Doshi1 makes a number of interesting points, including a trenchant observation about the sharing of surveillance data collected under public auspices. Doshi's conclusion that “the next influenza pandemic may be far from a catastrophic event,”1(p944) may turn out to be true. However, the author's optimism is not supported by his analysis, which omits pneumonia.

Doshi contends that the mortality consequences of influenza pandemics have been overstated. Epidemiologists, demographers, and vital statisticians analyze mortality from influenza and pneumonia combined as a single cause. This is because influenza kills through pneumonia and is coded as such on death certificates. Concern about “laboratory confirmation”1(p939) of influenza may be germane in the clinic, but vis-à-vis historical time series, it is nothing more than splitting hairs.

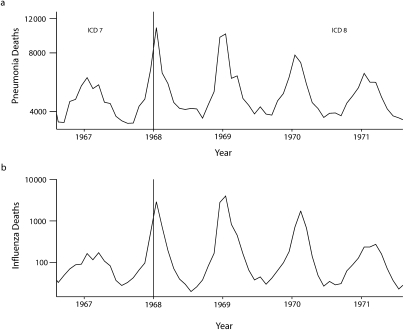

Influenza pandemics occur when new strains of influenza A virus emerge. Consider the most recent pandemic in 1968–1969, when H3N2 influenza emerged. Figure 1 shows time series data on mortality in the United States, from the multiple cause of death data files,2 for 60 months encompassing the 1966–1967 to 1970–1971 flu seasons. It is easy to see that the 1968–1969 pandemic brought not just increases in influenza mortality, but also pneumonia mortality. The resemblance between the 2 panels is uncanny, but pneumonia kills more people. Looking at influenza deaths alone misses most of the story.

FIGURE 1.

Monthly mortality time series for pneumonia (a) and influenza (b): United States, 1966–1967 through 1970–1971 influenza seasons.

Note. The vertical line marks the division between International Classification of Diseases, 7th and 8th Revisions,3,4 death classifications.aExcludes deaths coded as influenza.

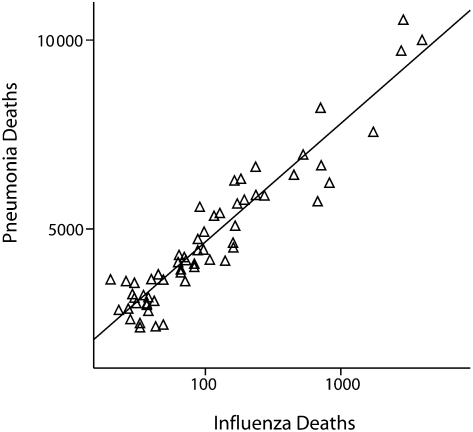

How much are influenza and noninfluenza pneumonia in lockstep? Figure 2 is a scatter plot of influenza deaths (x-axis) versus noninfluenza (viz., no explicit mention of influenza) pneumonia deaths (y-axis), on a log–log scale, with linear fit. The data are the same as those from the 60 months plotted in Figure 1. The linear fit is very strong (R2 = 0.89). This could be dismissed as mechanical correlation, because both causes are cyclical and in phase. However, we see from Figure 1 that, even comparing only winter peaks, whenever influenza rises, so does pneumonia. This may be attributed to the 1968–1969 pandemic—but that's the point.

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plot of number of deaths from influenza and pneumonia: United States, 1966–1967 through 1970–1971 influenza seasons.

Note. 1 data point = 1 month. Both axes are logarithmic. The least-squares fit line is also shown; R2 = 0.89.

Some pneumonia is caused by respiratory syncytial virus, and others like it, but why does pneumonia mortality spike during influenza pandemics and covary so strikingly with influenza mortality? Is it plausible that respiratory syncytial virus becomes more deadly when new strains of influenza emerge? A more likely explanation is that many influenza deaths are being coded as pneumonia deaths. Thus, the usual practice of looking at pneumonia and influenza mortalities combined is wiser than looking at influenza mortality, sensu stricto.

The 1977–1978 flu season serves as a closing vignette for Doshi. The 1977 reemergence of H1N1 was not a pandemic because it was not an antigenic shift. It was believed to have escaped from a laboratory and was identical to strains from 1950, and the world population 20 years and older was largely immune.5 Doshi uses the occasional aberrant classification of 1977 to argue that there is no “a priori connection”1(p944) between pandemics and mortality. With the use of properly classified pandemics, the connection is an empirical one, not a priori. The connection is strong, and Doshi's discussion of 1977 is the sort of sophistry that takes hold when standard practice is summarily set aside without good reason.

That pandemics are high-mortality events is fact, not, as Doshi states, a “false assumption.”1(p944) To avoid such pitfalls, analysis of influenza time series should include pneumonia.

References

- 1.Doshi P. Trends in recorded influenza mortality: United States, 1900–2004. Am J Public Health 2008;98:939–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics Mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/dvs/mcd/msb.htm. Accessed July 18, 2008

- 3.International Classification of Diseases, Seventh Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1957 [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev 1992;56:152–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]