Abstract

Objective

To quantify the influence of increasing use of health-care services on rising rates of caesarean section in China.

Methods

We used data from a population-based survey conducted by the United Nations Population Fund during September 2003 in 30 selected counties in three regions of China. The study sample (derived from birth history schedule) consisted of 3803 births to mothers aged less than 40 years between 1993 and 2002. Multiple logistic regression models were used to estimate the effect of health-care factors on the odds of a caesarean section, controlling for time and selected variables.

Findings

Institutional births increased from 53.5% in 1993–1994 to 82.2% in 2001–2002, while the corresponding increase in births by caesarean section was from 8.9% to 24.8%, respectively. Decomposition analysis showed that 69% of the increase in rates of caesarean section was driven by the increase in births within institutions. The adjusted odds of a caesarean section were 4.6 times (95% confidence interval, CI: 3.4–11.8) higher for recent births. The adjusted odds were also significantly higher for mothers who had at least one antenatal ultrasound test. Rates of caesarean section in secondary-level facilities markedly increased over the last decade to the same levels as in major hospitals (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The upsurge in rates of births by caesarean section in this population cannot be fully explained by increases in institutional births alone, but is likely to be driven by medical practice within secondary-level hospitals and women’s demand for the procedure.

Résumé

Objectif

Quantifier l’influence du recours accru aux services de santé sur les taux de césarienne en Chine.

Méthodes

Nous avons exploité les données d’une enquête en population menée par le Fonds des Nations Unies pour la population en septembre 2003 dans 30 comtés choisis dans trois régions chinoises. L’échantillon étudié (constitué en fonction de l’historique de l’accouchement) comprenait 3803 naissances survenues chez des mères de moins de 40 ans entre 1993 et 2002. Des modèles de régression logistique multiple ont été utilisés pour estimer l’effet de facteurs liés aux soins de santé sur les probabilités d’accouchement par césarienne, les variables contrôlées incluant notamment la période de naissance.

Résultats

La proportion des naissances en maternité est passée de 53,5% pendant la période 1993-1994 à 82,2% pendant la période 2001-2002, tandis que le taux de naissance par césarienne correspondant augmentait de 8,9 à 24,8%. L’analyse par décomposition a fait apparaître que 69% de l’accroissement des taux de césariennes découlent de l’augmentation du taux de naissance en maternité. Les probabilités ajustées d’accouchement par césarienne étaient 4,6 fois plus élevées (intervalle de confiance à 95%, IC : 3,4-11,8) pour les naissances récentes. Ces probabilités ajustées étaient aussi significativement supérieures pour les mères ayant subi au moins une échographie anténatale. Les taux d’accouchement par césarienne dans des établissements de soins de santé secondaire ont augmenté notablement sur la dernière décennie, jusqu’à atteindre des niveaux analogues à ceux des grands hôpitaux (p < 0,001).

Conclusion

Les très fortes augmentations des taux de naissance par césarienne dans la population considérée ne peuvent s’expliquer totalement par l’accroissement des taux des naissances en maternité, mais sont aussi probablement imputables aux pratiques médicales des établissements de soins de santé secondaire et à la demande des femmes.

Resumen

Objetivo

Cuantificar la influencia del aumento del uso de los servicios de salud en el incremento de las tasas de cesárea en China.

Métodos

Los datos empleados proceden de una encuesta poblacional llevada a cabo por el Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas durante septiembre de 2003 en 30 circunscripciones de tres regiones de China. La muestra estudiada (obtenida a partir de una lista de historias genésicas) abarcaba 3803 partos de madres de menos de 40 años registrados entre 1993 y 2002. Se usaron modelos de regresión logística múltiple para calcular el efecto de diversos factores relacionados con la salud en la probabilidad de cesárea, controlando el tiempo y otras variables.

Resultados

Los partos en instituciones aumentaron de un 53,5% en 1993-1994 al 82,2% en 2001-2002, y entre esas fechas los nacimientos por cesárea aumentaron del 8,9% al 24,8%. El análisis de descomposición mostró que el 69% del aumento de las tasas de cesárea se debió al incremento de los nacimientos en instituciones. La probabilidad ajustada de cesárea fue 4,6 veces (intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95%: 3,4-11,8) mayor para los nacimientos recientes. La probabilidad ajustada fue también significativamente mayor para las madres que se habían sometido al menos a una ecografía prenatal. Las tasas de cesárea en los establecimientos de nivel secundario aumentaron sensiblemente durante el último decenio, hasta alcanzar los mismos valores que en los hospitales principales (P < 0,001).

Conclusión

El repunte de las tasas de parto por cesárea en esta población no puede explicarse sólo por el aumento de los nacimientos en instituciones. Probablemente hay que tener también en cuenta la evolución del ejercicio de la medicina en los hospitales de nivel secundario y la demanda de ese procedimiento por las mujeres.

ملخص

الغرض

استەدفت ەذە الدراسة قياس أثر تـزايد الاستفادة من خدمات الرعاية الصحية على تـزايد معدلات إجراء الجراحة القيصرية في الصين.

الطريقة

استخدمنا في ەذە الدراسة بيانات مستمدة من المسح السكاني الذي أجراە صندوق الأمم المتحدة للسكان في أيلول/سبتمبر 2003 في 30 بلداً منتقاة من ثلاث مناطق في الصين. وقد تكوَّنت عيِّنة الدراسة المأخوذة من سجلات تاريخ الولادات من 3803 ولادات لأمەات تقل أعمارەن عن 40 عاماً، وذلك في المدة من 1993 إلى 2002. واستُخدمت نماذج التحوف اللوجستي المتعدِّد لتقدير تأثير عوامل الرعاية الصحية على احتمال إجراء الجراحة القيصرية، مع النظر بشكل مستقل إلى الفتـرة الزمنية ومتغيرات أخرى منتقاة.

الموجودات

ازدادت نسبة الولادات في المؤسسات الصحية من 53.5% في الفتـرة 1993 – 1994 إلى 82.2% في الفتـرة 2001 – 2002، في حين ازدادت نسبة الولادات التي تمت بالجراحة القيصرية من 8.9% في 1993 – 1994 إلى 24.8% في 2001 – 2002. وقد بيَّن التحليل التفصيلي أن 69% من الزيادة في معدلات الولادة القيصرية نتجت عن ازدياد الولادات التي تمت داخل المؤسسات. وكانت الأرجحية المصحَّحة لإجراء الولادة القيصرية أعلى بنسبة 4.6 أضعاف في الولادات التي تمت حديثاً (عند فاصلة ثقة 95%، إذْ تـراوحت القيم من 3.4 إلى 11.8). كما كانت الأرجحية المصحَّحة أعلى بدرجة مەمة إحصائياً لدى الأمەات اللاتي أُجري لەن اختبار واحد على الأقل بالموجات الفائقة الصوت قبل الولادة. ولوحظ أيضاً تـزايد واضح في معدلات الولادة بالجراحة القيصرية في مرافق المستوى الثانوي خلال العقد الأخير، إذْ وصلت إلى نفس المستويات التي لوحظت في المستشفيات الرئيسية (قيمة الاحتمال

P < 0.001).

الاستنتاج

إن الارتفاع المفاجئ في معدلات الولادة بالجراحة القيصرية في ەذە المجموعة السكانية لا يمكن أن يُعزى بشكل كامل إلى الزيادة في معدلات الولادة في المؤسسات، وإنما يُُعزى على الأرجح إلى طبيعة الممارسة الطبية داخل مستشفيات المستوى الثانوي وإلى إقبال النساء على الولادة بالجراحة القيصرية.

Introduction

Rates of caesarean section in many countries have increased beyond the recommended level of 15%,1 almost doubling in the last decade, especially in high-income areas such as Australia, France, Germany, Italy, North America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK).2–7 Similar trends have also been documented in low-income countries such as Brazil, China and India, especially for births in private hospitals.8–12 Advanced health-care technologies are becoming more widely available in different regions of China. Following health-care reforms introduced in the 1990s, a large proportion of Chinese women, including those from the less-developed western region, now seek early antenatal and delivery care in health institutions. The number of caesarean-section births has increased sharply especially in the eastern region, which covers the major cities of Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin.12 Recent evidence also shows increasing demand for caesarean section among young, educated women residing in urban areas.13

Many Chinese couples now delay childbearing, aim to have not more than one birth experience and opt for delivery by caesarean section to avoid pain.13,14 Data from hospital-based studies in urban China showed rates of caesarean section of between 26% and 63% during the late 1990s.15–18 Another population-based study reported a substantial increase during the last three decades, from 4.7% to 22.5%.12 These trends are expected to persist in view of the unparalleled economic growth and rapid expansion of private health care and health insurance systems across China. Apart from the clinical indications for caesarean section – breech presentation, dystocia and suspected fetal compromise – there is growing evidence that many women choose delivery by caesarean section for personal reasons, particularly in profit-motivated institutional settings that may provide implicit or explicit encouragement for such interventions.13,19 The goal of our research was to quantify the influence of increased overall use of health-care services on rising rates of caesarean section in China. We hypothesized that the increase in institutional births and use of modern obstetric technologies explain the observed increase in rates of caesarean section.

Methods

Data sources

We used data from a population-based survey conducted during September 2003 in 30 selected counties covering all provinces in all three regions of China. The survey was coordinated by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in collaboration with China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission and health ministry. The counties were selected on the basis of planned future participation in UNFPA-linked reproductive health programmes. The sample of countries chosen in the survey was not intended to be nationally representative, but it covers the three regions and represents relatively developed Chinese areas in terms of socioeconomic status. The survey was based on household population records and the design included a stratified multi-stage selection of a sample of women aged 15–49 years. The 30 selected counties defined a population of townships. In the first stage of the analysis, these were stratified by region (eastern, central, western) and by residence (rural or urban). Within each region, 35 townships were selected; this sample was divided between urban and rural strata proportional to the population of women aged 15–49 years, subject to a minimum urban sample of seven townships. At the second stage, four local communities were selected proportional to the population of women aged 15–49 years from each selected township. At the final stage, a systematic random sample of 20 women was selected from a list ordered by age of all women aged 15–49 years within each selected community. This led to a final sample of 8400 women aged 15–49 years from 8400 households (2800 women per region and 80 women from each of the 105 sampled townships).

The survey questionnaire contained a detailed section on birth history (the birth history schedule) that collected information on antenatal care and delivery for each pregnancy. The initial rates of participation were very high, and in the small number of cases where an interview was not obtained, the respondent was replaced by another respondent of the same age. Of 8400 women, 7432 were married at the time of the survey. In the birth history schedule, detailed information was recorded for 11 315 births that occurred between 1971 and 2003. However, for the analysis we considered 3814 births that took place between 1993 and 2002. Additionally, we selected only mothers whose age at delivery was less than 40 years. This age restriction ensured that the cross-sectional sample of mothers aged 15–49 years at the time of the survey properly represented births over a 10-year period. The final selected sample for analysis included 3803 births that took place between 1993 and 2002 among 2829 mothers aged 15–39 years. Nearly 82% of mothers in the selected sample reported having received antenatal care. The proportion of institutional deliveries among the selected sample was 66.2% (n = 3803). Preliminary scrutiny of the data indicated that women from the eastern region, those who lived in urban areas, those who received education to senior high school level or above and those employed in the service or professional sectors were more likely to opt for an institutional delivery. For the detailed analysis, we considered only the 2516 births to 2267 mothers that took place in health-care institutions. Of these 2267 mothers, 89.3% gave birth to one child between 1993 and 2002, 10.4% had two children and less than 1% had three or more children.

Mothers were asked if their deliveries were vaginal or by caesarean section. We consider misreporting to be unlikely as a source of bias, as mothers were not likely to report a normal vaginal birth as a caesarean or vice versa. Those who had a caesarean delivery were also asked whether they had requested the procedure. The individual data were in anonymous format for analysis and ethical approval was not required.

Statistical analysis

Data were weighted to calculate the crude prevalence of caesarean birth – the difference in proportions between weighted and unweighted data was trivial. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to examine the effect of health-care variables on the odds of a caesarean birth. The dependent variable in the regression was mode of institutional delivery (caesarean section coded as indicator category and vaginal birth coded as reference category). The health-care variables considered in the statistical analysis included use of antenatal care and associated specific components of care received during pregnancy. These included ultrasound scanning, measurement of blood pressure, abdominal examination, and clinical tests of liver function, haemoglobin and urine. Other control variables in the analysis included year of birth to control for period effects, mother’s place and region of residence, age at birth, family size, education and occupation. We did not consider the mode of delivery for a previous birth as a control variable since the sample consisted predominantly of prima paras. The variables included in the regression model were screened for problems of multi-collinearity, and variables that were highly correlated with each other were excluded from the model. Additionally, we applied decomposition methods to differentiate the relative contribution of the underlying trends in institutional births to the increase in rates of caesarean section.20 Decomposition techniques incorporate interactive effects between the compositional changes in the variables and explain whether an increase over time in institutional births contributes to an increase in caesarean births.

Results

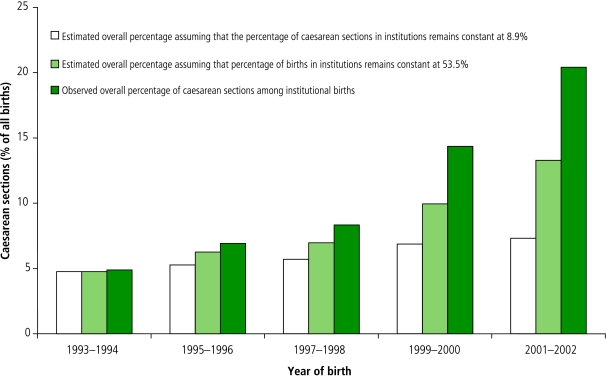

The overall population-level estimate of rates of caesarean section increased in a linear manner from 4.9% in 1993–1994 to 20.4% in 2001–2002 (Table 1). Rates of institutional delivery during these periods were 53.5% and 82.2%, respectively. Within institutional settings, rates of caesarean section increased linearly from 8.9% in 1993–1994 to 24.8% in 2001–2002. Had rates of caesarean section within institutions remained constant at the level of 8.9% observed in 1993–1994, the overall rate of caesarean section would have risen only to 7.3% during 2001–2002 (Fig. 1). Conversely, had the proportion of births that took place in institutional settings remained constant at 53.5%, rates of caesarean section would have increased to only 13% during 2001–2002. The decomposition analyses suggest that 69.0% of the increase in rates of caesarean section was driven by the increase in births within institutions; the increase was particularly notable in the central (78.0%) and eastern (73.7%) regions (results not shown separately). The relative contribution of the underlying trends in institutional births to the increase in deliveries by caesarean was 54.1% in the western region; this indicates that more than 40% of the increase seen in the western region was attributable to factors other than the increase in institutional deliveries. The western region is relatively less developed than other regions, in which large-scale poverty alleviation and maternal and child mortality reduction programmes have been in place since 1999.21,22

Table 1. Trends in caesarean births and institutional births by year and region, 1993–2002.

| Region | Births by caesarean and/or in institutiona | Year of birth |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993–1994 | 1995–1996 | 1997–1998 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | |||

| East | Number of births | 242 | 255 | 194 | 193 | 233 | 1117 |

| Overall CSb (%) | 7.3 | 10.1 | 15.5 | 19.3 | 24.7 | 15.1 | |

| Institutional births (%) | 65.7 | 74.1 | 76.3 | 89.2 | 89.3 | 78.4 | |

| CS within institution (%) | 11.2 | 13.6 | 20.4 | 21.6 | 27.8 | 19.3 | |

| Central | Number of births | 272 | 227 | 236 | 238 | 242 | 1215 |

| Overall CSb (%) | 3.2 | 3.3 | 8.2 | 14.0 | 23.5 | 10.3 | |

| Institutional births (%) | 57.2 | 57.8 | 71.2 | 85.6 | 83.6 | 70.9 | |

| CS within institution (%) | 5.6 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 16.4 | 28.1 | 14.6 | |

| West | Number of births | 372 | 308 | 318 | 232 | 241 | 1471 |

| Overall CSb (%) | 3.9 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 6.7 | |

| Institutional births (%) | 41.7 | 45.8 | 50.3 | 57.4 | 73.2 | 52.1 | |

| CS within institution (%) | 8.8 | 14.1 | 7.1 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 12.8 | |

| All regions | Number of births | 886 | 790 | 748 | 663 | 716 | 3803 |

| Overall CSb (%) | 4.9 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 14.4 | 20.4 | 10.6 | |

| Institutional births (%) | 53.5 | 59.2 | 64.1 | 77.2 | 82.2 | 66.3 | |

| CS within institution (%) | 8.9 | 11.7 | 13.0 | 18.6 | 24.8 | 15.9 | |

CS, caesarean section. a The percentages shown are based on weighted data controlling for mothers aged less than 40 years at delivery. b Population-level estimates.

Fig. 1.

Rates of birth by caesarean section: trends attributed to levels of institutional births and use of caesarean section within institutions, 1993–2002a

a Data shown are controlled for respondents (mothers) aged 40 years at the time of delivery and are based on decomposition analysis.

The trends in rates of caesarean section were further established using regression analysis (Table 2). After controlling for selected health-care, demographic and social factors, the results showed that the odds of an institutional birth during 1999–2002 being by caesarean section were 4.6 times (95% confidence interval, CI: 2.8–7.7) greater when compared with that during 1993–1994 (P < 0.001). The use of ultrasound scanning at least once during the pregnancy had a significant effect on the odds of having a caesarean section; the odds for a caesarean section were 1.6 times greater for women who received antenatal care with at least one ultrasound scan than for those who had received antenatal care with no ultrasound scan. However, mothers who had had no formal antenatal care but who gave birth in a health-care institution were significantly more likely to have undergone a caesarean section. A higher proportion of mothers who gave birth in general hospitals and family planning hospitals at the county level had caesarean sections compared with those who delivered in smaller hospitals, such as township general and family planning hospitals. The county-level hospitals usually cater to a larger population, including referral cases from township-level and other hospitals within a township. The odds of a caesarean delivery were about 2.6 times higher in a maternal and child health (MCH) hospital at the county level than in other small township-level hospitals (P < 0.001). All control variables except parity and place of residence were statistically significant in the regression. The odds of a caesarean section were significantly higher for mothers with only one child when compared to those with more than one birth. About 75% of women who had a caesarean birth had only one child at the time of survey.

Table 2. Likelihood of having a delivery by caesarean section within an institution for 2516 mothers aged less than 40 years.

| Characteristics | Unadjusted proportions | Adjusteda odds ratios (95% confidence intervaI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of birth | |||

| 1993–1994 (reference category) | 8.9 | 1.0 | – |

| 1995–1996 | 11.6 | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 0.155 |

| 1997–1998 | 12.9 | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 0.109 |

| 1999–2000 | 18.8 | 3.5 (2.1–6.0) | 0.000 |

| 2001–2002 | 25.3 | 4.6 (2.8–7.7) | 0.000 |

| ANC componentsb | |||

| At least one ANC component and ultrasound | 14.2 | 1.0 | |

| All selected ANC components and ultrasound | 25.2 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.010 |

| At least one ANC component and no ultrasound | 7.1 | 0.6 (0.4–1.1) | 0.092 |

| Had ANC only at time of delivery | 13.0 | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.431 |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Other c | 7.2 | 1.0 | |

| General hospital | 24.2 | 5.9 (3.8–9.0) | 0.000 |

| Maternal and child health hospital | 19.7 | 2.6 (1.8–3.7) | 0.000 |

| County family planning hospital | 22.1 | 6.5 (3.2–13.1) | 0.000 |

| General hospital, or county family planning hospital and birth between 1999 and 2002 | 29.3 | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 0.000 |

| Constant | NA | –6.663 | 0.000 |

| –2 log-likelihood | NA | 1911 |

ANC, antenatal care clinic; NA, not applicable. a Adjusted for maternal age, family size, occupation and region of residence of mother. b Antenatal care includes measurement of weight, tests on blood, urine and of liver function, abdominal examinations and test for hypertension. c “Other” includes private clinics and township general and family planning hospitals.

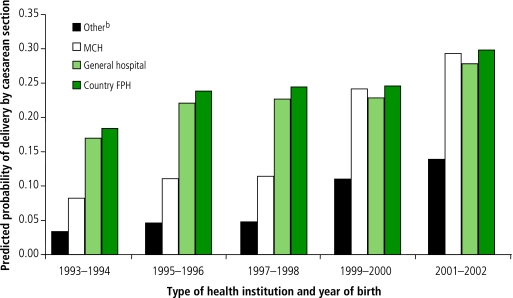

We examined the possibility that there was an interaction effect between place of delivery and year of birth. For reasons of adequate sample size within each category, we merged the big hospitals (general and county-level family planning hospitals) to create the indicator category, and merged other hospitals including MCH hospitals for the reference category. The interaction effect was statistically highly significant. The results showed that the odds of a recent birth being by caesarean section was nearly 60% greater in smaller hospitals when compared with larger hospitals where the levels of caesarean section were already very high. The rise in rates of caesarean section in the township-level and MCH hospitals relative to other larger hospitals is illustrated in terms of adjusted predicted probabilities (Fig. 2). In MCH hospitals, the rate of caesarean section increased from 8.2% during 1993–94 to 29.3% during 2001–02, almost equalling that in the major family planning and general hospitals at the county level.

Fig. 2.

Increase in predicted probability of caesarean section, by type of health institution, 1993–2002a

FPH, family planning hospital; MCH, maternal and child health hospital.

a The predicted probabilities shown are adjusted for health-care, demographic and social variables.

b “Other” includes township hospitals, township family planning hospitals and private clinics.

In the survey, women were asked whether they had requested a caesarean delivery. Among those who had a birth during 2001–2002, 50.7% responded in the affirmative; this compares with an overall figure of 44.7% for the decade preceding the survey. Mothers who resided in urban areas and the western region, those who had senior high school education and above, and those employed in professional and service sectors were more likely to respond in the affirmative to this question (results not shown separately).

Discussion

The increase in rates of caesarean delivery observed over time in our study population was not fully explained by the increase in the rates of institutional birth alone. Instead, they were likely to be driven by the twin pressures of obstetricians favouring recourse to caesarean delivery and women’s demand for the procedure. The analysis demonstrated that use of antenatal care, especially ultrasound scanning, was also associated with a greater likelihood of caesarean delivery. The availability and widespread use of ultrasound scanning indicates the extent of use (medicalization) of antenatal care services by women in the study area and could be either a marker for a type of patient who prefers medical intervention, or a marker for a type of medical behaviour whereby doctors might be inclined to offer both scanning and caesarean delivery. There were considerable differences between types of hospital: rates increased over the decade in the large general hospitals, but this increase was from a high baseline. Secondary-level hospitals started from a low baseline but increased their rates of caesarean section substantially towards the end of the decade, reaching the same level as the major hospitals. A similar trend was evident in other health facilities, such as small township-level family planning hospitals and private clinics.

The data were obtained from a population sample stratified by place of residence, accounting for variations in socioeconomic conditions currently prevalent in China. The findings reported directly apply to the selected counties in the survey, which give a wide geographic coverage of the country. However, the results cannot be generalized to the whole country owing to the purposive selection of the project counties. Specific health-service interventions to strengthen maternal and other reproductive health-care provisions have been initiated in these counties; it is possible that a different pattern of associations with caesarean delivery would have been observed in other areas. The survey enquired whether women had expressed a preference for caesarean delivery. This was a single item in the questionnaire that did not allow for elaboration to give the full picture of the decision-making process between doctors and patients, for which in-depth studies would be required.23 We were not able to determine whether medical indications for caesarean section were present.

The present findings are consistent with the national pattern of a steady increase in caesarean sections in China, a country where health-care services are undergoing rapid expansion and modernization. Within the limitations discussed above, our data show a huge demand for the procedure across urban and rural areas of China in the context of the overall acceptance of the “one-child norm”.24 The finding that women with only one child were more likely to undergo a caesarean section may reflect women’s perceptions regarding the efficacy of the procedure as a means to ensure newborn survival and to avert the risks of birth complications or stillbirth. Consistent with our findings, a cohort study showed that women are increasingly inclined to opt for delivery by caesarean for non-medical reasons such as fear of labour pain, concerns about date or time of birth that are traditionally believed to be auspicious and the belief that delivery by caesarean ensures protection of the baby’s brain.13

Aside from the medical benefits and risks of caesarean delivery for individual women, an important consideration is the economic impact of this new trend. Data gathered during evaluation activities in one of the study areas in 2005 indicated that the cost of caesarean delivery is approximately 2000–3000 Chinese yuan (approximately US$ 262–394) in rural areas. This includes the cost of the actual delivery, a 1-week hospital stay, food and transportation. The corresponding costs in an urban facility range from 5000 to 7000 yuan (approximately US$ 656–918) to more than 10 000 yuan (approximately US$ 1312) in major hospitals in big cities. While fees are not typically paid by mothers directly to obstetricians, in the context of a diversifying health economy in which institutions benefit from increasing activity there are performance-related incentives for staff in some hospitals, depending on the number of procedures and the revenue that physicians generate for their hospitals.25 It is worth noting here that the trends in rates of caesarean section seen in the present study corresponded very closely to those at the facilities in a selected county sample where we conducted our field evaluation. Although we cannot generalize,26 this observation to some extent provides reassurance as to the validity of survey estimates.

The associations between antenatal care, sonography and caesarean delivery may contain some element of self-selection; for example, women with high-risk pregnancies and identified problems are presumably more likely to be advised to have more consultations and investigations such as ultrasound. On the other hand, it is possible that increased use of antenatal services leads to increased medicalization of the pregnancy, including a greater openness to caesarean delivery. Overall, routine sonography in late pregnancy has not been shown to improve perinatal mortality27 and there is limited sensitivity and specificity for the detection of fetal problems such as intrauterine growth restriction. Further research to disentangle clinical factors from maternal demand is required but is problematic. Even when considering clinical factors and risk for caesarean delivery in large cohorts, such as that of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) study in England,28 it is impossible to avoid the effect of physician preference in the face of specific clinical circumstances.

The structural changes in public health systems could partially explain the increasing caesarean section rates. Between 1993 and 2002, the number of newly established general hospitals increased by about 11% (from 11 426 in 1993 to 12 716 in 2002), while the number of MCH hospitals increased by 2.1% until 1999 and thereafter showed a decline (from 3115 in 1993 to 3067 in 2002).29 Although the increase in the number of MCH hospitals was trivial, the number of new beds in the MCH systems increased by more than 70% between 1993 and 2002.29 In comparison to the family planning health systems, which are relatively better-funded, the MCH institutions (especially in rural areas) were under pressure to generate revenue from user fees and other medical prescriptions.30,31

The rise in rates of caesarean section in China presents problems of both equity and scale. Some of the increase in demand could be financed by patients, and might have taken place in new or expanded private hospitals particularly during 1990–2002, when the contribution of public funding to local public health revenues declined by almost two-fifths.25,32,33 However, current models of community-based health insurance that typically involve low premiums but high payments at the time of use have tended to benefit wealthier urban households more than poorer rural households.34 Despite a rise in private or insurance-based funding, there is an inevitable additional burden on the public health system, especially on the training and deployment of obstetricians, theatre nurses and anaesthesiologists able to meet the demand for surgery. Other infrastructure such as hospital beds, operating theatres, and laboratory and transfusion services will also be placed under strain as demand increases. Given the emergence of secondary-level hospitals as major providers of caesarean section, efforts to contain the increase based on clinical review and monitoring will need to consider case mix, i.e. the complexity of cases seen. In a British study, 34% of the variance in rates of caesarean section could be ascribed to case-mix differences.35 Service frameworks and clinical guidelines are important policy instruments for containing inappropriate medical practice, and they are now receiving attention in China.36 However, even where implemented, international experience shows that guidelines are not always observed by obstetricians: incomplete compliance with United States of America national guidelines on caesarean delivery for suspected fetal distress in labour was commonplace.37 Other avenues that might have the potential to contain the rise in caesarean delivery – such as promotion of midwifery-led maternity care models and active involvement of new mothers in the development of local health services that emphasize birth as a normal process – have so far received limited attention in China.

It is imperative that health policies and programmes aimed at improving reproductive and child health should initiate efforts to systematically monitor delivery complications and trends in caesarean section in China. Qualitative and quantitative research is needed to understand the underlying reasons, factors and decision-making aspects of Chinese women, couples and physicians related to the demand and use of caesarean section. ■

Footnotes

Funding: The results reported in this study were drawn from a cross-sectional survey conducted jointly by China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission and Ministry of Health on behalf of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) as a part of the Fifth Country Program in China. The work by Guo Sufang and Zhao Fengmin was supported by the Chinese health ministry; Guo Sufang was affiliated with the National Centre for Women and Children’s Health when this project was completed. The work by Sabu S Padmadas, James J Brown and R William Stones was supported by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Government Department for International Development through UNFPA China.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;2:436–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black C, Kaye JA, Jick H. Cesarean delivery in the United Kingdom: time trends in the general practice research database. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:151–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000160429.22836.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laws, PJ, Sullivan EA. Australia’s mothers and babies 2002. Perinatal Statistics Series No. 15. Sydney: National Perinatal Statistics Unit; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tranquilli AL, Giannubilo SR. Cesarean delivery on maternal request in Italy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84:169–70. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caesarean sections. Postnote No. 184. London: Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology; 2002. Available from: http://www.parliament.uk/post/pn184.pdf

- 6.Dobson R. Caesarean section rate in England and Wales hits 21%. BMJ. 2001;323:951. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7319.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamm BL. Cesarean section: a worldwide epidemic? Birth. 2000;27:139. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray SF. Relation between private health insurance and high rates of caesarean section in Chile: qualitative and quantitative study. BMJ. 2000;321:1501–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potter JE, Berquó E, Perpétuo IHO, Leal OF, Hopkins K, Souza MR, et al. Unwanted caesarean sections among public and private patients in Brazil: prospective study. BMJ. 2001;323:1155–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padmadas SS, Kumar S, Nair SB, Kumari A. Caesarean section delivery in Kerala, India: evidence from a National Family Health Survey. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:511–21. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belizán JM, Athabe F, Barros FC, Alexandar S. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ. 1999;319:1397–402. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7222.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai WW, Marks JS, Chen CHC, Zhuang YX, Morris L, Harris JR. Increased cesarean section rates and emerging patterns of health insurance in Shanghai, China. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:777–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei H, Wen SW, Walker M. Determinants of caesarean delivery among women hospitalized for childbirth in a remote population in China. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:937–43. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee LY, Holroyd E, Ng CY. Exploring factors influencing Chinese women’s decision to have elective caesarean surgery. Midwifery. 2001;17:314–22. doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng L, Yue Y. Analysis on the 45-year caesarean section rate and its social factors. Med Soc. 2002;15:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu WL. Cesarean delivery in Shantou, China: a retrospective analysis of 1922 women. Birth. 2000;27:86–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y, Wen A, Zhang X. Guangdong Yi Xue. 2000;21:477–8. [Analysis on the 10-year changes of rates and indications of caesarean section] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu L, Zhou B, Hua J. Shanghai Yixue Jianyan Zazhi. 1999;22:349–51. [Study on the situation of caesarean-section in Shanghai] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner M. Choosing caesarean section. Lancet. 2000;356:1677–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03169-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitagawa EM. Components of a difference between two rates. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50:1168–94. doi: 10.2307/2281213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Working Committee for Children and Women. Reduce maternal and child mortality rate and eliminate neo-natal tetanus programme 2000–03. Beijing: Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Western Poverty Reduction Project. Project appraisal document on a proposed loan of US$60 million and a proposed credit of SDR 73.8 million to the People’s Republic of China. Report No. 18982-CHA. Washington: World Bank; 1999.

- 23.Cheung FN, Mander R, Cheng L, Chen VY, Yang XQ. Caesarean decision-making: negotiations between Chinese women and health care professionals. Evidence Based Midwifery. 2006;4:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hesketh T, Li L, Zhu WX. The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1171–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents – the evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1165–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton CK, Dubourg D, De Brouwere V, Pujades M, Ronsmans C. Reliability of data on caesarean sections in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:449–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bricker L, Neilson JP. Routine ultrasound in late pregnancy (after 24 weeks gestation). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001451. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel RR, Peters TJ, Murphy DJ. Prenatal risk factors for caesarean section. Analyses of the ALSPAC cohort of 12944 women in England. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:353–67. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.China Health Statistics Summary, 2005 Beijing: Centre for Health Statistics and Information, Ministry of Health; 2005. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.cn

- 30.Kaufman J, Fang J. Privatisation of health services and the reproductive health of rural Chinese women. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10:108–16. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Yi Y. The health sector in China: policy and institutional review. The World Bank rural health study. Washington: World Bank; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Rao K, Hsiao WC. Medical spending and rural impoverishment in China. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21:216–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y. Reforming China’s urban health insurance system. Health Policy. 2002;60:133–50. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00207-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Yip W, Zhang L, Wang L, Hsiao W. Community-based health insurance in poor rural China: the distribution of net benefits. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:366–74. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paranjothy S, Frost C, Thomas J. How much variation in CS rates can be explained by case mix differences? BJOG. 2005;112:658–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong B-R, Yue J-R, Xu Y. The principles of developing evidence-based guidelines. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2006;6:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Scott JR, Scardo JA, Hendrix NW, Martin JN. Emergency cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracings: compliance with ACOG guidelines. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:975–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]