Abstract

Objective

Literature on human resources for health in Africa has focused on personal health services. Little is known about graduate public health education. This paper maps “advanced” public health education in Africa. Public health includes all professionals needed to manage and optimize health systems and the public’s health.

Methods

Data were collected through questionnaires and personal visits to departments, institutes and schools of community medicine or public health. Simple descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data.

Findings

For more than 900 million people, there are fewer than 500 full-time staff, around two-thirds of whom are male. More men (89%) than women (72%) hold senior degrees. Over half (55%) of countries do not have any postgraduate public health programme. This shortage is most severe in lusophone and francophone Africa. The units offering public health programmes are small: 81% have less than 20 staff, and 62% less than 10. On the other hand, over 80% of Africans live in countries where at least one programme is available, and there are six larger schools with over 25 staff. Programmes are often narrowly focused on medical professionals, but “open” programmes are increasing in number. Public health education and research are not linked.

Conclusion

Africa urgently needs a plan for developing its public health education capacity. Lack of critical mass seems a key gap to be addressed by strengthening subregional centres, each of which should provide programmes to surrounding countries. Research linked to public health education and to educational institutions needs to increase.

Résumé

Objectif

La littérature sur les ressources humaines pour la santé en Afrique s’intéresse principalement aux services de santé individuelle. On dispose de peu de connaissances sur les formations universitaires en santé publique. Le présent article cartographie les formations « avancées » en santé publique dispensées en Afrique. La santé publique regroupe tous les professionnels nécessaires à la gestion et à l’optimisation des systèmes de santé et de la santé publique elle-même.

Méthodes

Des données ont été recueillies à travers des questionnaires et des visites individuelles dans des départements, des instituts et des écoles de médecine communautaire ou de santé publique. Des méthodes statistiques descriptives simples ont été utilisées pour analyser ces données.

Résultats

Pour plus de 900 millions de personnes, le personnel de formation en santé publique n’atteint même pas 500 personnes à plein temps, dont deux tiers d’hommes. La proportion de détenteurs d’un diplôme supérieur est plus forte chez les hommes (89%) que chez les femmes (72%). Plus de la moitié des pays (55%) ne disposent pas de programme d’enseignement en santé publique de troisième cycle. Cette pénurie est plus sévère en Afrique lusophone et francophone. Les unités proposant des programmes de santé publique sont peu étoffées : 81% d’entre elles emploient moins de 20 personnes et 62% d’entre elles moins de 10. Par ailleurs, plus de 80% des Africains vivent dans un pays bénéficiant d’au moins un programme dans ce domaine et il existe six grandes écoles employant plus de 25 personnes. Les programmes de santé publique s’adressent souvent de manière limitative aux professionnels de santé, mais le nombre des programmes « ouverts » est en augmentation. Il n’y a pas de liens entre la formation et la recherche en santé publique.

Conclusion

L’Afrique a besoin d’urgence d’un plan de développement de ses capacités de formation en santé publique. L’absence de masse critique semble un problème essentiel auquel il faudra remédier par un renforcement des centres subrégionaux, dont chacun délivrera des programmes aux pays environnements. Il faut aussi accroître les connexions entre la recherche liée à la formation en santé publique et les établissements d’enseignement dans ce domaine.

Resumen

Objetivo

Las publicaciones sobre los recursos humanos para la salud en África se han centrado en los servicios de salud personales, pero poco se sabe sobre la formación en salud pública impartida a los graduados. En este artículo se mapea la formación en salud pública «avanzada» en África. La salud pública abarca a todos los profesionales necesarios para gestionar y optimizar los sistemas de salud y la salud de la población.

Métodos

Se reunieron datos mediante cuestionarios y visitas personales a departamentos, institutos y escuelas de medicina comunitaria o de salud pública, y se usaron estadísticas descriptivas sencillas para analizar esos datos.

Resultados

Para más de 900 millones de habitantes, se cuenta con menos de 500 personas a tiempo completo, unas dos terceras partes de las cuales son hombres. Éstos poseen un título superior en mayor grado (89%) que las mujeres (72%). Más de la mitad (55%) de los países carecen de un programa de salud pública de posgrado. Esa escasez reviste la máxima gravedad en el África lusófona y francófona. Las unidades que ofrecen programas de salud pública son pequeñas: el 81% tienen una plantilla de menos de 20 personas, y el 62% de menos de 10. Por otro lado, más del 80% de los africanos viven en países en los que funciona como mínimo un programa, y hay seis grandes escuelas con una plantilla de más de 25 personas. Los programas suelen estar muy centrados en los profesionales médicos, pero el número de programas «abiertos» es cada vez mayor. La formación y las investigaciones en salud pública no están ligadas.

Conclusión

África necesita urgentemente un plan para desarrollar su capacidad de formación en salud pública. La falta de una masa crítica parece un problema clave que habrá que abordar reforzando los centros subregionales, cada uno de los cuales debería proporcionar programas a los países del entorno. Es preciso ampliar las investigaciones vinculadas a la formación en salud pública y a los centros docentes.

ملخص

Abstract

الغرض

ركَّزت الدراسات المنشورة حول الموارد البشرية الصحية في أفريقيا على الخدمات الصحية الشخصية. ولا يُعرف إلى القليل عن التعليم العالي في مجال الصحة العمومية. وتبيِّن ەذە الورقة وضع التعليم العالي في مجال الصحة العمومية في أفريقيا. ويندرج تحت فئة العاملين في الصحة العمومية جميع المەنيـِّين اللازمين لإدارة وتحسين أداء النُظُم الصحية والصحة العمومية.

الطريقة

تم جمع بيانات من خلال الاستبيانات والزيارات الشخصية إلى الإدارات والمعاەد والكليات المختصة بالصحة العمومية أو طب المجتمع. واستُخدمت طرق الإحصاء الوصفيَّة البسيطة لتحليل البيانات.

الموجودات

بيَّنت الدراسة أن عدد العاملين المتفرغين لرعاية 900 مليون شخص يقل عن 500 عامل، وأن حوالي ثلثيەم ەم من الذكور. كما بينت أن نسبة الحاصلين على درجات علمية عالية تـزيد بين الذكور (89%) على الإناث (72%). بل إن أكثر من نصف البلدان (55%) ليس لديەا أي برامج للصحة العمومية في مستوى الدراسات العليا. ويشتد ەذا النقص في البلدان الأفريقية الناطقة بالبرتغالية والناطقة بالفرنسية. ويلاحظ أيضاً أن الوحدات التي تقدِّم برامج الصحة العمومية صغيرة الحجم: فنحو 81% منەا يعمل بەا أقل من 20 من العاملين، ونحو 62% منەا يعمل بەا أقل من 10 من العاملين. ومن ناحية أخرى، نجد أن أكثر من 80% من الأفارقة يعيشون في بلدان يُقدَّم بەا برنامج واحد على الأقل، وأن ەناك ست كليات أكبر حجماً يعمل بەا أكثر من 25 من العاملين. وتـركِّز البرامج غالباً على المەنيـِّين الطبيـِّين، ولكن يُلاحظ أن عدد البرامج (( المفتوحة )) آخذ في الزيادة. ولم يُلاحظ ارتباط بين التعليم والبحوث في مجال الصحة العمومية.

الاستنتاج

تحتاج أفريقيا إلى خطة عاجلة لتطوير قدراتەا التعليمية في مجال الصحة العمومية. ويمثل الافتقار إلى النواة الأساسية فجوة رئيسية ينبغي التصدِّي لەا عن طريق تعزيز المراكز دون الإقليمية، بحيث يقدِّم كل منەا برامج للبلدان المحيطة بە. كما ينبغي زيادة البحوث المرتبطة بتعليم الصحة العمومية والمؤسسات التعليمية.

Introduction

In most African countries, health is in crisis. Staffing and resourcing remain serious problems in all aspects of health care,1 including essential public health functions and research.2 At the same time, there is a new optimism: Africa is definitely not where it was 50 years ago.3 Many years of capacity-building have increased the number of senior staff in spite of the continued “brain drain”, and globalization of communication has contributed to an increasing democratization and accountability of education and politics. Combined with attitudinal changes in donor countries and institutions,4 there is a stronger awareness of the need to phrase answers to problems in terms of local ability rather than of foreign assistance interests, although problems in “vertical programming” remain.5 While it is too early to judge the sustainability of these political realities, it is time to greatly enhance system support to enable nations and regions in Africa to govern and manage their health sectors. In particular, it is high time to enable Africa to educate its own leaders in public health – those needed to execute essential public health functions, improve system performance and form an African voice for public health.

Project rationale, history and scope

Academic education in the health sciences in Africa tends to follow the models used in the countries that colonized Africa. Medical faculties, now often faculties of health sciences, provide training for medical and paramedical staff concerned with direct patient care. On the other hand, field-level public health workers or laboratory personnel usually train at technical colleges or through in-service courses. Medical scientists and doctoral-level researchers are educated in only a few countries, usually through a combination of practice in research institutions and degree training in African and global universities.

A category of health worker not being adequately catered for is the public health professional, defined in a broad sense as those responsible for providing leadership and expert knowledge to health systems at district, provincial, national and international levels to manage the health of the public. Graduate education in public health is mostly done through departments of community health or community medicine, usually located in faculties of medicine. Access to programmes was – and often still is – open to health professionals only, often only to medical doctors. Starting in the 1970s, some departments became institutes or schools of public health. There was a brief attempt to network these emerging public health institutions to help standardize educational programming with the formation of the Network of African Public Health Institutions (NAPHI)6 in Uganda in 1995, but this did not develop further.

At the AfriHealth project’s start in 2001, there was neither a vision for developing capacity to educate staff to manage health systems and public health, nor plans for educating sufficient personnel to manage and develop health systems in Africa. Medical and health science faculties, business schools and schools of public administration all tended to ignore such concerns. With the exception of a Rockefeller Foundation initiative in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Uganda and Zimbabwe (Public Health Schools Without Walls (PHSWOW)),7,8 little multidisciplinary, system-oriented training in public health was available in Africa. No continent-wide assessment of high-level personnel in public health or academic public health capacity had been done.

Yet the interventions needed to deal with health problems in Africa were becoming ever more “system intensive”.5,9,10 There is an increasing need for a sufficient number of African public health professionals and for plans to educate them to provide expertise and leadership for health systems management, transformation and research. The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) Health Strategy of 2003 called for increased public health training capacity in Africa.11 Yet recent studies focusing on human resource requirements for health1,12,13 do not elaborate on these core personnel to manage and develop health systems.

AfriHealth set out to map advanced public health education capacity in and for Africa and to understand information technology’s roles in enhancing this capacity. First information on education for Africa would allow an estimation of the external funding available and of the institution-building effect that scholarship support could make if more were spent in Africa. As it proved impossible to obtain reliable information about public health education for Africa, this paper cannot report on this issue. Second, understanding the potential of information technology to strengthen continental capacity for public health education is essential given the dispersed nature of public health institutions. This aspect was reported elsewhere.14 This paper, then, presents the first map of university-based public health education capacity in Africa.

Methodology

To guide the project design and implementation both external and local advisory groups were established. The basis for data collection was a questionnaire and interview schedule dealing with coursework, students, staff, facilities, funding and information on international collaboration. A group of African experts fluent in either English, French or Portuguese was convened to administer these questionnaires and interviews. Heads of all departments or schools in Africa were first contacted by telephone and e-mail, and then were sent the questionnaire. This was followed up by telephone contact and personal visits. Completed questionnaires were checked for missing items. Data were collated and analysed using Microsoft Excel and simple descriptive statistics.

Data collection started in November 2001 and continued until June 2003. Provisional reporting was done then, although the data were incomplete. Completion and updating resumed in June 2006 with the help of the School of Public Health at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda.

Information obtained on public health training in several countries indicated that training was given but was not at the level of a master’s degree in public health (MPH) or higher. No information was sought on these countries in the second part of this study. The countries included are:

Burundi was in the process of establishing a National Institute of Health (joint university/ministry of health). No information was sought in the second round of the survey.

Cape Verde had health management training for lusophone countries that it may restart, in collaboration with University Jean Piaget, to train nurses at advanced public health level. No information was sought in the second round of the survey.

Democratic Republic of the Congo: The questionnaire for the first round of the survey was returned for the University of Kinshasa. No information was obtained for Lubumbashi University.

Eritrea had one institution, the University of Asmara. In the second round of the survey, the department was being restructured and could not provide information.

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya: training occurred in medical schools. There are apparently seven departments of community medicine. No information was sought in the second round of survey.

Madagascar offered a postgraduate diploma in public health; started an MPH programme with WHO fellowship support; approximately 30 students. No more information was sought in the second round of survey.

Mauritius had no medical school; Mauritius Institute of Health organizes short courses in reproductive health (three months) and in information technology for health workers.

Niger trained nurses at university level jointly with University of KwaZulu-Natal. No information was sought in the second round of survey.

Togo offered university training for nurses, including in public health.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of university departments of community health and similar institutes and schools in Africa.

Table 1. Countries with postgraduate public health (PH) training programmes.

| Country | Institutions with postgraduate PH programmes | Language (region for north Africa)a | Population (thousands)b | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Algeria | 4 | N | 32 854 | – |

| 2 | Benin | 1 | F | 8 490 | MPH awarded by university; regional course; multilingual planned; WHO-supported. |

| 3 | Cameroon | 1 | Fc | 17 795 | – |

| 4 | Côte d’Ivoire | 1 | F | 18 585 | Offers a 4-year certificate d’étude speciale en sante publique; to see this as more than MPH it must come out of list of no-training. |

| 5 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2 | F | 58 741 | – |

| 6 | Egypt | 13 | N | 72 850 | All departments of PH except Alexandria; there are more than 13 institutions. |

| 7 | Ethiopia | 3 | A | 78 986 | Addis Ababa, Jimma, Gonder. |

| 8 | Ghana | 1 | A | 22 535 | – |

| 9 | Kenya | 6 | A | 35 599 | Moi, Nairobi, Amref, TEACH; MPH in zoology in Kenyatta; Maseno: MPH; Kenya Methodist Univ: MPH. |

| 10 | Malawi | 1 | A | 13 226 | – |

| 11 | Morocco | 4 | N | 30 495 | – |

| 12 | Mozambique | 1 | L | 20 533 | Aimed at Mozambique only; CRDS intends MPH and short courses as well – focusing on epi and health systems. |

| 13 | Nigeria | 11 | A | 141 356 | – |

| 14 | Rwanda | 1 | Ac | 9 234 | MPH, USAID funded through National University of Rwanda. |

| 15 | Senegal | 1 | F | 11 770 | – |

| 16 | South Africa | 8 | A | 47 939 | – |

| 17 | Sudan | 2 | N | 36 900 | – |

| 18 | United Republic of Tanzania | 2 | A | 38 478 | Kilimanjaro Christian Med Coll – MPH; Muhimbili MUSPH. |

| 19 | Tunisia | 6 | N | 10 105 | – |

| 20 | Uganda | 1 | A | 28 947 | Mbarara: began MPH e-learning with Lund University, Sweden in 2005. |

| 21 | Zambia | 1 | A | 11 478 | – |

| 22 | Zimbabwe | 1 | A | 13 120 | – |

| Totals for the 22 countries listed | 72 | – | 760 016 | – | |

| Totals all countries | 53 | – | 922 013 | – | |

CRDS, Centre Regional de Desenvolvimento Sanitario (Mozambique); MPH, master’s in public health; MUSPH, Muhimbili University School of Public Health; TEACH, Tropical Institute of Community Health and Development in Africa. a A, anglophone; F, francophone; H, Hispanic; L, lusophone; N, north Africa. b All numbers used represent medium variant estimates for 2005.20 c Cameroon included with francophone countries; Rwanda with anglophone countries.

Overall, 29/53 countries (54.7%) offer no postgraduate training in public health, 11/53 countries (20.7%) have one programme and 11/53 countries (20.7%) offer more than one programme. If the analysis is stratified by language group, major differentials appear: anglophone sub-Saharan African countries as well as those in north Africa have more developed postgraduate public health training programmes than francophone, lusophone and the one Hispanic country (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of public health education in Africa by language grouping.

| Language group | Countries without public health education programmes | Population in countries without public health education programmes (thousands) | Total population in 2000 | Percentage of total population in countries without public health education programmes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglophone Africaa | 11/20 | 30 330 | 471 228 | 6.4 |

| Francophone Africaa | 18/20 | 106 473 | 221 854 | 48.0 |

| Lusophone Africa | 4/5 | 18 352 | 38 885 | 47.2 |

| North Africa | 2/7 | 6 358 | 189 562 | 3.4 |

| Equatorial Guinea (Hispanic) | 0/1 | 484 | 484 | 100.0 |

| 53 | 922 013 |

a Cameroon is included with Francophone countries; Rwanda with Anglophone countries.

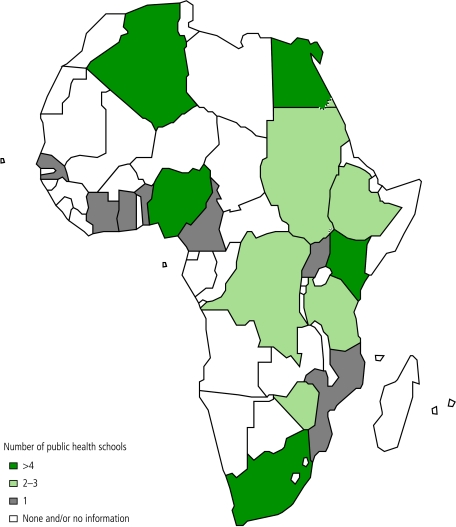

It is obvious that the largest gap occurs in lusophone countries (91% of the population lives in countries without graduate public health programmes) followed by francophone Africa (34%; Fig. 1, Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Mapping Africa’s advanced public health education capacity: the AfriHealth project

In total, there are 854 staff members working in institutions offering postgraduate public health programmes, only 493 of whom work full-time. Male staff is in the majority (63%) and this differential increases if having a doctoral degree is taken into consideration (73%). Viewed in another way, 89.2% of male staff have either a master’s or doctoral qualification, in contrast to only 71.6% of female staff (Table 3, Table 4).

Table 3. Academic staff characteristics: gender and source of salary paymenta.

| Full-time |

Part-time |

Associate |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of institutions | Number of staff | Average staff / institution | Number of institutions | Number of staff | Average staff / institution | Number of institutions | Number of staff | Average staff / institution | |||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 38 | 298 | 7.8 | 36 | 157 | 4.4 | – | – | – | ||

| Female | 37 | 179 | 4.8 | 36 | 86 | 2.4 | – | – | – | ||

| Salary | |||||||||||

| Institution | 38 | 414 | 10.9 | 35 | 126 | 3.6 | 31 | 129 | 4.2 | ||

| External funds | 31 | 79 | 2.5 | 32 | 52 | 1.6 | 31 | 54 | 1.7 | ||

a Staff for whom gender and salary information was not available are not included.

Table 4. Academic staff characteristics: qualifications and age distributiona.

| Male |

Female |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of institutions | Number of staff | Average | Number of institutions | Number of staff | Average | ||

| Qualifications | |||||||

| Doctorate | 40 | 236 | 5.9 | 39 | 86 | 2.2 | |

| Master’s degree | 36 | 151 | 4.2 | 36 | 63 | 1.8 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 33 | 41 | 1.2 | 33 | 41 | 1.2 | |

| No bachelor’s degree | 34 | 6 | 0.2 | 34 | 18 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 434 | 208 | |||||

| Age distribution | |||||||

| < 35 years | 34 | 44 | 1.3 | 35 | 40 | 1.1 | |

| 35–50 | 36 | 261 | 7.3 | 35 | 113 | 3.2 | |

| 51+ | 34 | 78 | 2.3 | 35 | 27 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 383 | 180 | |||||

a Not all information was available for all staff listed; people may hold more than one degree.

The age-distribution of staff skews towards younger age groups: 15% are aged 35 years or younger, 66% are aged between 36 and 50 years, and only 19% is older than 51 years of age. There is therefore a shortfall of senior staff in institutions of public health. This study did not allow an understanding of this dynamic, including whether it relates to migration, illness, internal transfer to better-paying externally funded positions, or to other causes. Finally, there are few foreign staff members working in institutions in Africa: of the 554 staff about whom information was available, 11 (2%) were nationals from other African countries and 40 (7%) were nationals from outside Africa.

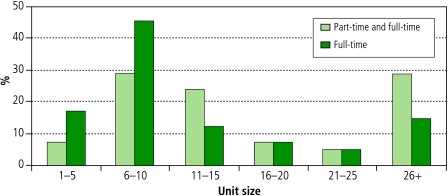

Most institutional units delivering postgraduate public health programmes are small, and rely heavily on part-time staff (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Size of departments and institutions offering graduate public health education

If only full-time staff is considered, over 80% of units delivering postgraduate public health education have 20 staff members or less, and well over 60% have less than 10 staff members. Six large institutions have 26 or more staff members: in Algeria the École Nationale de Santé Publique; in Egypt Menoufiya University; in South Africa the universities of Cape Town and of KwaZulu-Natal; in United Republic of Tanzania the Muhimbili University College of Health Sciences; and Makerere University School of Public Health in Uganda.

Characteristics of postgraduate programmes

Many postgraduate public health programmes remain traditional, with a narrow view of public health, limiting access to health workers or even to medical practitioners only. These characteristics stem from the fact that most graduate public health programmes emerge from departments of community health or community medicine that in the anglophone world tend to be in medical schools, and therefore limit intake to medical practitioners.

Many institutions offer short courses – either on their own, through research and service institutions or with and on behalf of foreign institutions and nongovernmental organizations. Few of these short courses are integrated into degree programmes, creating parallel and unintegrated approaches to postgraduate programmes that further tax scarce human resources.

Distance learning is rare, as are on-the-job and on-campus programmes. Most notably, such programmes are found in the former PHSWOW institutions (Ghana, Uganda, Zimbabwe)3 and in South Africa’s schools of public health.

Few institutions have “north–south” links and even fewer have “south–south” links. The few well-known African institutes and schools of public health have many links – mostly of the former type and mostly in joint research programmes, with joint education being a less frequent reason for collaboration. For all units combined, however, links with either type of institution are uncommon.

Student intake at the postgraduate level is over 1300 a year; as data on student intake in Egypt and Nigeria are incomplete, the total may be somewhat higher. In particular, the number of MPH courses in Africa is increasing rapidly, so the number of students graduating in public health annually is rising. There is much less growth in research degree students and courses (master’s, doctoral or equivalent).

Most programmes target national needs, rather than regional or international requirements. Only three countries, or five institutions, specifically mentioned providing for or recruiting international students. Other institutions may accept external students but train primarily for national needs.

Linking education and research

The questionnaire did not ask specifically about research components of curricula, but it is conventional that all master’s and doctoral students engage in research projects. Institutions that offer postgraduate programmes in public health generally have a low research output, with the exceptions of larger schools and institutions of public health. Research output is much lower than student intake, even counting only students with research degrees. Finally, in institutions where there are productive “centres of research excellence”, postgraduate students do not seem to be engaged in these activities directly.

Conclusions and recommendations

Three limitations should be noted. First, in spite of the follow-up schedule, it was not possible to obtain comprehensive data on all countries. Second, this study could not measure public-health-related training in, for example, tropical diseases research, medical research institutions, nursing schools, social science institutes or business schools due to lack of resources. While it is unlikely that this study will have missed major educational programmes in public health based on this limitation, it may have missed an individual innovative programme. Third, mapping results will inevitably be quickly outdated. Therefore, there will be errors, omissions and inaccuracies in the data presented, but to the extent that such errors might influence the main conclusions and recommendations reached, we believe that the impact is negligible. The actual database is available from the web site of the School of Health Systems and Public Health at the University of Pretoria in a way that allows institutions to correct their data (http://afrihealth.up.ac.za/database/database.htm) or as a spreadsheet file (http://www.cohred.org/AfricaSPH).

There are critical gaps in advanced public health education in Africa. On the continent as a whole, there are 29 countries without graduate public health training and 11 countries with one institution or programme only. Training is done mostly by small units that lack the critical mass needed to expand the field of public health into the multisectoral effort it should be. The greatest shortages occur in lusophone and francophone Africa, and in the one Spanish-speaking country (Equatorial Guinea). There are only 493 full-time faculty in public health for the entire continent (854 if part-time staff are counted as well) and only 42 doctoral students and 55 master’s-level students enrolled for 2005: together, these degrees can be considered to constitute the continent’s public health research training capacity.

The master’s degree in public health (MPH), however, is growing rapidly in anglophone and lusophone Africa. The questionnaire did not allow comparison between programmes, and there may be substantial differences between MPH programmes. Public health research and public health education seem to be separate in all programmes.

As a colleague said about the findings of this study, “the total academic public health workforce in Africa could fit into the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins”. While this may not be factually true, the overwhelming shortage of academic staff in public health in Africa is clear. While there is no clarity about an optimal number, less than 500 full-time academic staff distributed in small groups across Africa are unlikely to deliver the public health leadership needed for nearly one billion people.

At the same time, public health education in Africa is in a dynamic phase. For example, some countries in which there was no previous public health education programming are establishing national institutes of public health that combine research and education. Regional collaboration in graduate programmes is becoming more frequent, as are “south–south” collaborations, and there are other developments. The study could not systematically measure future trends but the overall impressions are that public health is in a revival mode in some parts of Africa and that this can be built on for the continent as a whole.

Where to from here?

Africa needs a plan for public health human resources that can become an explicit part of WHO’s Human Resources for Health programme, of the agenda of the Global Health Workforce Alliance, of NEPAD and of the African Union. African institutions and external partners and ministries of health should engage by conducting relevant assessments nationally and regionally. Developed countries, whether partnering for financial assistance or for technical support, must make institutional capacity development a core objective. Part of preparing a plan for Africa should be an attempt to quantify the competencies and numbers of trained staff needed, so that African and other institutions can target their educational programmes better and avoid duplications and gaps.

The lack of critical mass in African public health is compounded by the small size of these postgraduate public health programmes: over 80% have 20 or fewer staff members. Priority interventions to strengthen public health education would include: first, supporting existing centres and creating new centres in public health practice; research and education with sufficient professional capability for multidisciplinary work; and innovation to develop African solutions to public health problems. Selection of sites for such centres could be done on the basis of language groupings, geographical distribution or the possibility of attaching such centres to existing “centres of excellence” in public health research. The concept of centres of excellence is sometimes seen as problematic, as these could increase inequities between countries. On the other hand, the recent Leadership Initiative for Public Health in east Africa illustrates that centres of excellence can be shared and can have a wider, subregional influence.15 An added benefit of larger centres may be that they are able to attract African expatriates in a way that the many small units cannot. There is also a need to increase the proportion of research degree students at both master’s and doctoral levels,2 and larger centres offer more conducive environments for research.

Second, an investment in distance learning technology, educational as well as technical, can assist greatly in optimizing use of existing resources.14

In the short term, access to the many disciplines that a wider public health education programme requires can be enhanced by flexible enrolment in existing programmes across faculties and universities. Academic institutions, faculties and departments can arrange coursework in more modular formats that allow students to take training in different departments and universities, even in different countries. This will make courses more multi-disciplinary and encourage standardization and benchmarking of public health education. The European Credit Transfer System may offer an example of how this could be done.16 Regional groupings such as the East African Association of Public Health could spearhead such arrangements rather than attempts to do this at a pan-African level. This would also be in line with the efforts of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to increase educational standardization and exchange between countries on the continent.17 Easier credit transfer systems give students increased control over their education, increase diversity of learning and will help in quality control through standardization and benchmarking. However, on its own, credit transfer is not sufficient and is complex to implement, and should probably be considered a medium-term goal.

For public health to grow as a discipline, increase its impact and take on its potential role as a voice for health in Africa, it is essential to internationalize training, to open up to new students outside the health sector and to new academic partners so that many more sectors find a home in schools of public health. Linking public health research to public health education is essential to increase interaction between evidence and practice.

Support for the transformations needed in postgraduate education across the continent can be provided by an effective Association of Schools of Public Health for Africa. This can support standardization, accreditation, benchmarking and capacity-building; it can support efforts for institutional change; it can negotiate partnerships and seek additional resources; it can align institutional priorities and help create a voice for public health in Africa.

Funding for this will have to come from external sources to help boost the current positive climate in public health. Besides direct support, funding can be increased by conducting as much as possible of public health training in Africa, so that scholarships start contributing to building African institutions. Programmes that prepare for system-intensive interventions need to invest in health system management disciplines, epidemiology, and monitoring and evaluation, and should do this in African schools of public health. Foundations, donors and international aid agencies interested in improving health in Africa in a sustainable manner should consider that schools of public health – in the widest multidisciplinary sense – are key in building the disciplines needed for sustainable health development and health equity. Fortunately, there is a growing interest in some bilateral aid agencies in supporting public health leadership building15,18 and there is also an increase in charitable funding with the entry of new foundations.19 Hopefully, these initiatives will be followed by others. ■

Acknowledgements

The authors want to express their sincere appreciation for the support, advice and comments on this project to the following persons who have been involved with the AfriHealth project, without whom this work could not have been completed: Abdallah Bchir (Tunisia), Robert Beaglehole (New Zealand), Eric Buch (South Africa), Tim Evans (USA), Paulo Ferrinho (Portugal), Hassen Ghannem (Tunisia), Wade Hanna (USA), Marian Jacobs (South Africa), Fadel Kane (Senegal, Canada), Bob Lawrence (USA), Adetokunbo Lucas (Nigeria), Reginald Matchaba-Hove (Zimbabwe), Bronwyn Moffet (South Africa), David Mowat (Canada), Mutuma Mugambi (Kenya), Mary Mwaka (Kenya, South Africa), Vic Neufeld (Canada), Samuel Ofosu-Amaah (Ghana), Augusto Paulo Silva (Guinea-Bissau), Anne Strehler (South Africa), KR Thankappan (India), Steven Tollman (South Africa), Jeroen van Ginneken (Netherlands) and Fred Wabwire-Mangen (Uganda). The first author acknowledges support from SARETI at University of KwaZulu-Natal, where he is an adjunct professor in the School of Psychology. We are also grateful to the Rockefeller Foundation and New York University for providing the funding for the original project (2001) and for the completion phase (2006–2007), and to the School of Health Systems and Public Health at the University of Pretoria for making the access to this information more user-friendly. The database can be downloaded from http://www.cohred.org/AfricaSPH.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Working together for health Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- 2.IJsselmuiden C. Human resources for health research. Medicus Mundi Bulletin 2007;104:22-7. Available at: http://www.medicusmundi.ch/mms/services/bulletin/bulletin104_2007/chapter0705168999/bulletinarticle0705164414.html

- 3.Volmink J, Dare L, Clark J. A theme issue “by, for, and about” Africa. BMJ. 2005;330:684. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7493.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. 2 March 2005. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/11/41/34428351.pdf

- 5.Garrett L.The challenge of global health. Foreign Aff 200786Available athttp://www.foreignaffairs.org/20070101faessay86103/laurie-garrett/the-challenge-of-global-health.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Network of African Public Health Institutions. New Orleans: Tulane University. Available at: http://www.tulane.edu/~phswow/Naphi.htm

- 7.Beaglehole R, Dal Poz MR.Public health workforce: challenges and policy issues. Hum Resour Health 200314Available athttp://www.human-resources-health.com/content/1/1/4 10.1186/1478-4491-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Schools Without Walls. Available at: http://www.tulane.edu/~phswow/index.htm

- 9.Health systems: improving performance Geneva: WHO; 2000.

- 10.International Development Research Centre. Fixing health systems. 5. Lessons learned. Available at: http://www.idrc.ca/en/ev-64764-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html

- 11.NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa’s Development). Health Strategy, September2003. Initial Programme of Action, pp. 9-10.

- 12.World Health Organization. African Health Workforce Observatory. Definitions of the 23 Health Workforce Categories. Available at: http://www.who.int/globalatlas/docs/HRH_HWO/HTML/Dftn.htm

- 13.Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health – overcoming the crisis. Rockefeller Foundation, 2004. ISBN 0-9741108-7-6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strehler A. Mapping the capacity for technology-supported and technology-based distance learning in public health education in and for Africa Available at: http://afrihealth.up.ac.za/reports/Afrihealth_nov2002.PDF

- 15.Leadership Initiative for Public Health in East Africa. Available at: www.liphea.org

- 16.European Credit Transfer and Accummulation System – ECTS. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/education/programmes/socrates/ects/index_en.html

- 17.UNESCO. Regional convention on the recognition of studies, certificates, diplomas, degrees and other academic qualifications in higher education in the African states. Adopted at Arusha on 5 December 1981, revised at Cape Town on 12 June 2002, and amended in Dakar on 11June2003. Available at: http://www.dakar.unesco.org/pdf/031205_arusha_en.pdf

- 18.Crisp N. Global Health Partnerships. The UK contribution to health in developing countries. Report to the UK government, February 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_065374

- 19.African Health Initiative. Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Available at: http://www.ddcf.org/page.asp?pageId=720

- 20.Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. World population prospects: the 2006 revision. Highlights. New York: United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]