Abstract

We used a retrospective, matching, birth cohort design to evaluate a comprehensive, coalition-led childhood immunization program of outreach, education, and reminders in a Latino, urban community. After we controlled for Latino ethnicity and Medicaid, we found that children enrolled in the program were 53% more likely to be up-to-date (adjusted odds ratio = 1.53; 95% confidence interval = 1.33, 1.75) and to receive timely immunizations than were children in the control group (t = 3.91). The coalition-led, community-based immunization program was effective in improving on-time childhood immunization coverage.

The most effective strategies for improving community-wide childhood immunization rates combine reminders, tracking, and outreach.1,2 Most evidence about these strategies derives from provider-driven programs, with very little from community-driven programs.3–6 Our immunization program, Start Right, is community driven, but until recently, we have not had community-specific data for demonstrating its effectiveness, relying instead on comparisons to national data.7,8 In this study, we re-examined the program's effectiveness with a comparison cohort in our own community.

METHODS

Prior to the intervention, our Latino, low-income community in New York City had childhood immunization rates of 57%—well below city and national rates.7 To address this problem, Start Right, our 23-partner coalition, adapted national and citywide materials for its own package of bilingual and community-appropriate immunization-promotion materials; trained peer health educators; implemented personalized immunization outreach and promotion within social service and educational programs; provided outreach, education, and reminders to parents; and supported provider immunization delivery1,5,6,9–19 (Table 1). Enrollment, tracking, and accountability were shared among partners.20,21 Participants were recruited through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (27%), facilitated State Children's Health Insurance Program enrollment program (20%), childcare and Head Start centers (20%), parenting assistance programs (19%), and housing and tenant associations (9%). The refusal rate was 2%.

TABLE 1.

Community-Based Immunization-Promotion Program Components

| Strategy | Implementation | Result |

| Membership | A total of 23 community organizations: social services, housing, faith-based, childcare providers, primary care providers, the city health department. | Broad-based constituency. |

| Leadership | Shared leadership, academic, 2 community organizations. | Enhanced coordination and community ownership. |

| Program design | Used community organization needs and experiences and provider perspectives to select evidence-based best practices and to develop bilingual and community-specific outreach and educational materials. | Blend of own experience and national evidence-based insights; enhanced community ownership and relevance of immunization materials. |

| Integration into existing services | Immunization promotion designed as an “add-on” to 5 basic community social service and education programs: parenting assistance, childcare, facilitated enrollment for SCHIP, housing assistance, and WIC. Implementation guide tailored the intervention to each type of program. | Immunization promotion not stand-alone, but incorporated into ongoing programs working with parents of young children. |

| Staff/peer training | Social service and educational staff or peers trained in immunization outreach, education, reminders and tracking with our own bilingual materials and curriculum, including Immunization 101, Card Reading, Tips on Educating Parents, and Methods for Reminding and Tracking Families. | A total of 998 community staff trained in 2000 to 2007, with 150 to 200 active at any given time; enhanced outreach and sustainability through the long-term presence of trained staff in the community. |

| Parental empowerment | Parents learn about immunizations, immunization cards, and the immunization schedule from peers or trusted staff through one-on-one and group sessions. Use of coalition-developed, bilingual, low-literacy materials. | A total of 10 251 parents participated, with 60% receiving one-on-one education, and 40% receiving both group and one-on-one education. Parents like the program and recommend it to friends. |

| Reminders and recall | Parents given calendar dates for when shots are due, reminder phone calls and cards before each immunization due date, and recall phone call, card, or visit if missed. | Average of 2.7 calls, reminders, or visits per child. |

| Tracking | Decentralized immunization tracking at each member organization, consolidating data from parents’ cards and electronic registries. | A total of 184 896 immunization records in the consolidated coalition database, including 24% recorded only on the child's vaccination card. |

Note. SCHIP = State Children's Health Insurance Program; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Study Design

We used a quasi-experimental, retrospective, birth cohort design22,23 with 10 857 children born between April 1999 and September 2003 at the primary community hospital (76% of community births) who resided in the community's zip codes. Following National Immunization Survey methodology, we created 4 annual cohorts of children, aged 19 to 35 months as of April 1 of each year, 2002 to 2005 (n = 2879, 2788, 2653, and 2577, respectively). The annual cohorts were divided into intervention and control groups. The study was conducted retrospectively in 2006 to 2007.

The hospital database was used for demographics; the New York Citywide Immunization Registry (CIR) for immunization records. CIR is a population-based registry with mandated provider reporting. Most children (88%) had a record in CIR (n = 9511; 93.9% of the Start Right group, 87.0% of the control group).

Outcome measures were up-to-date immunizations for the 4:3:1:3:3 series (4 diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis [DTaP]; 3 polio; 1 measles-mumps-rubella; 3 Haemophilus influenza b; and 3 hepatitis B24) and timeliness of the last DTaP dose, known as DTaP4, measured by elapsed days between the date a child became overdue and the immunization date for children with a DTaP4 dose (n = 5059).25 Significance of differences in coverage and timeliness were assessed with the χ2 test and the unpaired 2-sample Student's t test. Logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for the intervention effect on immunization status, controlling for Latino ethnicity and Medicaid enrollment (n = 10 231).26 We used Stata 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Across all birth cohorts, 8.2% (n = 895) enrolled in Start Right. Compared with control groups, children in Start Right were similar in age (mean = 27.4 months) but were more likely to have Medicaid (85.1% vs 78%; χ2 = 27.8; df = 2; P < .001) and be Latino (92% vs 85.1%; χ2 = 39.1; df = 2; P < .001).

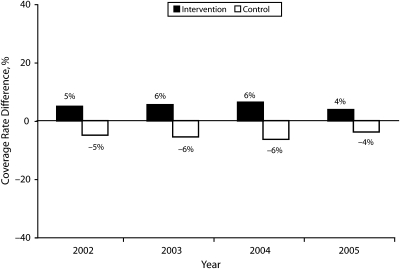

Children in Start Right achieved significantly higher (11.1%) immunization coverage than did control children (χ2 = 44.6; P < .001; Figure 1) and completed the immunization series earlier, by 11 days (t = 3.91). After controlling for ethnicity and Medicaid, children in Start Right were 53% more likely to be up-to-date than were control children (AOR = 1.53; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.33, 1.75). Neither Latino ethnicity (AOR = 1.07; 95% CI = 0.93, 1.24) nor Medicaid (AOR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.95, 1.16) significantly influenced immunization coverage.

FIGURE 1.

Differences in registry-reported immunization coverage rates from the community average: New York City, 2002–2005.

DISCUSSION

Despite similarities at birth and control for ethnicity and Medicaid insurance, less than 3 years later, the children in the Start Right intervention had significantly higher immunization coverage rates than did the rest of their birth cohort. The community birth cohort control further validates our earlier findings regarding the effectiveness of our community-driven, comprehensive immunization-promotion intervention.7,8 The observed increased coverage is not the result of a higher community-wide immunization level, but of the immunization-promotion program year after year. This improvement in coverage is well within the range expected for reminder–recall interventions and other community-based programs.5

The major limitation to this study was incomplete data reporting to the CIR.27,28 In contrast to our previous reports, which included parent-held vaccination card data, we only included registry data in this study. Incomplete provider reporting of immunizations to the CIR, estimated at 85%, may have downwardly biased immunization coverage.29 As indicated in Table 1, including only immunizations reported to the CIR excluded 24% of immunizations recorded on the intervention children's vaccination cards.

We attribute the success of the program to a number of factors, including community ownership of the program, integration of immunization promotion into social service and educational programs, training of a large cadre of peer educators, intense parental education and empowerment, and culturally appropriate reminders arising out of the context of our intervention. We hope that this study helps others seeking ways to embed health care promotion into community programs.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project has been provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U50/CCU222197) and the Bank of America Foundation.

We have many to thank, but none more than the families who participated in the study and our community partners: Alianza Dominicana, Inc; Dominican Women's Development Center; Fort George Community Enrichment Program; Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation; Columbia-Presbyterian Special Supplemental Nutrition Program For Women, Infants, and Children. New York Presbyterian Hospital Ambulatory Care Network; New York City Bureau of Immunization; and Mailman School of Public Health. The study team is particularly indebted to Amy Metroka, Director of the Citywide Immunization Registry, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, who graciously provided the data for the cohort samples per the specifications provided by the Start Right team. We also thank Frank Chimkin, who originally developed the Start Right database and specified the initial immunization registry record requests.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center institutional review board.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors

All authors except R. Andres-Martinez (who joined the team later) participated in the design of the study. M. Irigoyen and M. S. Stockwell obtained the control sample data, and S. Chen and R. Andres-Martinez assembled and analyzed the data. L. Guzman helped develop the Start Right database and, with O. Pena, assured high-quality data inputs from partners. The article was drafted by S. E. Findley, M. Irigoyen, M. Sanchez, and M. S. Stockwell, with assistance in developing the program summary in Table 1 from M. Mejia and R. Ferreira, who also reviewed the final draft of the article.

References

- 1.Szilagyi PG, Bordley C, Vann JC, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates: a review. JAMA 2000;284:1820–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood DL; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Community Health Services; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Increasing immunization coverage. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Community Health Services American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Pediatrics 2003;112:993–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browngoehl K, Kennedy K, Krotki K, Mainzer H. Increasing immunization: a Medicaid managed care model. Pediatrics 1997;99:E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood D, Halfon N, Sherbourne DC, et al. Increasing immunization rates among inner-city, African American children. A randomized trial of case management. JAMA 1998;279:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:97–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer JP, Housemann R, Pipenbrok B. Evaluation of a campaign to improve immunization in a rural head start program. J Community Health 1999;24:13–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Findley S, Irigoyen M, Sanchez M, et al. Community empowerment to reduce childhood immunization disparities in New York City. Ethn Dis 2004;14(3 suppl. 1):S134–S141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findley SE, Irigoyen M, Sanchez M, et al. Community-based strategies to reduce childhood immunization disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006;7(suppl 3):191S–200S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eng E, Parker E, Harlan C. Lay health advisor intervention strategies: a continuum from natural helping to paraprofessional helping. Health Educ Behav 1997;24:413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin S, Dick J, Pond P, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;25(1):CD004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev 2000;57:181–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes K, Friedman SM, Namerow PB, Honig J. Impact of community volunteers on immunization rates of children younger than 2 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:518–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel B, Checkoway B, Schulty A. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational and community control. Health Educ Q 1994;21:149–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoekstra EJ, LeBaron CW, Megaloeconomou Y, et al. Impact of a large-scale immunization initiative in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). JAMA 1998;280:1143–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood D, Halfon N. Reconfiguring child health services in the inner city. JAMA 1998;280:1182–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ryn M, Heaney CA. Developing effective helping relationships in health education practice. Health Educ Behav 1997;24:683–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach . 3rd ed.Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Co; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapore T, Moore A, Acosta R. Developing partnerships with family home day care providers to improve immunization rates in the city of Long Beach. Paper presented at: 34th National Immunization Conference; July 5, 2000; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health through community organization and community building. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM., eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice . 2nd ed.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997:241–269 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Health Promotion Research Guidelines for Participatory Research in Health Promotion . Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi PH, Freeman HE. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach . 3rd ed.Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National, state, and urban area vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:988–993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luman ET, Barker LE, Shaw KM, McCauley MM, Buehler JW, Pickering LK. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in the United States. JAMA 2005;293:1204–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of Biostatistics . 2nd ed.Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Thomson Learning; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolasa MS, Chilkatowsky AP, Clarke KR, Lutz JP. How complete are immunization registries? The Philadelphia story. Ambul Pediatr 2006;6:21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kempe A, Beaty BL, Steiner JF, et al. The regional immunization registry as a public health tool for improving clinical practice and guiding immunization delivery policy. Am J Public Health 2004;94:967–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadouka V, Zucker J, Balter S, Reddy V, Moore K, Metroka A. [Google Scholar]