Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of routine antenatal HIV testing for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) in urban Zimbabwe.

Methods

Community counsellors were trained in routine HIV testing policy using a specific training module from June 2005 through November 2005. Key outcomes during the first 6 months of routine testing were compared with the prior 6-month “opt-in” period, and clients were interviewed.

Findings

Of the 4551 women presenting for antenatal care during the first 6 months of routine HIV testing, 4547 (99.9%) were tested for HIV compared with 3058 (65%) of 4700 women during the last 6 months of the opt-in testing (P < 0.001), with a corresponding increase in the numbers of HIV-infected women identified antenatally (926 compared with 513, P < 0.001). During routine testing, more HIV-infected women collected results compared to the opt-in testing (908 compared with 487, P < 0.001) resulting in a significant increase in deliveries by HIV-infected women (256 compared with 186, P = 0.001); more mother/infant pairs received antiretroviral prophylaxis (n = 256) compared to the opt-in testing (n = 185); and more mother/infant pairs followed up at clinics (105 compared with 49, P = 0.002). Women were satisfied with counselling services and most (89%) stated that offering routine testing is helpful. HIV-infected women reported low levels of spousal abuse and other adverse social consequences.

Conclusion

Routine antenatal HIV testing should be implemented at all sites in Zimbabwe to maximize the public health impact of PMTCT.

Résumé

Objectif

Evaluer l’impact d’un dépistage anténatal systématique du VIH sur la prévention de la transmission de la mère à l’enfant de ce virus (PMTCT) dans les zones urbaines du Zimbabwe.

Méthodes

Des conseillers appartenant à la collectivité ont été formés à la politique de dépistage systématique du VIH à l’aide d’un module de formation spécial de juin à novembre 2005. Les principaux résultats obtenus au cours des 6 premiers mois d’application du dépistage systématique ont été comparés à ceux de la période où ce dépistage était pratiqué à la demande et les patientes ont été interrogées.

Résultats

Parmi les 4551 femmes s’étant présentées pour des soins anténataux pendant les 6 premiers mois de proposition systématique d’un dépistage du VIH, 4547 (99,9%) se sont soumises à ce dépistage contre 3058 (65%) parmi les 4700 femmes s’étant présentées pendant les 6 derniers mois de dépistage à la demande (p < 0,001), d’où une augmentation du nombre de femmes contaminées par le VIH détectées avant l’accouchement (926 contre 513, p < 0,001). Pendant la période de dépistage systématique, davantage de femmes contaminées sont venues rechercher leurs résultats que pendant la période de dépistage à la demande (908 contre 487, p < 0,001), ce qui s’est traduit par un accroissement significatif du nombre d’accouchements par des femmes séropositives pour le VIH (256 contre 186, p = 0,001) ; davantage de couples mère/enfant ont reçu un traitement prophylactique antirétroviral (n = 256 contre 185) ; et davantage de couples mère/enfant ont été suivis dans des dispensaires (105 contre 49, p = 0,002). Les femmes ont été satisfaites des conseils fournis et la plupart (89%) ont déclaré que la proposition systématique d’un dépistage était utile. Les femmes contaminées par le VIH ont signalé de faibles niveaux de maltraitances conjugales et autres phénomènes sociaux préjudiciables.

Conclusion

Le dépistage systématique du VIH doit être mis en œuvre dans tous les sites du Zimbabwe pour maximiser le bénéfice pour la santé de la PMTCT.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar el impacto de la prueba prenatal sistemática de detección del VIH en la prevención de la transmisión del VIH de la madre al niño (PTMN) en una zona urbana de Zimbabwe.

Métodos

Se formó a consejeros comunitarios en la política de realización sistemática de la prueba del VIH utilizando un módulo didáctico específico entre junio y noviembre de 2005. Los resultados principales obtenidos durante los 6 primeros meses de pruebas sistemáticas (sistema con derecho a renuncia, «opt-out») se compararon con el periodo con derecho de adhesión («opt-in») de los 6 meses previos, y se entrevistó a las usuarias.

Resultados

De las 4551 mujeres que realizaron una visita de atención prenatal durante los 6 primeros meses de pruebas sistemáticas de detección del VIH, 4547 (99,9%) fueron sometidas a la prueba del VIH, en comparación con 3058 (65%) de 4700 durante los 6 últimos meses de pruebas con derecho de adhesión (P < 0,001), aumentando así el número de mujeres seropositivas identificadas en la etapa prenatal (926 frente a 513, P < 0,001). Durante el periodo de pruebas sistemáticas, el número de mujeres infectadas que acudieron por los resultados fue mayor que entre las mujeres con derecho de adhesión (908 frente a 487, P < 0,001), lo que se tradujo en un aumento importante del número de partos por mujeres VIH-positivas (256 frente a 186, P = 0,001); el número de parejas madre/lactante que recibieron profilaxis antirretroviral fue consiguientemente mayor (n = 256) en comparación con el periodo con derecho de adhesión (n = 185); y lo mismo ocurrió con el número de parejas madre/lactante que se sometieron a seguimiento en consultorios (105 frente a 49, P = 0,002). Las mujeres estaban satisfechas con los servicios de asesoramiento (89%), y la mayoría consideraban conveniente el ofrecimiento de pruebas sistemáticas. Las mujeres VIH-positivas refirieron bajos niveles de violencia conyugal y otros efectos sociales adversos.

Conclusión

Si se quiere optimizar el impacto de la PTMN en la salud pública, es necesario implementar en todo Zimbabwe las pruebas prenatales sistemáticas de detección del VIH.

ملخص

الەدف

تقييم أثر الاختبارات الروتينية لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري قبل الولادة على توقي سراية الفيروس من الأم إلى الطفل، في المناطق الحضرية في زمبابوي.

الطريقة

دُرِّب مقدمو المشورة المجتمعية في مجال سياسة الاختبارات الروتينية لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري، باستخدام وحدة تدريب نموذجية نوعية، خلال الفترة من حزيران/يونيو 2005، إلى تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر 2005. وقورنت الحصائل الأساسية لفترة الأشەر الستة الأولى للاختبارات الروتينية، مع فترة الأشەر الستة السابقة التي أجريت فيەا الاختبارات وفقاً لنەج خيار القبول، وأجريت مقابلات مع الخاضعات لەذە الفحوصات.

الموجودات

من بين 4551 سيدة قَدِمْنَ لتلقي رعاية الحمل خلال الأشەر الستة الأولى لإجراء اختبارات فيروس العوز المناعي البشري الروتينية، أجرت 4547 سيدة (99.9%) ەذە الاختبارات مقارنة بـ 3058 سيدة (65%) من بين 4700 سيدة، خلال فترة الأشەر الستة الأخيرة التي أجريت فيەا الاختبارات وفقا لنەج خيار القبول (قيمة الاحتمال أقل من 0.001)، مع وجود زيادة مناظرة في أعداد النساء المصابات بفيروس العوز المناعي البشري اللاتي اكتُشفت إصابتەن خلال فترة الحمل (926 سيدة مقارنة بـ 513، بقيمة احتمال أقل من 0.001). وتبين خلال فترة إجراء الاختبارات، أن عدداً أكبر من النساء المصابات بالفيروس جئن لمعرفة النتائج، مقارنة بالفترة التي أجريت فيەا الاختبارات وفقاً لنەج خيار القبول (908 مقارنة بـ 487، بقيمة احتمال أقل من 0.001) مما أدى إلى حدوث زيادة يعتد بەا إحصائياً في عدد الولادات التي تمت لنسوة مصابات بفيروس العوز المناعي البشري (256 مقارنة بـ 186، بقيمة احتمال مقدارەا 0.001)، وتلقي عدد أكبر من كل من الأم والرضيع للعلاج الوقائي بمضادات الفيروسات القەقرية (عدد: 256) مقارنة بفترة الاختبارات التي أجريت وفقاً لنەج خيار القبول (عدد: 185)، ومتابعة عدد أكبر من كل من الأمەات والرضع في العيادات (105 مقارنة بـ 49، بقيمة احتمال مقدارەا 0.002). وأبدت النسوة رضاءەن عن خدمات المشورة المقدمة، وذكر معظمەن (89%) أن عرض إجراء الاختبارات الروتينية أمر مفيد. وكانت معدلات إبلاغ النسوة المصابات بەذا الفيروس عن اعتداء أزواجەن عليەن، وغير ذلك من العواقب الاجتماعية الضائرة منخفضة.

الاستنتاج

ينبغي تطبيق الاختبارات الروتينية لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري في جميع المناطق في زمبابوي لزيادة الآثار الصحية العمومية لتوقي سراية الفيروس من الأم إلى الطفل، إلى أقصى حد.

Introduction

The perinatal HIV epidemic remains a major public health problem in Zimbabwe.1 Recent estimates indicate that over 20% of women aged 15–49 years presenting for antenatal care (ANC) are HIV-infected.1 Several trials have reported the efficacy of simple, low-cost antiretroviral prophylactic regimens to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.2–4 Although prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) interventions using single-dose nevirapine (sdNVP) have been implemented in many urban and rural clinics in Zimbabwe,5 uptake of these interventions remains low, primarily due to poor antenatal HIV testing rates.6

Detection of maternal infection early in pregnancy through voluntary counselling and HIV testing (VCT) is critical for PMTCT.7 In Zimbabwe, HIV testing is conducted after individual pre-test counselling, with clients actively choosing whether to be tested (i.e. an “opt-in” approach or client-initiated testing). The acceptance rate of VCT among our ANC clients has been low, ranging from 20% to 63%.6,8 Several reasons may account for poor antenatal VCT uptake among women in sub-Saharan Africa, including absence of prenatal care, fear of stigma and inadequate counselling experiences.9–11 Thus innovative approaches to antenatal HIV testing are urgently required.

Provider-initiated routine antenatal HIV testing (i.e. an “opt-out” approach) is the standard of care in the United States of America (USA) and other developed nations.12–16 Routine antenatal HIV testing policy is rare in sub-Saharan Africa.17,18 Recent data from the PMTCT programme in Botswana demonstrated that routine HIV testing led to a significant increase in HIV-test acceptance at ANC clinics, where HIV prevalence has been ≥ 40% since 1995.18 A recent study from rural Zimbabwe found that routine antenatal HIV testing is acceptable to both clients and health-care providers.19 The objective of this pilot study was to evaluate the impact of routine antenatal HIV testing in urban Zimbabwe.

Methods

Zimbabwe is a southern African country of approximately 12.5 million inhabitants whose capital city, Harare, has a population of 1.5 million. Antenatal HIV seroprevalence in urban clinics has been estimated to be around 21.3%.20 Our study was conducted at four antenatal clinics in Chitungwiza, a socioeconomically disadvantaged community 25 km south of Harare.

Provider-initiated routine HIV testing with right of refusal was offered to all new ANC clients between June 2005 and November 2005. Before implementation of the routine HIV testing policy, a VCT site instrument was used to assess the adequacy of staffing levels, adherence to PMTCT protocols, availability of health education materials, availability of test kits and medical consumables, adherence to staff roles and responsibilities, and general aspects of site operations. A counsellor reflection form and a VCT client exit survey form were used to guide the implementation of the routine HIV testing policy.

Community mobilization activities for improving public awareness of the routine HIV testing policy were carried out by community outreach counsellors. A drama skit was developed and presented at health worker in-service training workshops and at the community advisory board meetings for critiques and comments before presentation. The community counsellors performed the skit on a rotational basis at the four clinics on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday mornings for new ANC clients and during the afternoons in the community and at colleges, churches and industrial facilities.

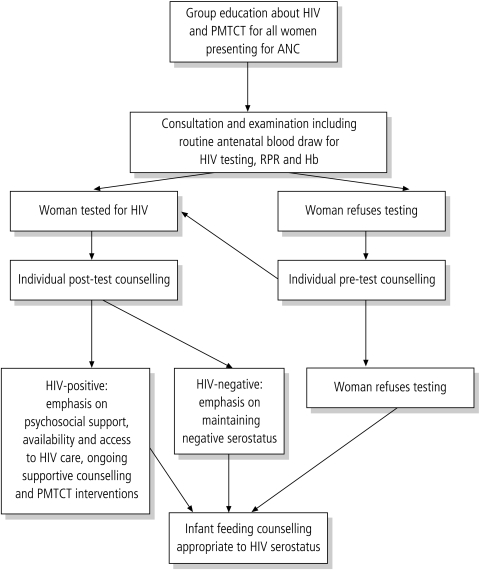

Before implementation of the routine HIV testing policy, clinic staff members at the four sites attended a two-day training session conducted by the PMTCT programme staff in which the new strategy was discussed in detail, including data collection and interview techniques. Fig. 1 depicts the routine HIV testing algorithm that was modified from the pilot project on routine HIV testing in Botswana18 and implemented for all new ANC clients.

Fig. 1.

Provider-initiated routine HIV counselling and testing algorithm

ANC, antenatal care; Hb, haemoglobin; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV; RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

Under the new system, existing PMTCT clinic counsellors held 15-minute group education and discussion sessions with pregnant women, using a structured flip chart as a discussion guide. The discussion focused on HIV transmission, PMTCT, sdNVP prophylaxis and routine HIV testing for all mothers, specifying the right to refuse. Women who did not want any one of the routine antenatal tests were referred for individual pre-test counselling to discuss their concerns. Women who arrived for ANC when no group was conducted received the same education individually via pre-test counselling. Women who did not refuse and gave verbal informed consent individually had blood drawn for rapid HIV testing on-site by clinic nurses in addition to routine syphilis, blood group and haemoglobin level testing.

Maternal HIV status was determined on-site using two rapid tests in parallel (Uni-Gold Test, Trinity Biotech, USA; and Determine HIV1/2 test, Abott Laboratories, USA) on each blood sample, and a third test (OraQuick, Abott Laboratories, USA) as a tie-breaker. Women received their test results the same day during extensive individual post-test counselling, with a focus on PMTCT interventions for HIV-infected women, enrolment into support groups, counselling for exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months according to WHO and national guidelines, sdNVP prophylaxis and mother-infant follow-up.

To assess the acceptability of the routine HIV testing policy, a 15-item self-administered exit questionnaire was administered during the initial three months of implementation to women (n = 2011) in Shona, the local language, after completion of their first ANC visit. The questionnaire was adapted from the pilot project on routine HIV testing in Botswana.18

To determine if there were any negative effects related to the routine HIV testing policy, women (n = 221) attending the four antenatal and postnatal clinics who had participated in routine HIV testing were interviewed individually, regardless of HIV status, during the fifth month of study implementation. The standardized questionnaire was administered in Shona by four trained community counsellors who did not know the client’s serostatus.

Data collection and analysis

Quantitative data regarding acceptance of HIV testing and PMTCT interventions were collected according to current programme guidelines. Data was entered and analysed using EpiInfo 2004 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Impact on HIV testing acceptance rates, post-test return rates, acceptance of PMTCT interventions and follow-up were determined by comparing data collected during the first 6 months of routine HIV testing (opt-out) with the prior 6 months opt-in period. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The Call-to-Action Project was approved by Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, the Chitungwiza Health Department and the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest University Health Sciences. Verbal informed consent was obtained individually from all participants after explaining the study protocol in detail. Strict confidentiality was maintained for all clients.

Results

Of the 4551 pregnant women presenting for ANC during the first 6 months (June 2005 to November 2005) of routine HIV testing, 4547 (99.9%) were tested for HIV compared with 3058 (65%) of 4700 pregnant women during the last 6 months (October 2004 to March 2005) of the opt-in testing period (P < 0.001), with a corresponding increase in the numbers of HIV-infected women identified antenatally (n = 926, 20.4% seroprevalence, as compared with 513, 16.8% seroprevalence, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected indicators of the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in four urban antenatal clinics included in the Call-to-Action programme in urban Zimbabwe.

| Indicator | October 2004–March 2005 (“Opt-in” VCT approach or client-initiated testing) Number (%) | June 2005–November 2005 (“Opt-out” VCT approach or routine testing) Number (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VCT | |||

| ANC bookings | 4872 | 4551 | – |

| Pre-test counselled/group education | 4872 (100%) | 4551 (100%) | – |

| Tested for HIV | 3058 (65.1%) | 4547 (99.9%)a | < 0.001 |

| Women HIV-infected | 513 (16.8%) | 926 (20.4%)a | < 0.001 |

| Post-test counselled | 2964 (96.9%) | 4538 (99.8%)a | < 0.001 |

| Partners tested for HIV | 196 (6.4%) | 308 (6.8%) | 0.531 |

| Partners post-test counselled | 196 (100%) | 307 (99.7%) | – |

| Partners HIV-infected | 44 (22.4%) | 49 (15.9%) | 0.065 |

| HIV-infected women | |||

| Post-test counselled and collected test results | 487 (95%) | 908 (98%)a | < 0.001 |

| Given sdNVP to take home at ≥ 28 weeks of gestation | 372 (76.3) | 663 (71.6%) | 0.711 |

| Known to have delivered in the four antenatal clinics | 186 (38.1%) | 256 (27.6%)a | ≤ 0.001 |

| Total infants receiving sdNVP | 185 (36%) | 257 (28%)b | – |

| Mothers and infants receiving sdNVP | 185 (36%) | 256 (28%) | – |

| Care, support and follow-up | |||

| Mothers enrolled in mentorship programme | 257 (52.7%) | 526 (57.9%) | 0.064 |

| Mothers joining PSS group | 42 (16.3%) | 80 (15.2%) | 0.681 |

| Mother-infant pairs seen at the 6-week visit | 49 (26.3%) | 105 (41%)a | 0.002 |

ANC, antenatal care; PSS, psychosocial support; sdNVP, single-dose nevirapine; VCT, voluntary counselling and HIV testing. a Statistically significant. b Twin gestation.

No negative effects were noted on ANC attendance, collection of test results, post-test counselling rates or uptake of PMTCT interventions among HIV-infected women during the implementation of routine HIV testing. Overall, 4538 (99.8%) women returned to collect their test results during the routine antenatal HIV testing period compared to 2964 (96.7%) during opt-in testing period (P < 0.001) (Table 1). During the routine testing period, more HIV-infected women were identified antenatally (926 compared with 513, P < 0.001). Of these, significantly more HIV-infected women were post-test counselled and collected test results compared to the opt-in period (908 compared with 487, P < 0.001). Likewise, there was a corresponding increase in deliveries by known HIV-infected women in the four clinics (256 compared with 186, P ≤ 0.001), resulting in higher numbers of mother/infant pairs receiving sdNVP prophylaxis during routine testing (n = 256) compared to the opt-in testing period (n = 185). In addition, more HIV-infected women during the routine testing period enrolled in the mentorship programme led by community counsellors (526 compared with 257, P = 0.064), joined psychosocial support groups (80 compared with 42, P = 0.681), and followed up with their babies at the clinics (105 compared with 49, P = 0.002) compared with women during the opt-in study period.

Of the 4547 women who underwent routine HIV testing and were encouraged to bring their partners for free VCT, only 308 men (6.8%) opted for HIV testing, and 307 (99.7%) returned to collect their results and received post-test counselling; of these, 49 (16%) were HIV-infected.

Client exit survey

Of the 2624 women who opted for routine HIV testing during the first 3 months of study and answered the questionnaire at the end of their first ANC visit, 2011 (76.6%) completed the exit survey. The overall response was positive, with clients generally satisfied with the quality of counselling. Overall, 98% of respondents said that the information they were given by community counsellors on routine HIV testing had adequately prepared them for the result, 99% of women said they understand why their blood was being drawn, 99% of women said they were better prepared to manage their health after learning their HIV status and 98% said they were ready to disclose their HIV status to their partners.

Follow-up survey

A total of 221 women attending antenatal and postnatal clinics who opted for routine testing were sampled and interviewed individually, regardless of their HIV status, to determine if there were any negative effects of routine HIV testing. The sample’s sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 24 years, with most women married (90%), educated through secondary school (82%) and employed (67%). Of the 221 women interviewed, 219 (99%) were tested for HIV at the first antenatal visit; 109 women (49%) were HIV-infected. The most frequent reasons given for accepting the HIV test were to protect their children and concern for their own health. All women found the information provided by community counsellors adequate to make informed decisions about routine HIV testing.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of women who participated in a follow-up interview during the routine HIV testing pilot project (n = 221).

| Characteristics | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 15–25 | 151 | 68.4 |

| 26–35 | 54 | 24.4 |

| 36–45 | 16 | 7.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 10 | 4.5 |

| Married | 199 | 90.0 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.5 |

| Living with partner | 11 | 5.0 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 53 | 24.0 |

| 1 | 88 | 39.8 |

| 2 | 53 | 24.0 |

| 3 | 19 | 8.6 |

| 4 or more | 8 | 3.6 |

| Level of education | ||

| Primary | 38 | 17.1 |

| Secondary | 181 | 82.0 |

| Tertiary | 2 | 0.9 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 147 | 66.5 |

| Unemployed | 74 | 33.5 |

Of 221 women interviewed, 88% (194) had disclosed their serostatus to their husbands (Table 3). Among those women who disclosed their test results (n = 197), 181 (92%) did not experience violence and the relationship continued. However, only 7% of the partners were tested for HIV. Disclosure-related violence from their partners was experienced by 8% [16 (14 HIV-infected, 2 HIV-uninfected) women]. The patterns of physical abuse included pushing, slapping and kicking; no injuries related to firearms, knife or burns were reported. The relationship ended in 4 couples (2%) due to divorce (1), separation (1), and abandonment by the male partner (2). Of 221 women interviewed, 11% (24) had not disclosed their serostatus to anyone. The reasons given for non-disclosure included fear of violence, divorce and stigma.

Table 3. Disclosure of HIV serostatus among women participating in “opt-out” HIV testing (n = 221)a .

| Response | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Person informed | ||

| Husband | 197 | 89.1 |

| Relative | 33 | 14.9 |

| Friend | 5 | 2.3 |

| None | 24 | 10.9 |

| Reason for non-disclosure (n = 24) | ||

| Afraid of violence | 8 | 33.3 |

| Afraid of divorce | 6 | 25.0 |

| Afraid of stigma | 5 | 20.8 |

| Thought not useful | 2 | 8.3 |

| No response | 7 | 29.2 |

| Partners’ response (n = 197) | ||

| No violence/relationship continued | 181 | 91.8 |

| Violence | 16 | 8.1 |

| Relationship stopped | 4 | 2.0 |

| Partner tested | 13 | 6.6 |

| Opinion of women on routine antenatal HIV testing (n = 221) | ||

| Helpful | 197 | 89.1 |

| Not helpful | 24 | 10.9 |

a This was a multiple response question and hence the percentages add up to more than 100%.

Overall, 89% (197 of 221) women stated that offering routine HIV testing like other blood tests during pregnancy is helpful because it is an empowering tool for women to exercise their rights and responsibilities by accessing relevant information to make informed decisions about PMTCT and infant feeding.

Discussion

We found that routine antenatal HIV testing was feasible and acceptable for pregnant women in urban Zimbabwe, resulting in almost 100% of women opting for HIV testing, and overall significant improvement in quantitative PMTCT service statistics. Our data are consistent with recent reports from Africa, where routine antenatal HIV testing has been found to be acceptable and to significantly increase the HIV testing rates.17,18

The significantly high uptake at our site with routine HIV testing could be related to multiple factors. Women were probably less fearful of participating in routine HIV testing because this approach would be perceived by her partner and family as “standard of care” offered to all ANC clients, thereby reducing the risk of stigma and other adverse social consequences when compared to the opt-in VCT policy. In addition, community sensitization, counselling sessions involving highly motivated community counsellors and availability of on-site rapid HIV testing may also have contributed to significantly high HIV testing rates among women in our study.

Another important finding in this study was that the introduction of routine HIV testing did not lead to reductions in the number of women attending ANC or those receiving test results compared to the opt-in period. In our study, 98% of HIV-infected women returned for test results. Improved community awareness and group education about the importance of routine antenatal HIV testing and availability of on-site rapid testing with same-day results may explain the above findings. In contrast, a recent study in Botswana showed that a significant proportion of pregnant women (29%) who opted for routine HIV testing did not return to the clinic to collect their test results because HIV testing was conducted off-site and results were not immediately available.18 Likewise, in the Kenya study where routine antenatal HIV testing was offered, 31% of women (including 44% of HIV-infected women) did not return to obtain their test results.17

Policies to encourage early detection of HIV infection during pregnancy through routine testing have raised several ethical concerns regarding the definition and implementation of routine universal testing, especially in settings marked by poverty, illiteracy, gender inequalities, weak health-care infrastructure and poor access to antiretroviral treatment.21,22 Recently, a population-based survey from Botswana found that routine HIV testing was widely supported and reduced barriers to HIV testing.23 In the present study, the overall response to routine HIV testing was positive, with relatively low levels of miscomprehension and partner violence, which is often a major concern for HIV-infected women when they disclose their infection status.9,24 Furthermore, more than two-thirds of newly HIV-infected women at our site joined support groups, a vital component for any successful PMTCT programme.

Several challenges were identified during the implementation of this routine antenatal HIV testing project. First, the clinics are severely understaffed with regard to nurses. Nurses are often trained in counselling, but the increased clinic workload due to staff shortage has resulted in reluctance among staff members to take on the additional task of counselling. In addition, there are no funds to employ and train a new cadre of full-time professional counsellors to deliver VCT. Therefore, HIV counselling has been conducted by community counsellors at our site since 1998, a solution that has been replicated at many antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe.6 This focus on group talk and discussion both reduces the pre-test counselling burden on health-care workers and facilitates individual post-test counselling for both HIV-negative and HIV-positive women. Second, the current economic hardships in Zimbabwe and high levels of midwife staff turnover requires more resources to be made available for training, especially to effectively communicate the new routine HIV testing approach and dispel the misconception that it is mandatory testing. Intensive standardized health worker training at all levels of health service delivery is warranted. It is important to ensure proper logistic support and availability of laboratory supplies before the routine testing policy is implemented all over the country. Finally, countrywide public awareness campaigns through print and electronic media before the implementation of the routine antenatal HIV testing are critical.

The low rate of HIV testing among male partners remains a major challenge for the PMTCT programme in Zimbabwe. Innovative approaches to promote male involvement are urgently needed. PMTCT programmes should address gender-based issues, make ANC clinics more male-friendly, promote couple counselling and HIV testing, and enhance community mobilization and information-education-communication (IEC) activities to promote VCT among men.7

Significant advances have occurred in PMTCT.24 In resource-rich settings, perinatal HIV transmission rates are less than 2% due to widespread implementation of prenatal HIV-1 testing, combination antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy, elective caesarean section and avoidance of breastfeeding.25 Therefore, routine HIV testing has become the standard of care for pregnant women in resource-rich countries.12–16 In contrast, routine HIV testing approach is unusual in sub-Saharan Africa,17,18 where HIV infection rates are very high and HIV testing faces considerable barriers, including the fear of stigma and discrimination.9,10 Although there has been scale-up of PMTCT in many resource-poor settings, ARV treatment programmes have only recently started to become available. In 2004, to increase access to PMTCT and ARV therapy in resource-limited countries, the UNAIDS/WHO recommended routine HIV testing of pregnant women with the right to refuse.26

Our study has certain limitations. The almost 100% antenatal HIV testing acceptance rate at our clinics could be attributed to the highly motivated clinic staff. The community counsellors are people living with HIV/AIDS who have participated in previous PMTCT clinical trials at our site. This may not be the case at other antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe. The study findings are limited in terms of overall generalization and impact since only 25% of HIV-infected women identified in the city of Chitungwiza actually deliver in the clinics; most women deliver in other urban or rural facilities or at home. Despite these limitations, we believe that our pilot data provide useful information for implementing routine antenatal HIV testing policy in Zimbabwe.

To our knowledge, this study was the first to evaluate routine HIV testing in a large urban PMTCT programme in Zimbabwe. Although implementation was challenging given the scarcity of human and financial resources, we observed that routine HIV testing was operationally feasible and acceptable to all women, with significant improvement in quantitative PMTCT service statistics. In addition, HIV-infected women who participated in routine testing reported relatively low levels of spousal abuse and other adverse social consequences. High-quality post-test counselling and adequate staffing are critical before widespread implementation of routine HIV testing. We believe that routine antenatal HIV testing should become the standard of care and be urgently implemented at all antenatal sites in Zimbabwe. Given the high antenatal HIV prevalence, implementing routine HIV testing would have a significant public health impact on the perinatal HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe and other resource-limited countries. ■

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and Chitungwiza Health Department, Family AIDS Initiatives Programme Partners, ISPED and Kapnek Trust, Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation administrative and technical staff including Patricia Mbetu, Jo Keatinge, Matthews Maruva, Chuck Hoblitzelle, Maurice Adams and Catherine Wilfert. We also thank Godfrey Woelk, Tsungai Chipato, Rose Kambarami, the UZ-UCSF Collaborative Program in Women’s Health, the departments of paediatrics, community medicine and obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Zimbabwe School of Medicine, PMTCT Partnership Forum, Tracy Creek (CDC Botswana), Shannon Hader (CDC Zimbabwe), Zimbabwe AIDS Prevention Project-Call-to-Action team, nurses, community counsellors, mobilizers and all the mothers and infants who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation and United States Agency for International Development. Parts of this paper were presented at the XIV International AIDS Conference, 13–18 August 2006 in Toronto, Canada.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mahomva A, Greby S, Dube S, Mugurungi O, Hargrove J, Rosen D, et al. HIV prevalence and trends from data in Zimbabwe, 1997-2004. Sex Transm Inf. 2006;82:42–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leroy V, Karon JM, Alioum A, Ekpini ER, Meda N, Greenberg AE, et al. Twenty-four month efficacy of a maternal short-course zidovudine regimen to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in West Africa. AIDS. 2002;16:631–41. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.PETRA Study Team Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra Study): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1178–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;354:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez F, Mukotekwa T, Miller A, Orne-Gliemann J, Glenshaw M, Chitsike I, et al. Implementing a rural programme of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Zimbabwe: first 18 months of experience. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:774–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shetty AK, Moyo M, Mhazo M, von Lieven A, Mateta P, Katzenstein DA, et al. The feasibility of voluntary counseling and HIV testing for pregnant women using community volunteers in Zimbabwe. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:755–9. doi: 10.1258/095646205774763090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassett MT. Ensuring a public health impact of programs to reduce HIV transmission from mothers to infants: the place of voluntary counseling and testing. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:347–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stranix-Chibanda L, Chibanda D, Chingono A, Montgomery E, Wells J, Maldonado Y, et al. Screening for psychological morbidity in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected pregnant women using community counselors in Zimbabwe. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2005;4:83–8. doi: 10.1177/1545109706286555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcome of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta GR. How men’s power over women fuels the HIV epidemic. BMJ. 2002;324:183–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Painter TM, Diaby KL, Matia DM, Lin LS, Sibailly TS, Kouassi MK, et al. Women’s reasons for not participating in follow-up visits before starting short course antiretroviral prophylaxis for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2004;329:543–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7465.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC Revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR. 2001;50:59–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC HIV testing among pregnant women – United States and Canada, 1998-2001. MMWR. 2002;51:1013–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayaraman GC, Preiksaitis JK, Larke B. Mandatory reporting of HIV infection and opt-out prenatal screening for HIV infection: effect on testing rates. CMAJ. 2003;168:679–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stringer EM, Stringer JS, Oliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Goepfert AR. Evaluation of a new testing policy for human immunodeficiency virus to improve screening rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1104–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson WM, Johnstone ED, Goldhert DJ, Gormley SM, Hart GJ. Antenatal HIV testing assessment of a routine, voluntary approach. BMJ. 1999;318:1660–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7199.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James K, Nduati R, Kamau K, Janet M, Grace J. HIV-1 testing in pregnancy: acceptability and correlates of return for test results. AIDS. 2000;14:1468–70. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care – Botswana, 2004. MMWR. 2004;53:1083–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez F, Zvandaziva C, Engelsmann B, Dabis F. Acceptability of routine HIV testing (“opt-out”) in antenatal services in two rural districts of Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:514–20. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191285.70331.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimbabwe Ministry of Health. National survey of HIV and syphilis prevalence among women attending antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe, 2004. Harare: Zimbabwe Ministry of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo B, Wolf L, Sengupta S. Ethical issues in early detection of HIV infection to reduce vertical transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:S136–43. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012152-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rennie S, Behets F. Desperately seeking targets: the ethics of routine HIV testing in low-income countries. Bull World Health Org. 2006;84:52–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.05.025536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiser SD, Heisler M, Leiter K, Percy-de Korte F, Tlou S, DeMonner S, et al. Routine HIV testing in Botswana: a population-based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaillard P, Melis R, Mwanyumba F, Claeys P, Muigai E, Mandaliya K, et al. Vulnerability of women in an African setting: lessons for mother-to-child HIV transmission prevention programmes. AIDS. 2002;16:937–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200204120-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mofenson LM. Advances in the prevention of vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2003;14:295–308. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS Global Reference Group on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights. UNAIDS/WHO policy statement on HIV testing. Available at: http://www.who.int/pub/vct/en/hivtestingpolicty04.pdf