Abstract

Health has gained recognition as a foreign policy concern in recent years. Political leaders increasingly address global health problems within their international relations agendas. The confluence of health and foreign policy has opened these issues to analysis that helps clarify the tenets and determinants of this linkage, offering a new framework for international health policy. Yet as health remains profoundly bound to altruistic values, caution is required before generalizing about the positive outcomes of merging international health and foreign policy principles. In particular, the possible side-effects of this framework deserve further consideration.

This paper examines the interaction of health and foreign policy in humanitarian action, where public health and foreign policy are often in direct conflict. Using a case-based approach, this analysis shows that health and foreign policy need not be at odds in this context, although there are situations where altruistic and interest-based values compete. The hierarchy of foreign policy functions must be challenged to avoid misuse of national authority where health interventions do not coincide with national security and domestic interests.

Résumé

Ces dernières années, la santé en est venue à occuper une place plus importante en matière de politique étrangère et les responsables des relations extérieures sont appelés de plus en plus à aborder des problèmes de santé mondiale dans le cadre de leurs activités. Du fait de la confluence de la politique étrangère et de la politique de santé, ces problèmes ont donné lieu à des analyses qui contribuent à préciser les principes et les déterminants de cette corrélation, offrant ainsi un nouveau cadre à la politique sanitaire internationale. La santé restant intimement liée à des valeurs altruistes, il faut toutefois se montrer prudent et éviter les généralisations abusives quant aux effets positifs d’une fusion des principes régissant la politique sanitaire internationale et la politique étrangère. En particulier, la question des effets secondaires éventuels d’un tel cadre mérite une étude plus approfondie.

L’article examine l’interaction entre politique sanitaire et politique étrangère dans l’action humanitaire, où il y a souvent conflit direct entre les impératifs de santé publique et de politique étrangère. Avec une méthode fondée sur des cas pratiques, l’analyse montre que l’opposition n’est pas inévitable, même s’il arrive parfois que des intérêts concrets ne puissent s’accommoder de certaines valeurs altruistes. Il faut remettre en cause la hiérarchie des fonctions de politique étrangère pour éviter l’abus d’autorité au niveau national lorsque des interventions sanitaires ne cadrent pas avec la sécurité et les intérêts nationaux.

Resumen

En los últimos años se ha registrado un creciente reconocimiento de la salud como una importante faceta de la política exterior. Los líderes políticos abordan cada vez más problemas sanitarios mundiales en sus agendas de relaciones internacionales. La confluencia de la salud y la política exterior ha hecho que esas cuestiones se sometieran a análisis que ayudan a aclarar los principios y los factores determinantes de ese nexo, brindando un nuevo marco para la política sanitaria internacional. Sin embargo, puesto que la salud sigue profundamente vinculada a valores altruistas, se impone la prudencia antes de generalizar acerca de los resultados positivos de la fusión de la salud internacional y los principios de política exterior. En particular, los posibles efectos colaterales de este marco merecen ser considerados con más detenimiento.

En el presente artículo se examina la interacción de la salud y la política exterior en la acción humanitaria, donde la salud pública y la política exterior entran a menudo en conflicto directo. Utilizando un enfoque basado en casos, el análisis realizado muestra que la salud y la política exterior no tienen por qué estar reñidas en esas circunstancias, aunque hay situaciones en que los valores altruistas y los basados en intereses compiten entre sí. Es necesario cuestionar la jerarquía de las funciones de política exterior para evitar que se haga un uso indebido de la autoridad nacional cuando las intervenciones de salud no coincidan con los intereses y la seguridad nacionales.

ملخص

اكتسبت الصحة الاعتراف بەا كأحد قضايا السياسة الخارجية في السنوات الأخيرة، ويعالج القادة السياسيون المشكلات الصحية العالمية ضمن جداول الأعمال الخاصة بالعلاقات الدولية، وقد فتح الترابط بين الصحة والسياسة الخارجية باب ەذە المشكلات على مصراعيە للتحليل، مما ساعد في توضيح التحدِّيات والمحتِّمات لەذە الروابط، ومقدماً بذلك إطاراً جديداً للسياسة الصحية الدولية. ورغم أن الصحة لاتزال حتى يومنا ەذا عميقة الارتباط بقيم الإيثار، فلابد من الحذر قبل تعميم النتائج الإيجابية لإدماج الصحة الدولية ومبادئ السياسة الدولية، وتستحق التأثيرات الجانبية لەذا الإطار بشكل خاص المزيد من الاەتمام. وتدرس ەذە الورقة التفاعل المتبادل للصحة وللسياسة الخارجية مع الأعمال الإنسانية، حيث تتعارض الصحة العمومية مع السياسة الخارجية بشكل مباشر في غالب الأحيان، وقد استخدمنا في الدراسة أسلوباً يستند على الحالات، وأوضحت الدراسة أن الصحة والسياسة الخارجية قد لا يتعارضان في ەذا السياق، رغم وجود حالات تتنافس فيەا القيم المستندة على المنافع مع تلك التي تستند على الإيثار. إن البنية الەرمية لوظائف السياسة الخارجية يجب أن تجابە بتحدِّيات لتجنب سوء استخدام السلطات الوطنية، وذلك في المواقع التي لا تتوافق فيەا التدخلات الصحية مع الأمن الوطني والمنافع الوطنية.

Introduction

The linkages between health and the global policy agenda are well established.1–5 Examples include global efforts to control communicable diseases such as avian flu, human immunodeficiency virus/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and poliomyelitis; the pre-eminence of health among the Millennium Development Goals; health trade and financing issues; and international law’s growing recognition of these concerns through endorsement of the International Health Regulations. All of these cases reflect the increasing focuses of relationship, discussion and negotiation of health matters between countries.

In recent years, normative work has decrypted this multifaceted relationship between health and foreign policies. Pannisset conceptualizes the relationship between international health and international relations on the premise that both “result from dynamic social, cultural, economic and political interactions among different populations”.1 Fidler2,3 builds on the hierarchical order of foreign policy functions ranging from human dignity and development to economic and national security, and discusses how each relates to health. Specifically, he proposes various interpretations of the emergency of health concerns along that spectrum of functions from “hard power” to “soft power”.6 A mutually stimulating relationship — which at times is misconstrued as mutually beneficial — between health and foreign policy has been widely observed. However, the concept of health’s emergence in foreign policy circles is difficult to reconcile with empirical cases that reveal deep silences with respect to important components of international health principles.7 Different approaches and cases are needed to test the validity and strength of health and foreign policy linkages before generalizing about a mutually beneficial merger. The specific case of how health and humanitarian action cooperate with foreign policies promoting a peace settlement provides good conditions for such a test.

This paper uses a case-based Socratic argument to demonstrate that no matter how health is disguised in political terms, it will never uproot itself from its fundamentally altruistic, people-centred identity. And while this is often attempted, any generalization of the health and foreign policy concept that does not adopt an altruistically inspired framework is bound to either translate into wishful statements or lead to an unequal weighting of health issues according to the predominant hierarchy of foreign policy functions. Re-conceptualizing health and foreign policy mitigates these risks.

After outlining concepts and definitions and setting the scope and functions of humanitarian action, this paper will use examples to analyse how health and foreign policy can support such action. It will be clear that these differentially powered interactions point to an antagonistic relationship between health and foreign policy in the context of humanitarian crises. This antagonism calls for caution in applying the health and foreign policy nexus beyond the realm of national interest.

Concepts and definitions

Social sciences teach that humanitarian (altruistic) and political (interest-based) actions stem from a common root — an act of giving — but have evolved in opposite directions. Sociologist Marcel Mauss(1925)8 in France and anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1922)9 in the United Kingdom established that in archaic societies an act of giving was a means to build ties between two groups of people: a donor group and a recipient group. The former gives, the latter returns the gift, so both receive. The act of giving in these societies is a mechanism of permanent exchange of goods necessary for a group to govern relationships with another group, and thus a way for archaic societies to maintain control over each other. In this respect, it can be seen as a remote ancestor of foreign policy, a way to solicit mutual interests between two groups of people or societies.

In today’s world, acts of giving such as humanitarian action are no longer necessary to establish the structures and social fabric of societies. Rather, these acts of giving are confined to the very restricted but no less critical realm of the moral imperative to do good.10 A hierarchical set of roles and responsibilities — beyond the simple exchange of goods across territories — is required to govern relationships between countries. In other words, the act of giving, transposed to modern times and exemplified by humanitarian action, has long escaped from the foreign policy arena. The altruistic, people-centred value of humanitarian action is in intrinsic opposition to foreign policy’s interest-based, country-centric values.

This social concept requires some nuance, as the opposition does not imply that foreign policy cannot be humanitarian or vice versa. Humanitarian arguments often guide foreign policy decisions, but they are often regarded as a means to enhance reciprocity and national image. Humanitarian justifications are no longer altruistic then, but become interest-based and political.

Foreign policies are domestically defined and are implemented by the country. They abide by national interest in the sense of its pre-eminence over — and not exclusion from — the interests of the population. Conversely, humanitarian values are universally defined and agreed upon, and reflect broader interests than those of any country or population group. These values leave little room for compromise when they compete with domestic or national interests. This does not mean that altruistic values do not have political consequences. The intention here is to unveil and highlight these altruistic values so they are not overlooked by those who argue “everything is political”.

Functions and principles of humanitarian action

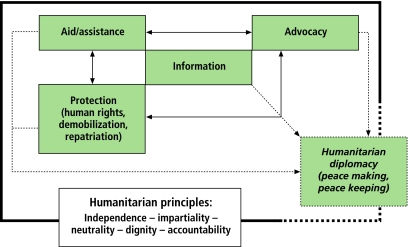

Humanitarian action is complex and multidimensional (Fig. 1). It conducts programmatic activities such as protecting civilians affected by disasters, repatriating refugees, exchanging prisoners of war, demobilizing combatants and providing vital assistance such as food, water, sanitation, shelter, health services and advocacy for people subject to all sorts of distress, including political, physical, sexual, psychological and economic harms.

Fig. 1.

Humanitarian action and embedded principles

Assistance, protection of rights and advocacy are core humanitarian functions. Their objectives are to save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity, hence creating the basic conditions for peace. These functions rely on the collection and analysis of data, making information-gathering a humanitarian function as well. These functions feed diplomatic efforts to reach peace settlements. Humanitarian diplomacy is thus a natural extension of humanitarian action, but it does not confer upon these humanitarian actors the legitimate authority to bring about peace. At most, they can play a significant role in triggering dialogue among conflicting parties.11 Ultimately, the success of a peace process depends on political commitment rather than humanitarian efficacy.

Moral imperatives and principles encapsulate humanitarian functions. The Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and Nongovernmental Organizations in Disaster Relief12 and the SPHERE Project’s Humanitarian Charter13 best summarize the guiding principles of humanitarian action. Inspired by international human rights and humanitarian law, these texts establish the pre-eminence of a humanitarian imperative that couples “the right to receive humanitarian assistance and to offer it for and by all citizens of all countries” with the obligation to provide aid and protection wherever and whenever needed. These documents insist on the non-partisan and altruistic nature of humanitarian action, which must remain strictly need-based and reflect the principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence. Humanitarian response “shall endeavour not to act as an instrument of foreign government policy” and is accountable to both those who seek to assist and those who accept resources. These instruments, developed to guide nongovernmental humanitarian action, are also useful benchmarks for bilateral and multilateral aid. While nongovernmental action operates with fewer political concerns, governmental aid often needs to refer to these principles to counter political obstacles. Governmental and intergovernmental humanitarian assistance remains largely subject to considerations of national interest, such as public opinion pressures and budgetary constraints.14

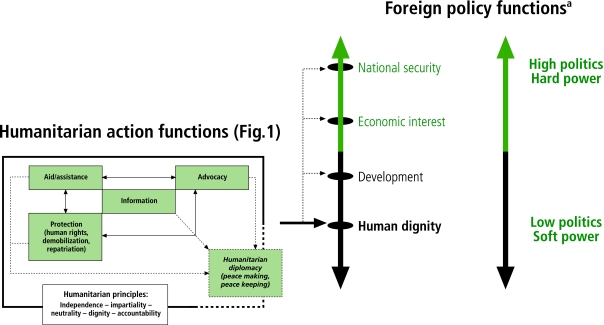

The precedence of the humanitarian altruistic imperative over self-serving politics keeps humanitarian action within the framework of soft-power foreign policy (Fig. 2). The past 15 years have seen efforts to develop a coherent agenda uniting humanitarian and political actions.

Fig. 2.

Humanitarian and foreign policy functions

a Adapted from Fidler.2

A marriage of convenience

Médecins sans Frontières told the Nobel Committee “Humanitarian action is an act of indignation, a refusal to accept an active or passive assault on the other.”15 This echoes social theory highlighting the altruistic nature of humanitarian action as a true act of giving. Yet in practice, both unofficial and government actors recognize that humanitarian action, mixed as it is with politics, does have political consequences.

During the conflict in the former Yugoslavia, most European countries formulated their Balkan policies in humanitarian terms, such as the need to establish protected humanitarian corridors and safety zones. These measures could in the short term allow massive numbers of people to escape violence. In the long run, the consequences were tragic on both political and humanitarian sides: humanitarian evacuation fed mass deportation and consequently “ethnic cleansing”,16 and safety zones fuelled the illusion of protection which in the case of Srebrenica led to massacre.17 More than a decade later, Bosnia and Herzegovina mirrors the ethno-political divisions they embodied at the war’s end.18 The case of the former Yugoslavia (similar to the contemporary cases of Somalia and Africa’s Great Lakes) confirmed how politics and humanitarian action can be mutually damaging when the latter is taken as a substitute for the former.

These failures signalled the need to rethink ways for humanitarian and political action to work together. A “new humanitarianism” became the modus operandi of a “policy of coherence” aiming to reinvigorate humanitarian action at government and international levels.19 This effort sought commonalities between humanitarian action and military, peace-building and nation-building interventions. To accommodate this approach, institutions have changed both at national and international levels. Special offices for foreign disaster management were established within foreign affairs ministries, with mandates similar to that of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.19 At both levels, the intention was to harmonize humanitarian responses to conflict with political and peace-building operations.

The “new humanitarianism” sought to link humanitarian and political action under the umbrella of foreign policy, but predictably it did not work out in reality the way it was proposed on paper. To make “coherence” work, the makers of foreign policy had to reaffirm their commitment to the basic humanitarian principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence, and to comply with the 23 Principles and Good Practices of Humanitarian Donorship.20,21 In foreign policy terms, this meant compromises with national interests. Instead, especially in non-strategic areas, donor governments gradually disengaged from political duties, leaving their humanitarian branches with impossible conflict management agendas. The “policy of coherence” implemented in Afghanistan and Sudan, although based on analyses of the early 1990s’ humanitarian tragedies, reconfirmed the difficulties involved in associating humanitarian and political actions.

Health and foreign policy hand in hand?

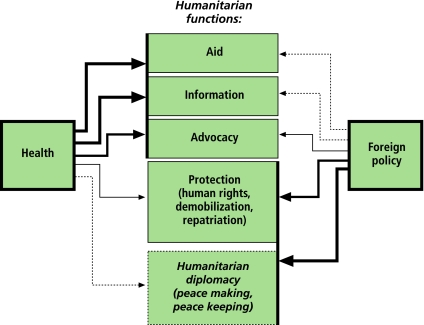

Health is a prominent consideration in humanitarian action but has varying importance across humanitarian functions. Although central in humanitarian aid and broadly used as a benchmark for good humanitarian practice overall, health plays a lesser role in humanitarian areas that are more closely linked with foreign policy (protection, demobilization, repatriation, humanitarian diplomacy). In fact, health tends to score highly in humanitarian practice where foreign policy cannot and vice versa, as Fig. 3 and the following examples may clarify.

Fig. 3.

Respective contribution and weighta of health and foreign policy on core humanitarian functions

a The width of the arrows indicates the strength of the relationship.

Humanitarian aid

Health and its associated disciplines of nutrition, water and sanitation are the gist of humanitarian aid because they respond to vital human needs. These sectors are the most frequently budgeted aid activities implemented in the aftermath of and recovery from disasters.22

When delivered in the name of (or as an alternative to) political efforts, aid can be harmful. In 1994, in the former Democratic Republic of the Congo, a government agency made large quantities of ciprofloxacin, an expensive second-line treatment for dysentery, available to Rwandan refugees. The use of that powerful antibiotic encouraged germ resistance to nalidixic acid, the only affordable therapy for dysentery, along the Rwandan border. Infected patients thus became dependent on drugs they could not afford. Such imposed assistance often offers inappropriate results with regard to needs, and is for this reason termed the “second disaster.”

Performance monitoring and advocacy

Health statistics inform crisis management, attest to humanitarian performance and feed advocacy. Both political and technical messages are sent by death tolls or rates; by numbers of missing, displaced and injured; and by statistics showing relative access to health services, food and safe water. Despite the difficulties of collecting data in disaster areas, the emerging practice of conflict epidemiology offers effective measurement methods that can generate reliable numbers to guide strategic decisions and influence political leaders.23

In 2004, Physicians for Human Rights, a nongovernmental organization based in the United States, conducted health and examination interviews among Sudanese refugees from Darfur in Chad. These experts established patterns of events tantamount to war crimes,24 and the interviews marked the first time epidemiology was used to “diagnose genocide”.25 A government-led investigation26 followed and led the United States to change its foreign policy in the region.27 By terming the conflict genocide, the United States proclaimed its obligation to intervene more actively. Conversely, when a group of physicians established a population-based estimate of excess mortality associated with the conflict in Iraq28 that was more than 10 times higher than estimates from other sources, the United States Government simply dismissed the survey figure. Fortunately, the accumulation of quantitative health evidence generated by humanitarian actors often generates a public outcry, forcing political leaders to re-examine their strategies.

Statistics associated with health and mortality indicators are politically sensitive. It is imperative that humanitarian actors exercise technical leadership to enforce statistical coherence, and consequently reduce the negative effects of a political debate more focused on numbers than solutions.

Protection, demobilization and repatriation

Medical doctors, nurses and public health professionals often operate in the vicinity of politics, particularly when they contribute to solving problems in the areas of protection, demobilization, promotion of human rights principles and repatriation.29 However, health professionals have had varying degrees of success in these roles.

In 1993, the United Nations gave the Pan American Health Organization (a World Health Organization regional office), the task of reintegrating 15 000 demobilized combatants of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front into El Salvador’s national health system. The operation was a success: each former combatant was medically screened, all were given treatment when necessary, and re-entered civil society in good health.

The previous year in Haiti, the same organization launched a system of drug supply and distribution (the PROMESS System) across a country ruled by a military junta and subject to a commercial embargo. The system distributed essential medicines through a network of pharmacies during the period of unrest, and subsequently developed a national programme of essential medicines.30

In contrast, the role of physicians in human rights’ observation and monitoring have been less successful. From 1993 to 1995, the dramatically increasing prevalence of physically abused Haitian civilians played an important role in the decision of the International Civil Mission in Haiti to recruit civilian observers with medical training. Doctors were asked to research and report physical abuses, but not to treat the affected individuals. In the long term, the presence of medical staff as observers was technically ambivalent, as their professional commitments based on the Hippocratic Oath often led to therapeutic interventions beyond the scope of human rights observation.31 The healers’ presence in this capacity jeopardized the mission’s political agenda. The collision of humanitarian and political actions within the mission severely weakened its capacity to carry out its mandate.

Tensions between health needs and political obligations appear also in refugee repatriation. The repatriation of 360 000 Cambodian refugees in 1993 was hampered by multidrug-resistant malaria endemic in predominantly Khmer Rouge-controlled areas, as this made repatriation of refugees medically unwise. But this public health argument did not outweigh the political imperative set forth in Cambodia’s Paris peace accord. It was the health sector’s responsibility to take necessary measures for safe refugee repatriation.

Diplomacy, health and peace

The Health as a Bridge for Peace (HBP) project, formally endorsed by the 51st World Health Assembly in May 1998, seeks “the integration of peace-building concerns, concepts, principles, strategies and practices into health relief and health sector development”.32 This multidimensional framework claims to aid peace efforts by enabling communication between warring parties on matters not related to their conflict. The project aims to create a technical space in which opposing groups can agree on such issues as health-care norms and guidelines, epidemiological information exchanges and health system reform strategies.

However as it has been implemented in Angola, Bosnia, eastern Slavonia (Croatia) and Haiti, the project has never yielded a tangible peace dividend.33 At most, health professionals were able to create structures, systems of behaviour, institutions and collective actions that were amenable to a culture of peace, once political arrangements and agreements were otherwise secured. Because conflict is inimical to health, health cannot be a reliable bridge to peace, even if numerous short “humanitarian ceasefires” have allowed immunization campaigns.34 In some occasions, health concerns have even adversely affected peace implementation when health-related stigmas were used to polarize views. In early 1996, for example, soon after the signing of the Dayton Agreement, ostensible concerns relating to HIV/AIDS were used by north-east Bosnian civil authorities to oppose NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) military peacekeeping intervention.

Foreign policy is a function of national interests that often compete with humanitarian principles. Consequently, as these examples illustrate, humanitarian action through health can operate agonistically with foreign policy when officials reaffirm universal standards of human dignity. This requires them to derogate from their “hard power” obligations and compromise on national interests. Yet compliance with international criminal and human rights laws is also a matter of national interest in so far as the country seeks to project a positive image worldwide.

Conclusions

In the context of humanitarian action, health and foreign policy are at odds both by definition and by the responsibilities of the actors involved: when people are trapped in a conflict, maintaining their health is a moral imperative for whoever wants to help. This is a matter of altruism, a priority that should not be negotiated based on national interests. Conversely, establishing and maintaining a peace settlement between warring parties is a matter of interest-based negotiations. The responsible actors differ in these two cases. The international health community (governmental and nongovernmental) must find ways to dialogue constructively with foreign policy officials. They must advocate that altruistic values be incorporated to the greatest possible extent into the functions of foreign policy, and that humanitarian concerns rank high in the hierarchy of these functions.7 The examples given here have shown that health and humanitarian actors cannot lead this dialogue in the absence of committed foreign policy officials. At most, public health professionals have demonstrated a capacity to initiate and contribute to critical problem-solving debates by promoting normative values and evidence. However, they have not succeeded in creating a neutral space for political settlements through health efforts.

This analysis shows the fragility of the health and foreign policy nexus when tested in humanitarian contexts, and therefore prevents its generalization to situations where altruistic and interest-based values are opposed. This nexus could risk the ascendancy of priorities favouring national interests, resulting in a reversal of international health concerns from people-centred values to a narrower understanding of health as a national security issue. Such a risk was acknowledged in general terms in the 2003 report of the Commission on Human Security.35

The unequal consideration of public health concerns in foreign policy agendas shows that proponents of the health and foreign policy nexus are only partially right. Between health and foreign policy, it is unclear which one has the upper hand: health concerns may emerge more substantially in hard-power politics, but this rise does not necessarily suggest that health issues have the capacity to profoundly reconfigure the hierarchy of these functions and provide a bridge between soft and hard power. In fact, it would be premature if not naive to assume that the emergence of health within a foreign policy framework could alter its hierarchy. The hierarchy of interests within foreign policy will remain unless the framework itself is challenged. Health issues are forced to conform to the existing hierarchy of foreign policy functions until policy-makers are willing to pay the costs that change would entail.

The concept of human security offers a middle path or “third way” to mitigate the polarization of foreign policy and humanitarian/health concerns. This middle path would require national governments to “reconfigure foreign policy around human security rather than national security, around health and well-being in addition to the protection of territorial boundaries and economic stability”.36 This implies a widespread recognition of global interdependencies between health and political affairs, and specifically a recognition that health indeed is a precondition for human development and political participation, rather than their outcome. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Panisset UB. An introduction to international health statecraft. In: International health statecraft: Foreign policy and public health in Peru’s cholera epidemic. Lanham (MD): University Press of America; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fidler PD. Health and foreign policy: A conceptual overview. London: Nuffield Trust; 2005. Available from: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/ecomm/files/040205Fidler.pdf

- 3.Fidler DP, Drager N. Health and Foreign Policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:687. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06-035469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen JW, Roberts O. Globalization, health and foreign policy: emerging linkages and interests. Global Health 2005;1(12). Available from: http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/contenet/1/1/12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Nye JS Jr. One world: Health turns into a security priority. International Herald Tribune, 2 September 2002.

- 6.Nye J. Hard and Soft Power. In: Power in the global information age. Oxford: Routlege; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris S. Marrying foreign policy and health: feasible or doomed to fail? Medical Journal of Australia, 2004;180:171-173. Available from http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/180_04_160204/har10834_fm.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mauss M. The gift: the form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. New York: WW Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinowski B. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Long Grove, IL; Waveland Press reprint edition: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godelier M. L’énigme du don [The enigma of the gift]. Paris: Flammarion, collection Champs; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kray K. The “New Humanitarianism”: The Henry Dunant Centre and the Aceh peace negotiations. Princeton: Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs 2004 Case Study 02/03. Available from: http://www.wws.princeton.edu/cases/papers/newhumanit.html

- 12.The code of conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in disaster relief. Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross; 1995. Available from: http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/htm/57JMNB [PubMed]

- 13.Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster response. Geneva: SPHERE Project; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Evans R. The humanitarian challenge: A foreign policy perspective. African Security Review, 1997:6(2). Available from: http://www.iss.co.za/pubs/ASR/6No2/Evans.html

- 15.Médecins Sans Frontières. Nobel Lecture. Oslo: Norwegian Nobel Committee; 1999. Available from: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prize/peace/laureates/1999/msf-lecture.html

- 16.Lambrichs LL. Nous ne verrons jamais Vukovar [We will never see Vukovar]. Paris: Philippe Rey; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brauman R. Penser dans l’urgence. Parcours critique d’un humanitaire [Thinking in emergencies: auto-critique of a humanitarian]. Paris: Seuil; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambrichs L, Thieren M. Dayton plus ten: Europe interrogated. London: Open Democracy; 2005. Available from http://www.opendemocracy.net/conflict-yugoslavia/dayton_3061.jsp

- 19.Macrae J, Leader N. The politics of coherence: humanitarianism and foreign policy in the post-Cold War era. London: Overseas Development Institute; Humanitarian Policy Group Briefing 1, 2000. Available from: http://www.odi.org.uk/hpg/papers/researchinfocus1.pdf

- 20.Principles and good practice of humanitarian donorship. International Meeting on Good Humanitarian Donorship, Stockholm, 2003. Available from: http://www.reliefweb.int/ghd/meetings.html#Stockholm

- 21.Macrae J, Harmer A. Good humanitarian donorship: a mouse or a lion? London: Overseas Development Institute; 2004 Humanitarian Practice Network 24. Available from: http://www.odihpn.org/report.asp?ID=2558

- 22.Evolution of funding by sector over the last 8 years, 1999-2006. Relief Web. Available from: http://ocha.unog.ch/fts2/by_sector.asp

- 23.Thieren M. Health information systems in emergencies. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:561–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PHR calls for intervention to save lives in Sudan: field team compiles indicators of genocide. Boston: Physicians for Human Rights Report; 2004. Available from: http://www.phrusa.org/research/sudan/pdf/sudan_genocide_report.pdf

- 25.Leaning J. Diagnosing genocide: the case of Darfur. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:735–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Documenting atrocities in Darfur. US Department of State: Washington, DC; 2004. State Publication 11182. Available from http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/36028.htm

- 27.Powell C. The crisis in Darfur: testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Washington, DC: US Department of State; 2004. Available from: http://www.state.gov/secretary/former/powell/remarks/36042.htm

- 28.Burnham G, Lafta R, Doocy S, Roberts L. Mortality after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey. Lancet. 2006;368:1421–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geiger HJ, Cook-Degan RM. The role of physicians in conflicts and humanitarian crises. JAMA. 1993;270:616–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tardif F. PROMESS: Une réponse structurante à des besoins fonctionnels [PROMESS: A structuring response to functional needs]. In: Regard sur l’humanitaire. Une analyse de l’expérience haïtienne dans le secteur santé entre 1991 et 1994 [Critical view on humanitarian action: an analysis of the Haitian experience in the health sector between 1991 and 1994]. Paris: Editions de l’Harmattan; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.United Nations. Report of the advanced team of experts mandated by the United Nations to assess the needs for a human rights monitoring mission in Haiti. New York: 1993: UN Document A/47/908. [Google Scholar]

- 32.What is Health as a Bridge for Peace. WHO Health as a Bridge for Peace Project. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/hbp/about/en/print.html

- 33.Hess G, Pfeiffer M. Comparative analysis of WHO “Health as a Bridge for Peace” case studies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. Available from http://www.who.int/hac/techniguidance/hbp/comparative_analysis/en/print/html

- 34.Humanitarian Ceasefires. WHO Health as a Bridge for Peace Project. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/hbp/cease_fires/en/index.html

- 35.Final Report of the Commission on Human Security. New York: Commission on Human Security; 2003. Available from: http://www.humansecurity-chs.org/finalreport/

- 36.Horton R. Iraq: time to signal a new era for health in foreign policy. Lancet. 2006;368:1395–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]