Abstract

Objectives. We investigated the effect of spousal bereavement on mortality to document cause-specific bereavement effects by the causes of death of both the predecedent spouse and the bereaved partner.

Methods. We obtained data from a nationally representative cohort of 373 189 elderly married couples in the United States who were followed from 1993 to 2002. We used competing risk and Cox models in our analyses.

Results. For both men and women, the death of a predecedent spouse from almost all causes, including various cancers, infections, and cardiovascular diseases, increased the all-cause mortality of the bereaved partner to varying degrees. Moreover, the death of a predecedent spouse from any cause increased the survivor's cause-specific mortality for almost all causes, including cancers, infections, and cardiovascular diseases, to varying degrees.

Conclusions. The effect of widowhood on mortality varies substantially by the causes of death of both spouses, suggesting that the widowhood effect is not restricted to one aspect of human biology. Future research should examine the specific mechanisms of the widowhood effect and identify opportunities for health interventions.

The increased likelihood for a recently widowed person to die—often called the “widowhood effect”—is one of the best documented examples of the effect of social relations on health.1 The widowhood effect has been found among men and women of all ages throughout the world.2–5 Recent longitudinal studies put the excess mortality of widowhood (compared with marriage) among the elderly between 30% and 90% in the first 3 months and around 15% in the months thereafter.1,6–8 These estimates are comparable across various statistical methodologies, including multivariate models that statistically control for a wide range of confounding factors,1,6,8,9 prompting increasing confidence in a causal basis of the widowhood effect.6,8,10,11

Most previous studies on the widowhood effect, however, have focused on overall (i.e., all-cause) mortality. By comparison, much less is known about the link between widowhood and specific causes of death. Cause specificity in the widowhood effect can be traced in 2 ways: by the cause of death of the predecedent spouse and by the cause of death of the bereaved partner. Research on either dimension of cause specificity is scarce, particularly research that accounts for the cause of death of the predecedent spouse. This is regrettable as cause specificity of the widowhood effect may help illuminate the specific mechanisms by which the death of a spouse increases the mortality of the survivor and may thus help identify opportunities for health interventions.

Previous work in this area, often using a narrow list of disease categories, has yielded mixed results. For example, whereas several large studies have found that spousal bereavement is associated with increased death from cancer,12–14 several other studies4,7,15–19—including the only 2 longitudinal studies that consider multiple causes of death in the United States4,7—found evidence that was not statistically significant or was inconsistent for increased cancer mortality after widowhood, after adjusting for covariates.

To address this deficit in knowledge, our study investigated variation in the widowhood effect by the causes of death of both spouses using a detailed list of causes of death from a large, longitudinal, and nationally representative sample of elderly married couples. Specifically, we analyzed 2 questions. First, does the death of a predecedent spouse (from any cause) affect the bereaved partner's risk of dying from certain causes more than it affects his or her risk of dying from certain other causes? Second, does the bereaved partner's all-cause mortality depend on the specific cause of death of the predecedent spouse? We analyzed these questions separately for men and women and offer interpretations linking our results to the possible mechanisms underlying the relationship between widowhood and mortality.

METHODS

Data

We developed a very large longitudinal sample of elderly married couples in the United States from Medicare databases (available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services upon application).20,21 Married couples in the 1993 Medicare Denominator file, which contains 96% of all elderly Americans,22 were identified by following previously published identification procedures.23 To satisfy computer processor constraints, we drew an 8% simple random sample from the pool of all identified married couples, which we further restricted to couples in which both spouses were White or both were Black; aged 67 to 98 years at baseline (January 1, 1993); not enrolled in a health maintenance organization; lived in the 50 states or Washington, DC; and shared the same zip code (to exclude married but separated couples). The final sample contained 373 189 married couples or 746 378 men and women. Table 1 compares this Medicare-based sample of elderly married couples to elderly married couples in the 5% Public Use Micro Sample of the 1990 US Census (using corresponding sample restrictions).24 This comparison demonstrates close agreement between our sample and the census with respect to spouses’ age, poverty status, race, and region of residence (all variables common to both data sets). Follow-up extends over 9 years (January 1, 1993, to January 1, 2002).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Sociodemographic Variables among US Black and White Married Couples, Aged 67 to 98 Years, by Sample Source: 1993 Medicare-Based Sample and 5% Public Use Micro Sample of the 1990 US Census

| Variables | Medicare (n = 373 189) | Census (n = 272 306) |

| Mean age, y | ||

| Husband | 76.6 | 75.4 |

| Wife | 74.2 | 73.1 |

| Wives older than husband, % | 21.0 | 19.5 |

| Black race, % | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| Poor,a % | 4.7 | 5.6 |

| Census Region of Residence,b % | ||

| Northeast | 18.8 | 21.3 |

| Midwest | 29.5 | 25.8 |

| South | 36.6 | 34.0 |

| West | 15.2 | 18.9 |

Medicare-based sample uses dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid as proxy for the federal poverty level. Census uses 1990 federal poverty level.

We combined the 9 census divisions used in the statistical analysis into 4 census regions to conserve space.

Measures

Death and widowhood.

The Medicare Vital Status file provided exact death dates for all individuals in the sample who died during the study period. From these death dates, we derived the outcome (time to death since January 1, 1993) and the key independent variable (widowhood). Survival times for surviving sample members were censored at the end of follow-up on January 1, 2002. During the 9 years of follow-up, 52.3% of the husbands and 32.7% of the wives in this sample died.

Cause of death.

Medicare records do not contain death certificates, but they do contain prospectively collected diagnostic histories for all individuals up to their date of death. We adapted an algorithm described by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission to derive causes of death from the complete set of inpatient and outpatient diagnostic records during the last 2 years of decedents’ lives.25 We designed this algorithm to identify the underlying health condition most likely to have killed the decedent. For example, we assigned a cause of death of lung cancer to an individual with no previous conditions who was hospitalized with a diagnosis of lung cancer 3 months before death even if the individual later sought outpatient treatment for an eye infection. By doing this, 48.2% of assigned causes of death coincided with the primary diagnosis of decedents’ hospital record on the day of their death because most patients in the United States are hospitalized at the time of their death. We grouped causes of death into 16 categories according to designations in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.26 Decedents who did not have hospital or outpatient records in the 2 years before death were assigned the category “cause unknown” (8.1%; as a 17th “cause”). Table 2 shows the distribution of causes of death for decedent husbands and wives; this distribution bears a satisfactory overall resemblance to the distribution of causes of death in elderly decedents as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.27

TABLE 2.

Causes of Death Among US Black and White Married Couples (n = 373 189) Aged 67 to 98 years, by Gender: Medicare-Based Sample, 1993–2002

| Cause of death | Men, No. (%) | Women, No. (%) |

| Total, No. | 195 258 (100) | 122 042 (100) |

| Infections and sepsis | 3 519 (1.8) | 2 691 (2.2) |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 5 506 (2.82) | 3 036 (2.49) |

| Colon cancer | 3 747 (1.92) | 2 385 (1.95) |

| Lung cancer | 7 953 (4.07) | 3 570 (2.93) |

| Quick cancersa | 9 854 (5.05) | 5 968 (4.89) |

| Other cancers | 17 691 (9.06) | 11 771 (9.65) |

| Diabetes | 7 766 (3.98) | 5 705 (4.67) |

| Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases | 4 023 (2.06) | 2 286 (1.87) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 16 047 (8.22) | 8 982 (7.36) |

| Congestive heart failure | 19 161 (9.81) | 10 898 (8.93) |

| Other cardiac or vascular disease | 16 736 (8.57) | 10 113 (8.29) |

| CVA or stroke | 15 409 (7.89) | 11 400 (9.34) |

| COPD | 12 741 (6.53) | 6 244 (5.12) |

| Nephritis or kidney disease | 3 959 (2.03) | 1 957 (1.6) |

| Accidents and serious fractures | 3 430 (1.76) | 2 746 (2.25) |

| All other known causes | 32 840 (16.82) | 21 563 (17.67) |

| Cause unknown | 14 876 (7.62) | 10 727 (8.79) |

Note. CVA = cerebral vascular accident; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Rarer cancers that typically and predictably lead to death quickly; includes cancers of the head, neck, upper gastrointestinal tract, liver, central nervous system, and pancreas and melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia.

Covariates.

The analysis adjusted for numerous medical, social, and contextual covariates that may confound the relation between widowhood and mortality. All covariates were measured at or before baseline (January 1, 1993). Importantly, we adjusted for the characteristics of both members of the couple. On the individual level, we adjusted for the age and race (Black or White) of both spouses.8,28,29 We constructed a couple-level poverty indicator from spouses’ dual Medicare–Medicaid eligibility.30 We extracted detailed health histories from the 1991 and 1992 Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files to adjust for baseline morbidity. We summarized the chronic disease burden at baseline by computing so-called Charlson comorbidity scores from hospitalization records separately for each spouse in 1991 and 1992.31 We trichotomized this measure of disease burden into low, moderate, and severe (Charlson scores of 0, 1, and 2 or higher, respectively).32 We further adjusted for the number of days each spouse had spent in the hospital in 1991 and in 1992. We also adjusted for couples’ census division of residence as well as detailed measures of residential context: At the county level, we adjusted for population density, violent crime rate, and the availability of medical care as reported in the Area Resource File.33 At the zip code level, we adjusted for urbanization, demographic composition (age, race, foreign birth, language spoken), male unemployment rates, median home value, log median income, and median education, all drawn from the 1990 Census Summary Tape File 3B.34

Statistical Methods

We present 2 analyses, each estimated separately for men and women. We refer to the focal individual whose mortality risk during bereavement was being assessed—whether a husband or a wife—as the “partner” of the predecedent spouse. For readability, we suppress individual-level subscripts i. First, we estimated a continuous-time Cox competing risk model to analyze the impact of the predecedent spouse's death (from any cause) on the partner's hazard of dying from each of 17 causes of death.35

| (1) |

Equation 1 partitions partners’ hazard of dying from specific cause c at time t, hc (t ), into the product of a cause-specific baseline hazard that varies freely with time, h0,c (t ), and a function of the vector of explanatory variables, such that changes in the explanatory variables induce proportional shifts in the baseline hazard. The model contains a time-varying widowhood indicator, W(t ), which switches from 0 to 1 on the day of the spouse's death, and a time-invariant vector of baseline covariates, X. We allowed the impact of each variable on partners’ cause-specific hazard of death to vary freely across partners’ potential causes of death. Thus, the key parameter of interest, b2,c, gives the impact of widowhood on a partner's hazard of dying from cause c, after adjusting for covariates, X. Under the assumption that the cause-specific hazards of death are independent given observed covariates, the model likelihood partitions into c components, which each depend only on parameters relating to one specific cause. We can then estimate equation 1 as a series of c independent cause-specific Cox models, where survival times in each cause-specific model are censored if partners die of a different cause first.35

In the second analysis, we used standard continuous-time Cox models to estimate the impact of the spouse's death from a specific cause on the partner's overall hazard of death.

| (2) |

Equation 2 partitions the partner's overall hazard of death at time t, h(t ), into a time-varying baseline hazard, h0(t ), and a function of explanatory variables. The vector of covariates, X, is the same as in equation 1. Here, however, we entered not 1 overall indicator of widowhood but a vector of 17 separate, cause-specific widowhood indicators, Wc (t ), 1 for each of the spouse's possible causes of death (with “spouse alive” as the reference category). The vector of key parameters of interest, b2,c, gives the impact of the spouse's death from cause c on the partner's overall hazard of death, after adjusting for covariates, X.

More complicated analyses (not shown) that simultaneously accounted for the full 17 × 17 matrix of potential causes of death in the partners and their spouses did not further illuminate the results of this study. All results are fully adjusted for the covariates listed here. We performed the analyses using Stata version 9.2.36

RESULTS

Mortality after widowhood is significantly elevated for husbands and wives. The death of a wife is associated with an 18% increase in all-cause mortality for men (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.16, 1.19), and the death of a husband is associated with a 16% increase in all-cause mortality for women (HR = 1.16; 95% CI = 1.14, 1.17), after adjusting for covariates.

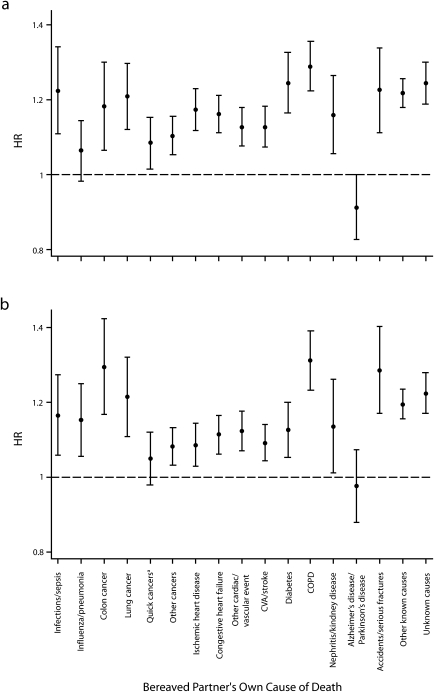

Widowhood Effects by the Causes of Death of Surviving Partners

Figure 1 shows HRs and 95% CIs for the estimated effects of spouse's death (from any cause) on partner's cause-specific hazards of death, after adjusting for covariates. The results of causes for which the confidence interval overlaps with the horizontal line of no effect (HR = 1) are not statistically significant at the conventional 5% level. The impact of widowhood differs across partners’ 17 possible causes of death, and this difference is statistically significant (P < .01) for both husbands and wives. That is, widowhood does not raise the risk of all causes of death uniformly. We further note that the cause-specific widowhood effects for husbands correlate strongly with the corresponding cause-specific widowhood effects for wives (ρ = 0.77), although men on average tend to suffer somewhat stronger repercussions.

FIGURE 1.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of widowhood (from any cause) on cause-specific mortality among bereaved men (a) and women (b): Medicare-based cohort of Black and White married couples, aged 67 to 98 years at baseline (n = 373 189), United States, 1993–2002.

Note. CVA = cerebral vascular accident; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Estimates from Cox models were adjusted for all baseline covariates. There are separate models for husbands and wives. aCancers of the head, neck, upper gastrointestinal tract, liver, central nervous system, or pancreas and melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia.

A wife's death exerts statistically significant effects (P < .05) on men's cause-specific hazards of death for 15 out of 17 causes of death. A wife's death increases men's cause-specific hazards of death by more than 20% for 6 causes of death (in decreasing order: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], diabetes, accidents or serious fractures, infections or sepsis, all other known causes, and lung cancer) and for unknown causes of death. The effect exceeds 10% for 7 more causes of death (colon cancer, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, nephritis or kidney disease, cerebral vascular accident or stroke, other heart and vascular diseases, and other cancers). The effects of the wife's death on the husband's hazards of death from influenza or pneumonia and Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease are not statistically significant.

A husband's death exerts statistically significant effects on women's cause-specific hazards of death for 15 out of 17 causes of death. The estimated effects exceeded 20% for 4 causes of death (COPD, colon cancer, accidents or serious fractures, and lung cancer) and for unknown causes. The effects exceeded 10% for another 7 causes (other known causes, infections or sepsis, influenza or pneumonia, nephritis or kidney disease, diabetes, other heart or vascular disease, and congestive heart failure). The impact remains statistically significant yet falls below 10% for 3 causes of death (cerebral vascular accident and stroke, ischemic heart disease, and other cancers). We did not find a statistically significant impact of the husband's death on the wife's hazard of death from rapidly fatal cancers or Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease.

For husbands and wives alike, the estimated effect of a spouse's death on dying from Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease is negative: the death of a spouse may reduce the risk of dying from these diseases, but neither effect reaches statistical significance at the conventional 5% level.

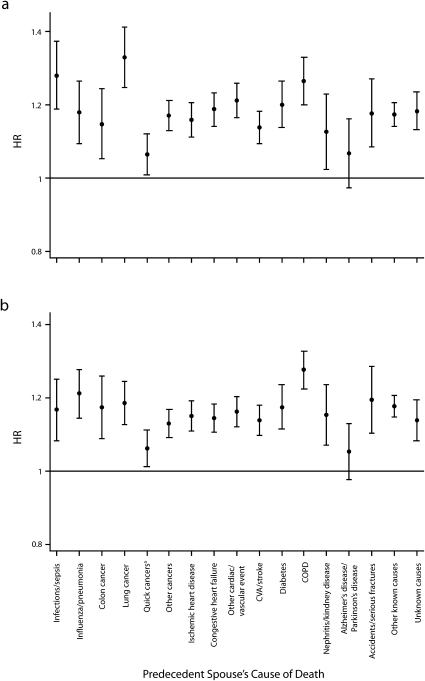

Widowhood Effects by the Causes of Death of Predecedent Spouses

Figure 2 shows the impact of the predecedent spouse's cause of death on the survivor's all-cause hazard of death, after adjusting for covariates. We note that the impact of widowhood on a partner's all-cause mortality varies considerably according to the cause of death of the predecedent spouse (P < .01) for both husbands and wives. As in the preceding analysis, the profile of effects found for husbands strongly correlates with the profile for wives (ρ = .72).

FIGURE 2.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of widowhood on all-cause mortality, by the cause of death of the predecedent spouse, among bereaved men (a) and women (b): Medicare-based cohort of Black and White married couples, aged 67 to 98 years at baseline (n = 373 189), United States, 1993–2002.

Note. CVA = cerebral vascular accident; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Estimates from competing risk models were adjusted for all baseline covariates. There are separate models for husbands and wives. aCancers of the head, neck, upper gastrointestinal tract, liver, central nervous system, or pancreas and melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia.

The death of a husband or wife is associated with a statistically significant (P < .05) increase in the all-cause mortality of the surviving partner for almost all causes of death of the predecedent spouse.

Men's hazard of death increases by more than 20% if their wives died of lung cancer, infections or sepsis, COPD, other heart or vascular diseases, or diabetes. Men's hazard of death increases by less than 20% if their wives died of any other causes. Only men whose wives died of Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease do not experience a statistically significant increase in mortality.

Women's hazard of death increases by more than 20% after widowhood only for 2 of their predecedent husbands’ causes of death: COPD and influenza or pneumonia. Women's hazard of death increases by less than 20% in response to their husbands’ deaths from all other causes. Only women whose husband died of Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease did not experience a statistically significant increase in their own mortality.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the largest nationally representative and longitudinal study of cause specificity in the widowhood effect in the United States. It is also the first such study to investigate variation in the widowhood effect by the causes of death of both spouses, that is, of the predecedent spouse and the bereaved partner.

We found that the widowhood effect is not monolithic. The extent to which widowhood increases the mortality of a surviving partner depends on the cause of death of their predecedent spouse. Moreover, surviving partners are at greater risk of some causes of death than of others after the death of their spouse. This variation according to the causes of death of both spouses provides some analytic advantage to better understand the nature and mechanism of the widowhood effect. Because more than 13 million Americans are widowed37 and because the excess risk of mortality imposed by widowhood is nontrivial, this phenomenon is of substantial public health significance.

Our work goes beyond previous work in this area in a number of ways. Previous research often considered only a small number of causes of death, such as the broad categories of cancer or violent deaths15,38–41; used samples with relatively small numbers of cases for each individual cause of death; used samples that were not nationally representative4,36,37,40; used a cross-sectional methodology12,14; or did not adjust for confounding factors beyond age, gender, and race.12,14,17,40,41 By contrast, in our study, we considered 17 causes of death separately for both spouses in a longitudinal and nationally representative sample of 373 189 married couples experiencing a total of 317 300 deaths while adjusting for a wide range of covariates, including baseline health, that were measured for both members of the couple. These detailed, physician-ascertained statistical controls for confounding by health status significantly exceed the health information available to previous cause-specific studies of the widowhood effect.

Our results suggest several observations regarding the effect of widowhood on spouses’ cause-specific mortality. First, unlike several,4,7,15–19 but not all,12–14 previous studies, we found a statistically significant effect of widowhood on cancer mortality for the elderly. The impact is particularly large for deaths from colon and lung cancer. It is much smaller (and statistically insignificant for wives) for certain rarer cancers that typically and predictably lead to death quickly (cancer of the head and neck, upper gastrointestinal tract, liver, central nervous system, or pancreas and melanoma, lymphoma, or leukemia), and it is small but still significant for all other cancers.

Second, in agreement with most,12,13,16,17,42 though not all,4,7,18 previous studies, we found a clear, positive, and statistically significant association between widowhood and partners’ mortality from vascular diseases for men and women. The effect is moderately strong and is approximately the same (no statistically significant difference) for all 4 categories of cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebral vascular accident or stroke, and other heart or vascular disease).

Third, the multifarious effects of widowhood on the different types of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes of death suggest that widowhood triggers a broad set of biopsychosocial mechanisms that affect mortality and that the impact is not limited to 1 aspect of human biology. Widowhood appears to have particularly strong effects on death from causes that are either acute health events (e.g., infections or sepsis, accidents) or chronic diseases that require careful patient management to treat or prevent (e.g., diabetes, COPD, colon cancer). This suggests that the loss of social support and social integration in widowhood may play a role in the origin of the widowhood effect.43

Many of the observations also apply to the differences in surviving partners’ all-cause mortality in response to the specific causes of death of their predecedent spouses. The lack of increased all-cause mortality following spouses’ death from Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease confirms a similar finding from a British study that attributed the lack of a widowhood effect to anticipatory grief, that is, the ability of caregivers to prepare adequately for the death of their spouse.39 The theory of anticipatory grief is also consistent with our finding of similarly small (albeit statistically significant) widowhood effects in the wake of a spouse's death from cancers that typically lead to death quickly. This suggests that it may be the predictability of the death rather than the duration of the spouse's terminal illness that shields the survivor from some of the adverse consequences of bereavement.

The lack of a widowhood effect following a spouse's death from Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease, however, is also consistent with an alternative explanation. It is possible that spouses suffering from these diseases simply cease to contribute to their partner's health long before they die. Alternately, it may be that the health consequences of caring for a person with Alzheimer's disease has already been absorbed by the end of the sick spouse's life, such that there is no measurable discontinuity in the survivor's mortality at the actual time of spousal death.44

Finally, we note that the differences in husbands’ all-cause mortality across their predecedent wives’ causes of death appear to be somewhat larger than the differences observed for wives. This may indicate that for women it matters most that their husband died, whereas for men it additionally matters what caused their wife's death.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, despite adjusting for a more extensive set of potentially confounding variables than most previous research, including baseline health, there may be some residual unobserved factors that may explain certain features of the reported findings. Specifically, we note that the large impact of widowhood on mortality from COPD and lung cancer in husbands and wives may in part be attributable to shared behaviors, such as smoking,1,2 and the large impact on death by accidents and fractures may be attributable to incidents involving both spouses.6,13,17 On the other hand, our analysis treats same-day deaths as nonwidowed deaths, which should reduce the sensitivity of our results to confounding from common accidents. Furthermore, if unobserved factors were driving all cause-specific results, we would expect that contagious diseases more generally would be associated with large effects, which is the case for infections and sepsis but not for influenza and pneumonia. Second, we derived causes of death from decedents’ diagnostic history rather than from official death certificates. This led to an unavoidable underascertainment of causes that lead to death suddenly or without previous detection.

This longitudinal study of 373 189 elderly American couples shows that the effect of widowhood on mortality varies substantially by the causes of death of both spouses. We found these results for husbands and wives, even after adjusting for a wide range of potentially confounding factors, including the health of both spouses. Widowhood increases survivors’ risk of dying from almost all causes, including cancer, but it increases the risk for some causes more than for others. The converse also holds: widowhood increases survivors’ all-cause mortality in response to almost all causes of death of the predecedent spouse, but the actual cause of death of the predecedent spouse makes a difference. The death of a spouse, for whatever reason, is a significant threat to health and poses a substantial risk of death by whatever cause.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to N. A. Christakis (R-01 AG17548-01) and a Harvard University Eliot Fellowship to F. Elwert.

The authors thank Laurie Meneades for the expert data programming required to develop the analytic data set, Andrew Clarkwest for computing US Census statistics, T. Jack Iwashyna for advice on developing the cause of death classifications, and Wyatt Hong, Pekka Martikainen, Peter A. DeWan, Christopher Winship, and Lawrence Wu for helpful discussions.

Human Subject Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Harvard Medical School.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors

F. Elwert conceptualized the study, contributed to data development, executed the analysis, interpreted the results, and led in the writing of the article. N. A. Christakis conceptualized the study, led data development, interpreted the results, and contributed to the writing of the article.

References

- 1.Schaefer C, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Wi S. Mortality following conjugal bereavement and the effects of a shared environment. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:1142–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraus AS, Lilienfeld AM. Some epidemiologic aspects of the high mortality rate in the young widowed group. J Chronic Dis 1959;10:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkes CM, Benjamin B, Fitzgerald RG. Broken heart: a statistical study of increased mortality among widowers. Br Med J 1969;1:740–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helsing KJ, Comstock GW, Szklo M. Causes of death in a widowed population. Am J Epidemiol 1982;116:524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu YR, Goldman N. Mortality differentials by marital status: an international comparison. Demography 1990;27:233–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Mortality after the death of spouse in relation to duration of bereavement in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996;50:264–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson NJ, Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Loveless CA. Marital status and mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study. Ann Epidemiol 2000;10:224–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elwert F, Christakis NA. Widowhood and race. Am Sociol Rev 2006;71:16–41 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanian SV, Elwert F, Christakis NA. Widowhood and mortality among the elderly: the modifying role of neighborhood concentration of widowed individuals. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:873–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillard LA, Panis CW. Marital status and mortality: the role of health. Demography 1996;33:313–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillard LA, Waite LJ. ’Til death do us part: marital disruption and mortality. AJS 1995;100:1131–1156 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgoa M, Regidor E, Rodriguez C, Gutierrez-Fisac JL. Mortality by cause of death and marital status in Spain. Eur J Public Health 1998;8:37–42 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Mortality after the death of a spouse: rates and causes of death in a large Finnish cohort. Am J Public Health 1996;86:1087–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gove WR. Sex, marital status mortality. AJS 1973;79:45–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones DR, Goldblatt PO, Leon DA. Bereavement and cancer: some data on deaths of spouses from the longitudinal study of Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:461–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones DR, Goldblatt PO. Cause of death in widow(er)s and spouses. J Biosoc Sci 1987;19:107–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Rita H. Mortality after bereavement: a prospective study of 95,647 widowed persons. Am J Public Health 1987;77:283–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebrahim S, Wannamethee G, McCallum A, Walker M, Shaper AG. Marital status, change in marital status, and mortality in middle-aged British men. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:834–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gore JL, Kwan L, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Marriage and mortality in bladder carcinoma. Cancer 2005;104:1188–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauderdale DS, Furner SE, Miles TP, Goldberg J. Epidemiologic uses of Medicare data. Epidemiol Rev 1993;15:319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell JB, Bubolz T, Paul JE, et al. Using Medicare claims for outcomes research. Med Care 1994;32(suppl 7):JS38–JS51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatten J. Medicare's common denominator: the covered population. Health Care Financ Rev 1980;27:53–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwashyna TJ, Zhang JX, Lauderdale DS, Christakis NA. A methodology for identifying married couples in Medicare data: mortality, morbidity, and health care use among the married elderly. Demography 1998;35:413–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. Census of Population and Housing, 1990: Public Use Microdata Sample: 5-Percent (A) Sample—United States Washington DC: US Dept of Commerce, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan C, Lynn J, Gabel J, Lunney J, O'Mara A, Wilkinson A. Medicare Beneficiaries’ Costs and Use of Care in the Last Year of Life . Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arias E, Smith BL. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2001 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arday SL, Arday DR, Monroe S, Zhang J. HCFA's racial and ethnic data: current accuracy and recent improvements. Health Care Financ Rev 2000;21:107–116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauderdale DS, Goldberg J. The expanded racial and ethnic codes in the Medicare data files: their completeness of coverage and accuracy. Am J Public Health 1996;86:712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark WD, Hulbert MM. Research issues: dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, challenges and opportunities. Health Care Financ Rev 1998;20:1–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang JX, Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA. The performance of different lookback periods and sources of information for Charlson comorbidity adjustment in Medicare claims. Med Care 1999;37:1128–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions. Area Resource File (ARF) System Fairfax, VA: Quality Resource Systems Inc; February 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Census Bureau. Census of Population and Housing, 1990: Summary Tape File 3B—United States Washington DC: US Dept of Commerce, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stata Statistical Software Release 9.2 College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoenborn CA. Marital Status and Health: United States, 1999–2002 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan DH. Death in dementia: a study of causes of death in dementia patients and their spouses. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1992;7:465–472 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan DH. Is there a desolation effect after dementia? A comparative study of mortality rates in spouse of dementia patients following admission and bereavement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1992;7:331–339 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith JC, Mercy JA, Conn JM. Marital status and the risk of suicide. Am J Public Health 1988;78:78–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luoma JB, Pearson JL. Suicide and marital status in the United States, 1991–1996: is widowhood a risk factor? Am J Public Health 2002;92:1518–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ben-Shlomo Y, Smith GD, Shipley M, Marmot MG. Magnitude and causes of mortality differences between married and unmarried men. J Epidemiol Community Health 1993;47:200–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA. Marriage, widowhood health-care use. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:2137–2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christakis NA, Allison PD. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med 2006;354:719–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]