Abstract

Objective

Trials of environmental risk factors and acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) face a double challenge: implementing sufficiently sensitive and specific outcome assessments, and blinding. We evaluate methods used in the first randomized exposure study of pollution indoors and respiratory effects (RESPIRE): a controlled trial testing the impact of reduced indoor air pollution on ALRI, conducted among children ≤ 18 months in rural Guatemala.

Methods

Case-finding used weekly home visits by fieldworkers trained in integrated management of childhood illness methods to detect ALRI signs such as fast breathing. Blindness was maintained by referring cases to study physicians working from community centres. Investigations included oxygen saturation (SaO2), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) antigen test and chest X-ray (CXR).

Findings

Fieldworkers referred > 90% of children meeting ALRI criteria, of whom about 70% attended a physician. Referrals for cough without respiratory signs and self-referrals contributed 19.0% and 17.9% of physician-diagnosed ALRI cases respectively. Intervention group attendance following ALRI referral was 7% higher than controls, a trend also seen in compliance with RSV tests and CXR. There was no evidence of bias by intervention status in fieldworker classification or physician diagnosis. Incidence of fieldworker ALRI (1.12 episodes/child/year) is consistent with high sensitivity and low specificity; incidence of physician-diagnosed ALRI (0.44 episodes/child/year) is consistent with comparable studies.

Conclusion

The combination of case-finding methods achieved good sensitivity and specificity, but intervention cases had greater likelihood of reaching the physician and being investigated. There was no evidence of bias in fieldworkers’ classifications despite lack of concealment at home visits. Pulse oximetry offers practical, objective severity assessment for field studies of ALRI.

Résumé

Objectif

Les études de l’influence de facteurs environnementaux sur les infections aigues des voies respiratoires basses (ALRI) se heurtent à une double difficulté, à savoir la mise en œuvre de méthodes d’évaluation des résultats suffisamment sensibles et spécifiques et le masquage des identités. Nous avons donc évalué les méthodes utilisées dans la première étude d’exposition randomisée des effets sur les voies respiratoires de la pollution intérieure RESPIRE (étude cas-témoins randomisée de l’impact d’une réduction de la pollution de l’air intérieur sur les infections aigues des voies respiratoires basses, menée sur des enfants de 18 mois au plus, en milieu rural au Guatemala).

Méthodes

Pour dépister ces maladies, on a eu recours à des visites à domicile par des agents de terrain formés aux méthodes de prise en charge intégrée des maladies de l’enfance permettant d’en détecter les signes, comme l’accélération du rythme respiratoire par exemple. La confidentialité a été maintenue en orientant les cas vers des médecins de l’étude travaillant dans des centres communautaires. Parmi les examens pratiqués figuraient notamment la détermination de la saturation artérielle en oxygène (SaO2), un test de détection antigénique du virus respiratoire syncytial (VRS) et une radiographie thoracique.

Résultats

Les agents de terrain ont orienté vers un spécialiste plus de 90% des enfants remplissant les critères de présence d’une ALRI, parmi lesquels 70% ont consulté un médecin. Les orientations vers un spécialiste pour toux sans signe respiratoire et les consultations de spécialiste à l’initiative des sujets eux-mêmes ont représenté respectivement 19,0% et 17,9% des cas d’ALRI médicalement diagnostiqués. Les membres du groupe d’intervention étaient plus nombreux que les témoins (+ 7%) à suivre la recommandation de consulter un spécialiste pour suspicion d’ALRI, tendance également observée dans la soumission au test de dépistage du VRS et à la radiographie thoracique. On n’a relevé aucun élément indiquant la présence d’un biais lié à la participation du sujet à l’intervention dans la classification par les agents de terrain ou le diagnostic par les médecins. L’incidence des ALRI détectées par des agents de terrain (1,12 épisode/enfant/an) était cohérente avec la forte sensibilité et la faible spécificité de cette méthode de dépistage. Celle des cas d’ALRI diagnostiqués par des médecins (0,44 épisode/enfant/an) était également cohérente avec celle obtenue dans des études comparables.

Conclusion

L’association des deux méthodes de dépistage a permis d’obtenir une sensibilité et une spécificité satisfaisantes, mais la probabilité d’être vu par un médecin et d’être examiné était plus forte pour les cas ayant bénéficié de l’intervention. Aucun élément n’indiquait la présence d’un biais dans la classification établie par les agents de terrain, en dépit du manque de confidentialité des visites à domicile. La sphygmo-oxymétrie offre un moyen pratique et objectif pour évaluer la gravité de la pathologie dans le cadre des études sur le terrain des ALRI.

Resumen

Objetivo

Los ensayos sobre los factores de riesgo ambientales y las infecciones agudas de las vías respiratorias inferiores (IAVRI) encaran un doble reto: la necesidad de implementar evaluaciones de resultados suficientemente sensibles y específicas, y la aplicación de métodos de enmascaramiento. Evaluamos los métodos utilizados en el primer estudio aleatorizado de la exposición a la contaminación del aire en interiores y sus efectos respiratorios (RESPIRE), un ensayo controlado realizado entre niños ≤ 18 meses en zonas rurales de Guatemala para determinar el impacto de la reducción de ese tipo de contaminación en las IAVRI.

Métodos

La localización de casos se hizo mediante visitas domiciliarias semanales realizadas por agentes sobre el terreno adiestrados en los métodos de la atención integrada a las enfermedades prevalentes de la infancia para detectar los signos de IAVRI, como por ejemplo una respiración rápida. El enmascaramiento se logró derivando los casos a médicos que trabajaban en centros comunitarios. Como parte del estudio se determinaron la saturación de oxígeno (SaO2) y la presencia del virus sincitial respiratorio (VSR) y se hizo una radiografía de tórax (RXT).

Resultados

Los trabajadores sobre el terreno derivaron a más del 90% de los niños que cumplían los criterios de IAVRI, alrededor del 70% de los cuales fueron llevados al médico. Las derivaciones por tos sin signos respiratorios y las autoderivaciones representaron el 19,0% y el 17,9% de los casos de IAVRI diagnosticados por los médicos, respectivamente. Las visitas al médico en el grupo de intervención fueron un 7% más frecuentes que en el grupo de control, tendencia observada también en la realización de las pruebas del VSR y la RXT. No hubo ningún dato que indicara un posible sesgo por estado de intervención en la clasificación de los trabajadores sobre el terreno o el diagnóstico de los médicos. La incidencia de IAVRI basada en las evaluaciones de los trabajadores sobre el terreno (1,12 episodios/niño/año) refleja una alta sensibilidad y una baja especificidad; la incidencia de IAVRI diagnosticadas por los médicos (0,44 episodios/niño/año) es similar a la de otros estudios comparables.

Conclusión

La combinación de métodos de búsqueda de casos permitió conseguir una buena sensibilidad y especificidad, pero los casos del grupo de intervención tenían más probabilidades de llegar al médico y ser estudiados. No se observó ningún indicio de sesgo en las clasificaciones de los trabajadores sobre el terreno pese a la falta de ocultación en las visitas domiciliarias. La oximetría de pulso permite evaluar de forma práctica y objetiva la gravedad del estado en los estudios de campo de las IAVRI.

ملخص

الەدف

تواجە الدراسات حول عوامل الاختطار البيئية والعدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة تحديات مزدوجة؛ أولاەا تنفيذ تقيـيمات ذات حساسية ونوعية كافية للحصائل، وثانيەا التعمية. وقد قيَّمنا الطرق التي استخدمت في الدراسة المعشاة الأولى للتعرُّض للتلوث داخل المنازل وتأثيراتە التنفسية، وەي دراسة مُضبَّطة بالشواەد لتأثير إنقاص تلوث الەواء داخل المنازل على العدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة والتي أجريـت علـى الأطفـال الذيـن تقـل أعمارەـم عـن 18 شەراً في أرياف غواتيمالا.

الطريقة

استخدمنا في كشف الحالات زيارات منزلية أسبوعية يقوم بەا عاملون ميدانيون مدرَّبون على الطرق المتبعة في التدبير المتكامل لأمراض الأطفال لكشف علامات العدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة مثل تسرع التنفس. وقد حافظنا على التعمية بإحالة الحالات للأطباء المشاركين في الدراسة الذين يعملون في مراكز مجتمعية. وقد تضمنت الاستقصاءات إشباع الأكسجين، واختبار مستضد الفيروس التنفسي المخلوي وصورة الصدر الشعاعية.

الموجودات

أحال العاملون الميدانيون أكثر من 90% من الأطفال الذين تتوافر لديەم معايـير العدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة، وكان 70% منەم قد راجع طبيباً. وقد تضمنت الإحالات السعال بدون علامات تنفسية في 19% والإحالة الذاتية في 17.9% من حالات العدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة التي شخصەا الأطباء، فيما زادت مراجعة المجموعة التي تلقت التدخل تلو إحالة أفرادەا لإصابتەم بالعدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة عن مثيلتەا من الشواەد بمقدار 7%. وقد شوەد ەذا الاتجاە أيضاً متماشياً مع نتائج اختبار مستضد الفيروس التنفسي المخلوي ومع نتائج الصور الشعاعية. ولم يكن ەناك من البيِّنات على وجود تَحيُّز في وضع التدخلات من حيث ما قام بە العاملون الميدانيون من تصنيف أو تشخيص. ويتماشى معدل حدوث العدوى التنفسية الحادة السفلية الذي كشفە العاملون الميدانيون (ويقدر بـ 1.12 ەجمة/طفل/سنة) مع حساسية مرتفعة ونوعية منخفضة. كما يتماشى معدل حدوث العدوى التنفسية السفلية الحادة التي شخصەا الأطباء مع الدراسات القابلة للمقارنة.

الاستنتاج

أدى الترافق بين طرق كشف الحالات إلى حساسية ونوعية جَيِّدَتَيْن. إلا أن الحالات التي تلقت التدخل كان لديەا احتمال أكبر للوصول إلى الطبيب وإجراء الاستقصاءات. ولم يكن ەناك من البيِّنات ما يدل على تحيُّز لدى العاملين الميدانيـين في تصنيفەم رغم عدم إخفاء زياراتەم المنزلية. ويقدم قياس حدة النبض تقيـيماً عملياً وموضوعياً في الدراسة الميدانية لوخامة العدوى التنفسية الحادة السفلية.

Introduction

Acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) are the single most important cause of death of children under 5 years, responsible annually for approximately 20% of the 10 million under-5 deaths globally.1,2 Prevention strategies are required urgently, including control of risk factors. A growing body of evidence links household indoor air pollution from solid fuels with ALRI in developing countries: recent estimates suggest this may be responsible for nearly one million child ALRI deaths.3 However, these figures are based on relatively few observational studies with considerable variation in ALRI case-finding methods, indirect exposure assessment (using proxies such as fuel type) and risk of residual confounding.4 To address these limitations we conducted a community-based randomized controlled trial with improved chimney stoves in rural Guatemala.

Weaknesses in previous ALRI field studies, and the methodological issues common to trials of environmental interventions, highlighted three particular challenges for this study:

1. To ensure that few cases are missed. Frequent home visits by staff trained to recognize signs such as fast breathing can achieve high sensitivity for ALRI.5 It has been suggested that early treatment associated with more frequent visits may reduce cases of severe ALRI, but a recent review found no evidence of association between surveillance interval (less than 2 weeks) and incidence.1,5

2. To ensure high specificity, as ALRI constitutes a minority (~10%) of all acute respiratory infections. Any impact of reduced exposure on ALRI incidence may be missed if ALRI cases are classified mistakenly with larger numbers of acute upper respiratory infections (AURI). To achieve specificity, all cases identified by fieldworkers should undergo physician examination and preferably chest X-ray (CXR).5

3. To take measures to make physicians’ assessments blind and incorporate objective outcome assessments, as it was not possible for subjects or staff visiting homes to be blind to their intervention status.

This report’s objectives are to describe these methods, evaluate the effectiveness of case-finding and identify any evidence of bias by intervention status. Analysis was carried out using Stata version 9.1.6 An annual ethical review was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the institutional review boards of the Universities of California (Berkeley), del Valle de Guatemala and Liverpool (UK).

Methods

Study area and population

Following extensive feasibility studies,7–13 a rural area of San Marcos in western Guatemala was selected. The indigenous population speaks mainly a Mayan language, Mam, and some Spanish. Wood is the main household fuel, burned indoors on open fires. Key features of the study area are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Study site and population informationa.

| Altitude | Mean 2600 m (range 2200 to 3000) |

| Seasons | Warm and wet: May to October |

| Dry and cold: November to February | |

| Dry and warmer: March to April | |

| Temperature | Average daily temperatures 10.3–12.7 °C. Occasionally below freezing at night during coldest months, producing demand for space-heating |

| Rainfall | Up to 36 mm/day during wet season; almost none December–April |

| Other major diseases that may be confused with ALRI | Malaria is not endemic; few reports of identified cases of HIV and TB |

| Low birth weight | Reported to be 14% prevalence in Guatemala,30 but estimated at 20% in neighbouring Quetzaltenango31 |

| Breastfeeding | Almost universal. Exclusive breastfeeding of children < 4 months reported by 94% of study sample |

| Nutritional status | Area characterized by severe undernutrition. By 17 months, average height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores for study children were 3 standard deviations below normalb |

| Vaccination | Of 95 study children between 2 and 4 months at recruitment, 77 (81%) had received Bacille Calmette–Guérin, 45 (47%) had received DPT/Polio-1 |

ALRI, acute lower respiratory infections; TB, tuberculosis a This information conforms with the minimum data set proposed by Lanata et al.5 Little reliable information is available from external sources, and data from the current study are provided where relevant. b Thompson L. Unpublished data, 2006.

Study design and ALRI case-finding

The study design was a randomized controlled trial comparing ALRI incidence in children ≤ 18 months using the traditional three-stone fire (controls), with intervention homes using a flued wood stove (plancha):7,14 534 homes with either children under 4 months or a pregnant woman were randomized, and planchas constructed in 269. Sample size was determined to detect a 25% change in ALRI incidence of 0.5 episodes per child per year, at 5% significance, 80% power. Surveillance began after 5 weeks when the planchas were ready, from which time 518 children were followed until the age of 18 months, withdrawal or death. ALRI case-finding was carried out at four levels:

Weekly household visits by fieldworkers trained in WHO integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) methods.15

Study physicians, working in local community centres to maintain blindness, undertook clinical assessments of children referred by fieldworkers, or self-referred.

Extraction of information from hospital records.

Verbal autopsy to investigate all deaths.16

Household visits

Weekly home visits ran from December 2002 to December 2004. Each home was visited on the same day every week. If unavailable, one repeat visit was made on the Friday of the same week. From a total of 21 fieldworkers, 16 were recruited from local community leaders, midwives and health promoters; 14 of these were bilingual (Mam-Spanish) and eight (50%) were female. Fieldworkers were allocated equal numbers of plancha and control homes to visit each day.

The fieldworkers’ questionnaire was based closely on IMCI criteria15 and focus groups identified appropriate Mam terms. All fieldworkers underwent one-week IMCI training in symptom and sign recognition (including video for wheeze and stridor), and classification of children as well, sick but suitable for home treatment or requiring referral to study physician. Respiratory rate was measured over one minute using a timer (UNICEF) and repeated when over 60 in children < 2 months (repeat used).

One supervisor carried out repeat home visit assessments in 10% of homes, while a second supervisor directly observed 10% of home visits. Most repeat assessments agreed with the original findings but the child was re-examined when there were disagreements. All forms were reviewed after each day of fieldwork to identify and correct errors.

Not all weekly scheduled visits could be realized, mostly due to internal migration (Table 2). Although there was a slightly lower rate of completed visits to plancha homes, there were similar numbers of realized visits per child, children with no missed visits and dropouts.

Table 2. Possible and completed weekly visits for intervention and control groups.

| Weekly visits | Intervention | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participating children | 265 | 253 | |

| Weekly visits | Total possible in follow-up period | 16 446 | 15 664 |

| Completed | 14 756 | 14 369 | |

| Possible weekly visits completed (%) | 89.7% | 91.7%a | |

| Mean (SD, range) weekly visits per child | 55.7 (17.8; 1–80) | 56.8 (17.3; 2–81)b | |

| Children with no missed visits (%) | 17 (6.4%) | 19 (7.5%)b | |

| Withdrawals | 19 (7.2%) | 14 (5.5%)b | |

NS, non-significant; SD, standard deviation. a P < 0.001 b NS.

A critical indicator of potential bias was how well fieldworkers adhered to the referral algorithm, by intervention status. No child with specific respiratory signs (raised respiratory rate, chest wall indrawing, stridor or wheezing) was classified as well, but approximately 8% (7.9% plancha, 8.8% control) of cases with raised respiratory rates were not referred, with similar findings for other respiratory signs. All non-referrals with fieldworker-assessed fast breathing had respiratory rates in the ranges considered normal for the next youngest age group (Table 3),15 suggesting that non-referral resulted from uncertainty about ages and thresholds for rapid breathing. Most of these referrals (81%) occurred in the first half of the study.

Table 3. Mean respiratory rate per minute (and distributions) for children with respiratory illness with fieldworker-measured raised respiratory rate.

| Age group | n | Referred to doctor | Mean (SD) | Geometric mean | Range | 25th–75th percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to < 12 months | 202 | Yes | 56.3 (6.5) | 55.9 | 50–88 | 52–59 | MW: P = 0.09 t-testa: P = 0.11 |

| 10 | No | 53.1 (3.2) | 53.0 | 50–58 | 50–56 | ||

| ≥ 12 months | 291 | Yes | 48.7 (7.0) | 48.3 | 40–89 | 44–52 | MW: P < 0.0001 t-testa: P < 0.0001 |

| 32 | No | 43.9 (2.9) | 43.8 | 40–49 | 42–46.5 |

MW, Mann–Whitney test; SD, standard deviation. a t-test on log transformed respiratory rate.

Fieldworker-assessed symptoms and signs were combined to produce four definitions of new ALRI cases (Table 4): 668 cases met the criteria for lower respiratory illness, plus stridor, a rate of 1.12 (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.03–1.20) episodes per child per year. No cases were classified as well, but 8.9% and 9.3% were classified as unwell and suitable for home treatment in plancha and control groups respectively.

Table 4. Compliance with classification algorithms for fieldworker-assessed categories of new episodes of ALRI, and with referral to the study physiciansa.

| Stage in referral process | Possible pneumoniab (n = 540) |

Wheezing illnessc (n = 114) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plancha | Control | P-value | Plancha | Control | P-value | ||

| Of those meeting outcome criteria: | |||||||

| • Classified by FW as “well” | 0 | 0 | 0.61 | 0 | 0 | 0.61 | |

| • Classified by FW as “unwell” but for home treatment | 9.3 | 8.1 | 14.6 | 18.2 | |||

| • Classified by FW as “unwell” and referred to physician | 90.7 | 91.9 | 85.4 | 81.8 | |||

| Attended physician before next home visit, as % of cases meeting criteria | 72.5 | 70.1 | 0.53 | 71.2 | 58.3 | 0.14 | |

| Attended physician before next home visit, as % of cases referred by FW to physician | 79.4 | 75.9 | 0.33 | 82.2 | 72.2 | 0.24 | |

| Physician visit same day or later same week, as % of cases meeting criteria |

69.0 |

64.3 |

0.25 |

60.4 |

43.9 |

0.08 |

|

| Stage in referral process |

Lower respiratory illnessd

(n = 637) |

Lower respiratory illness,

plus stridore (n = 668) |

|||||

|

Plancha |

Control |

P-value |

Plancha |

Control |

P-value |

||

| Of those meeting outcome criteria: | |||||||

| • Classified by FW as “well” | 0 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 0 | 0.88 | |

| • Classified by FW as “unwell” but for home treatment | 9.6 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 9.3 | |||

| • Classified by FW as “unwell” and referred to physician | 90.4 | 90.5 | 91.1 | 90.7 | |||

| Attended physician before next home visit, as % of cases meeting criteria | 72.3 | 67.8 | 0.2 | 71.6 | 67.1 | 0.18 | |

| Attended physician before next home visit, as % of cases referred by FW to physician | 79.8 | 75.3 | 0.17 | 78.7 | 74.3 | 0.17 | |

| Physician visit same day or later same week, as % of cases meeting criteria | 68.6 | 61.9 | 0.07 | 68.8 | 62.2 | 0.07 | |

ALRI, acute lower respiratory infections; FW, fieldworker. a All figures (other than total numbers of cases meeting criteria and P-values) are percentages within study arms. Definitions of ALRI health outcomes are based on fieldworker assessment at home visits. b Children less than 2 months of age with any of: raised respiratory rate (> 60/minute), nasal flaring, grunting or chest wall indrawing. Children aged 2 months or more with cough or difficulty breathing and any of: increased respiratory rate (> 50 for children 2 months to less than 12 months; > 40 for children 12 months or over) or lower chest wall indrawing. Stridor is not included. These children may or may not have wheeze as heard without auscultation by the fieldworker. c For child less than 2 months, FW reported audible wheeze on examination. For child aged 2 months or older wheezing disease was defined as a child having a cough or difficulty breathing and FW reported audible wheeze. These children do not have any of the above signs meeting criteria for possible pneumonia. d Possible pneumonia and/or wheezing illness, using definitions above. e Using definition (d) above, but including fieldworker reported stridor.

Severe fieldworker-assessed cases (severe WHO pneumonia) were defined as new cases (including nine with non-severe ALRI the previous week) of lower respiratory illness, plus stridor, with chest indrawing and/or inability to drink or breastfeed. There were 72 of these cases, a rate of 0.12 (95% CI: 0.09–0.15) episodes per child per year.

It was expected that not all referred sick children would be taken to the study physician. Almost 80% of referrals for possible ALRI attended the physician before the next weekly visit (Table 4), consistently 3–5% higher in the plancha group (NS). About 70% of all children meeting referral criteria attended the physician before the next weekly visit, 5% more in the plancha group (NS).

Approximately two-thirds of all children with ALRI criteria completed consultations on the day of referral if referred or later that week (Table 4), 5–7% higher in the plancha group (16% for cases with wheeze only), 0.05 < P < 0.1 for outcomes including wheeze. Nearly all (96%) of plancha children referred with severe WHO pneumonia attended the physician, compared to 73% of controls (Fisher’s exact P = 0.02). For 295 visits where a child had ALRI signs but did not see the physician that week, 48 (16.3%) had signs of ALRI at the following weekly visit and 7 of these had severe WHO pneumonia; all 7 were in the control group (P = 0.03).

Fieldworkers also referred 1212 episodes of cough or difficulty breathing, but no specific respiratory sign: 842 (69.5%) attended, and 49 (5.8%) were diagnosed with pneumonia.

Clinical assessment by study physicians

Study physicians assessed children in community centres located up to 1 km from their homes. A standardized history and examination was developed from earlier studies.17,18 Training sessions were held every one to two months at San Marcos Hospital in order to maintain consistent interpretation of clinical signs – each physician assessed children independently, then compared findings with other physicians and the resident paediatrician.

Six Guatemalan physicians were employed during the study: one (SO) worked almost throughout and four carried out the majority (94.6%) of consultations. A total of 1991 consultations among 467 study children were completed for illnesses other than minor skin and eye conditions (recorded separately). Five respiratory diagnoses were used: AURI; otitis media; laryngo-tracheo-bronchitis; pneumonia; and wheezing illness. Pneumonia was categorized as none, possible or definite, based on the physician’s clinical judgment, and new cases were defined as those following at least one weekly home visit without ALRI signs. With the exception of wheezing illness, respiratory diagnoses usually were applied exclusively (Table 5).

Table 5. Co-morbidity in terms of respiratory diagnoses by study physicians (for 263 cases diagnosed).

| Other diagnoses | Presence or absence | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia per diagnostic category: number (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Possible | Definite | ||||||

| AURI | Present | 885 | (51.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | – | |

| Absent | 841 | (48.7) | 207 | (99.5) | 55 | (100) | ||

| Otitis media | Present | 105 | (6.1) | 3 | (1.4) | 0 | – | |

| Absent | 1621 | (93.9) | 205 | (98.6) | 55 | (100) | ||

| LTB (croup) | Present | 6 | (0.3) | 0 | – | 0 | – | |

| Absent | 1720 | (99.7) | 208 | (100) | 55 | (100) | ||

| Wheezing illness | Present | 23 | (1.3) | 48 | (23.1) | 10 | (18.2) | |

| Absent | 1703 | (98.7) | 160 | (76.9) | 45 | (81.8) | ||

AURI, acute upper respiratory infections; LTB, laryngo-tracheo bronchitis.

Physicians recorded 263 new episodes of pneumonia, a rate of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.39–0.49) episodes per child per year: 216 (82%) from fieldworker referrals, 47 (18%) from self-referrals. The incidence of fieldworker-assessed AURI was 3.44 episodes per child per year based on current respiratory symptoms, and 5.96 when “symptoms since last visit but now resolved” are included, thus between 7.8 and 13.5 times the physician-diagnosed pneumonia rate.

Intervention and control groups reported similar signs used in pneumonia diagnosis, apart from crepitations (Table 6). Using physician-diagnosed pneumonia as the reference, a raised respiratory rate had moderate sensitivity, but poor specificity and positive predictive value (PPV). Chest wall indrawing was recorded in 36% of pneumonia cases but few other cases so while sensitivity was low, specificity and PPV were high. Crepitations were recorded in well over 80% of pneumonias, and in almost no other diagnoses, thus having high sensitivity, specificity and PPV. A lower proportion of intervention pneumonia cases had crepitations recorded (P = 0.02).

Table 6. Total cases seen by study physicians, and recording of key respiratory signs in making diagnoses of (a) pneumonia and (b) all other cases for intervention (I) and control (C) groupsa.

| Physician | Total cases seen by physicianb | Cases with rapid breathing (%) |

Cases with chest indrawing (%) |

Cases with crepitations (%) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia |

Other illness |

Pneumonia |

Other illness |

Pneumonia |

Other illness |

||||||||||

| I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | ||||

| SO | 837 (42.1%) | 73 | 74 | 22 | 17 | 34 | 18 | – | – | 94 | 97 | – | – | ||

| EO | 476 (23.9%) | 60 | 32 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 9 | – | 0.5 | 86 | 94 | – | 0.5 | ||

| AJ | 378 (19.0%) | 61 | 81 | 18 | 18 | 48 | 72 | – | 0.7 | 76 | 84 | – | – | ||

| DJ | 192 (9.7%) | 74 | 92 | 55 | 39 | 52 | 50 | 6.5 | – | 74 | 83 | – | – | ||

| Other | 107 (5.4%) | 83 | 80 | 32 | 22 | 41 | 40 | 2.7 | – | 67 | 90 | 2.7 | 3.1 | ||

|

All |

1990 |

70 |

69 |

22 |

17 |

36 |

39 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

81 |

91 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

||

| P-valuec | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.27 | |||||||||

FW, fieldworker; AJ, DJ, EO, and SO, initials of physicians. a A total of 1991 cases were seen, but MD identification is missing for one. Apart from total cases seen (column 2), all figures are percentages of cases within study groups. b Total cases refers to all potentially serious and respiratory conditions. All minor conditions such as rashes and conjunctivitis in an otherwise well child were recorded separately. c χ² test for intervention versus control comparisons, for all cases (last row).

Fieldworker classifications were compared against physician diagnoses: only 5.8% of referrals with cough or difficulty breathing but no specific lower respiratory signs were diagnosed with pneumonia, compared to 28.1% of non-severe ALRI referrals and 47.3% of severe ALRI referrals (P < 0.001).

Pulse oximetry

Low oxygen saturation is a complication of ALRI associated with increased mortality.19,20 Study physicians used pulse oximetry to measure oxygen saturation (SaO2) in all consultations. A Sims BCI Mini Corr was used initially, left on the foot for two to three minutes until the reading was stable. From November 2003, Nellcor N-20 oximeters were used. These were more reliable with distressed children, taking six readings on the foot at 30-second intervals (mean used).

To obtain typical SaO2 levels at the study altitude (Table 1), 55 randomly selected study children were investigated by using the Nellcor N-20 and recording whether or not the child was well (reported by mother). Well children had mean SaO2 of 93.2% (standard deviation, SD 3.0; 95% CI: 92.7–93.7), median 93.5% and range 82% to 98% (Table 7), consistent with other studies.19 Hypoxaemic pneumonia cases will be defined as SaO2 > 2 SD below the mean for well children19: for this study, 93.2% – (2×3.0) = 87.2% (rounded to 87%).

Table 7. SaO2 data from pulse oximetry study of well children (n = 55).

| Diagnostic group | Number of measurements | Mean (SD) | Median | Minimum | Maximum | 25th–75th centile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children reported “well” by mother/carer | 128 | 93.2 (3.0) | 93.5 | 82 | 98 | 91.4–95.4 |

SaO2, oxygen saturation; SD, standard deviation.

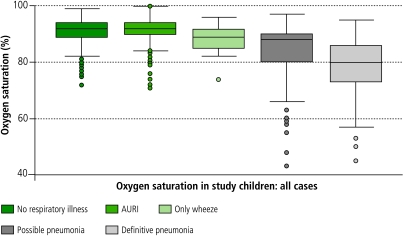

Table 8 and Fig. 1 illustrate SaO2 values for children with non-respiratory diagnoses, AURI, wheezing illness (without pneumonia), and pneumonia (possible, definite). Distributions for the diagnostic categories differ overall (Kruskal-Wallis P = 0.0001). Similar statistically significant differences are seen for readings from the Sims and Nellcor oximeters. Since SaO2 was measured during the consultation, it is possible that diagnosis was influenced by the reading, although a substantial number of non-serious diagnoses (AURI, non-respiratory) had low values recorded, and vice-versa.

Table 8. SaO2 data from physician examination of study children: all casesa.

| Diagnostic group | Number of episodes | Mean (SD) | Median | Minimum | Maximum | 25th–75th centile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No respiratory condition | 654 | 90.8 (4.7) | 92.0 | 72 | 99 | 89–94 |

| Acute upper respiratory infection (without wheeze) | 877 | 91.6 (3.8) | 92.0 | 71 | 100 | 90–94 |

| Wheeze (without pneumonia) | 22 | 88.6 (5.4) | 89.0 | 74 | 96 | 85–92 |

| Possible pneumonia | 205 | 84.8 (9.0) | 88.0 | 43 | 97 | 80–90 |

| Definite pneumonia | 55 | 78.2 (11.6) | 80 | 45 | 95 | 73–86 |

SaO2, oxygen saturation; SD, standard deviation. a Kruskal–Wallis test of differences between diagnostic groups (df = 4): P = 0.0001.

Fig. 1.

Distributions of oxygen saturation readings from children examined by the study physicians, by diagnostic category

AURI, acute upper respiratory infections.

Direct antigen test for RSV

A substantial but widely varying proportion of ALRI cases are reported to be viral,21 although mixed viral and bacterial etiology also occurs.21,22 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the predominant viral agent.21,23 We are aware of only one study reporting on the risk of RSV ALRI associated with IAP finding a protective effect of exposure for severe hospitalized cases (OR = 0.31 for mothers’ cooking at least once daily, 95% CI: 0.14–0.7).24 If reducing IAP does not reduce risk of RSV-related ALRI, failure to distinguish between viral and non-viral cases would mask any impact on bacterial cases. This has added significance because most ALRI deaths result from bacterial infection, probably due to their invasive nature.21,25–27

An enzyme immunoassay test (Becton-Dickinson Directigen RSV) was performed on all children diagnosed with pneumonia (with parental consent), using naso-pharyngeal aspirate following infusion of 1 ml of normal saline. Kits include positive and negative test samples, used at the start and end of each batch. The product manual reports the sensitivity and specificity of this test to be 93–97% and 90–97% respectively.

RSV tests were completed for 236 (89.7%) of the 263 cases of physician-diagnosed pneumonia, but fewer control (87.1%) than intervention (93.6%) cases (0.05 < P < 0.1). Mean SaO2 was 1.2% lower in cases receiving the test (NS).

Referral for chest X-ray

Initially, children diagnosed with pneumonia were referred to San Marcos Hospital for chest X-ray; from April 2004 a private clinic with better quality control was used. Due to apprehension about hospital, and barriers of travel time and cost, initially a substantial proportion of referrals did not attend. During the first six months, the study team worked to build trust and provided transport twice per week. There was less anxiety about attending the private clinic.

All CXRs used the antero-posterior view, and were conducted in 208 (79.1%) pneumonia cases, more intervention (82.3%) than control (76.3%) cases (NS). Median SaO2 was similar in those who did and did not have a CXR. Acceptance varied over the study: lowest during the first year (70%) but rising to 90% during the second. Following training in standardized methods for pneumonia interpretation developed by WHO, two readers (MG, JB) assessed CXRs.28,29 These were reported as: (1) normal; (2) minor changes; (3) major changes, pneumonia or bronchopneumonia, excluding 4 and 5 below; (4) lobar pneumonia or effusion; and (5) overlap between 4 and 5. Good agreement was achieved on five-way classification (Cohen’s kappa = 0.83), and 16 films with disagreement were resolved through consensus reading by two experienced WHO staff. A combination of categories 3, 4 and 5 are taken as radiological evidence of pneumonia. In an attempt to define outcome more strictly (specifically) as primary end-point pneumonia,28 two additional readers reviewed all films (blind). However, agreement was unsatisfactory – all kappa values for pairs with new readers were < 0.4.

Hospital referral

Children requiring hospital admission were referred to San Marcos Hospital, with transport provided. Following discharge or death, hospital clinical information was added to study records. Two additional pneumonia cases admitted by self-referral were obtained from hospital records. CXRs were available, but neither SaO2 nor RSV status.

Deaths

Deaths were investigated by verbal autopsy16 approximately six weeks after death. Interviews were conducted by the field project coordinator (AD) assisted by a bilingual field supervisor, and analysed blind by four WHO readers. During surveillance, 23 deaths occurred (37 per 1000 child years), of which 9 (39%) were due to pneumonia (14.9 per 1000 child years, 95% CI: 7.7–28.6). Verbal autopsies provided 6 additional pneumonia cases, yielding 271 cases in total (0.45 episodes/child/year, 95% CI: 0.40–0.50) and case fatality of 3.3%.

Discussion

The aim of the first stage of case-finding was high sensitivity. Although this cannot be calculated directly, the 47 self-referrals that resulted in a diagnosis of pneumonia provide some indication of false negatives. This must be viewed alongside the large number of cases of respiratory illness without lower respiratory signs referred by fieldworkers, which contributed 49 physician-diagnosed pneumonias. Overall, the weekly visits, referrals (ALRI and AURI) and self-referrals together probably delivered high sensitivity, a conclusion consistent with observed pneumonia rates. The finding that one-third of fieldworker-defined ALRI cases were diagnosed with pneumonia is consistent with the positive predictive value (PPV) expected from the incidence rates of upper and lower respiratory infections in this study and reported sensitivity and specificity of community case-finding.18 It was reassuring to find no evidence of bias by intervention status in the classification of children for referral.

Self-referrals to the physician did not compensate for the differential compliance with fieldworker referral by intervention status. There were more self-referrals for respiratory illness among plancha children, and slightly more of these cases were diagnosed with pneumonia in the intervention group (14.6% versus 13.0%, NS). This, combined with the higher referral compliance for respiratory illness in the plancha group, indicates that intervention cases had a consistently higher likelihood of attending the physician.

Our assessment of physician examinations focused on evidence of bias in the use of clinical signs for diagnosis. The lower proportion of pneumonia cases among intervention children with crepitations was notable. This may be an intervention outcome rather than bias, as diagnosing pneumonia more frequently among plancha children without crepitations seems counterintuitive if blinding of physicians had not been successful.

The investigations (pulse oximetry, RSV test, chest X-ray) were important for increasing specificity and objectivity in outcome assessment. Pulse oximetry was consistent with diagnosis and severity, and with other studies.19 RSV tests were carried out on almost 90% of pneumonias, but control cases had twice as many missed tests as plancha cases. The trend towards higher intervention group compliance was also seen for CXRs.

The nested case-finding allows a range of outcome definitions for analysis of risk estimates, the degree of blindness and objectivity increasing as more specific criteria are introduced (Table 9). Despite incomplete compliance with referral, the rate of physician-diagnosed pneumonia was close to that assumed for power calculation.

Table 9. Outcome definitions and rates for ALRI available from fieldworker assessment, physician examination and investigations.

| ALRI outcome definition | Blindness and objectivity of assessment | Number of cases | Rate/1000/year (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FW-assessed fast breathing, chest wall indrawing, etc. meeting criteria for referral to study physician as possible ALRI | Assessed in homes so not blinded. Assessment by trained FW, with supervision | 668 | 1115 (1033–1203) |

| 2 | FW-assessed “severe WHO pneumonia” defined as (1) above, with chest wall indrawing and/or inability to breastfeed | As above | 72 | 120.2 (95.4–151.4) |

| 3 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia based on history and clinical examination. CXR not available to physician at time of diagnosis | Assessed away from homes, so theoretically blinded. Physicians attended training sessions every 1–2 months to maintain standardized assessment | 263 | 439.0 (389.1–495.4) |

| 4 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia, hospital referral recommended | As (3) above | 64 | 106.8 (83.6–136.5) |

| 5 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with hypoxia measured by pulse oximeter | As (3) above, with additional objectivity of pulse oximeter measurement | 136 | 227.0 (191.9–268.6) |

| 6 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with RSV negative | As (3) above, with additional objectivity of RSV test | 150 | 250.4 (213.4–293.9) |

| 7 | Physician diagnosed pneumonia with RSV positive | As (3) above, with additional objectivity of RSV test | 86 | 143.6 (116.2–177.3) |

| 8 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with hypoxia measured by pulse oximeter, stratified by RSV status | As (3) above, with additional objectivity of pulse oximeter measurement and RSV test | RSV neg, hypox: 69 | 115.2 (91.0–145.8) |

| RSV pos, hypox: 57 | 95.1 (73.4–123.4) | |||

| 9 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with pneumonia on CXR | As (3) above, with additional objectivity of CXRs read blind and independently | 88 | 145.6 (118.1–179.4) |

| 10 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with hypoxia and pneumonia on CXR | As (9) above, with additional objectivity of pulse oximetry readings | 55 | 91.0 (69.8–118.5) |

| 11 | Physician-diagnosed pneumonia with hypoxia and pneumonia on CXR, stratified by RSV status | As (9) above, with additional objectivity of pulse oximetry readings and RSV antigen test result | RSV neg: 32 | 52.9 (37.4–74.8) |

| RSV pos: 22 | 36.4 (23.9–55.3) | |||

| 12 | Pneumonia deaths based on verbal autopsy (VA) approximately 6 weeks after death | VA data collection in homes not blinded. Independent blind interpretation by WHO | 9 | 14.9 (7.7–28.6) |

ALRI, acute lower respiratory infections; CXR, chest x-ray; FW, fieldworker; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus. a Rates for physician-diagnosed pneumonia (and definitions 4–11) are calculated after exclusion of ≥ 3 successive missed weekly home visits from the denominator. This cut-off was selected as children who missed up to 2 successive weeks did contribute to physician-diagnosed cases, and are therefore considered “at risk”. Children missing three or more successive weeks were more likely to have migrated (temporarily) out of the study area, and therefore could not be at risk of a diagnosis of pneumonia by the study physician. Although some pneumonia cases did not receive RSV and/or CXR (see text) the denominator has not been adjusted, therefore these rates are likely to be underestimates.

Conclusions

Although case-finding met the stated aims with reasonable success, there are several issues for analysis, in particular the differential compliance with referral and investigations. Although not large at any one level, this occurs at each stage of the process and will impact most on outcomes using RSV and CXR information. To address this, analyses will include risk estimates adjusted for missing data. The problem of differential compliance, combined with no apparent evidence of bias by intervention group in fieldworker classification in this study, might suggest that referral for physician assessment is not useful. However, it would seem wise to retain blinded clinical and objective (investigation-based) assessment in any trial where intervention concealment at home is not possible. Adding pulse oximetry to home visit ALRI assessment may be worthy of further investigation. ■

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Alfredo Longo and Dr Sofía de León (San Marcos Hospital), Dr Carlos Santizo (Monte Sinai Clinic) and Dr Francisco Arredondo (Esperanza Hospital, Guatemala City) for their clinical assistance; Professor John Balmes and Dr Mike Gotway (University of California, San Francisco) for reading of chest X-rays; Dr Tim Clayton, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, for advice on data analysis. We appreciate the cooperation of our fieldworkers and participants, the Guatemala Ministry of Health, and funding from the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), WHO and the AC Griffin Family Trust.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Rudan I, Tomaskovic L, Boschi-Pinto C, Campbell H. Global estimate of the incidence of clinical pneumonia among children under five years of age. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:895–903. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardlaw T, Salama P, Johansson EW. Pneumonia: the leading killer of children. Lancet. 2006;368:1048–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KR, Mehta S, Feuz M. Indoor air pollution from household use of solid fuels. In: Ezzati M, ed., Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1078–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanata CF, Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Tomaskovic L, Cherian T, Weber M, et al. Methodological and quality issues in epidemiological studies of acute lower respiratory infections in children in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1362–72. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stata [computer program]. 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845 USA: StataCorp; 2006.

- 7.Albalak R, Bruce NG, McCracken JP, Smith KR. Indoor respirable particulate matter concentrations from an open fire, improved cookstove, and LPG/open fire combination in a rural Guatemalan community. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:2650–5. doi: 10.1021/es001940m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boy E, Bruce NG, Smith KR, Hernandez R. Fuel efficiency of an improved wood-burning stove in rural Guatemala: implications for health, environment and development. Energy for Sustainable Development 2000;2:23-31. Available at: http://www.ieiglobal.org/ESDvol4no2/guatemala-stoveabstract.html

- 9.McCracken JP, Smith KR. Emissions and efficiency of improved wood-burning cookstoves in highland Guatemala. Environ Int. 1998;24:739–47. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(98)00062-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naeher L, Smith KR, Leaderer B. Indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and CO in high- and low-density Guatemalan villages. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10:544–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naeher LP, Smith KR, Leaderer B, Neufeld L, Mage D. Carbon monoxide as a tracer for assessing exposures to particulate matter in wood and gas cookstove households in highland Guatemala. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:575–81. doi: 10.1021/es991225g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce N, McCracken J, Albalak R, Schei MA, Smith KR, Lopez V, et al. Impact of improved stoves, house construction and child location on levels of indoor air pollution and exposure in young Guatemalan children. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;(Suppl 1):S26–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engle P, Hurtado E, Ruel M. Smoke exposure of women and young children in highland Guatemala: predictions and recall accuracy. Hum Organ. 1998;54:522–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naeher LP, Leaderer BP, Smith KR. Particulate matter and carbon monoxide in highland Guatemala: indoor and outdoor levels from traditional and improved wood stoves and gas stoves. Indoor Air. 2000;10:200–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2000.010003200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Integrated management of childhood illness [online]. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/child-adolescent-health/publications/IMCI/WHO_CHS_CAH_98.1.htm

- 16.Anker M, Black RE, Coldham C, Kalter HD, Quigley MA, Ross D, et al. A standard verbal autopsy method for investigating causes of death in infants and children Geneva: WHO; 1999 (WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/99.4). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber MW, Milligan P, Giadom B, Pate MA, Kwara A, Sadiq AD. Respiratory illness after severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in infancy. J Pediatr. 1999;135:683–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber MW, Mulholland EK, Jaffar S, Troedsson H, Gove S, Greenwood BM. Evaluation of an algorithm for the integrated management of childhood illness in an area with seasonal malaria in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(Suppl 1):25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozano JM. Epidemiology of hypoxia in children with acute lower respiratory infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:496–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usen S, Weber M. Clinical signs of hypoxaemia in children with acute lower respiratory infection: indicators of oxygen therapy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:505–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber MW, Mulholland EK, Greenwood BM. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in tropical and developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:268–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber MW, Dackour R, Usen S, Schneider G, Adegbola R, Cane P, et al. The clinical spectrum of respiratory syncytial virus disease in the Gambia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:224–30. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson SE, Roca A, Alonso P, Simoes EA, Kartasasmita CB, Olaleye DO, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: denominator-based studies in Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria and South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:914–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber MW, Milligan P, Hilton S, Lahai G, Whittle H, Mulholland EK, et al. Risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection leading to hospital admission in children in the western region of the Gambia. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:157–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shann F, Barker J, Poore P. Clinical signs that predict death in children with severe pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:852–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber MW, Carlin JB, Gatchalian S, Lehmann D, Muhe L, Mulholland EK, et al. Predictors of neonatal sepsis in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:711–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000078163.80807.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salih MAM, Herrmann B, Grandien M, El Hag MM, Yousif BE, Abdelbagi M, et al. Viral pathogens and clinical manifestations associated with acute lower respiratory tract infections in children of the Sudan. Clin Diagn Virol. 1994;2:201–9. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(94)90023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherian T, Mulholland EK, Carlin JB, Ostensen H, Amin R, de Campo M, et al. Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:353–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Standardized interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children. Geneva: WHO; 2001 (WHO/V7B/01.35).

- 30.Low birthweight: country, regional and global estimates. New York: UNICEF; 2004.

- 31.Boy E, Bruce NG, Delgado H. Birthweight and exposure to kitchen wood smoke during pregnancy. 2002;110:109-114. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:109–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]