Abstract

Immune related abnormalities have repeatedly been reported in autism spectrum disorders (ASD), including evidence of immune dysregulation and autoimmune phenomena. NK cells may play an important role in neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD. Here we performed a gene expression screen and cellular functional analysis on peripheral blood obtained from 52 children with ASD and 27 typically developing control children enrolled in the case-control CHARGE study. RNA expression of NK cell receptors and effector molecules were significantly upregulated in ASD. Flow cytometric analysis of NK cells demonstrated increased production of perforin, granzyme B, and interferon gamma (IFNγ) under resting conditions in children with ASD (p<0.01). Following NK cell stimulation in the presence of K562 target cells, the cytotoxicity of NK cells was significantly reduced in ASD compared with controls (p<0.02). Furthermore, under similar stimulation conditions the presence of perforin, granzyme B, and IFNγ in NK cells from ASD children was significantly lower compared with controls (p<0.001). These findings suggest possible dysfunction of NK cells in children with ASD. Abnormalities in NK cells may represent a susceptibility factor in ASD and may predispose to the development of autoimmunity and/or adverse neuroimmune interactions during critical periods of development.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are complex neurodevelopmental disorders which are typically diagnosed within the first three years of life. ASD are characterized by significant impairments in social interaction and communicative skills, as well as restricted and stereotyped behaviors and interests (Association, 2000). ASD includes both Asperger’s syndrome and autism disorder, as well as pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) (Association, 2000). Specific diagnosis is determined by the nature and severity of delays or deficits in communication and social interactions and the presence or absence of restricted and stereotyped behaviors/interests. Males are four times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than females (Fombonne, 2005). Over the past decade, intense interest has focused on ASD, as the prevalence appears to be increasing (Fombonne, 2005). Recent estimates, including the recent CDC study, place overall prevalence of ASD at 1 per 150 children (Fombonne, 2005; Kuehn, 2007).

Despite expanding research in ASD, its etiologies remain poorly understood and the relative contribution from genetic, epigenetic, and environmental susceptibility factors remains widely debated (Ashwood et al., 2006). Twin studies indicate a strong heritability for ASD risk (Muhle et al., 2004), and whole genome scans have revealed potential ASD candidate genes on nearly every chromosome (Szatmari et al., 2007; Veenstra-VanderWeele and Cook, 2004). Several studies have demonstrated ASD associations with immune related genes, including: complement C4 null allele (Odell et al., 2005; Warren et al., 1991), HLA-DR β1, and DR13 (6–9), and immune cell development genes, such as Reelin (RELN) and MET protooncogene (MET) (Muhle et al., 2004; Skaar et al., 2005). In addition, systemic abnormalities of the immune system have been one of the most common and long-standing reported findings in ASD (Money et al., 1971; Stubbs and Crawford, 1977). Extensive neuroimmune interactions, beginning as early as embryogenesis, offer one possible explanation for the involvement of the immune response in the development of ASD and the ongoing immune alterations demonstrated in affected individuals.

Immunological findings in ASD have been reported systemically and at the cellular level, including familial associations with autoimmune and/or immune disorders such as atopy and asthma (Ashwood and Van de Water, 2004; Comi et al., 1999; Money et al., 1971). Notably, altered production of proinflammatory signaling proteins, such as cytokines, have been identified in the plasma, peripheral immune cells, brain, and CSF of individuals with ASD (Ashwood et al., 2003; Ashwood et al., 2004; Ashwood and Wakefield, 2006; Croonenberghs et al., 2002; Jyonouchi et al., 2001; Molloy et al., 2006; Singh, 1996; Vargas et al., 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2005). Despite reported increases in inflammatory mediators in plasma and CNS tissue, immune cells isolated from individuals with ASD fail to respond appropriately to mitogen stimulation, such as phytohemagglutinin (Stubbs and Crawford, 1977; Warren et al., 1986). Moreover, there is a growing literature that demonstrates the increased presence of autoantibodies, especially to CNS proteins, in children with ASD and some mothers of children with ASD (Ashwood and Van de Water, 2004; Cohly and Panja, 2005; Wills et al., 2007; Zimmerman et al., 2007). In susceptible individuals, immune dysregulation may predispose to the generation of aberrant or inappropriate immune responses such as autoimmunity and/or adverse neuroimmune interactions which during critical developmental windows may ultimately lead to changes in neurodevelopment.

Despite the broad scope of immunological findings in ASD, no consistent and specific immunological dysfunction has emerged. Recently, a mRNA expression study of peripheral blood cells of young children with ASD found increased expression of natural killer (NK) cell-associated genes (Gregg et al., 2008). This is interesting as twenty years ago, Warren et al. reported decreased NK cell function in individuals with autism (Warren et al., 1987). NK cells have been implicated in the pathology of other neurological and behavioral disorders, including Tourette syndrome (Lit et al., 2007), schizophrenia (Yovel et al., 2000), and multiple sclerosis (Jie and Sarvetnick, 2004; Johansson et al., 2006). In addition, imbalances between inhibitory and activating NK signaling have been implicated in the development of several autoimmune diseases, including diabetes mellitus (van der Slik et al., 2007), rheumatoid arthritis (Villanueva et al., 2005), systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma (Pellett et al., 2007).

The findings of a possible association between NK cell dysfunction and ASD reported by Warren et al. (Warren et al., 1987) and RNA expression profiling implicating NK cells (Gregg et al., 2008) led us to directly address whether NK cell was altered in ASD. First, using the findings described by Gregg et al.(Gregg et al., 2008), we refined the profile of NK gene expression associated with autism. Secondly, we determined that the specific changes reflected in the RNA profiles translated to altered NK activity, and cytolytic protein production at the cellular level in a separate cohort of children diagnosed with ASD. Together, these RNA expression and cellular studies indicate a role for NK cells in the dysregulated immune responses reported in ASD.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Participants in the study were recruited in conjunction with the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risk from Genetics and Environment) study conducted at the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute; Sacramento, CA. A full description of the study and the assessment criterion has been described (Hertz-Picciotto et al., 2006). This study was approved by the UC Davis institutional review board and complied with all requirements regarding human subjects. Informed consents were obtained from legal guardians of each participant.

All children, including those from the general population, were screened for autism traits using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) (Eaves et al., 2006). Children with a preliminary outside diagnosis of autism, as well as those scoring above the screening threshold on the SCQ were further tested to confirm diagnosis and completed the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al., 1997) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Gotham et al., 2007) conducted at the M.I.N.D. institute. The ADI-R is a comprehensive clinical interview administered to parents or caregivers assessing language and communication, reciprocal social interaction, and repetitive, restricted, stereotyped behaviors or interests. Results from the interview are interpreted by using a diagnostic algorithm that correlates with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) definitions of autism. The ADOS is an observational assessment of the children suspected of having autism in various structured and unstructured situations that provide a standardized set of conditions to observe behavior in the areas of communication, play, and other areas relevant to autism. Only children who scored above the cut-off for the ADOS modules 1 and 2 for ASD and met the criteria for autism in the ADI-R were included in the study as part of the ASD study group. To reduce confounding factors, children who were ill at the time of the study, or had a temperature above 98.9°F, or were prescribed anti-psychotics were excluded from the study. None of the children had any other known medical disorder or primary diagnosis (e.g. Fragile X or Rett syndrome).

Two separate cohorts totaling 79 children between 2 and 5 years of age participated in the study. Children were selected at random from the larger CHARGE study pool, which were matched for age, gender, and postal code (Hertz-Picciotto et al., 2006). Peripheral blood from 46 children was used for RNA analysis and included 35 children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and 11 age and gender matched typically developing general population non-sibling controls (GP). All of the ASD subjects met criteria for full autism, based on ADOS and ADI-R criteria. Eighteen of the ASD subjects met the requirements for regression based on questions 11 and 25 on the ADI-R assessment. An additional 33 children (17 ASD and 16 GP) from the CHARGE study were included in the NK cellular study. Of the 17 ASD children, 16 met criteria for full autism disorder; the remaining child was reclassified as having an ASD but not full autism after the start of the study following clinician review. Three ASD subjects in the cellular analysis group met the requirements for regression based on ADI-R measures. All subjects are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and typically developing general population (GP) study populations.

| Microarray Analysis | Cellular Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | GP | ASD | GP | |

| n | 35 | 11 | 17 | 16 |

| % Males | 86% | 82% | 82% | 81% |

| Average Age | 3.6 years | 3.5 years | 3.9 years | 3.3 years |

| Age Range | 2.3–5.6 years | 2.7–4.3 years | 2.2–5.0 years | 2.3–4.8 years |

Gene Expression Studies

RNA isolation and microarray processing

RNA isolation and microarray processing were performed as described in Gregg et al (Gregg et al., 2008). Briefly, 15 ml blood was collected into 6 PAXgene vacutainer tubes (Qiagen; Valencia, CA). RNA quality was confirmed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Gene expression was assessed on the human U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA), consisting of over 54,000 oligonucleotide transcript probe sequences. Protocols from the Affymetrix Expression Analysis Technical Manual were used for labeling the RNA, hybridization to the chip, and scanning the array. Expression of select probes was validated by RT-PCR (Gregg et al., 2008). GENESPRING 7.2 software (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) was used for gene expression analysis. Background and data normalization were performed using GC-RMA followed by three-step normalization (data transformation, per chip normalization, and per gene normalization). The microarray data is available at the Gene Expression Ombudsmen (GEO) with the tracking series number GSE6575.

Principal Components Analysis

Initial findings identified in Gregg et al. (Gregg et al., 2008) suggested increased expression of a group of NK cell related genes in many of the children with ASD compared with typically developing GP children. To further investigate these findings, we performed a principal components analysis using the seven genes validated by RT-PCR (Table 2) to determine how much of the variation between groups was accounted for by these seven genes.

Table 2.

Genes used as input to Principal Components Analysis. Differential gene expression in autism spectrum disorder (n=35) compared with typically developing children (n=11) (modified from Gregg et al., 2008).

| Affymetrix GeneChip | TaqMan |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Fold Change | Fold Change | P value |

| PAM | 1.86 | 1.51 | 0.007 |

| SPON2 | 1.87 | 1.86 | 0.005 |

| IL2RB | 1.56 | 1.35 | 0.046 |

| PRF1 | 1.79 | 1.53 | 0.027 |

| GZMB | 2.01 | 1.72 | 0.014 |

| CX3CR1 | 1.60 | 1.37 | 0.006 |

| SH2D1B/EAT2 | 2.19 | 1.78 | 0.077 |

Expanded gene expression profile

Using results from the Principal Components Analysis, we conducted an unpaired t-test (fold change ≥ |1.5|, p ≤ 0.05, false discovery rate (FDR) q ≤ 0.05) comparing gene expression in children with ASD having high expression of NK cell related genes with gene expression in children having low expression of NK cell related genes.

Functional annotation

Using the expanded gene expression profile, the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://niaid.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/), supplemented by a literature search, was used to assess pathway and functional integration for genes within the expanded gene expression profile. Each annotation cluster represents a group of annotation terms with similar biological meaning due to sharing similar gene members. Enrichment Scores are the geometric mean (in -log scale) of functional annotation p-values in the corresponding functional annotation cluster; higher enrichment scores indicate overall smaller p values within a cluster. For each annotation term, p values are Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE) scores, a modified Fisher Exact Test which uses a Gaussian hypergeometric probability distribution using sampling without replacement to identify likelihood of observing identified genes by random chance (Hosack et al., 2003). False Discovery Rates (FDR) using a Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison correction are provided to adjust for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Webgestalt (http://bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt) Gene Set Analysis Toolkit was used to further examine gene expression patterns.

Cellular Studies

NK Cell Isolation

Approximately 8–10 ml peripheral blood was collected in acid-citrate-dextrose Vacutainers (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Precise volume of blood collected was determined followed by centrifugation at 2300 rpm for 10 min. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated using Histopaque (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) density gradient centrifugation at 1700 rpm for 30 min. CD56+ NK cells were positively selected by magnetic bead separation following the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec; Auburn, CA). CD56+ cells were adjusted to 3 × 106 cells/ml in RMPI media (Sigma) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Omega Biosciences Tarzana, CA). Purity of CD56+ lymphocytes for all samples exceeded 95% as assessed by flow cytometry.

NK cytotoxicity Assay

MHC-devoid K562 cells (ATCC; Manassas, VA) were used as targets to assess NK cell cytotoxicity. Sorted CD56+ PBMC were incubated for 20 hours at 37°C in round bottom 96-well culture plates with 100,000 calcein-AM labeled K562 target cells at 25:1, and 10:1 effector:target cell ratios, and 50:1 and 1:1 effector:target cell ratios when sufficient cell numbers were obtained. Cells were washed and stained with Texas-Red conjugated ethidium-homodimer-1 (Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR) and CD56-PE Cy-7 for 15 min. Cells were then washed and immediately analyzed on a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Positive and negative controls were included in every assay and run concurrently. Singly stained cells for each fluorophore used were run for compensation correction. Unstained negative controls included unlabeled K562 cells (with and without CD56+ cells) and unlabeled CD56+ cells. Positive controls for maximum lysis included calcein-AM labeled K562 cells fixed and permeablized at the end of the incubation period, prior to staining. Controls for spontaneous lysis were calcein-AM cells not incubated with any target cells. Dead K562 cells were gated on as dual-positive for calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer and were easily distinguishable from effector cells labeled with CD56 and live K562 cells.

Flow Cytometry

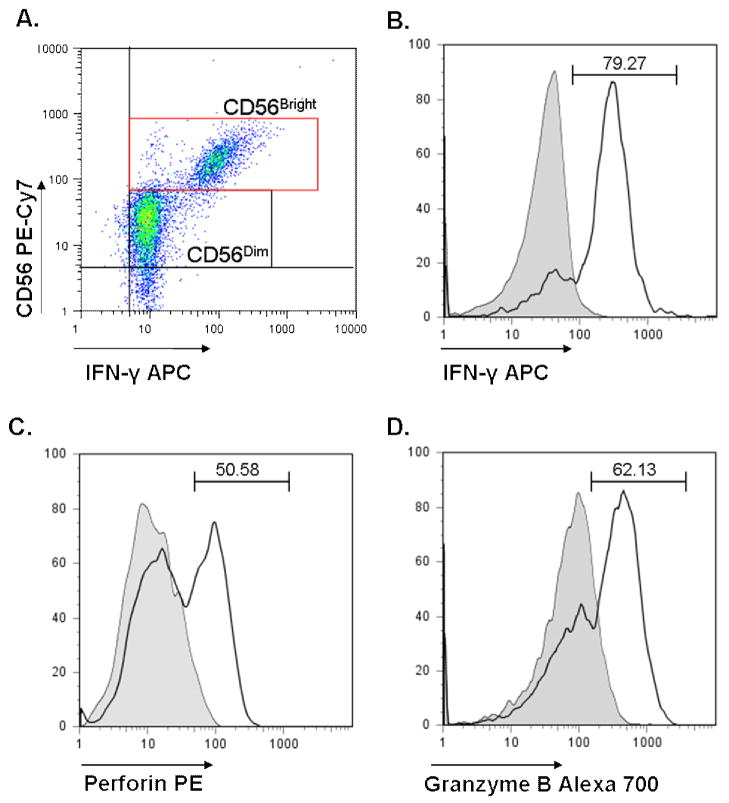

All cells were analyzed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Variance was assessed prior to start of every assay. Additionally, compensation was calculated for each assay using FACS Diva Software (BD Biosciences). Singly stained K562 and CD56+ cells were used to calculated compensation for the cytotoxicity assay, and anti-mouse antibody coated compensation beads (BD Biosciences) were used for the NK stimulation assay. A minimum of 30,000 ungated events was counted for each tube. Cell gating was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc; Ashland, OR). NK cells were discriminated from NKT cells by gating positive on CD56+ cells and negative for both CD3 and CD8. CD56+ NK cells were further divided into CD56Dim and CD56Bright NK cells based on intensity of CD56 staining. CD56Dim NK cells are associated with high natural cytotoxicity, KIR surface expression, and low cytokine production (43). Singly stained compensation controls and isotype mAb controls (BD Biosciences) were run for each subject. Positive gating was determined by setting gates at isotype control maximums for each subject’s cells. Additionally, cells were stained with CD3, CD8, and CD56 with isotype controls in place of PE and APC to appropriately set positive gates for perforin and IFNγ. NK cells have previously been separated into two categories: CD56Dim cells, which are the principal producers of cytolytic proteins, and CD56Bright cells, which are the principal cytokine producers (41). As such, CD56Dim, and CD56Bright NK cells were assessed separately in order to determine if there were differences in perforin, granzyme B and IFNγ in ASD versus GP groups. Subset determination and examples of staining are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CD56Dim and CD56Bright subset determination.

A representative dot plot showing markers for CD56+ NK cell subsets (A). Following selection of CD3− CD8− cells, CD56Dim and CD56Bright cells can be identified by density of CD56 staining. A representative example of an ASD subject is shown for determination of frequency of IFNγ positive CD56Bright cells (B) and frequency of CD56Dim cells positive for perforin (C) and granzyme B (D). The shaded line denotes isotype control. The percentage of positive cells is denoted above each histogram.

Antibodies

For the analysis of cell surface markers we used the following mouse-anti-human antibodies: PerP-Cy5.5 labeled CD3, PE-Cy5 labeled CD8, and PE-Cy7 labeled CD56 (BD Biosciences). For intracellular molecule analysis (see below), we used PE labeled perforin, APC labeled IFNγ, and Alexa-700 labeled granzyme B (BD Bioscicences).

NK Cell Stimulation

CD56+ PBMC were stimulated as above with unlabeled K562 cells at 25:1 and 10:1 effector:target cell ratios. Additional CD56+ PBMC were incubated alone as unstimulated controls. Brefeldin-A was added at a final concentration of 10μg/ml at the incubation start to trap newly synthesized proteins including cytokines (Sigma). 6 μg/ml monensin was additionally added to prevent degradation of endocytic vesicles (Sigma). Cells were labeled with cell surface antibodies for 20 minutes at room temperature in PBS containing 0.5% BSA to block non-specific binding. Cells were washed and fixed at 4°C for 10 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde containing saponin. Cells were washed with PBS containing saponin detergent and stained with intracellular antibodies for 30 minutes. Cells were washed again, resuspended in buffer containing saponin and analyzed by flow cytometry within 2 hours of collection. Singly stained compensation beads (BD Biosciences) were used to calculate compensation. Unlabeled cells were used as an additional control.

Statistics

Unpaired t-tests were used to examine the flow cytometry and cytotoxicity data (p<0.05 considered significant). The calculations were conducted utilizing GraphPad Prism 5 Software (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA).

Results

Gene Expression Study

Refined gene expression profile

Previously, we demonstrated that seven genes were expressed at higher levels in children with ASD compared with matched controls, using microarrays and validation by RT-PCR (Gregg et al., 2008). To further examine the differences in gene expression in ASD, we used these seven genes as input for a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and compared gene expression profiles in 35 children with ASD with 11 typically developing general population control (GP) children (Table 2). There were significantly more children with ASD who had a high expression of these genes compared with GP controls (Chi-square=11.9, p=0.0005). Unpaired t-tests used to compare ASD subjects with high expression of these seven PCA genes with those GP that had low expression, revealed that a total of 626 probes showed differential expression between these groups. Of these 626 probes, expression of 82 were significantly higher and 544 were significantly lower in the ASD group that had increased expression of the seven PCA genes. Of interest, several of the upregulated transcripts were related to NK function (Table 3), whereas many of the probes with lower expression were related to cellular proliferation (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Increased expression of NK cell related genes in peripheral blood from children with autism spectrum disorder compared with typically developing controls using microarray analysis.

| Fold-change | Gene Name | Protein Name |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2 | CCL4 | MIP-1 Beta |

| 1.7 | CCL5 | RANTES |

| 1.7 | CD160 | CD160 |

| 2.4 | CTSW | Cathepsin W/Lymphopain |

| 1.8 | CX3CR1 | Chemokine (CX3C motif) receptor 1 |

| 2.7 | GZMB | Granzyme B |

| 2.4 | GZMH | Granzyme H |

| 1.5 | GZMM | Granzyme M |

| 1.9 | IL2RB | Interleukin 2 receptor beta |

| 2.1 | ITGB2 | CD18/Beta 2 integrin |

| 1.5 | KIR2DL1 | KIR, two domains, long cytoplasmic tail |

| 1.7 | KIR2DL2 | |

| 1.5 | KIR2DL3 | |

| 1.6 | KIR2DL5A | |

| 2.2 | KIR2DS2 | KIR, two domains, short cytoplasmic tail |

| 1.7 | KIR2DS5 | |

| 1.7 | KIR3DL1 | KIR, three domains, long cytoplasmic tail |

| 1.7 | KIR3DL2 | |

| 1.7 | KIR3DL3 | |

| 1.8 | KLRD1 | CD94 |

| 1.7 | KLRF1 | ITIM2 |

| 2.5 | KSP37 | KSP37 protein |

| 1.5 | NFATC2 | Nuclear factor of activated T cells |

| 2.5 | NKG7 | Natural killer cell group 7, sequence |

| 1.9 | PDGFD | Platelet derived growth factor D |

| 2.6 | PRF1 | Perforin 1 |

| 2.2 | PTGDR | prostaglandin D2 receptor |

| 2.0 | TBX21 | T-box 21/TBET |

| 2.0 | TGFBR3 | Transforming growth factor β receptor III |

| 1.6 | TRGC2 | T cell receptor gamma constant 2 |

Table 4.

The top two annotation clusters identified by DAVID for up regulated probes in ASD. Count defines the number of genes occurring within specified group. False discovery rate (FDR) denotes the number of genes expected to occur within a group by chance.

| Enrichment Score: 5.96 | Count | p Value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defense response | 22 | 1.20E-12 | 4.10E-09 |

| Immune response | 21 | 1.50E-12 | 2.50E-09 |

| Response to biotic stimulus | 22 | 3.00E-12 | 3.30E-09 |

| Cellular signaling | 28 | 8.20E-09 | 5.40E-06 |

| Disulfide bond formation | 27 | 9.10E-09 | 3.60E-05 |

| Signal peptide | 28 | 2.00E-07 | 4.00E-04 |

| Response to pest, pathogen or parasite | 13 | 4.90E-07 | 4.10E-04 |

| Response to other organism | 13 | 8.40E-07 | 5.70E-04 |

|

| |||

| Enrichment Score: 5.74 | Count | p Value | FDR |

|

| |||

| Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 13 | 9.70E-13 | 2.10E-10 |

| Antigen processing and presentation | 9 | 5.40E-09 | 5.80E-07 |

| Immunoglobulin subtype | 13 | 2.90E-08 | 1.50E-04 |

| Immunoglobulin-like | 13 | 1.10E-07 | 2.70E-04 |

| MHC class I receptor activity | 6 | 2.00E-07 | 1.60E-04 |

Functional annotation

The 82 upregulated probes in ASD corresponded to 59 known genes, the majority of which have been ascribed to leukocyte function, more specifically NK cell cytotoxic function (Table 3). Thirty of the 59 genes (42 of the 82 probes) were associated with leukocytes, and 22 of these 59 (37%) were associated with cytolytic cells, predominantly NK cells. There was increased expression for 11 probes for killer cell immunoglobulin receptors (KIR), and 9 of these were probes for inhibitory KIR (long cytoplasmic domains). Additionally, expression of CD94 (2 probes) and CD160 (1 probe), which are both involved in MHC-I recognition and cytolytic activity increased (Barakonyi et al., 2004; Terrazzano et al., 2002). The expression of KSP37, a gene restricted to NK cells and co-expressed with perforin during viral infection (Ogawa et al., 2001), increased 2.5-fold. Similarly, the RNA levels for perforin (2 probes), a pore forming protein secreted by activated NK cells, also increased 2.5 fold. The expression of three probes specific for granzymes, which enter the pore formed by perforin to induce apoptosis, were also increased. Thus, a profile indicating paradoxically increased expression of both inhibitory (KIR long cytoplasmic domain) and cytolytic (CD94, CD160, granzymes, perforin) natural killer cell-related genes were identified. Using the up-regulated genes as inputs, functional annotation clusters from the DAVID database strongly supported these findings showing that pathways and functions associated with NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity and antigen presentation were altered in ASD (Table 4). Furthermore, functional annotation clusters using the down-regulated genes (544 probes) as inputs indicated that ribosomal processing, cellular biosynthesis, intracellular organelles, cellular metabolism and cellular proliferation were altered in ASD (Table 5).

Table 5.

The top two annotation clusters identified by DAVID for down regulated probes in ASD. Count defines the number of genes occurring within specified group. False discovery rate (FDR) denotes the number of genes expected to occur within a group by chance.

| Enrichment Score: 7.49 | Count | p Value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosome | 31 | 2.00E-13 | 6.40E-11 |

| Structural constituent of ribosome | 31 | 4.90E-13 | 1.20E-09 |

| Ribonucleoprotein complex | 40 | 1.00E-12 | 2.10E-10 |

| Protein biosynthesis | 44 | 2.80E-10 | 4.80E-07 |

| Macromolecule biosynthesis | 47 | 4.00E-10 | 4.60E-07 |

| Biosynthesis | 62 | 2.70E-08 | 2.30E-05 |

| Cellular biosynthesis | 57 | 4.40E-08 | 3.00E-05 |

| Large ribosomal subunit | 11 | 1.70E-07 | 1.50E-05 |

| Ribonucleoprotein | 22 | 3.00E-07 | 4.00E-04 |

| Ribosomal protein | 20 | 3.10E-07 | 2.00E-04 |

| Protein complex | 76 | 1.40E-05 | 9.00E-04 |

|

| |||

| Enrichment Score: 6.85 | Count | p Value | FDR |

|

| |||

| Intracellular processing | 250 | 2.10E-15 | 1.30E-12 |

| Cellular physiological process | 278 | 3.30E-12 | 1.10E-08 |

| Intracellular organelle | 215 | 5.30E-12 | 8.30E-10 |

| Cellular metabolism | 211 | 1.00E-07 | 5.90E-05 |

| Intracellular membrane-bound organelle | 179 | 3.90E-07 | 3.00E-05 |

| Membrane-bound organelle | 179 | 4.00E-07 | 2.80E-05 |

| Metabolism | 219 | 6.90E-07 | 3.30E-04 |

| Physiological process | 286 | 8.20E-07 | 3.50E-04 |

Cellular Analyses

Altered NK cell frequency in ASD

To further expand upon these initial gene expression studies, we performed a series of functional and cellular analyses on isolated NK cells in ASD compared with matched control children. First we assessed the frequency of NK cells in peripheral blood in ASD. After cell isolation there were significantly more CD56+ NK cells, per ml blood drawn, from children with ASD (21.24 ± 3.40 × 104 CD56 cells/ml blood, mean ± SEM, p<0.05) as compared with typically developing GP children (14.45 ± 1.98 × 104 CD56 cells/ml).

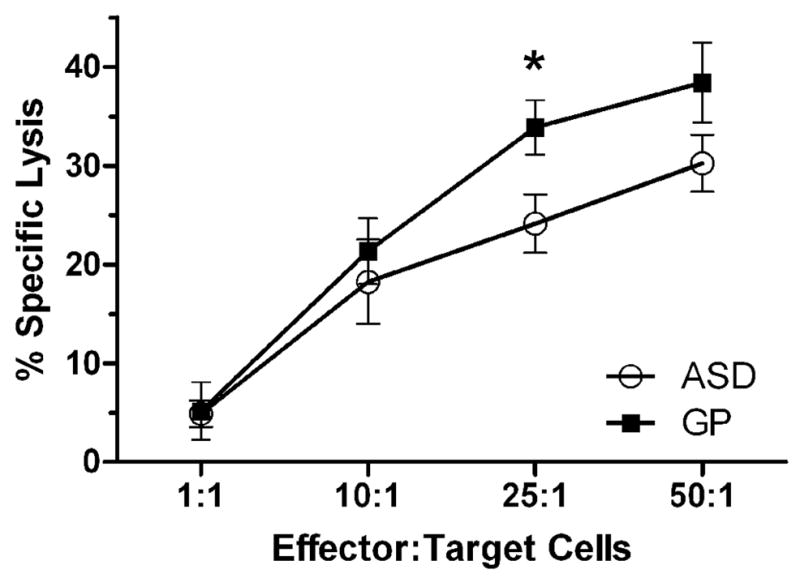

Decreased NK cytotoxicity in ASD

We used MHC-devoid K562 cells as a target cell line to determine the ability of NK cells to recognize and lyse a target cell. NK-mediated cytotoxicity was significantly decreased in children with ASD compared with GP controls at a NK:K562 ratio of 25:1 (p=0.02, Figure 2, values corrected for spontaneous K562 cell lysis).

Figure 2. NK target cell lysis reduced in autism.

Mean percent specific K562 lysis is shown for the indicated ratios of NK effector to K562 target cells. Bars represent standard error of the mean. A reduction in cytotoxic activity of cells obtained from ASD subjects was observed at cellular ratios above 1:1, which was significant at the 25:1 NK:K562 ratio (p = 0.02).

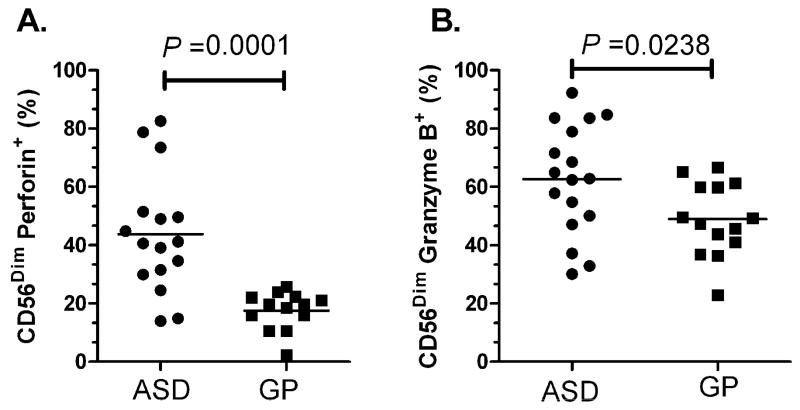

Increased cytotoxic capacity in ASD

To determine the frequency of NK CD56Dim and CD56Bright cells that express cytolytic effector molecules in un-stimulated conditions, we assessed whether NK cells contained increased intracellular stores of the cytolytic granules, perforin and granzyme B. There were no differences in the ratio of CD56Dim/Bright cells in ASD compared with GP controls (data not shown). The frequencies of CD56Dim, and CD56Bright NK cells subsets that stained positive for the functional proteins perforin, granzyme B and IFNγ are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Frequency of CD56Dim and CD56Bright NK cell subsets that stain positively for perforin, granzyme B and IFNγ before and after stimulation. Frequency of cells ± standard error of mean (SEM) shown for each measure.

| Assay | ASD | GP | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstimulated, Perforin: | |||

| CD56Dim | 43.8 ± 5.1 % | 24.5 ± 7.1 % | 0.0001 |

| CD56Bright | 14.9 ± 2.3 % | 11.3 ± 2.3 % | NS |

| Stimulated, Perforin: | |||

| CD56Dim, 10:1 NK:K562 | 13.7 ± 2.5 % | 47.0 ± 5.2 % | 0.0001 |

| CD56Dim, 25:1 NK:K562 | 16.9 ± 3.4 % | 53.4 ± 4.6 % | 0.0001 |

| CD56Bright, 10:1 NK:K562 | 14.3 ± 2.0 % | 26.7 ± 1.7 % | 0.002 |

| CD56Bright, 25:1 NK:K562 | 12.6 ± 1.7 % | 23.8 ± 3.6 % | 0.005 |

|

| |||

| Unstimulated, Granzyme B: | |||

| CD56Dim | 62.6 ± 4.9 % | 47.5 ± 4.0 % | 0.02 |

| CD56Bright | 19.6 ± 1.8 % | 17.1 ± 2.2 % | NS |

| Stimulated, Granzyme B: | |||

| CD56Dim, 10:1 NK:K562 | 43.5 ± 2.4 % | 67.6 ± 4.0 % | 0.0001 |

| CD56Dim, 25:1 NK:K562 | 47.4 ± 4.7 % | 74.6 ± 3.4 % | 0.0001 |

| CD56Bright, 10:1 NK:K562 | 40.6 ± 5.4 % | 68.8 ± 4.1 % | 0.0004 |

| CD56Bright, 25:1 NK:K562 | 36.5 ± 3.9 % | 71.7 ± 3.0 % | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Unstimulated, IFNγ: | |||

| CD56Dim | 39.1 ± 5.7 % | 19.1 ± 3.9 % | 0.003 |

| CD56Bright | 72.1 ± 6.1 % | 53.4 ± 6.1 % | 0.04 |

| Stimulated, IFNγ: | |||

| CD56Dim, 0:1 NK:K562 | 21.2 ± 3.4 % | 43.2 ± 4.1 % | 0.0004 |

| CD56Dim, 25:1 NK:K562 | 30.6 ± 8.2 % | 46.6 ± 4.4 % | NS |

| CD56Bright, 10:1 NK:K562 | 52.1 ± 5.6 % | 82.1 ± 4.8 % | 0.0006 |

| CD56Bright, 25:1 NK:K562 | 56.4 ± 7.9 % | 85.9 ± 5.0 % | 0.009 |

Under un-stimulated conditions, there was a significant increased frequency of CD56Dim NK cells that had positive staining for perforin in the ASD group (43.78 ± 5.12%, mean ± SEM) compared with GP controls (24.52 ± 7.12%, p=0.0001) (Figure 3A). Similarly, there was a significant increase in the frequency of CD56Dim NK cells that had positive staining for Granzyme B in the ASD group (62.59 ± 4.88%) compared with GP controls (47.52 ± 4.00%, p=0.02, Figure 3B). These data are consistent with our genomic findings that showed a greater than two-fold increased RNA gene expression of perforin and granzyme B in ASD children compared with GP controls. We also assessed the frequency of CD56Bright cells that had positive staining for perforin and granzyme B to determine if differences in the frequencies in CD56Bright cells contributed to our findings. There were no statistically significant differences between the frequencies of CD56Bright NK cells that were stained positive for perforin and granzyme B between the ASD and control groups (Table 6).

Figure 3. Increased resting cytolytic capacity in NK cells from ASD subjects.

Under unstimulated conditions, a significantly higher frequency of CD56Dim NK cells from children with ASD stained positive for cytolytic proteins A) perforin and B) granzyme B when compared with GP controls. Mean frequencies are shown.

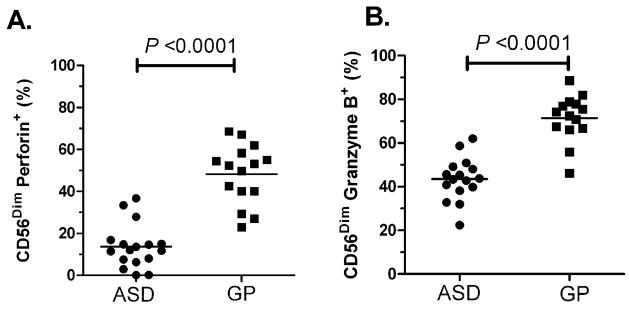

Cytolytic activity of stimulated NK cells

NK cells were cultured with MHC-devoid target cells at 10:1 and 25:1 effector:target cell ratios to activate the NK cells. The frequencies of perforin and granzyme B containing NK cells following stimulation was assessed by flow cytometry (Table 6). Following stimulation, there were significantly reduced frequencies of CD56Dim and CD56Bright NK cells that stained positive for the cytolytic proteins perforin and granzyme B in children with ASD (p<0.005). In contrast, in the GP control children, following stimulation with target cells there were an increased frequencies of CD56Dim and CD56Bright NK cells that stained positive for perforin and granzyme B (p<0.006). As a result the frequencies of CD56Dim cells that stained positive for perforin, following stimulation at the 10:1 NK:K562 cells ratio, were significantly decreased in ASD (13.72 ± 2.54%) compared with GP controls (47.01 ± 5.16%, p<0.0001, Figure 4). It is interesting to note that there was very little overlap between ASD and GP controls for the frequency of CD56Dim cells staining positive for perforin (Figure 4A, 10:1 stimulation shown). Similarly, the frequencies of CD56Dim cells that stained positive for granzyme B, were significantly lower in ASD (43.51 ± 2.44%) compared with GP controls (67.60 ± 3.96%, p<0.0001, Figure 4B), following stimulation at the 10:1 NK:K562 cells ratio. Results for the CD56Bright NK cell subset followed a similar trend, indicating that the difference following stimulation was not restricted to the CD56Dim NK population (Table 6).

Figure 4. Reduced response to stimulation in NK cells from ASD subjects.

Following stimulation with MHC-I deficient target cells at a 10:1 NK:K562 cell ratio, a significantly lower frequency of CD56Dim NK cells stained positive for cytolytic proteins A) perforin and B) granzyme B in children with ASD compared with GP controls. Mean frequencies are shown.

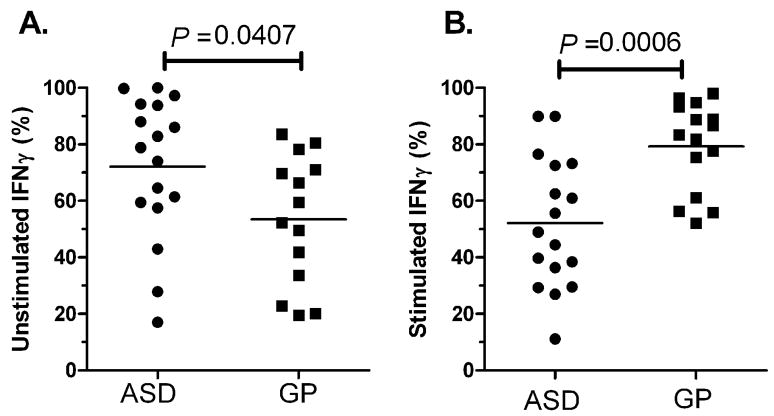

NK cells producing IFNγ in ASD

We sought to determine the frequency of NK cells producing the immune-stimulatory cytokine, IFNγ. Previous reports have demonstrated that CD56Bright NK cells are the principal cytokine producing NK cell subset (Cooper et al., 2001), and we found similar trends between NK subsets in both ASD and GP controls (Table 6). Under resting conditions, the frequency of IFNγ positive cells were increased in the CD56Bright subset in children with ASD (72.10 ± 6.11%, mean ± SEM) compared with GP controls (53.43 ± 6.10%, p=0.04; Figure 5A, Table 6). This trend was also present in the CD56Dim NK cell population with significantly higher frequencies of the CD56Dim NK cells staining positive for IFNγ in ASD (39.14 ± 5.73%) compared with GP control (19.11 ± 3.90%, p=0.003, Table 6). Following stimulation with K562 target cells, IFNγ staining in NK cells was increased in GP controls but not in ASD. Thus, within the CD56Bright cell population, there were nearly 20% fewer NK cells staining positive for IFNγ in ASD children following stimulation, compared with an increase of similar magnitude (29%) in NK cells staining positive for IFNγ in GP controls after stimulation. Moreover, following stimulation at the effector:target ratio of 10:1 NK:K562 cells, the frequency of CD56Bright cells staining positive for IFNγ was decreased in ASD (52.13 ± 5.60%) compared with GP controls (82.02 ± 4.77%, p=0.0006, Figure 5B). The finding of reduced IFNγ production is consistent with the lower frequencies of NK cells staining for perforin and granzyme B proteins after stimulation that is observed in ASD. Collectively, the data suggest that following stimulation there is a down-regulation of already chronically activated NK cells in ASD.

Figure 5. Frequency of IFNγ positive NK cells is altered in ASD.

Frequencies of CD56Bright NK cells which stain positively for IFNγ in ASD and GP children are shown for A) unstimulated and B) stimulated with 10:1 NK:K562 cells. In the absence of stimulation, the frequency of NK cells with positive staining for IFNγ was increased in children with ASD compared with GP controls. However, following stimulation decreased frequencies of IFNγ-positive NK cells were observed in the ASD group. Mean frequencies are shown.

Discussion

Findings from our current study demonstrate that there are clear and significant abnormalities in the gene expression, frequency and function of NK cells obtained from 2–5 year old children with ASD compared with GP controls. Previously, Gregg et al., examined gene expression changes in children with autism who were distinguished based on the pattern of onset of their disorder (i.e. early onset autism versus late onset/regressive autism) and compared these findings with typically developing controls (Gregg et al., 2008). Using microarray analysis, these studies revealed that 12 gene probes, representing 11 different genes, were differentially expressed in early onset and regressive types of autism compared with the controls. Seven of these genes, which were known to be expressed in NK cells and involved in NK cell-mediated pathways, were confirmed by RT-PCR. Transcriptomics does not always predict protein differences or functional deficiencies. Moreover, although the genes that were shown to be differentially expressed are predominantly associated with NK cells they can also be present in subsets of CD8+ T cells, some populations of CD4+ T cells including NKT cells, and in subsets of dendritic cells. The transcriptional data identified in Gregg et al. (2008), demonstrated changes in blood mRNA expression but did not investigate protein levels in the NK cell population nor did it report any functional readouts from the NK cell population. In the current study we sought to identify and elucidate differences in the physiological responses of NK cells in autism and to further refine the transcriptional analysis with an emphasis on NK cell related genes and pathways. Direct cellular protein analyses on a single NK cell basis, as well as dynamic cellular functions following activation were performed. To further refine the gene expression analysis, a principal component analysis inputing the 7 genes previously identified as different in autism was performed. The present study adds new and important information which demonstrates that protein levels and functional responses are altered in NK cells in children with autism, and adds to the previous report showing NK cell related gene expression changes in autism. We demonstrate that there are: 1) increased levels of cytolytic proteins in resting NK cells; 2) altered NK response to stimulation; and 3) changes in gene expression consistent with altered cellular activation in ASD compared with controls. Similar gene changes to those reported here are also seen in gene expression profiling of isolated NK cells stimulated with IL-2 (Dybkaer et al., 2007), which suggests that circulating NK cells in ASD are persistently activated rather than quiescent.

Analysis of cell function on a single cell basis supports the gene expression findings. Under resting conditions, we observed increased frequencies of NK cells that were positive for the cytotoxic granule proteins, perforin, and granzyme B, and for the cytokine IFNγ in blood from children with ASD. Both CD56Dim cytotoxic granule production of perforin and granzyme B, and CD56Bright NK cells production of IFNγ were increased and suggested that abnormalities in NK cell function were not confined to one specific NK cell subset. Moreover, abnormalities in NK function were observed following stimulation, with ASD subjects demonstrating reduced NK cell mediated-target cell cytotoxicity, reduced frequencies of NK cells staining for cytolytic proteins, and reduced frequencies of NK cells staining for cytokine production compared with controls. One possible explanation for these findings is that the NK cells from the ASD group have attained their maximum activation potential in vivo and are not able to respond to further stimulation in vitro. This could explain why even though there was a high resting cytotoxic capacity (i.e. increased gene expression and protein levels of perforin and granzyme B) there was decreased lysis of K562 cells in the ASD group when they were assessed in vitro. It is interesting to note that in some autoimmune diseases, including those which affect neurological functions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), circulating lymphocytes are activated in the periphery and fail to respond to further mitogen stimulation in vitro (Gershwin et al., 1979; Vervliet and Schandene, 1985). Several previous studies support the potential role of autoimmune processes in autism, including increased familial histories of immune and autoimmune disorders (Ashwood and Van de Water, 2004; Croen et al., 2005; Mouridsen et al., 2007; Sweeten et al., 2003), as well as the frequent finding of brain-reactive autoantibodies in ASD (Cabanlit et al., 2007; Connolly et al., 2006; Connolly et al., 1999; Silva et al., 2004; Singh and Rivas, 2004; Singh et al., 1997; Todd et al., 1988; Wills et al., 2007; Zimmerman et al., 2007). Recently, two laboratories, one that used maternal samples obtained from the same CHARGE study population as utilized here (Braunschweig et al., 2008) and the second from a separate geographically distinct population based study (Early Markers in Autism)(Croen et al., 2008) both reported the presence of autoantibodies that were reactive to fetal brain proteins in plasma specimens from mothers with children with autism but not mothers with typically developing children or children with developmental delays. These data suggest that possible maternal immune responses could affect fetal brain development and may be involved in a significant number of cases of autism. The exact nature of the function of these putative autoantibodies, what they recognize and whether they influence immune development in the child still remains to be resolved.

Despite repeated confirmed associations with autoimmune disease, the contribution of NK cells in these conditions is unclear. NK cells may be protective in autoimmune processes by inhibiting or killing autoreactive T cells or by affecting self-antigen presentation by antigen presenting cells (Segal, 2007). In MS for example, NK cells may be closely involved with remission of disease with mRNA expression of IL-5 and IL-2R by NK cells (Takahashi et al., 2001). Cytotoxic activity can also directly correlate with MS disease activity (Infante-Duarte et al., 2005; Kastrukoff et al., 1998),. In addition, highly cytolytic CX3CR1-positive NK cells are reported in active MS disease (Infante-Duarte et al., 2005). Loss of CX3CR1 selectively decreased NK cell migration into the CNS and was associated with increased neurological symptoms and mortality in a murine EAE model of MS (37). The role of NK cells in CNS diseases and neurodevelopmental disorders are likely complex. However, it is possible that NK cells may be critical in regulating neuronal inflammation and that defects in NK cell activity could permit alterations in normal neuroimmune regulation and function.

As NK cells play an important role in the host defense against infections, it is possible that abnormal or altered NK cell-mediated responses may modify susceptibility to infections. Consistent with an infection risk factor are reports of cellular and humoral immune dysfunction in ASD, as well as associations with more restricted HLA phenotypes including HLA-DR4 [4]. Moreover, medical chart reviews have demonstrated that there is an increased risk of ear and genitourinary tract infections in infants and young children with ASD (Niehus and Lord, 2006; Rosen et al., 2007). This evidence suggests that a potential environmental factor that may lead to changes in early brain development is perinatal infection. Recently, Rastogi et al. reported humoral immune responses generated in fetuses following maternal influenza vaccination as early as 29 weeks gestation (Rastogi et al., 2007). This finding demonstrates that antigen can cross the placenta, be recognized, and elicit a competent response by the fetal immune system. A defect residing in immune cells of the fetus could explain the increased risk of infection observed in the first month of life in some children with ASD (Rosen et al., 2007). As fetal NK cells are one of the predominant immune cells early in fetal life (Thilaganathan et al., 1993), abnormalities in these cells may have a major effects on early neurodevelopment. TNFα and IFNγ, which are both produced by NK cells, can damage cells of the CNS (Czlonkowska et al., 2005; Lambertsen et al., 2004) and can disrupt neurodevelopment (Gilmore et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2003). In addition, the neuropoietic cytokine IL-6, also produced by NK cells, can have direct effects on neurons and glia, including changes in proliferation, survival, neurite outgrowth, and gene expression (Gadient and Patterson, 1999; Mehler and Kessler, 1998). However, reports that associate ASD with infectious agents only account for a small proportion of ASD cases and they have implicated more than one potentially causative pathogen (Chess, 1971; Deykin and MacMahon, 1979; Stubbs et al., 1984). As such, rather than a single specific causative agent it is more likely that broad immunological dysfunctions, such as abnormal NK cellular responses, could explain these findings.

This present study shows distinct and significant physiological differences in NK cell responses in children with ASD. We clearly demonstrate that there are profound abnormalities in NK cell function in young children recently diagnosed with ASD. An altered NK cell population may have several consequences which could impact upon immune function in ASD and could explain some of the immune findings previously observed in ASD. In addition, fetal/neonatal NK cells may have important roles in neuroimmune interactions during early brain development. Significant differences in NK cells may thus represent a susceptibility factor for ASD. Although NK cells are known for their rapid response to virally infected cells (Andoniou et al., 2006), the current study cannot determine a role for infection in ASD, rather that there is significant abnormality in the resting state and response of NK cells to stimulation. NK-related mechanisms for ASD development must be carefully determined in future studies. Such studies will need to examine gene expression and NK function in the same children in order to determine whether the dysregulated expression profile directly correlates with abnormal NK cell-mediated function. Nonetheless, these results indicate a clear and significant alteration in the gene expression and NK cell function in young children with ASD, a finding that may provide critical insight into potential neuroimmune susceptibility factors in some cases of ASD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the children and families who participated in this study. We also would like to acknowledge the staff of the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute and CHARGE study for their technical support and expertise. This work was funded by the NIEHS Children’s Center grant ( 2 P01 ES011269), US EPA STAR program grant (R833292 and R829388), NIEHS CHARGE study (R01ES015359) the Cure Autism Now Foundation, Peter Emch Foundation, Ted Lindsey Foundation, a grant awarded to Dr. Ashwood from the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute, and a generous gift from the Johnson family.

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- PDD

pervasive developmental disorder

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andoniou CE, Andrews DM, Degli-Esposti MA. Natural killer cells in viral infection: more than just killers. Immunological reviews. 2006;214:239–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Anthony A, Pellicer AA, Torrente F, Walker-Smith JA, Wakefield AJ. Intestinal lymphocyte populations in children with regressive autism: evidence for extensive mucosal immunopathology. J Clin Immunol. 2003;23:504–517. doi: 10.1023/b:joci.0000010427.05143.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Anthony A, Torrente F, Wakefield AJ. Spontaneous mucosal lymphocyte cytokine profiles in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms: mucosal immune activation and reduced counter regulatory interleukin-10. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:664–673. doi: 10.1007/s10875-004-6241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Is autism an autoimmune disease? Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Wakefield AJ. Immune activation of peripheral blood and mucosal CD3+ lymphocyte cytokine profiles in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2006;173:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Wills S, Van de Water J. The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006 doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR) American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Inc; Arlington, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barakonyi A, Rabot M, Marie-Cardine A, Aguerre-Girr M, Polgar B, Schiavon V, Bensussan A, Le Bouteiller P. Cutting edge: engagement of CD160 by its HLA-C physiological ligand triggers a unique cytokine profile secretion in the cytotoxic peripheral blood NK cell subset. J Immunol. 2004;173:5349–5354. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweig D, Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Croen LA, Pessah IN, Van de Water J. Autism: maternally derived antibodies specific for fetal brain proteins. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanlit M, Wills S, Goines P, Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Brain-specific Autoantibodies in the Plasma of Subjects with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1107:92–103. doi: 10.1196/annals.1381.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess S. Autism in children with congenital rubella. Journal of autism and childhood schizophrenia. 1971;1:33–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01537741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohly HH, Panja A. Immunological findings in autism. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2005;71:317–341. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(05)71013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comi AM, Zimmerman AW, Frye VH, Law PA, Peeden JN. Familial clustering of autoimmune disorders and evaluation of medical risk factors in autism. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:388–394. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly AM, Chez M, Streif EM, Keeling RM, Golumbek PT, Kwon JM, Riviello JJ, Robinson RG, Neuman RJ, Deuel RM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and autoantibodies to neural antigens in sera of children with autistic spectrum disorders, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, and epilepsy. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly AM, Chez MG, Pestronk A, Arnold ST, Mehta S, Deuel RK. Serum autoantibodies to brain in Landau-Kleffner variant, autism, and other neurologic disorders. J Pediatr. 1999;134:607–613. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends in immunology. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen LA, Braunschweig D, Haapanen L, Yoshida CK, Fireman B, Grether JK, Kharrazi M, Hansen RL, Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Maternal Mid-Pregnancy Autoantibodies to Fetal Brain Protein: The Early Markers for Autism Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, Odouli R, Van de Water J. Maternal autoimmune diseases, asthma and allergies, and childhood autism spectrum disorders: a case-control study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159:151–157. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croonenberghs J, Wauters A, Devreese K, Verkerk R, Scharpe S, Bosmans E, Egyed B, Deboutte D, Maes M. Increased serum albumin, gamma globulin, immunoglobulin IgG, and IgG2 and IgG4 in autism. Psychol Med. 2002;32:1457–1463. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czlonkowska A, Ciesielska A, Gromadzka G, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I. Estrogen and cytokines production - the possible cause of gender differences in neurological diseases. Current pharmaceutical design. 2005;11:1017–1030. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deykin EY, MacMahon B. Viral exposure and autism. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:628–638. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112726. Dec18200606:18200634:18200627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybkaer K, Iqbal J, Zhou G, Geng H, Xiao L, Schmitz A, d’Amore F, Chan WC. Genome wide transcriptional analysis of resting and IL2 activated human natural killer cells: gene expression signatures indicative of novel molecular signaling pathways. BMC genomics. 2007;8:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Wingert HD, Ho HH, Mickelson EC. Screening for autism spectrum disorders with the social communication questionnaire. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:S95–S103. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 10):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadient RA, Patterson PH. Leukemia inhibitory factor, Interleukin 6, and other cytokines using the GP130 transducing receptor: roles in inflammation and injury. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 1999;17:127–137. doi: 10.1002/stem.170127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin ME, Haselwood D, Dorshkind K, Castles JJ. Altered responsiveness to mitogens in subgroups of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of clinical & laboratory immunology. 1979;1:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JH, Jarskog LF, Vadlamudi S. Maternal poly I:C exposure during pregnancy regulates TNF alpha, BDNF, and NGF expression in neonatal brain and the maternal-fetal unit of the rat. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2005;159:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:613–627. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg JP, Lit L, Baron CA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Walker WL, Davis RA, Croen LA, Ozonoff S, Hansen R, Pessah IN, Sharp FR. Gene Expression Changes in Children with Autism. Genomics. 2008;91:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto I, Croen LA, Hansen R, Jones CR, van de Water J, Pessah IN. The CHARGE study: An epidemiological investigation of genetic and environmental factors contributing to autism. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114:1119–1125. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante-Duarte C, Weber A, Kratzschmar J, Prozorovski T, Pikol S, Hamann I, Bellmann-Strobl J, Aktas O, Dorr J, Wuerfel J, Sturzebecher CS, Zipp F. Frequency of blood CX3CR1-positive natural killer cells correlates with disease activity in multiple sclerosis patients. Faseb J. 2005;19:1902–1904. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3832fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie HB, Sarvetnick N. The role of NK cells and NK cell receptors in autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity. 2004;37:147–153. doi: 10.1080/0891693042000196174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Hall H, Berg L, Hoglund P. NK cells in autoimmune disease. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2006;298:259–277. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyonouchi H, Sun S, Le H. Proinflammatory and regulatory cytokine production associated with innate and adaptive immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental regression. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2001;120:170–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrukoff LF, Morgan NG, Zecchini D, White R, Petkau AJ, Satoh J, Paty DW. A role for natural killer cells in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1998;86:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. CDC: autism spectrum disorders common. JAMA. 2007;297:940. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.9.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen KL, Gregersen R, Meldgaard M, Clausen BH, Heibol EK, Ladeby R, Knudsen J, Frandsen A, Owens T, Finsen B. A role for interferon-gamma in focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2004;63:942–955. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lit L, Gilbert DL, Walker W, Sharp FR. A subgroup of Tourette’s patients overexpress specific natural killer cell genes in blood: a preliminary report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:958–963. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Pickles A, McLennan J, Rutter M, Bregman J, Folstein S, Fombonne E, Leboyer M, Minshew N. Diagnosing autism: analyses of data from the Autism Diagnostic Interview. J Autism Dev Disord. 1997;27:501–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1025873925661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler MF, Kessler JA. Cytokines in brain development and function. Advances in protein chemistry. 1998;52:223–251. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy CA, Morrow AL, Meinzen-Derr J, Schleifer K, Dienger K, Manning-Courtney P, Altaye M, Wills-Karp M. Elevated cytokine levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2006;172:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Money J, Bobrow NA, Clarke FC. Autism and autoimmune disease: a family study. Journal of autism and childhood schizophrenia. 1971;1:146–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01537954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, Nedergaard NJ. Autoimmune diseases in parents of children with infantile autism: a case-control study. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2007;49:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhle R, Trentacoste SV, Rapin I. The genetics of autism. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e472–486. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehus R, Lord C. Early medical history of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:S120–127. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odell D, Maciulis A, Cutler A, Warren L, McMahon WM, Coon H, Stubbs G, Henley K, Torres A. Confirmation of the association of the C4B null allelle in autism. Human immunology. 2005;66:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Tanaka K, Ishii A, Nakamura Y, Kondo S, Sugamura K, Takano S, Nakamura M, Nagata K. A nnovel serum protein that is selectively produced by cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2001;166:6404–6412. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellett F, Siannis F, Vukin I, Lee P, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD. KIRs and autoimmune disease: studies in systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma. Tissue antigens. 2007;69(Suppl 1):106–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.762_6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi D, Wang C, Mao X, Lendor C, Rothman PB, Miller RL. Antigen-specific immune responses to influenza vaccine in utero. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:1637–1646. doi: 10.1172/JCI29466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen NJ, Yoshida CK, Croen LA. Infection in the first 2 years of life and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e61–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal BM. The role of natural killer cells in curbing neuroinflammation. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2007;191:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Fatemi SH, Sidwell RW, Patterson PH. Maternal influenza infection causes marked behavioral and pharmacological changes in the offspring. J Neurosci. 2003;23:297–302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00297.2003. Jul 211 2006 2006:2031:2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SC, Correia C, Fesel C, Barreto M, Coutinho AM, Marques C, Miguel TS, Ataide A, Bento C, Borges L, Oliveira G, Vicente AM. Autoantibody repertoires to brain tissue in autism nuclear families. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2004;152:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK. Plasma increase of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma. Pathological significance in autism. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1996;66:143–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(96)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK, Rivas WH. Prevalence of serum antibodies to caudate nucleus in autistic children. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK, Warren R, Averett R, Ghaziuddin M. Circulating autoantibodies to neuronal and glial filament proteins in autism. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17:88–90. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar DA, Shao Y, Haines JL, Stenger JE, Jaworski J, Martin ER, DeLong GR, Moore JH, McCauley JL, Sutcliffe JS, Ashley-Koch AE, Cuccaro ML, Folstein SE, Gilbert JR, Pericak-Vance MA. Analysis of the RELN gene as a genetic risk factor for autism. Molecular psychiatry. 2005;10:563–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs EG, Ash E, Williams CP. Autism and congenital cytomegalovirus. J Autism Dev Disord. 1984;14:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02409660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs EG, Crawford ML. Depressed lymphocyte responsiveness in autistic children. Journal of autism and childhood schizophrenia. 1977;7:49–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01531114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten TL, Posey DJ, McDougle CJ. High blood monocyte counts and neopterin levels in children with autistic disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160:1691–1693. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Paterson AD, Zwaigenbaum L, Roberts W, Brian J, Liu XQ, Vincent JB, Skaug JL, Thompson AP, Senman L, Feuk L, Qian C, Bryson SE, Jones MB, Marshall CR, Scherer SW, Vieland VJ, Bartlett C, Mangin LV, Goedken R, Segre A, Pericak-Vance MA, Cuccaro ML, Gilbert JR, Wright HH, Abramson RK, Betancur C, Bourgeron T, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Buxbaum JD, Davis KL, Hollander E, Silverman JM, Hallmayer J, Lotspeich L, Sutcliffe JS, Haines JL, Folstein SE, Piven J, Wassink TH, Sheffield V, Geschwind DH, Bucan M, Brown WT, Cantor RM, Constantino JN, Gilliam TC, Herbert M, Lajonchere C, Ledbetter DH, Lese-Martin C, Miller J, Nelson S, Samango-Sprouse CA, Spence S, State M, Tanzi RE, Coon H, Dawson G, Devlin B, Estes A, Flodman P, Klei L, McMahon WM, Minshew N, Munson J, Korvatska E, Rodier PM, Schellenberg GD, Smith M, Spence MA, Stodgell C, Tepper PG, Wijsman EM, Yu CE, Roge B, Mantoulan C, Wittemeyer K, Poustka A, Felder B, Klauck SM, Schuster C, Poustka F, Bolte S, Feineis-Matthews S, Herbrecht E, Schmotzer G, Tsiantis J, Papanikolaou K, Maestrini E, Bacchelli E, Blasi F, Carone S, Toma C, Van Engeland H, de Jonge M, Kemner C, Koop F, Langemeijer M, Hijimans C, Staal WG, Baird G, Bolton PF, Rutter ML, Weisblatt E, Green J, Aldred C, Wilkinson JA, Pickles A, Le Couteur A, Berney T, McConachie H, Bailey AJ, Francis K, Honeyman G, Hutchinson A, Parr JR, Wallace S, Monaco AP, Barnby G, Kobayashi K, Lamb JA, Sousa I, Sykes N, Cook EH, Guter SJ, Leventhal BL, Salt J, Lord C, Corsello C, Hus V, Weeks DE, Volkmar F, Tauber M, Fombonne E, Shih A. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Miyake S, Kondo T, Terao K, Hatakenaka M, Hashimoto S, Yamamura T. Natural killer type 2 bias in remission of multiple sclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;107:R23–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazzano G, Zanzi D, Palomba C, Carbone E, Grimaldi S, Pisanti S, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, Ruggiero G. Differential involvement of CD40, CD80, and major histocompatibility complex class I molecules in cytotoxicity induction and interferon-gamma production by human natural killer effectors. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2002;72:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilaganathan B, Abbas A, Nicolaides KH. Fetal blood natural killer cells in human pregnancy. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 1993;8:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RD, Hickok JM, Anderson GM, Cohen DJ. Antibrain antibodies in infantile autism. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:644–647. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Slik AR, Alizadeh BZ, Koeleman BP, Roep BO, Giphart MJ. Modelling KIR-HLA genotype disparities in type 1 diabetes. Tissue antigens. 2007;69(Suppl 1):101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.762_5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Annals of neurology. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Cook EH., Jr Molecular genetics of autism spectrum disorder. Molecular psychiatry. 2004;9:819–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervliet G, Schandene L. In vitro correction of the interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma defect in multiple sclerosis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1985;61:556–561. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva J, Lee S, Giannini EH, Graham TB, Passo MH, Filipovich A, Grom AA. Natural killer cell dysfunction is a distinguishing feature of systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis research & therapy. 2005;7:R30–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RP, Foster A, Margaretten NC. Reduced natural killer cell activity in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26:333–335. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RP, Margaretten NC, Pace NC, Foster A. Immune abnormalities in patients with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1986;16:189–197. doi: 10.1007/BF01531729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RP, Singh VK, Cole P, Odell JD, Pingree CB, Warren WL, White E. Increased frequency of the null allele at the complement C4b locus in autism. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1991;83:438–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills S, Cabanlit M, Bennett J, Ashwood P, Amaral D, Van de Water J. Autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorder. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1107:79–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1381.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yovel G, Sirota P, Mazeh D, Shakhar G, Rosenne E, Ben-Eliyahu S. Higher natural killer cell activity in schizophrenic patients: the impact of serum factors, medication, and smoking. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2000;14:153–169. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1999.0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman AW, Connors SL, Matteson KJ, Lee LC, Singer HS, Castaneda JA, Pearce DA. Maternal antibrain antibodies in autism. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2007;21:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman AW, Jyonouchi H, Comi AM, Connors SL, Milstien S, Varsou A, Heyes MP. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum markers of inflammation in autism. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;33:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]