Abstract

Objectives. I examined the role of community-level factors in the reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young people aged 15 to 24 years in 3 African countries with varying HIV prevalence rates.

Methods. I analyzed demographic and health survey data from Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Zambia during the period 2001 through 2003 to identify individual, household, and community factors associated with reports of risky sexual behaviors.

Results. The mechanisms through which the community environment shaped sexual behaviors varied among young men and young women. Community demographic profiles were not associated with reports of risky sexual behavior among young women but were influential in shaping the behavior of young men. Prevailing economic conditions and the behaviors and attitudes of adults in the community were strong influences on young people's sexual behaviors.

Conclusions. These results provide strong support for a focus on community-level influences as an intervention point for behavioral change. Such interventions, however, should recognize specific cultural settings and the different pathways through which the community can shape the sexual behaviors of young men and women.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa are home to only 10% of the world's population but account for approximately 85% of AIDS deaths worldwide.1,2 Previous studies have highlighted high levels of sexual activity among young people (i.e., those aged 15–24 years) in many sub-Saharan African countries,3–7 paralleled by increasing rates of HIV infection among young people.1,8,9 Although young people in these countries have been shown to have high levels of knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS, studies have demonstrated significant deviation between such knowledge and reported sexual behaviors,10–12 with high levels of risky sexual activity reported (e.g., failing to use a condom,13 engaging in transactional sex,13,14 having multiple partners.3,6,15).

The health hazards associated with sexual risk taking among young people are well documented, but little is known about the factors associated with sexual behaviors among adolescents in developing countries.13,15–20 In the few studies that have examined young people's sexual behavior in these countries, a micro-level approach has been adopted, with a focus on individual characteristics as predictors of behavior21 and little consideration of the potential pathways through which the wider community may shape behavior.

Condom use has often been the outcome of interest in studies of adolescent sexual behavior,7,22–25 which is not surprising given the emphasis of many HIV prevention strategies on promoting condom use; other studies have examined factors associated with sexual activity or sexual debut.1,15,17,26 Higher levels of risky sexual activity have been shown among young people (both male and female) and adult men24,26 than among adult women.4,6,27 In many sub-Saharan African countries, young women's lack of negotiating power in sexual relationships is influenced by the large age differences common in many relationships,3,14,27,28 the presence of violence or coercion,25 and economic incentives to participate in risky sexual activities.14

Educational attainment has been shown to be associated with young people's sexual behaviors.5–7,29 This relationship is more than simply a function of increased knowledge leading to positive health behaviors; the type of educational institution attended and the place of residence of the student have been shown to be influential in determining sexual behaviors,5 suggesting that these behaviors are also influenced by the degree of freedom afforded to the young person.

Young women from poor households have been shown to be at particular risk of sexual risk taking, with their economic status motivating them to partake in transactional sex and serving as another limitation in their negotiating power with respect to condom use.6,14 In terms of the influence of knowledge on behavior, some studies have demonstrated a disparity between knowledge regarding HIV risk and sexual behavior12,22,30 such that many young people, despite knowing the risks associated with unprotected sexual activities, still engage in these activities. There is a limited amount of evidence suggesting that risk knowledge is a more protective factor against risky sexual activity among women than among men,31 with fear of unplanned pregnancy providing a greater deterrent for women than for men.

Although much is known about the individual characteristics associated with sexual risk taking among young people, the role of the community in shaping such behaviors has been largely overlooked. In a study of adolescents residing in the United States, Billy et al.21 suggested that young people's sexual behavior is strongly influenced by a community's opportunity structure (i.e., presence of social and economic opportunities), which is composed of 3 key elements. The first element is the presence in the community of reproductive and sexual health services, which determines a young person's access to information and services. The second element is the demographic profile of the community, which determines the presence of potential sexual partners. The final element is the presence or absence of economic or social opportunities, which influences young people's perceptions regarding the opportunity costs of sexual behavior.

Studies testing the theory of Billy et al. have largely been restricted to developed countries.21,32 Although some studies have addressed the influence of community factors on young people's sexual behavior in developing countries, these investigations have focused primarily on indicators of the presence of economic opportunities for young people,33,34 failing to examine the roles of the cultural and social environments in shaping behavior.

I examined community-level factors associated with risky sexual behaviors among young people in the African countries of Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Zambia. The goal of the study was to advance understanding of how the community environment shapes young people's sexual behavior by considering a broad range of potential community influences, including social, behavioral, and demographic dimensions of the community environment.

METHODS

Study Settings

Demographic and health indicators for Burkina Faso are poor; 46% of the population is younger than 14 years, and the HIV prevalence rate is 6.5%. Literacy rates (among residents older than 15 years) are low, only 17% and 37% among men and women, respectively.35

Demographic and health indicators are more favorable in Ghana than in the other 2 study countries; 38% of the country's citizens are younger than 14 years, and the HIV prevalence rate is 3.1%. Literacy rates are comparable to those found in Zambia: 83% among men and 67% among women.36

In Zambia, 46% of residents are younger than 14 years, and the low life expectancy at birth—only 35 years—reflects the significant impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic; the prevalence of HIV in the adult population is 16.5%, as compared with 6.5% and 3.1% in Burkina Faso and Ghana, respectively. Literacy rates are higher in Zambia than in the other 2 study countries: 87% among men and 75% among women.37

Data

The data I used were derived from demographic and health surveys conducted in the 3 study countries (Burkina Faso in 2003, Ghana in 2003, and Zambia in 2001–2002). The 3 countries were selected from the 24 African countries for which demographic and health survey data (1) were available within the 5 years preceding my study and (2) included comparable modules on sexual behavior. The original 24 countries were stratified according to HIV prevalence rate: less than 5% (9 countries), 5% to 10% (8 countries), and more than 11% (7 countries). One country was selected from each of these categories on the basis of the country's social and economic characteristics as well as my experience in working with these data sets previously and conducting research in the study countries.

In the demographic and health surveys examined, separate stratified multistage cluster designs were used to collect nationally representative data, in both rural and urban areas, on women of reproductive age (15–45 years) and men (aged 15–59 years). The nonresponse rate among women ranged from 3% to 5% across the 3 countries. The samples used in the present analyses consisted of young women and men aged 15 to 24 years who reported that they had ever had sexual intercourse; sample sizes were 3105 in Burkina Faso (528 young men, 2577 young women), 3160 in Ghana (1022 young men, 2138 young women), and 2687 in Zambia (549 young men, 2138 young women).

The surveys collected data on number of sexual partners in the 12 months preceding the survey, relationship status with each partner, and condom use with each partner. The dependent variable in the present analysis was a binary variable coded 1 if the respondent reported having engaged in risky sexual activity (defined as sexual intercourse without condom use with 1 or more partners) in the 12 months before the survey and 0 if the respondent reported not having engaged in such activity in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Statistical Analysis

The hierarchical structure of each of the demographic and health survey data sets violated the assumption of independence of ordinary logistic regression models. A multilevel modeling technique was used to account for the hierarchical structure of the data and to facilitate estimation of community-level (i.e., primary sampling unit) influences on risky sexual behavior. This multilevel modeling strategy accommodated the hierarchical nature of the data and corrected estimated standard errors to allow for clustering of observations within units.38

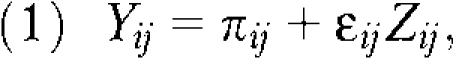

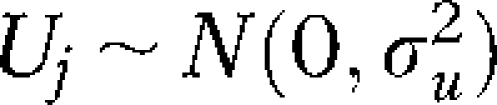

In addition, the multilevel models used allowed estimation of a random effect term representing the extent to which reporting of risky sexual behaviors varied across primary sampling units, thus providing a measure of community-level clustering of the outcome. The MLwiN software package version 2.02 (Center for Multilevel Modelling, Bristol, England) was used to fit separate multilevel logistic models for young men and women in each of the 3 countries.39 The models were written as follows:

|

where

Yij is a binary outcome (reporting of risky sexual behavior) for individual i in primary sampling unit j; Yij is assumed to be an independent Bernoulli random variable with the probability of reporting of risky sexual behavior πij = PR(Yij = 1). Consequently, to correctly specify the binomial variation, Zij denotes the square root of the expected binomial variance of πij, and the variance of the individual residual term ϵij is constrained to be 1. The outcome variable loge(πij/[1 − πij]) fit in the model was the loge odds of risky sexual behavior versus no risky sexual behavior. This constrained the predicted values from the model to be between 0 and 1. The α term is a constant, whereas B is the vector of parameters corresponding to the vector of potential explanatory factors defined as Xij. The primary sampling unit (level 2) residual term is defined as  . The same independent variables were entered into all 6 models.

. The same independent variables were entered into all 6 models.

Three levels of potential influence on risky sexual behavior were considered: individual, household, and community. Individual- and household-level data were derived from the individual questionnaires administered separately to male and female respondents. Selection of individual and household independent variables was informed by previous studies on factors influencing adolescent sexual behavior. Because community survey information was not available, community-level data were derived from individual responses. This process involved aggregating individual-level data to the community level (minus the index response) to form proxy community measures.

The choice of community-level variables was guided by the 3 community dimensions (i.e., demographic profile, paths to future mobility, community health services) suggested by Billy et al.21 as influential in shaping adolescent behavior. In this study, the demographic profile of the community was represented by 3 variables: mean age at first delivery among women in the community, mean age at first marriage among women in the community, and mean number of children born to women in the community. The nature of paths to future mobility dimension was represented by the following variables: the percentage of men and women in the community who were employed and the percentage of men and women in the community with at least a primary education. The 3 countries’ demographic and health surveys did not include information on presence of sexual or reproductive health services in the community, and thus this element was not captured in the present analysis.

In addition to the dimensions proposed by Billy et al.,21 behavioral traits prevalent in the community were considered in an effort to identify how the behaviors of adults in the community influenced the sexual behaviors of young people. Thus, individual responses from community residents older than 35 years were aggregated to create community-level behavioral variables, and these responses were linked, via community identifiers, to young people's data. The community-level behavioral factors tested were mean age at first intercourse, level of knowledge about HIV/AIDS, and attitudes toward HIV-positive individuals among men and women older than 35 years. Only variables that were statistically significant in at least 1 country for young women or young men were included in the final analysis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Individual, Household, and Community Characteristics Included in the Final Analysis Among Young Men and Women: Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Zambia, 2001–2003

| Burkina Faso |

Ghana |

Zambia |

||||

| Characteristic | Young Men (n = 528) | Young Women (n = 2577) | Young Men (n = 1022) | Young Women (n = 2138) | Young Men (n = 549) | Young Men (n = 2138) |

| Individual level | ||||||

| Age, y, % | ||||||

| 15–19 | 35.4 | 38.3 | 29.5 | 32.3 | 51.2 | 41.2 |

| 20–24 | 64.6 | 61.7 | 70.5 | 67.6 | 48.8 | 58.8 |

| Educational level, % | ||||||

| No education | 48.2 | 70.9 | 11.8 | 24.2 | 3.0 | 12.4 |

| Primary | 25.8 | 16.1 | 19.2 | 22.0 | 56.6 | 57.7 |

| Secondary or higher | 26.0 | 13.0 | 69.0 | 52.8 | 40.4 | 29.9 |

| Married | 22.8 | 78.8 | 26.1 | 60.3 | 18.8 | 66.4 |

| Employed | 35.5 | 80.1 | 35.2 | 63.3 | 52.9 | 47.9 |

| No. of household members, mean (range) | 9.5 (1–34) | 8.8 (1–37) | 3.9 (1–40) | 5.4 (1–22) | 6.8 (1–22) | 6.2 (1–26) |

| Has a child, % | 13.3 | 62.7 | 16.5 | 51.8 | 17.6 | 68.3 |

| Has final say in personal decisions concerning health, % | 28.3 | 86.7 | 42.7 | 59.9 | … | … |

| Knowledge about AIDS, mean score (range)a | 4.2 (0–7) | 1.4 (0–7) | 3.9 (0–7) | 3.5 (0–7) | 4.1 (0–6) | 3.9 (0–6) |

| Household level | ||||||

| Ownership of assets, mean score (range)b | 1.8 (0–5) | 1.7 (0–5) | 2.1 (0–5) | 2.0 (0–5) | 2.2 (0–5) | 2.1 (0–5) |

| Community level | ||||||

| Age at marriage among women, y, mean (range) | 17.9 (13–24) | 17.9 (13–24) | 19.1 (11–31) | 19.1 (11–31) | 17.5 (11–29) | 17.5 (11–29) |

| Socioeconomic profile, % | ||||||

| Men employed | 65.2 | 65.2 | 69.8 | 69.8 | 58.5 | 58.5 |

| Men with at least a primary education | 51.3 | 51.3 | 83.7 | 83.7 | 95.2 | 95.2 |

| Women employed | 81.4 | 81.4 | 61.6 | 61.6 | 52.3 | 52.3 |

| Women with at least a primary education | 72.1 | 72.1 | 73.4 | 73.4 | 86.4 | 86.4 |

| Behavioral profile | ||||||

| Knowledge about AIDS among adult women in community, mean score (range)a | 3.4 (0–5) | 3.4 (0–5) | 3.4 (0–5) | 3.4 (0–5) | 4.2 (0–6) | 4.2 (0–6) |

| Attitudes toward AIDS among adult women in community, mean score (range)c | 0.7 (0–4) | 0.7 (0–4) | 1.8 (0–4) | 1.8 (0–4) | 0.8 (0–2) | 0.8 (0–2) |

| Attitudes toward AIDS among adult men in community, mean score (range) | 1.2 (0–4) | 1.2 (0–4) | 1.4 (0–4) | 1.4 (0–4) | 0.7 (0–2) | 0.7 (0–2) |

Index ranges from 0 to 7 and includes awareness of AIDS, knowledge that a healthy person can be HIV positive, knowledge of mother-to-child transmission, and knowledge that abstinence, condom use, limiting numbers of sexual partners, and monogamy are ways to prevent HIV.

Index ranges from 0 to 5 and comprises radio, clock, television, motor vehicle, and bicycle ownership.

Index ranges from 0 to 4 in Burkina Faso and Ghana and from 0 to 2 in Zambia.

RESULTS

Self-reported sexual behaviors varied by gender and country. Very few young women reported having had more than 1 sexual partner in the preceding 12 months (7% in Burkina Faso, 3% in Ghana, 4% in Zambia), and relatively low percentages reported having used a condom during their most recent sexual activity (18% in Burkina Faso, 18% in Ghana, and 19% in Zambia). By contrast, there was greater reporting of multiple recent sex partners among men (17% in Burkina Faso, 12% in Ghana, and 20% in Zambia), as well as higher rates of condom use during most recent sexual intercourse (45% in Burkina Faso, 57% in Ghana, and 64% in Zambia). Mean age at first intercourse was higher among young women (18 years) than young men (17 years) in Burkina Faso and Ghana and the same among young men and women in Zambia (15 years).

In terms of sociodemographic factors, age was not significantly associated with reports of sexual behavior (Tables 2 and 3) with the exception of Burkina Faso, where young women aged 20 to 24 years were less likely than were young women aged 15 to 19 years to report risky sexual behaviors. Odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors were significantly reduced among young women in Ghana and Zambia who had children, but having a child was not associated with reports of risky sexual behaviors among young men in any of the countries. In all 3 countries, married women were significantly less likely than were unmarried women to report risky sexual behaviors; conversely, in Burkina Faso and Zambia, married men were significantly more likely than were unmarried men to report risky behaviors.

TABLE 2.

Results of Multilevel Logistic Models Regarding Reports of Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Young Women: Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Zambia, 2001–2003

| Characteristic | Burkina Faso, OR (95% CI) | Ghana, OR (95% CI) | Zambia, OR (95% CI) |

| Individual level | |||

| Age 20–24 y | 0.55* (0.37, 0.81) | 0.84 (0.57, 1.23) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.24) |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 0.82* (0.53, 1.27) | 1.18 (0.64, 2.27) | 1.18 (0.70, 1.96) |

| Secondary or higher | 0.37* (0.21, 0.63) | 0.84* (0.46, 1.53) | 0.48* (0.26, 0.87) |

| Married | 0.02* (0.01, 0.04) | 0.17* (0.10, 0.27) | 0.05* (0.04, 0.08) |

| Employed | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07) | 0.87 (0.59, 1.26) | 1.46* (1.08, 1.97) |

| High no. of household members | 1.03* (1.01, 1.06) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) |

| Has a child | 0.71 (0.45, 1.11) | 0.29* (0.18, 0.47) | 0.54* (0.39, 0.76) |

| Has final say in personal decisions concerning health | 0.55* (0.34, 0.91) | 0.47* (0.32, 0.69) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.56) |

| High knowledge-about-AIDS score | 0.84* (0.73, 0.96) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.31) | 0.91 (0.85, 1.78) |

| Household level | |||

| Ownership of assets score | 0.84* (0.76, 0.94) | 0.79* (0.69, 0.91) | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) |

| Community level | |||

| Mean age at marriage among women | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.14) |

| Socioeconomic profile | |||

| Percentage of men employed | 1.48 (0.72, 3.01) | 3.54* (1.19, 10.57) | 0.68 (0.36, 1.27) |

| Percentage of men with at least a primary education | 0.90* (0.81, 0.99) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.06) |

| Percentage of women employed | 1.54 (0.28, 8.51) | 4.30* (1.19, 15.44) | 3.07* (1.53, 6.18) |

| Percentage of women with at least a primary education | 0.99 (0.80, 1.22) | 0.87 (0.76, 1.10) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) |

| Behavioral profile | |||

| Mean knowledge-about-AIDS score among adult women in community | 0.83 (0.62, 1.10) | 1.14 (0.83, 1.56) | 0.75* (0.57, 0.99) |

| Mean attitudes-toward-AIDS score among adult women in community | 1.25 (0.66, 2.36) | 0.88 (0.64, 1.22) | 0.73 (0.48, 1.10) |

| Mean attitudes-toward-AIDS score among adult men in community | 0.74* (0.59, 0.95) | 0.71* (0.50, 0.99) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.44) |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Random intercept terms were as follows: Burkina Faso, 0.008 (SE = 0.001; P < .05); Ghana, 0.003 (SE = 0.001; P < .05); and Zambia, 0.009 (SE = 0.001; P < .05).

P < .05.

TABLE 3.

Results of Multilevel Logistic Models Regarding Reports of Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Young Men: Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Zambia, 2001–2003

| Characteristic | Burkina Faso, OR (95% CI) | Ghana, OR (95% CI) | Zambia, OR (95% CI) |

| Individual level | |||

| Age 20–24 y | 1.25 (0.80, 1.96) | 0.86 (0.52, 1.41) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.18) |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 0.79 (0.47, 1.32) | 1.14 (0.48, 2.71) | 1.12 (0.37, 3.73) |

| Secondary or higher | 0.82 (0.45, 1.48) | 0.37* (0.16, 0.85) | 0.64 (0.20, 2.01) |

| Married | 5.78* (2.39, 14.01) | 1.29 (0.74, 2.32) | 4.37* (2.12, 9.00) |

| Employed | 0.60* (0.38, 0.94) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.40) | 0.51* (0.35, 0.76) |

| High no. of household members | 1.01 (0.94, 1.04) | 0.95* (0.90, .099) | 0.95* (0.90, 0.99) |

| Has a child | 0.57 (0.21, 1.56) | 2.10 (1.03, 4.31) | 1.41 (0.71, 2.81) |

| Has final say in personal decisions concerning health | 1.32 (0.79, 2.20) | 0.83 (0.53, 1.30) | …a |

| High knowledge-about-AIDS score | 0.86* (0.74, 0.95) | 0.96 (0.80, 1.15) | 0.75* (0.63, 0.89) |

| Household level | |||

| Ownership of assets score | 0.80* (0.67, 0.94) | 0.86* (0.74, 0.99) | 0.87* (0.63, 0.98) |

| Community level | |||

| Mean age at marriage among women | 1.27* (1.04, 1.54) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) | 1.16* (1.04, 1.31) |

| Socioeconomic profile | |||

| Percentage of men employed | 0.24* (0.08, 0.67) | 1.59 (0.44, 5.69) | 0.42 (0.16, 1.18) |

| Percentage of men with at least a primary education | 0.86* (0.73, 0.99) | 1.06 (0.93, 1.21) | 0.89 (0.77, 1.02) |

| Percentage of women employed | 3.36 (0.43, 7.64) | 1.34 (0.37, 4.83) | 1.17 (0.76, 4.64) |

| Percentage of women with at least a primary education | 0.95 (0.74, 1.23) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.09) | 0.80* (0.77, 0.93) |

| Behavioral profile | |||

| Mean knowledge-about-AIDS score among adult women in community | 0.62* (0.31, 0.94) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.49) | 0.16* (0.05, 0.34) |

| Mean attitudes-toward-AIDS score among adult women in community | 0.49* (0.15, 0.72) | 0.91 (0.63, 1.34) | 0.82 (0.47, 1.42) |

| Mean attitudes-toward-AIDS score among adult men in community | 0.84 (0.63, 1.14) | 0.82 (0.56, 1.19) | 0.43* (0.29, 0.63) |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Random intercept terms were as follows: Burkina Faso, 0.009 (SE = 0.001: P < .05); Ghana, 0.323 (SE = 0.173); and Zambia, 0.473 (SE = 0.251).

Data not collected in Zambia.

P < .05.

The influence of educational attainment, employment status, and household wealth on risky sexual behavior varied by country and gender. In all 3 countries, young women with a secondary or higher level of education were less likely than were those with no education to report risky sexual behaviors; however, there was no association between a primary-level education and reports of risky sexual behaviors. Among young men, a significant relationship between educational attainment and reports of risky sexual behavior was observed only among those in Ghana with a secondary-level education. In Burkina Faso and Zambia, young men who were employed were significantly less likely than were young men who were not employed to report risky sexual behaviors; in Zambia, young women who were employed were more likely to report risky sexual behaviors.

Household wealth (assessed with respect to ownership of household goods) was significantly associated with reduced odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors among young men and women in Burkina Faso and Ghana and among young men in Zambia. In Ghana and Zambia, a large household size exhibited a significant negative relationship with reports of risky sexual behavior among young men; in Burkina Faso, there was a significant positive relationship between living in a large household and reports of risky sexual behaviors.

Several indicators of knowledge and autonomy were also associated with reports of risky sexual behaviors. In Burkina Faso and Ghana, young women who reported that they had the final say in decisions concerning their health were significantly less likely than were those who did not report risky sexual behaviors; however, similar associations were not found among young men. Higher levels of HIV/AIDS-related knowledge were associated with significantly reduced odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors among young men and women in Burkina Faso and among young men in Zambia.

The community characteristics associated with reports of risky sexual behaviors also varied considerably by country and gender. Community demographic profiles were not significantly associated with reports of risky sexual behaviors among young women; however, among young men in Burkina Faso and Zambia, residence in a community in which women's mean age at marriage was high was associated with increased odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors.

Relationships between community employment and educational levels and reports of risky sexual behaviors varied. High male employment levels significantly decreased the odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors among young men in Burkina Faso. In Ghana, however, higher employment levels among both young men and young women were associated with increased reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young women; in Zambia, high female employment levels were associated with an increased reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young women.

There was evidence that higher community educational levels were related to reduced reporting of risky sexual behaviors. Residence in a community with high male educational attainment reduced reporting of risky sexual behaviors among both young men and young women in Burkina Faso, whereas high female educational attainment reduced reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young men in Zambia.

Greater levels of HIV/AIDS-related knowledge among women in the community older than 35 years were associated with reduced odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors among young men and women in Zambia and among young men in Burkina Faso. More-tolerant attitudes toward HIV-positive individuals among male adults in the community were associated with reduced odds of reporting risky sex among young women in Burkina Faso and Ghana and among young men in Zambia; similarly, more-tolerant attitudes toward those with HIV among female adults in the community were related to reduced reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young men in Burkina Faso.

After I controlled for all of the independent variables included in the models, the random effect term remained significant for young women in all 3 countries but was significant for young men only in Burkina Faso. Hence, certain elements of the community-level variation in reports of risky sexual behaviors remained unexplained for young women in all 3 countries and for young men in Burkina Faso.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate significant variations in factors associated with reports of risky sexual behavior among young people in 3 African countries with high HIV prevalence rates. There were strong gender differences with respect to factors influencing sexual behavior. The findings suggest disparate behavioral expectations for young men and young women; that is, only among young women were marriage and parenthood linked to expectations of fidelity. This situation raises concern with regard to the risk of within-couple HIV transmission if the male partner is engaging in risky sexual behaviors outside of the union. Furthermore, it poses a challenge for HIV intervention programs, which must tackle the dual issues of male sexual risk behaviors and barriers to condom use within married couples.40

There was an almost universal positive benefit of residence in a wealthy household, although the influence of employment on sexual risk taking varied among young men and women, pointing to the importance of economic factors in shaping young people's sexual behaviors. Much has been written of the commercialization of sexuality among young people, particularly young women, in sub-Saharan Africa.14,41,42 In settings in which there have traditionally been large age differences between marital partners and sexual partners, economic exchanges between wealthier men and young women have become an integral part of relationship development.14,41 As such, sexual encounters often include the exchange of money or gifts.14,43 Hence, economic gain may become a motivation for young women's entry into sexual activity, and the reliance on such economic gain may reduce even further their ability to negotiate condom use.

In a study of community influences on adolescent behavior in the United States, Brewster et al.32 noted that the community economic environment may shape behavior through its relationship to both perceived opportunities for attainment and the normative patterns of behavior that adolescents observe in adults around them. As such, young women living in wealthier communities may observe more opportunities for accruing human capital (for example, educational and employment opportunities), providing the motivation for avoidance of early sexual debut.

In this study, both being employed and living in a community with a large percentage of employed men were protective against risky sexual behavior among young men, probably reflecting the greater economic opportunities for men in these communities and the corresponding increased access to services and information. However, no protective effect of living in a wealthy community was observed among young women. In fact, there was evidence of a negative influence of a good economic environment on the sexual behavior of young women. Living in a community with high male employment levels increased the odds of reporting risky sex among young women in Ghana. The presence of relatively wealthy men in the community may increase women's likelihood of becoming involved in economically motivated sexual activity, and such activity is more likely to be risky.6,14

Among young women, being employed and living in a community in which a large percentage of women were employed were in many cases associated with increased reporting of risky sexual behaviors. Employment may remove young women from traditional family roles and provide them with greater opportunities to meet potential sexual partners. Also, in societies in which women's work is largely restricted to the home, women seeking employment outside of the home may be doing so as a result of economic desperation; thus, risky sexual behaviors among employed women may reflect a combination of greater social mixing and economic motivation to engage in such behaviors.

High community educational levels were associated with reduced odds of reporting risky sexual behaviors. In the case of women, there is undoubtedly an economic aspect to this relationship, with education providing greater opportunities and motivation to avoid early sexual debut. Higher educational attainment may also lead to increased access to information outside of the home, which, in combination with the experience gained through social mixing, may lead women to develop the functional autonomy necessary to make informed, healthful choices.

Living in a community with a high level of educational attainment may also provide a model of behavior against which young women can judge their decisions on sexual behavior; young women living in communities in which educational levels are high may have more opportunities to observe alternative patterns of behavior open to them and to identify pathways to accrue social and human capital. In this context, levels of educational attainment may reflect perceived paths for future mobility, suggested by Billy et al.21 to be influential in shaping behavior.

Residence in a community in which women's mean age at marriage was high was associated with increased reporting of risky sexual behaviors among young men. This unusual result may have been a product of increased opportunities for sexual partnering among young men; in communities with a high mean age at marriage among women, there are larger numbers of single young women and, hence, greater opportunities for men to find multiple sexual partners.

In some cases, living in a community in which adults had more-tolerant attitudes toward those living with HIV and in which women had more knowledge about HIV reduced the reporting of risky sexual behaviors. Tolerant and positive attitudes toward those with HIV are arguably the product of knowledge about and familiarity with HIV. The results observed here suggest that adults in more tolerant communities may be passing their knowledge of and attitudes toward HIV to younger people and, in so doing, discouraging them from engaging in risky sexual behaviors.

This study's most noteworthy finding involved the different impact of the community environment on the behaviors of young men and women, indicating that relationships between sexual behavior and prevailing economic and demographic conditions are mediated by gender differences in opportunities and expected behaviors. If there is to be a complete understanding of the factors influencing the sexual behaviors of young people, future work examining the interaction between gender and the social, cultural, and economic environment is necessary. In addition, further work is required to explore how young men and women perceive their community environment and to understand how their interpretation of their environment shapes their decisionmaking around sexual behavior.

Limitations

This study involved several limitations. For example, it relied on data derived from young people's self-reports of their sexual behaviors, and previous studies have suggested that young women are likely to underreport sexual activity and that young men are likely to overreport such activity.44,45 However, demographic and health surveys remain the only source of routinely collected data on young people's sexual behavior in Africa, and notwithstanding the potential for misreporting of behavior, the new information gained through the present analysis far outweighs this possible bias.

In addition, the community-level variables used in the analysis were derived from individual-level data as a result of the absence of comparable community-level data. As such, information on community health facilities and ongoing community educational and behavioral change activities is missing from the analysis, an absence that is probably reflected in the significant random effects terms.

Conclusions

As the HIV epidemic continues to surge among young people in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, development of effective behavioral change interventions is imperative; an understanding of the role of community characteristics is an integral step in this process. In this study, community-level influences on sexual behavior varied not only by gender but also by country, highlighting a pair of important points. The interaction between the community and the individual is different for young men and young women; often young men have greater freedom and young women are relegated to a vulnerable position. In addition, there is no single “community-level” influence on young people's sexual behavior; the ways in which community elements influence young people's behaviors are specific to cultural contexts, gender, and the characteristics of the community.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R03HD052431).

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Emory University.

References

- 1.Eaton L, Flisher AJ, Aaro LE. Unsafe sexual behavior in South African youth. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:149–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intensifying Action Against HIV/AIDS: Responding to the Development Crisis. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorgen R, Yansane M, Marx M, Millimounou D. Sexual behavior and attitudes among unmarried urban youths in Guinea. Int Fam Plann Perspect 1998;24:65–71 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etuck SJ, Ihejiamaizu EC, Etuck I. Female adolescent sexual behavior in Calabar, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2004;11:269–273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taffa N, Klepp KI, Sundby J, Bjune G. Psychosocial determinants of sexual activity and condom use intention among youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J STD AIDS 2002;1:714–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okafor I, Obi SN. Sexual risk behavior among undergraduate students in Enugu, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynecol 2005;25:592–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prata N, Vahidnia F, Fraser A. Gender and relationship differences in condom use among 15–24-year-olds in Angola. Int Fam Plann Perspect 2005;31:192–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Population Fund Annual report: program priorities—adolescent reproductive health. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/about/report/report97/adolescence.htm. Accessed June 9, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiapi-Iwa L, Hart GJ. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in Adjumani District, Uganda: qualitative study of the role of formal, informal and traditional health providers. AIDS Care 2004;16:339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glover EK, Bannerman A, Pence BW, et al. Sexual health experiences of adolescents in three Ghanaian towns. Int Fam Plann Perspect 2003;29:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James S, Reddy SP, Taylor M, Jinabhai CC. Young people, HIV/AIDS/STIs and sexuality in South Africa: the gap between awareness and behavior. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:264–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulton LA, Cullen R, Khalokho SW. Perceptions of the risks of sexual activity and their consequences among Ugandan adolescents. Stud Fam Plann 2000;31:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilika A, Anthony I. Unintended pregnancy among unmarried adolescents and young women in Anambra State, south east Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2004;8:92–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luke N. Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann 2003;34:67–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanc AK, Way AA. Sexual behavior and contraceptive knowledge and use among adolescents in developing countries. Stud Fam Plann 1998;29:106–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabin LS, Kiragu K. Health consequences of adolescent sexuality and fertility behavior in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann 1998;29:210–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta N, Mahy M. Sexual initiation among adolescent girls and boys: trends and differentials in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch Sex Behav 2003;32:41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Wulf D. Today's Adolescents, Tomorrow's Parents: A Portrait of the Americas. New York, NY: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gage AJ. An Assessment of the Quality of Data on Age at First Union, First Birth, and First Sexual Intercourse for Phase II of the Demographic and Health Surveys Program. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss E, Whelan D, Gupta GR. Vulnerability and Opportunity: Adolescents and HIV/AIDS in the Developing World. Washington, DC: International Center on Women; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billy JOG, Brewster KL, Grady W. Contextual effects on the sexual behavior of adolescent women. J Marriage Fam 1994;56:387–404 [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacPhail C, Campbell C. ‘I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things’: condom use among adolescents and young people in a southern African township. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1613–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meekers D, Klein M. Determinants of condom use among young people in urban Cameroon. Stud Fam Plann 2002;33:335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Betts S, Peterson D, Huebner AJ. Zimbabwean adolescents’ condom use: what makes a difference? Implications for intervention. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman S, O'Sullivan LF, Harrison A, Dolezal C, Monroe-Wise A. HIV risk behaviors and context of sexual coercion in young adults’ sexual interactions: results from a diary study in rural South Africa. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slap GB, Lot L, Huang B, Daniyam CA, Zink TM, Succop PA. Sexual behavior of adolescents in Nigeria: cross sectional survey of secondary school students. BMJ 2003;326:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet 2002;359:1896–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morojele NK, Brook JS, Kachienga MA. Perceptions of sexual risk behaviors and substance abuse among adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Care 2006;18:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Rossem R, Meekers D, Akinyemi Z. Consistent condom use with different types of partners: evidence from two Nigerian surveys. AIDS Educ Prev 2001;13:252–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnani RJ, Karim AM, Weiss LA, Bond KC, Lemba M, Morgan GT. Reproductive health risk and protective factors among youth in Lusaka, Zambia. J Adolesc Health 2002;30:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Sullivan LF, Udell W, Patel VL. Young urban adults’ heterosexual risk encounters and perceived risk and safety: a structured diary study. J Sex Res 2006;43:343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewster K, Billy JOG, Grady W. Social context and adolescent behavior: the impact of community on the transition to sexual activity. Soc Forces 1993;71:713–740 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman CE, Clark S, Manzini N, May J. Communities, opportunities, and adolescents’ sexual behavior in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Stud Fam Plann 2004;35:261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karim AM, Magnani RJ, Morgan GT, Bond KC. Reproductive health risk and protective factors among unmarried youth in Ghana. Int Fam Plann Perspect 2003;29:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Central Intelligence Agency The world fact book: Burkina Faso. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uv.html. Accessed June 9, 2008

- 36.Central Intelligence Agency The world fact book: Ghana. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gh.html. Accessed June 9, 2008

- 37.Central Intelligence Agency The world fact book: Zambia. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/za.html. Accessed June 9, 2008

- 38.Goldstein H. Multilevel Statistical Models. London, England: Edward Arnold; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Center for Multilevel Modelling. MLwiN. Available at: http://www.cmm.bristol.ac.uk. Accessed June 9, 2008.

- 40.Allen S, Lindan C, Serufilira A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in urban Rwanda: demographic and behavioral correlates in a representative sample of childbearing women. JAMA 1991;266:1657–1663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haram L. Negotiating sexuality in times of economic want: the young and modern Meru women. : Klepp K, Biswalo P, Talle A, Young People at Risk: Fighting AIDS in Northern Tanzania. Oslo, Norway: Scandinavian University Press; 1995:31–48 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohmer L, Kirumira E. Access to Reproductive Health Services: Participatory Research With Adolescents for Control of STDs. Los Angeles, CA: Pacific Institute for Women's Health; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vos T. Attitudes towards sex and sexual behavior in rural Matabele-land, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 1994;6:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glynn JR, Carael M, Auvert B, et al. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS 2001;15(suppl 4):S51–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaba B, Boerma JT, Pisani E, Baptise N. Estimation of levels and trends in age at first sex from African demographic surveys using survival analysis. [Google Scholar]