Abstract

Human matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are believed to contribute to tumor progression. Therapies based on inhibiting the catalytic domain of MMPs have been unsuccessful, but these studies raise the question of whether other MMP domains might be appropriate targets. The genetic dissection of domain function has been stymied in mouse because there are 24 related and partially redundant MMP genes in the mouse genome. Here, we present a genetic dissection of the functions of the hemopexin and catalytic domains of a canonical MMP in Drosophila melanogaster, an organism with only 2 MMPs that function nonredundantly. We compare the phenotypes of Mmp1 null alleles with alleles that have specific hemopexin domain lesions, and we also examine phenotypes of dominant-negative mutants. We find that, although the catalytic domain appears to be required for all MMP functions including extracellular matrix remodeling of the tracheal system, the hemopexin domain is required specifically for tissue invasion events later in metamorphosis but not for tracheal remodeling. Thus, we find that this MMP hemopexin domain has an apparent specialization for tissue invasion events, a finding with potential implications for inhibitor therapies.

Keywords: cancer, genetics, tissue remodeling

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of enzymes required for tissue remodeling, and their expression is up-regulated in tumors and inflamed tissue. As proteases that cleave extracellular matrix, MMPs have the potential to break down tissues, remove physical barriers, and liberate signaling molecules. All of these processes occur during tissue remodeling and during tumor progression. MMP mutant phenotypes in mice and flies demonstrate that MMPs are required for tissue remodeling (reviewed in ref. 1), and many lines of evidence implicate MMPs in promoting tumor progression including clinical data, mouse tumor studies, cell culture studies, and substrate analysis (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). Thus, MMPs are considered potential pharmaceutical targets for cancer therapies, although some MMPs may be important for inhibiting tumor progression (reviewed in ref. 3).

In the 1990s, the pharmaceutical industry performed clinical trials to test several MMP inhibitors that had been effective in preventing tumor progression in mouse (4–7). These compounds were designed to inhibit MMP catalysis at the active site (8). Unfortunately, in patients MMP inhibitors caused musculoskeletal pain and inflammation, which decreased the tolerated dose possibly below effective levels (9). From these studies, it can be concluded that the broad-spectrum inhibition of MMP catalysis is not a workable strategy for patient therapies as MMP catalysis is required in normal physiology. Other domains may be more appropriate inhibitor targets, and this possibility raises a question about MMP structure/function: Do the domains participate equally in different biological processes, or do some domains participate in some processes and not others?

MMPs contain 3 highly conserved domains: the pro, catalytic, and hemopexin domains (see Fig. 1). The catalytic domain mediates proteolysis of substrates and is often expressed in isolation for in vitro proteolysis assays. Endogenous MMP protein inhibitors called TIMPs (tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases) can reversibly occupy the active site of the catalytic domain and thus regulate its activity (10). The pro domain acts as a negative regulator of catalytic activity by occupying the active site; it is removed for enzyme activation. The hemopexin domain, which is connected to the catalytic domain by a flexible hinge, is a beta-propeller structure comprised of 4 repeating loops, each of which is homologous to the blood protein hemopexin. This domain is believed to mediate protein–protein interactions and to contribute to substrate specificity (11–15).

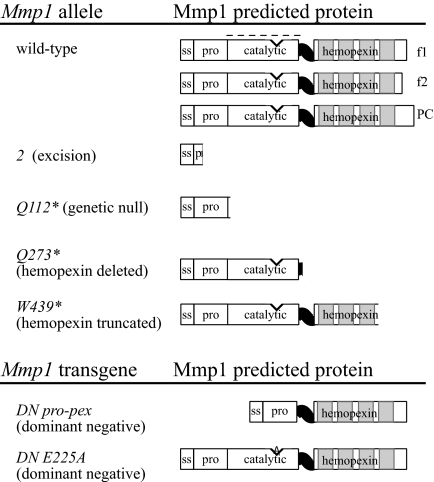

Fig. 1.

Predicted protein products of Mmp1 alleles and transgenes. (Upper) Predicted products from alleles at the Mmp1 genomic locus. The wild-type protein has the typical domain structure of a secreted MMP, including a signal sequence (ss), an inhibitory pro domain (pro), a catalytic domain (cat) (the catalytic core is shown as a v-shaped indentation), a flexible hinge domain (shown as a black wavy line), and a hemopexin domain (pex) containing 4 hemopexin loops (each light gray). We have identified cDNAs for 2 splice forms of Mmp1 as shown, form 1 (f1, known as PD in Flybase) and form 2 (f2). Flybase predicts an additional splice form PC, shown for completeness. The dashed line over the catalytic domain denotes the recombinant fragment used for generating anti-catalytic monoclonal antibodies. Allele 2, generated by P-element excision (18), deletes most of the coding sequence. Q112*, Q273*, and W439*, all recovered in an EMS mutagenesis screen (18), each contain a nonsense mutation causing premature termination as shown. (Lower) Mmp1 transgenes with dominant-negative activity, used under UAS transcriptional control. DN Pro-pex is a deletion construct lacking the entire catalytic domain. DN E225A is a point mutant that ablates the conserved E225 at the catalytic core, rendering the catalytic domain nonfunctional.

One method of assessing the functions of different domains is through genetic analysis of mutants. However, a complication of MMP genetic analysis in mouse models is that there are 24 MMP genes that exhibit partial redundancy (reviewed in ref. 1). In contrast, the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster has only 2 MMP genes, Mmp1 and Mmp2, and each has the conserved domain structure typical of mammalian MMPs (16–18). Each Drosophila MMP is required for viability, participating in different aspects of postembryonic tissue remodeling. Mmp1 is required for larval tracheal elongation and for tissue invasion during disc eversion during metamorphosis (18, 19); Mmp2 is required for histolysis and epithelial fusion during metamorphosis, and it is not required in the larval tracheal system (18). Interestingly, both Drosophila MMPs have been demonstrated by 3 groups to be required for tumor invasion using 2 different Drosophila tumor models (19–22), suggesting a conservation of pathological and physiological MMP function in Drosophila and humans. Here, we analyze the phenotypes of Mmp1 mutants disrupted for the hemopexin domain and compare them to Mmp1 null mutants. We find that the Drosophila Mmp1 catalytic domain is required for tracheal tissue remodeling whereas the hemopexin domain is not required for tracheal tissue remodeling, but rather is required specifically for tissue invasion events.

Results

In ref. 18, we reported that Mmp1 null mutant larvae failed to remodel their tracheae, the branched respiratory organ. This conclusion is based on the analysis of the two null alleles shown in Fig. 1: Mmp12 is a P-element excision allele lacking nearly all of the Mmp1 ORF; Mmp1Q112* is an EMS-induced mutation coding for a protein prematurely truncated in the catalytic domain (18). In null mutant animals (both homozygotes and transheterozygotes), the tracheal tubes appear to form normally during embryogenesis, but the tubes cannot elongate as the animal grows during larval instars. Instead, the mutant tracheal tubes are pulled tighter along the length of the animal, appearing increasingly taut until they frequently rip, with breaks appearing in the tubes (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Null alleles are homozygous lethal, and mutants die as second and third instar larvae (18). The null phenotype demonstrates that Mmp1 is required for tracheal elongation.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of catalytic and hemopexin-disrupted Mmp1 mutants

| Genotype | Nature of allele | Broken dorsal trunks, % (n*) | Survive to pupariation, % (n†) | Disc eversion lethal phenotypes (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | Control | 0 (100) | 100% (100) | All viable, wings and head everted (100) |

| Mmp1Q273*/CyO | Control | 2.5% (119) | ND | ND |

| Mmp12 | Null | 45% (105) | 0 (65) | NA |

| Mmp1Q112* | Null | 43% (54) | 0 (46) | NA |

| Mmp1Q112*/2 | Null trans-het | 44% (63) | ND | NA |

| Mmp1Q273* | Hemopexin deletion | 6.1% (147) | 59% (206) | 15/25 wings and head everted |

| 10/25 wings everted, no head | ||||

| Mmp1W439* | Hemopexin truncation | 7.0% (100) | 23% (100) | All have no wings or head everted (14) |

| Mmp1Q273*/W439* | Hemopexin trans-het | 6.1% (115) | 78% (115) | 21/24 wings and head everted |

| 4/24 wings everted, no head | ||||

| Mmp2W307*/Df | Mmp2 null trans-het | 0 (107) | 94% (107) | 11/25 wings and head everted |

| 14/25 wings everted, no head | ||||

| tubP > DN Pro-pex.f1 (1) | Ubiquitous hemopexin-interfering | 0.6% (163) | 96% (70) | 4/25 wings and head everted |

| 9/25 wings everted, no head | ||||

| 12/25 no wings or head everted | ||||

| tubP > DN Pro-pex.f1 (9) | Ubiquitous hemopexin-interfering | 0 (73) | 97% (73) | 10/26 wings and head everted |

| 16/26 no wings or head everted | ||||

| tubP > DN Pro-pex.f1 (1), DN Pro-pex.f1 (9) | 2 copies ubiquitous hemopexin- interfering | 2.7% (108) | 96% (98) | 22/25 wings everted, no head‡ |

| 3/25 no wings or head everted | ||||

| Mmp1Q273*/W439*; tubP > DN Pro-pex.f1 (1) | Hemopexin trans-het expressing hemopexin interfering | 1.8% (57) | ND | 5/25 wings and head everted |

| 1/25 one wing and head everted | ||||

| 14/25 wings everted, no head | ||||

| 5/25 one wing everted, no head | ||||

| tubP > DN E225A.f1 | Ubiquitous dominant negative | 0.9% (110) | 88% (110) | 1/25 wings and head everted |

| 24/25 wings everted, no head | ||||

| tubP > DN E225A.f2 | Ubiquitous dominant negative | 1.0% (96) | 85% (96) | All have wings everted, no head (26) |

| Mmp1Q273*/W439*; tubP > DN E225A.f1 | Hemopexin trans-het expressing dominant negative | 14.9% (47) | ND | 6/26 wings everted, no head |

| 20/26 no wings or head everted | ||||

| Btl > DN Pro-pex.f1 (9) | Hemopexin-interfering in tracheae | 0 (113) | ND | ND |

| Btl > DN E225A.f1 | Dominant negative in tracheae | 0.9% (107) | ND | ND |

| Btl > DN E225A.f2 | Dominant negative in tracheae | 0 (106) | ND | ND |

| Btl > Timp | Catalytic inhibition in tracheae | 61% (110) | 63% (100) | ND |

n, number of animals examined; ND, not done; NA, not applicable.

*Observed in 3rd instar larvae.

†First instar survival to pupariation was measured.

‡These animals were overall considerably less developed compared with each single insertion of DN Pro-pex.

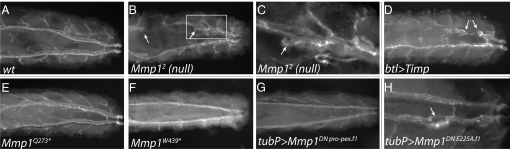

Fig. 2.

Tracheal phenotypes in larvae with nonfunctional Mmp1 catalytic and hemopexin domains. Reflected light images of the posterior ends of third instar larvae are shown, all in dorsal view with anterior on the left. (A) Wild-type. (B) Mmp12 null, displaying broken dorsal trunks (arrows show breaks). (C) Enlargement of box shown in B, with the broken dorsal trunk tip marked with an arrow. (D) Larva expressing the MMP catalytic inhibitor Timp in the tracheae using the btl-GAL4 driver, displaying broken dorsal trunks (arrows show breaks). (E) Mmp1Q273* larva, lacking the Mmp1 hemopexin domain, with apparently normal dorsal trunks. (F) Mmp1W439* larva, lacking part of the Mmp1 hemopexin domain, also displaying relatively normal dorsal trunks. (G) Larva ubiquitously expressing a hemopexin-interfering Mmp1 transgene, Mmp1DN Pro-pex.f1, with the tubP-GAL4 driver; these larvae also have normal dorsal trunks. (H) Larva expressing a hemopexin-interfering Mmp1 transgene, Mmp1DN E225A.f1, ubiquitously with the tubP-GAL4 driver; this panel is presented at higher magnification to show that each trunk has 1 or 2 pinched regions (arrow).

In an EMS screen to identify new alleles of Drosophila Mmp1, we identified alleles that specifically affect the hemopexin domain (18). The first allele, Q273*, has a nonsense mutation at Q273, leading to a premature truncation of the protein in the flexible hinge domain so that the predicted protein lacks the entire hemopexin domain (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the Q273* predicted protein mimics mammalian recombinant MMPs that lack a hemopexin domain, engineered to assay proteolysis in vitro. The second allele, W439*, has a nonsense mutation at W439, which causes a premature truncation of the hemopexin domain in the third of the 4 hemopexin loops (Fig. 1). These mutant alleles afford the opportunity to dissect the function of the hemopexin domain in vivo.

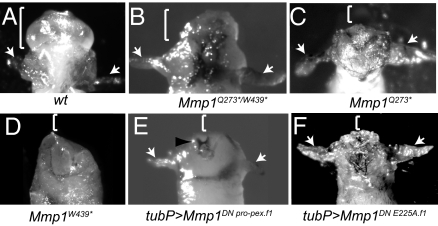

Tracheal breaks were infrequent in the Q273* and W439* homozygous larvae (see Table 1). Instead, these hemopexin mutants displayed fairly normal tracheae, which were able to grow as the animal elongated (Fig. 2). This observation was surprising, because we expected that hemopexin-mediated substrate recognition would be required for all Mmp1-mediated functions, including tracheal elongation. Although we did observe slightly elevated levels of tracheal breaks (in ≈7% of animals, Table 1), these were much lower than levels in null animals (≈45%), and we did not observe the taut stretched dorsal trunks typical of the null animals. It is likely that the tracheal breaks in the hemopexin mutant larvae are caused by the overall reduction in Mmp1 protein (see below) rather than by the lack of the hemopexin domain. Animals mutant for either hemopexin allele Q273* or W439* frequently survived to metamorphosis, when they died with body malformations associated with a failure of disc eversion (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Transheterozygotes of the genotype Q273*/W439* also had normal larval dorsal trunks with infrequent breaks, survived to pupariation, and sometimes failed to evert imaginal discs during metamorphosis. Early in disc eversion, imaginal disc peripodial and stalk cells traverse 2 layers of basement membrane to invade the larval body wall (23). Srivastava et al. have demonstrated that in animals compromised for Mmp1 function, the normal invasion of basement membranes by disc epithelia fails, leading to failures of disc eversion (19). The observation that both Mmp1 hemopexin mutants fail to evert discs indicates that the hemopexin domain is required selectively for developmental tissue invasion but not for remodeling the tracheal tubes (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Disc eversion phenotypes in pupae lacking functional Mmp1-hemopexin domains. Reflected light images of the anterior regions of pupae removed from their pupal cases are shown. (A) Wild-type at approximately stage P5 with everted head (bracket) and wings (arrows); wings evert within 6 h after puparium formation (here they were pulled away from the body for better visualization) and the head everts ≈12 h after puparium formation. (B–F) Mmp1 mutants that have been allowed to develop several days after puparium formation. (B) Mmp1Q273*/W439* transheterozygote with everted head and wings, not able to complete development. (C) Mmp1Q273* with everted wings (arrows), but it has not everted its head and so appears headless (bracket). (D) Mmp1W439* that has not everted its head (bracket) or wings. (E) Pupa expressing Mmp1DN Pro-pex.f1 ubiquitously with tubP-GAL4, with wing eversion (arrows) but no head eversion (bracket); black arrowhead shows the larval mouth hooks, still attached to the body. (F) Pupa expressing Mmp1DN E225A.f1 ubiquitously with tubP-GAL4, that has everted wings (arrows) but not head (bracket). This genotype mimics the cryptocephalic phenotype of Mmp1Q273* but with higher penetrance.

To understand these alleles better, we examined Mmp1 wild-type and mutant protein mobility and expression levels by Western blot analysis with anti-Mmp1-catalytic-domain monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 4; comparisons of the individual monoclonal antibodies are shown in supporting information (SI) Fig. S1). Lysates of wild-type embryos and larvae showed several Mmp1-specific bands, most prominently at 64, 52, and 46 kDa, with a larger band at 74 kDa observed prominently in embryos but only faintly in larvae. No bands were observed in a control extract made from Mmp1 null embryos and larvae, confirming the identity of the bands as Mmp1. The expected size of Mmp1 is unclear because of different splice isoforms: We previously identified cDNAs for 2 alternatively spliced proteins we called Mmp1.f1 (aka Mmp1-PD at Flybase, FBpp0271772) and Mmp1.f2 (18); another isoform called Mmp1-PC is reported at Flybase FBpp0271771. No functional differences are known for the splice forms. All of these isoforms contain the full catalytic and hemopexin domains and differ only in their carboxy-terminal ends (see Fig. 1); these are predicted to encode proteins of 65 (PC), 59 (f1 or PD), and 57 (f2) kDa. Additionally, any expressed Mmp1 isoform is expected to be activated by removal of the 108-aa autoinhibitory Pro domain, resulting in products reduced in size by ≈11.6 kDa. Thus, the 74 kDa band in embryos is substantially larger than expected, perhaps owing to posttranslational modification.

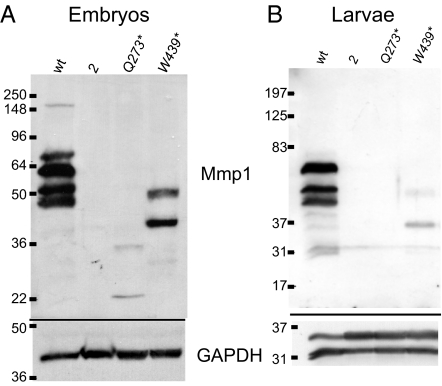

Fig. 4.

Western blots of Mmp1 mutants. (A) Each lane contains lysate equivalent to 50 embryos of the following genotypes: w1118 wild type, null Mmp12 (control for antibody specificity), the hemopexin-deleted mutant Mmp1Q273*, and the hemopexin-truncated mutant Mmp1W439*. (Lower) shows GAPDH loading control. (B) Each lane contains lysate of second instar larvae of the following genotypes: w1118 wild type, null Mmp12 (control for antibody specificity), the hemopexin-deleted mutant Mmp1Q273*, and the hemopexin-truncated mutant Mmp1W439*. The equivalent of 12 animals were loaded in all lanes except for Mmp12 with 18, because their small size required more animals to achieve equivalent loading. The highest molecular-weight band of Mmp1, likely representing the uncleaved zymogen, is barely apparent in larvae in contrast to in embryos. (Lower) Loading control of GAPDH, which apparently is expressed differently in embryos and larvae.

We observed protein bands for both hemopexin mutants. Mmp1Q273* protein is predicted to be 30 kDa (as the nonsense mutation affects all splice forms). In embryo lysates, 2 faint bands were observed at 35 kDa and 22 kDa, indicating possible posttranslational modification. The low level of Mmp1Q273* protein was consistent with our previous genetic analysis, which showed that Q273* is a hypomorphic allele whose severity increases when in trans to a null allele (18). Thus, the Q273* allele can be classified as a hypomorph with respect to the catalytic domain, and as a null with respect to the hemopexin domain, because this domain is absent from the gene product. Despite several attempts, the level of mutant protein in second instar larvae was below our detection threshold, although phenotypic analysis indicates that some protein is present in Q273* larvae. It is remarkable that tracheal elongation, a process that requires Mmp1, can still occur with these undetectably low levels of Mmp1 protein in second instar larvae. Most importantly, the Q273* allele demonstrates that the hemopexin domain is dispensable for tracheal elongation.

For the W439* mutant protein, the zymogen is expected to be 49 kDa, and 2 distinct bands were observed at 50 and 38 kDa with a fainter band at 31 kDa (Fig. 4B), indicating that this mutant protein is the expected size within error of our observation. We have established that the W439* allele is a hypomorph, because more animals pupariate in homozygotes than in W439*/2 animals; but W439* is a stronger allele than Q273*, as shown by its earlier lethality (both in homozygotes and in trans to allele 2) (18). We were surprised that so much more protein was evident for W439* than for the weaker Q273* mutant, suggesting that although W439* mutant message is translated, most of the protein is not functional—perhaps it does not fold correctly, is not exported from the cell, and therefore would not be not posttranslationally modified. For both alleles then, the reduction in protein levels, or specifically in catalytic domain levels, may explain the partial larval lethality and the infrequent tracheal breaks observed in the two hemopexin mutants.

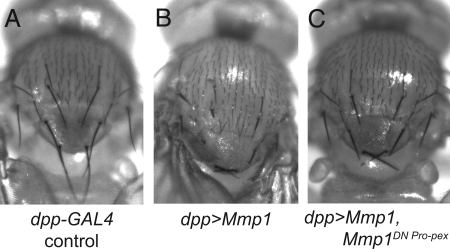

We wanted to independently assess whether the hemopexin domain participates in larval tracheal remodeling, without the complications of reduced catalytic domain levels in these hemopexin mutants. To disrupt the hemopexin-domain function, we constructed a hemopexin-interfering Mmp1 transgene. This mutant, DN Pro-pex, removed the entire catalytic domain coding region but retained a full-length hemopexin domain (Fig. 1). It was predicted to behave as a dominant negative by interfering with wild-type Mmp1 in binding protein partners via the hemopexin domain. Its dominant-negative nature was experimentally confirmed. We showed that the misexpression of Mmp1 with a dpp-GAL4 driver led to a phenotype of short, thick, and easily broken thoracic bristles, and that this bristle phenotype was suppressed by the coexpression of UAS-Timp (18). DN Pro-pex was also able to suppress thoracic bristle phenotypes caused by dpp-GAL4 driving Mmp1 expression in adult flies (Fig. 5). This suppression was not caused by the dilution of GAL4 spread between 2 UAS elements, because the presence of UAS-GFP had no effect on the dpp>Mmp1 bristle phenotype (Fig. 5B). Because it phenocopied the endogenous Mmp1 inhibitor Timp, we conclude that Mmp1DN Pro-pex acts in a dominant-negative fashion.

Fig. 5.

Mmp1DN Pro-pex dominantly suppresses an Mmp1 overexpression phenotype. (A) Bristles on the thorax of a control fly appear long and tapered. Genotype: dpp-GAL4. (B) When Mmp1 is overexpressed, the bristles become short, stubby and easily broken. Genotype: dpp-GAL4, UAS-Mmp1.f1, UAS-GFP. (C) When Mmp1DN Pro-pex.f1 is coexpressed with Mmp1, the bristle phenotype is significantly suppressed. Genotype: dpp-GAL4, UAS-Mmp1.f1, UAS-Mmp1DN Pro-pex.f1.

When induced in the tracheal system specifically with btl-GAL4 or throughout larvae ubiquitously with tubP-GAL4, DN Pro-pex did not induce the taut tracheae and dorsal trunk breaks seen in the Mmp1 catalytic loss-of-function mutants (Table 1); indeed these larvae appeared indistinguishable from wild-type (Fig. 2) and nearly all survived to pupariation, indicating that the hemopexin domain of the dominant-negative protein does not interfere with larval Mmp1 functions in the tracheae. During metamorphosis, however, the ubiquitous expression of DN Pro-pex was lethal. These mutants arrested development with disc eversion defects, phenocopying the Q273* mutants (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Because the Q273* mutant discs are unable to invade basement membrane during disc eversion (19), the similar phenotypes of the DN Pro-pex mutants strongly suggest that the ubiquitously expressed hemopexin domain interferes with the function of Mmp1 in basement membrane tissue invasion. As with the Mmp1 hemopexin-deficient mutants, the disc eversion phenotypes were strong but variable (Table 1). Ubiquitous overexpression phenotypes were examined in 2 lines carrying independent insertions of DN Pro-pex and in a recombinant line containing both insertions; all caused widespread pupal lethality and disc eversion failures, and yet none interfered with larval development (Table 1). From the analysis of this dominant negative, and the hemopexin mutants, we conclude that the hemopexin domain does not participate in larval tracheal remodeling, whereas the hemopexin domain is required for Mmp1 function during disc eversion. The Mmp1 hemopexin domain of Drosophila is specifically required during some functions but not others.

We tested another Mmp1 dominant-negative construct, DN E225A, which contains full-length catalytically dead Mmp1 with a conserved active-site glutamic acid residue replaced with an alanine residue. The dominant-negative nature of this allele has been demonstrated in the embryonic nervous system and in cell culture (24, 25). This mutant had the potential to interfere with both the hemopexin and the catalytic domain. Interestingly, when expressed ubiquitously throughout the animal, larvae were able to develop without tracheal breaks and survive to pupariation; however, close examination of the larval tracheae revealed small areas that appeared pinched (Fig. 2), suggesting that this dominant-negative may interfere with the wild-type Mmp1 catalytic function. When expressed ubiquitously, the phenotype of the DN E225A mutant was dramatic during metamorphosis: Pupae developed into cryptocephalic flies, with well-developed bodies and wings, but without head eversion so that they appeared headless. This phenotype was much less variable than the Mmp1 hemopexin allele phenotypes or the DN Pro-pex phenotype.

To compare the nature of the 2 dominant-negative mutants, we expressed each transgene in an Mmp1 mutant background. We chose the Q273*/W439* background because stronger Mmp1 alleles caused larval death even without dominant-negative Mmp1 expression. We reasoned that, if DN Pro-pex protein is out-competing Mmp1 for protein partners that bind to the hemopexin domain, then the Q273*/W439* phenotype should be mostly unchanged in the presence of DN Pro-pex, because this hemopexin-mutant Mmp1 never could bind to those protein partners. Conversely, if DN E225A is competing with wild-type Mmp1 for protein partners that bind both its hemopexin domain and its catalytic domain, then the Q273*/W439* phenotype should be greatly enhanced by the expression of DN E225A, because the dominant-negative will interfere with the catalytic function of the hemopexin-truncated proteins. As predicted, the ubiquitous expression of DN E225A in the Q273*/W439* background caused severe defects in disc eversion, with most animals unable to evert either wings or head and stalling very early in metamorphosis (Table 1); this is a stronger phenotype than is observed in either Q273*/W439* or tub>DN E225A alone. As larvae, they also had increased tracheal breaks and appeared sluggish. In contrast, the range of disc eversion phenotypes observed from DN Pro-pex overexpression in the hemopexin-mutant background were similar to the Q273*/W439* background (see Table 1), although the penetrance of head eversion failure was higher in the presence of DN Pro-pex. As larvae, these animals were still able to elongate their tracheae without breaks. We interpret these results to mean that the DN E225A mutant protein can interfere with the Mmp1 catalytic domain whereas DN Pro-pex interferes with Mmp1 via the hemopexin domain.

From the null phenotype, it is clear that Mmp1 is required for tracheal remodeling during larval growth. To confirm the requirement for Mmp1 catalytic activity, rather than some unexpected function, we misexpressed the endogenous MMP inhibitor Drosophila Timp. TIMPs inhibit the catalytic activity of MMPs with a 1:1 stoichiometry by occupying the active site (10), and fly Timp has been shown to inhibit Mmp1 both in vitro and in vivo (18, 26). [Fly Timp can also inhibit Mmp2 (18, 26), but there is no evidence that Mmp2 is required in the larval tracheal system (see Table 1).] Larvae expressing Timp throughout the tracheal system with btl-GAL4 displayed tightly stretched tracheal tubes that developed breaks in their dorsal trunks at similar frequencies to those of Mmp1 null mutants (Table 1 and Fig. 2), confirming that the catalytic function of Mmp1 is required for normal elongation of the tracheal system during larval growth.

Thus, in Drosophila the Mmp1 catalytic domain is required during both larval tracheal elongation and during metamorphic tissue invasion. In contrast, the hemopexin domain is not required for tracheal elongation but is required during the Mmp1-mediated processes of tissue invasion during metamorphosis.

Discussion

We used the genetic strengths of Drosophila to examine the function of an MMP hemopexin domain. We have defined the requirement for the hemopexin domain during metamorphosis by examining the phenotypes of Mmp1 hemopexin-disrupted alleles Q273* and W439* and Mmp1 transgenes DN Pro-pex and DN E225A. All of these mutant animals can remodel their tracheal tubes during larval growth but have severe defects in metamorphosis consistent with failures in tissue invasion of basement membrane. Three independent genetic experiments show that the catalytic domain is required for tracheal elongation in larvae: the phenotype of Mmp12 null (P-excision) homozygotes, the phenotype of Mmp1Q112* null (EMS-generated) homozygotes, and the phenotype of animals misexpressing the MMP catalytic inhibitor Timp. Animals with any of these genetic constitutions display stretched and broken tracheal tubes, indicating that Mmp1-mediated proteolysis is required for normal tracheal remodeling. Inhibition of Mmp1 catalysis during metamorphosis also causes disc eversion phenotypes, demonstrating that the catalytic domain is required for both tracheal elongation and disc eversion (19).

Four different genetic approaches to disrupting the hemopexin domain function all show defects in pupal disc eversion, but the observed phenotypes are not uniform. Q273* homozygotes, which lack the Mmp1 hemopexin domain entirely, have phenotypes ranging from no eversion defects to severe defects, as do animals expressing the hemopexin-interfering DN Pro-pex mutant. This phenotypic variability is also apparent in Mmp12 null mutants whose larval defects have been partially suppressed by a mutation in Tubby (manuscript in preparation). This variability strongly suggests that there is partial genetic redundancy in disc eversion between Mmp1 and another gene. However, the DN E225A phenotype is much tighter, with pupae everting wings but failing to evert heads. This more uniform phenotype suggests that DN E225A interferes with both Mmp1 and its partially redundant partner. Although the identity of the partially redundant partner is unknown, a good candidate is Mmp2 because of its homology to Mmp1, because of the Mmp2 head eversion phenotypes, and because DN E225A has been shown to interfere with both Mmp1 and Mmp2 in the embryonic nervous system (24).

Our data indicate that the Drosophila Mmp1 hemopexin domain participates selectively in some biological processes but not others. How can this unexpected result be explained? It seems likely that the hemopexin domain is a protein–protein interaction domain, as previously thought, but that it only binds to a subset of Mmp1's binding partners and substrates; others bind directly to the catalytic domain. These hemopexin binding partners could be substrates, localization determinants, or have other functions. It is reasonable to assume that Mmp1 substrates in tracheal elongation and in disc eversion are different, because the tracheae are lined with a chitinous apical extracellular matrix that must be remodeled during elongation, whereas imaginal disc eversion requires remodeling of a basement membrane containing collagen IV and laminin (19, 27). Importantly, in addition to its role in developmental tissue invasion, Mmp1 is required in Drosophila for the local invasion of both transplanted and clonally induced tumors (19–21). These tissue invasion events require the hemopexin domain, because it has been shown that tumors induced in Q273* homozygous mutants have reduced invasive capacity; thus the hemopexin domain mediates both developmental and pathological tissue invasion (19).

Our data demonstrate that the domains of Drosophila Mmp1 do not contribute equally to the different developmental functions for Mmp1. Rather, the hemopexin domain is dispensable for normal tracheal remodeling, whereas it is required for tissue invasion later at metamorphosis. These findings raise the possibility that a human MMP hemopexin domain may be a candidate target for chemotherapies in patients. Thus, specificity of MMP inhibition could be achieved by targeting a subset of its functions.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Genetics.

Drosophila melanogaster stocks used for this study are listed in SI Materials. Mmp1 stocks were maintained over CyO, arm-GFP balancers, and homozygous mutants were selected as late embryos or first instar larvae lacking GFP fluorescence. Larvae were maintained on yeasted agar plates until third instar, transferring them onto fresh plates every 1–2 days. Tracheal observations were made in live animals or heat-killed (by placing larvae on a coverslip and placing it on a 95°C block a few seconds until they stopped moving).

Construction of Dominant-Negative Mmp1.

For DN Pro-pex, mutagenic PCR was used to delete the region coding for the catalytic and hinge domains in both splice forms Mmp1.f1 and Mmp1.f2 in pBluescript. The protein products of the resulting mutants were missing amino acids 112–298. The mutant ORF was sequenced, ligated into pUAST and injected into Drosophila embryos. Similar phenotypes were observed for the overexpression of DN Pro-pex.f1 and DN Pro-pex.f2. DN E225A.f2 was made according to (25), using the cDNA for Mmp1 form 2.

Western Blot Analysis.

Sixty embryos 17–20 h AEL were homogenized in 36 μL of 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer (LSB). A total of 30 μL of lysate, equivalent to 50 embryos, were loaded per lane. Twenty to fifty 2nd-instar larvae were homogenized in 50 μL of 2× LSB, and 12 larvae equivalents were loaded into each lane (18 for Mmp12 because of their small size). Proteins were transferred to Hybond-C Extra (Amersham). Anti-Mmp1 monoclonals 3B8, 3A6, 5H7 were used as 1:1:1 mixture diluted 1:10. These antibodies were all raised against the catalytic domain of Mmp1 (18) and are available at the DSHB. Primary antibody incubation was overnight at 4 °C, and secondary antibodies (HRP-labeled goat-anti-mouse; Jackson) were diluted 1:5,000 and incubated for 1 h at RT. Loading was confirmed by goat anti-GAPDH (Imgenex) used at 1:5,000 for 2h at RT; followed by HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat (Jackson) used at 1:10,000 for 1h at RT. Bands were detected using the Amersham ECL kit and film.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Gina Dailey for plasmid construction and Heather Broihier, Laura Lee, and Patrick Page-McCaw for comments on the manuscript. The monoclonals used for this study are available at the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM073883 and by a Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar's Award from the March of Dimes.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804171106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goss KJ, Brown PD, Matrisian LM. Differing effects of endogenous and synthetic inhibitors of metalloproteinases on intestinal tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:629–635. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981123)78:5<629::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergers G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergers G, Javaherian K, Lo KM, Folkman J, Hanahan D. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on multistage carcinogenesis in mice. Science. 1999;284:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: Trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittaker M, Floyd CD, Brown P, Gearing AJ. Design and therapeutic application of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2735–2776. doi: 10.1021/cr9804543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fingleton B. MMPs as therapeutic targets—still a viable option? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomis-Ruth FX, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of the human matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 by TIMP-1. Nature. 1997;389:77–81. doi: 10.1038/37995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson ML, Atkinson SJ, Knauper V, Murphy G. Specific collagenolysis by gelatinase A, MMP-2, is determined by the hemopexin domain and not the fibronectin-like domain. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:158–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gioia M, et al. Modulation of the catalytic activity of neutrophil collagenase MMP-8 on bovine collagen I. Role of the activation cleavage and of the hemopexin-like domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23123–23130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knauper V, et al. The role of the C-terminal domain of human collagenase-3 (MMP-13) in the activation of procollagenase-3, substrate specificity, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase interaction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7608–7616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung L, et al. Identification of the (183)RWTNNFREY(191) region as a critical segment of matrix metalloproteinase 1 for the expression of collagenolytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29610–29617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozanov DV, et al. The hemopexin-like C-terminal domain of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase regulates proteolysis of a multifunctional protein, gC1qR. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9318–9325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llano E, et al. Structural and Enzymatic Characterization of Drosophila Dm2-MMP, a Membrane-bound Matrix Metalloproteinase with Tissue-specific Expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23321–23329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llano E, Pendas AM, Aza-Blanc P, Kornberg TB, Lopez-Otin C. Dm1-MMP, a matrix metalloproteinase from Drosophila with a potential role in extracellular matrix remodeling during neural development. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35978–35985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page-McCaw A, Serano J, Sante JM, Rubin GM. Drosophila matrix metalloproteinases are required for tissue remodeling, but not embryonic development. Dev Cell. 2003;4:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava A, Pastor-Pareja JC, Igaki T, Pagliarini R, Xu T. Basement membrane remodeling is essential for Drosophila disc eversion and tumor invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2721–2726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611666104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaucher M, Hersperger E, Page-McCaw A, Shearn A. Metastatic ability of Drosophila tumors depends on MMP activity. Dev Biol. 2007;303:625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhlirova M, Bohmann D. JNK- and Fos-regulated Mmp1 expression cooperates with Ras to induce invasive tumors in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2006;25:5294–5304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page-McCaw A. Remodeling the model organism: Matrix metalloproteinase functions in invertebrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastor-Pareja JC, Grawe F, Martin-Blanco E, Garcia-Bellido A. Invasive cell behavior during Drosophila imaginal disc eversion is mediated by the JNK signaling cascade. Dev Cell. 2004;7:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller CM, Page-McCaw A, Broihier HT. Matrix metalloproteinases promote motor axon fasciculation in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2008;135:95–109. doi: 10.1242/dev.011072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang S, et al. An MMP liberates the Ninjurin A ectodomain to signal a loss of cell adhesion. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1899–1910. doi: 10.1101/gad.1426906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei S, Xie Z, Filenova E, Brew K. Drosophila TIMP is a potent inhibitor of MMPs and TACE: Similarities in structure and function to TIMP-3. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12200–12207. doi: 10.1021/bi035358x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbott LA, Natzle JE. Epithelial polarity and cell separation in the neoplastic l(1)dlg-1 mutant of Drosophila. Mech Dev. 1992;37:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90014-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.