Abstract

The law is a frequently overlooked tool for addressing the complex practical and ethical issues that arise from the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The law intersects with reproductive and sexual health issues and HIV/AIDS in many ways. Well-written and rigorously applied laws could benefit persons living with (or at risk of contracting) HIV/AIDS, particularly concerning their reproductive and sexual health.

Access to reproductive health services should be a legal right, and discrimination based on HIV status, which undermines access, should be prohibited. Laws against sexual violence and exploitation, which perpetuate the spread of HIV and its negative effects, should be enforced. Finally, a human rights framework should inform the drafting of laws to more effectively protect health.

AFTER MORE THAN 25 YEARS of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the need for new strategies to combat HIV remains urgent. Approximately 33.2 million people throughout the world are living with HIV,1 and an estimated 25 million have died from the virus.2 The demographics of HIV incidence and prevalence have changed over time. Women suffer an increasing number of these infections and deaths, accounting for nearly half of HIV infections worldwide.3 In sub-Saharan Africa, where infection rates are highest, nearly 61% of the adult infections strike women.4 Globally, the pandemic has infiltrated all areas of life and has particularly affected reproductive and sexual health.

Some of the most contentious and challenging public health issues arising from the HIV/AIDS pandemic involve reproductive and sexual health.5 The most common route of HIV transmission in most parts of the world is through sexual intercourse, which fuels much of the unique and powerful stigma associated with the infection. Sexual activity is integral to human existence, and the social perceptions of the association between HIV/AIDS and sexual activity complicate HIV prevention and treatment strategies. Potentially effective prevention strategies, including innovative reproductive health strategies, become embroiled in debate and then are ignored or dismissed because of political sensitivities. As a result, communities are denied the most effective strategies to prevent HIV, which most greatly affects the health and safety of women and children.

Societal pressures and antiquated laws place women at a significant disadvantage to men in accessing health care services.6 Reproductive health services such as contraception, family planning counseling, and prenatal care are out of reach for many women.7 Women are biologically more susceptible than are men to HIV infection through heterosexual intercourse, a reality that is often exacerbated by systemic gender inequality and poverty.8 They are also less likely than are men to have the resources to access HIV prevention and treatment services.9 Not surprisingly, women and girls have higher infection rates than do men and boys in many of the most affected countries.10

The law plays a critical role in promoting reproductive and sexual health. Legislation and litigation are frequently overlooked tools for addressing the complex practical and ethical issues that arise from the pandemic. Our global comparative analysis of the law, sponsored and published by the World Bank,11 found that the law intersects with reproductive and sexual health issues and HIV/AIDS in numerous ways. Moreover, well-designed legislation and regulation could help create systemic changes to support prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, promote reproductive and sexual health, and help correct societal conditions that contribute to the propagation of the pandemic. We analyzed the laws and policies of many countries that affect the HIV/AIDS pandemic and sexual and reproductive health.

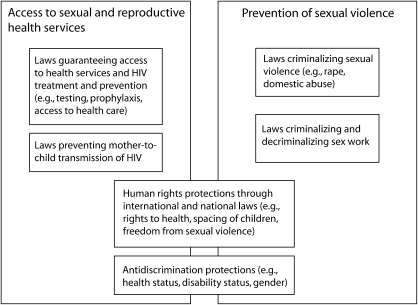

Here we focus on the relationship between law and reproductive and sexual health in two critical areas: (1) access to reproductive health services by women and men living with HIV/AIDS or at risk of contracting HIV and (2) constraints on sexual violence and exploitation, which perpetuate the spread of HIV and its negative effects. We formulate several recommendations for how the law can more effectively promote reproductive and sexual health in the face of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Figure 1 illustrates how different areas of law affect efforts to address reproductive and sexual health issues relating to HIV/AIDS.

FIGURE 1.

Application of law to reproductive and sexual health in the context of HIV/AIDS.

ACCESS TO REPRODUCTIVE SERVICES

Protection of reproductive and sexual health for persons living with HIV/AIDS and those at risk of contracting the virus is predicated on the recognition of individual reproductive and sexual rights and other human rights under the law. Pursuant to these rights, women must (1) be able to make reproductive health decisions without coercion; (2) receive necessary prenatal, delivery, and postpartum health care and treatment; and (3) have the means and information to prevent perinatal transmission. All persons should be given access to necessary sexual health information, including information about sexuality and HIV transmission, and tools to reduce transmission of HIV, such as male12 and female condoms.13

Reproductive Rights

Reproductive and sexual rights are protected human rights, guaranteed under international conventions. These include the right to health,14 to determine the number and spacing of children,15 and to be protected from sexual violence,16 among others.17 Countries that fail to protect human rights often undercut the ability of individuals to procure necessary health services.

National laws vary considerably in their recognition of reproductive rights in the context of HIV/AIDS. The South African constitution, for example, establishes the right of individuals “to make decisions concerning reproduction,” which encompasses decisions on prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care; family planning; prevention and treatment of reproductive tract and sexually transmitted infections; and abortion.18 Several countries in Asia and elsewhere have implemented national policies, but not laws, that support reproductive rights and integrate HIV services and family planning and reproductive health services.19 However, many countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America continue to significantly restrict reproductive rights. Laws limiting access to abortion, contraception, and sexual education, for example, negatively affect women living with HIV. They may suffer the sequelae of unsafe, illegal abortions or face the difficult choice between abstinence and the risk of transmitting HIV to a sexual partner.20

Discrimination

Discrimination that interferes with access to HIV-related health services is a major barrier to good reproductive health for persons living with HIV/AIDS. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has defined HIV discrimination as “[a]ny measure entailing an arbitrary distinction among persons depending on their confirmed or suspected HIV serostatus or state of health.”21 Widespread discrimination against HIV-positive patients in health care settings through direct denials of care or health insurance has been observed in North America,22 Europe,23 Africa,24 Asia,25 and Latin America and the Caribbean.26 Such discrimination also undermines HIV prevention and treatment efforts. Individuals may forgo testing, fail to seek information about how to protect themselves from HIV infection, or shun the health care system altogether to avoid the potential personal, social, and economic consequences of an HIV or AIDS diagnosis.27 Women living with HIV may face general and gender-specific discrimination and stigma that limit their access to reproductive and sexual health services.28

International human rights law, many national constitutions, and other laws prohibit discrimination based on HIV status.29 A 2006 UNAIDS report found that 61% of countries reported having laws that protected persons living with HIV from discrimination.30 Some countries (e.g., the Philippines,31 Cambodia,32 and South Africa33) have explicitly banned HIV discrimination through legislation. The Philippines has adopted a targeted approach, proscribing “discrimination, in all its forms and subtleties, against individuals with HIV or persons perceived or suspected of having HIV” and specifically banning discrimination in hospitals and health institutions.34 More often, HIV and AIDS are not mentioned specifically in antidiscrimination provisions, such as the US Americans with Disabilities Act.35 Rather, these laws forbid discrimination based on “other status,” “health status,” or “disability,” which have been further interpreted to include HIV status, AIDS, and related health conditions by international declarations,36 legislative explanations,37 and court decisions.38

Reproductive and Sexual Health Care and Services

Basic health care and a range of services are fundamental to reproductive and sexual health. For example, availability of methods of prevention such as male and female condoms is critical to a comprehensive, effective, and sustainable approach to HIV prevention and to maintaining sexual health during the pandemic. High-quality, low-cost condoms can greatly reduce the risk of HIV transmission with proper and consistent use.39

Approaches to condom access differ around the world. Some countries have enacted laws and policies that support accessibility and availability of condoms.40 Others perpetuate inaccessibility by failing to allocate resources for condoms, restricting advertising and education campaigns, or criminalizing their possession. The United States has been strongly criticized for limiting access to condoms by requiring 33% of prevention funding under its President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief program to be used for abstinence-only education.41 Some religious hierarchies have constrained efforts to expand access to condoms and sexual education, particularly the Catholic Church, which objects to condom use.42

Criminalization of condoms deters sex workers and others from using them and consequently increases the incidence of unprotected sex and the risk of infection. In 1999, under China's State Advertisement Law, the government banned all advertisements promoting condom use. China has since changed its approach and now strongly promotes condom use, education, and access.43 A few countries have followed the lead of Thailand and enacted laws that require sex workers to use condoms during sexual intercourse.44

Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV

Pregnant women need access to a panoply of specific reproductive health services to ensure the well-being of mother and fetus. According to the United Nations Population Fund and the World Health Organization, a pregnant woman should have access to family planning services, abortion services, prenatal counseling and care, professional delivery care, and postpartum HIV counseling and treatment for herself and her child. Although some laws in some countries guarantee access to these services generally, few laws and policies specify access to each of these important services. As a result, these services are not universally available.45

Without intervention, the risk that a pregnant woman with HIV will transmit the virus to her fetus in the womb or during childbirth ranges from 15% to 30%. The risk of transmission rises to 20% to 45% if the mother breastfeeds her infant.46 Peripartum administration of antiretroviral drugs to the mother, the infant, or both is a cost-effective strategy that can reduce the risk of transmission to less than 2%.47 The efficacy of this treatment regimen in containing HIV infection and limiting mother-to-child transmission has led many lawmakers and health policy experts to recommend widespread testing of pregnant women for HIV.48

At least four models of HIV screening have been used with pregnant women: mandatory testing, opt-out screening, opt-in screening, and voluntary screening. Although some countries have imposed mandatory testing, this approach has been widely condemned for its interference with pregnant women's autonomy. UNAIDS, the World Health Organization, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention support routinely offering HIV testing to all pregnant women as a part of antenatal care (opt-out screening).49 Under this policy, physicians initiate HIV testing as part of the routine panel of prenatal tests unless a woman declines the test. Voluntary, informed consent must be obtained. Pregnant women should receive oral or written information on the clinical and prevention benefits of testing, the right to refuse, follow-up services (posttest counseling, medical care, and psychosocial support), and the importance of partner notification in the event of a positive test outcome. Several countries, including Botswana, have adopted the opt-out approach through legislation.50

An alternative approach, opt-in HIV testing for pregnant women, guarantees counseling as part of the prenatal care program and ensures that a patient “will not be denied prenatal care by the health care provider or at the health care facility because [she] refuses to have a test performed.”51 Some jurisdictions use another voluntary screening model, in which a pregnant woman must affirmatively request an HIV test via specific informed consent.52

A major question is whether pregnant women who test positive will have full access to treatment before, during, and after childbirth. Access to antiretroviral drugs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission is limited in many countries. However, South African women denied access to treatment to prevent mother-to-child transmission succeeded in securing that treatment through litigation.53

SEXUAL VIOLENCE AND EXPLOITATION

Sexual violence, harassment, and exploitation affecting women, children, and other vulnerable persons are major factors in the spread of HIV/AIDS globally. Gender violence and sexual harassment against women heighten their risk of contracting HIV in several ways: (1) coercive sex often causes injuries that increase the risk of infection; (2) social barriers deter women from resisting unwanted, unprotected sexual encounters; (3) psychological fears prevent women from seeking protection or treatment; and (4) economic realities limit women's ability to seek treatment or avoid risky sexual behaviors.

International human rights law requires nations to ensure that women are not subjected to gender violence.54 Laws in most countries protect women from sexual violence by criminalizing prostitution, rape, domestic abuse, and sexual harassment.55 However, meaningful legal protections may still fail to address various facets of gender violence. Structural barriers embedded in gender bias, social stigma, and cultural norms may discourage women from reporting acts of sexual violence, especially instances of marital rape.56 Some countries criminalize marital rape—examples are Mexico,57 Nepal,58 and Zimbabwe59—but others do not. In India, a husband who engages in nonconsensual sex with his wife is not guilty of rape if she is older than 15 years.60 Even when sexual violence is reported and prosecuted, the punishment may be perfunctory.61

Individuals in many societies who have HIV/AIDS or who have lost spouses or parents to the disease are vulnerable to sexual and economic exploitation. In a struggle to survive or by physical coercion, tens of millions of persons have become commercial sex workers,62 substantially increasing their exposure to sexual abuse, discrimination, and HIV infection. The effect on children is especially profound. UNICEF estimates that 1.2 million children are trafficked each year for prostitution or bonded labor.63 Multiple international laws and agreements prohibit the use of children in prostitution, other sexual activity, and pornography, regardless of consent.64 Many countries’ laws reflect these international principles by criminalizing child trafficking, harmful child labor practices,65 and other exploitive activities. Nigeria's National Policy on HIV/AIDS, for example, requires the government to protect vulnerable children from “all forms of abuse including violence, exploitation, discrimination, trafficking, and loss of inheritance.”66

National or regional laws addressing commercial sex work among women, children, and others who may solicit work informally or through organized prostitution reflect varying cultural norms. Laws addressing commercial sex work vary widely:

Some countries—for example, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Poland, and Slovenia—fail to legislatively address the practice altogether. In these places, sex work is not explicitly prohibited, but workers may still be selectively targeted, harassed, and abused via prosecution for various infractions, such as loitering, vagrancy, breach of public order, or lack of appropriate documentation (e.g., passports, residency permits).67

Some countries—for example, Australia, Latvia, Brazil, Greece, Kenya, and Bangladesh—permit informal sex work but seek to regulate its practice through worker licensure, mandatory health screenings, and safe sex requirements.68

Other countries—examples include many countries of the developing world and the Middle East, as well as most jurisdictions in the United States—prohibit sex work by criminalizing related activities, such as solicitation, exchange of sex for money, management of sex workers, and procurement.69

Laws criminalizing sex work, by providing a legislative deterrent, are thought to reduce the incidence of sex work. These laws are meant to reduce the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases among sex workers, whose rates of HIV infection typically are significantly higher than those of the general population.70 However, criminalizing sex work, although it may reflect social norms in many countries, can actually derail efforts to reach sex workers through public health interventions.71

Fear of prosecution, stigmatization, and discrimination keep sex workers from accessing appropriate public health services or availing themselves of legal protections against rape and sexual violence. Their claims of sexual violence are often disregarded or dismissed because of discrimination. In effect, criminalization drives commercial sex work underground. With limited treatment options, scant information on the risks of HIV infection, and their own inability to negotiate safer sex, millions of commercial sex workers are highly at risk of contracting (and exposing others to) HIV.

For these reasons, UNAIDS72 and other international organizations have supported the decriminalization of commercial sex work that does not involve victimizing individuals. In 2003, New Zealand decriminalized prostitution (for persons older than 18 years) but required that all reasonable steps be taken to limit transmission of infections.73 Additional protective measures to promote the public's health while allowing commercial sex work include (1) creating tolerance zones, or local areas where sex work is permissible; (2) periodically testing for sexually transmitted infections and registering commercial sex workers who fulfill testing requirements; (3) requiring safe sex through the provision of condoms by establishments, as initially mandated in Thailand74 and now in other countries (e.g., Cambodia, Dominican Republic, Vietnam, China, Myanmar, and the Philippines)75; (4) ensuring proper storage and handling of condoms, sex toys, and other equipment; (5) training commercial sex workers in the effective use of personal protection equipment, conflict management, and substance abuse awareness; and (6) granting traditional employment rights (e.g., occupational protections, workers’ compensation, sick leave) to commercial sex workers in organized systems to further their health and safety.

Protecting commercial sex workers also entails decriminalizing victims of international and domestic trafficking. Historically, victims of trafficking were seen as criminals subject to prosecution for prostitution, illegal entry, and falsification of documents and were sometimes forced to testify against traffickers. In recognition of serious human rights abuses underlying these practices, the United Nations,76 Council of Europe,77 United States,78 and other international organizations and states have since 2000 increasingly characterized trafficked persons as victims rather than criminals. This enables them to seek legal redress, medical aid, legal assistance, and temporary or permanent residence in some countries, such as the United States, Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands.79

DISCUSSION

Our assessment of law, reproductive and sexual health, and HIV/AIDS identifies opportunities for and barriers to prevention and treatment. We support several broad initiatives to foster the role of law in checking the trajectory of the HIV/AIDS pandemic among women and children: widespread assessment of HIV laws and policies, expansion of legally protected access to HIV/AIDS-related health services, and universal implementation of human rights and antidiscrimination laws.

International organizations and states should undertake a detailed review of their legal frameworks related to HIV/AIDS and reproductive and sexual health, applying the review framework suggested by UNAIDS and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.80 In most of the countries we reviewed, the laws addressing reproductive and sexual health and HIV/AIDS were vague, insufficient, or in violation of international human rights standards. Even countries that have a fairly well-defined legal structure would benefit from a careful review. Systematic review at the national level would help to identify areas of law and policy that need strengthening or revision. Further, such assessments would inform future research into the effectiveness of legal and policy approaches to stemming HIV/AIDS.

Access to Services

Access to reproductive and sexual health services for persons living with HIV/AIDS should be an explicit legal right. This is not yet the case in most countries. Legislation and regulations can require or encourage the government and the private sector to (1) expand access to protective technologies, such as male and female condoms, and continue to develop new technologies, such as effective microbicides81; (2) disseminate information about reproductive and sexual health; (3) develop family planning and prenatal care services that integrate HIV testing and treatment; and (4) fund additional reproductive health services to improve access.

Laws that limit access to condoms, criminalize their possession, or restrict information about their effective use in preventing HIV transmission should be amended because they undermine public health objectives and infringe individual rights. Interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission should focus on the health of both mother and fetus.82 Mandatory screening of pregnant women is counterproductive, but routine screening is acceptable provided it encompasses explicit provisions to obtain informed consent before testing, to allow a woman to opt out of the test, and to protect her privacy. Privacy protections help ensure that test results are not disclosed without patient consent and cannot be used to deny health care, health insurance, or child custody.83

Human Rights Protections

Legislation should be grounded in human rights and explicitly provide safeguards against discrimination based on HIV status, gender, or reproductive status. The international community and many countries recognize the positive correlation between respecting human rights and preventing HIV/AIDS,84 as illustrated in the 2001 Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS.85 Unfortunately, adherence to this commitment is far from universal. In many countries, the human rights of persons at risk of contracting, or already living with HIV/AIDS, continue to be infringed or ignored.

In many countries, HIV-infected women are subject to laws and informal practices that restrict their reproductive freedom. The law should recognize that all people are entitled to the highest attainable standard of reproductive and sexual health; the ability to determine the number, timing, and spacing of their children; and access to sufficient information to make informed decisions on these issues.

National governments should affirm their commitment to these rights by ratifying and implementing the provisions of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.86 The United States has signed but not ratified this convention. Comprehensive legal strategies are needed to empower women to access reproductive health services. Economic and educational opportunities for women and girls are also required to eliminate the economic dependency that contributes to gender violence and exploitation, creates barriers to accessing reproductive health care, and fuels the spread of HIV infection.

Antidiscrimination and Protective Provisions

Laws should expressly protect against discrimination based on HIV status. HIV-infected persons should be guaranteed equal access to health care generally and to reproductive and sexual health services specifically. Antidiscrimination protections should prohibit rationing of health care services on the basis of HIV status or gender, marital, or pregnancy status. Similarly, laws should specifically prohibit gender violence and sexual exploitation of women and children. Recognizing that vulnerable persons are victims, rather than perpetrators, of violence and exploitation is consistent with good public health practice and human rights.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has imposed substantial burdens on sexual and reproductive health. The establishment and enforcement of clear legal provisions could alleviate some of this burden provided that laws promote human rights, proscribe discrimination against women and against people living with HIV/AIDS, guarantee access to reproductive and sexual health services, and protect against sexual violence and exploitation.

Acknowledgments

Some of the initial funding for this research was provided by the World Bank Group.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Tamar Dolcourt and Kaitlin McKenzie, students at the Wayne State University Law School, and Gayle Nelson, a student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. We thank Rudolph Van Puymbroeck and Katharina Gamharter, formerly of the World Bank, for their support and insights.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required for this study because it did not involve human participants.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, research, drafting, and revisions of this article.

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO), AIDS Epidemic Update, (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS and WHO, December 2007), 1.

- 2. Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator, The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: U.S. Five-Year Global HIV/AIDS Strategy, (Washington, DC: US Department of State, February 2004), 17, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/29831.pdf (accessed July 16, 2008)

- 3. UNAIDS and WHO, AIDS Epidemic Update, 1. Approximately 15.4 million women worldwide are estimated to be infected with HIV.

- 4. Ibid., 8.

- 5.Rebecca J Cook, et al. , Reproductive Health and Human Rights: Integrating Medicine, Ethics, and Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 6. UNAIDS, Gender and HIV/AIDS (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 1998)

- 7. UN Population Fund (UNFPA), “Reproductive Health Fact Sheet,” 2005, http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2005/presskit/factsheets/facts_rh.htm (accessed July 13, 2008)

- 8. New York University Medical Center, “HIV Info Source,” 2007, http://www.hivinfosource.org/hivis/hivbasics/women (accessed July 13, 2008)

- 9. UNAIDS, 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2006), chap. 3, http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp (accessed July 13, 2008)

- 10. UNAIDS and WHO. AIDS Epidemic Update, 8; Ralf Jurgens and Jonathan Cohen, Human Rights and HIV/AIDS—Now More Than Ever (New York, NY: Open Society Institute September 2007), 2, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/law/articles_publications/publications/human_20071017/english_now-more-than-ever.pdf (accessed July 16, 2008)

- 11.Lance Gable, et al. , Legal Aspects of HIV/AIDS: A Guide for Policy and Law Reform (Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO and UNFPA, Position Statement on Condoms and HIV Prevention (Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2004), http://www.unfpa.org/upload/lib_pub_file/343_filename_Condom_statement.pdf (accessed July 13, 2008)

- 13. UNAIDS, The Female Condom: A Guide for Planning and Programming (Geneva, UNAIDS, 2000), http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/jc301-femcondguide_en.pdf (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 14. UN, International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, art. 12, UN document A/6316 (New York, NY: UN, 1966); UN, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, art. 12, http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 15. Ibid., art. 16(1)(e)

- 16. Ibid., arts. 5 (a), 6.

- 17. Center for Reproductive Rights, Reproductive Rights Are Human Rights (New York, NY: Center for Reproductive Rights, 2003)

- 18. South Africa Constitution, sec. 12(2)(a), http://www.info.gov.za/documents/constitution/1996/96cons2.htm#12 (accessed July 16, 2008)

- 19. Center for Reproductive Rights, Women of the World: Laws and Policies Affecting Their Reproductive Lives in East and Southeast Asia (New York, NY: Center for Reproductive Rights, 2005)

- 20. UNFPA and WHO, Sexual and Reproductive Health of Women Living with HIV/AIDS: Guidelines on Care, Treatment and Support for Women Living with HIV/AIDS and Their Children in Resource-Constrained Settings (Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2006), http://www.unfpa.org/publications/detail.cfm?ID=297 (accessed July 14, 2008.

- 21. UNAIDS, Protocol for the Identification of Discrimination Against People Living with HIV (Geneva, Switzerland, UNAIDS, 2000)

- 22.Mark A Schuster, et al., “Perceived Discrimination in Clinical Care in a Nationally Representative Sample of HIV-Infected Adults Receiving Health Care,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 20, no. 9(September 2005): 807–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United Kingdom National AIDS Trust, HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination: Proposals from the National AIDS Trust for the Government Action Plan (London: United Kingdom National AIDS Trust, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Augustine D Asante, “Scaling Up HIV Prevention: Why Routine or Mandatory Testing Is Not Feasible for sub-Saharan Africa,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85, no. 8 (August 2007): 569–648, http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/8/06-037671/en/index.html (accessed July 14, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniel D Reidpath, Kit Yee Chan, “HIV Discrimination: Integrating the Results from a Six-Country Situational Analysis in the Asia Pacific. AIDS Care 17, supp. 2 (2005): S195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan American Health Organization, Understanding and Responding to HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma and Stigma and Discrimination in the Health Sector (Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pan American Health Organization, HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma.

- 28. UNAIDS, Comparative Analysis: Research Studies From India and Uganda, HIV and AIDS-related Discrimination, Stigmatization and Denial (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2000); International Center for Research on Women, HIV/AIDS Stigma: Finding Solutions to Strengthen HIV/AIDS Programs (Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women, 2006)

- 29. UN, International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, 1976, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 30. UNAIDS, 2006 Report.

- 31. Philippines AIDS Control and Prevention Act of 1998, HIV/AIDS Impact on Education Clearinghouse, http://hivaidsclearinghouse.unesco.org/ev_en.php?ID=2050_201&ID2=DO_TOPIC (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 32. Government of Cambodia, Law on the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS, International Labor Organization (ILO), http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/trav/aids/laws/cambodia1.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 33. South Africa, Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act No 4 of 2000, Schedule 5. (c), http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/acts/2000/2000-04.pdf (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 34. Philippines AIDS Control and Prevention Act, supra note 33, sec. 40.

- 35. Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 (2008)

- 36. UN Commission on Human Rights, The Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Resolution (AIDS), Res. 49/1999, 55th Sess., E/CN.4/RES/1999/49, http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/(Symbol)/E.CN.4.RES.1999.49.En?Opendocument (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 37. United Kingdom Office of Public Sector Information, Disability Discrimination Act of 2005 (OPSI 2005), http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/20050013.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 38. Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624 (1998)

- 39. USAID, “USAID: HIV/STI Prevention and Condoms,” May 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids/TechAreas/prevention/condomfactsheet.html (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 40. South Africa Ministry of Health, “HIV/AIDS/STD Strategic Plan for South Africa 2000–2005,” http://www.info.gov.za/otherdocs/2000/aidsplan2000.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008). The South African plan provides for condom distribution in nontraditional places such as truck stops and in all government buildings.

- 41. US Government Accountability Office, Global Health: Spending Requirement Presents Challenges for Allocating Prevention Funding Under the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, GAO-06-395 (Washington, DC: GAO, 2006), http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d06395.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 42.Pope Paul, VI, Humanae Vitae [On the Regulation of Birth] (encyclical letter), 1968, http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Paul06/p6humana.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 43. China AIDS Survey, “China HIV/AIDS Policy and Regulations Chronology,” 2004, http://www.casy.org/chron/poilcy.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 44. UNAIDS, “Evaluation of the 100% Condom Programme in Thailand: Case Study,” 2000, http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC275-100pCondom_en.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008); WHO, “Experiences of 100% Condom Use Programme in Selected Countries of Asia,” 2004, http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/pub_9290610921.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 45. UNFPA and WHO, Sexual and Reproductive Health.

- 46.Kevin M De Cock, et al., “Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission in Resource-Poor Countries: Translating Research into Policy and Practice, JAMA 283 (2000): 1175–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alejandro Dorenbaum, et al. , “Two-Dose Intrapartum/Newborn Nevirapine and Standard Antiretroviral Therapy to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission: A Randomized Trial,” JAMA 288 (2002): 189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. WHO, Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants (Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2006), http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/guidelinesarv/en/index.html (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 49. UNAIDS and WHO, “Policy Statement on HIV Testing,” June 2004, http://data.unaids.org/UNA-docs/hivtestingpolicy_en.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 50.Stuart Rennie, Frieda Behets, “Desperately Seeking Targets: The Ethics of Routine HIV Testing in Low-Income Countries,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84, no. 1 (2006): 53; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Introduction of Routine HIV Testing in Prenatal Care: Botswana, 2004,” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 53 (Nov. 26, 2004): 1083–86 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Md. Code Ann., Health-Gen. §18-338.2 (2008), http://mlis.state.md.us. (The Maryland legislature passed a bill in April 2008 that established more stringent pre-test informed consent requirements. See Maryland Senate Bill 826, passed April 24, 2008, http://mlis.state.md.us/2008rs/billfile/SB0826.htm [accessed July 17, 2008].)

- 52.Frank Baiden, et al. , “Review of Antenatal-Linked Voluntary Counseling and HIV Testing in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons and Options for Ghana,” Ghana Medical Journal 39, no. 1 (2005): 8–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Minister of Health v. Treatment Action Campaign, CCT 8/02 2002(5) SA 721(CC) par 135, http://www.constitutionalcourt.org.za/uhtbin/cgisirsi/20080714235125/SIRSI/0/520/J-CCT8-02A (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 54. UN Development Programme, “Dying of Sadness: Gender, Sexual Violence and the HIV Epidemic,”1999, http://www.undp.org/hiv/publications/gender/violencee.htm (accessed July 14, 2008); Amnesty International, “Women, HIV/AIDS, and Human Rights,” Nov. 24, 2004, http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT770842004 (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 55. International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, “Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence Against Women in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice,” March 1999, http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/Compendium.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 56.Saurabh Mishra, Sarvesh Singh, Marital Rape—Myth, Reality, and Need for Criminalization, Feminist Studies and Law Relating to Women/Criminal/Sexual Offences (Lucknow, India: Eastern Book Company, 2003), http://www.ebc-india.com/lawyer/articles/645.htm (accessed July 14, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elisabeth Malkin, Ginger Thompson, “Mexican Court Says Sex Attack by a Husband Is Still a Rape,” New York Times, November 17, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Forum for Women, Law and Development v. Ministry of Law, 55 Nepali Sup. Ct. 2058 (2002), http://www.fwld.org.np/marrape.html (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 59. Zimbabwe, Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act (Act 23/2004), http://www.kubatana.net/html/archive/legisl/050603crimlaw.asp?sector=LEGISL&year=0&range_start=1 (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 60.Mandeep Dhaliwal, “Creation of an Enabling and Gender-Just Legal Environment as a Prevention Strategy for HIV/AIDS among Women in India,” Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Newsletter 4, no. 2/3 (1999): 86–89 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Human Rights Watch, “Policy Paralysis: A Call for Action on HIV/AIDS-Related Human Rights Abuses Against Women and Girls in Africa,” http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/africa1203/9.htm#_Toc56508501 (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 62. UNAIDS, At Risk and Neglected… Sex Workers. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2006), 105–10; ILO, The End of Child Labour: Within Reach Global Report Under the Follow-up to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (Geneva, Switzerland: ILO, 2006), http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/ipec/about/globalreport/2006/index.htm (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 63. UNICEF, “Excluded and Invisible: The State of the World's Children,” 2006, http://www.unicef.org/sowc06/pdfs/sowc06_fullreport.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 64. Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General Comment 3: HIV/AIDS and the Rights of the Child, para. 36,” 2003, http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(symbol)/CRC.GC.2003.3.En?OpenDocument (accessed July 14, 2008); Annemarie Meisling, Rudolf V. Van Puymbroeck, and Tara O'Connell, “Legal Protection of Children Orphaned or Made Vulnerable by HIV/AIDS: International and Selected Domestic Law,” (unpublished document on file with the authors and World Bank, 2005)

- 65. ILO, End of Child Labour.

- 66. Federal Government of Nigeria, “National Policy on HIV/AIDS,” 2003, HIV/AIDS Impact on Education Clearinghouse, http://hivaidsclearinghouse.unesco.org/ev_en.php?ID=4239_201&ID2=DO_TOPIC (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 67. Central and Eastern European Harm Reduction Network , Sex Work, HIV/AIDS, and Human Rights in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Vilnius, Lithuania: Open Society Institute, 2005), 35–41, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/health/focus/sharp/articles_publications/publications/sexwork_20051018/sex%20work%20in%20ceeca_report_2005.pdf (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 68. Gable et al., Legal Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 101–8.

- 69. Ibid.

- 70. UNAIDS, “Sex Work and HIV/AIDS: Technical Update,” 2002, http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub02/JC705-SexWork-TU_en.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michael L Rekart. “Sex-Work Harm Reduction,” Lancet 366 (2005): 2123–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.UNAIDS and Inter-Parliamentary Union, Handbook for Legislators on HIV/AIDS, Law and Human Rights: Action to Combat HIV/AIDS in View of Its Devastating Human, Economic and Social Impact (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS/IPU, 1999), http://www.ipu.org/PDF/publications/aids_en.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008); UNAIDS, “Sex Work and HIV/AIDS.”

- 73. New Zealand, Prostitution Reform Act, 2003, http://www.justice.govt.nz/plr/ (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 74.UNAIDS, “Evaluation of the 100% Condom Programme.”

- 75.WHO, “Experiences of 100% Condom Use Programme.”

- 76. “UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children,” 2000, http://untreaty.un.org/English/notpubl/18-12-a.E.doc (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 77. Council of Europe, “Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings,” http://www.coe.int/T/E/human_rights/trafficking/PDF_Conv_197_Trafficking_E.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 78. US Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, “Model Law to Combat Trafficking in Persons,” US Department of Justice, http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/crim/model_state_law.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 79.Mohamed Y Mattar, “Incorporating the Five Basic Elements of Model Antitrafficking in Persons Legislation in Domestic Laws: From the United Nations Protocol to the European Convention,” Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law 14 (2006): 357–420 [Google Scholar]

- 80. UNAIDS and Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights, Consolidated Version (Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS and UNHCHR, 2006)

- 81. MDS Working Groups, The Microbicide Development Strategy (Silver Spring, MD: Alliance for Microbicide Development, August 2006), http://www.microbicide.org/microbicideinfo/reference/MDS.FINAL.10Aug06.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 82. Center for Reproductive Rights, Pregnant Women Living with HIV/AIDS: Protecting Human Rights in Programs to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (New York, NY: Center for Reproductive Rights, 2005), www.crlp.org/pdf/pub_bp_HIV.pdf (accessed July 14, 2008)

- 83.Leslie E Wolf, Bernard Lo, Lawrence O Gostin, “Legal Barriers to Implementing Recommendations for Universal, Routine Prenatal HIV Testing,” Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 32 (2004): 137–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. UNAIDS and UNFPA, New York Call to Commitment Linking HIV/AIDS and Sexual and Reproductive Health (New York, NY: UNAIDS and UNFPA, 2004), http://www.unfpa.org/publications/detail.cfm?ID=195&filterListType=3 (accessed July 17, 2008)

- 85. UN General Assembly, Declaration of Commitment on HIV/ AIDS, Resolution A/RES/S-26/2, August 2, 2001, http://www.un.org/ga/aids/coverage/FinalDeclarationHIVAIDS.html (accessed July 13, 2008)

- 86. Division for the Advancement of Women, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, States Parties that have signed and ratified the convention, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/states.htm (accessed July 17, 2008)