.e. always using condoms in the past month), history of injecting drug use, self-reported sexually transmitted infections during the past year, and mobility (having worked in other provinces). For injecting drug users, condom-use data were collected separately by type of female sex worker contact; condom use with one-time clients was used, as this was similar to that found in regular clients. The design effect of cluster sampling was taken into account in the logistic regression models. The indicator for condom use for groups other than female sex workers was “use last time sex”, since “always in the past month” gave unstable estimates due to small numbers.

Ethical aspects

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology in Hanoi, Viet Nam. We informed participants about the purpose of the survey, the interview and HIV testing and then asked them for personal consent before the interview and venesection. HIV test results were not linked to individuals, i.e. they were unlinked anonymous. Participants were not given any compensation for participating in the study.

Findings

Distribution of HIV

There were marked geographical contrasts in the HIV prevalence (Table 1). An Giang differed from the other provinces in terms of high HIV prevalence among both injecting drug users and female sex workers. We found high levels of HIV among injecting drug users in all of the four provinces surveyed (range 4–36%). Among female sex workers, the prevalence was relatively low (< 2%) in all provinces except An Giang, where the prevalence was 24.3% (95% CI, 16.1–32.3%) in street-based female sex workers and 16.5% (95% CI, 8.9–23.9%) in karaoke-based female sex workers. In both groups of female sex workers, the highest prevalence was found in the youngest age groups (Table 2). The prevalence was relatively low in the mobile groups, except border traders in An Giang (2.1%; 95% CI, 1.0–3.8%) and Dong Thap (2.5%; 95% CI, 1.3–4.3%). Among young men, the point prevalence was below 1% in all provinces except Lai Chau (1.3%; 95% CI, 0.5–2.7%).

Table 1. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence among the surveyed population groups.

| Population group | HIV prevalence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lai Chau | Kien Giang | Dong Thap | An Giang | |

| Street-based female sex workers | 1.9 (95% CIa 0.1–9.9) (54)b | 0.0 (216) | 1.5 (95% CI 0.3–4.3) (201) | 24.3 (95% CI 20.1–28.8) (400) |

| Karaoke-based female sex workers | 0.0 (49) | 1.3 (95% CI 0.5–2.9) (449) | 1.4 (95% CI 0.4–3.5) (291) | 16.5 (95% CI 12.9–20.8) (363) |

| Injecting drug users | 36.1 (95% CI 31.2–41.4) (359) | 23.5 (95% CI 19.4–28.0) (400) | 4.0 (95% CI 2.0–7.1) (274) | 13.4 (95% CI 10.1–17.4) (358) |

| Unmarried young men | 1.3 (95% CI 0.5–2.7) (480) | 0.4 (95% CI 0.1–1.6) (454) | 0.0 (481) | 0.6 (95% CI 0.1–1.9) (470) |

| Mobile groupsb | 0.0 (478) | 0.2 (95% CI 0.0–1.1) (485) | 2.5 (95% CI 1.3–4.3) (480) | 2.1 (95% CI 1.0–3.8) (480) |

a CI = confidence interval. b Figures in parentheses are the total sample size. c Mobile groups: Seafarers in Kien Giang, migrant construction workers in Lai Chau, and border traders in An Giang and Dong Thap.

Table 2. Age distribution of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence (%) in An Giang province (total number in brackets).

| Population group | Age group (years) |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 20–24 | 25–29 | ≥ 30 | |||

| Street-based female sex workers | 39.1 (95% CIa 27.3–50.9) (69)b | 35.4 (95% CI 27.2–44.4) (127) | 29.0 (95% CI 18.0–40.0) (69) | 3.7 (95% CI 0.1–6.9) (135) | 24.3 (95% CI 20.1–28.8) (400) | |

| Karaoke-based female sex workers | 26.8 (95% CI 16.2–37.3) (71) | 15.2 (95% CI 10.1–20.2) (198) | 11.7 (95% CI 3.3–20.0) (60) | 11.8 (95% CI 0.1–23.1) (34) | 16.5 (95% CI 12.9–20.8) (363) | |

| Injecting drug users | 17.1 (41) 95% CI (7.1–32.1) | 18.6 (113) 95% CI (11.9–27.9) | 15.7 (51) 95% CI (7.0–28.6) | 7.8 (153) 95% CI (4.1–13.3) | 13.4 (358) 95% CI (10.1–17.4) | |

| Unmarried young men | 0.0 (251) | 1.4 (95% CI 0.3–3.9) (219) | No data | No data | 0.6 (95% CI 0.1–1.9) (470) | |

| Mobile groups | 2.9 (95% CI 0.3–9.9) (70) | 1.6 (95% CI 0.2–5.5) (128) | 4.9 (95% CI 1.3–12.0) (82) | 1.0 (95% CI 0.1–3.6) (200) | 2.1 (95% CI 1.0–3.8) (480) | |

a CI = confidence interval.

Distribution of risk behaviour and links between population groups

Injecting drug users were consistently (across provinces) linked sexually with both female sex workers and other non-regular sexual partners (data not shown). The proportion of “last time sex condom use” was less than 60% and lowest in An Giang province (38%). A consistent finding regarding condom use in female sex workers was the particularly low use with husbands and boyfriends. Among mobile groups, female sex workers were the most frequent non-regular sex partners. Regardless of the mobile group category, consistent condom use with female sex workers was high but significantly lower with other non-regular partners and particularly low with regular partners. Among young men, sexual contacts were most frequent with a regular partner; links to non-regular partners were limited, except in two provinces, where contacts with female sex workers were significant (8% in An Giang and 9% in Kien Giang).

Injecting drug use among female sex workers was highest (6%) in An Giang province, 4% in Lai Chau and less than 1% in the other provinces (data not shown). Mobility (i.e. female sex workers also working in other provinces) did not differ significantly across provinces (range 15–21%; data not shown). Among young men, less than 1% reported ever having injected drugs (data not shown).

The use of public sexually transmitted infection clinics was very low for all groups. Overall, 9.9% of female sex workers reported a sexually transmitted infection in the past 12 months; of these, 14.5% sought treatment in the public sector and 67.6% in a private clinic (data not shown).

Factors associated with HIV infection among high-prevalence groups

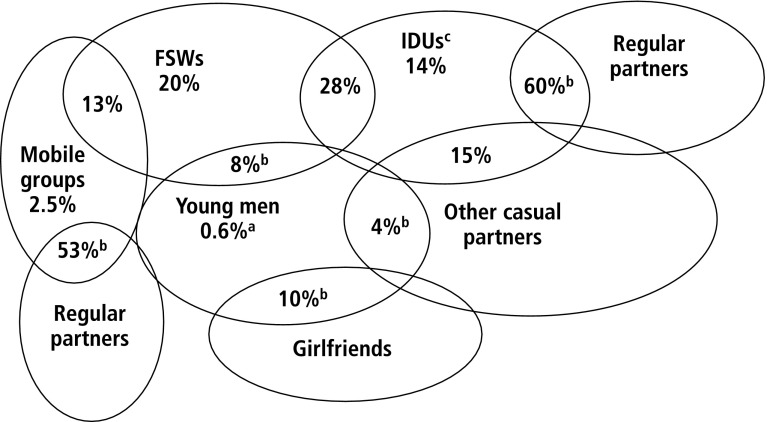

Fig. 1 summarizes sexual links between the various risk groups in An Giang, where HIV prevalence was very high among both female sex workers and injecting drug users. Among female sex workers, the strongest associations were irregular condom use, injecting drug use and mobility (data not shown). Ever having injected drugs was reported by 6% of the respondents; the likelihood of HIV infection was 7.8 times higher in these respondents compared with respondents who had never injected. Consistent condom use with one-time clients during the past month was reported by 31% of female sex workers. The estimated likelihood of HIV infection among those who used irregular protection was 5.3 times that of those who consistently used condom (data not shown). Mobility, defined as having worked in other provinces, and reported by 15%, was estimated to increase the likelihood of HIV threefold compared with non-mobile women. In the 13% of mobile women who reported having worked abroad, the HIV prevalence was 73% (data not shown). Knowledge of own HIV status, reported by 12% (18% ever tested), tended to reduce the likelihood of HIV infection (statistically significant when adjusted for age, but not in the full model). Educational attainment did not appear to be associated with HIV status (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Sexual networks linking sub-epidemics in An Giang

a Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

b Sexual contacts measured as percentage with one or more sexual contacts during the past 30 days.

c IDUs = injecting drug users.

d FSWs = female sex workers.

Prominent risk factors among injecting drug users were related to sharing of injection equipment and sexual linkages with female sex workers and other non-regular partners (data not shown). Sharing injecting equipment was reported by 5% of the respondents, and the estimated odds in favour of HIV infection was 7.3 times that of the group that had not shared. Sexual relationships with both female sex workers and other non-regular partners (reported by 12%) appeared to increase the likelihood of infection 3.4 times compared with injecting drug users reporting no non-regular sexual contacts. The likelihood of infection was more than three times higher among those being aware of their own HIV status (reported by 7%) versus not knowing, contrasting with the negative association in female sex workers (data not shown). Finally, being married was found to play a strong protective role, with odds in favour of infection about five times greater in those unmarried, while those with higher educational attainment tended to be more likely to be infected with HIV.

Discussion

We found striking geographical differences in HIV prevalence between the groups studied. This is in agreement with the observations from the national HIV sentinel surveillance system, showing that HIV epidemics started at different times and developed at different rates in injecting drug users and female sex workers.6–8 Several observations were indicative of close links between drug-injection-related and heterosexual epidemics. First, a substantial proportion of injecting drug users in all provinces reported recent sexual relationships with female sex workers (average, 21%; range, 9–34%) and with other non-regular and regular partners. Second, in An Giang, the only province with high HIV rates among female sex workers, sex with female sex workers and other non-regular sex partners appeared to be associated strongly with HIV infection among injecting drug users. Third, a notable proportion of men in mobile occupations reported sex with female sex workers during the past 30 days, whereas among young men these links were less frequent. Finally, consistent condom use was low in all groups, e.g. less than 40% of female sex workers had always used condoms with clients in the past 30 days.

Several possible limitations are involved in this baseline assessment. In several of the provinces, the total number of subjects sampled, particularly female sex workers, was low, thereby making estimates less precise and with some overlap in confidence intervals. Furthermore, the precision was also low for estimates of condom use among young men and mobile groups. The reason for this was that reported sexual contacts and related use of condoms covered a short timeframe (the past month), leading to low proportions reporting sexual contacts and thus low number of respondents. Studies suggest that underreporting the number of lifetime sexual partners is common.11 This is likely to apply to culturally inappropriate sexual behaviour, which is associated with stigmatization, thereby creating a social desirability-related reporting bias. Analyses of associations with and changes in self-reported sexual behaviour should therefore be interpreted with caution. The potential problem of non-response in our study was not likely to significantly bias results as it was very low in all the groups sampled.

The situation in An Giang province, a border area adjacent to Cambodia, appears to differ from the other provinces in several ways. First, the HIV prevalence among female sex workers has been high over a long period. A survey conducted in 1995 found that 9.5% of the sampled sex workers were infected with HIV; mobility of the women and prostitution across the border was suggested as the most likely explanation for such a high prevalence at that time.12 Second, the epidemic among sex workers appears to have been established before the start of the injecting drug use epidemic. This is evidenced from HIV surveillance findings among injecting drug users in An Giang since 1994 showing very low HIV prevalence (< 1%) in 1994 and 1995.8 The comparison with the 1995 survey indicates that condom use has remained low, sharply contrasting the favourable changes observed among female sex workers in neighbouring Cambodia.3,4 Our finding of a strong independent association between “sex with non-regular partners” and HIV infection among injecting drug users suggests that sexual transmission has been an important factor in fuelling the epidemic in this group, i.e. there is a reciprocal relationship.

It is recognized widely that HIV epidemics among injecting drug users can contribute to more generalized HIV epidemics in many settings.13 However, the effects of interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviour among injecting drug users have generally been modest.14 The degree to which epidemics among injecting drug users can contribute has been examined using different approaches, including mathematical modelling of HIV transmission.15–17 Saidel et al. explored scenarios for potential HIV transmission from injecting drug users to non-injecting sexual partners and beyond. Their model was applied to what was called a “general Asian” setting, i.e. assuming that (i) there is the potential for sex work to drive a self-sustaining heterosexual epidemic and (ii) most injecting drug users are males not involved in sex work but a substantial minority of them are clients of female sex workers.16 The model indicated that a large acceleration effect can exist between injecting drug users and female sex workers, particularly when assuming high levels of HIV among injecting drug users and still low levels among female sex workers.17 There was no evidence in our data of such a large acceleration effect. Despite very high prevalences among injecting drug users, the HIV prevalence among female sex workers was still relatively low in all provinces, except An Giang, where substantial transmission among injecting drug users started at a much later stage than among female sex workers. It should be noted that the work of Saidel et al. did not include the possible effect of injecting drug users who are sex workers.17 Injecting drug use among female sex workers has been reported to be high in major cities, particularly in street-based female sex workers (e.g. Hanoi, 22%), but to be at low levels in most other areas.9,18–20 In our survey, the proportion of female sex workers having ever injected drugs was low (range < 1–6%). However, a history of drug injection and HIV infection was associated strongly, suggesting that drug-injecting female sex workers do have a high potential to accelerate heterosexual HIV epidemics.

Few studies from Viet Nam have documented current sexual behaviour and existing networks of sexual mixing of males. The behaviour surveillance system covered long-distance workers and migrant workers, and the findings correspond well with what we found among mobile groups in terms of proportions having sex with female sex workers.9 We have documented that in most places a substantial proportion of young unmarried men have multiple sex partners and low levels of consistent condom use. However, documentation of risk behaviours among adult men is still limited.

The association between “knowing own HIV status” and HIV infection was found to be negative among female sex workers but strongly positive among injecting drug users. This difference is puzzling. Access to voluntary HIV counselling and testing was insignificant in the project communities at the time of survey. In the present regression model, the association might be related to both the actual knowledge of HIV status and the “characteristic of knowing” itself. The latter has been found to be the case in the sense that HIV-infected individuals who perceive deteriorating health tend to be more likely to seek HIV testing, leading to a positive association between HIV and knowledge of HIV.21

This project includes actions on several fronts, including behaviour-change communication, condom promotion and targeted sexually transmitted infection services. Our findings suggest that injecting drug users and female sex workers are the most important groups to reach in terms of prevention. In neighbouring Cambodia, prevention efforts related to sex work have generally been regarded as successful.3,4 These efforts have been centred around a 100% condom use approach that also includes comprehensive sexually transmitted infection interventions. The low levels of condom use and high levels of gonorrhoea and chlamydia recently identified in the project provinces support the potential of this strategy.22 The findings also support giving high priority to harm-reduction programmes, including peer education, voluntary HIV counselling and testing, and needle and syringe exchange. Careful monitoring of outputs of such interventions in terms of coverage, intensity, acceptability and quality will be critical to inform process. ■

Acknowledgements

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) financed the study through the Japan Community Action for Preventing HIV/AIDS Project. The authors thank all the staff at the Preventive Medicine Centers of Lai Chau, An Giang, Kien Giang and Dong Thap, other staff that participated in the survey and Peter Godwin of ADB.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.Walker N, Stanecki KA, Brown T, Stover J, Lazzari S, Garcia-Calleja JM, et al. Methods and procedures for estimating HIV/AIDS and its impact: the UNAIDS/WHO estimates for the end of 2001. AIDS. 2003;17:2215–25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. WHO. AIDS epidemic update: December 2005. Geneva, UNAIDS 2003.http://www.unaids.org/en/Resources/Publications/Corporate+ publications/AIDS+epidemic+update+-+December+2003.asp

- 3.Saphonn V, Sopheab H, Penhsun L, Vun NC, Wantha SS, Gorbach PM, et al. Current HIV/AIDS/STI epidemic: intervention programs in Cambodia, 1993–2003. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:64–77. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.64.35522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sopheab H, Fylkesnes K, Vun MC, O’Farrell N. HIV-related risk behaviours in Cambodia and effects of mobility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:81–6. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174654.25535.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV surveillance survey and sexually transmitted infection periodic prevalence survey. Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Survey report, 2001.

- 6.Ministry of Health of Viet Nam. Current status of the HIV&AIDS epidemic in Vietnam December 2002. Review and analysis on data from HIV/AIDS surveillance systems and research studies. Draft report.

- 7.Quan VM, Chung A, Long HT, Dondero TJ. HIV in Vietnam: the evolving epidemic and the prevention response, 1996 through 1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:360–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen TH, Hoang TL, Pham KC, van Ameijden EJ, Deville W, Wolffers I. HIV monitoring in Vietnam: system, methodology and results of sentinel surveillance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:338–46. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199908010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS behavioral surveillance survey, Vietnam 2000. Results, Hanoi: National AIDS Standing Bureau, Family Health International, 2001.

- 10.Asian Development Bank. Community action for preventing HIV/AIDS. Proposed grant assistance. Financed from the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction, to Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. JFPR: Reg 9006, April 2001.

- 11.Buve A, Lagarde E, Carael M, Rutenberg N, Ferry B, Glynn JR, et al. Interpreting sexual behaviour data: validity issues in the multicentre study on factors determining the differential spread of HIV in four African cities. AIDS. 2001;15:S117–26. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thuy NTT, Nhung VT, Thuc NV, Lien TX, Khiem HB. HIV infection and risk factors among female sex workers in southern Vietnam. AIDS. 1998;12:425–32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199804000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strathdee SA. Sexual HIV transmission in the context of injection drug use: implications for interventions. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:79–81. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00211-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanichseni S, Des Jarlais DC, Choopanya K, Mock PA, Kitayaporn D, Sangkhum U, et al. Sexual risk reduction in a cohort of injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1170–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000120821.38576.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowndes CM, Renton A, Alary M, Rhodes T, Garnett G, Stimson G. Conditions for widespread heterosexual spread of HIV in the Russian Federation: implications for research, monitoring and prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:45–62. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00208-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassly NC, Lowndes CM, Rhodes T, Judd A, Renton A, Garnett GP. Modelling emerging HIV epidemics: the role of injecting drug use and sexual transmission in the Russian Federation, China and India. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:25–43. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00224-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saidel TJ, Jarlais DD, Peerapatanapokin W, Dorabjee J, Singh S, Brown T. Potential impact of HIV among IDUs on heterosexual transmission in Asian settings: scenarios from the Asian Epidemic Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00209-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hien NT, Giang LT, Binh PN, Deville W, van Ameijden EJ, Wolffers I. Risk factors of HIV infection and needle sharing among injecting drug users in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:45–58. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TA, Hoang LT, Pham VQ, Detels R. Risk factors for HIV-1 seropositivity in drug users under 30 years old in Haiphong, Vietnam. Addiction. 2001;96:405–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen AT, Nguyen TH, Pham KC, Le TG, Bui DT, Hoang TL, et al. Intravenous drug use among street-based sex workers: a high-risk behaviour for HIV transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:15–9. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000105002.34902.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fylkesnes K, Siziya S. A randomised trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counselling and testing. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:566–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen VT, Nguyen TL, Nguyen DH, Le TT, Vo TT, Cao TB, et al. Sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in five border provinces of Vietnam. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:550–5. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175415.06716.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]